Abstract

The study of flood risk perception factors can be considered by using different paradigms. In an attempt to understand risk perception, two basic paradigms can be distinguished: rationalist and constructivist. The rationalist approach tends to focus on modeling, characterizing, and predicting behavioral results regarding various threats. According to the constructivist paradigm, threats are perceived as socially constructed. This review paper aims to assess the importance of the rationalist and constructivist approaches in research on flood risk perception and flood risk management more broadly by answering the questions: (1) Which paradigm dominates the research of flood risk perception?, (2) What is the relationship between rationalistic and constructivistic factors (e.g., stimulation, weakening, strengthening, etc.)?, (3) which factors are more effective in moderating attitudes toward flood risk? The paper concludes by pointing out the desired direction of research on flood risk perception from the perspective of improving flood risk management. In contemporary empirical works managing the perception of flood risk, a rationalistic approach that psychometrically searches for cognitive models dominates. Often, statistically obtained dependencies are mutually exclusive. Studies on perception that apply the constructivist approach are in an early stage of development, nevertheless providing consistent results. They indicate that the social, political, cultural, religious, and historical contexts shape the perception of flood risk. On the basis of the aforementioned information, research on flood risk in a constructivist approach should be expanded, as it provides a clear, often underappreciated catalog of contextual factors shaping risk perception and, importantly, simultaneously moderating the influence of rationalist factors on flood risk perception.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Traditional approaches to flood risk management (FRM) that focus on physical flood protection or improvements in flood monitoring and forecasting have tended to overlook the social dimensions of floods, such as the public’s understanding of risk. Risk perception, which involves assessing the public's perceived probability of a hazards and the probability of consequences (most often—negative consequences) (Bubeck et al. 2012, Becker et al. 2013, Grothmann and Reusswig 2006), is often equated with the awareness of the existence of a hazard and the resulting worry (Lechowska 2018).

Risk perception is a key social component in flood risk management (Bradford et al. 2012). Today, flood perception is recognized as a key factor in developing effective flood management strategies. How people perceive and understand flood risk affects the actions they take to prepare for and respond to flood events (Bradford et al. 2012). Therefore, in order to assess the usefulness of the applied research approaches for improving FRM, the study also included empirical works that, with reference to the level of flood risk perception, look for determinants of risk attitudes. For as Raaijmakers et al. (2008) flood risk perception can be considered as the relationship between the three specific risk characteristics: awareness, worry, and preparedness.

The issue addressed in this paper is all the more important because of the contemporary phenomenon of flood risk underestimation, which poses an important challenge for flood risk management. In order to improve FRM, it seems necessary to indicate the direction of research on flood risk perception, the results of which will be used for conscious and controlled moderation of perception and attitude toward flood risk, in effect developing a risk communication strategy to increase the resilience of the population to flood risks.

Motivated by many goals, orientations, and research interests, the studies of flood risk perception have presented a heterogeneous picture. Perception research has been conducted by researchers from various fields of science, resulting in a discrepancy in the basic theoretical issues (even the definition of risk), a different way of formulating a research problem, and the diversity of applied methods.

Bubeck et al. (2012) and Kellens et al. (2013) have stated, based on a literature review on the perception of flood risk, that there is no basic theoretical framework available within the social sciences. This work aims to fill this gap and strengthen the theoretical basis of the research on the perception of flood risk distinguishing on the grounds of epistemology two basic paradigms—rationalist and constructivist—similar to Brikholz et al. (2014). However, these paradigms are not dichotomous (absolute). Their distinction is aimed at highlighting heterogeneity in the field of flood risk perception research—discrepancies in applied approaches. The terms rationalist and constructivist have epistemic connotations, which cannot be simply characterized by methodological approaches that would be strictly pertinent to one or the other epistemology.

This paper aims to answer the main research question: research in which approach provides more useful information to improve flood risk management. Three specific questions were raised to meet the research objective:

-

Which paradigm dominates the research of flood risk perception?

-

What is the relationship between rationalistic and constructivistic factors (e.g., stimulation, weakening, strengthening, etc.)?

-

Which factors are more effective in moderating attitudes toward flood risk?

The relevance of rationalist and constructivist approaches in the study of flood risk perception and flood risk management more broadly was assessed through:

-

Explore, how the substantive scope of research on flood risk perception factors in the context of applied paradigms has evolved by proposing the categorization of the studied factors according to their character and applied research approach;

-

Determining the interrelationships between the various factors of a rationalist and constructivist nature (and between the paradigms more broadly) by comparing the results of research conducted in the two distinguished research streams;

-

Determining the role of rationalist and constructivist factors in shaping flood risk perception and attitudes toward flood risk.

The culmination of the purpose of this paper is to indicate the desired direction of flood risk perception research from the perspective of improving flood risk management.

An analysis of the results of the two strands of research will make it possible to identify factors of a rationalist and constructivist nature that unambiguously determine and undetermine the perception of flood risk and hence the attitude toward risk, as well as those with an ambiguous influence. For flood risk management the most important studies are those that give unambiguous results of the influence of a given factor on the phenomenon under study. Thus, those with inconsistent influence were considered effective factors for moderating perception and attitude toward flood risk. To strengthen their role in improving FRM, the possibility of their control by decision makers was also taken into account. Importantly, additionally, a cross-comparison of the results of studies conducted in these two paradigms provides information about the interplay of the influence of rationalist and constructivist factors.

Many studies have listed the factors that may influence flood risk assessment, but none considers the issue in the context of assessing the importance of rationalist and constructivist approaches to flood risk management. The work of Brikholz et al. (2014) refers to the aforementioned approaches but does not focus on the analysis of factors affecting flood risk assessment. This article therefore attempts to fill research gap in this area. Most of the reviews have focused on identifying predictors of adaptive behavior to mitigate flood risks (Bubeck et al. 2012, Koerth et al. 2017, Bamberg et al. 2017, van Valkengoed and Steg 2019, Kellens et al. 2013). Some have only considered one type of factor, e.g., flood experience, gender, education, and employment status as factors of flood risk perception understood as a combination of awareness, preparedness, and worry (Bradford et al. 2012), knowledge, trust, protection responsibility, physical exposure, hazard experience, and socio-demographics as variables affecting flood risk perception and preparedness—application of adaptive measures (Kellens et al. 2013), experience and trust in authorities and experts as factors influencing risk perception of natural hazards (including floods) and behavioral responses (Wachinger et al. 2013), or the spatial scope of the analyses is strictly defined, e.g., Central and Eastern European countries (Raška 2015). Few studies have compared the research results of risk perception in a transnational perspective (e.g., Boholm 1998).

The paper is divided into sections reflecting the logical sequence of the research. The introduction describes the significance of the issue being addressed and the purpose of the research. The second section is devoted to characterizing the rationalist and constructivist approaches. The next third presents the classifications of flood risk perception factors available in the literature. The fourth section describes the research method in detail, including the thought pattern and classifies the flood risk perception factors according to the research streams. The fifth part is devoted to the results of the research, more specifically, to presenting the evolution of the substantive scope of the factors of flood risk perception and to comparing the results of the research conducted in the two distinguished research streams. Conclusions and discussion answered the research questions, including identifying the interrelationships between the various rationalist and constructivist factors (and between paradigms more broadly), identifying the role of rationalist and constructivist factors in shaping attitudes toward flood risk, assessing the significance of rationalist and constructivist approaches in research on the perception of flood risk and more broadly in flood risk management. The paper concludes by indicating the desirable direction of flood risk perception research from the perspective of improving flood risk management.

2 Rationalist and constructivist paradigm

2.1 Rationalist paradigm

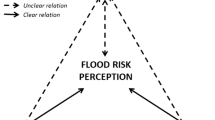

The rationalist approach to risk perception stresses individual cognitive processes and assumes that the existence of a threat induces an individual to make an assessment or judgment that feeds a "rational" decision-making process regarding the need to adopt a protective or preventive behavior (Birkholz et al. 2014). Studies rooted in the rationalist approach have tended to focus on modeling, characterizing, and predicting behavioral results regarding various threats. Such substantive approaches, for example, limited rationality and protection motivation theory, are largely rooted in the rationalist paradigm (closely related to cognitive psychology) and reveal the complex dependence of factors that can influence decision-making regarding protection against flood risk, including those that are contextual in nature (Birkholz et al. 2014) (Fig. 1). The rationalist paradigm assumes that individual risk preferences and behavioral results are the effects of a logical assessment of the likely outcomes, as well as related costs and benefits. Of interest is how individuals assess the costs and benefits of living in the affected areas (White 1945; Kates 1963; Burton et al. 1965).

In addition to cost–benefit evaluations conducted in the revealed preferences approach, another important approach in the rationalist paradigm is psychometric research (Birkholz et al. 2014) (Fig. 1). This theory has been introduced by Fischhoff et al. (1978) and Slovic (1987) and interprets risk as a cognitive construct that can be described psychometrically to reveal quantitative levels of evaluation (De Marchi 2007). The psychometric approach was initially developed by psychologists as a way of quantifying the individual perception of risk. It assumes that people interpret the world in terms of cause-and-effect patterns, and the existence of cognitive patterns allows modeling (by statistical methods) of a psychological phenomenon (Kellens et al. 2013). In psychometric studies, questionnaire surveys are the most often used source of data acquisition and help researchers search for cognitive variables that affect the perception of risk.

In the initial phase of psychometric research, researchers have focused on describing the qualitative characteristics of various types of risks (from environmental, through technological, to everyday risks such as communication), which were then replicated in different countries (Fischhoff et al. 1978; Slovic et al. 1980; Vlek Stallen 1981; Otway and Winterfeldt 1982; Englander et al. 1986; Teigen et al. 1988; Keown 1989; Goszczyńska et al. 1991; Karpowicz-Lazreg and Mullet 1993; Poumadere et al. 1995; Kleinhesselink and Rosa 1991, 1994). Later, the qualitative features of risk characterization were eliminated in favor of studying the relationship between risk perception and socio-demographic predictors such as gender, age, education, income, or social status (e.g., Flynn et al. 1994; Siegrist and Gutscher 2008; Lindell and Hwang 2008; Oasim et al. 2015). Additionally, the group of examined explanatory variables has been gradually extended by others, for example, in the field of exposure to risk or disaster experiences (Kellens et al. 2011; Barnett and Breakwell 2001; Baan and Klijn 2004; Knocke and Kolivras 2007; Werritty et al. 2007). Subsequently, as part of psychometric research, attention has been focused on the study of adaptive behavior toward risk—to search for predictors of desired attitudes (Miceli et al. 2008; Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Botzen et al. 2009a; b).

2.2 Constructivist paradigm

The constructivist paradigm largely rejects the idea that the assessment of threats is an objective phenomenon, independent of the social system. Under this approach, flood risk perception is perceived as socially constructed and closely related to the dynamics of changes in the social system, for example, values, beliefs, culture, institutions, and organizations (Drake 1992; Oliver-Smith 1996; Tierney 1999; Weichselgartner 2001; Johnson et al. 2004). The constructivist paradigm promotes the concept of risk as a contextual phenomenon (Birkholtz et al. 2014); it assumes that individual's judgments and decision-making processes are shaped and limited by social environments (Kates 1963; Drake 1992; Tierney 1999; Slovic 2000). The constructivist paradigm therefore recommends an analysis of how the sociocultural context shapes a broader understanding of risk; it draws attention to the mechanisms by which risk perception can be disseminated and legitimized at a broader social level (Tierney 1999). The constructivist paradigm provides insights into factors that drive, transform, and moderate the dynamics between risk perception and management, for example organizational, institutional, and social factors (Gustafson 1998). For example, Tierney (1999) provides a penetrating picture of how institutions dictate to the public the understanding of risk and how social inequalities combine with exposure to risk.

One important theoretical current associated with constructivist thinking is cultural theory, which assumes that the perception and acceptance of risk are rooted in social and cultural norms (Shaw et al. 2004) (Fig. 1). Proponents of cultural theory suggest that it is possible to determine the probable perception of risk derived from cultural affiliation and social understanding. In this theory, attention is paid to how the structures of a social organization convey and strengthen the perception of risk by an individual (Douglas and Wildavsky 1982). The concept of risk in society according to the cultural theory is considered in a broader perspective, embracing moral values and considerations, as well as political, social, and ideological issues (see Douglas and Wildavsky 1982; Rayner and Cantor 1987; Thompson et al. 1990; Wildavsky and Dake 1990; Dake 1991; Douglas 1992). For example, Douglas and Wildavsky (1982) link four "worldview(s)" (individualistic, egalitarian, hierarchical, and fatalistic) with some attitudes toward risk. These "worldview(s)" proposed by Douglas (1978) are the expression of the application of cultural theory in risk perception studies because they reflect the combination of "cultural prejudices" (common values and beliefs) and "social relations" (models of interpersonal relations).

Two groups of sociological theories can be distinguished that fit into the research on attitudes to risk carried out in the constructivist paradigm: focusing on the interplay of society and individual practices (practice theories) and network theories (Fig. 1). According to the former, an individual's behavior is always embedded in social structures and the power relations associated with them. This behavior is modified in everyday social interactions and practices (Bourdieu 2010; Giddens 1979; Reckwitz 2002, Ober and Sakdapolrak 2017). Network theories focus on social capital understood as "features of social organization, such as trust, norms and networks that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions" (Putman 1993, p. 167). These are theories with an emphasis on collective behavior. They include the social identity model of collective action (SIMCA) and social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). SIMCA examines the impact of group efficacy beliefs in bringing about change and group-related anger on motivating people to band together to improve the group as a whole Van Zomeren et al. 2008. SIMPEA shows how social identity processes influence judgment and behavior in the face of large-scale environmental crises. Social identity is the human ability to define oneself in terms of “We” rather than “I,” enabling people to think and act as a collective, which should be crucial given personal inadequacy in assessing and responding effectively to environmental crises (Fritsche et al. 2018).

The line of research conducted in both the rationalist and constructivist paradigms is "heuristics." In studies of flood risk perception, the heuristic of accessibility and the heuristic of affect have been considered the most (Fig. 1). The first one refers to what people remember and not what actually occurred (Lichtenstein et al. 1978). It is posited that people in conditions of uncertainty are guided by certain mental models that reflect the human thought process and refer to an individual’s assessment of the situation (Birkholtz et al. 2014). For example, threats that are more dramatic and spectacular can be more easily remembered, and their higher cognitive "availability" can explain the tendency among respondents to overestimate the risk of such threats (Lichtenstein et al. 1978). Papers in cognitive psychology have indicated that cognitive models and mental mechanisms of risk assessment are constantly moderated (modified, strengthened, or weakened) by media reports and influenced by friends, family, and various communication processes (Morgan et al. 2001). Research on risk perception (e.g., environmental, technological, road, and aviation hazards) has demonstrated the media's influence on the ease of recalling threats, resulting in an overstated risk assessment (Johnson and Tversky 1983). Additionally, Boholm (1998) emphasized that if the heuristic of accessibility is to be taken seriously as a theoretical framework for understanding risk perception, attention should be paid to how threats are represented socially, for example, in the media. The heuristic of affect thus says that mental representations are "marked" by weak negative or positive feelings. Finucane et al. (2000) showed that the perception of risk is an "affect marker"; namely, risk assessment often occurs under the influence of emotions. Siegrist and Gutscher (2008), Miceli et al. (2008), and Terpstra (2011) have also pointed out the importance of affect in perceiving and communicating the risk of flooding.

3 Classifications of flood risk perception factors in the literature

Many classifications of factors have been presented in the literature according to their nature (Table 1). Tobin and Montz (1997) distinguish situational and cognitive factors, and Wachinger et al. (2013) identify informational, personal, and contextual agents. Contextual factors have also been observed in Boholm (1998) and Brikholz et al. (2014). O’Neill et al. (2016) focus on cognitive (behavioral), socioeconomic, and geographical factors. A reasonably up-to-date classification of flood risk perception agents is in Lechowska (2018), in which six groups of factors (cognitive, behavioral, socioeconomic, demographic, geographical [physics], and informational and contextual) were identified. The featured classifications are inconsistent; they are developed at different levels of detail and present different perspectives on the interpretation of the nature of flood risk perception factors. Additionally, they are divided based on diverse criteria for the division. However, none of them considers the application of rationalist or constructivist paradigm. Therefore, it seems worthwhile to categorize the factors used in the research, based on approaches presented in the introduction of this paper, which was done in Sect. 4.3.

4 Research design

4.1 Methods

To achieve the goals set in the introduction, a research procedure was conducted comprising stages shown in Fig. 2.

The empirical works devoted to flood risk assessment research published in 1998–2018 to capture contemporary trends in research in this area were selected in the following manner: (a) the empirical works were selected from Google Scholar, the Web of Science/Knowledge, and Scopus databases meeting the following input criteria: full-text available/accessible, language used: English language, journals: papers published in peer-reviewed journals, by using a keyword combination, namely flood, factors, risk perception, flood risk, preparedness, worry, awareness, threat, risk underestimation, and denial; (b) in the selected articles, the following sections were reviewed in the following order—abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion—(c) which allowed for the development of an initial list of factors that may affect the perception of flood risk and attitudes toward risk; (d) if the aforementioned parts of the article focused on the aforementioned subject matter, this article was subject to a deeper review (i.e., entire text); and (e) further selection of research was made using the "snowballing" strategy (works cited in papers selected first according to steps b-d in three iterations were analyzed). As a result, the review includes 48 empirical works that focus on determining the level of perception of flood risk and identifying its possible factors. The catalog of variables adopted in the analyzed studies results from either the purpose of the research or an earlier literature review conducted by the authors of the analyzed works. The analyzed studies are "a sample" of all published empirical studies in analyzed period of time, which to some extent limits the inference. The paper provides a generalized view of the main linkages and relationships identified in the literature. Nonetheless, the results of the review provide useful insights about the findings of flood risk perception studies, capture some trends and regularities, and suggest possible directions for future research.

In the second stage, a categorization was conducted of the factors examined based on how they were applied in particular research approaches (rationalist and constructivist). The nature of the factor resulted from the research paradigm used in the study.

To determine the dynamics of changes in the substantive scope of research on flood risk perception factors, the changes in dynamics of occurrence frequency of the given groups of flood risk perception factors were analyzed in the third stage. For this purpose, a frequency ratio was used, which expresses the percentage share of consideration of a given factor in the total number of considerations of all factors in research articles in the year studied. This analysis helps to indicate, which paradigm dominates the research of flood risk perception.

RF—frequency ratio.x1—consideration of a given factor.xn—the total number of considerations of all factors in research articles in the year.

In the next stage, the comparison of results based on the adopted research approach was prepared to assess whether the test results of a given approach were unambiguous or mutually exclusive. Contradictory research results indicate their low applicability in flood risk management, as it is not possible to effectively moderate people's attitudes toward flood risk based on uncertain, often contradictory findings. Unambiguous research results are more useful and effective in this regard—they clearly identify the factors that shape flood risk perception.

As already mentioned, the distinction between rationalistic and constructivistic paradigms is not dichotomous. Research conducted in these paradigms can overlap, making it possible to determine the interrelationship between them by comparing the results of research conducted in a rationalistic and constructivistic approach.

The above-mentioned stages made it possible to achieve the main goals of the study. At the end, recommendations were formulated on what should be the direction of flood risk perception studies to improve flood risk management?

4.2 Categorization of flood risk perception factors based on the applied research approach

The flood risk factor perception was classified as rationalist or constructivist based on the method, in which the factor was included in the study, what role it played, and how it was interpreted by the particular researcher conducting the empirical study. Thus, the very way in which a particular researcher approached the research (formulating the research question) conditioned the categorization of factors, i.e., whether he or she viewed them as a cognitive variable, a predictor in modeling cognitive patterns, as an element of a cause–effect scheme of conduct in a "rational" decision process, or as a socially constructed element in a context’s meaning. However, the classes are not dichotomous, and some factors can be assigned to many categories (e.g., gender can be used as rationalist or be socially defined/constructed). For the purpose of this work, mixed factors were also assigned to one of the categories by considering how the factor is framed by the researcher himself.

As a result, the following classes of factors were included in the rationalist paradigm: individual’s physical location, flood characteristics, residence characteristics, size of consequences, range of impact, direct experience, socioeconomic and demographic profiles, and information (knowledge). Accordingly, to constructivist paradigm agents such as indirect experience, the cultural–historical, religious, and political contexts were assigned (Fig. 3).

5 Results

5.1 Evolution of substantive scope of research on flood risk perception factors

In the study group of empirical papers published between 1998 and 2018, the greatest interest in the study of factors shaping the perception of flood risk was in 2008 and 2009. These works are mostly from northern Europe (the Netherlands, Denmark, England) and Taiwan and to a lesser extent from Western Europe (France, Switzerland, Northern Italy). In 2011 and 2015, we observe more interest from researchers from Germany and Belgium and then from the Czech Republic and Romania. Toward the end of the time period analyzed, there is a decline in the interest of researchers in flood risk perception (Fig. 4).

The empirical studies analyzed discuss factors that may influence the perception of flood risk (Table 2). These studies are mostly from the rationalist perspective because they concern groups of variables such as an individual's physical location (flood hazard level—flood zone), flood characteristics, size of consequences (the amount of potential flood losses), range of impact (direct or indirect hazard depending on the application of flood protection measures), direct experience, socioeconomic and demographic profiles, and information (knowledge). The frequency ratio for considering the aforementioned factors in the analyzed papers is 85.5%. Other factors, such as the indirect experiences, cultural–historical contexts, and religious and political contexts expressed the constructivist paradigm, are to a lesser extent considered in studies of flood risk perception (the frequency ratio for their inclusion is 14.5% (Fig. 5).

The psychometric approach prevails in the collected research works in the rationalist paradigm. The authors of these papers are attempting to statistically describe the phenomenon in the area of social research. These papers present a quantitative analysis of individual risk perception, assuming the existence of cognitive patterns that allow the studied phenomena to be modeled (Fischhoff et al. 1978; De Marchi 2007; Kellens et al. 2013). Therefore, in the aforementioned papers, these factors appear mainly as independent variables included in the analyzing of the perception of flood risk.

In studies of the perception of flood risk conducted in the rationalist approach, the impact of direct flood experience on the level of risk perception is considered (the frequency ratio is 25.9%), followed by social, economic, and demographic factors (23.2%; Fig. 4). Other factors less frequently considered in the studies of flood risk perception are knowledge level (15.2%), residence characteristics (10.7%), and individual's physical location (10.7%). Other groups of factors, such as the size of consequences, flood characteristics, and the range of impact, are considered to a marginal extent (frequency ratio below 10.0%).

In the works conducted using the constructivist paradigm, the political context is most often considered (frequency ratio is 47.4%), followed by indirect experience (31.6%; Fig. 4). Cultural–historical and religious contexts are included to a lesser extent (frequency ratio of 15.8 and 5.3%, respectively).

Next, the development of researchers' interest in particular groups of factors that may influence the perception of flood risk is examined. At the beginning of the study period, the focus was on rationalistic factors. From 1998 to 2001, there was great interest in determining the influence of such factors as socioeconomic and demographic profiles, the range of impact and information (knowledge) on the level of flood risk perception. From 2002 to 2007, the focus is on direct experience and the related size of consequences, as well as residence characteristics. From 2008 to 2018, researchers focus on factors such as direct experience, socioeconomic and demographic profiles, information (knowledge), and residence characteristics, as well as an individual's physical location (Fig. 6).

Regarding constructivist factors (indirect experience and political, cultural–historical, and religious contexts), they began to be considered in empirical works on the perception of flood risk in 2009, later than the rationalist factors. From 1998 to 2003, research on the perception of flood risk primarily focuses on the religious context and interpersonal communication networks (shaping intermediate experience). From 2004 to 2012, the primary focus is political context and, from 2013 to 2018, the cultural and historical contexts (Fig. 6).

5.2 Impact of individual factors on the flood risk perception and attitude toward risk

Flood risk perception in empirical studies is expressed by worry and awareness and is often identified with it. A separate issue in the flood risk perception research is preparedness, defining attitude toward risk, and search for factors that would influence taking preventive measures in relation to the level of flood risk perception (Lechowska 2018). Therefore, the influence of factors on flood risk perception (including awareness and worry) and on attitudes toward risk is discussed separately.

5.2.1 Rationalist paradigm

The most attention is paid to factors that affect the perception of risk, followed by those factors that have no unequivocal influence on the studied phenomenon, and then the group of problematic factors (affecting perception).

Empirical research demonstrates that the transfer of information and the education of the public increase awareness (King 2000; Raaijmakers et al. 2008), similar to the experience of flooding (Lindell and Hwang 2008) and the very fact of the flood (Biernacki et al. 2009). Studies have also shown that people with a lower education are more worried about floods than those with a higher education are (Sjöberg 1998; Bradford et al. 2012). Bradford et al. (2012) assume that there is a relationship between education and income level and conclude that individuals with higher incomes are less worried about the consequences of flooding than those with lower incomes are (Fig. 7).

Empirical studies demonstrate the impact of knowledge on the perception of risk. People with little knowledge have a lower risk perception (Messner and Meyer 2006; Raaijmakers et al. 2008; Botzen et al. 2009a; Biernacki et al. 2009; Działek et al. 2013; Wachinger et al. 2013). Many studies have emphasized the significance of an individual’s experience in shaping the perception of flood risk (Barnett and Breakwell 2001; Slovic et al. 2004; Kreibich et al. 2005; Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Siegrist and Gutscher 2008; Zaalberg et al. 2009; Botzen et al. 2009a; Kellens et al. 2011; Duží et al. 2014; Bustillos Ardaya et al. 2017). People who have been directly affected by floods are characterized by a higher level of perception of flood risk (Kellens et al. 2011; Oasim et al. 2015; Thistlethwaite et al. 2018; Fig. 7).

Another factor that influences the perception of flood risk is gender. Kellens et al. (2011), Bustillos and Ardaya et al. (2017), and Lindell and Hwang (2008) has unequivocally indicated that women usually perceive a higher level of flood risk (Fig. 7).

In the research in the rationalist trend, researchers have demonstrated the influence of particular factors on the perception of flood risk but often excluded their impact, i.e., it shows the lack of effect of the variable on the phenomenon under study (Fig. 7).

Socioeconomic features such as income, age, gender, and education do not affect awareness. It has also been shown that neither income (Botzen et al. 2009a; Oasim et al. 2015) nor household size (Takao et al. 2004; Zaalberg et al. 2009; Oasim et al. 2015) have a significant impact on the perception of flood risk. Residence characteristics such as having a basement or living on the ground floor do not affect the level of perception of flood risk, as Kellens et al. (2011; Fig. 7) demonstrate.

A group of factors whose impact on the perception of flood risk is ambiguous is problematic. Bradford et al. (2012) do not show a strong relationship between anxiety and gender, whereas according to Sjöberg (1998) and Poorting et al. (2011) women more often show anxiety in response to perceived threats.

Kellens et al. (2011) show that older people usually assess the risk of flooding as higher than younger people, but according to Oasim et al. (2015) and Armas et al. (2015), age has no significant impact on the perception of flood risk. The level of education, according to Kellens et al. (2011) and Armas et al. (2015), is not decisive in risk perception; Oasim et al. (2015) and Botzen et al. (2009a) prove that the level of education increases the perception of flood risk (Fig. 8).

The analyzed literature suggests that real estate ownership is associated with a higher level of perception of flood risk than apartment rental (Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Burningham et al. 2008; Oasim et al. 2015), and Kellens et al. (2011) show no such a relationship (Fig. 8).

This discrepancy in the results also applies to the impact of the proximity of the hazard (river) on the level of perceived risk. According to some studies, the proximity of the source of hazard results in a higher perception of flood risk (Lindell and Hwang 2008; Miceli et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2010; O’Neill et al. 2016), and others posit that the closer the river, the lower the perception of risk, due to the incidental nature of flooding (Oasim et al. 2015; Colten and Sumpter 2009). Kellens et al. (2011) obtain no dependencies in this respect (Fig. 8).

The impact of the duration of residence on the perception of flood risk is also unclear. Thistlethwaite et al. (2018) demonstrate a moderate positive relationship, but Bustillos and Ardaya et al. (2017) demonstrate a very weak one (Fig. 8).

Concerning the factors that shape attitudes toward risk, the largest group are factors that have ambiguous effects on taking countermeasures. There is no match between the results of research on the impact of experience and knowledge (information) on the level of preparedness. Positive dependence between the experience of flood and the degree of involvement in the preparation of individual mitigation measures has been demonstrated by Takao et al. (2004), Slovic et al. (2004), Grothmann and Reusswig (2006), Siegrist and Gutscher (2008), Lamond et al. (2009), Biernacki et al. (2009), Terpstra (2011), Kreibich et al. (2011), Stojanow et al. (2015), and Thistlethwaite et al. (2018), and the correlation and regression values obtained have often been low or average (Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Thieken et al. 2007; Siegrist and Gutscher 2008; Lindell and Hwang 2008; Miceli et al. 2008). By contrast, Takao et al. (2004) and Thieken et al. (2007) and Duží et al. (2015) do not show such dependence. The level of knowledge of floods, according to Thieken et al. (2007), Miceli et al. (2008), weakly correlates positively with preventive actions, and Botzen et al. (2009a) show that the increase in knowledge of a threat reduces the willingness of the population to invest in protective measures; however, Siegrist and Gutscher (2008) show no such dependence (Fig. 8).

The results of the analyzed studies also ambiguously specify the relationship between the location in flood hazard zones and undertaking preventive actions. According to Duží et al. (2015), with an increase in hazard level, risk mitigation measures are more often used. Kunreuther (1996), by contrast, notes that people living in the most vulnerable areas rarely voluntarily take precautionary measures, increasing their vulnerability to disasters. In a study by Bera and Daněk (2018), the reluctance to subsidize in flood protection measures is higher the more threatened the village is (Fig. 8).

Age and income are the factors that have an ambiguous effect on readiness in the analyzed papers. According to some researchers, the age of inhabitants of flood zones has little or no significance in undertaking individual protective actions (Knocke and Kolivras 2007; Lindell and Hwang 2008; Zaalberg et al. 2009; Botzen et al. 2009a), while Działek et al., 2013), Grothmann and Reusswig (2006) show that older residents of these areas more often decide to use preventive measures. The significance of income for floodplain inhabitants taking preventive measures is low, according Lindell and Hwang (2008), Botzen et al. (2009a), and Zaalberg et al. (2009), but according to Grothmann and Reusswig (2006), Stojanow et al. (2015), and Thistlethwaite et al. (2018) more affluent residents are more willing to invest in flood mitigation measures (Fig. 8).

In contrast, a relationship is demonstrated between gender and having children and preparedness: men and households with children are more likely to take preventive measures (Stojanov et al. 2015; Fitton et al. 2015). In addition, Grothmann and Reusswig (2006), Harries and Penning-Rowsell (2011), and Thistlethwaite et al. (2018) have demonstrated a positive impact of owning a home on taking mitigation measures. For preventive behaviors, the type of building is also important. Applying security measures is much lower for multi-family buildings than for single-family buildings (Działek et al. 2013, 2014; Biernacki et al. 2009).

Many studies have also demonstrated very little or no effect of education on precaution (Sjöberg 1998; Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Lindell and Hwang 2008; Zaalberg et al. 2009; Botzen et al. 2009a). In addition, the distance from the threat (river) seems to have little effect on mitigating behaviors (Lindell and Hwang 2008; Miceli et al. 2008; Botzen et al. 2009a).

5.2.2 Constructivist paradigm

Research conducted using the constructivist approach indicates the great importance of cultural values, religion, political system, history, and types of social bonds in shaping the perception of flood risk (Fig. 9).

In studies that consider the social context, the impact of the communication network in the form of media (Biernacki et al. 2009) and personal interactions with other people on the assessment of flood risk are considered. Działek et al. (2013, 2014) demonstrate that the ability to obtain information and recall the experience depends largely on the type of social structures and social capital. In rural communities and small towns characterized by strong social bonds (bonding social capital), the importance of disseminating information on local hazards between generations by the inhabitants is observed. However, in the case of communities with weak social ties (bridging social capital), such as large cities, indirect experiences of residents are difficult to convey—populations are more mobile and personal interactions between people are limited (Działek et al. 2013, 2014; Cutter et al. 2003). According to Terpstra et al. (2009), other people's experiences and reports communicated through social communication—indirect experiences (e.g., the effects of floods experienced by friends, relatives, neighbors, and other people)—have a smaller impact on risk perception than personal, direct experience. Media coverage contributes to the perception of risk mainly when the recipient has no flood-related personal, direct experience (Wachinger et al. 2013), and according to Bustillos Ardaya et al. (2017), information provided at the local level (from neighbors, family, and friends) is more important in shaping risk perception than deliberate action by institutions through various information policies are.

Because few papers in the study group consider the social context in the research on risk perception, we refer to the results of the research with a more general character, namely those that refer to all hazards (technological, social, natural). Some results have demonstrated (e.g., Johnson and Tversky 1983; Short 1984) that media coverage may be biased, which strengthens the dramatism of catastrophic events while weakening the importance of everyday threats. Sjöberg et al. (1996) aptly note that the role of media in risk perception is complex and differs by society. For example, media in communist countries poorly inform residents about hazards and understate risk perception because they are more closely controlled by the government than in democratic states (Englander et al. 1986). Thus, the role of the next constructivist factor, namely the political and economic system that diversifies the role of the media in society, is emphasized.

In addition to what was aforementioned, the political context is considered by defining the role of public authorities in shaping the perception of flood risk, including defining the confidence in authorities and public flood protection measures and the associated sense of self-responsibility for risk mitigation activities. The conviction that the authorities bear the main responsibility for flood protection thus removes this burden from residents and is confirmed by Bichard and Kaźmierczak (2012) and by Terpstra and Gutteling (2008). As shown by Bera and Daněk (2018), reliance on public flood protection has resulted in not taking flood control measures. Similarly, Hung (2009) and Terpstra (2011) state that the confidence in public flood protection decreases with the increase in residents' preparedness and willingness to acquire insurance, and according to Bubeck et al. (2012), the actions of the authorities can be an obstacle to taking private mitigation measures. One such example is protection in the form of levees, which provides an apparent sense of security (the so-called levee effect) to the inhabitants of flood plains. This perception results in the underestimation of flood risk and inhibition of activities toward proper protection against floods (Burton and Cutter 2008; Terpstra 2009; Kousky and Kunreuther 2009; Ludy and Kondolf 2012). Notably, trust in the authorities becomes important in the case of low individual knowledge of the threat (Kellens et al. 2013; Wachinger et al. 2013). Trust in flood protection measures (the belief in their effectiveness) often results from previous flood experiences (Wachinger et al. 2013; Birkholtz et al. 2014).

The cultural context in the study of flood risk perception is considered by Armas et al. (2015), who conduct ethnographic research. Cultural conditions of the studied community constitute the background and complementation of the interpretation of the obtained psychometric results. With a small number of empirical studies on the cultural context published from 2008 to 2018, we must mention the earlier works on cultural values in risk assessment in relation to various types of threats. For example, Rohmann (1994) shows that risk assessments differ significantly in orientation (technological, monetary, environmental, and feminist). In other studies, the phenomena of “cross-cultural, cross-gender reversal” or the dependence of the impact of gender on the level of risk perception are considered. The assessment of risk perception of women in Japan and men in the United States was similar (Kleinhesselink and Rosa 1991). Gender as a variable plays a greater role in countries with more marked legal and cultural differences between the genders than those that do not. Also Gustafson (1998) with gender theory tried to explain the different perception of flood risk by men and women.

The historical element (apart from the direct experience of flooding) in contemporary studies of flood risk perception is explored in Działek et al. (2013, 2014), who underline the impact of the historical paths of the studied area on the strength of social bonds and type of social capital, and hence the indirect experience, on flood risk perception.

The problem of the influence of religion on the perception and attitudes toward flood risk was analyzed by Schmuck (2000) in the Muslim community, confirming the existence of this dependence in the studied group. In the analyzed community, the conviction that the flood is the work of Allah led to abandoning all actions aimed at the preparedness and mitigation of flood risks. Similarly, in Bustillos Ardaya et al. (2017), Brazilian respondents, when asked why private precautions were not taken, answered: "Whatever God's will is, it will happen," "whenever He wants to take me, it is because it is my time," or "it is not possible to know the intentions of the Lord." (p. 235). In this context, the importance of fatalism, wishful thinking, and hopelessness related to religion in shaping attitudes toward risk is observed. Fatalism and denial are among the non-protective reactions resulting from an inadequate assessment of handling the risk (e.g., response efficacy, self-efficacy, and response costs) with a simultaneous high-risk assessment. This approach to risk concerns people who, through their experience of flooding, are convinced of their inability to control such events. Fatalism, wishful thinking, and denial prevent only the negative emotional consequences of perceived risk, such as fear (Bustillos Ardaya et al. 2017). Notably, the religious and cultural context is also important in the selection of the studied characteristics of the population. For example, in the case of Muslim communities, women are excluded from the study (Oasim et al. 2015).

6 Discussion and conclusions

The abundance of research concerning the level of flood risk perception makes it a dynamic field of empirical research, the resources of which should interest decision makers managing flood risk. The empirical works analyzed provide a broad view of the applied research approaches.

Rationalists focus on the quantitative approach, probability, and consequences, and constructivists are more interested in the qualitative dimension. The constructivist approach may be criticized by researchers for its qualitative character and difficulty in operationalization (Oasim et al. 2014).

The topics and research interests concerning factors or groups of factors that may influence the perception of flood risk varied over time. In the beginning, attention was paid to the rationalistic approach (mainly to direct experience, socioeconomic and demographic profiles, and information, and later also to residence characteristics and individual's physical location). Over time, the amount of constructivist research increased, particularly that related to indirect experience and a political context. Research interests and their variations over time could result from the availability of data and development of research tools. For example, it is much easier to obtain (and measure) metric information on respondents (e.g., age, gender, education) than their more intimate (personal) data, such as religion and relationships with family or neighbors, and that on historical and cultural backgrounds. With the development of geographical information systems, the scope, detail, and availability of data increased, including techniques for delimiting flood zones, flood characteristics, identification of an individual's physical location, and residence characteristics.

The choice of factors for the perception of flood risk is often simply a matter of interest of an individual researcher. It may also be determined by the research results of other literature due to the easiness of the later discussion on the results obtained. This reasoning can sometimes become a mechanism of a "self-winding circle," resulting in the excessive expansion of one sphere of research at the expense of another.

Detailed conclusions of the review are presented in the form of answers to the research questions posed in the introduction.

6.1 Which paradigm dominates the research of flood risk perception?

Contemporary empirical works on flood risk perception are dominated by a rationalistic approach that psychometrically searches for cognitive patterns of behaviors when there is flood risk; however, research in the rationalist approach creates a heterogeneous field of research in terms of basic theoretical issues, methodology, and more importantly, the results obtained, as also highlighted in his review by Andráško (2021) in relation to the study of factors influencing attitudes toward risk in taking adaptive action. Often, statistically obtained dependencies are mutually exclusive. Physical, cognitive, behavioral, and demographic–economic variables alone cannot adequately explain attitudes toward flood risk. One limitation of some rationalistic studies is the "flattening" of variables or the inability to consider them because of external factors. For example, in the case of a location variable, there was a high degree of homogeneity (low variance), which resulted in lowering the importance of this variable in the results.

Thus, studies on flood risk perception in the constructivist approach are at an early stage of development. Currently, they are only a supplement to rationalistic research and not a mainstream tendency in the field of flood risk perception. However, studies of flood risk assessment by the public in a social, political, cultural, religious, or historical context provide a clear results.

6.2 What is the relationship between rationalistic and constructivistic factors (e.g., stimulation, weakening, strengthening, etc.)?

The analysis of the collected empirical works indicates mutual relations between individual factors of a rationalistic and constructivist nature. Andráško (2021) is of the opinion that the factors influencing risk attitudes are interrelated in some kind of complex relationship, but it is not entirely clear how the various elements interact, what is the nature of their (causal) connections, or what kinds of outcomes they produce.

This review has demonstrated that the influence of rationalistic factors on the level of flood risk perception often results from the constructivist context. For example, media coverage plays a greater role in shaping risk perceptions when the recipient does not have personal direct experience of flooding (Wachinger et al. 2013), and other people's experiences (e.g., the effects of the flood experienced by friends, relatives, neighbors, and other people) have a weaker impact on the perception of risk than personal direct experience (Terpstra et al. 2009). Trust in the authorities becomes more important when there is little individual knowledge of risk, and trust in flood protection measures (confidence in their effectiveness) often results from the previous experience of flooding. Furthermore, gender plays a greater role in shaping the perception of flood risk in countries where legal and cultural differences between the sexes are more outlined.

Constructivist research points to the moderating role of context in studies of flood risk perception. Constructivist factors weaken or strengthen the impact of rationalistic factors on the level of flood risk perception in general and attitude to risk. For example, negative feelings related to previous experiences decrease trust in authorities and official flood protection measures, while positive feelings increase trust. High trust public protection measures reinforce the influence of personal flood experience on risk perception and vice versa. Factors that modify the influence of knowledge on risk perception are communication networks in the form of media and personal interaction with other people (indirect experience) and the type of social capital and social ties, e.g., close social ties weaken the stimulating effect of knowledge on risk perception and vice versa. The policy of the authorities in providing public flood protection due to historical circumstances and the level of trust of the population in the authorities and in public protective measures moderates the relationship between risk perception and preparedness, e.g., the tradition of centralized policy in post-communist countries resulting in public reliance on public flood protection weakens the positive impact of risk perception on taking countermeasures. The relationship between perception and preparedness is also weakened by religion, e.g., in Muslim communities. Gender as a determinant variable of flood risk perception plays a greater role in countries with more pronounced legal and cultural gender differences ('cross-cultural, cross-gender reversal'). A constructivist approach to studying flood risk perception can deepen the understanding of the various, often antagonistic, results of rationalistic research.

Contemporary literature reviews are beginning to point out, that the influence of rationalistic factors on attitudes toward flood risk is driven by the influence of contextual factors. According to Andráško (2021), the roles assigned to individuals and social relationships/ ties/norms/structures are often the decisive factors behind differences in empirical findings. He identifies a discrepancy in results regarding the role of socio-demographic characteristics in shaping flood risk behavior in different situations across communities. In his view, socio-demographic characteristics do not act as direct predictors or determinants but should be seen as mediators or enhancers of the main links between experience, perception, and preparedness. Fox-Roger et al. (2016) consider emotions, which are the mechanism that directs basic psychological processes, and their associated feelings as elements that can explain the disconnect between consciousness and readiness.

6.3 Which factors are more effective in moderating attitudes toward flood risk?

As the influence of rationalistic factors on the level of flood risk perception often results from the constructivist context, knowing specific local political, cultural, historical, religious, and social conditions makes it possible to more effectively moderate the attitudes of the inhabitants toward flood risks.

It seems that some constructivist factors, such as the influence of media or neighbors, friends, and family on flood risk perception, are more controllable than rationalistic factors (e.g., direct experience of flooding, or gender or age). Decision makers tend to be more influential in controlling constructivist than rationalist factors. It seems that more control can be had over the former (soft—less tangible) than the latter (hard) factors. Constructive studies therefore provide more useful information for improving flood risk management.

Contemporary literature reviews point to similar findings. For example, Andráško (2021) noted that the strength and quality of social networks are important factors influencing the ability of communities to cope with flood risk, including social position (such as class), sociopolitical organization, poverty, social inequality, and environmental injustice. Andráško (2021) points out that the way local communities function, interpersonal ties and networks, mutual support and assistance, the behavior and example of neighbors and friends, possible deterioration of relationships related to perceived unfair distribution of financial compensation, rumors and feelings of jealousy or reproach, as well as trust in the effective functioning of risk management determines in some way people's preparedness for flood events. Additionally, according to Andráško (2021), affect heuristics appear to be an important determinant of how people prepare for and respond to risks. Another research review (Kuhlicke et al. 2020) notes that factors such as local discourses and narratives, (perceived) injustice and marginalization of certain actors or entire regions, and social ties may influence adaptive behavior in relation to flood events. According to Kuhlicke et al. (2020, p. 12) “capacities to take adaptive actions are enmeshed in specific contexts.”

Notably, the development of technology has changed the sources of information about threats, which should be reflected in the research on risk perception. The level of knowledge of risk should not be determined solely based on the knowledge of flood hazard maps, but also, and perhaps primarily, on the basis of media coverage. Empirical studies show that the media influence the perception of flood risk (inter alia Biernacki et al. 2009).

Therefore, in the practice of flood risk management, particular attention should be paid to the role of social media in shaping attitudes toward risk (com. Reutera et al. 2019; Yuan et al.. 2021; Kim and Madison 2020). More dramatic and catastrophic events are more frequently covered in the media than everyday hazards. This results in everyday hazards being perceived as less dangerous, less frightening, and easier to deal with, leading to an underestimation of the risks associated with more frequent events (Short 1984). As aptly noted by Boholm (1998), the availability heuristic should be taken seriously as a theoretical framework for understanding risk perception. Attention should be paid to how risks are represented socially, for example in the media. Brikholz et al. (2014) are also of the opinion that the media can play a key role in the social construction of risk perception. Andráško (2021) suggests that media analysis involves examining the way in which the disaster is portrayed in the media, how it is reported, and at the same time analyzes the emotional ruminations of the audience of these presentations. In the era of a digital society, electronic media might be more effective in communicating risk. Neighborly ties, by contrast, are loosening up and will be of minor importance in determining the role of indirect experience in shaping attitudes toward risk. It is worth noting the potential of using artificial intelligence (AI) to study the perception of flood risk based on social data. Since it is possible to profile people based on their social network entries, it is also possible to find some common characteristics for groups of people who are more resistant or vulnerable to flood risk based on such networks.

Moreover, within the group of constructivist factors, some relations can be observed. Information provided at the local level (from neighbors, family, and friends) is more important in developing the risk perception than the institutional impact is. The political and economic system makes the role of the media in society different. (Greater control of the authorities results in a more limited amount information on risks.) Different historical backgrounds influence the power of social bonds and the type of social capital, shaping the role of indirect experiences in flood risk perception.

6.4 Research in which approach provides more useful information to improve flood risk management?

Consequently, flood risk perception research conducted in a constructivist paradigm provides more useful information in shaping attitudes toward risk and finally provides more useful information to improve flood risk management.

7 Recommendation

The research on flood risk perception should be reoriented toward studying the role of contextual factors in shaping risk perception. It is necessary to assess how the public interprets flood risks socially and culturally, and not merely in terms of metric data. The study of risk perception is a social study because it concerns the observation and analysis of processes and phenomena occurring in society and uses information about the needs and opinions of the population and social practices. Thus, all the elements that determine the nature of the society under study (its world view, cultural history, social structures, norms, power relations, etc.) should be considered. According to ethnographers, human social existence is culturally variable. Perceptions of events and phenomena are conditioned by values that differ locally. Brikholz et al. (2014) express the same opinion and agree with the need to comprehensively reinvigorate flood risk research, supported by a more constructive approach to flood risk management. Tierney (1999) argues for the use of a constructivist approach by saying that it provides mechanisms by which specific risk perception can be disseminated and legitimized at a wider social level.

The results of this empirical study show a slow shift toward research on soft flood risk perception factors, conducted in the constructivist approach. This is because the role of soft factors in shaping flood risk perception is increasingly important. The importance of the context in the research on the perception of flood risk has slowly begun to be recognized also in the reviews. For example, Raška (2015) perceives the causes of differences in the perception of environmental hazards (e.g., flood risk) occurring between residents of Western Europe and Central and Eastern Europe in different political and cultural contexts (historically conditioned). The post-communist political system (once ensuring a strong position of central government bodies) of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe shape the current passive attitude of the communities of these countries toward floods. In societies of Central and Eastern Europe, decentralized and liberalized as a result of systemic transformation, prevailing materialistic orientation causes greater anxiety and awareness of environmental threats than for the citizens of Western European countries with a post-materialist orientation. Moreover, Boholm (1998) reviews the results of international research draws attention to their diversity, which may result from different geographical, national, and cultural contexts of the studied countries.

In their review, Kuhlicke et al. (2020) highlight the need to embed FRM and its practice within larger sociopolitical structures. In formulating future research directions, they note the need to answer the question "how the respective societal context produces specific patterns of vulnerability with respect to flood events?" (Kuhlicke et al. 2020, p. 13). They are of the opinion that researchers need to be sensitized to social processes and structures that can help explain specific patterns of vulnerability. According to them "there is (…) a need to develop a more nuanced understanding of which contextual factors shape households capacities. However, to allow for comparison of empirical insights generated by studies conducted in different contextual settings, we argue that a stronger theoretical underpinning of research in this intellectual catchment is needed to be able to produce empirical evidences that are comparable across different contexts" (Kuhlicke et al. 2020, p. 12). As they aptly note, Comparative research could contrast and confirm results for different adaptation measures or different contexts. Attems et al. (2020) noted that, in fact, the influence of factors on individual behavior toward risk is quite complex, as different sociocultural and individual circumstances influence the individual behavior of individuals. Furthermore, according to Andráško (2021), the interrelationship between flooding and social processes is receiving increasing attention in flood risk management research. The role of the social environment is so far an under-researched area of flood risk research. Many social or sociopsychological theories and approaches are still not used to study perceptions and behaviors related to flooding. Andráško (2021) sees a need for further research into the (nature of) the relationship of socio-demographic characteristics with other factors of flood risk behavior, and a research gap regarding the study of the role of emotional ties and local identities in shaping risk behavior. As he aptly postulates, flood risk research should aim not only to identify factors, but also to determine how they are interrelated.

However, complete disregard for the rationalist approach is not possible in studies of flood risk perception. It should not be replaced by research in the constructivist paradigm but only constantly supplemented. Notably, the constructivist and rationalist perspectives are insufficiently reliable and credible. As Renn (1989) aptly points out, they are unable to provide solid guidance on their own, and public values, rational decision-making, and scientific knowledge should be reconciled through a “well-managed discourse.”

In connection with the above, there is a need to revive the study of flood risk perception toward a more holistic view, namely the development of a constructivist approach to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting the perception of flood risk. The constructivist paradigm therefore recommends a more comprehensive analysis of how the sociocultural context shapes a broader understanding of risk. Research teams should include geographers and scientists representing other scientific disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, cultural studies, religious studies, ethnography, political science, history, social communication, and media.

Flood risk research has great potential to combine natural and social sciences. However, the fusion of theories derived from these two research areas is extremely difficult and caution must be exercised. The ontological, epistemological, axiological, and ethical foundations of these theories are often fundamentally different, with the result that the individual theories are not necessarily mutually compatible.

The postulated direction of flood risk research is part of the research concepts of vulnerability, capacity, and resilience. It closely refers to the innovative approach to developing a social resilience model, which would be based, among other things, on the perception of flood risk (Bradford et al. 2012). The concept of resilience assumes a positive adaptation of society to the existing developmental threats. A resilient society is one that adapts continuously and flexibly to changing circumstances. Community resilience has been highlighted as one of four priority mechanisms for disaster risk reduction worldwide (Schelfaut et al. 2011). The role of risk perception in improving the resilience of people and communities is widely recognized as an important part of the wider area of risk research (Burns and Slovic 2012). Risk perception is often viewed as a key element of vulnerability assessment.

In many studies, the perception of risk is considered a factor of vulnerability (e.g., Messner and Meyer 2006; Kuhlicke et al. 2011), but we can agree with Brikholz et al. (2014) that they rarely elaborate on the perception of flood risk in a substantive manner. Some resilience studies often consider the important role of risk perception as an argument for better risk communication in flood management strategies (e.g., Schelfaut et al. 2011). However, based on the literature on flood risk management, the perception of Kuhlicke and Steinführer (2013) is that the concept of resilience is largely in its infancy, and we agree. At present, relatively few empirical studies have examined the perception of flood risk in terms of resilience. The statement in Brikholtz et al. (2014, p. 15) that the concept of resilience "should, we argue, be used to greater effect in underpinning flood risk research" exactly corresponds to the recommendations made in this work regarding a renewed research agenda for flood risk perception.

References

Andráško I (2021) Why people (do not) adopt the private precautionary and mitigation measures: a review of the issue from the perspective of recent flood risk research. Water 13(140)

Armas I, Ionescu R, Posner CN (2015) Flood risk perception along the Lower Danube river, Romania. Nat Hazards 79:1913–1931

Attems M-S, Thaler T, Genovese E, Fuchs S (2020) Implementation of property-level flood risk adaptation (PLFRA) measures: choices and decisions. WIREs Water 7(e1404)

Baan PJA, Klijn F (2004) Flood risk perception and implications for flood risk management in the Netherlands. Int J River Basin Manag 2(2):1–10

Bamberg S, Masson T, Brewitt K, Nemetschek N (2017) Threat, coping and flood prevention—A meta-analysis. J Environ Psychol 54:116–126

Barnett J, Breakwell GM (2001) Risk perception and experience: hazard personality profiles and individual differences. Risk Anal 21(1):171–177

Becker G, Aerts JCJH, Huitema D (2013) Influence of flood risk perception and other factors on risk-reducing behaviour: a survey of municipalities along the Rhine. J Flood Risk Manag 7(1):16–30

Bera MK, Daněk P (2018) The perception of risk in the flood-prone area: a case study from the Czech municipality. Disast Prev Manag 27(1):2–14

Bichard E, Kazmierczak A (2012) Are homeowners willing to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change? Clim Chang 112:633–654

Biernacki W, Bokwa W, Działek J, Padło T (2009) Społeczności lokalne wobec zagrożeń przyrodniczych i klęsk żywiołowych. Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Kraków

Birkholz S, Muro M, Jeffrey P, Smith HM (2014) Rethinking the relationship between flood risk perception and flood management. Sci Total Environ 478:12–20

Boholm A (1998) Comparative studies of risk perception: a review of twenty years of research. J Risk Res 1(2):135–163

Botzen WJW, van den Bergh JCJM (2012) Monetary valuation of insurance against flood risk under climate change. Int Econ Rev 53(3):1005–1026

Botzen WJW, Aerts JCJH, van den Bergh JCJM (2009a) Willingness of homeowners to mitigate climate risk through insurance. Ecol Econ 68:2265–2277

Botzen WJW, Aerts JCJH, van den Bergh JCJM (2009b) Dependence of flood risk perceptions on socioeconomic and objective risk factors. Water Resour Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009WR007743

Bourdieu P (2010) Distinction.Bradford R A, O’Sullivan J J, van der Craats I M, Krywkow J, Rotko P, Aaltonen J, Bonaiuto M, De Dominici S, Waylen K, Schelfaut K (2012) Risk perception – issues for flood management in Europe. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 12:2299–2309

Bradford RA, O’Sullivan JJ, van der Craats M, Krywkow J, Rotko P, Aaltonen J, Bonaiuto M, De Dominici S, Waylen K, Schelfaut K (2012) Risk perception – issues for flood management in Europe. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 12:2299–2309

Bubeck P, Botzen WJW, Aerts JCJH (2012) A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior. Risk Anal 32(9):1481–1495

Burningham K, Fielding J, Thrush D (2008) “It’ll never happen to me”: understanding public awareness of local flood risk. Disasters 32(2):216–238

Burns WJ, Slovic P (2012) Risk perception and behaviors: anticipating and responding to crises. Risk Anal 32:579–582

Burton C, Cutter S (2008) Levee failures and social vulnerability in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Area, California. Nat Hazards Rev 9 (Special issue: Flooding in the Central Valley) 136–149

Burton I, Kates R, Mather JR, Snead RE (1965) The shores of megalopolis: coastal occupance and human adjustment to flood hazard. Publications in climatology 18 (3)

Bustillos Ardaya A, Evers M, Ribbe L (2017) What influences disaster risk perception? Intervention measures, flood and landslide risk perception of the population living in flood risk areas in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 25:227–237

Colten CE, Sumpter AR (2009) Social memory and resilience in New Orleans. Nat Hazards 48(3):355–364

Cutter SL, Boruff BJ, Shirley WL (2003) Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc Sci Q 84:242–261

Dake K (1991) Orientating dispositions in the perceptions of risk: an analysis of contemporary worldviews and cultural biases. J of Cross-Cult Psychol 22:61–82

Douglas M, Wildavsky AB (1982) Risk and culture: an essay on the selection of technical and environmental dangers. Berkeley University of California Press, California

Douglas M (1978) Cultural bias. occasional paper no. 35. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, London

Douglas M. (1992) Risk and Blame. Routledge London

Drake K (1992) Myths of nature: culture and the social construction of risk. J Soc Issues 48(4):21–37

Duží B, Vikhrov D, Kelman I, Stojanov R, Juřička D (2015) Household measures for river flood risk reduction in the Czech Republic. J Flood Risk Manag. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12132

Działek J, Biernacki W, Bokwa A (2013) Challenges to social capacity building in flood-affected areas of southern Poland. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 13:2555–2566

Działek J, Biernacki W, Bokwa A (2014) Impact of Social capital on local communities’ response to floods in Southern Poland In: Neef A, Shaw R (ed.) Risks and conflicts: local responses to natural disasters (Community, Environment and Disaster Risk Management, Volume 14) Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp.185 - 205

Englander T, Farago K, Slovic PA (1986) Comparative analysis of risk perception in Hungary and the United states. Soc Behav 1:55–66

Finucane ML, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson SM (2000) The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J Behav Decis Mak 13:1–17

Fischhoff B, Slovic P, Lichtenstein S, Read S, Combs B (1978) How safe is safe enough - psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sci 9(2):127–152

Fitton SL, Moncaster A, Guthrie P (2015) Investigating the social value of the Ripon rivers flood alleviation scheme. J Flood Risk Manag. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12176

Flynn J, Slovic P, Mertz CK (1994) Gender, race and environmental health risks. Risk Anal 14:1101–1108

Fox-Rogers L, Devitt C, O’Neill E, Brereton F, Clinch JP (2016) Is there really “nothing you can do”? Pathways to enhanced flood-risk preparedness. J Hydrol 543(Part B):330–343

Fritsche I, Barth M, Jugert P, Masson T, Reese G (2018) A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol Rev 125:245–269

Giddens A (1979) Central problems in social theory: Action, structure and cntradiction in social analysis

Goszczyńska M, Tyszka T, Slovic P (1991) Risk perception in Poland: a comparison with three other countries. J Beha Deci Mak 4:179–193

Grothmann T, Reusswig F (2006) People at risk of flooding: why some residents take precautionary action while others do not. Nat Hazards 38(1–2):101–120

Gustafson PE (1998) Gender differences in risk perception: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Anal 18(6):805–811

Harries T, Penning-Rowsell E (2011) Victim pressure, institutional inertia and climate change adaptation: the case of flood risk. Glob Environ Change 21:188–197

Heitz C, Spaeter S, Auzet AV, Glatron S (2009) Local stakeholders’ perception of muddy flood risk and implications for management approaches: a case study in Alsace (France). Land Use Policy 26:443–451

Ho C, Shaw D, Lin S, Chiu YC (2008) How do disaster characteristics influence risk perception? Risk Anal 28(3):635–643

Hung HC (2009) The attitude towards flood insurance purchase when respondents’ preferences are uncertain: a fuzzy approach. J Risk Res 12(2):239–258

Johnson EJ, Tversky A (1983) Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. J Pers Soc Psychol 45:20–31

Johnson JG, Wilke A, Weber EU (2004) Beyond a trait view of risk-taking: a domain- specific scale measuring risk perceptions, expected benefits, and perceived-risk attitude in German-speaking populations. Polish Psychol Bull 35:153–172

Karpowicz-Lazreg C, Mullet E (1993) Societal risk as seen by the French public. Risk Anal 13:253–258

Kates RW (1963) Perceptual regions and regional perception in floodplain management. Pap Proc Reg Sci as 11:217–227

Kellens W, Zaalberg R, Neutens T, Vanneuville W, De Maeyer P (2011) An Analysis of the public perception of flood risk on the Belgian Coast. Risk Anal 3(7):1055–1068

Kellens W, Terpstra T, Schelfaut K, De Maeyer P (2013) Perception and communication of flood risks: a literature review. Risk Anal 33(1):24–49