Abstract

In hearts, complex spatial–temporal patterns of action potential waves may cause life-threatening arrhythmia. Unlike the conventional defibrillation which uses high-voltage electric shocks associated with severe side effects, the new method of wave emission from heterogeneities (WEHs) merits close investigation. In our previous studies of the WEH to terminate arrhythmia in idealized conditions, we found that a circularly polarized electric field (CPEF) not only needs a lower voltage, but also has higher efficiency than a uniform electric field (UEF). But the effect of a CPEF on a real cardiac heterogeneity with irregular boundary shape remains unknown. Here, we consider elliptical heterogeneities whose boundary curvatures and orientations change in a similar way as irregular heterogeneities and study the effect of the changing boundary curvature and orientation on the WEH. We find that, unlike the UEF, the CPEF is not affected by the change of boundary curvature and orientation. Besides, the CPEF needs a lower voltage to induce wave emission from an elliptical heterogeneity than the UEF. Hence, it has advantages for the application of the WEH in clinical treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the incidence of sudden cardiac deaths increases. The most of them are led by arrhythmia [1]. Cardiac experiments show that arrhythmia, including tachycardia and fibrillation, have a close relation with the self-organization of spiral (or scroll) waves and their turbulence [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Thus, many researchers dedicate new methods to drive spirals away [9,10,11,12,13].

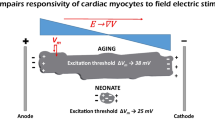

Clinically, the termination of fibrillation relies on high-voltage electric shocks which reset all electric activities in cardiac tissues. But a high voltage may harm the heart due to its severe side effects [14,15,16,17]. Recently, an approach called wave emission from heterogeneities (WEHs) gets more and more attention [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In particular, under the external electric field, the membrane potential near conductivity heterogeneities (anatomic or functional obstacles) can be distributed. The areas at both sides of a heterogeneity can be depolarized and hyperpolarized separately, which can be called as Weidman zones [25]. If the external electric strength exceeds a threshold, these conductivity heterogeneities can act as virtual electrodes [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Thereby, they can excite nearby cardiac tissues, emit action potential waves, and eventually synchronize the whole heart to terminate arrhythmia. Heart is a highly heterogeneous organ, full of conductivity heterogeneities. They can be blood vessels, scars (due to infarction), small-scale discontinuities, etc. [33]. Especially, blood vessels widely distribute in cardiac tissues. Observing a cardiac tissue slice, we can see most of blood vessels are in shapes of ellipses or circles. Although some of them are in irregular shapes, their boundary curvatures change in a similar way of ellipses.

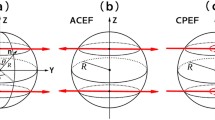

For the WEH, other works focused on applying the uniform electric field (UEF) pluses [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In our previous studies, we found that the WEH in response to a circularly polarized electric field (CPEF) also has shown its unique ability to terminate arrhythmia [34,35,36]. To be specific, a CPEF has a higher success rate and a larger vulnerable window to remove spiral waves that a UEF. The circular wave trains induced by a CPEF have a higher frequency than by a UEF and thus can more effectively suppress the spiral turbulence at a lower voltage. In order to develop and optimize such a low-voltage high-efficiency approach using a CPEF, it is essential to understand the mechanism of the wave emission induced by a CPEF from blood vessels, scars, etc. In this paper, we demonstrate effects of the changing boundary curvature and orientation of these realistic heterogeneities on the WEH by a CPEF and provide a deeply comprehensive understanding for the wave emission by a CPEF. Without loss of generality, we choose an elliptical shape of the heterogeneity to study the influence of its changing boundary curvature and orientation on the induction of the wave emission.

2 Model and methods

In this paper, our numerical analysis is based on the reaction–diffusion equations. We use the Luo–Rudy model [37] to describe ion channel currents through cardiomyocyte membrane. They can be expressed as follows:

where V is the membrane potential and \(I_\mathrm{ion} \) is the sum of ion channel currents which consist of a fast sodium current \(I_{Na} \), a slow inward current \(I_{si} \), a time-dependent potassium current \(I_K \), a time-independent potassium current \(I_{K1} \), a plateau potassium current \(I_{Kp} \), and a time-independent background current \(I_b \). The above currents are obtained by nonlinear ordinary differential equations defined in Ref. [38]. \(C_m \) is the membrane capacitance and is set to be \(1{\mu F}/{\hbox {cm}^{2}}\) in our research for simplicity. D is the diffusion coefficient and is set to be \(0.001{\hbox {cm}^{2}}/{\hbox {ms}}\). In a mono-domain model, the effect of an external electric field on a heterogeneity can be expressed as a Neumann boundary condition: \(\mathbf{n}\cdot ({\nabla V-\mathbf{E}})=0\), where \(\mathbf{n}\) is the normal vector to the boundary of the heterogeneity and E is the external electric field vector.

In our simulations, since the rotational symmetry of the elliptical heterogeneity, we exemplify a counterclockwise rotating CPEF. It can be expressed as \(\mathbf{E}=({E_x ,E_y })\), where \(E_x =E\cos ({\omega _{{\textit{CPEF}}} t})\) and \(E_y =E\cos ({\omega _{{\textit{CPEF}}} t+3\pi /2})\). E and \(\omega _{{\textit{CPEF}}} \) are its electric strength and angular frequency of its direction rotation, respectively. To apply the Neumann boundary condition mentioned above onto an elliptical boundary of the heterogeneity in Cartesian coordinates, we use a phase field method. It is a mathematical model for solving irregular boundary condition by introducing an auxiliary field \(\varphi \) [39]. Equation (1) is adapted to be

The time integral of Eq. (2) is calculated by the explicit Euler method. A central difference is applied to compute the Laplacian term \(\nabla ^{2}V\) and the gradient terms \(\nabla ({\ln \varphi })\) and \(\nabla V\). The terms \(\nabla ({\ln \varphi })\), \(\nabla V\), and \(\mathbf{E}\) are scalar fields. Thus, the terms \(\nabla ({\ln \varphi })\cdot ({\nabla V})\) and \(\nabla ({\ln \varphi })\cdot \)E mean scalar products in a two-dimensional cardiac tissue at the size of \(2\hbox { cm}\times 2\hbox { cm}\). The space and time steps are \(\Delta x=\Delta y=3.75\times 10^{-3}\hbox { cm}\) and \(\Delta t=3.125\times 10^{-4}\) ms, respectively.

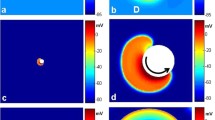

Wave emissions from elliptical heterogeneities with different orientations under a circularly polarized electric field (CPEF, in a–d) and a uniform electric field (UEF, in e–h). A CPEF is an electric field with a constant strength but a steadily rotating direction. The white arrows in a–d illustrate that the CPEF we choose without loss of generality rotates counterclockwise. Its rotating angular frequency \(\omega _{{\textit{CPEF}}} \) is 0.14 rad/ms in this and following numerical simulations. The white arrows in e-h illustrate the direction of the UEF. The electric strengths of both CPEF and UEF are 0.7 V/cm. The semi-axes of elliptical heterogeneities are at length of 0.24 cm and 0.07 cm

3 Results

As shown in Fig. 1, we use a two-dimensional cardiac tissue with an elliptical heterogeneity in the center to study the WEH by both CPEF and UEF. We define the orientation phase \(\phi \) of the ellipse as the angle from the elliptical long axis to the x axis. In Fig. 1a, e, since the long axes of elliptical heterogeneity are horizontal, \(\phi =0\). \(\phi =\pi /6\) in Fig. 1b, f. \(\phi =\pi /2\) in Fig. 1c, g. \(\phi =5\pi /6\) in Fig. 1d, h. We run 20-ms-long simulations of applying CPEF and UEF at a weak electric strength E to compare the results of the wave emissions from elliptical heterogeneities with different orientation phases. As a result, under the CPEF, all elliptical heterogeneities can emit waves. But under the UEF, only those that have vertical long axe can emit waves. It is obvious that wave emission induced by the CPEF is not affected by the ellipse orientation phase \(\phi \), but the UEF can only induce emissions within a small range of \(\phi \).

To focus on the difference of the change of the membrane potential distribution by external electric fields around the boundary of the heterogeneity and to depress the effect of an action potential on the membrane potential change, we apply very weak external electric fields to avoid the excitation. In Fig. 2, we take \(E=0.1\) V/cm for both CPEF and UEF. In the case of \(\phi =5\pi /6\), upon applying these weak external electric fields, the membrane potentials at every point of the heterogeneity boundary have been affected and reach steady distributions eventually. The areas where the membrane potentials are enhanced are called the depolarization zones. The areas where the membrane potentials are depressed are called the hyperpolarization zones. In Fig. 2, we show the distributions of the membrane potentials around the elliptical heterogeneity at different times. It demonstrates that the depolarization and hyperpolarization zones are all divided around the heterogeneity under both CPEF and UEF.

As the external electric field increases, the membrane potentials at some point of the heterogeneity boundary would exceed the threshold and excite an action potential wave [34,35,36]. In our numerical simulations, we find the point at which the membrane potential is enhanced most by the external electric field at each moment. We call this point as the maximum point in the following. In Fig. 2, we mark the maximum point as a red star. We investigate the membrane potential near the maximum point. The depolarization areas are more prominent near this maximum point than other places, as shown as deep red areas in Fig. 2, while at the opposite side of the elliptical heterogeneity, the hyperpolarization areas are more prominent, as shown as dark blue areas in Fig. 2. The curvature k along the elliptical boundary can be expressed as

where a and b represent the semi-long axis and short axis of the elliptical boundary, respectively. \(\theta \) is the phase of a point at the elliptical boundary relative to its long axis. So, if the phase of the maximum point (called as \(\theta _M )\) is known, we can calculate the maximum point curvature (called as \(k_M )\) accordingly.

The distributions of the membrane potentials around the boundary of elliptical heterogeneity under the circularly polarized electric field (CPEF, a–b) and the uniform electric field (UEF, c–-d). Both CPEF and UEF are applied at \(t=0\) ms. The electric field strength \(E_{{\textit{CPEF}}} =E_{UEF} =0.1\) V/cm. The orientation phase of the elliptical heterogeneity is chosen to be \({5\pi }/6\). The red areas represent depolarization zones, and the blue areas represent hyperpolarization zones. The dotted arrows indicate the instant directions of the CPEF and the directions of the UEF. The red stars mean the points at which the membrane potentials enhanced by the external electric field are maximum. And \(\theta _M \) is the phase indicating where the maximum point is relative to the long axis of the elliptical heterogeneity

As illustrated in Fig. 2a, b, we can see rotations of depolarizations, hyperpolarizations and maximum points due to the rotation of the CPEF, after the external electric fields are applied at \(t=0\) ms. When \(t=1\) ms, the maximum point phase \(\theta _M \) is located and measured. The curvature of the maximum point \(k_M \) is calculated based on Eq. (3) and equal to 5.89. Then, at \(t=10\) ms, the maximum point phase \(\theta _M \) is moved, and the curvature of the present maximum point \(k_M \) decreases to 1.30. As the previous study [20] demonstrated, a small boundary curvature of the heterogeneity would induce a larger redistributed membrane potential than a large boundary curvature. If we increase the electric strength of the CPEF to be 0.7 V/cm as used in Fig. 1d, the redistributed membrane potential can exceed the threshold and excite an action potential wave. But in Fig. 2c, d, the direction of the UEF is fixed; thus, the maximum point phases \(\theta _M \) remain the same from \(t=1\) ms to \(t=10\) ms. And the maximum point curvature \(k_M \) stay as large as 5.89. Even if we increase the electric strength of the UEF to be as large as 0.7 V/cm, this large boundary curvature of the heterogeneity still cannot induce a large redistributed membrane potential to excite an action potential wave. The result of this unsuccessful WEH by the UEF is shown in Fig. 1h. From the above results, one can conclude that, for a sufficiently large external electric field, whether it can redistribute the membrane potential at the boundary of the heterogeneity to exceed the excitation threshold depends on the maximum point curvature \(k_M \).

In order to get further understanding about the effect of the boundary curvature on the successful wave emission by the external electric field, we study the values of membrane potentials at every point of the elliptical heterogeneity boundary at each moment. We use two different elliptical orientation phases \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) and \(\phi =\pi /2\) to demonstrate for both CPEF and UEF. In our simulations, we measure the values of the membrane potentials at different phases of the boundary point \(\theta \) and show how they change over time t after applying the weak CPEF and the weak UEF in Fig. 3. The predominant difference of the results between the CPEF and the UEF is the highest value of the membrane potential V for all \(\theta \) and t. For different orientation phase \(\phi \) under the CPEF in Fig. 3a, b, this highest value of V remains same. The only difference is where (\(\theta )\) and when (t) it appears. Since the CPEF is rotating, it can overcome the influence of different orientation. Thus, the result of \(V=V({\theta ,t})\) in Fig. 3a where \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) is just a shift of \(V({\theta ,t})\) in Fig. 3b where \(\phi =\pi /2\) along the axes of \(\theta \) and t. But for different orientation phase \(\phi \) under the UEF in Fig. 3c, d, the highest value of V changes dramatically. Especially when \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) in Fig. 3c, the highest value of the membrane potential V is greatly depressed due to the orientation to make it hard to induce a WEH even if applying a large electric strength. Although the highest value of V when \(\phi =\pi /2\) (Fig. 3d) under the UEF looks close to the value under the CPEF, it proves that the capability of the UEF to induce the WEH is greatly influenced by the orientation of the elliptical heterogeneity.

The changes of membrane potentials V at different phases \(\theta \) of boundary points around the heterogeneity over time t. The circular polarized electric field (CPEF, a–b) and the uniform electric field (UEF, c–d) are applied at \(t=0\) ms with the weak electric strength \(E_{{\textit{CPEF}}} =E_{UEF} =0.1\) V/cm. The orientation phases of elliptical heterogeneities are \({5\pi }/6\) in (a, c) and \(\pi /2\) in (b, d)

Figure 3 also shows that the maximum membrane potential at each moment t appears at the maximum point phase \(\theta _M \). And its value (denoted as \(V_\mathrm{max } )\) would change periodically over time under the CPEF, but approach a stable value under the UEF. To clarify these changes, we measure and plot the value of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) at different time t in Fig. 4. After applying the CPEF at \(t=0\) ms, as shown in Fig. 4a, b, the values of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) increase from the resting potential and oscillate subsequently. The oscillation periods are both equal to the half of the CPEF rotation period. The peak values of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) during oscillations are \(-78.9\) mV for both heterogeneity orientations \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) and \(\phi =\pi /2\). On the other hand, the values of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) under the UEF increase with time at beginning and arrive at stable values of \(-80.4\) mV in Fig. 4c and \(-78.6\) mV in Fig. 4d. We notice that the stable value of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) when the heterogeneity orientation \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) in Fig. 4c is much smaller than the stable value of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) when \(\phi =\pi /2\) in Fig. 4d and the peak values of oscillation under the CPEF in Fig. 4a, b. This is because the curvature of the maximum point \(k_M \) in Fig. 4c is measured as 5.89, much larger than the values of 1.30, 1.24 and 1.30 in Fig. 4a, b, d, respectively. And as we mentioned above, the larger the curvature is, the lower the redistributed membrane potential would be, and the harder a wave emission is to be initiated.

The changes of the maximum membrane potentials \(V_\mathrm{max } \) over time t. The circular polarized electric field (CPEF, a–b) and the uniform electric field (UEF, c–d) are applied at the same weak electric strength as \(E_{{\textit{CPEF}}} =E_{UEF} =0.1\) V/cm. The orientations of the elliptical heterogeneity \(\phi \) are \({5\pi }/6\) in (a, c) and \(\pi /2\) in (b, d)

This also explains why action potential waves cannot be generated by the UEF in such ellipse orientations as shown in Fig. 1e, f. Because their curvatures of maximum points \(k_M \) are also too large to enhance the membrane potentials to exceed the threshold and generate action potential waves. For the cases under the CPEF, the ellipse orientation causes no problem, because the CPEF rotates. Thus, it can always change the maximum point phase \(\theta _M \) during rotation and find a small enough curvature \(k_M \) to enhance the membrane potential over the threshold and eventually generate waves.

From the above results, we find that a large curvature of the maximum point would make it hard to induce an action potential wave at a given external electric field strength. So, what if we increase the electric field strength? Especially, for the case of ellipse orientation \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) under the UEF, rather than \(E=0.1\) V/cm, how large an electric strength we need to initiate a wave emission?

The maximum membrane potentials \(V_\mathrm{max } \) over time under different electric field strengths of the circular polarized electric field (CPEF, a) and the uniform electric field (UEF, b). The external electric fields are both applied at \(t=0\) ms. The orientations of the elliptical heterogeneity \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) for both cases

To answer this question, we take the case of ellipse orientation \(\phi ={5\pi }/6\) to a further study. As shown in Fig. 5, we increase the electric field strength of both the CPEF and the UEF and check whether the maximum membrane potential \(V_\mathrm{max } \) would exceed the threshold of \(-39.9\) mV in our chosen model after applying the electric field at \(t=0\) ms. Under the CPEF in Fig. 5a, although the value of \(V_\mathrm{max } \) at the given electric field strength changes over time, the peak value of \(V_\mathrm{max } (t)\) increases with the electric field strength. There is a critical electric field strength at about 0.4 V/cm, below which \(V_\mathrm{max } \) cannot exceed the threshold \((-39.9 \hbox { mV})\) and no wave emits under the CPEF. But if we increase the strength of CPEF to be 0.5 V/cm, the peak value of \(V_\mathrm{max } (t)\) would exceed the threshold at some time and initiate an excitation. Continuing increasing the CPEF strength, the peak value of \(V_\mathrm{max } (t)\) becomes larger and larger, and the time when \(V_\mathrm{max } (t)\) reaches its peak becomes earlier and earlier. However, under the UEF in Fig. 5b, although the peak value of \(V_\mathrm{max } (t)\) also increases with the UEF strength, its critical electric field strength needs to be as large as 0.7 V/cm, much larger than the critical electric field strength 0.4 V/cm under the CPEF. In other words, the applied electric energy and the side effect of the WEH by a UEF are much larger than the ones by a CPEF.

Successful wave emissions by the circular polarized electric field (CPEF, blue solid circles) and the uniform electric field (UEF, red solid diamonds). The x-axis represents the orientation phases of elliptical heterogeneities \(\phi \). The y-axis represents the strength of the external electric fields E. (Color figure online)

Then, we study the dependence of the critical electric field to initiate a WEH under both CPEF and UEF on the orientation phase of elliptical heterogeneity \(\phi \). The results are shown in Fig. 6, where the orientation phase \(\phi \) is shown from 0 to \(\pi \) due to the rotating symmetric of \(\pi \) for the elliptical heterogeneity. We find that the critical electric field of a CPEF is only 0.5 V/cm above which any orientation phase of the elliptical heterogeneity can induce a successful WEH. In the contrast, under a UEF, only the elliptical heterogeneity with an orientation phase \({5\pi }/{18}<\phi <{13\pi }/{18}\) can induce a successful WEH. Although more and more elliptical orientation phases \(\phi \) can be induced if we continually increase the electric field strength, there are still some elliptical orientation phases at which no WEH can be initiated even at an electric field strength as large as 1.2 V/cm. This is because, in those cases of unsuccessful WEHs under the UEF, the maximum point curvature \(k_M \) is too large, and the corresponding \(V_\mathrm{max } \) cannot reach the threshold.

4 Discussions

The advantage of the CPEF over UEF to induce the WEH is also confirmed by other studies. Reference [40] finds that CPEF is better than UEF to induce WEH and suppress turbulence in chemical system. In simple models for cardiac system, as compared to UEF, Refs. [41, 42] prove that CPEF is good at liberating pinned spirals and inducing WEH from two adjacent heterogeneities, respectively.

In our simulations, we have tried different angular frequencies of CPEF from 0.065 rad/ms to 0.22 rad/ms. The simulation results prove that, within this range, different angular frequencies do not significantly change the ability of the CPEF to induce the WEH for all elliptical orientation phases. It is the same conclusion in our previous study [35]. Therefore, without loss of generality, we choose the median of the range above, i.e., 0.14 rad/ms.

5 Conclusions

In summary, the wave emission from elliptical heterogeneities using a circularly polarized electric field (CPEF) not only is immune to changing boundary curvatures and orientations of conductivity heterogeneities, but also just needs a low-voltage electric field to excite action potential waves. From a practical point of view, the more conductivity heterogeneities can emit waves, the more efficient it is to terminate arrhythmia. And considering side effects, a CPEF needs only a weak electric field strength to initiate the wave emission. Therefore, the input electric energy can be lowered and the damage to human body can be reduced. Based on the above advantages, a CPEF is a good choice at terminating arrhythmia.

References

Abubakar, I.I., Tillmann, T., Banerjee, A.: Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 385, 117–71 (2015)

Winfree, A.T.: When Time Breaks Down. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1987)

Davidenko, J.M., Pertsov, A.V., Salomonsz, R., Baxter, W., Jalife, J.: Stationary and drifting spiral waves of excitation in isolated cardiac-muscle. Nature 355, 349–351 (1992)

Gray, R.A., Pertsov, A.M., Jalife, J.: Spatial and temporal organization during cardiac fibrillation. Nature 392, 75–78 (1998)

Witkowski, F.X., Leon, L.J., Penkoske, P.A., Giles, W.R., Spano, M.L., Ditto, W.L., Winfree, A.T.: Spatiotemporal evolution of ventricular fibrillation. Nature 392, 78–82 (1998)

Jalife, J.: Ventricular fibrillation: mechanisms of initiation and maintenance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 25–50 (2000)

Cherry, E.M., Fenton, F.H.: Visualization of spiral and scroll waves in simulated and experimental cardiac tissue. New J. Phys. 10, 125016 (2008)

Karma, A.: Physics of cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 313–337 (2013)

Gao, X., Zhang, H.: Mechanism of unpinning spirals by a series of stimuli. Phys. Rev. E 89, 062928 (2014)

Gao, X., Feng, X., Li, T.C., Qu, S.X., Wang, X.G., Zhang, H.: Dynamics of spiral waves rotating around an obstacle and the existence of a minimal obstacle. Phys. Rev. E 95, 052218 (2017)

Ma, J., Wu, F.Q., Hayat, T., Ping, Z., Tang, J.: Electromagnetic induction and radiation-induced abnormality of wave propagation in excitable media. Phys. A 486, 508–516 (2017)

Wu, F.Q., Wang, C.N., Xu, Y., Ma, J.: Model of electrical activity in cardiac tissue under electromagnetic induction. Sci. Rep. 6, 28 (2016)

Zhang, Y., Wu, F.Q., Wang, C.N., Ma, J.: Stability of target waves in excitable media under electromagnetic induction and radiation. Phys. A 521, 519–530 (2019)

Koster, R.W., Chapman, F.W., Schmitt, P.W., O’Grady, S.G., Walker, R.G.: A randomized trial comparing monophasic and biphasic waveform shocks for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Am. Heart J. 147, e1–e7 (2004)

Babbs, C.F., Tacker, W.A., VanVleet, J.F., Bourland, J.D., Geddes, L.A.: Therapeutic indices for transchest defibrillator shocks: effective, damaging, and lethal electrical doses. Am. Heart J. 99, 734–738 (1980)

Santini, M., Pandozi, C., Altamura, G., Gentilucci, G., Villani, M., Scianaro, M.C., Castro, A., Ammirati, F., Magris, B.: Single shock endocavitary low energy intracardiac cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 3, 45–51 (1999)

Walcott, G.P., Killingsworth, C.R., Ideker, R.E.: Do clinically relevant transthoracic defibrillation energies cause myocardial damage and dysfunction? Resuscitation 59, 59–70 (2003)

Pumir, A., Krinsky, V.: Unpinning of a rotating wave in cardiac muscle by an electric field. J. Theor. Biol. 199, 311–319 (1999)

Takagi, S., Pumir, A., Pazo, D., Efimov, I., Nikolski, V., Krinsky, V.: Unpinning and removal of a rotating wave in cardiac muscle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 058101 (2004)

Pumir, A., Nikolski, V., Hörning, M., Isomura, A., Agladze, K., Yoshikawa, K., Krinsky, V.: Wave emission from heterogeneities opens a way to controlling chaos in the heart. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 208101 (2007)

Fenton, F.H., Luther, S., Cherry, E.M., Otani, N.F., Krinsky, V., Pumir, A., Eberhard Bodenschatz, E., Gilmour Jr., R.F.: Termination of atrial fibrillation using pulsed low-energy far-field stimulation. Circulation 120, 467–476 (2009)

Luther, S., Fenton, F.H., Kornreich, B.G., Squires, A., Bittihn, P., Hörnung, D., Zabel, M., Flanders, J., Gladuli, A., Campoy, L., Cherry, E.M., Luther, G., Hasenfuss, G., Krinsky, V.I., Pumir, A., Gilmour, R.F., Bodenschatz, E.: Low-energy control of electrical turbulence in the heart. Nature 475, 235–239 (2011)

Bittihn, P., Hörning, M., Luther, S.: Negative curvature boundaries as wave emitting sites for the control of biological excitable media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 118106 (2012)

Ji, Y.C., Uzelac, T., Otani, N., Luther, S., Gilmour, R.F., Cherry, E.M., Fenton, F.H.: Synchronization as a mechanism for low-energy anti-fibrillation pacing. Heart Rhythm 14, 8 (2017)

Weidmann, S.: Effect of current flow on the membrane potential of cardiac muscle. J. Physiol. 115, 227–236 (1951)

Sepulveda, N.G., Roth, B.J., Wikswo, J.P.: Current injection into a two-dimensional anisotropic bidomain. Biophys. J. 55, 987–999 (1989)

Sobie, E.A., Susil, R.C., Tung, L.A.: generalized activating function for predicting virtual electrodes in cardiac tissue. Biophys. J. 73, 1410–1423 (1997)

Fishler, M.G.: Syncytial heterogeneity as a mechanism underlying cardiac far-field stimulation during defibrillation-level shocks. J. Cardiovasc. Electr. 9, 384–394 (1998)

Fast, V.G., Rohr, S., Gillis, A.M., Kléber, A.G.: Activation of cardiac tissue by extracellular electrical shocks: formation of ’secondary sources’ at intercellular clefts in monolayers of cultured myocytes. Circ. Res. 82, 375–385 (1998)

Trayanova, N., Skouibine, K.: Modeling defibrillation: effects of fiber curvature. J. Electrocardiol. 31, 23–29 (1998)

Hooks, D.A., Tomlinson, K.A., Marsden, S.G., LeGrice, I.J., Smaill, B.H., Pullan, A.J., Hunter, P.J.: Cardiac microstructure: implications for electrical propagation and defibrillation in the heart. Circ. Res. 91, 331–338 (2002)

Woods, M.C., Sidorov, V.Y., Holcomb, M.R., Beaudoin, D.L., Roth, B.J., Wikswo, J.P.: Virtual electrode effects around an artificial heterogeneity during field stimulation of cardiac tissue. Heart Rhythm 3, 751–752 (2006)

Plonsey, R.: The nature of sources of bioelectric and biomagnetic fields. Biophys. J. 39, 309–312 (1982)

Feng, X., Gao, X., Pan, D.-B., Li, B.-W., Zhang, H.: Unpinning of rotating spiral waves in cardiac tissues by circularly polarized electric fields. Sci. Rep. 4, 4381 (2014)

Feng, X., Gao, X., Tang, J.-M., Pan, J.-T., Zhang, H.: Wave trains induced by circularly polarized electric fields in cardiac tissues. Sci. Rep. 5, 13349 (2015)

Pan, D.-B., Gao, X., Feng, X., Pan, J.-T., Zhang, H.: Removal of pinned scroll waves in cardiac tissues by electric fields in a generic model of three-dimensional excitable media. Sci. Rep. 6, 21876 (2016)

Luo, C.H., Rudy, Y.: A model of the ventricular cardiac action potential depolarization, repolarization, and their interaction. Circ. Res. 68, 1501–1526 (1991)

Qu, Z.L., Xie, F.G., Garfinkel, A., Weiss, J.N.: Origins of spiral wave meander and breakup in a two-dimensional cardiac tissue model. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 28, 755–771 (2000)

Fenton, F.H., Cherry, E.M., Karma, A., Rappel, W.: Modeling wave propagation in realistic heart geometries using the phase-field method. Chaos 15, 013502 (2005)

Zhao, Y.-H., Lou, Q., Chen, J.-X., Sun, W.-G., Ma, J., Ying, H.-P.: Emitting waves from heterogeneity by a rotating electric field. Chaos 23, 033141 (2013)

Chen, J.X., Peng, L., Ma, J., Ying, H.P.: Liberation of a pinned spiral wave by a rotating electric pulse. Europhys. Lett. 107, 38001 (2014)

Chen, J.-X., Zhang, H., Qiao, L.-Y., Liang, H., Sun, W.-G.: Interaction of excitable waves emitted from two defects by pulsed electric fields. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 54, 202–209 (2018)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants Nos. 11647055 and 11705114 and by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant No. GK201802017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, X., Gao, X. Wave emission from heterogeneities with changing boundary curvature and orientation by a circularly polarized electric field in cardiac tissues. Nonlinear Dyn 98, 1919–1927 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-019-05296-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-019-05296-9