Abstract

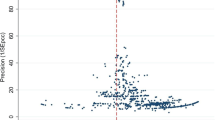

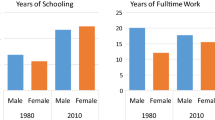

Despite several theoretical approaches linking rising market power to more income inequality, a theoretical-based empirical quantification of this relationship has not been made. We devised a directed technical change model and characterize this relationship. To test our model, we calculate concentration indexes and relate them with skill-premium using industry data per country for 40 countries from 1995 to 2011. In general, we show a negative and robust relationship between the market power index and wage inequality. Additional evidence shows that results tend to be different for countries with different income levels and for different initial values of skill-premium and market power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

see Remarks by the President in State of the Union Address (Jan. 25, 2015).

The si is the share of industry i on the output, that is, \(HHI={{\sum }_{i}^{n}} {s_{i}^{2}}\), where n is the number of industries in the economy.

To classify countries by income groups we use the GNI per capita calculated using the World Bank Atlas method and its respective thresholds.

We cannot exclude certain forms of reverse causality that could be potentially suggested by alternative theoretical relationships.

To compute the employment share we use the number of persons engaged and the population data from the PWT 9.0 and, to compute the country trade openness we use the imports and exports share also from the PWT 9.0.

A positive relationship between income inequality and openness was also obtained in Barro (2000).

Bucci et al. (2003) use the efficiency wages argument to explain the negative relationship between market concentration and wage inequality. In the research market there are monitoring problems that imply that the firms with lower markups have to set a higher efficiency wage, An alternative explanation may be the labor unions strength.

Introduction of the lagged value and first-differences help to prevent potential reverse causality to be a source of empirical endogeneity. Introduction of time and sector-country dummies helps to consider heterogeneity effects or idiosyncratic shocks by sector-country, time effects and of course, omitted variables.

For example, Duffy and Papagiourgiou (2000) present estimates for σ using a panel database for 82 countries over a 28-year period. Nonlinear estimations for σ oscillate between 1.2 and 2.3, while linear estimations oscillate around 1.4.

We thank a referee this interesting discussion.

References

Acemoglu D (2002) Directed technical change. Rev Econ Studies 69(4):781–809

Acs ZJ, Audretsch DB (1987) Innovation, market structure, and firm size. Rev Econ Stat 69(4):567–574

Aghion P, Bloom N, Blundell R, Griffith R, Howitt P (2005) Competition and innovation: an Inverted-U relationship. Q J Econ 120(2):701–728

Antonelli C, Gehringer A (2017) Technological change, rent and income inequalities: A Schumpeterian approach. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 115:85–98

Asteriou D, Dimelis S, Moudatsou A (2014) Globalization and income inequality: a panel data econometric approach for the EU27 countries. Econ Model 36:592–599

Barro RJ (2000) Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. J Econ Growth 5(1):5–32

Bergh A, Nilsson T (2010) Do liberalization and globalization increase income inequality? Eur J Polit Econ 26:488–505

Birchenall JA (2001) Income distribution, human capital and economic growth in Colombia. J Dev Econ 66(1):271–287

Blundell R, Griffith R, Van Reenen J (1999) Market share, market value and innovation in a panel of british manufacturing firms. Rev Econ Stud 66(3):529–554

Borjas G, Ramey V (1995) Foreign competition, market power and wage inequality. Q J Econ 110(4):1075–1110

Bucci A, Fiorillo F, Staffolani S (2003) Can Market Power influence Employment, Wage Inequality and Growth. Metroeconomica 54(2-3):129–160

Card D, Lemieux T (2001) Can falling supply explain the rising return to college for younger men? a cohort-based analysis. Q J Econ 116(2):705–746

Castiglione C, Infante D (2014) ICTS and time-span in technical efficiency gains. A stochastic frontier approach over a panel of Italian manufacturing firms. Econ Model 41(C):55–65

Comamor W, Smiley RH (1975) Monopoly and the distribution of wealth. Q J Econ 89(2):177–194

Creedy J, Dixon R (1999) The distributional effects of monopoly. Aust Econ Pap September:223–237

De Gregorio J, Lee J (2002) Education and income inequality: New evidence from Cross-Country data. Rev Income Wealth 48(3):395–416

Dietzenbacher E, Los B, Stehrer R, Timmer M, De Vries G (2013) The construction of world input–output tables in the WIOD project. Econ Syst Res 25(1):71–98

Ding S, Meriluoto L, Reed WR, Tao D, Wu H (2011) The impact of agricultural technology adoption on income inequality in rural China: Evidence from southern Yunnan Province. China Econ Rev 22(3):344–356

Dorn F, Fuest C, Potrafke N (2018) Globalisation and Income Inequality Revisited. CESifo Working Paper Series 6859, CESifo Group Munich

Dorn F, Schinke C (2018) Top income shares in OECD countries: The role of government ideology and globalization. World Econ 00:1–37

Duffy J, Papagiourgiou C (2000) A cross-country empirical investigation of the aggregate production function specification. J Econ Growth 5:87–120

Epifani P, Gancia G (2008) The skill bias of world trade. Econ J 118 (530):927–960

Fórster M., Thó I. (2015) Cross-Country Evidence of the multiple causes of inequality changes in the OECD area. Handbook of Income Distribution 2B, ch.19:1729–1843

Grossman G, Helpman E (1991) Innovation and growth in the global economy Massachusetts. MIT Press, Cambridge

Haskel J, Slaughter MJ (2001) Trade, technology and UK wage inequality. Econ J 111:163–187

Hornstein A, Krusell P, Violante GL (2005) The effects of technical change on labor market inequalities. Handbook of Econ Growth 1:1275–1370

Kuznets S (1955) Economic growth and income inequality. Am Econ Rev 45:1–28

Jaumotte F, Lall S, Papageorgiou C (2013) Rising Income Inequality: technology, or Trade and Financial Globalization?. IMF Economic Review 61 (2):271–309

Jerzmanowski M, Tamura R (2015) Directed technological change: a quantitative analysis. Clemson University working paper

Martins P, Pereira P (2004) Does education reduce wage inequality? quantile regression evidence from 16 countries. Labour Econ 11:355–371

Milanovic B (2000) Determinants of Cross-Country Income Inequality: An “Augmented” Kuznets hypothesis. Equality, Participation Transition. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Murphy K, Welch F (1992) The structure of wages. Q J Econ 107(1):285–326

Nolan E, Santos P, Shi G (2012) Market concentration and productivity in the United States corn sector: 2002-2009, 2012 Annual Meeting, August 12-14, 2012, Seattle, Washington 125941, Agricultural and Applied Economics Association

Roine J, Vlachos J, Waldenström D. (2009) The long-run determinants of inequality: What can we learn from top income data? J Public Econ 93:974–988

Rognlie M (2015) Deciphering the Fall and Rise in the Net Capital Share: Accumulation or Scarcity? Brook Pap Econ Act Spring:1–68

Rodriguez-Pose V, Tsellios V (2009) Education and income inequality in the regions of the european union. J Reg Sci 49(3):411–437

Rattsø J, Stokke H (2013) Regional Convergence of Income and Education: Investigation of Distribution Dynamics. Urban Studies, online before print. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013498625

Sequeira T, Santos M, Ferreira-Lopes A (2017) Income inequality, TFP and human capital. Econ Rec 93(300):89–111

Santos M, Sequeira T, Ferreira-Lopes A (2017) Income inequality and technological adoption. J Econ Issues 51(4):979–1000

Stiglitz J (2012) The price of inequality. W.W. Norton & Company, London

Teulings C, van-Rens T (2008) Education, growth, and income inequality. Rev Econ Stat 90(1):89–104

Wang L (2011) How does education affect the earnings distribution in urban china? Oxf Bull Econ Stat 75:435–454

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the useful suggestions and comments of the Editor and three anonymous referees which greatly contributed to improve the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Magalhães, M., Sequeira, T. & Afonso, Ó. Industry Concentration and Wage Inequality: a Directed Technical Change Approach. Open Econ Rev 30, 457–481 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-018-9513-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-018-9513-0