Abstract

Delivery of neuropsychological interventions addressing the cognitive, psychological, and behavioural consequences of brain conditions is increasingly recognised as an important, if not essential, skill set for clinical neuropsychologists. It has the potential to add substantial value and impact to our role across clinical settings. However, there are numerous approaches to neuropsychological intervention, requiring different sets of skills, and with varying levels of supporting evidence across different diagnostic groups. This clinical guidance paper provides an overview of considerations and recommendations to help guide selection, delivery, and implementation of neuropsychological interventions for adults and older adults. We aimed to provide a useful source of information and guidance for clinicians, health service managers, policy-makers, educators, and researchers regarding the value and impact of such interventions. Considerations and recommendations were developed by an expert working group of neuropsychologists in Australia, based on relevant evidence and consensus opinion in consultation with members of a national clinical neuropsychology body. While the considerations and recommendations sit within the Australian context, many have international relevance. We include (i) principles important for neuropsychological intervention delivery (e.g. being based on biopsychosocial case formulation and person-centred goals); (ii) a description of clinical competencies important for effective intervention delivery; (iii) a summary of relevant evidence in three key cohorts: acquired brain injury, psychiatric disorders, and older adults, focusing on interventions with sound evidence for improving activity and participation outcomes; (iv) an overview of considerations for sustainable implementation of neuropsychological interventions as ‘core business’; and finally, (v) a call to action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

In Australia, and many other countries around the world, the role of the clinical neuropsychologist in diagnostic assessment has long been emphasised, recognising the specialised skills neuropsychologists bring to identifying the presence, extent, and impact of cognitive and psychosocial sequelae associated with brain conditions across the lifespan. However, given its fundamental origins in human psychology and behaviour, its biopsychosocial approach to understanding individuals with brain conditions, and its emphasis on evidence-based practice, clinical neuropsychology also provides an invaluable framework for developing, providing, and evaluating interventions that target cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and psychosocial difficulties to improve overall functioning. New technologies that assist with diagnosis of brain conditions have led to a changing role of clinical neuropsychologists, with an increasing focus on the delivery of effective interventions.

Despite a long history of research and practice in neuropsychological interventions (Brouwer, 2002; Ponsford et al., 1995; Zangwill, 1947) and a quickly growing evidence base (Wilson, 2017), this aspect of clinical neuropsychological practice remains under-recognised among medical specialists, allied health practitioners, health policy-makers, and the lay public in many Australian settings (exemplified by the Stroke Foundation’s, 2020 Rehabilitation Services audit: https://informme.org.au/stroke-data/Rehabilitation-audits). This limits our ability to optimally contribute to patient care and management. Many neuropsychologists in Australia lack confidence in delivering neuropsychological interventions, at least partly due to limited opportunities for supervised practice during postgraduate training (Wong et al., 2014). These factors have led to gaps in the understanding and delivery of neuropsychological interventions in Australian clinical settings, which limits access to evidence-based care for individuals with brain conditions (e.g. Andrew et al., 2014; Naismith et al., 2022). We hope that this clinical guidance paper will represent one step towards addressing this lack of access. In response to changes to the opportunities available for funding neuropsychological interventions in Australia (e.g. the National Disability Insurance Scheme) and in order to open up further funding avenues (e.g. Medicare), it is imperative that we have high quality evidence for these interventions, and that our training programs are equipping clinical neuropsychologists with the competencies necessary to deliver evidence-based interventions effectively.

Aims

This clinical guidance paper aims to provide an overview of key considerations in the effective delivery of neuropsychological interventions; clinical competencies important for intervention delivery; and clinical implementation of evidence-based interventions, alongside a summary of available evidence for their efficacy in the following populations:

-

Acquired brain injury/illness (including stroke, traumatic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis);

-

Psychiatric conditions (including early psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and eating disorders);

-

Older adults (ranging from healthy ageing through mild cognitive impairment to dementia).

We acknowledge that this is not an exhaustive list of the potential groups with which neuropsychological interventions can be conducted; however, both research and practice are the most prominent in these cohorts. The evidence-based practice principles outlined both generally and for these specific groups are likely to apply to interventions delivered with people with other primary diagnoses (e.g. adult ADHD), although clinicians are encouraged to explore the evidence base for these specific cohorts to determine which approaches or techniques may be most appropriate and effective. Pragmatically, and in recognition of the unique clinical, psychosocial, and environmental parameters of relevance to interventions in children and adolescents, only neuropsychological interventions conducted with adult and older adult populations will be included in this clinical guidance paper.

We do not aim to provide a systematic or meta-analytical review of the evidence, as in many cases, this has been done previously. Where available, we will draw on and cite such existing reviews (see ‘Resources’ section for a list of key systematic reviews). We have also not performed a systematic appraisal of the quality of evidence for each intervention type, as would be expected for formal clinical guidelines (which is one of the reasons we have termed this a ‘clinical guidance paper’). This is because there is a large number of cognitive, psychological and behavioural interventions reviewed for each cohort, and to provide a systematic appraisal of evidence quality would be a very substantial undertaking that was beyond the scope of this paper. Rather, we have provided a synthesis of existing findings, particularly regarding the nature of available evidence for interventions with meaningful impacts on everyday life, as well as guidance and recommendations for a ‘best practice’ approach to incorporating these interventions clinically.

In doing so, we also aim to:

-

(i)

Outline the role of clinical neuropsychologists in delivering neuropsychological interventions in Australia, while acknowledging interstate variability in training and roles within the public and private healthcare systems;

-

(ii)

Highlight issues to consider in the planning and implementation of neuropsychological interventions for various patient groups;

-

(iii)

Address key issues impacting the effectiveness of neuropsychological interventions, relating to the (a) client, (b) clinician, and (c) intervention technique;

-

(iv)

Recognise the role and value of neuropsychological interventions in collaboration with other allied health and medical disciplines (e.g. occupational therapy, speech pathology).

We anticipate this paper may provide a starting point for future development of formal clinical guidelines regarding the use of neuropsychological interventions. At a broader level, we hope this paper may also provide an impetus for further collaborative and multidisciplinary research into developing, evaluating, and implementing neuropsychological interventions in Australia and internationally.

Intended Audience

This clinical guidance paper is aimed primarily at clinical neuropsychologists with involvement, or intended involvement, in delivering neuropsychological interventions across a range of populations. It may also be useful for clinicians and researchers in other disciplines working within a multidisciplinary setting, where neuropsychological interventions may represent a component of a team-based therapeutic approach. In this case, the evidence and issues discussed herein may provide some context and parameters around the utility or expected outcomes from the neuropsychological intervention and how it may best be integrated alongside other medical or allied health interventions. Communication to our multidisciplinary colleagues about the potential benefits that neuropsychologists can offer was a critical need identified by Kubu et al. (2016); indeed, access to guidance papers detailing the value of neuropsychology was one of their specific recommendations.

We acknowledge that this paper has been written in the Australian context and that some issues (particularly relating to training, work roles, or funding) may differ in other countries. We have acknowledged these differences wherever relevant throughout the paper. We welcome commentary and perspectives from international colleagues about how the contents of this paper may apply in other countries.

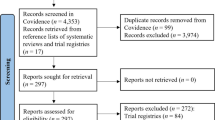

Development and Methodology

The concept for this paper was initially raised by Professor Sharon Naismith, following a symposium she led on this topic at the annual conference of the Australian Psychological Society’s College of Clinical Neuropsychologists (CCN), held in Melbourne, Victoria, September 2016.

The proposal was supported and a working party convened, comprising a network of clinical neuropsychologists actively working or researching the development, evaluation, or implementation of neuropsychological interventions. With support from Professor Naismith, A/Prof Dana Wong and Dr Loren Mowszowski were voluntarily appointed as co-chairs. Potential working party members were identified through professional networks and invited to participate on a voluntary basis. An effort was made to engage members throughout Australia, while limiting the number of members to a maximum of 15, to maintain project feasibility.

Once convened, the working party communicated via emails and teleconferences to develop a proposed outline regarding the aims of the paper, the populations to include, and key additional issues to include in the discussion (see the ‘Aims’ section, above). Subsections were allocated on a voluntary basis and according to areas of specialised skill or expertise.

The proposed paper outline was presented at an Open Forum event to delegates of the CCN’s annual conference in Perth, Western Australia (November 2017). Approximately 40 people attended the Open Forum, mostly neuropsychologists. During the forum, the working party requested feedback, comments, and suggestions from attendees regarding the proposed aims and outline of the clinical guidance paper. This feedback was documented, subsequently relayed to working party members not in attendance, and the aims and outline were amended accordingly. We note that few amendments were requested.

Thereafter, the working party proceeded to draft the paper according to their allocated subsections. All working party members reviewed each subsection and the entire paper to ensure consensus, consistency, and completeness. In April 2018, a paper draft was forwarded to the CCN Executive Committee, who provided feedback in September 2018. The working party subsequently amended the paper taking into consideration these comments and any updates in the field. Following this iterative process, a second draft was distributed to the CCN Executive Committee and overseeing expert Professor Sharon Naismith in 2020–2021. A presentation was also made to over 100 people outlining the contents of the paper as part of a CCN webinar (though non-CCN members also attended) in 2021, and attendees were invited to provide feedback, which was constructive and positive. Further revisions were made by the working party in 2021, with the revised version distributed to the CCN membership (966 members, including student members) for feedback towards the end of 2021. Respondents to this consultation supported the accuracy, clarity, and organisation of the contents, issues covered, evidence base, and usefulness of the paper. Feedback from respondents was considered when preparing the final version. Although CCN members were consulted, the expert working group are responsible for the contents of the paper.

Section 1: Characterising Neuropsychological Interventions

Defining Neuropsychological Interventions

There are multiple ways in which ‘neuropsychological interventions’ could be defined. For this clinical guidance paper, we define a neuropsychological intervention as an intervention that targets the cognitive, emotional, psychosocial, and/or behavioural consequences of conditions affecting the brain.

There are several points we wish to note about this definition. Firstly, we have chosen not to define ‘neuropsychological interventions’ according to the type or content of the intervention, as these are numerous. However, for the purpose of this paper, we will classify neuropsychological intervention types into the following main categories:

-

(i)

Psychoeducation (including feedback after neuropsychological assessment)

-

(ii)

Cognitive remediation/rehabilitation (encompassing restorative and compensatory approaches)

-

(iii)

Psychological therapies (e.g. cognitive behaviour therapy)

-

(iv)

Behaviour management (e.g. positive behaviour support plans)

-

(v)

Environmental modifications and supports

These categories are very similar to those used by Wong et al. (2014) in their survey about the experiences of Australian neuropsychology graduates in delivering neuropsychological interventions. However, we acknowledge there are many variations in the labelling of these intervention types. This is particularly true for cognitive remediation/rehabilitation, which can encompass cognitive training, stimulation, and management using compensatory strategies, among other things. Throughout this paper, where evidence is specific to a particular intervention type, descriptive details will be included for clarity. It is also worth noting that categorising interventions by type or technique may falsely imply that these intervention types are standalone or separate; however, many neuropsychological interventions incorporate content from several of these categories and may be delivered in conjunction with other interventions (e.g. speech pathology, occupational therapy, medical or lifestyle interventions).

We also acknowledge there are other types of interventions that may be used to improve cognition or brain function, including pharmacological interventions and brain stimulation approaches (e.g. transcranial magnetic stimulation). We consider these types of interventions to be outside the scope of this clinical guidance paper, given (i) these interventions are not usually delivered by or accessible to clinical neuropsychologists, and (ii) most of these interventions have little evidence supporting their impact beyond the impairment level — i.e. at the level of activity and/or participation (see the next point). If either the accessibility or evidence for these other types of interventions changes, they could be included in updates to this clinical guidance paper.

Throughout the paper, we will use the International Classification of Function (ICF; World Health Organization, 2013) as a framework within which neuropsychological interventions can be understood and evaluated. In describing disability, this model distinguishes between ‘body functions and structure’ (e.g. impairment on memory tests), ‘activity limitation’ (e.g. forgetting appointments), and ‘participation’ (e.g. not being able to work due to memory difficulties), as shown in Fig. 1. Outcome evaluation often targets the impairment level, by measuring the impact of the intervention on test performance. However, we contend that the outcomes of neuropsychological interventions should also be evaluated in broader terms, that is, regarding their impact at the levels of activity limitation and participation restrictions and overall quality of life. Fundamentally, the aim of neuropsychological interventions is to improve everyday functioning to make a meaningful difference to the life of the person with the brain condition. The level of the ICF model at which outcomes have been evaluated will therefore be noted throughout.

ICF model as applied to conditions affecting the brain, adapted from World Health Organization (2013)

Delivering Effective Neuropsychological Interventions: Key Principles

While the evidence base for neuropsychological interventions has developed largely separately in different clinical populations, there are several key principles or considerations for the effective delivery of interventions that apply broadly. In this section, we introduce these general principles, which relate to the (a) client, (b) clinician, and (c) intervention.

Client-Related Factors

Using a Biopsychosocial Case Formulation Framework

Neuropsychological interventions should be founded on a comprehensive biopsychosocial case formulation considering biological, psychological, and social factors (Wilson, 2002) as depicted in Fig. 2.

A comprehensive assessment of all these factors is therefore strongly recommended when planning a neuropsychological intervention, so the intervention can be tailored accordingly. For example, consider the following individuals, referred for intervention targeting their everyday memory difficulties:

-

John, a 39-year-old roof tiler, who had a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) 6 months ago after falling from a ladder at work; has pre-existing sleep apnoea; lacks insight into his memory impairment; is apathetic with low levels of daily physical and mental activity; has low motivation to change; takes benzodiazepines more often than recommended; and whose wife works full-time while supporting their three young children and is very distressed;

-

Sarah, a 23-year-old medical student, recently diagnosed with multiple sclerosis; has everyday memory difficulties that appear to be closely related to her attentional abilities and fatigue; has a history of anxiety and perfectionism; is highly motivated to finish her medical degree; and lives at home with her parents who are of Indian background and are resistant to the idea of Sarah seeing a psychologist;

-

Brian, a 72-year-old farmer in a remote area, with possible early Alzheimer’s dementia; history of diabetes (with inconsistent medication adherence), cardiovascular disease, and depression; is the sole carer for his wife who has late-stage cancer; has been forgetting to feed the farm animals; is currently drinking at least four beers every night; distrusts doctors; has been told he should have a driving assessment and may lose his licence.

For each of these people, the content, timing, location, mode of delivery, sequence of intervention elements, and involvement of family in the memory intervention need tailoring according to their individual biopsychosocial formulation; as a one-size-fits-all approach is highly unlikely to be effective. For example, for John, behavioural and psychological interventions to address his apathy and motivational issues may need to be addressed prior to engaging him in memory rehabilitation strategies, while prioritising concurrent support for his wife (e.g. with a social worker). For Sarah, a focus on her study skills may enable engagement with a psychologist in the context of her family’s beliefs, and integrating fatigue and anxiety management strategies with memory interventions would be important. For Brian, establishing practical supports (e.g. through aged care services) to ensure the safety of his wife, farm animals, and other drivers would be of primary importance, along with memory and organisational strategies to ensure medication adherence.

Considering the Impact of Time Post-onset and Trajectory of Change

The nature of the neuropsychological intervention should also be tailored according to time since onset of the brain condition, and likely trajectory of the illness or injury. In the case of acquired brain injury (ABI), interventions in the first 6–12 months might focus on enhancing recovery and providing psychoeducation, with a later focus on managing and compensating for the residual effects of the ABI. In contrast, for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, in the early stages, interventions may focus on strategies used by the client themselves, whereas in later stages the interventions are likely to focus on family and environmental supports. For psychiatric disorders, interventions need to account for whether the mental illness is in an acute phase or remission and may also need to target issues such as risk of recurrence alongside improvement.

Clinician-Related Factors

Ensuring Clinicians Have the Appropriate Competencies

The clinician delivering the neuropsychological intervention should ensure they have the necessary competencies and resources to deliver the intervention effectively. This often involves additional training and/or supervised practice beyond that received in the context of university training programs. This topic is reviewed more comprehensively in ‘Section 2: Acquiring Competencies in Neuropsychological Interventions’.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Where possible, interdisciplinary approaches to management of individuals and families with brain conditions are recommended, throughout the continuum of care in hospital and community settings. This allows discipline-specific expertise to be integrated to work towards the client’s goals. Neuropsychological interventions are therefore often ideally delivered in an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary context, together with other medical and allied health interventions and with the input of team members from other disciplines (Pagan et al., 2015) to determine priorities for targeted and timely intervention. For neuropsychologists working in private practice, there may be fewer opportunities to work within a multidisciplinary team. However, regular consultation and communication of treatment targets, plans, and progress to other health professionals involved in the person’s care (including the general practitioner or primary care physician) can be helpful in ensuring collaborative work towards common goals. Training that includes a multidisciplinary focus will provide team members with a necessary understanding of shared or complementary areas of practice in addition to more discipline-related expertise, assuring effective teamwork (Pagan et al., 2015).

Intervention-Related Factors

Intervention Targets Should Be Person-Centred and Goal-Directed

Neuropsychological interventions should adopt a collaborative goal-setting approach, where person-centred goal(s) are set and refined as a key part of the intervention and progress towards the goal(s) is actively monitored. Goals should be set by the client; however, clinicians often need to assist clients in ‘unpacking’ their goals to ensure that the goals are SMART (outlined in Fig. 3).

Inevitably, family members, caregivers, and other stakeholders (e.g. employers) may also wish to contribute to goal development. While it can be difficult to navigate these potentially differing perspectives, the clinician’s role is to prioritise person-centred care. This includes balancing the needs of the client and ensuring they have adequate opportunity and means to communicate their wishes and opinions, while respectfully and constructively considering input from relevant others (in accordance with the biopsychosocial framework, as above). It can be helpful to define the roles of the treatment team and explain the person-centred approach to all involved parties at the outset of the intervention.

Interventions Should Be Evidence-Based

Techniques and approaches with the strongest level of available evidence should be selected. Figure 4 shows the hierarchy of evidence that should be used to guide the choice of neuropsychological intervention.

In evaluating the evidence, clinicians should consider not just the strength and quality of the evidence for the overall efficacy of a particular intervention, but also:

-

Known predictors or moderators of intervention outcome, and how these apply to the client in question;

-

Whether or not the intervention outcome was clinically significant or meaningful, not just statistically significant; and

-

Whether the outcomes were measured at the levels of activity and participation as well as impairment, given the overall aim of optimising quality of life.

Tools such as NeuroBITE (https://neurorehab-evidence.com/web/cms/content/home) and CogTale (https://cogtale.org/) can be useful resources to help clinicians evaluate the available evidence for particular interventions. It is important that clinicians can justify their choice of neuropsychological intervention based on the available evidence, the patient’s goals and preferences, their biopsychosocial context, and the clinical setting. As stated by van Heugten (2017, p. 22), ‘planning treatment explicitly and evaluating the outcome should therefore be a self-evident process, either by monitoring the individual patient or applying the best available evidence in a careful and judicious manner’.

Optimising Frequency/Duration/Intensity

In planning the neuropsychological intervention, consideration should be given to the frequency and duration of intervention sessions, and the total duration of the intervention period. Decisions about these factors should be based on available evidence for the efficacy of the intervention techniques under consideration, as well as in relation to the client’s circumstances, client goals, and feasibility (e.g. availability of clinicians, funding, geographical location of client, resources required to implement the intervention).

Choosing the Appropriate Context/Location and Mode of Delivery

Neuropsychological interventions targeting a particular presenting problem (e.g. attentional difficulties, social anxiety) can be delivered in a range of contexts and modalities. These include home-based or centre-based locations, individual or group formats, computerised or clinician-facilitated programs, and telehealth or face-to-face delivery. Again, decisions about the context and mode of delivery of a neuropsychological intervention should be based on the available evidence for that intervention type, as well as the client’s circumstances, goals, and feasibility (e.g. availability of services, technological proficiency of client, geographical location of client).

Enhancing Generalisability and Maintenance

Key elements of the effectiveness of a neuropsychological intervention include its ability to generalise to daily life roles and activities that have not been directly targeted in the intervention; and for its effects to be sustained beyond the period of intervention. Ideally, neuropsychological interventions that have demonstrated evidence of both generalisability and maintenance should be selected, and in delivering the intervention, clinicians should also actively discuss with clients how best to apply or incorporate the intervention techniques into their daily lives, both during and beyond the intervention period. Clinicians and researchers should also include some evaluation of generalisability and maintenance as part of their outcome measurement.

Using Meaningful Outcome Measures

Both clinicians and researchers should select appropriate measures to evaluate the outcomes of neuropsychological interventions, which are meaningful and relevant to client goals, as well as reliable and valid. Even if the intervention targets an impairment (i.e. at the bodily functions and structures level of the WHO ICF framework), the outcomes of the intervention should also be measured at the levels of activity and participation. This means including measures that capture everyday activities and participation in life roles such as work and leisure. Measuring goal attainment, for example using Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), is a clinically useful way to capture progress on personally meaningful outcomes. Using GAS in addition to validated questionnaires measuring relevant activity and participation outcomes can together capture the outomes that are most important to the person. Furthermore, measures of health-related quality of life and wellbeing (which are not incorporated particularly well within the ICF framework) are also important and capture unique and important outcomes that can influence policy-makers deciding where to allocate resources. For measuring health-related quality of life, clinicians and researchers should be clear in selecting and reporting the perspective(s) used – i.e. self or carer. These are complementary perspectives and provide valuable information when used concurrently (Bosboom et al., 2012; Burks et al., 2021). Efforts should also be made by researchers to use consistent outcome measures when evaluating neuropsychological interventions, particularly those that target the same presenting issue or clinical population. Lists of recommended outcome measures have been compiled for adult TBI (Honan et al., 2017), brain impairment generally (Tate, 2010), and in the older adult field (Simon et al., 2020).

Consideration of Costs and Benefits

Clinicians and researchers should also consider the cost-effectiveness of neuropsychological interventions. These interventions are generally delivered in resource-constrained settings, whether funded through the government (e.g. primary health networks), insurance agencies, or the client. Therefore, the best interventions are not always those that have the best efficacy, if the margin of improved efficacy is slim but the cost increase is large compared with the next most effective intervention. In other words, a good neuropsychological intervention should deliver ‘bang for your buck’. Appraisal of costs and benefits can be particularly challenging where there may be several ways to deliver an intervention (e.g. group vs individual; face-to-face vs. telehealth), or where decisions must be made to use resources to deliver fewer interventions to more clients or more interventions to fewer clients. Cost-effectiveness is re-visited in ‘Section 4: Implementation of Neuropsychological Interventions into Health Services’.

Section 2: Acquiring Competencies in Neuropsychological Interventions

Which Competencies Are Required for Effective Delivery of Neuropsychological Interventions and How Should Clinical Neuropsychologists Be Trained?

A key challenge for the clinical practice of evidence-based neuropsychological interventions is training clinicians to be competent to deliver them effectively. This is one of the primary barriers to more widespread clinical implementation of interventions, with many neuropsychologists not feeling confident or competent enough to incorporate neuropsychological interventions into their clinical roles, at least in Australia (Wong et al., 2014). In their review of the implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments, McHugh and Barlow (2010) argue that the greatest challenge to dissemination is training clinicians who can competently administer these therapies. As they highlight, successful training of clinicians in evidence-based psychological therapies requires a balance of both didactic training (i.e. knowledge transfer through written materials and workshops) and competence training (i.e. acquiring the skills needed for delivering the treatment effectively, usually through supervised practice). The importance of training competent clinicians was also highlighted by Powell et al. (2012), in their review of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in mental health.

There have been several attempts to develop lists of foundational knowledge- and skill-based competencies for neuropsychological interventions (Rey-Casserly et al., 2012; Smith & CNS, 2018), and very recently, training pathways and competencies for ‘neurorehabilitation psychology’ (Stucky et al., 2023). In one of the most recent and comprehensive of these efforts, a group of American organisations calling themselves the Clinical Neuropsychology Synarchy (Smith & CNS, 2018) outlined five knowledge-based and seven applied intervention competencies. These CNS intervention competencies were recently further expanded by the Australian Neuropsychology Alliance of Training and Practice Leaders (ANATPL; Wong et al., 2023a). They indicated that clinical neuropsychologists should have knowledge of:

-

Evidence-based intervention techniques and practices to address cognitive, emotional, and behavioural consequences of conditions affecting the brain, with consideration of both the quality of the evidence and whether there is evidence for meaningful impact on everyday activities, participation in life roles, and quality of life in the relevant clinical population.

-

Theoretical and procedural bases of intervention methods appropriate to address disorders of attention, processing speed, learning and memory, executive skills, problem solving, language, perceptual and visuospatial skills, social cognition, psychological/emotional adjustment, and behaviours of concern.

-

How complex neurobehavioural disorders (e.g. anosognosia, neuropsychiatric conditions) factors can affect the applicability of interventions.

-

Sociocultural considerations when planning and using interventions, referring on to other providers with specialised competence if appropriate, and/or seeking cultural consultation as required.

-

How to promote cognitive health with patients through activities such as physical exercise, cognitive stimulation, stress management, and healthy lifestyle (e.g. sleep, nutrition) practices.

-

Empirically supported interventions provided by other psychologists and other mental and behavioural health professionals.

In terms of applied competencies, they indicated that clinical neuropsychologists should be able to:

-

Identify targets of interventions and client goals and preferences.

-

Employ neuropsychological assessment and provision of feedback for therapeutic benefit.

-

Provide psychoeducation and information about neuropsychological disorders to aid the patient and family’s understanding of their presenting concerns and how to manage them.

-

Identify potential barriers to intervention and adapt interventions to minimise such barriers.

-

Develop a comprehensive biopsychosocial case formulation, including the cultural context, which usefully guides the intervention.

-

Develop and implement treatment plans for neuropsychological problems based on the case formulation and client goals.

-

Implement evidence-based cognitive interventions for neuropsychological disorders across the lifespan.

-

Deliver evidence-based psychological therapies (e.g. for depression, anxiety) appropriately adapted for people with neuropsychological impairment.

-

Provide behavioural interventions (e.g. positive behaviour support) for behaviours of concern in people with neuropsychological disorders.

-

Consider suitability and provide adequate training and support for use of technologies within neuropsychological interventions (e.g. assistive technologies, telehealth).

-

Independently evaluate the effectiveness of interventions employing appropriate outcome measures that are meaningful in everyday life, relevant to the patient’s goals, reliable and valid.

-

Demonstrate an awareness of ethical and legal ramifications of neuropsychological intervention strategies.

While these foundational competencies apply generally to neuropsychological interventions, they do not describe how these competencies should be measured or benchmarked for specific intervention types. Many neuropsychological interventions require a unique and specialised set of skills that require specific training. It is therefore crucial to identify (1) which key competencies are required for effective delivery of each intervention, and (2) which methods for training clinicians are effective in enabling them to acquire those competencies. However, at present there is a paucity of evidence available to answer these questions. While there is a growing body of research on competencies and training in psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing (MI), this work cannot necessarily translate to psychological therapies that have been adapted for individuals with neuropsychological impairments, given the additional skills required for those adaptations to be successful. For example, Roth and Pilling (2007) published a useful framework describing the competencies required for effective CBT for depression and anxiety; however, it does not contain any competencies for adapting CBT techniques for people with impairments in domains of cognition that are important for deriving benefit from CBT, such as memory, cognitive flexibility, self-monitoring, and planning.

In terms of training, combined workshop training and ongoing supervision improved both community therapists’ skills and client outcomes in CBT for depression (Simons et al., 2010), and a similar combination of training methods resulted in the greatest gains in proficiency in clinicians learning MI (Miller et al., 2004). Again, however, treatment recipients in both studies did not have cognitive impairments associated with brain injury or illness. When modified for people with ABI, CBT, when delivered with booster sessions, has been found to be effective in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms over a six-month period (Ponsford et al., 2016). This manualised intervention has been published by ASSBI resources (Wong et al., 2019b). Recently, Wong et al. (2020) evaluated the impact of workshop training and three sessions of clinical supervision of delivery of this intervention on the competencies of a sample of primarily neuropsychologists. They found that a mix of didactic and competence training resulted in self-rated improvements in adapted CBT competencies, which were maintained over a 16-month period. This type of work has potential to reduce barriers to workplace practice of adapted CBT relating to clinician competence.

Further research has been conducted to identify competencies and training methods for other neuropsychological interventions, including development of a checklist of competencies required for group-based rehabilitation interventions (Wong et al., 2019a) and neuropsychological assessment feedback (Wong et al., 2023b). However, this body of research is at its early stages and much more work is needed to establish the evidence to guide the training of clinicians who are competent to deliver neuropsychological interventions. Nevertheless, the evidence so far consistently indicates that training in neuropsychological intervention skills should actively incorporate both didactic training (focused on knowledge acquisition) and competence training (focused on skill development); and that the competencies required sit at the crossroads of clinical neuropsychology and rehabilitation/intervention delivery (Stucky et al., 2023).

Current Training in Neuropsychological Interventions via Australian Clinical Neuropsychology Programs

At the time of writing and according to the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC) (www.psychologycouncil.org.au), training in clinical neuropsychology is offered by five accredited tertiary education providers across four states (New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, and Western Australia). APAC provides accreditation standards for psychology programs (including Masters, PhD, Doctor of Psychology), which are approved by the Psychology Board of Australia (PsyBA), our national psychologist registration body. In the most recent iteration of the APAC guidelines (Australian Psychology Accreditation Council, 2019), which came into effect in January 2019, APAC is responsible for determining the accreditation of clinical neuropsychology training programs and have specified minimal content requirements for these programs. Intervention competencies for clinical neuropsychology programs (Section 4.1.3 of the APAC guidelines) comprise only:

-

Selection, tailoring, and implementation of psychological interventions appropriate for clients and their needs, including rehabilitation, behaviour management, monitoring, and remediation;

-

Consultation with and referral to other professionals regarding the neuropsychological implications of neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms and disorders in a wider treatment context; and

-

Psychological interventions appropriate to the behavioural and cognitive dysfunctions associated with neuropathology.

Previously, clinical neuropsychology competencies and accreditation were determined and overseen by the Australian Psychological Society’s (APS) College Course Approval Guidelines for Postgraduate Specialist Courses drafted in late 2010 and published on the Psychology Board of Australia website in January 2011 (Australian Psychological Society, College of Clinical Neuropsychologists, 2011). These guidelines offer more detailed guidance regarding proficiency in neuropsychological interventions, specifying formal knowledge in theories of recovery (e.g. neural recovery and reorganisation; functional adaptation) as well as evidence-based models and techniques of neuropsychological intervention for neuropsychological disability. Section 4.2.d of the 2010 College Course Approval Guidelines includes::

-

Cognitive interventions for discrete cognitive impairments, such as visual neglect or memory disorder;

-

Cognitive behavioural approaches (e.g. anger management);

-

Psychotherapeutic approaches such as counselling;

-

A ‘lifespan perspective’ allowing for moderation of principles and techniques across stages of life;

-

Interdisciplinary teamwork and consultation; and

-

Evaluation of the implementation and outcomes of any intervention in order to determine its efficacy.

This is nevertheless a clearly shorter list than the more detailed competencies for neuropsychological interventions recommended by ANATPL (Wong et al., 2023a). These accreditation guidelines should therefore be considered a minimum baseline for intervention competencies for graduates. In addition, while the content and format of accredited clinical neuropsychology training programs must comply with accreditation guidelines, there is currently considerable variability between states and education providers in terms of their methods for supporting neuropsychological trainees in developing the practical skills to plan, deliver, and evaluate neuropsychological interventions in clinical and/or research practice. Thus, currently, a postgraduate qualification in clinical neuropsychology does not necessarily signify an equivalent level of competency in neuropsychological interventions across graduates. Clinicians must always be aware of their own boundaries in competent practice (as clearly stated in our standards of ethical professional conduct) and seek additional training and supervision in areas of practice in which they have not had the opportunity to acquire the relevant skills.

Key areas of variability in training programs between states include:

-

(i)

Proportion of course content devoted to intervention/rehabilitation, compared to diagnostic assessment and knowledge regarding various conditions affecting brain functioning;

-

(ii)

Coursework content and formal supervised practice or skill development in counselling and psychological therapies (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, motivational interviewing, mindfulness, relaxation techniques).

-

(iii)

Availability of clinical or research placements/internships where neuropsychological interventions are regularly implemented, in order to gain practical experience and develop skills in a supervised environment. Most placements tend to focus on developing and practising skills in diagnostic assessment, clinical formulation/interpretation, and communication of assessment outcomes, e.g. via reports and/or feedback.

-

(iv)

Incorporation of opportunities to conduct or co-facilitate interventions within university training clinics. Students report positive feedback on these experiences when they are offered, describing increased skills and confidence in delivering interventions and an increased interest in conducting interventions in future (Pike et al., 2020).

-

(v)

The inclusion of assessment tasks requiring students to demonstrate they can plan, implement, and evaluate neuropsychological interventions with real or simulated cases.

More consistent provision and evaluation of these training activities and models have the potential to enhance the breadth and depth of competencies in neuropsychological interventions among graduates of clinical neuropsychology training programs.

Ongoing training and upskilling beyond university training programs is necessary to ensure a skilled workforce, as reflected in the professional development requirements associated with psychology registration. Experienced clinicians may not have received comprehensive training or practice in delivering neuropsychological interventions and may have worked in settings where their role primarily involves assessment. Workshops, short courses, and clinical supervision may be beneficial for skill development and refinement in intervention skills and techniques throughout all career stages (Wong et al., 2021b, 2020).

While the structure of neuropsychology training differs around the world, these principles of ensuring neuropsychological intervention competencies, which have been clearly and comprehensively defined and are taught and assessed both during postgraduate training and beyond, apply internationally. Agreement on which competencies are essential for effective practice would facilitate international consistency in training and practice of neuropsychological interventions.

Section 3: Evidence Base and Clinical Utility of Neuropsychological Interventions in Adults and Older Adults

In this section, we summarise key evidence and considerations for neuropsychological interventions in three main cohorts: (i) acquired brain conditions including traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, and multiple sclerosis (MS); (ii) psychiatric disorders; and (iii) older adults including healthy older adults, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. In the Appendices, we summarise the evidence based on existing systematic reviews and guidelines in separate tables (labelled with ‘a’ and ‘b’ throughout):

-

(a)

The interventions for each population for which there is sound evidence of impact at the level of activity/participation (for practical guidance on application of the WHO-ICF, see World Health Organization, 2013).

-

(b)

Interventions for which sound evidence of impact on activity/participation is still required (i.e. evidence is at the level of impairment only OR there is only limited evidence of impact on activity/participation).

The evidence presented in the tables in the Appendices represents meta-analytic-level evidence where available or otherwise the highest level of evidence possible. We note the evidence will continue to build and expand, and we encourage clinicians to use the framework presented in the tables (i.e. classifying according to whether evidence of impact is at the level of activity/participation) to guide their clinical decision-making into the future.

General Considerations

Across the three diagnostic cohorts, there is evidence that several types of neuropsychological interventions, particularly cognitive rehabilitation focused on personally meaningful goals and drawing on strategy-based training, can improve everyday function. There is limited support for functional or day-to-day benefits of computerised cognitive training as a standalone intervention when it is not combined with other (preferably personalised) support to apply strategies in everyday situations. Given that many computerised ‘brain training’ programs can require expensive subscriptions, clinicians should carefully seek high-level evidence of their efficacy and everyday impact before recommending them to clients. Brain training needs to be adaptive, intensive, and extensive for optimal restorative benefits. The SharpBrains checklist (Sharpbrains, n.d.) contains a good set of questions for consumers to ask themselves (or explore with their clinician) before embarking on a brain training program. Integrating health and lifestyle improvements (e.g. exercise, nutrition, and sleep) into neuropsychological interventions shows promise and clinical neuropsychologists are encouraged to incorporate evidence-based lifestyle recommendations in their feedback to clients. Group-based interventions also appear to have numerous benefits, including connection with others with similar lived experience. However, the ability to tailor interventions to individuals is a helpful advantage of those delivered one-on-one, and this is often necessary especially for people with complex needs.

There is some evidence that complex interventions that combine cognitive and psychological elements may be more effective in improving activity, participation and quality of life than treating impairments in isolation (Davies et al., 2023). The broader evidence for other combined or multicomponent interventions (e.g. combining behavioural with cognitive and/or psychological elements; combining restorative and compensatory cognitive training approaches; combining cognitive rehabilitation with physical or pharmacological interventions) is still developing and needs to be systematically evaluated across cohorts and intervention types. When considering whether to combine empirically supported intervention ‘modules’ into bespoke multicomponent interventions for individual clients, clinicians should consider not only the evidence for each component, but (i) also whether each component is justified by the case formulation, and (ii) the proposed underlying mechanism of action for each component, to ensure the combination of components has a solid rationale. The need for further research to help guide this kind of clinical decision-making is further detailed in the ‘Conclusions and Future Directions’ section.

Neuropsychological Assessment Feedback

Often overlooked as a form of neuropsychological intervention, neuropsychological assessment feedback to the patient and caregivers can be conceptualised as its own brief, therapeutic, psychoeducational, single-session intervention. We cover it briefly here as an intervention that applies equally to all three diagnostic cohorts. Models or frameworks for delivering feedback have been proposed, but not yet thoroughly evaluated (Gorske & Smith, 2009; Postal & Armstrong, 2013). Evidence supporting the benefits of neuropsychological feedback is currently based primarily on consumer satisfaction surveys (Gruters et al., 2021). In one of the most recent surveys, neuropsychological assessment feedback was found to be followed by improvements in the patients’ quality of life, knowledge about their condition, and ability to cope (Rosado et al., 2018). A prospective follow-up study (Lanca et al., 2020) subsequently replicated and extended these findings, adding reduced psychiatric and cognitive symptoms, and increased self-efficacy and confidence in achieving goals to the list of benefits following feedback.

These findings contrast with concerns that a proportion of patients in these survey studies reported negative outcome following feedback (Longley et al., 2022), and that providing diagnosis-focused feedback (e.g. confirming likely dementia) can be harmful to some patients if not delivered sensitively. Reassuringly, a recent RCT with cross-over, in MS, showed no adverse psychological effects one week after feedback, despite most patients receiving ‘bad news’, and significant improvements in mood, self-efficacy, and perceived everyday cognitive functioning 1 month later (Longley et al., 2022). The authors outlined a list of feedback components they thought might have been psychologically protective for those participants receiving the bad news. We are also aware of upcoming trials of neuropsychological assessment and feedback as an intervention in dementia/mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and stroke. Collecting evidence for the therapeutic impact of feedback, as well as the most effective model of delivery, is an urgent and important priority for our field. It is often the first part of the neuropsychological intervention process and can be critical for further engagement. With supporting evidence, it could arguably be a primary neuropsychological intervention that all clinical neuropsychologists should consider delivering as a matter of routine practice.

Common Neuropsychological Interventions

As many interventions have been trialled in all three of the populations discussed in this section, we have included a list of commonly used neuropsychological interventions that appear throughout the summaries and tables, briefly describing the nature and key features of each intervention. We note that this is not an exhaustive list of all existing neuropsychological interventions, and that the interventions listed here are not mutually exclusive. Where interventions have a high degree of overlap or have more than one label, we have indicated this in the table.

Adapted psychological therapies These aim to improve mental health and wellbeing in people with neuropsychological conditions and include adaptations to ensure therapy is suitable for people with cognitive impairment and/or neurological conditions | |

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) — adapted for cognitive impairment | A psychological therapy that aims to change how an individual relates to distress and promotes engaging in behaviours consistent with the individual’s values. ACT components include the following: present moment awareness, acceptance, defusion, self-as-context, committed action, and values. Adaptations to ACT include reducing the more abstract components, and focusing on value-consistent behaviours |

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) — adapted for brain injury (CBT-ABI) | A psychological therapy that aims to identify and change unhelpful patterns of thinking and behaviour that contribute to the presenting issues. CBT components include the following: cognitive restructuring, behavioural activation, relaxation techniques, structured problem solving, graded exposure, and relapse prevention. Adaptations include use of repetition, simplified explanations and handouts, scaffolded cognitive restructuring, and greater emphasis on behavioural components |

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) — adapted for brain conditions | A psychological therapy promoting mental and emotional wellbeing by cultivating self-compassion. When applied to people with brain conditions, the focus of the self-compassion is on the impact of neuropsychological impairments |

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy | Combines cognitive behavioural techniques and mindfulness strategies to regulate thoughts and emotions and reduce distress related to the brain condition |

Behavioural strategies These aim to support individuals and families with managing behaviours of concern related to their brain condition | |

Anger management training | The use of cognitive behavioural techniques targeted at anger management concerns |

Environmental modification | Aimed at reducing the impact of cognitive impairment or challenging behaviours by modifying the environment around a person to provide cognitive aids and/or remove potential triggers for challenging behaviour |

Positive behaviour support (PBS) | A client-centred holistic approach that teaches new skills to replace behaviours that are challenging and optimise quality of life. By identifying and changing the antecedents and consequences of behaviours of concern, a positive behaviour support plan is developed with a focus on developing new skills that enable the person to do things that are meaningful to them |

Social skills training | A form of behavioural therapy that covers a suite of interventions to improve social skills. Techniques include education and modelling appropriate behaviour, role play, corrective feedback, and positive reinforcement |

Cognitive strategies — compensatory These aim to minimise the impact of cognitive impairment on daily functioning through the use of aids or strategies to reduce cognitive load or perform affected tasks in a different way. Strategies include internal (mental) strategies, external aids (using tools in the environment), and systematic instructional approaches such as errorless learning. These are tailored to the cognitive strengths and weaknesses and personalised goals of the individual. Also can be termed ‘cognitive rehabilitation’ | |

Attention process training (APT) | A range of tasks designed to exercise specific types of attention (sustained, selective, alternating, divided), administered in a hierarchical fashion (i.e. become more demanding) |

Attention retraining | A range of exercises and compensatory strategies aimed at improving functional attentional abilities |

Chaining | Involves breaking a task or procedure down into discrete steps. Each step is trained using prompts (verbal, visual, modelling), with gradual fading of prompts as the client becomes independent. Each step can be used as a prompt for the next step, so that the behaviours are ‘chained’ together. Both forwards and backwards chaining can be used. Training of each step often draws on an ‘errorless learning’ approach (see below) |

Errorless learning | A method for systematically learning and remembering a novel task or skill. Tasks are broken down into small steps and the person receives immediate corrective feedback for each step to prevent them making a mistake (i.e. not trial and error learning). Helpful for those with intact procedural memory but impaired declarative memory |

Goal management training | Aims to improve a person’s ability to complete purposeful everyday activities, usually in the context of executive dysfunction. Teaches a sequence of steps to raise awareness of attentional lapses, identify any problems, develop alternative solutions, monitor implementation, and check for errors |

Group-based memory skills training | Group-based programs, usually of fixed length, that train use of internal and external memory strategies |

Gesture training | Developing non-verbal communication skills to enhance communication for people with speech difficulties |

Interpersonal process recall (IPR) | Aims to improve communication skills by using video playbacks of different social interactions between client and clinician. Clients are encouraged to provide self-feedback, in addition to the clinician’s feedback |

Mental imagery | An internal compensatory strategy aimed at improving spatial neglect by asking the person to imagine in detail moving their body on the neglected side or attending to visual information on the neglected side |

Metacognitive strategy training | Aims to improve performance of purposeful tasks through the use of various strategies to improve self-awareness, self-monitoring and self-correction of errors. Example strategies are self-talk, self-reflection and agendas to track progress |

Modified story memory technique (mSMT) | Aims to improve episodic memory through the use of context and imagery |

Music mnemonics | Aims to improve memory and recall by putting information to melodies |

Retrieval practice | Aims to improve learning and memory by deliberately recalling information and actively ‘bringing it to mind’ repeatedly, as opposed to passively re-reading or listening to the information |

Self-generation | Strategy to improve learning and memory in which people are given information with sections missing, and must generate answers themselves to fill the gaps (as opposed to being provided with all the information upfront) |

Spaced retrieval (SR) | Aims to improve recall of information by eliciting active recall of newly learned information over progressively longer intervals of time |

Strategy-based cognitive training (SCT) | Encourages the use of both internal techniques (e.g. visual imagery, categorisation, structured heuristics for problem-solving) and external techniques (e.g. calendars, environmental cues) to strengthen relevant cognitive functions and adapt to areas of weakness or decline by recruiting additional cognitive networks. SCT therefore involves active teaching, modelling and guidance in adaptive techniques by a facilitator. Many strategy-based approaches also incorporate psychoeducation regarding cognitive processes (e.g. encoding), which is often used to contextualise the strategies |

Time pressure management | Consists of a set of compensatory cognitive strategies, deployed using a systematic process, to allow for mental slowness during real-life tasks by either preventing or managing time pressure |

Video feedback | Direct corrective feedback may be used with people with impaired self-awareness. Approaches include involvement in contextualised occupationally-based activities, training to anticipate obstacles to optimise performance, verbal/audio-visual and experiential feedback, self-monitoring, and self-evaluation techniques |

Visual imagery | An internal compensatory strategy aimed at improving memory for specific information by visualising it in rich detail |

Visual scanning training | Encouraging people to actively pay attention (self-cue) to stimuli on a neglected side to improve visual scanning behaviour |

Cognitive strategies — restorative Aim to recover function in certain cognitive domains affected by brain injury by repetitive skill practice in the affected domain. Tasks are usually administered in a graded way, building on specific processes to become more complex | |

Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) — includes computerised cognitive training (CCT) | Involves a broad range of learning-based interventions aimed at improving or restoring cognition broadly or in targeted domains. CRT typically involves repetitive drill-and-practice training exercises. CCT is the most common form of CRT, and involves specific computerised cognitive training programs aimed at improving particular aspects of cognition, commonly working memory. The software provides a structure in which to practice tasks, and is usually able to adapt task difficulty to suit ability. This can be paired with support from a clinician around strategies for improving task performance and how the training tasks and strategies are relevant and may be applied in daily life |

Dual task training | Aimed at improving impaired executive functioning by practicing performing two competing tasks at once. Tasks can be any combination of cognitive and/or motor in nature |

Eye patching | In the context of visual neglect, eye patching is used to encourage attention towards the neglected visual field by covering the intact visual field |

Gist reasoning | Gist reasoning is the ability to abstract and generalise meaning from complex information. Cognitive training based on this top-down reasoning approach (as opposed to ‘bottom-up’ rote learning) aims to improve long term learning and fact recall |

Mirror therapy | A body awareness intervention used in the rehabilitation of spatial neglect, focusing on proprioception and awareness of the body in space in relation to midline. A mirror is placed in the midsagittal plane to reflect the movements of one limb superimposed on the other limb |

Perceptual interventions (e.g. sensory stimulation) | Aims to recover perceptual deficits. For example, sensory stimulation aims to stimulate visual sensation, such as shape recognition tasks |

Strategic Memory Advanced Reasoning Training (SMART) | Aims to train functionally relevant complex reasoning abilities using a variety of control strategies (e.g. strategic attention learning to block out less relevant details) |

Other | |

Cognitive stimulation therapy | Promotes active cognitive stimulation and socialising, usually for people with mild to moderate dementia |

Feedback | The provision of neuropsychological assessment feedback after testing is completed, usually at an additional session with the patient and/or family members. Information covered usually includes the patient’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses, psychoeducation on the likely causes for their presenting concerns (including diagnostic/biopsychosocial formulation), and management recommendations |

Multimodal (or multicomponent) interventions | Interventions that draw on multiple components, often incorporating strategy-based CT, CCT, cognitive stimulation and psychoeducation; or combining cognitive, psychological and/or behavioural strategies. May also combine neuropsychological intervention with other forms of intervention, e.g. physical exercise, dietary supplementation, and medication |

Psychoeducation | Refers to active communication and exchange of information to improve understanding about psychological, cognitive and/or behavioural issues associated with a brain or mental health condition. Information about the nature and causes of symptoms and how to manage or treat them is typically included. Can be delivered in individual or group formats |

Social cognitive training | Includes a broad range of training exercises aimed at improving social cognition in everyday life. Social cognitive training typically involves engaging in therapist-facilitated exercises, and practice in applying the skills learnt to everyday social situations. These can include drill-and-practice exercises, strategy games, heuristic practice, mimicry, and role plays |

Virtual reality training (VR training) | The use of virtual reality technology to aid motor and cognitive rehabilitation, usually by simulating scenarios in which a person performs a daily task such as cooking in a kitchen or going to the supermarket |

The Evidence for Neuropsychological Interventions in Acquired Brain Injury and Illness

The following section summarises evidence for neuropsychological interventions in acquired brain injury and illness (ABI), with a particular focus on traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, and multiple sclerosis (MS). While the ABI umbrella includes a range of other diagnostic groups including brain tumour, hypoxic brain injury, encephalitis, and epilepsy, the available evidence on interventions with these groups is more limited. However, research in this field often includes mixed samples, and many of the same principles apply across the various ABI types.

In some reviews, MS is placed in a group with other progressive neurocognitive conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, where the focus of interventions might be to preserve cognitive functioning or delay the functional impact of neurobiological changes (Sumowski, 2015). However, in the context of our focus on activity and participation outcomes in this clinical guidance paper, intervention research on MS fits more readily with other forms of ABI, for whom stage of life and personal goals tend to be similar (e.g. sustaining paid employment by learning to retain new work instructions, or contributing to parenting via improved concentration).

Much of the existing evidence on neuropsychological rehabilitation interventions has been collected with ABI cohorts, particularly TBI. There is a wide range of effective cognitive, psychological, and behavioural interventions in these groups, plus a large selection of emerging interventions. The literature points to the importance of person-centred, goal-directed, tailored interventions that are meaningfully embedded in the person’s life roles and valued activities.

Clinical neuropsychologists are central members of multidisciplinary teams that support clients in their rehabilitation post-TBI. However, the healthcare system supporting survivors of stroke has evolved differently, particularly given the lack of insurance systems funding rehabilitation prior to the onset of the NDIS. Australian audit data (Stroke Foundation, 2020) found that over 50% of stroke services reported no access to a neuropsychologist. This is despite the clinical guidelines for stroke management (Stroke Foundation, 2017) supporting the need for intervention across multiple cognitive, emotional, and behavioural domains. There is an urgent need for support for a greater neuropsychology workforce in stroke services, to optimise outcomes for survivors of stroke.

Likewise, the neuropsychology workforce supporting people living with MS is not centralised in specific MS services and instead tends to be mostly private practitioners. People with MS without sufficient personal funds cannot access these sorts of services. This is despite a number of recent, clinically-focused overviews of the state of the science in this area (Brochet, 2021; Chen et al., 2021; DeLuca et al., 2020) which have described the evidence supporting a wide range of neuropsychological interventions in MS. For instance, DeLuca and colleagues (2020) concluded that ‘… cognitive rehabilitation has shown consistent beneficial effects in patients with MS and currently represents the best approach for treating MS-related cognitive impairment’. Consequently, there is also a urgent need for support for greater access to neuropsychology workforce in MS services (Longley, 2022).

Key Considerations

-

The cognitive effects of TBI, stroke, and MS vary considerably from one individual to the next but may include impairments of attention and speed of information processing, memory, executive function, communication (including changes in social cognitive functions), and visuo-spatial function. Key principles that apply to addressing cognitive impairments in acquired conditions include the need to identify the individual’s pre-injury functioning and assessing the impact of problems in everyday contexts.

-

For conditions that fluctuate or deteriorate rather than recover or improve, such as MS, there are additional psychological challenges for both the person and their caregivers, such as learning to live with an unpredictable combination of symptoms over time and an uncertain future. Some may also have to find ways of coping with distressing transitions (e.g. moving from a relapsing-remitting phase of MS to a secondary progressive phase, or moving from being independently ambulant with a walking aid to needing to use a wheelchair to get around). It should be noted that psychological therapies for depression, anxiety, and adjustment in MS have not been reviewed in this clinical guidance paper, since neuropsychologists generally do not deliver these interventions in Australia. However, there is a moderate and accumulating evidence base supporting therapies such as cognitive behaviour therapy in people with MS to treat depression (Khan & Amatya, 2017), stress and distress (Taylor et al., 2020), and fatigue (Harrison et al., 2021).

-

Many TBI survivors are young and still in the process of establishing independence from parental support, studying or learning a vocation, and establishing important personal and social relationships. The inability to attain these important life goals can have devastating effects on their self-esteem and emotional state. Therefore, proactively addressing the cognitive, behavioural, social, and psychological barriers to attaining these goals is imperative. Their needs will change across the lifespan, so a long-term perspective is important.

-

Due to the older demographic of many stroke survivors, it is important to advocate for access to rehabilitation to address goals such as independent living, work, caring, and leisure-related life roles. Compared to people who sustain an ABI in early adulthood, many older stroke survivors have established work and life skills and other resources that can be drawn upon to support their engagement in interventions. However, survivors are at an increased risk of developing dementia, particularly vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or mixed vascular/AD (Savva & Stephan, 2010). Thus, ongoing monitoring of cognitive functioning is recommended to ensure the most appropriate neuropsychological interventions are provided over time.

-

Multiple systematic reviews have highlighted a lack of high-quality studies investigating the efficacy of psychological therapies such as CBT in ABI (TBI/stroke) populations, which constrains the ability to provide firm recommendations (Fann et al., 2009; Gertler et al., 2015; Guillamondegui et al., 2011). Evidence for psychological therapies should be considered preliminary and clinicians are encouraged to monitor treatment progress to establish its efficacy in individuals (Gertler et al., 2015). In the absence of evidence for ABI specifically, psychological intervention is recommended if efficacy is demonstrated in the general population. However, psychological therapies such as CBT require modification for clients with ABI due to their cognitive impairments (Gallagher et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2019b).

-

There is limited research evidence regarding the efficacy of antecedent or traditional consequence-based behaviour modification approaches to addressing behaviours of concern following ABI (including TBI, stroke, and MS). There is growing clinician support for contextualised approaches that modify the antecedents to behaviour problems based on consideration of precipitating factors that maintain negative behaviour, relating to the person, their injury-related cognitive impairments, and the environment, as well as factors that facilitate positive behaviour. Such approaches aim to assist individuals to self-manage behaviour, promote positive lifestyle changes, and increase community functioning and positive family environments. Personally meaningful activities and identified valued outcomes provide a basis for re-engagement with post-acute life (Ylvisaker et al., 2003). Positive, well-rehearsed routines are encouraged, to promote structure in and engagement with daily living. Feedback and consequences must be context sensitive and meaningful, and behavioural supports positive and proactive (Ylvisaker et al., 2007). Importantly, existing family members, friends, and carers are included in the adoption and integration of management techniques, and feedback is provided in the individual’s own environment, to encourage community-based and integrated supports (Ylvisaker et al., 2007). The integration of goal setting and community and clinical supports is important to achieving gains. An RCT of positive behaviour support (PBS) has shown that this approach can be effective in reducing challenging behaviours, with gains maintained over at least eight months post-intervention, in increasing the self-efficacy of close others in managing these behaviours (Ponsford et al., 2022), as well as attaining meaningful individual goals (Gould et al., 2021). A clinic has now been established and training resources for clinicians are under development using a co-design approach (Gould et al., 2019).

-

For individuals with severe cognitive and behavioural difficulties following ABI, family members are an integral part of the support team. Recent evidence adopting a family-directed intervention approach shows promise in supporting the capability of family members to provide behaviour support (Fisher et al., 2021). The abovementioned recent RCT showed that a positive behaviour support intervention that actively involved close others including family (PBS-PLUS) resulted in a significant increase in their self-efficacy in managing challenging behaviours (Ponsford et al., 2022). However, much more research is needed.

-

ABI is more common in indigenous Australians than in non-indigenous Australians; however, there is limited research evaluating culturally appropriate rehabilitation, and the research is particularly sparse when it comes to neuropsychological interventions (Lakhani et al., 2017). This is an urgent area for future research.

-

The tables in this section have been separated into two Appendices, such that TBI, stroke, and other non-degenerative ABIs are included in Appendix 1 (Tables 1 and 2), and MS is included in Appendix 2 (Tables 3 and 4). This is because the MS literature is different in nature and scope, partly because MS is most commonly progressive, and much of the neuropsychological intervention research in MS has focused on specific techniques rather than the complex holistic interventions prominent in the TBI/stroke literature.

The evidence for the interventions presented in these tables is large and rapidly expanding. A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs or quasi-RCTs provide low-moderate evidence mostly at the impairment level (e.g. as measured by objective cognitive performance), but there is also growing evidence for positive activity, participation, and quality of life outcomes. There are numerous individual studies showing some benefits on these broader outcomes, but these findings may not yet have been replicated, so they have not been listed as providing sufficient evidence at the level of participation to warrant inclusion in Tables 1 and 2 (the literature on CBT for ABI is an example of this).

See Appendix 1 for a summary of the evidence in TBI, stroke and non-degenerative ABI (Tables 1 and 2). See Appendix 2 for a summary of the evidence in MS (Tables 3 and 4).