Abstract

We investigate the syntax of the hitherto understudied phenomenon of first conjunct clitic doubling, with reference to Modern Greek. We argue that it provides crucial evidence against movement-based approaches to clitic doubling, which would incorrectly rule out first conjunct clitic doubling as a violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint. This argument against movement is complemented by evidence from binding, showing that doubled DPs consistently occupy their base positions. The Greek data instead favor an account based purely on feature transmission via Agree. We develop an Agree-based analysis of the Greek facts, and show that existing evidence for movement in Greek clitic doubling (Weak Crossover alleviation, suspension of intervention effects) can be insightfully reanalyzed. The alleviation of Weak Crossover effects receives a more straightforward account compared to movement-based approaches, in that it can be subsumed under the general mitigating effects of information structure (givenness, topicality); the intervention pattern follows once the activity of a DP is related to the involvement of its phi-features in Agree operations; and the distribution of clitic doubling is implemented by means of a licensing approach, assimilating clitic doubling to differential object marking. Finally, we address two morphological aspects of clitic doubling that are often taken to be challenging for an Agree-based account, namely, the syncretism between determiners and clitics, and tense invariance. We show that, upon closer inspection, the former is no less challenging for movement approaches, while the latter cannot be considered a reliable diagnostic to tease apart agreement and clitic doubling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Two phenomena that have separately received much attention in syntactic theory are coordination and clitic doubling (henceforth CLD). The former phenomenon has been the subject of intense scrutiny, with the structure of coordinate phrases often being probed through the lens of how their constituent parts may be targeted for agreement.

The latter, CLD, like other doubling constructions, poses significant challenges for theta- and case-theory in that two elements seem to occupy the same argument slot. Several analyses for CLD have been proposed that implement the doubling differently, often on the basis of different languages; but mounting convincing empirical arguments for or against a given approach for a given language has proven difficult.

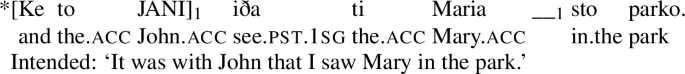

In this paper, we show that investigating CLD in the context of coordination can shed new light on its underlying syntax. We take as our starting point a largely novel observation,Footnote 1 namely, the phenomenon of first conjunct clitic doubling (henceforth FC CLD) in standard Modern Greek (MG).

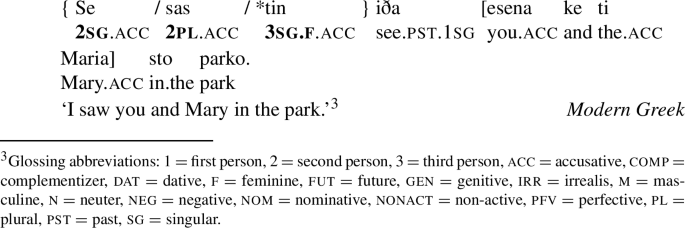

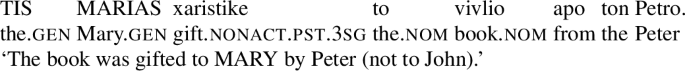

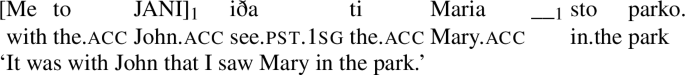

FC CLD is illustrated in (1) below. There are two ways of doubling the coordinated object ‘you and Mary’: firstly, the resolved features of the entire coordination can be targeted for doubling, yielding the second plural clitic sas; we will refer to this option as resolved doubling. Interestingly, however, doubling can also target just the first conjunct, giving rise to the second singular clitic se, an instance of FC CLD. Importantly, only the first conjunct can be targeted in this way: doubling of the second conjunct, here by means of the third singular feminine clitic tin, is ungrammatical.Footnote 2

-

(1)

In this paper, we explore the implications of FC CLD for the syntax of clitic doubling in Greek more generally; in particular, we show that FC CLD provides evidence in favor of a pure Agree-based analysis of clitic doubling in this language.

Since our crucial data comes from Greek, the scope of our main claims is circumscribed to this language, and does not necessarily extend to other doubling languages. Our goal here is to provide the best possible analysis of the pattern within a single language; it is very well possible that when applied to other languages, our diagnostics will suggest a different treatment of clitic doubling in that language. We thus stress that we do not wish to claim that what is laid out below is the only possible approach to clitic doubling, nor that it should be understood as the theory of clitic doubling.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the basic data to be accounted for and provides evidence that FC CLD cannot be reanalyzed as resulting from clausal ellipsis; Sect. 3 then examines the implications of FC CLD for theories of clitic doubling and concludes that it furnishes evidence against movement-based approaches to CLD since they predict a violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint. Instead, FC CLD is argued to favor approaches solely based on Agree. Section 4 discusses phenomena taken to support movement in CLD from the previous literature and shows that the data can be accommodated within an Agree-based account. Section 5 addresses morphological aspects of clitic doubling. Section 6 concludes.

2 Data

We begin this section by providing short background points for our claim, focussing on Greek CLD and First Conjunct Agreement (FCA). We continue by (re)introducing FC CLD, and conclude the section by fine-tuning the empirical details of our claim, ruling out alternative parses of our coordination examples.

2.1 Background

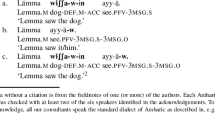

Our attention in this paper is devoted entirely to clitic doubling as in (2a), where the doubled DP ton Jorɣo occupies an argument position (for a representative treatment of CLD in Greek, see Anagnostopoulou 2003). Clitic doubling is to be distinguished from clitic-left dislocation (CLLD) (2b), where the same DP occupies a higher left-peripheral position (see Angelopoulos and Sportiche 2021 for recent discussion).

-

(2)

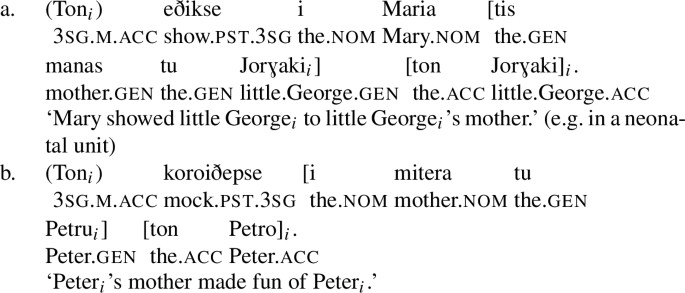

In Greek, only direct and indirect objects can be clitic doubled while PPs and subjects cannot (Greek being a pro-drop language, there are no subject clitics). In line with the findings of much recent work, we assume that, in CLD, the doubled DP occupies an argument position and is not dislocated. There is much evidence against a dislocation analysis from Greek and beyond, based on the doubling of ECM subjects (Angelopoulos 2019: 3; see also our ex. in (28) and (37) below), word order and reconstruction effects (Angelopoulos 2019), case connectivity effects (Harizanov 2014: 1045ff.), and possessor extraction from doubled DPs (Harizanov 2014: 1045ff.). The binding data discussed in Sect. 3.3 below further support the conclusion that doubled objects remain in situ.Footnote 3

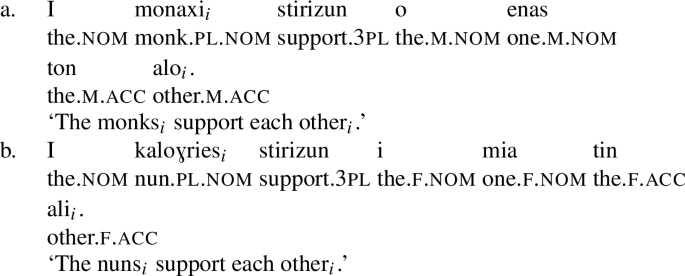

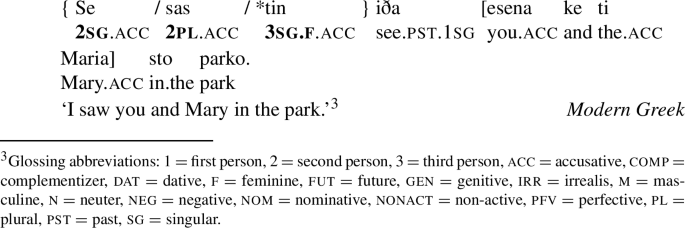

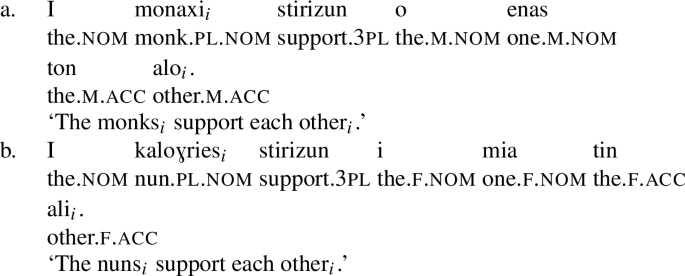

A second background point of interest concerns the fact that Modern Greek shows first conjunct agreement (FCA). When the subject is a coordinate phrase, the Greek finite verb can index either the resolved features of the coordination, or the features of the first conjunct; it can never agree with the second conjunct. This situation is exemplified in (3a), where a coordination of second and third singular triggers either second singular or second plural agreement, but not third singular agreement. In (3b), the order of conjuncts has been flipped, with consequences for the agreement possibilities: since the first conjunct is now third singular, third singular agreement on the finite verb becomes possible.Footnote 4

-

(3)

FCA is only possible with postverbal subjects; if we were to change (3) to involve preverbal subjects, only resolved agreement would be possible. Preverbal subjects in Greek are sometimes taken to be left-dislocated elements (Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1998), but their exact status is far from settled (see also fn. 16 below). To ensure the availability of FCA, and to avoid possible complications regarding the position of preverbal subjects, we consistently use postverbal subjects in this paper. We focus chiefly on VSO, a readily available order in Greek clauses; assuming that postverbal subjects in VSO occupy Spec,vP (see Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1998: 496), we will use them as a diagnostic for the edge of vP.

2.2 New data: FC CLD

Alongside first conjunct agreement, Greek also allows first conjunct clitic doubling, as discussed with reference to (1) above, repeated here as (4a). (4b) shows that, just as in FCA, switching the order of conjuncts yields new FC CLD possibilities.

-

(4)

Similar to FCA, FC CLD is only possible with postverbal objects and not with preposed/CLLD-ed objects, a fact discussed in detail in Paparounas and Salzmann (2023: Sect. 4.3).

In Modern Greek, person and number can participate in FCA, while person, number and gender can participate in FC CLD (modulo the variation mentioned in fn. 5). Person resolution proceeds according to the hierarchy 1st>2nd>3rd person, and always leads to plural agreement/doubling. Gender resolution patterns in cases of conflicting gender specifications are complex (see Adamson and Anagnostopoulou To appear for a recent approach to resolution in coordination in Greek); in our examples, resolution of gender will generally lead to masculine.

In what follows, we argue that first conjunct agreement (3) and first conjunct clitic doubling (4) are two sides of the same coin: like agreement, first conjunct clitic doubling in Greek is derived by means of the operation Agree. Crucially, FC CLD suggests that this Agree operation is not accompanied by movement.

2.3 Ensuring FCA/FC CLD

Before exploring the theoretical implications of the phenomenon, we will first show that the data we have introduced as FCA/FC CLD indeed represent these phenomena, that is, that they involve DP coordination where agreement targets the first conjunct. This will involve fine-tuning the relevant empirical details. More specifically, we will show in this section that a) the element ke is a true coordinator and not a comitative preposition, and b) the crucial examples do not involve a clausal coordination-cum-ellipsis parse.

2.3.1 Against a comitative analysis

Crucial in what follows is that the element ke, which we gloss as ‘and,’ is actually a coordinator, instead of, for example, a (comitative) preposition. That this is indeed the case is easy to diagnose by means of fronting: unlike bona fide comitative PPs (5), ke+DP does not front under focus (6):

-

(5)

-

(6)

2.3.2 Ruling out clausal coordination

A central aspect of our argument is that our examples involve true DP coordination, as opposed to a different underlying structure that resembles coordination on the surface. Illustrating with English for convenience, we must ensure that FCA examples such as those examined above have the structure in (7):

-

(7)

. arrived [you and Mary]

That we are dealing with (7) is not to be taken for granted; it could be the case that the same strings are generated by structures that involve coordination of larger constituents followed by ellipsis. (8) illustrates these competing possibilities. (8a) involves coordination at the T′ level followed by silencing of the verb in the second conjunct; in (8b), two TPs have been coordinated, with a DP vacating the second conjunct and thereby escaping ellipsis, before the remnant TP is deleted. Following standard terminology, we will refer to the parse in (8a) as gapping, and to (8b) as stripping.

-

(8)

These clausal coordination-plus-ellipsis parses must also be eliminated for the case of FC CLD. Just as in FCA, we must ensure that FC CLD has the structure of true DP coordination as in (9), as opposed to gapping or stripping in (10):

-

(9)

. I

-saw [you and Mary]

-saw [you and Mary]

-

(10)

Below, we provide diagnostics ensuring that DP coordination is indeed at play in our examples (although such ellipsis parses are, in principle, possible in the language as well). We begin with and focus on FC CLD, and show that there are grammatical FC CLD examples that cannot be generated by a stripping/gapping parse involving coordination of verbal constituents, and thus that FC CLD must be possible with DP coordination.

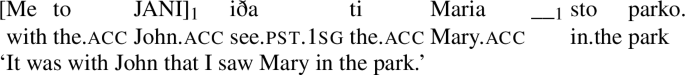

For a first argument in favor of the possibility of DP coordination with FC CLD, consider (11).

-

(11)

The natural interpretation of (11) is that no entity has won both contests within some specified interval; this reading is reinforced by the parenthesized material at the end of this example (note that Greek is a negative concord language, hence the example obligatorily includes sentential negation alongside the negative subject). A stripping parse of (11), while possible in principle, predicts a wholly different reading: if (11) were derived from underlying ‘Nobody has ever won the world championship and nobody has ever won the Olympic games,’ (11) should only have the reading whereby nobody ever won either contest, a reading that happens to be obviously false in our world.

Moreover, consider (12).

-

(12)

The property of (12) of interest for our purposes is the negative subject nobody. Importantly, (12) is grammatical on an interpretation where a single seeing event is negated: more specifically, it is true in a context where someone saw the referent of you, and someone saw Mary, but nobody saw the referent of you and Mary together.

This reading cannot be accommodated on a stripping parse, which would have the general shape schematized in (13) and crucially includes the negative quantifier in both conjuncts (nothing here hinges on whether Mary would have to vacate a constituent undergoing deletion, or whether deletion is instead distributed):

-

(13)

(13) supplies two conjoined verbal constituents, each containing one seeing event which is negated. In other words, if (13) were the only way to derive (12), (12) should only be true in situations where neither the referent of you nor Mary were individually seen. Importantly, however, (12) also has a reading whereby no-one saw the group formed by the referent of you and Mary, but individual seeing events did take place. As such, DP coordination must be available for (12), even if the parse in (13) is independently possible. The examples in (11) and (12) are also not amenable to a gapping parse: given that the negative subject quantifier is postverbal, it cannot have scope over the coordination if T′-coordination is involved.

A second robust diagnostic ruling out clausal co-ordination involves collective verbs. In (14), FC CLD targets the first conjunct y’all; importantly, the sentence accommodates a monoeventive reading whereby addressee and speaker were gathered in the principal’s office in a single gathering event, suggesting that the underlying structure does not necessarily supply a bieventive base. Crucially, here an ellipsis base would not just yield the wrong number of events, but would instead be ungrammatical altogether: as (15) shows, gather is ungrammatical with a single, singular object, suggesting that (14) cannot be derived by TP-level coordination and gapping/stripping.Footnote 5

-

(14)

-

(15)

Collective verbs can also provide an argument against stripping/gapping for the case of FCA, at least for some speakers (see fn. 6). For the relevant group of speakers, (16) is grammatical but (17) is not, suggesting that (16) must be derivable by means of DP coordination.

-

(16)

-

(17)

In conclusion, then, FC CLD cannot be reanalyzed as resulting from clausal coordination + ellipsis. Rather, it obtains in the presence of DP-coordination.Footnote 6

3 Implications for theories of CLD

In this section, we first survey (families of) theories of CLD, before arguing that only one of them is compatible with our FC CLD data, namely, the family of pure Agree-based approaches. Movement-based approaches fail because they would incur a violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint in the derivation of FC CLD. Finally, we provide new arguments against movement-based approaches, focussing on data from binding Conditions A and C.

3.1 Theories of clitic doubling

On the surface, clitic doubling is a puzzle for theories of Case and thematic interpretation. The structure contains two elements, namely the clitic and the doubled DP, but presumably only one locus of thematic interpretation and Case assignment. Of the two elements, then, one must be assigned the role of the primary argument, with the other being licensed in a different way. To articulate a theory of clitic doubling, then, is to specify what the mechanism is that gives rise to doubling (see Anagnostopoulou 2017a for a recent overview).

In this section, we briefly summarize the three major approaches to clitic doubling, focusing less on details of technical implementation and more on the question of how the presence of the clitic is derived in each account (we will thus omit verb movement to T and optional externalization of the subject to Spec,TP in our diagrams). Of crucial interest here is whether a given account involves movement, and, if so, what type of movement is assumed. As we will argue, the availability of FC CLD in Greek is only compatible with approaches that do not postulate movement of either the doubled DP or the clitic.

Throughout, we illustrate the different analyses by providing (simplified) trees for the simple clitic doubling example in (18).

-

(18)

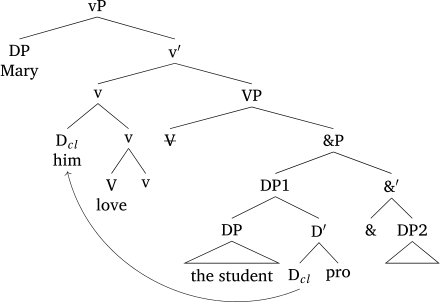

In the family of theories known as the big-DP approach, the clitic and the doubled DP are taken to originate in the same DP constituent. The underlying intuition is that anaphoric dependencies are captured derivationally, such that the two elements are linked because they have formed a constituent in the base. Different flavors of this approach vary with respect to the exact structure of the big DP. Some analyses take clitics to head the big DP with the doubled DP being projected in the specifier (Uriagereka 1995: 81); others treat clitics as adjuncts to the doubled DP (Nevins 2011); and others yet embed clitics as specifiers within a functional projection that also hosts the doubled DP (Arregi and Nevins 2012: 53ff.). These differences aside, these approaches are united in uniformly postulating that the clitic strands the DP in the course of the derivation by moving to a verbal projection, as schematized in (19), which is based on the structure of Uriagereka (1995: 81):

-

(19)

.

In big-DP approaches, then, the clitic is an independent syntactic element, projected within the big DP from the start of the derivation.

This is not so in a different class of movement-based approaches, where clitics are treated as additional realizations of the D head introducing the doubled DP. We refer to these analyses as derivational, in the sense that they take clitics to lack independent status underlyingly, and to arise over the course of the syntactic derivation. At least two implementations of the derivational approach have been put forward.

In one type of analysis, clitic doubling is derived by means of A-movement and rebracketing (Harizanov 2014; Kramer 2014): the doubled DP undergoes object shift to a peripheral position within the vP; the D head subsequently amalgamates downward with the verbal head whose specifier hosts the doubled DP, via rebracketing or m-merger (Matushansky 2006). On this type of analysis, illustrated in (20) below, it is crucial that only the lower copy of the A-moved DP and the rebracketed D head are realized.Footnote 7

-

(20)

.

A second implementation of the derivational approach takes the clitic to arise by means of long head movement (e.g., Řezáč 2008; Preminger 2009, 2011, 2019; Roberts 2010). On this approach, an Agree dependency between v and the object DP triggers movement of just the head of the DP to the probe v; the clitic is then the realization of the moved D head (Preminger 2019: 31ff.). Under this analysis, doubling arises because both the moved D and the doubled DP are realized at PF (Preminger 2019: 20), see (21):

-

(21)

.

Despite important differences between them, the theories outlined thus far share movement as a crucial aspect of the generation/placement of clitics. In big-DP approaches, the independent D head strands the doubled DP by evacuating the big DP, while in derivational approaches the clitic spells out a D head that has become amalgamated with v, either due to A-movement plus rebracketing or due to head movement.

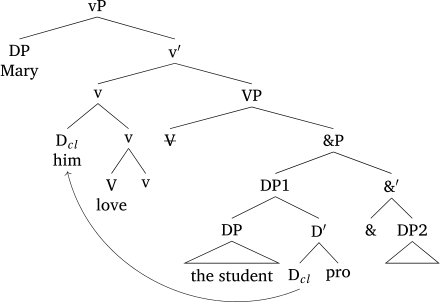

The last family of approaches treats clitics as agreement markers, viz., as a type of object agreement. The idea goes back to at least Suñer (1988), who proposes that clitics are base-generated agreement markers on the verb that form a chain with the doubled DP (which occupies an argument position). Given current assumptions about the syntax-morphology interface, such an approach would arguably be recast by having the clitic be the spell-out of ϕ features copied from the doubled DP onto a probe on a functional head via Agree. Such an approach is sketched in (22) below, where the functional head equipped with an Agree probe is labeled as F for convenience. Crucially, this approach involves only feature copying (or sharing), but no movement.

-

(22)

.

The presentation above was slightly idealized in that many approaches are actually hybrid, incorporating components of more than one theory. Quite a few in fact include (A-)movement in addition to the arguably main ingredient. For instance, the big-DP-approaches by Uriagereka (1995) and Nevins (2011) include an object-shift-like phrasal movement step before the clitic attaches to the verb (via head-movement or morphological merger). A-movement components can also be found in agreement approaches. In Sportiche (1996), clitics are treated as independent functional heads in the extended projection of the verb (in fact situated above AgrSP). The doubled DP undergoes covert movement to the specifier of the clitic head to satisfy a clitic criterion. The covert movement step is related to object shift/scrambling (where movement is overt but the functional head is silent) in that both operations are related to specificity. Depending on the clitic (Sportiche only discusses French clitics, though), the covert movement step may instantiate A- or A′-movement. More recently, Angelopoulos (2019: 21) proposes that there is a scrambling-like A-movement step of the doubled DP to a specifier of a functional head X above vP followed by Agree with a clitic head, which is situated below T (the A-movement step being a precondition for the DP to become accessible to Agree).Footnote 8

3.2 An argument in favor of a pure Agree approach

In light of the immediately preceding discussion, the relevance of our FC CLD data to theories of clitic doubling more generally becomes clear: under most of the approaches just outlined, FC CLD will lead to a violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint (CSC; Ross 1967), which bans extraction of individual conjuncts and asymmetric extraction from individual conjuncts.Footnote 9 We will first illustrate the consequences for the different approaches to CLD, then show that the CSC holds in the relevant environments in Greek, and finally address alternative structures intended to avoid the CSC-violation and alternative conceptions of the CSC.

3.2.1 The CSC and different approaches to clitic doubling

Starting with the big-DP analysis, where the clitic would be associated only with the first conjunct, movement of the clitic to the verb would involve subextraction from one conjunct and thus a CSC violation.Footnote 10

-

(23)

.

Similarly, an account based on A-movement and rebracketing would involve asymmetric A-movement of the entire first conjunct to, say, Spec,vP, again violating the CSC (24).Footnote 11

Finally, the head movement approach would postulate asymmetric head movement of the D head of the first conjunct to the verb, an instance of subextraction also in violation of the CSC, see (25):

-

(24)

.

-

(25)

.

Importantly, an approach purely based on Agree (26) does not suffer from the same problem: since this approach only involves feature-copying but not movement, it is not subject to the CSC.Footnote 12 By virtue of being the only approach compatible with the CSC (under both traditional and revised formulations of this constraint; see below), FC CLD favors an approach to CLD in Greek that rests solely on Agree.Footnote 13

-

(26)

.

Our argument parallels that by Legate (2014) and Kalin and Weisser (2019) against movement approaches to differential subject and object marking, respectively. They show that it is possible to coordinate both marked and unmarked subjects/objects. If DSM and DOM involved A-movement, such coordination would lead to a violation of the CSC.Footnote 14

3.2.2 The CSC holds in Greek

A possible objection to our claim would call into question the status of the CSC as a locality constraint. On the one hand, there does exist evidence that the CSC has semantic components, viz., requires some sort of semantic symmetry; see e.g., Fox (2000). On the other hand, there is also a class of (putative) exceptions; see Postal (1998: Chap. 3), Lin (2002), and, more recently, Bošković (2019, 2020).

In what follows, we will show that the CSC independently holds for A-movement in Greek (for reasons internal to Greek outlined below, the same cannot be done for head movement without certain confounds). In addition, we will show that there can be FC CLD in environments where asymmetric extraction would be banned even under approaches like Bošković (2019, 2020), which in principle allow for exceptions to the CSC.

We start by showing that asymmetric A-movement of an entire conjunct, as required under A-movement-based approaches to CLD, is impossible in MG. (27a) shows that a coordinated subject is fine in postverbal position. However, fronting the first conjunct to Spec,TP is impossible (27b), irrespective of the agreement on the verb. Note that the use of a collective verb ensures (for the relevant speakers, see fn. 6) that a stripping/gapping parse is unavailable in (27). Furthermore, we use a passive example; the subject is thus an underlying object and asymmetric extraction would not be independently ruled out by some other locality constraint such as a ban on extraction from external arguments. Similar examples can be constructed with other collective verbs, e.g. sigendrono ‘bring together.’Footnote 15

-

(27)

Since postverbal subjects consisting of a DP-coordination are well-formed (27a), the ungrammaticality of (27b) cannot easily be related to independent factors such as case or agreement. Rather, it is plausibly due to a violation of the CSC.Footnote 16

Importantly, clitic doubling can also occur in environments which would require subextraction from a conjunct under an A-movement approach (and also under big-DP and head movement-based accounts). The following example illustrates CLD of the ECM subject of the first conjunct (note that here, doubling the second conjunct or combining the features of both ECM subjects in resolved doubling is not possible):Footnote 17

-

(28)

Note that the negatively quantified subject rules out conjunction reduction (under the relevant reading where it is the case that no single X caused both events).

Asymmetric subextraction from a conjunct involving A-movement as would be needed in (28) can be shown to be unavailable in Greek. The following example illustrates asymmetric raising to subject:

-

(29)

Note that since Greek has backward raising (whereby the subject occurs in the complement clause rather than in the subject position of the raising verb, see Alexiadou et al. 2012), one cannot easily rule such structures out for independent reasons: the subject of the second conjunct is in the embedded clause, just like a subject in backward raising.

In this context, it is useful to discuss the CSC theory of Lin (2002: 72), which allows asymmetric A-movement from coordination under specific circumstances, namely as long as the moved DP undergoes total reconstruction (or binds a variable in the second conjunct):

-

(30)

. [Many drummers]1 can’t [__1 leave on Friday] and [many guitarists arrive on Sunday] (¬ > many)

One could therefore imagine that an example like (29) becomes grammatical if the asymmetrically extracted subject reconstructs. Unfortunately, raised subjects do not seem to be able to reconstruct for scope (i.e., take narrow scope with regard to the matrix verb/matrix negation) in Greek, see Alexiadou et al. (2012: 98f., Ex. 41a, 43a). Thus, the following example involving asymmetric raising is ungrammatical, but since narrow scope of the moved subject is independently unavailable, this is unsurprising given the theory developed in Lin (2002).

-

(31)

One might object at this point that the examples used to illustrate that Greek obeys the CSC are based o n overt A-movement; consequently, they do not necessarily rule out asymmetric covert A-movement in the derivation of clitic doubling. Indeed, it is, in principle, conceivable that A-movement in some of the movement approaches introduced above is actually covert (given that the doubled DP seems to occupy its base position on the surface). However, there is no reason to believe that covert movement is not subject to the CSC, see e.g., Bošković and Franks (2000). While they do not discuss covert A-movement specifically, given the generalization in Lin (2002), there is no reason to expect covert A-movement to be exempt from the CSC.Footnote 18

While one can demonstrate that the CSC holds for A-movement independently in the language, this is, unfortunately, not possible for head movement. This has to do with the fact that all attested instances of head-movement can be argued to be crucially implicated in deriving affixation: for instance, it could be the case that the verb moves to T to pick up tense and agreement inflection, the participle moves to Asp for participial morphology, and the verb moves to C to pick up imperative morphology. Consequently, any example where the verb in the second conjunct fails to move to the relevant head can be argued to be ruled out for independent reasons: the verb would fail to receive the necessary morphology. As such, it does not seem possible to construct an example not showing this confound. The confound of course arises only on a certain view of how affixation is effected; but this is certainly a possible view, and we lack the space to examine its correctness for Greek.

Thus, demonstrating the validity of the CSC for head-movement requires an instance of verb movement that is unrelated to affixation like English T-to-C-movement or verb second movement in Germanic. Given that the CSC has been shown to hold in such environments, see (32), we see no reason to exempt the head movement required by the relevant movement accounts of CLD from the CSC.

-

(32)

. *Should Mary buy a house and Sue could sell her car?

3.2.3 Alternative big-DP structures and different conceptions of the CSC

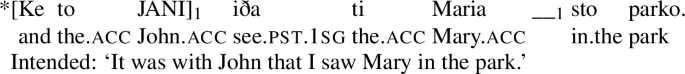

Before concluding this section, we show that our argument against movement-based approaches to CLD in Greek goes through even if we attempt to rescue these approaches by assuming a) alternative big-DP structures, or b) a more refined CSC.

Firstly, as suggested to us by Karlos Arregi (p.c.), the big-DP analysis could avoid a CSC violation if D were to be generated outside of &P as in (33) and undergo Agree with either the 1st CJ, yielding FC CLD, or &P, yielding resolved doubling:

-

(33)

.

Under this structure, movement of the clitic D would not be asymmetric, circumventing the CSC violation. In principle, this structure is indeed a viable alternative, putting to the side the question of whether it would be incompatible with the assumptions of certain individual versions of the big-DP analysis.Footnote 19 Importantly, though, this reanalysis will only work for instances of DP coordination but not for examples like (28), where what is coordinated are larger structures, e.g., vPs or TPs (the D head would have to take a coordination of vPs/TPs as its complement, which would not be in the spirit of the big-DP hypothesis).

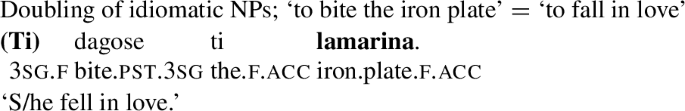

Second, recent work by Bošković (2019, 2020) has argued that the CSC does hold for successive-cyclic movement out of &P, but that it is violable if extraction involves an element that is either base-generated at the edge of the first conjunct or independently capable of moving there, with this asymmetry argued to be related to labeling. The following example from Galician is supposed to instantiate one such case of CSC avoidance. Here, the definite determiner associated with the first conjunct can asymmetrically cliticize onto the verb; since it is the head of the DP, it is located at the edge and can move without violating the CSC.

-

(34)

Given the big-DP hypothesis, FC CLD could now be predicted to be possible: movement of the clitic would take place from the edge of the first conjunct as long as the clitic is either the head of DP (35), or its specifier (36):

-

(35)

.

-

(36)

.

Given this theory of the CSC, FC CLD of coordinated DPs would no longer be ruled out under a big-DP analysis or a head-movement analysis (the derivation in the latter case would be essentially the same as in the Galician example above). For the A-movement approach, the result would be mixed. It would still fail for asymmetric extraction of the first conjunct of objects consisting of coordinated DPs, like most of the examples in this paper. However, A-movement might become a possibility for examples involving subextraction like (28) where the first ECM subject could be argued to be located on the edge of the first vP/TP conjunct.

However, even this attempt to rule in CSC violations in a restricted fashion is not sufficient to accommodate FC CLD under movement-based approaches. Once we consider different configurations, FC CLD turns out to remain incompatible with such approaches. To see why, consider the following example, which like (28) involves coordinated ECM clauses with asymmetric CLD of the first ECM subject (as in (28), doubling the second conjunct or combining the features of both ECM subjects in resolved doubling is not possible).

-

(37)

Note that the negative quantifier rules out a conjunction reduction parse (under the relevant reading where no one has scope over both events). This example crucially differs from (28) in that the adverbs at the beginning of each conjunct ensure that the ECM subjects are not at the edge of the conjunct. Consequently, under a big-DP, head-movement or A-movement approach, CLD would require movement from a position that is not at the edge of the conjunct, violating even the refined version of the CSC developed in Bošković (2019, 2020). We therefore conclude that our argument against movement-based approaches to CLD still stands.Footnote 20,Footnote 21

Importantly, for our argument against movement, it is in principle immaterial exactly how Agree-based FC CLD arises, viz., whether it results from syntactic Agree with just the first conjunct (which is equidistant with &P; see e.g., van Koppen 2005); rule ordering, where only the features of the first conjunct are projected to &P and then targeted by an Agree-probe (Murphy and Puškar 2018); labeling, where the absence of labeling of the coordination leaves the first conjunct as the only possible goal (Larson 2013); or copying from the linearly closest conjunct at PF (e.g., Marušič et al. 2015). However, given the interaction of CLD with intervention effects discussed below where clitic doubling of an indirect object deactivates it for further ϕ-Agree, only a syntactic Agree-approach is viable (while a post-syntactic account cannot deal with this type of interaction). A similar argument against a post-syntactic approach is presented in Paparounas and Salzmann (2023), where we show that FC CLD interacts with the Person Case Constraint; there, we argue that the patterns actually slightly favor an approach in terms of rule ordering.Footnote 22

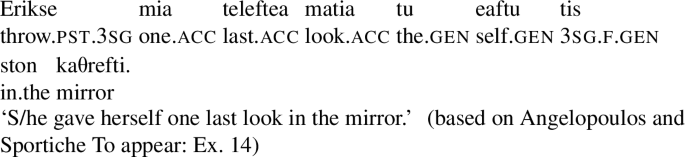

3.3 Further arguments against movement in CLD: Binding

Certain movement-based approaches to CLD make clear predictions with respect to binding: in those theories where CLD is accompanied by (overt or covert) A-movement of a DP or head-movement of the double’s D head, CLD should be able to affect binding, either by creating new binding possibilities or destroying existing ones, as the case may be. In this section, we show that this prediction is not borne out for Greek. Instead, the binding data presented here very much suggest that the doubled DP occupies its base position in this language—as such, they furnish additional evidence against an approach tying Greek CLD to A-movement or object shift/scrambling. We first establish a baseline by showing that overt A-movement, viz., raising of the subject, can affect Binding Conditions A and C in both English and Greek. In a second step, we discuss the binding profile of (local A-)scrambling in other languages. Then, we show that clitic doubling has no effect in the domain of Condition C and Condition A. Thus, its binding profile is different both from that of A-movement constructions like raising and from local A-scrambling.

We would like to point out that, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to systematically discuss the effect of clitic doubling on Binding Conditions A/C. In the literature on the topic, the evidence for (A-)movement has been based almost exclusively on an arguably more poorly understood binding-related phenomenon, namely, the alleviation of Weak Crossover Effects. That clitic doubling does not interact with binding for Condition A/C will lead us to reassess the WCO-based evidence offered ostensibly in favor of movement, in Sect. 4.2 below. As we will see, an alternative to WCO alleviation by means of A-movement, namely, one that capitalizes on the role of information structure, is readily available. We thus eventually arrive at a very different empirical picture to that given by previous literature, at least for the case of Modern Greek: clitic doubling does not affect binding.

3.3.1 The binding pattern in overt A-movement

Given that CLD has been claimed to involve A-movement, we first spell out what kind of effects on binding one expects on the basis of what is known about the binding profile of A-movement.

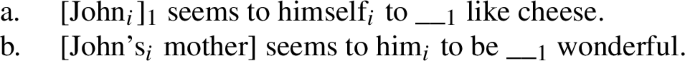

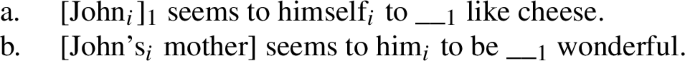

As is well known, A-movement can be interpreted in its landing site. As the following two English examples show, this can lead to new binding possibilities in the case of Condition A and alleviation of Condition C effects, see Lebeaux (2009: 32):

-

(38)

In both cases, a grammatical result only obtains if the moved XP is interpreted in its landing site. A-movement can, of course, also undergo reconstruction as e.g., in (39), where the anaphor can only be bound if the moved phrase is interpreted in the embedded clause; see Lebeaux (2009: 35):

-

(39)

. [Each otheri’s parents]1 seem to the boysi to be __1 quite wonderful.

Raising of the subject in Modern Greek displays the same properties. In both cross-clausal raising (40) and local raising to Spec,TP (41), the moved XP can be interpreted in its landing site. It thus leads to new binding possibilities for Condition A in the (a) examples and alleviates Condition C effects in the (b) examples (see Anagnostopoulou 2003: 171–176 for evidence that fenete is a proper raising verb).

-

(40)

-

(41)

As in English, in Greek A-movement can also reconstruct. In (42), a grammatical result only obtains if the raised subject is interpreted below the experiencer, see Angelopoulos and Sportiche (To appear: Ex. 23c) (for more Condition A reconstruction data, see Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 2002: 21):

-

(42)

Thus, if CD involves A-movement, we expect a pattern where the clitic-doubled XP can be interpreted either in its purported landing site (around Spec,vP) or in its base-position (if it reconstructs).

Slightly different predictions arise if, as already mentioned in fn. 8, the A-movement operation postulated for Greek clitic doubling is assimilated to instances of overt A-movement such as object shift and (local A-)scrambling in other languages. This link has been entertained largely due to certain parallels with respect to the DPs eligible for doubling in doubling languages, and those eligible for object shift/scrambling in scrambling languages; see e.g., Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (1997) (but recall from fn. 8 that there are also significant mismatches).

Before discussing the Greek binding data, it is therefore instructive to look at the binding-theoretic effects of object shift/scrambling. In what follows, we illustrate the relevant data on the basis of German scrambling, as it can reorder arguments. As shown in Haider (2010: 148f.), scrambling affects Condition A and Condition C (as well as variable binding/Weak Crossover, which we discuss in Sect. 4.2 below).

The first pair shows that scrambling can feed Condition A/C (leading to grammaticality in the former and ungrammaticality in the latter; note that the assumed base order is  ):

):

-

(43)

The second pair shows that scrambling can destroy binding relations, which in the case of Condition A leads to ungrammaticality and with Condition C to an alleviation; the assumed base order is  and

and  , respectively):

, respectively):

-

(44)

There is a clear generalization evident in the data just discussed: scrambled phrases are interpreted in their surface position for the purposes of binding. Crucially, unlike other types of A-movement (e.g., raising to subject discussed above), scrambled phrases do not systematically reconstruct for binding. The same binding profile is reported for local scrambling in Hindi by Mahajan (1990: 34–36): scrambled XPs are interpreted in their surface position and do not reconstruct.

Thus, the alleged parallel with scrambling furnishes an expectation slightly different to the one yielded by the parallel with overt A-movement: while the raising data lead us to expect that, on an A-movement account of clitic doubling, the doubled DP should have the option of reconstructing, the scrambling data make us expect a binding profile for clitic doubling that differs from other types of A-movement in not allowing reconstruction at all. In what follows, we show that, on either parallel, the predictions of A-movement-based approaches are not borne out: doubled DPs are always interpreted in their base positions.

In the following sections, we will look at Condition C and Condition A configurations in Modern Greek. There will be two DPs within vP and only the structurally lower one will be clitic-doubled. Under A-movement or head-movement, we expect (part of) the doubled DP to actually occupy a structurally higher position, above the first DP, which should affect binding:

-

(45)

cli-V [DP2 ...i]1 ... [DP1 ... ] ... [DP2 ...i]1

As we will see, there is no evidence for A-movement: Greek clitic doubling has the binding-theoretic profile neither of raising nor of scrambling. Rather, the doubled XPs behave as if they occupy their argument position.

3.3.2 Condition C

We first discuss the effect of CLD on Condition C, investigating two relevant configurations. The first configuration can be schematically depicted as in (46):

-

(46)

. cli V [\(_{\text{DP1}}\) R-Expj] [\(_{\text{DP2}}\) X of R-Expj]i

This configuration can be used to test the predictions of the A-movement approach: if DP2 underwent A-movement across DP1 (e.g., to Spec,vP), it should alleviate Condition C.Footnote 23 However, this prediction is not borne out; irrespective of whether the clitic is present or not, examples of this type are strongly ungrammatical. In (47a), this is shown for DP1 = IO and DP2 = DO; in (47b), it is shown for DP1 = SU and DP2 = IO. Note that the base order in Greek is SU > IO > DO; see e.g., Anagnostopoulou (2003: 137–143):

-

(47)

These data thus argue against A-movement (while the head-movement approach correctly predicts no effect on binding given that the R-expression within the clitic-doubled phrase is not affected by head-movement).

The second relevant configuration is illustrated in (48):

-

(48)

. cli V [\(_{\text{DP1}}\) X of R-Expj] [\(_{\text{DP2}}\) R-Expj]i

With this configuration, we can test the predictions of both the A-movement and the head-movement approach: if DP2 underwent A-movement across DP1 (to Spec,vP), it should cause a Condition C effect. We expect the same under a head-movement approach if the referential index is on the D-head of DP2 and this D-head moves across DP1. However, that is again not what we find: whether the clitic is present or not, such examples are well-formed. In (49a), this is shown for DP1 = IO and DP2 = DO, while in (49b), it is shown for DP1 = subject and DP2 = DO:Footnote 24,Footnote 25

-

(49)

Of course, if A-movement can undergo total reconstruction, the data in (49) do not, in principle, argue against A-movement.Footnote 26 But given the binding profile of local scrambling in other languages, viz., the absence of reconstruction for binding, the lack of interaction between clitic doubling and Condition C would still be rather unexpected if clitic doubling is essentially an abstract version of scrambling. Together with the data in (47) and thus the absence of any positive evidence for A-movement, a different and much simpler generalization emerges: clitic doubled DPs occupy their base position and do not undergo A-movement or head-movement. A-movement-based theories could, of course, postulate in the face of this data that, unlike virtually all well-understood instances of A-movement, the A-movement step involved in doubling always reconstructs; but the burden of proof would rest with this assertion, not with what seems to be the null hypothesis given the data just examined, namely, that clitic doubling is found to pattern differently from A-movement precisely because it does not involve A-movement.

Note that the binding data do not argue against the big-DP hypothesis as long as the doubled DP does not move and the D-head is not semantically interpreted (viz., is not subject to Condition B).

As a final point, the data in the first configuration provide further evidence against the dislocation theory of clitic doubling: the doubled DPs clearly behave like DPs in their argument position rather than like DPs base-generated outside the c-command domain of the first DP (recall the discussion in Sect. 2.1); under dislocation, the DO/IO-clitic would be the argument and no Condition C effect would be expected given that the doubled (and thus dislocated) DO/IO containing ‘John’ would be outside the c-command domain of ‘John.’Footnote 27

3.3.3 Condition A

The previous section established that in Greek, CLD fails to affect binding for the purposes of Condition C. This section does the same for Condition A, thereby furthering the generality of our binding-based argument against movement-based approaches to Greek CLD. In what follows, we investigate the effect of CLD on Condition A in two environments. The first one involves an anaphor IO and a clitic doubled DO, schematically represented in (50):

-

(50)

. cli V SU [\(_{\text{DP1-IO}}\) anaphorj] [\(_{\text{DP2-DO}}\) R-Expj]i

The second configuration involves a subject anaphor and a clitic doubled DO, as represented in (51):

-

(51)

. cli V [\(_{\text{DP1-SU}}\) anaphorj] [\(_{\text{DP2-DO}}\) R-Expj]i

We begin our investigation with reflexive binding, before moving on to the understudied Greek reciprocal pronoun and, finally, the periphrastic reciprocal construction.

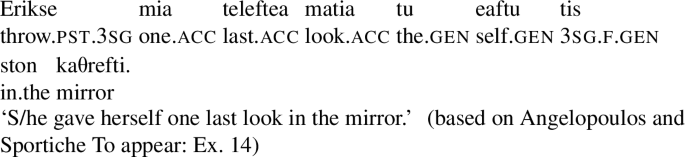

Consider firstly the Greek reflexive anaphor. (52) is a baseline example showing that, in a ditransitive, a DO reflexive can be bound by an IO antecedent, as expected given the c-command relations outlined above. Note that this example also shows that the Greek reflexive is not subject-oriented.Footnote 28

-

(52)

Given (52), we expect that an IO reflexive co-indexed with the DO will fail to pass Condition A. This is indeed what we find (see also Michelioudakis 2011: 81):

-

(53)

Consider now once again the predictions made by A-movement approaches to CLD: we should be able to repair (53) by doubling the DO, thereby raising it to a position c-commanding the reflexive. This prediction is not borne out:

-

(54)

Once again, to ensure that (54) really does speak against A-movement-based accounts, we must eliminate possible confounds.

One such confound is found in the claim that the Greek reflexive cannot be marked with genitive (Anagnostopoulou and Everaert 1999: 111).Footnote 29 This does not seem to be the case for the grammars of the native speaker author and our consultants, who readily accept examples like (55), and spotaneously produced similar ones. Additionally, Angelopoulos and Sportiche (To appear: Sect. 4.1) provide further evidence that genitive IO reflexives are grammatical, explicitly controlling for the reified non-reflexive usage of the anaphor by predicating concrete properties of the reflexive, see (56).

-

(55)

-

(56)

The descriptive grammar of Holton et al. (2012) also lists genitive IO reflexives as grammatical, noting however that they appear “more often in a prepositional phrase”; genitive goals being the marked alternative to PP goals in Greek in general, this is not surprising.

-

(57)

Thus, there is, in our view, no reason to question the validity of our argument on the basis of the possible markedness of genitive reflexives.

To further buttress our claim, we note that one can show the same lack of effect of clitic doubling on binding by using transitive verbs with the anaphor as the nominative subject and the antecedent as a clitic doubled direct object, in the second configuration introduced above (see also Angelopoulos and Sportiche To appear: Ex. 32b):

-

(58)

If there were A-movement of the DO across the nominative, we would expect such examples to be well-formed, contrary to fact.Footnote 30 Since nominative anaphors are unquestionably grammatical in Greek, we conclude that there are no empirical reasons to question our argument based on Condition A.

Examples like (58) thus show that CLD does not yield new binding possibilities for a subject reflexive: This example argues not only against A-movement approaches; rather, under the assumption that the referential index is on D, the head movement approach also incorrectly predicts clitic doubling to feed binding in this configuration.

(59) shows the other side of the same coin: clitic doubling the anaphor does not cause it to raise above its antecedent and violate Condition A.Footnote 31

-

(59)

Of course, if the kind of A-movement involved in clitic doubling can totally reconstruct, this fact is not problematic. We would like to stress again, though, that this would be different from the binding profile of local scrambling in languages like German, which usually does not reconstruct for binding. Together with the lack of evidence that doubling leads to new binding possibilities, we arrive at the same generalization as for Condition C: the doubled DP behaves as if it occupies its base position. This is unexpected under an A-movement-based account of CLD.

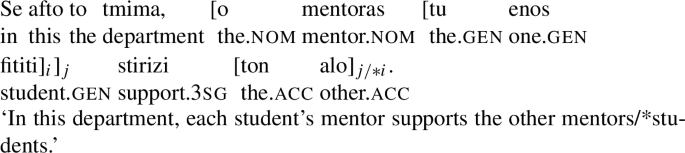

Additional evidence against A-movement in CLD comes from the Greek reciprocal (Paparounas and Salzmann To appear), which consists of two elements, the distributor the one and the reciprocator the other (cf. English one another and apparently similar constructions in Italian, Belletti 1982, and Icelandic, Sigurðsson et al. 2022). Both parts are always morphologically singular. The case of the one matches the case of the antecedent DP ( in (60)), while the other is marked for the case of the structural position of the reciprocal itself (

in (60)), while the other is marked for the case of the structural position of the reciprocal itself ( in (60)); despite appearances in what follows, the two elements do not form a constituent (see (69) below):

in (60)); despite appearances in what follows, the two elements do not form a constituent (see (69) below):

-

(60)

Both parts agree in gender with the plural antecedent:

-

(61)

The one must always be structurally higher than/precede the other (62a), and the whole construction must be c-commanded by the plural antecedent (62b), (63); cf. Lapata (1998).

-

(62)

-

(63)

Additionally, the usual restrictions on binding domains hold: the reciprocal requires a local antecedent (the domain roughly corresponding to the smallest XP containing the anaphor and a distinct subject).

-

(64)

In a ditransitive, the reciprocal can freely occur as IO; there is no restriction against marking a reciprocal genitive (65):Footnote 32

-

(65)

The relevant example to construct would thus involve a reciprocal IO co-indexed with the DO. Since the IO c-commands the DO in Greek (Anagnostopoulou 2003: 137–143), we expect the relevant example to be ungrammatical; this is indeed what we find:

-

(66)

Note that (66) is ungrammatical not because of any restrictions on the position of the reciprocal itself (cf. (65)), but for binding-theoretic reasons, namely, Condition A.

Consider now the prediction made by DP-movement-based approaches to CLD. If CLD in Greek involved A-movement of the doubled DP to a peripheral position in the vP, it should be possible, all things being equal, to rescue examples like (66) by CLD. This is so because, under a movement-based approach, clitic doubling the DO should raise it to a position that c-commands the reciprocal IO. Crucially, this prediction is not borne out: the doubled version of (66) is (67), and the two examples are equally ungrammatical.

-

(67)

The ungrammaticality of (67) cannot be attributed to a hidden third factor. For example, it is not the case that the reciprocal is subject-oriented (see fn. 33); it is also not the case that the reciprocal cannot be marked genitive (65).Footnote 33

The failure to create new binding possibilities can also be shown in the second configuration introduced at the beginning with the reciprocal as the subject and the antecedent as a direct object. Again, the clitic doubled version in (68b) is just as ungrammatical as the undoubled baseline in (68a), pointing towards the absence of A-movement. Note that the ungrammaticality of (68a) cannot be attributed to some restriction on case marking, as the one can freely be nominative as in (69).

-

(68)

-

(69)

The data thus far show that CLD of a DO cannot yield new binding possibilities for a SU/IO reciprocal, arguing against both the A-movement approach and the head-movement approach (under the assumption that the referential index of the DO is on D). Unfortunately, it cannot be shown that CLD fails to destroy binding configurations with reciprocals because the reciprocal cannot be clitic-doubled.

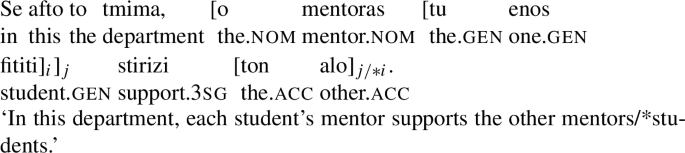

Alongside the split-case reciprocal discussed in the previous section, Greek has a distinct reciprocal construction whereby the distributor ‘the one’ appears in an A-position; call this construction the A-reciprocal.

-

(70)

The A-reciprocal resembles familiar binding constructions in obeying a c-command requirement: ‘the other’ must be c-commanded by (the constituent containing) ‘the one’ for a reciprocal interpretation to emerge.

-

(71)

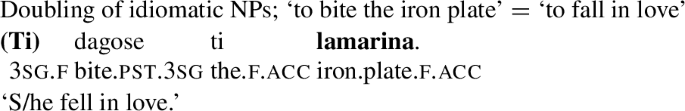

However, this construction is different from the bona fide reciprocal pronoun in that, as can be seen in (70) and (71), there is no plurality requirement on its licensing. Moreover, the A-reciprocal is not subject to the locality restrictions on syntactic A-binding (in that o alos can be an embedded object):

-

(72)

It thus seems likely that the A-reciprocal is more akin to variable binding than to syntactic anaphor binding (the properties of reciprocal constructions of this kind, including the English translation of (72), itself grammatical, are understudied; see Jackendoff 1990: 435 and references cited there for data from English). However, since the crucial ingredients involved are binding under c-command from an A-position, this construction still allows us to test the predictions of A-movement-based theories of CLD.

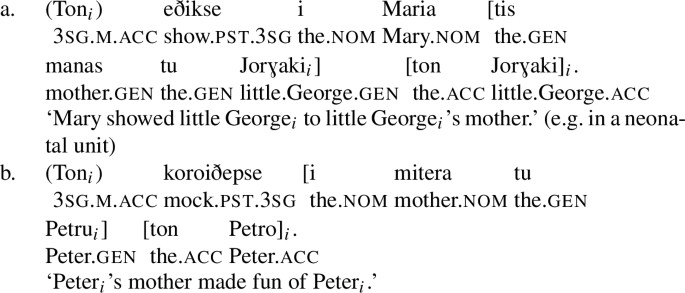

In Anagnostopoulou (2003: 140), examples of the following form using the A-reciprocal are used to argue that Greek IOs asymmetrically c-command DOs:

-

(73)

Importantly for our purposes, the CLD counterpart of the grammatical (73a) is itself grammatical:

-

(74)

The grammaticality of (74) is unexpected if there is A-movement of the bound element across its binder, as this instance of movement would destroy the correct c-command relationships that the pre-movement structure supplies. Of course, as discussed above, this objection only holds if A-movement does not obligatorily reconstruct; again, however, if A-movement did obligatorily reconstruct, the alleged parallel with scrambling would not obtain in the first place. Unfortunately, it cannot be shown that CLD fails to create new binding possibilities with the A-reciprocal because doubling of the distributor o enas is independently ruled out.

In summary, based on data from reflexive binding, we have argued that CLD neither destroys binding possibilities nor salvages ungrammatical binding configurations. This conclusion was supported with data from reciprocal constructions: the reciprocal pronoun shows that CLD cannot create new binding possibilities, and the A-reciprocal shows that it cannot destroy existing ones. Taken together with the evidence from Condition C discussed in the previous section, the considerations in this section suggest that the empirical picture from binding is precisely the opposite to what A movement-based analyses (and, to some extent also head-movement-based analyses) of CLD would predict: rather than having the binding profile of raising constructions or local scrambling, the doubled DPs’ binding behavior suggests that they occupy their argument position. This is, of course, expected under an account that solely relies on Agree.

Note that, while Agree can copy phi-features at a distance, it does not affect binding, as shown by the contrast in (75) from den Dikken (1995: 348).

-

(75)

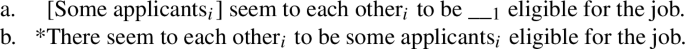

4 Challenges for an Agree-based account

In this section, we address possible challenges for an approach to CLD purely based on Agree. These include (i) the distribution of clitic doubling, which is restricted to DPs with certain semantic/pragmatic properties and (ii) two observations from the literature that seem to support a movement analysis of CLD. The first observation is that CLD can alleviate Weak Crossover and the second that CLD can void intervention effects. We show below that there are straightforward ways of restricting clitic doubling to certain DPs and the observations ostensibly supporting movement can actually be reanalyzed, and, upon closer inspection, in fact do not support a movement approach.

4.1 Distribution of clitic doubling

As in other languages, CLD in Modern Greek is restricted in its distribution, viz., not every DP can be clitic-doubled. As an approximation, clitic doubling is most likely with DPs high on the referentiality/topicality scale, viz., DPs that are topical, given/D-linked, definite, specific etc. (see Anagnostopoulou 2017a). However, it is fair to say that the precise restrictions are still poorly understood. While doubling usually targets definite DPs, there are clear cases where what is doubled is definitely not high on the referentiality/topicality scale, as shown for instance in Angelopoulos (2019). These include quantified DPs, non-specific indefinites, and even focused experiencers.Footnote 34 In addition, clitic doubling is hardly ever obligatory even if a DP is eligible for doubling.Footnote 35 We will not attempt to contribute to this debate here but instead focus on the consequences these obsevrations have for a pure Agree-approach. Clearly, without further restrictions, an Agree approach without movement predicts clitic doubling to be possible with any DP that carries phi-features.

At first sight, things seem different with approaches involving A-movement. Under such an approach (see e.g. Harizanov 2014; Kramer 2014; Angelopoulos 2019) one can assume that the semantic/pragmatic features of the DP govern object shift. If object shift applies, the DP gets close enough to undergo rebracketing (Harizanov 2014; Kramer 2014) or Agree (Angelopoulos 2019) and a clitic results. Without such movement, rebracketing/Agree is impossible and no clitic obtains (presupposing strict locality conditions on the relevant operations). However, since the parallel between object shift/scrambling and CLD is far from perfect (see fn. 8 and much discussion above) and since doubling can also involve non-specific indefinites, as mentioned above, it is unclear how to regulate the distribution of CLD by means of movement: movement would also have to apply to DPs that would normally not undergo object shift (viz., that have the “wrong” semantic features). Conversely, given the optionality of clitic doubling, even DPs with the required semantic properties would fail to undergo object shift. Because of these dissociations, the distribution of clitic doubling also constitutes a challenge for A-movement approaches.Footnote 36

A syntactic implementation of the distribution of CLD that is compatible with a pure Agree-approach is the licensing approach to Differential Object Marking by Kalin (2018, 2019). The underlying idea is that in languages with DOM, only DPs with certain features require licensing. DPs are licensed by means of Agree. This can be understood as a generalization of the Person Licensing Condition for local person arguments first proposed in Béjar and Řezáč (2003). The technical implementation in Kalin (2019) involves associating the features that require licensing, e.g, [specific], with a derivational time bomb [ ], which unless defused (viz., agreed with) causes the derivation to crash. The advantage of such an approach to DOM is that it is compatible with DOM patterns that involve agreement rather than case and crucially need not rely on movement (in the language studied by Kalin there is no evidence that DOM-marked DPs occupy syntactically higher positions than unmarked DPs). While the Agree probe on T is taken to be obligatory, an economy principle restricts the presence of a secondary licensor, viz., an Agree probe on v, such that such a licensor is only merged if necessary for convergence.

], which unless defused (viz., agreed with) causes the derivation to crash. The advantage of such an approach to DOM is that it is compatible with DOM patterns that involve agreement rather than case and crucially need not rely on movement (in the language studied by Kalin there is no evidence that DOM-marked DPs occupy syntactically higher positions than unmarked DPs). While the Agree probe on T is taken to be obligatory, an economy principle restricts the presence of a secondary licensor, viz., an Agree probe on v, such that such a licensor is only merged if necessary for convergence.

This logic can be directly extended to clitic doubling, which is thus treated as an instance of DOM. Concretely, objects with certain semantic/pragmatic properties, e.g., [def, spec etc.] will carry a derivational time-bomb. A derivation will only converge if there is a secondary licensor, viz., an Agree probe that agrees with this object DP. If a DP has no such feature, no licensing via Agree is necessary and a secondary licensor is not possible and thus no CLD arises. Note that such an approach does not provide a deeper understanding of the distribution of CLD and has nothing to say about the optionality other than that the time-bomb is optional in some cases. But if the distribution of CLD is to be captured by syntactic means without movement, this is a straightforward solution (another non-movement alternative to capture the distribution is proposed in Baker and Kramer 2018, where CLD of certain DPs is blocked because they undergo QR across the interpretable clitic and thus would lead to Weak Crossover).

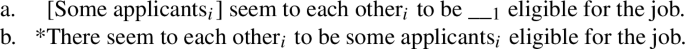

4.2 Weak crossover

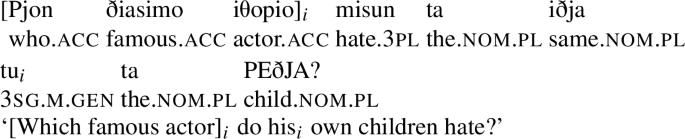

We now turn to the first observation that has been taken to directly support a movement approach to CLD, viz., the alleviation of Weak Crossover (WCO) effects. As observed in Anagnostopoulou (2003: 207f.), a configuration that violates WCO on the surface (because the constituent containing the bound pronoun c-commands the quantified DP) becomes grammatical once the quantified DP undergoes clitic doubling (our example differs from those used in Anagnostopoulou 2003 to avoid issues pertaining to optional subject reconstruction):

-

(76)

Given that A-movement is known to alleviate WCO (cf. Every studenti seems to hisi advisor to be brilliant and the Greek data in Angelopoulos and Sportiche To appear: Ex. 41, 42), the alleviation in (76) is expected if the doubled DO undergoes A-movement across the IO (e.g., to Spec,vP). The facts potentially also follow under the head-movement approach if the relevant quantificational information is part of the D-head. The structure of Greek QPs raises questions here, though, since they are headed by a definite determiner (see Angelopoulos 2019: 15 for arguments that the head-movement approach cannot account for WCO alleviation). Under an account where doubling solely arises via Agree, however, this kind of interaction is prima facie unexpected: in the absence of movement, it is unclear why CLD ostensibly repairs an illicit quantifier-variable configuration.

However, the empirical situation is considerably subtler. For one, doubling of DPs containing a bound pronoun is not ruled out (pace Anagnostopoulou 2003: 20–21; Baker and Kramer 2018: 1077):

-

(77)

This shows that doubling fails to destroy binding relationships, contrary to what we would expect if the DO moved across the IO: the bound pronoun would be removed from the c-command domain of the QP. Conversely, the facts are compatible with the head-movement approach given that the bound pronoun is not the head of the DP and thus would remain in situ.

Angelopoulos (2019: 7) also provides an example where pronominal binding by an IO is possible even though the DO is clitic-doubled. He comes to a very different conclusion, though, namely that A-movement can undergo total reconstruction (and argues against the claims in Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1997: 144–146 that such reconstruction is impossible). As discussed above with regard to Condition A and C, while A-movement can in principle reconstruct (also in variable binding, see Angelopoulos and Sportiche To appear: ex. 31b) and the data in (77) are thus in principle compatible with an A-movement approach, it should be pointed out that local scrambling in other languages does not systematically reconstruct for variable binding; see e.g., Haider (2010: 150) on German:

-

(78)

At the very least, the binding profile of CLD is again different from scrambling, casting doubts on attempts to link the two phenomena. Furthermore, since we believe that all evidence in favor of A-movement can be insightfully reanalyzed (see this section on WCO and intervention effects in Sect. 4.3), a more coherent account is possible if there is never any A-movement in CLD in the first place.

We will now proceed to propose an alternative to account for the influence of CLD on WCO that is compatible with a pure Agree approach. It seems likely that CLD repairs WCO not by virtue of movement, but because of its information-structural correlates, which have been independently shown to repair WCO effects (see Baker and Kramer 2018: 1075–1080 for a similar perspective.)

It has been known for quite some time that Weak Crossover can be alleviated under certain information structural conditions, see Safir (2017: 23ff.) for a recent overview and references. Detailed discussion can be found in Eilam (2011: 150ff), where it is noted, among other observations, that WCO effects can be alleviated if the intended binder is interpreted as given/D-linked/topical (and [part of] the constituent containing the bound pronoun as focal). A relevant English example, from Zubizarreta (1998: 11), is given in (79):

-

(79)

Importantly, given that clitic-doubled DPs are usually given/familiar (recall the previous section), the alleviation observed in (76) may actually be rather similar to that in (79) and, crucially, be due to the information structural properties of the binder. A-movement/head-movement may therefore no longer be necessary to account for the effect.

Crucially, WCO alleviation can be detected in Greek independently of clitic doubling, and solely by virtue of information-structural manipulations. For instance, by restricting the discourse set (viz., D-linking), WCO-configurations can be improved. In the following triple, the first example is quite unacceptable. (80b) involves clitic doubling and is fully acceptable. Crucially, (80c), which involves a D-linked wh-phrase, is quite acceptable without clitic doubling.

-

(80)

Focus on parts of the DP containing the bound pronoun has a similar ameliorating effect. Thus, a version of (80a) becomes quite acceptable in this context (note that the wh-phrase is not D-linked here):

-

(81)

As in English (Eilam 2011: 150–175), combining more than one of the above information-structural manipulations results in complete WCO alleviation, yielding perfect sentences; for Greek, the resulting sentences are thus on a par with clitic doubling repairs. Here we illustrate with the combination of a D-linked wh-phrase and a focus particle:

-

(82)

-

(83)

Turning to non-movement examples with quantifiers, without any information-structural manipulation, they are just as unacceptable as in English:

-

(84)

However, given the right context, such examples become grammatical, as shown by the Greek counterpart of English (79) above (the different discourse status of the QP can also be seen in the fact that it can undergo CLLD in this context):

-

(85)

The empirical generalization seems to be that WCO examples improve considerably with one information-structural manipulation (D-linking or focus), and become fully acceptable with two such manipulations or with CLD.

We thus observe that doubling and information-structural manipulations both alleviate WCO. The obvious question, then, concerns why this should be. To offer a preliminary answer, it is necessary to first be precise about the effect of clitic doubling. As mentioned above, doubling of a DP is usually possible only if that DP is discourse-given/backgrounded. The following examples and accompanying scenarios illustrate this requirement:

-

(86)

-

(87)

In other words, as is widely recognized, CLD does not come “for free”; rather, there exist information-structural conditions on its application. A plausible explanation for WCO alleviation now comes into view, one whereby the factor responsible for this effect is not CLD itself, but rather the information-structural conditions that make CLD possible. On this view, information structure is the hidden “third variable” governing the pattern we observe on the surface: the observed correlation between WCO alleviation and CLD does not point to a causal connection between the two, effected by movement, but rather to the presence of a third factor underlying both CLD and WCO alleviation independent of CLD, operative in the domain of discourse.

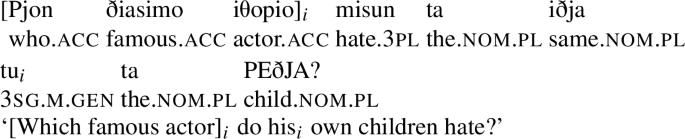

Though identifying the exact nature of this factor is beyond our scope here, we suggest that it is readily possible to understand how givenness, a prerequisite on clitic doubling, is involved here. What the information-structural manipulations discussed above have in common is that they restrict the reference set denoted by the wh-word or quantifier; for instance, overtly modifying a generic wh-word like who to yield a phrase like which famous actor specifies a narrow set of alternatives from which the question can be answered, namely, the set of famous actors. Interestingly, set restriction—by contextual means or not—contributes significantly to the amelioration of such examples. For example, (80c) above would be acceptable as a headline on the cover of a glossy magazine (Revealed: Which famous actor do his children hate?), but becomes even better if the set of alternatives is restricted more explicitly (e.g. Revealed! Tom Hanks, Alec Baldwin, Jack Nicholson: Which famous actor do his children hate?). Focus arguably performs a similar function: in (83), for example, the focus-sensitive operator even specifies that the proposition in which it is embedded is rare or surprising, signaling that the set of entities from which the question can be answered is quite small (put simply, the set of people hated by everyone, even their own children, is presumably rather restricted).

Strikingly, the givenness condition on doubling seems of the same ilk: the doubled DP must be part of the restricted set of discourse-given entities in order to undergo CLD. Illustrated in (86)–(87), this fact is also seen clearly with reference to (80b). Doubling does make this example perfect, but only if the context satisfies the givenness condition on doubling: the example is most felicitous if a set of possible referents has already been established (e.g., a context where we are trying to assess which of four prominent aristocrats is most in danger of being assassinated by their power-hungry children, thus asking Who is hated by their own children?).Footnote 37

From this perspective, it is not surprising that information-structural manipulations and CLD pattern together. We leave open at this point how this effect is to be modeled, including whether it can be integrated into a syntactic account or whether the facts discussed here speak in favor of a purely pragmatic account of WCO. See Safir (2017) for some discussion.

The question remains why doubling has a stronger ameliorating effect on WCO than focus or D-linking on their own. We speculate that givenness restricts the reference set more than such information-structural manipulations on their own. Descriptively, while, say, D-linking supplies an instruction for the answerer to look in the set of famous actors, doubling, constrained by givenness, asks the answerer to look in the set of entities already mentioned in the discourse, which is very likely a much smaller set. Combining overt set restriction with discourse-givenness will constrain the search space even further, specifying it as the set of famous actors already mentioned in the discourse; assuming that WCO is alleviated more the narrower the set of alternatives is (for reasons left to be explained), we thus expect sentences combining more than one information-structural manipulation to be perfect, and this expectation is borne out, as discussed with reference to (82)–(83).

We believe that this information-structural perspective provides an account of the facts that is not only very plausible, but also more unified. An A-movement approach to CLD is certainly compatible with the ameliorating effect of clitic doubling on WCO, but has nothing to say on why WCO is also alleviated in a range of configurations that do not involve clitic doubling. Compared to an analysis that combines a movement-based explanation of clitic doubling-induced alleviation with a wholly separate account of information-structural alleviation, an explanation that reduces both effects to a single factor, namely, the level of information structure, seems more parsimonious.Footnote 38

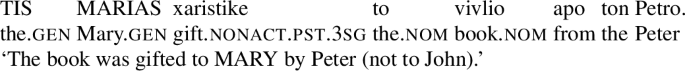

4.3 Intervention

The second observation which has been used as evidence for movement and thus potentially constitutes a challenge for an Agree-based account comes from intervention effects. As observed by Anagnostopoulou (2003: 45, 187), in the presence of an IO, agreement between T and a low passive/unaccusative subject or an embedded subject in a raising configuration is only possible if the IO is clitic-doubled (note that the restriction applies to both agreement with a low nominative and A-movement of a low nominative across the IO. For the latter, see Anagnostopoulou 2003: 20–29):

-

(88)

This interaction is, of course, reminiscent of experiencer intervention in other languages and suggests that the IO blocks Agree between T and the subject. The effect of CLD follows under a movement account if the genitive DP (or the D head of the IO) moves ‘out of the way’ before T probes (and the trace of the IO is invisible). Under a pure Agree account, it is not immediately clear how to account for this effect.

Before discussing possible solutions under Agree, it must be pointed out that, upon closer inspection, the intervention data are also potentially challenging for movement approaches. Regarding big-DP approaches, how they fare crucially depends on the structure of the big DP: if the clitic is adjoined to the DP as in Nevins (2011) or merged as a specifier of the big DP (Arregi and Nevins 2012), there will still be an intervention effect given that the IO big DP will asymmetrically c-command the nominative. The intervention problem can only be handled if the clitic is actually the head of the big DP and moves away (cf. Uriagereka 1995). In that case, the doubled DP is embedded within the big DP and does not c-command the nominative. As has repeatedly been pointed out above, A-movement approaches usually assimilate the movement step to object shift/scrambling to Spec,vP or a position immediately above it (e.g., Harizanov 2014; Angelopoulos 2019). However, to remove the IO from the c-command domain of T, the IO would actually have to move to Spec,TP and thus require a movement step that is crucially different from object shift. Thus, without significant revisions, A-movement approaches actually cannot account for the intervention effect. Under a head-movement approach, the facts follow (e.g., Anagnostopoulou 2003), but they crucially require the probe that generates the clitic and triggers head-movement to be on T as well, a potentially nontrivial complication that is not addressed in that line of work (we will turn to this issue in Sect. 5.1 below).