Abstract

We use the incremental harmonic balance (IHB) method to analyse the dynamic stability problem of a nonlinear multiple-nanobeam system (MNBS) within the framework of Eringen’s nonlocal elasticity theory. The nonlinear dynamic system under consideration includes MNBS embedded in a viscoelastic medium as clamped chain system, where every nanobeam in the system is subjected to time-dependent axial loads. By assuming the von Karman type of geometric nonlinearity, a system of m nonlinear partial differential equations of motion is derived based on the Euler–Bernoulli beam theory and D’ Alembert’s principle. All nanobeams in MNBS are considered with simply supported boundary conditions. Semi-analytical solutions for time response functions of the nonlinear MNBS are obtained by using the single-mode Galerkin discretization and IHB method, which are then validated by using the numerical integration method. Moreover, Floquet theory is employed to determine the stability of obtained periodic solutions for different configurations of the nonlinear MNBS. Using the IHB method, we obtain an incremental relationship with the frequency and amplitude of time-varying axial load, which defines stability boundaries. Numerical examples show the effects of different physical and material parameters such as the nonlocal parameter, stiffness of viscoelastic medium and number of nanobeams on Floquet multipliers, instability regions and nonlinear amplitude–frequency response curves of MNBS. The presented results can be useful as a first step in the study and design of complex micro/nanoelectromechanical systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Most dynamic stability studies in the literature are considering single or double-micro/nanostructure-based systems [1,2,3,4]. Investigation of the nonlinear dynamic behaviour of such systems has been an exciting perspective in the last decade due to possible applications in design procedures of different micro/nanoengineering systems [5], especially when these systems are aimed to be exploited as vibrating nanodevices such as resonators, nanosensors, or other nanoelectromechanical systems. However, it has been shown that organized nanostructure architectures made of vertically aligned forests, yarns, and sheets of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) give an exciting perspective to scale up the properties of individual CNTs and realize new functionalities [6]. The lack of reliable nonlinear dynamic models of multiple-nanostructure-based systems makes a future investigation in this field as an attractive task for researchers. A seminal idea of this work is to fill this gap in the literature and propose new models and procedures of a solution to investigate the dynamic stability of the geometrically nonlinear multiple-nanobeam system (MNBS). The presented model of MNBS consists of multiple individual simply supported nanobeams that are parallel to each other and placed into a viscoelastic medium. In general, such model can represent some nanocomposite material composed of vertically aligned CNTs array placed in some polymer. Therefore, the presented model of the nonlinear MNBS might be important to investigate the aligned arrays of CNTs [7] and CNT/polymer composites [8], especially stability of CNTs embedded in the polymer matrix. In addition, due to their remarkable physical and chemical characteristics, various applications and mathematical models of CNTs are suggested in the literature [9]. Based on experimental results, it is shown that small-scale effects play a significant role in the static and dynamic behaviour of micro/nanostructures. Since models based on classical continuum theory are scale-free, they need to be modified introducing some new assumptions in order to take into account size effects that are present at small scales. Eringen [10, 11] extended the classical continuum theory by introducing integral and differential forms of constitutive equations with a single material parameter, such that it takes into account forces between atoms and internal length scale. Moreover, it has been shown that the results obtained by using the nonlocal continuum models are in good agreement with the results obtained via molecular dynamics simulations. Many authors have analysed the mechanical behaviour of different types of nanostructures within the framework of nonlocal continuum mechanics.

A pioneering study where nonlocal elasticity theory is proposed to model micro/nanostructures is the work by Pedinson et al. [12]. They analysed the static and dynamic behaviour of a simple micro/nanobeam and proposed a possible application to real MEMS and NEMS. Reddy [13,14,15] has derived new equations of motion for Euler–Bernoulli, Timoshenko, Reddy and Levinson beam theories based on the Eringen’s nonlocal elasticity theory and then obtained analytical solutions for bending, vibrations, and buckling response of beams for simply supported boundary conditions. The new shear deformation beam theory proposed by Huu-Tai [16] is used to analyse the free vibration and stability of short nanobeams using Eringen’s nonlocal elasticity theory. Aydogdu [17] employed the Euler–Bernoulli, Timoshenko, Levinson, Reddy, and Aydogdu beam theories to analyse the bending, buckling, and vibration of nanobeams in an analytical manner. Ansari et al. [18, 19] compared results obtained from nonlocal continuum mechanics with the results obtained by molecular dynamic simulations for simple models of nanostructures and concluded that the results obtained from both theories are in good agreement. More complex nanoscale systems consist of two and more organized nanostructures such as rods, beams, and plates, which are usually coupled through some medium. The dynamic behaviour of such systems is interesting to observe and it is still not fully explored in the literature. A double-nanostructure-based system is the simplest model of a coupled multiple-nanostructure systems, which can be composed of two nanobeams, nanorods or nanoplates coupled through a medium with elastic or viscoelastic properties. Murmu and Adhikari conducted detailed vibration studies of a double-nanorod, nanobeam, and nanoplate systems [20,21,22,23], where partial differential equations of motion are obtained based on the D’ Alembert’s principle and nonlocal elasticity theory and solved by using analytical methods. They investigated the influence of small-scale effects and other physical parameters on natural frequencies and critical buckling loads and compared analytical results with results obtained by molecular dynamics simulations. One of the first dynamic behaviour studies of multi-layered graphene sheet system is the paper by He et al. [24] and Liew et al. [25], where the authors derived an explicit formula for natural frequencies by utilizing the classical elasticity model. Using the methodology that was proposed for chain-like mechanical systems by Rašković [26] and multiple coupled structural elements by Hedrih [27], Karličić et al. [28] presented a straightforward method to obtain analytical solutions for natural frequencies and critical buckling loads of multiple nanorods, nanobeams, and nanoplates systems based on the Eringen’s nonlocal elasticity theory and trigonometric method. To this time, the mechanical behaviour of different nanostructures such as the longitudinal vibration of nanorods [29], transverse vibration of nanobeams [30,31,32], nanoplates [33] and nanoshells [34] with elastic properties are given in the literature.

Forced and parametric vibration problems of complex coupled nanostructure-based systems such as coupled nanobeams, nanorods, nanoplates have attracted much attention of the scientific community. Simsek [35] investigated the influence of a moving load on different types of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Karaoglu and Aydogdu [36] investigated the forced vibration of carbon nanotubes via nonlocal Euler–Bernoulli beam model. Ansari et al. [37, 38] analysed the forced vibration of nanobeams as mechanical models of carbon nanotubes by using different numerical technics and compared the results with those obtained by the molecular dynamic simulations. In addition, Kiani [39,40,41,42] has examined the influence of different physical fields and shear effects on the free and forced vibration response of nanoscale systems composed of multiple nanobeams coupled in membrane and forest configurations. Also, Kiani [43,44,45] conducted several studies on the influence of moving loads on double-carbon nanotube system based on the nonlocal elasticity theory. Arani et al. [46] investigated the nonlinear dynamic stability of a double-graphene sheet with integrated actuators and sensors based on the Gurtin–Murdoch elasticity theory. Further, in series of papers Wang et al. [47, 48] investigated the nonlinear behaviours of double-nanoplate systems for forced and parametric excitations. Recently, Pavlović et al. [49] observed the stochastic stability problem by determining the stability boundaries and regions of almost sure stability of a linear multi-nanobeam system embedded in a viscoelastic medium by using the Monte Carlo simulation method.

In general, dynamic stability analysis of nanobeam-like structures can play a significant role in design procedures of future nanodevices. For axially loaded nanobeams, where loads are time-dependent harmonic functions, a failure due to dynamic instability might occur for much smaller amplitudes of load than the failure induced by static buckling. These instability conditions usually lead to the failure of micro/nanodevices. Based on that fact, authors usually intend to analyse stability regions caused by primary parametric resonance, where the frequency of excitation is two times larger than the first natural frequencies of MNBS [50, p. 23]. Therefore, the main aim of this paper is to extend the previous studies by investigating the dynamic stability of more complex systems such as the nonlinear MNBS and to explore its primary resonance state. In addition, investigation of the influence of small-scale parameter on the stability of periodic solutions and instability regions is a very important task for the design of different types of micro/nanodevices.

It is well known that CNT/polymer composites can be observed as materials with viscoelastic properties [51,52,53]. Based on experiments and complex modulus characterization results [52], one can obtain unique properties of composite materials with aligned carbon nanotubes embedded in the polymer matrix. Knowing storage and loss modules is the first step in the identification of parameters of chosen viscoelasticity model to represent such materials. In addition, it is confirmed that in CNT/polymer composites, relaxation time and viscosity of polymers are temperature-dependent quantities [53], which can be easily obtained from complex modulus under the assumption of isothermal deformation [54]. On the other side, a model of MNBS embedded in the elastic medium is suitable to describe the van der Waals interactions between adjacent nanobeams, where values of the stiffness coefficient of the elastic medium can be determined from van der Waals forces using the methodology from the literature [39,40,41,42].

Up to this point, no investigation of the dynamic stability of the nonlinear MNBS has been carried out within the framework of nonlocal elasticity theory. In the present paper, we carry out the semi-analytical procedure based on the incremental harmonic balance (IHB) method to find periodic solutions and instability regions of the axially loaded system of m coupled nonlinear nanobeams embedded in the viscoelastic medium. We assume that nanobeams are having the same material and geometric properties as well as boundary conditions. By considering the Euler–Bernoulli beam theory, nonlocal constitutive relation and von Karman nonlinear strains, we obtain a system of m nonlinear partial differential equations of motion. Single-mode Galerkin discretization will be employed to obtain a system of m nonlinear differential equations that will be solved using the IHB method in order to obtain semi-analytical periodic solutions of the nonlinear MNBS for different configurations. Moreover, the stability of periodic solutions will be examined by introducing the Floquet theory. The parametric study will be conducted to study the influence of different parameters on the regions of instability, nonlinear amplitude–frequency response curve and Floquet multipliers. This study can be a starting point for investigation of more complex behaviour such as chaos in nonlinear MNBS.

2 Problem formulation

2.1 Formulation of the dynamic equations of motion

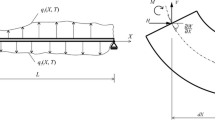

Let us consider the system formed by the set of straight and parallel nanobeams with geometric nonlinearity, which are embedded in a viscoelastic medium and subjected to time-dependent axial compressive loads \(F_1 \left( t \right) =F_2 \left( t \right) =\cdots =F_m \left( t \right) =F \left( t \right) \), Fig. 1. All nanobeams in MNBS are having the same material and geometric properties such as elastic modulus E, mass density \(\rho \), uniform cross sections of area A and moments of inertia I. Nanobeams in MNBS are referred to as nanobeam 1, nanobeam 2 and so on until the m-th nanobeam. The transverse displacement of the i-th nanobeam is \(w_i \left( {x,t} \right) , i=1,2,3\ldots m\). This study is limited to the case of the Euler-Bernoulli’s beam model with simply supported boundary conditions (see Fig. 1). It considers only MNBS coupled in the clamped chain system, where the first and the last nanobeam in the system are coupled with a fixed base through a viscoelastic medium of stiffness k and viscosity b. Other nanobeams in MNBS are also coupled through the viscoelastic medium of stiffness per length k and viscosity b.

In order to explore the dynamic stability of nanoscale structures, we first need to consider size effects that might significantly change dynamic properties of nonlinear dynamic systems. For this purposes, modified continuum theories shown to be a reliable tool for modelling of nanoscale systems [13,14,15]. Eringen [10, 11] derived a new constitutive relation in the integral form and later on in the differential form, based on the assumption that the stress at some point of an elastic body is a function of strains at all other points of that body. The aforementioned differential form of the nonlocal constitutive relation for one-dimensional case is given as

where E is Young’s modulus of the nanobeam, \( \mu =\left( {e_0 a} \right) ^{2}\) is the nonlocal parameter (length scale) with a denoting the internal characteristic length and \(e_0 \) denoting the dimensionless material constant. Further, \(\sigma _{xx} \) is the normal nonlocal stress, whereas the von Karman nonlinear strain–displacements relation is given as follows:

In the literature, it is shown that the exact value of the nonlocal parameter is scattered and depends on applied boundary conditions, material and geometric properties of nanostructures.

The most common method for determination of the nonlocal parameter for simple nanostructures is the fitting procedure based on molecular dynamics simulations. As mentioned previously, the nonlocal parameter \( \mu =\left( {e_0 a} \right) ^{2}\) is determined by the internal characteristic length a (lattice parameter, granular size or distance between C–C bounds that is for SWCNT a =1.42 (Å), e.g. see [55]) and constant \(e_0 \), whose value is different for each material. Eringen [10] obtained the value of nonlocal parameter by comparing the dispersion curves of plane waves from nonlocal model with those obtained by the atomic Born–Karman model of lattice dynamics. The author has found that the maximum difference of 6% is obtained for the value of constant \(e_0 = 0.39\). Furthermore, the value of key parameter \(e_0 \) can be found by comparing the results for frequencies found by the nonlocal elasticity model with those from the MD simulations. In order to analyse the multi-wall carbon nanotube-based system, Sudak [56] proposed that \(e_0 = 112.7\), for the case when the, nonlocal parameter is \(\left( {e_0 a} \right) = 1.50 \times 10^{-8}\) (cm) and \(a =1.42\) (Å). In the paper proposed by Zhang et al. [57], the authors have estimated the value of material constant \(e_0 \approx 0.82\) by matching the results from nonlocal continuum model with the results from molecular dynamics simulations given in Sears and Batra [58]. Ansari et al. [19, 59, 60] published a series of papers where values of nonlocal parameter are calibrated based on molecular dynamic simulations. The authors have employed the NanoHive simulator to perform quasi-static molecular dynamics simulations on SWCNTs with different chirality, aspect ratios, and boundary conditions. By using the nonlinear least-square fitting procedure, fundamental frequencies are obtained for different nonlocal beam theories and matched with those calculated from MD simulations, where \(\left( {e_0 a} \right) \) is set as the optimization variable for each nonlocal beam model. They obtained the values of nonlocal parameter \(\left( {e_0 a} \right) \) from the fitting procedure for both, armchair and zigzag SWCNTs, taking into account different boundary conditions. It is shown that values of nonlocal parameter are ranging from 0.13 to 1.42 for different nanobeam theories and boundary conditions. Based on previous results, in this study we adopted that the values of nonlocal parameter goes in the range \(\left( {e_0 a} \right) =0-2 \left( {\mathrm{nm}} \right) \).

The equations of motion can be expressed in terms of displacements \(w_i \left( {x,t} \right) \), where by taking into account nonlocal constitutive relation (1) and von Karman nonlinear strain–displacements relation (2) in the D’ Alembert’s principle, we obtain the following equation of motion for the i-th nanobeam [59],

and clamped chain conditions as follows:

where the axial load is \(F=F_0 +F_1 \cos 2{\Omega }t\) with amplitudes of static \(F_0 \) and dynamic part \(F_1 \) of axial load, while \({\Omega }\) is the frequency of the dynamic part of axial load.

From Eqs. (3) and (4), we obtain equations of motion of the clamped chain system, shown in Fig. 1, as:

Mathematical expressions for initial and boundary conditions of simply supported Euler-Bernoulli nanobeams, of the same length L, are given as follows:

*initial conditions

*boundary conditions for simply supported (S–S) nanobeams

3 Galerkin discretization method

Now, we can reduce the system of m nonlinear partial differential equations of motion (5) to the system of m nonlinear ordinary differential equations by using the Galerkin discretization, where obtained equations represent only the time-varying part of the solution. The first mode of approximation is assumed to be in the following form:

in which \(r=\sqrt{\frac{I}{A}}\) is the radius of gyration of the cross section, \(f_i \left( t \right) \) is the corresponding time function and \(\phi \left( x \right) \) is the linear mode shape function determined from the boundary conditions. The mode shape function for corresponding boundary conditions of MNBS is given as follows:

Inserting Eq. (7) into (5), multiplying the results by corresponding linear mode shape function Eq. (8), and then integrating them over the length of the nanobeam, we obtain a set of m nonlinear ordinary differential equations expressed in terms of corresponding time functions \(f_i \left( t \right) \) as follows:

where \(\omega _L \) is the natural frequency of corresponding linear system, \(\upsilon \) is the damping ratio and \(\gamma \) is the nonlinear stiffness

and \(\omega _K^2 , \omega _F^2 \) and \({\Lambda }\) are reduced constants given as follows:

In the following, we introduce the IHB method to determine the periodic solutions of the presented system of m nonlinear ordinary differential equations, instability regions of the nonlinear MNBS and Floquet multipliers. It should be noted that stability of determined periodic solutions of the nonlinear MNBS is studied by using the Floquet stability theory.

4 Instability regions and periodic solution: IHB method

Lau et al. [61] developed the methodology for the IHB method which is later on applied to different problems [62,63,64,65,66]. In general, IHB is the semi-analytical method that can be used for finding the solutions of differential equations appearing in mathematical models of various problems in mechanics. In order to obtain instability regions and periodic solutions of the system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (9), we use the IHB method to obtain iterative relationships with frequency, response amplitudes and excitation amplitude of time-varying axial load. First, one should introduce a new time scale \(\tau = \Omega t\) into Eq. (9) to obtain the system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations in the following form:

Dividing Eq. (15) with \(\omega _L^2 \), one can obtain a new form of Eq. (11) as follows:

where the values of the frequency \(\Omega \) depends on the configuration of the nonlinear MNBS and \(\tilde{\Lambda } =\frac{{\Lambda }}{\omega _L^2 }\). Now, we introduce the incremental relations for \(f_i \left( \tau \right) , {\Omega }\), and \(\tilde{\Lambda } \), where \(f_{i0} \left( \tau \right) \), \({\Omega }_0\) and \(\tilde{\Lambda } _0 \) denotes a known vibration state, and \({\Delta }f_i \left( \tau \right) \), \({\Delta \Omega }\) and \({\Delta }\tilde{\Lambda } \) are corresponding increments of amplitude, frequency and amplitude of excitation load, respectively, for neighbouring vibration state, which is given as follows:

Substituting relations (13) into Eq. (12) and neglecting higher-order terms, a linearized incremental relation can be expressed as

Assuming the periodic solutions of Eq. (14), the functions \(f_{i0} \left( \tau \right) \) and \({\Delta }f_i \left( \tau \right) \) can be taken as Fourier series in the following forms:

where

Inserting Eq. (15) into the system of Eq. (14) and applying the Galerkin procedure presented in [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], we obtain the system of linear algebraic equations in terms of unknown increments of amplitudes \(\Delta {{\varvec{A}}}_{i}\) in the following form:

where

In Eq. (17), corrective vector term \(\left[ {{\varvec{R}}} \right] \,\left\{ {{\varvec{A}}} \right\} \) tends to zero when the values of \(f_{i0} \left( \tau \right) , {\Omega }_0 \) and \(\tilde{\Lambda } _0 \) tends to exact solutions. Set of linearized algebraic equations presented in Eq. (17) can be solved incrementally by starting from any known linear solution using \(\tilde{\Lambda }\)-incrementation procedure.

Since the system of Eq. (17) has two more unknowns than the number of equations in the system, we need to set one value of Fourier coefficients in Eq. (15) to be constant and corresponding increment equal to zero. In the \(\tilde{\Lambda } \)-incrementation process, the \({\Delta }\tilde{\Lambda } \) is an active increment whereby giving the initial values of \({{\varvec{A}}}_i\), \({\Omega }_0 \) and \(\tilde{\Lambda } _0 \) one can obtain principal instability regions that are bounded by two boundaries. When using the Newton–Raphson method for solving the system (17), we need to do the following two steps. First, we determine the initial values of \({{\varvec{A}}}_i\), \({\Omega }_0 \) and \(\tilde{\Lambda } _0\), set \(a_{i1} =\mathrm{Const.}\), \(b_{i1} = \mathrm{Const.}, \quad \Delta a_{i1} =0\), \(\Delta b_{i1} =0\) and consider \({\Delta }\tilde{\Lambda } \) as an active increment during simulation to obtain the same number of equations and unknowns in Eq. (17). Second, by using the iterative Newton–Raphson method, we solve the incremental relation (17), where the results for \(\Delta {{\varvec{A}}}_i \) and \(\Delta {\Omega }\) are obtained iteratively until the residue Euclidian norm \({\vert }\left[ {{\varvec{R}}} \right] \left\{ {{\varvec{A}}} \right\} {\vert }\) is smaller than a preset tolerance for \(\left\{ {{{\varvec{A}}}_i } \right\} ^{p+1}=\left\{ {{{\varvec{A}}}_i } \right\} ^{p}+\left\{ {\Delta {{\varvec{A}}}_i } \right\} ^{p+1}\) and \({\Omega }_0^{p+1} ={\Omega }_0^p +{\Omega }^{p+1}\). In the next step, the initial value of \(\tilde{\Lambda } \)—incrementation procedure is \(\tilde{\Lambda } _0 +{ \Delta }\tilde{\Lambda } \), and we repeat an iterative procedure until the residue Euclidian norm \({\vert }\left[ {{\varvec{R}}} \right] \left\{ {{\varvec{A}}} \right\} {\vert }\) is smaller then a preset tolerance. The process is repeated until \(\tilde{\Lambda } _0 \) reaches the set value.

In order to obtain periodic solutions of the system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (12), we reduce the incremental relations to

and for a periodic solution we obtain

where

Then, the incremental relation (17) becomes

5 Stability of the periodic solution: Floquet theory

In order to analyse the stability of periodic solutions of the system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (9), we consider the Floquet theory in \(\mathbb {R}^{N}\). Now, we write the system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations for nonlinear MNBS in general form as follows:

where \({{\varvec{f}}}^{ }=\left[ {f_1 \left( \tau \right) , f_2 \left( \tau \right) ,\ldots f_N \left( \tau \right) } \right] \) is N-dimensional displacement vector and \({{\varvec{f}}}'=d{{\varvec{f}}}/\mathrm{d}\tau \).

Introducing small perturbations \({{\varvec{\Delta }}}{{\varvec{f}}}\left( \tau \right) \) in a neighbourhood of the periodic solution \({{\varvec{f}}}_\mathbf{0} \left( \tau \right) \), i.e. by letting

we can analyse the stability of periodic solutions by analysing the system of linear equations with variable coefficients in terms of small perturbations \({{\varvec{\Delta }}}{{\varvec{f}}}\left( \tau \right) \). Introducing Eq. (22) into the system of Eq. (21) and after linearization, we obtain the system of linear differential equations as follows:

where \({{\varvec{f}}}_\mathbf{0} \left( \tau \right) \) is the periodic solution determined by considering the IHB method. It should be noted that Eq. (23) represents the system of perturbed equations around known solutions \({{\varvec{f}}}_\mathbf{0} \left( \tau \right) \). The stability characteristics of known periodic solutions are found through the multi-variable Floquet theory.

We introduce state-space variables where

for \({{\varvec{Y}}}\left( \tau \right) =\left[ {{{\varvec{\Delta }}}{{\varvec{f}}}\,, {{\varvec{\Delta }} {{\varvec{f}}}}^{\prime }} \right] ^\mathrm{T}\) and \({{\varvec{G}}}\left( \tau \right) \) denoting the periodic matrix.

Based on the Floquet theory [68,69,70], the stability criteria for determined periodic solutions of MNBS is related to eigenvalues of the matrix \({{\varvec{M}}}\) (Floquet multipliers), which is the transition matrix and the real parts of characteristic exponents (Floquet exponents). In the case when all values of Floquet multipliers are located inside the unit circle centered at the origin of the complex plane, the periodic solutions are stable or asymptotically stable. However, when the values of Floquet multipliers are out of the unit circle, then the periodic solutions are unstable [68,69,70].

In order to numerically determine the Floquet multipliers, we assume that period \(T=2\pi \) of \({{\varvec{f}}}_\mathbf{0} \left( \tau \right) \) is divided into \(N_k \) subintervals, in which the k-th interval is \({\Delta }_k =\tau _k -\tau _{k-1} \) for \(\tau _k =kT/N_k \). Moreover, \({{\varvec{G}}}\left( \tau \right) \) is the continuous matrix with respect to \(\tau \), so in the k-th interval it can be replaced by the constant matrix provided in the case when \(N_k \) is chosen to be sufficiently large

Now, we can write the transition matrix in the following form:

where \(N_j \) denotes the number of terms in the approximation of the constant matrix \({{\varvec{G}}}_k\). From the transition matrix \({{\varvec{M}}}\), one can obtain Floquet multipliers as eigenvalues of Eq. (26) in the following form:

For the nonlinear MNBS consisting of m nanobeams, the periodic matrix \({{\varvec{G}}}\left( \tau \right) \) has the following form:

where \(P_i , \left( {i=1,2,\ldots m} \right) \), R and T are defined as

From the relation (28), it is easy to obtain a system matrix for a specific configuration of the nonlinear MNBS.

6 Numerical results

This section is divided into four parts. First, we show a comparative study where results for periodic solutions of the system of nonlinear differential equations obtained by employing the IHB method are validated with the results from the Runge–Kutta method (ode45-Matlab). Afterwards, we analyse the stability of periodic motions of the nonlinear MNBS by employing the Floquet stability theory. In that context, we show Floquet multipliers as functions of different physical parameters. In the second part of this section, we show the stability boundaries and instability regions determined by the IHB method for different configurations of the nonlinear MNBS. The free nonlinear vibrations of MNBS are analysed in the third part, where frequency response curves are shown for different numbers of nanobeams in the system. The validation study is presented in the last subsection.

The system of m nonlinear differential equations (9) represents a mathematical model of the nonlinear MNBS that is vibrating under the influence of time-varying axial loads with considered initial conditions. In the case of larger systems, such as the nonlinear MNBS, it is difficult to find system responses using only analytical methods. In addition, in a large number of nanoengineering applications, the amplitude of vibration is not small and for such systems, we can only use numerical or approximate technics. It should be noted that IHB method has several advantages in comparison with classical approximated methods. First, there are no limitations such as small exciting parameters or weak nonlinearities and second, it is easy for computer implementation. Because of these facts, we determine periodic solutions of the nonlinear MNBS without introducing any limitations such as the bookkeeping parameter.

6.1 Periodic solutions and stability

In this study, we consider several different cases of MNBS with \(m=1, 3, 5\) nanobeams and for different initial conditions. We adopted the material and geometric properties for nanobeams in MNBS corresponding to the properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes as: Young’s modulus \(E=1.1 \hbox { TPa}\), density \(\rho =1300 \frac{\mathrm{kg}}{\mathrm{m}^{3}} \), length \(L=45 \hbox { nm}\), inner \(d_1 =3\,\hbox { nm}\) and outer \(d_0 =2.32 \hbox { nm}\) diameters of the nanotube. For the numerical purposes, we use the value of elastic coefficient of the medium as \(k=10^{8}\,({\hbox {N}/\hbox {m}^{2}})\), while influence of damping coefficient is almost neglected and small value of \(b=10^{-6}\,({\hbox {Ns}/\hbox {m}^{2}})\) is adopted.

In order to illustrate the accuracy of the proposed IHB methodology, we compare the obtained results with the results from the Runge–Kutta method in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, where a fine agreement of the results is achieved. These figures show time response functions of the first nanobeam and periodic orbits of each nanobeam for different configurations of the nonlinear MNBS. Figure 2 shows periodic orbits of the special case of the nonlinear MNBS consisting of a single nanobeam, which is the case very often analysed in the literature. However, in Figs. 3 and 4, one can observe periodic orbits of the nonlinear MNBS consisting of three- and five-coupled nanobeams. We can notice that the periodic solutions strongly depend on initial conditions.

Now, we can investigate the stability of determined periodic solutions of the nonlinear MNBS subjected to axial time-dependent loads (Figs. 5, 6, 7). By considering the Floquet theory, we can obtain Floquet multipliers for different configurations of the nonlinear MNBS consisting of one, three and five nanobeams in the system. By calculating the Floquet multipliers and tracing their evaluation, we predict the stability or identify bifurcations of the presented system. For stability of the periodic solution, Floquet multipliers must be centred within the unit circle with the origin in the centre of the complex plane. However, if the values of Floquet multipliers leave the unit circle, we can predict bifurcation according to [71]. For particular values of material parameters and initial conditions, we consider the iterative equation (20) and obtain the following stable periodic solutions wherein the stability of the trajectory is confirmed by using the Floquet theory and above-described iterative procedure [69, 70]. We set the values of \(N_k =10^{4}\) and \(N_j =5\) in the relation (26) showing Floquet multipliers as functions of amplitudes of axial loads and nonlocal parameter, Figs. 5, 6 and 7, for different configurations of the nonlinear MNBS.

The influence of axial load amplitude on the Floquet multipliers for the special case of MNBS consisting of a single nanobeam is shown in Fig. 5. Moreover, we get Floquet multipliers as complex numbers, where real parts are shown in Fig. 5a and imaginary parts in Fig. 5b. By increasing the value of axial load \(\tilde{\Lambda } \), both parts of the Floquet multipliers remain within the unit circle of the complex plane, as shown in Fig. 5c. Based on that fact, we can conclude that obtained periodic solutions for the nonlinear system are stable for both values of the nonlocal parameter. It should be noted that the real parts of Floquet multipliers decrease for an increase in the nonlocal parameter, while the imaginary parts increases.

Figure 6 shows three values of Floquet multipliers as functions of the nonlocal parameter and amplitude of axial load for the nonlinear MNBS consisting of three nanobeams. From obtained curves, it can be observed that the influence of the amplitude of axial load on the Floquet multipliers is not a smooth function coming out of the unit circle in the complex plane, as shown in Fig. 6g, i. Based on that fact, we can conclude that the periodic solution of the third nanobeam in MNBS is unstable. For the Floquet multipliers regarding the first and the second nanobeam, we can observe that obtained periodic solutions are stable, as shown in Fig. 6c, f. It should be noted that the nonlocal parameter has a significant influence on the first two Floquet multipliers while for the third one it almost vanishes, as shown in Fig. 6i.

The Floquet multipliers determining the stability of the nonlinear MNBS composed of five nanobeams are shown in Fig. 7. We can observe a very interesting behaviour of Floquet multipliers with a significant dependence on the nonlocal parameter. From obtained results, we can notice that only the fourth and the fifth nanobeam in MNBS are having stable periodic solutions with the values of Floquet multipliers remaining within the unit circle of the complex plane, as shown in Fig. 7l, p. However, other periodic solutions of MNBS are unstable, where the values of the Floquet multipliers are out of the unit circle, as shown in Fig. 7c, f, i. From the physical point of view, we can conclude that the number of nanobeams decreases the overall stiffness of the MNBS and this fact lead to the reduction of the system stability.

6.2 Instability regions

Figures 8, 9 and 10 show instability regions of the nonlinear MNBS obtained by using the IHB method. It should be noted that boundary curves of instability regions are determined by using the \(\lambda \)-incrementation, where the value of the increment is \({\Delta }\lambda =0.001\), with five cosine and five sine harmonic terms. The boundary lines leaning to the left are determined by using the sine terms, while boundary lines leaning to the right are defined by the cosine terms only. When considering incremental relations to determine instability regions, we can examine cases with small and large initial amplitudes as well. Small initial amplitudes lead to the linear case while large values of initial amplitudes lead to the nonlinear case, for the same values of the excitation force amplitude. Both cases are explored, where amplitudes are shown as functions of the amplitude of axial load, a number of nanobeams and different physical parameters such as stiffness coefficients (Fig. 8), the nonlocal parameter (Fig. 9) and the amplitude of static axial load (Fig. 10). The values of initial amplitudes for the incremental equation (17) are given as \(a_{i1} =0.1\) and \(b_{i1} =0.1\) for the linear case and \(a_{i1} =3\) and \(b_{i1} =3\) for the nonlinear case. Applying the Newton–Raphson procedure, where incrementation process starts from \(\lambda =0 \) to \(\lambda =1\), we can investigate the instability region of the nonlinear MNBS. For the present analysis, we adopted the same material and geometrical properties of nanobeams as in the previous case. The instability regions are represented by the areas that are surrounded by two stability boundaries.

Figure 8 shows the influence of stiffness coefficient k and the number of nanobeams on the instability regions of the linear and nonlinear cases. It can be concluded that an increase in stiffness coefficient k leads to narrowing of instability regions while an increase in the number of nanobeams in MNBS leads to an increase in instability regions. From the physical point of view, an increase in the number of nanobeams decreases the overall stiffness of the system and dynamic system is becoming more unstable. From the nonlinear case (Fig. 8b), we can notice that different configurations of MNBS shifts the instability regions, which is the consequence of the system’s nonlinearity.

The influence of the nonlocal parameter on instability regions of MNBS for different configurations is shown in Fig. 9. One can observe that the influence of the nonlocal parameter on instability regions is small for small values of the amplitude of axial load in the linear case. However, in the nonlinear case, the nonlocal parameter has a significant influence on instability regions. As expected, we have shifts of instability regions of MNBS for a different number of nanobeams in the system. The amplitudes of nonlinearity and overall stiffness of MNBS will dictate shifts of instability regions.

The last Fig. 10 illustrates the effects of the amplitude of static axial load on instability regions of MNBS. An increase in the amplitude of static axial load increases the instability regions. This increase is smaller for the nonlinear case than for the linear one. In addition, this effect occurs as a result of an increase in the overall stiffness of the system. For all the presented cases, an increase in the amplitude of axial load \(\tilde{\Lambda } \) leads to an increase in instability regions and the system becomes more unstable.

In a general case, we can conclude that change of a number of nanobeams in MNBS affects its instability regions in such a manner that these regions are expanding for an increase in the parameter m and small initial amplitudes. On the other side, for larger initial amplitudes, we can notice that the effect of a number of nanobeams goes in two directions. First, the instability regions are shifted relative to the case of small initial amplitudes and second, instability regions are increasing for a change of a number of nanobeams in the system. From the mechanical point of view, we can conclude that the overall stiffness of MNBS is reduced when increasing the number of nanobeams, which consequently results in reduced stability of the system.

6.3 The free nonlinear vibration of MNBS

In order to analyse the free nonlinear vibration of MNBS, amplitude–frequency responses for different configurations of MNBS obtained by using the IHB method are presented in Figs. 11 and 12. It should be noted that nonlinear amplitude–frequency curves are determined by using the \({\Delta }b_1 \)-incrementation, where the value of the increment is \({\Delta }b_1 =0.001\), using the five odd cosine terms [67]. In this subsection, we will neglect the influence of the axial load and damping coefficient in Eq. (5) to obtain the governing equation for the free vibration of the nonlinear MNBS embedded in the elastic medium.

Figure 11 shows the influence of the stiffness coefficient of the elastic medium on the nonlinear amplitude–frequency response curve of MNBS consisting of one-, three- and five-coupled nanobeams. It can be observed that an increase in the stiffness coefficient tends to decrease nonlinear effects visible on amplitude–frequency response curves, while these effects almost vanish for the highest values of stiffness coefficient. Moreover, in the case of the larger stiffness of the elastic medium, nonlinear frequencies are approaching the linear ones. On the other hand, an increase in the number of nanobeams in MNBS leads to a decrease in overall stiffness and nonlinearity becomes more prominent.

The effects of the nonlocal parameter and a number of nanobeams on the nonlinear amplitude–frequency response curves for each case of nanobeams in the system are shown in Fig. 12. It can be noticed that for given amplitudes and for an increase in the nonlocal parameter, the frequency ratio increases but the frequency decreases. This fact leads to the conclusion that the nonlocal parameter softens the system, i.e. reduces the overall stiffness. Moreover, one can observe that the influence of nonlocal effects is larger for a higher number of nanobeams and larger vibration amplitudes.

Amplitude–frequency responses of present MNBS and Fu et al. [67] for \(\left( {e_0 a} \right) =1\) nm

6.4 Validation study

In this work, results are obtained for MNBS embedded in the viscoelastic medium and the authors did not find a similar mechanical model in the literature that can be used for the validation study. However, for the special case of MNBS, i.e. the case with a single nanobeam on elastic foundation, we use the paper by Fu et al. [67]. Figure 13 shows the nonlinear amplitude–frequency response of MNBS consisting of one, three and five nanobeams and the amplitude–frequency response of the system with a single nanobeam resting on the elastic foundation presented in Fu et al. [67]. It should be noted that our model of MNBS is coupled in clamped chain system, i.e. for the case of a single nanobeam it is coupled with the fixed base through the elastic medium on both sides. This leads to higher values of the overall stiffness and such system is more constrained than the model proposed by Fu et al. [67].

7 Scope and limitations of the presented model

The given nonlinear MNBS is based on the nonlocal Euler–Bernoulli beam model and von Karman nonlinear deformations and does not take into account shear deformations. However, in order to consider this effect, one should consider Timoshenko or higher-order shear deformation beam theories. From the literature [18], we can see that the effect of transverse shear deformation leads to lower vibration frequencies comparing to the case with Euler–Bernoulli beam. This effect is more prominent in higher vibration modes. Therefore, the consideration of transverse shear deformation leads to a decrease in stability of the presented system, i.e. it leads to widening of instability regions [72]. It should be noted that applied axial loads are smaller than the critical buckling load, and MNBS is not buckled. However, the nonlinear vibration behaviour of buckled MNBS is also a very important issue and should be studied in some future works.

The second limitation refers to the fact that presented MNBS model consider amplitudes of nanobeams that are bounded by the surrounding viscoelastic medium. Based on that, we analysed only small nonlinear deformations by using the von Karman theory. It should be emphasized that we employed the phenomenological viscoelastic model based on simple mechanical analogy to describe the rheological behaviour of the viscoelastic medium in MNBS. Since the applied force–displacement relation is a phenomenological model of Kelvin–Voight’s viscoelastic stress–strain constitutive relation and reaction force of viscoelastic medium is distributed over nanobeam’s length, it can be represented by parallelly connected springs and dashpots with corresponding elasticity and viscosity coefficients. An interested reader can find more on experimental works and dynamic behaviour of CNT/polymer nanocomposites in [51,52,53, 75].

In the literature, the authors have found a series of papers [61, 67, 73, 74] where linear mode shape functions are used for a nonlinear vibration analysis of classical and scale-dependent beam models. However, we should mention two interesting papers by El-Borgi et al. [73] and Nayfeh and Lacarbonara [74], where the authors concluded that the Galerkin single-mode method is suitable for the discretization of governing equations of nonlinear vibration of simply supported beams, especially for the primary resonance state and the first vibration mode. According to this, the authors of the present paper employed only a single-mode Galerkin method for discretization of the governing equations of given MNBS. One should know that each nanobeam in MNBS has the same simply supported boundary conditions and therefore, same linear mode shape functions are considered in the assumed solutions of the system of governing equations. Moreover, in the absence of internal resonances, the steady-state response contains only the directly excited modes. The mathematical model of MNBS with considered interactions between modes, internal and combined resonances, is interesting to be analysed in some future study.

8 Conclusions

The present analysis describes the dynamic stability problem of the nonlinear MNBS embedded in a viscoelastic medium, where each nanobeam in the system is simply supported and subjected to axial time-dependent loads. A mathematical model of the nonlinear MNBS is based on the system of nonlinear partial differential equations of motion derived by using the Eringen’s nonlocal elasticity theory, Euler–Bernoulli’s beam theory and nonlinear von Karman strain–displacement relation. By employing the Galerkin discretization technique and IHB method, we determined the stability boundaries and periodic solutions of the system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations. For such determined periodic solutions, we introduced a Floquet theory to analyse their stability. In the numerical study, we have shown the influence of different material and geometric parameters on the stability behaviour of the presented nonlinear MNBS. A few novelties are proposed in this paper:

-

The Floquet multipliers are obtained as functions of different parameters of the stiffness coefficient, amplitude of the axial load and number of nanobeams.

-

The stability boundaries are obtained for different configurations of the nonlinear MNBS.

-

Coupled influence of nonlocal and nonlinear effect in the context of the stability behaviour of the nonlinear MNBS.

-

Semi-analytical periodic solutions are obtained for nonlinear MNBS by using the IHB method, without introducing small parameter.

It can be concluded that the analysis of periodic solutions of the nonlinear MNBS without taking into account nonlocal effects might lead to large errors when investigating the dynamic behaviour of such complex systems. It is well known that a very small variation in amplitudes of axial loads can cause structural collapse and the values of amplitudes should be chosen carefully. Information based on reliable models are important for the design of future nanostructure-based devices; therefore, this study besides theoretical could also have practical applications in nanoengineering fields. In addition, this study might be important for future theoretical analyses of the nonlinear dynamic behaviour of MNBS such as internal resonance, combined resonance conditions, and chaos.

References

Pourkiaee, S.M., Khadem, S.E., Shahgholi, M., Bab, S.: Nonlinear modal interactions and bifurcations of a piezoelectric nanoresonator with three-to-one internal resonances incorporating surface effects and van der Waals dissipation forces. Nonlinear Dynam. 3(88), 1785–1816 (2017)

Pourkiaee, S.M., Khadem, S.E., Shahgholi, M.: Parametric resonances of an electrically actuated piezoelectric nanobeam resonator considering surface effects and intermolecular interactions. Nonlinear Dyn. 4(84), 1943–1960 (2016)

Wang, Y., Li, F.M., Wang, Y.Z.: Nonlocal effect on the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of buckled parametric double-layered nanoplates. Nonlinear Dyn. 85(3), 1719–1733 (2016)

Ghayesh, M.H., Amabili, M., Farokhi, H.: Nonlinear forced vibrations of a microbeam based on the strain gradient elasticity theory. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 63, 52–60 (2013)

Belardinelli, P., Ghatkesar, M.K., Staufer, U., Alijani, F.: Linear and non-linear vibrations of fluid-filled hollow microcantilevers interacting with small particles. Int. J. Nonlinear Mech. 93, 30–40 (2017)

Hinds, B.J., Chopra, N., Rantell, T., Andrews, R., Gavalas, V., Bachas, L.G.: Aligned multiwalled carbon nanotube membranes. Science 303(5654), 62–65 (2004)

Kang, S.J., Kocabas, C., Ozel, T., Shim, M., Pimparkar, N., Alam, M.A., Rotkin, S.V., Rogers, J.A.: High-performance electronics using dense, perfectly aligned arrays of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nature Nanotechnol. 2(4), 230 (2007)

Wang, S., Liang, R., Wang, B., Zhang, C.: Load-transfer in functionalized carbon nanotubes/polymer composites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 457(4), 371–375 (2008)

Kacem, N., Arcamone, J., Perez-Murano, F., Hentz, S.: Dynamic range enhancement of nonlinear nanomechanical resonant cantilevers for highly sensitive NEMS gas/mass sensor applications. J. Micromech. Microeng. 20(4), 045023 (2010)

Eringen, A.C.: On differential equations of nonlocal elasticity and solutions of screw dislocation and surface waves. J. Appl. Phys. 54(9), 4703–4710 (1983)

Eringen, A.C.: Nonlocal Continuum Field Theories. Springer, Berlin (2002)

Peddieson, J., Buchanan, G.R., McNitt, R.P.: Application of nonlocal continuum models to nanotechnology. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 41(3), 305–312 (2003)

Reddy, J.N.: Nonlocal theories for bending, buckling and vibration of beams. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 45(2), 288–307 (2007)

Reddy, J.N.: Nonlocal nonlinear formulations for bending of classical and shear deformation theories of beams and plates. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 48(11), 1507–1518 (2010)

Reddy, J.N., El-Borgi, S.: Eringen’s nonlocal theories of beams accounting for moderate rotations. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 82, 159–177 (2014)

Thai, H.T.: A nonlocal beam theory for bending, buckling, and vibration of nanobeams. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 52, 56–64 (2012)

Aydogdu, M.: A general nonlocal beam theory: its application to nanobeam bending, buckling and vibration. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 41(9), 1651–1655 (2009)

Ansari, R., Gholami, R., Rouhi, H.: Vibration analysis of single-walled carbon nanotubes using different gradient elasticity theories. Compos. Part B Eng. 43(8), 2985–2989 (2012)

Ansari, R., Sahmani, S.: Small scale effect on vibrational response of single-walled carbon nanotubes with different boundary conditions based on nonlocal beam models. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 17(4), 1965–1979 (2012)

Murmu, T., Adhikari, S.: Nonlocal transverse vibration of double-nanobeam-systems. J. Appl. Phys. 108(8), 083514 (2010)

Murmu, T., Adhikari, S.: Nonlocal effects in the longitudinal vibration of double-nanorod systems. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 43(1), 415–422 (2010)

Murmu, T., Sienz, J., Adhikari, S., Arnold, C.: Nonlocal buckling of double-nanoplate-systems under biaxial compression. Compos. Part B Eng. 44(1), 84–94 (2013)

Murmu, T., Adhikari, S.: Axial instability of double-nanobeam-systems. Phys. Lett. A 375(3), 601–608 (2011)

He, X.Q., Kitipornchai, S., Liew, K.M.: Resonance analysis of multi-layered graphene sheets used as nanoscale resonators. Nanotechnology 16(10), 2086 (2005)

Liew, K.M., He, X.Q., Kitipornchai, S.: Predicting nanovibration of multi-layered graphene sheets embedded in an elastic matrix. Acta Mater. 54(16), 4229–4236 (2006)

Rašković, D.: On some characteristics of the frequency equation of torsional vibrations of light shafts with several disks. Publ. l’Inst. Math. 5(11), 155–164 (1953)

Hedrih, K.S.: Dynamics of coupled systems. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2(2), 310–334 (2008)

Karličić, D., Murmu, T., Adhikari, S., McCarthy, M.: Non-local Structural Mechanics. Wiley, London (2015)

Li, X.F., Tang, G.J., Shen, Z.B., Lee, K.Y.: Size-dependent resonance frequencies of longitudinal vibration of a nonlocal Love nanobar with a tip nanoparticle. Math. Mech. Solids 226, 1529 (2016)

Kiani, K.: Nonlocal discrete and continuous modeling of free vibration of stocky ensembles of vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes. Curr. Appl. Phys. 14(8), 1116–1139 (2014)

Kiani, K.: Nonlinear vibrations of a single-walled carbon nanotube for delivering of nanoparticles. Nonlinear Dyn. 76(4), 1885–1903 (2014)

Kiani, K.: Longitudinally varying magnetic field influenced transverse vibration of embedded double-walled carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 87, 179–199 (2014)

Mohammadi, M., Ghayour, M., Farajpour, A.: Free transverse vibration analysis of circular and annular graphene sheets with various boundary conditions using the nonlocal continuum plate model. Compos. Part B Eng. 45(1), 32–42 (2013)

Hu, Y.G., Liew, K.M., Wang, Q., He, X.Q., Yakobson, B.I.: Nonlocal shell model for elastic wave propagation in single-and double-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 56(12), 3475–3485 (2008)

Şimşek, M.: Vibration analysis of a single-walled carbon nanotube under action of a moving harmonic load based on nonlocal elasticity theory. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 43(1), 182–191 (2010)

Karaoglu, P., Aydogdu, M.: On the forced vibration of carbon nanotubes via a non-local Euler–Bernoulli beam model. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 224(2), 497–503 (2010)

Ansari, R., Mohammadi, V., Shojaei, M.F., Gholami, R., Sahmani, S.: On the forced vibration analysis of Timoshenko nanobeams based on the surface stress elasticity theory. Compos. Part B Eng. 60, 158–166 (2014)

Ansari, R., Ramezannezhad, H., Gholami, R.: Nonlocal beam theory for nonlinear vibrations of embedded multiwalled carbon nanotubes in thermal environment. Nonlinear Dyn. 67(3), 2241–2254 (2012)

Kiani, K.: Wave characteristics in aligned forests of single-walled carbon nanotubes using nonlocal discrete and continuous theories. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 90, 278–309 (2015)

Kiani, K.: Nonlocal continuous models for forced vibration analysis of two-and three-dimensional ensembles of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 60, 229–245 (2014)

Kiani, K.: In-and out-of-plane dynamic flexural behaviours of two-dimensional ensembles of vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. B Condens. Matter 449, 164–180 (2014)

Kiani, K.: Free vibration of in-plane-aligned membranes of single-walled carbon nanotubes in the presence of in-plane-unidirectional magnetic fields. J. Vib. Control 22(17), 3736–3766 (2016)

Kiani, K.: Forced vibrations of a current-carrying nanowire in a longitudinal magnetic field accounting for both surface energy and size effects. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 63, 27–35 (2014)

Kiani, K.: Application of nonlocal beam models to double-walled carbon nanotubes under a moving nanoparticle. Part I: theoretical formulations. Acta Mech. 216(1), 165–195 (2011)

Kiani, K.: Application of nonlocal beam models to double-walled carbon nanotubes under a moving nanoparticle. Part II: parametric study. Acta Mech. 216(1), 197–206 (2011)

Arani, A.G., Kolahchi, R., Zarei, M.S.: Visco-surface-nonlocal piezoelasticity effects on nonlinear dynamic stability of graphene sheets integrated with ZnO sensors and actuators using refined zigzag theory. Compos. Struct. 132, 506–526 (2015)

Wang, Y., Li, F.M., Wang, Y.Z.: Nonlocal effect on the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of buckled parametric double-layered nanoplates. Nonlinear Dyn. 85(3), 1719–1733 (2016)

Wang, Y., Li, F.M., Wang, Y.Z.: Homoclinic behaviours and chaotic motions of double layered viscoelastic nanoplates based on nonlocal theory and extended Melnikov method. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary. J. Nonlinear Sci. 25(6), 063108 (2015)

Pavlović, I.R., Karličić, D., Pavlović, R., Janevski, G., Ćirić, I.: Stochastic stability of multi-nanobeam systems. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 109, 88–105 (2016)

Bolotin, V.V.: The Dynamic Stability of Elastic Systems (translated from Russian). Holden-Day, San Francisco (1964)

Suhr, J., Koratkar, N., Keblinski, P., Ajayan, P.: Viscoelasticity in carbon nanotube composites. Nature Mater. 4(2), 134–137 (2005)

Moniruzzaman, M., Winey, K.I.: Polymer nanocomposites containing carbon nanotubes. Macromolecules 39(16), 5194–5205 (2006)

Ahir, S.V., Huang, Y.Y., Terentjev, E.M.: Polymers with aligned carbon nanotubes: active composite materials. Polymer 49(18), 3841–3854 (2008)

Atanackovic, T.M., Pilipovic, S., Stankovic, B., Zorica, D.: Fractional Calculus with Applications in Mechanics: Vibrations and Diffusion Processes. Wiley, London (2014)

Lu, J.P.: Elastic properties of carbon nanotubes and nanoropes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79(7), 1297 (1997)

Sudak, L.J.: Column buckling of multiwalled carbon nanotubes using nonlocal continuum mechanics. J. Appl. Phys. 94(11), 7281–7287 (2003)

Zhang, Y.Q., Liu, G.R., Xie, X.Y.: Free transverse vibrations of double-walled carbon nanotubes using a theory of nonlocal elasticity. Phys. Rev. B 71(19), 195404 (2005)

Sears, A., Batra, R.C.: Macroscopic properties of carbon nanotubes from molecular-mechanics simulations. Phys. Rev. B 69(23), 235406 (2004)

Ansari, R., Rouhi, H., Sahmani, S.: Calibration of the analytical nonlocal shell model for vibrations of double-walled carbon nanotubes with arbitrary boundary conditions using molecular dynamics. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 53(9), 786–792 (2011)

Ansari, R., Ajori, S., Arash, B.: Vibrations of single-and double-walled carbon nanotubes with layerwise boundary conditions: a molecular dynamics study. Curr. Appl. Phys. 12(3), 707–711 (2012)

Lau, S.L., Cheung, Y.K., Wu, S.Y.: A variable parameter incrementation method for dynamic instability of linear and nonlinear elastic systems. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 49(4), 849–853 (1982)

Cheung, Y.K., Lau, S.L.: Incremental harmonic balance method with multiple time scales for aperiodic vibration of nonlinear systems. J. Appl. Mech. 50, 871–876 (1983)

Shen, Y.J., Wen, S.F., Li, X.H., Yang, S.P., Xing, H.J.: Dynamic analysis of fractional-order nonlinear oscillator by incremental harmonic balance method. Nonlinear Dyn. 85(3), 1457–1467 (2016)

Sze, K.Y., Chen, S.H., Huang, J.L.: The incremental harmonic balance method for nonlinear vibration of axially moving beams. J. Sound Vib. 281(3), 611–626 (2005)

Yuanping, L., Siyu, C.: Periodic solution and bifurcation of a suspension vibration system by incremental harmonic balance and continuation method. Nonlinear Dyn. 83(1–2), 941–950 (2016)

Azizi, Y., Bajaj, A.K., Davies, P., Sundaram, V.: Prediction and verification of the periodic response of a single-degree-of-freedom foam-mass system by using incremental harmonic balance. Nonlinear Dyn. 82(4), 1933–1951 (2015)

Fu, Y.M., Hong, J.W., Wang, X.Q.: Analysis of nonlinear vibration for embedded carbon nanotubes. J. Sound Vib. 296(4), 746–756 (2006)

Simić, S.: Analytical Mechanics: Dynamics, Stability, Bifurcation. FTN Novi Sad, Serbia (2009)

Hsu, C.S.: On approximating a general linear periodic system. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 45(1), 234–251 (1974)

Friedmann, P., Hammond, C.E., Woo, T.H.: Efficient numerical treatment of periodic systems with application to stability problems. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 11(7), 1117–1136 (1977)

Shen, J.H., Lin, K.C., Chen, S.H., Sze, K.Y.: Bifurcation and route-to-chaos analyses for Mathieu–Duffing oscillator by the incremental harmonic balance method. Nonlinear Dyn. 52(4), 403–414 (2008)

Hagedorn, P., Koval, L.R.: On the parametric stability of a Timoshenko beam subjected to a periodic axial load. Arch. Appl. Mech. 40(3), 211–220 (1971)

El-Borgi, S., Fernandes, R., Reddy, J.N.: Non-local free and forced vibrations of graded nanobeams resting on a non-linear elastic foundation. Int. J. Nonlinear Mech. 77, 348–363 (2015)

Nayfeh, A.H., Lacarbonara, W.: On the discretization of distributed-parameter systems with quadratic and cubic nonlinearities. Nonlinear Dyn. 13(3), 203–220 (1997)

Lu, H., Huang, G., Wang, B., Mamedov, A., Gupta, S.: Characterization of the linear viscoelastic behaviour of single-wall carbon nanotube/polyelectrolyte multilayer nanocomposite film using nanoindentation. Thin Solid Films 500(1), 197–202 (2006)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the project of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia under the Grant No. OI 174001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karličić, D., Cajić, M. & Adhikari, S. Dynamic stability of a nonlinear multiple-nanobeam system. Nonlinear Dyn 93, 1495–1517 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-018-4273-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-018-4273-3