Abstract

Spanish comparatives have two morphemes that can introduce the standard of comparison: the complementizer que (‘that’) and the preposition de (‘of’/‘from’). This paper defends the idea that comparatives introduced by the standard morpheme de are phrasal comparatives that always express overt comparison to a degree. I show how this analysis derives the key properties of de comparatives, including the fact that they are acceptable in a much more restricted set of environments than their que counterparts. The latter are argued to involve additional covert structure, which accounts for their general flexibility. If correct, these data point to a previously unnoticed locus of cross-linguistic variation in comparative formation, whereby a standard morpheme is subject to semantic as well as syntactic well-formedness conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an overview, see Sáez and Sánchez López (2013). Works that have attributed the limited distribution of de comparatives to syntactic factors include Bolinger (1950, 1953), Solé (1982), Plann (1984), Price (1990), Gutiérrez Ordóñez (1994a,b), Sáez del Álamo (1999) and Gallego (2013), a.o. Works that have tried to explain it in terms of the denotational properties of de comparatives include Bello (1847), Prytz (1979), Rivero (1981), and Brucart (2003), a.o.

Here “degree” is used as an umbrella term that covers all types of measures; quantities, amounts, sizes, volumes…all are referred to as degrees.

The struggle to characterize the source of this variation is not new: Bello (1847: 301) already notes that although que may be admissible in some contexts similar to (5), the de variants “sound better” (sic).

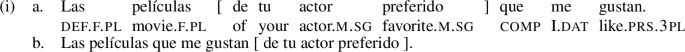

The sentence in (7) is grammatical as a partitive construction, which also makes use of the preposition de, resulting in a construction superficially identical to a comparative construction. They are not to be confused. In these cases, the interpretation of the sentence is that of a simple additive; for (7), we have that Pedro ate some more apples from that set of apples. Unless specifically noted, all the reported judgments are about comparative constructions alone.

As before, the sentence may be construed as a partitive construction interpreted as a simple additive. Judgments only address the comparative constructions.

As an anonymous reviewer points out, there could be independent reasons to rule out configurations like (21b), such as difficulties to recover a meaningful antecedent. Thus, while an underlying structure like “Yesterday my robot jumped more than 〈

my robot jumped〉 [that-much]d today” is conceivable and interpretable, its interpretation involves additional steps which may result in further complexity.The speaker variation mentioned earlier in Sect. 2.1 with respect to (5) could be related to que’s greater flexibility: it is conceivable that while in some idiolects que expresses any comparison, thus overlapping with de uses, in others the two are in complementary distribution. In comparison, the data regarding the distribution of de comparatives is much clearer, only with a few exceptions; see Sect. 7.2.

This is a difficult task. Given current degree-based analyses of comparatives, standards of comparison also constitute degree expressions even in clausal comparatives—either a maximalized degree (type d) or a set of degrees (type 〈dt〉). Moreover, one could appeal to a theory where the standard moves from its base position, resulting in a type d trace in the launching site. These concerns are difficult to address partly because the discussion quickly leads to theory-dependent reasoning. Thus, it could be that the right choice of theoretical assumptions captures the properties of de comparatives by appealing solely to a semantic requirement. While I regard this as a possibility that is worth exploring further, I will continue to assume that de comparatives are subject to a syntactic as well as a semantic restriction, as expressed in (3).

In fact, many theories derive truth-conditions for (33) along the following lines: the degree d such that the table is d-long > the degree d’ such that the table is d’-wide, where two definite degrees are said to be in a “greater than” relation to each other.

The adjective ancha in the subordinate clause overtly moves to the edge of the clause, prior to the movement of the operator that abstracts over degrees. This inversion pattern is known from Spanish focus inversion constructions (Ordóñez 1997) as well as questions (Ormazabal and Uribe-Etxebarria 1994), and comparatives (Reglero 2007).

This categorical distinction can be formally captured by exploiting the fact that the two standard morphemes belong to two distinct syntactic categories, thereby imposing different c-selectional restrictions. This can be modeled by means of uninterpretable features [uF], syntactic features which must be valued by a matching [F] feature on its sister node, and some principle (e.g. Full Interpretation) that obligatorily requires all uninterpretable features to be deleted prior to interpreting any one tree structure (e.g. Chomsky 2001). As is usually assumed, we can take the feature specification of a preposition such as de to be [P,uD], and that of a complementizer like que to be [C[-wh],uT], effectively forcing de to take DP and que to take TP complements.

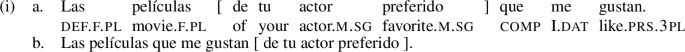

Notice that, although PPs may extrapose in certain contexts like (i), this is not allowed when they are embedded within a Degree Phrase, as in additives (ii).

As mentioned earlier in Sect. 4, it is possible that a third different más is required for certain phrasal que comparatives after all. If so, it is an open question whether the best analysis of (6) involves such a third type of standard marker or just más\(_{\textsc{clausal}}\). The scope data discussed below lends preliminary support for más\(_{\textsc{clausal}}\).

As Kennedy (1997) showed, DegP can never scope beyond a quantificational DP in subject position. This is known as the Kennedy/Heim Constraint: if the scope of a quantificational DP contains the trace of a DegP, it also contains that DegP itself. Moreover, Heim (2001) showed that not every scope ambiguity translates into a truth-conditional ambiguity, making putative scope movements of DegP hard to assess.

For this reason too, [D que] structures cannot be light headed relative clauses, in the sense of Citko (2004). Light headed relatives are relative clause constructions with a semantically “light” lexical head, usually a pronoun or demonstrative. Citko (2004: 98) provides the following example from Polish.

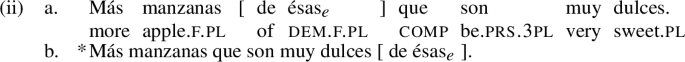

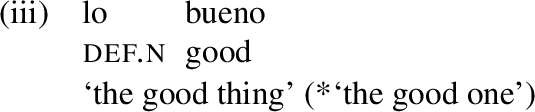

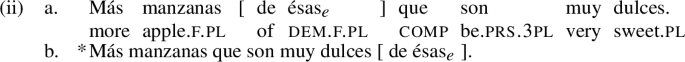

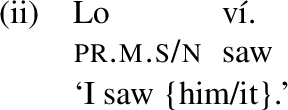

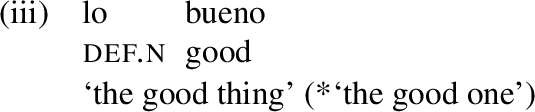

Spanish has similar constructions, formed by a demonstrative and a complementizer, like esos que (“these who”), or aquellos que (“those whose”). It seems that the kind of relative clauses appearing with de comparatives cannot be light headed relatives (see also Ojea 2013). Evidence comes from the [lo que] variant of the relative pronoun. One of the hallmarks of light headed relatives is that the demonstrative preceding the complementizer is invariably a pronoun (demonstrative or wh). However, lo in [lo que] constructions cannot be a pronoun, because pronoun lo is necessarily \([\pm\textsc{human}]\), whereas determiner lo is always \([-\textsc{human}]\):

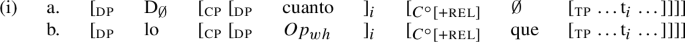

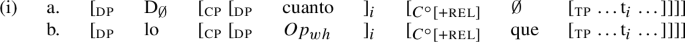

For simplicity, I assume that free relatives are bare CPs denoting a property of degrees, which are then “nominalized” by the application of a null D with the semantics of a max operator (Rullmann 1995; Caponigro 2002, a.m.o.). Nothing crucial hinges on this assumption. There is a plethora of syntactic approaches to free relatives that get to the same end I will later: that free relatives are interpreted as DPs. For instance, Mendia (2017) proposes a more articulated view where the [D que] cluster in free relatives is syntactically decomposed, and the task of the null max posited here is carried out by the overt D itself.

As long as both constructions are treated as free relatives denoting a maximal degree, the difference is not important for us.

The full derivation should include an assignment function to properly interpret the trace left behind by the relative pronoun, as well as the pronoun you. For simplicity, the trace is taken to contribute the degree that would otherwise be picked by said assignment function, and the correct representation of the pronoun is omitted.

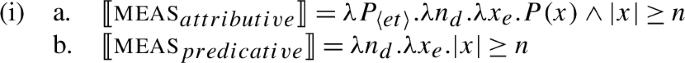

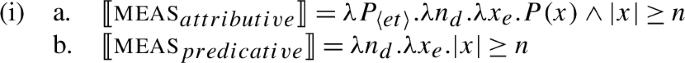

A second option is to provide two different definitions of meas, an attributive and a predicative version.

One could opt for other valency-reducing operations, but the choice requires further justification than I can offer here. For instance, one could adopt the type-shifter nom (or “∩”) from Dayal (2013) (based on Chierchia 1984). The type-shifter, however, maps properties onto their entity-correlates only if these exist. It is a matter of debate whether such entity-correlates exist for predicates like \(\lambda x_{e} . \vert x \vert \geq n\) (see Moltmann 2013: Section 6). For an objection against the iota type-shifter, see fn. 22.

For simplicity, I will only represent the existential quantifier when it is required to close the argument left open by Restrict. I am also ignoring other aspects that are irrelevant for comparatives, such as V to T movement. I assume the familiar operations of Functional Application (FA), Predicate Abstraction (PA) and Existential Closure (EC), as spelled out in Heim and Kratzer (1998); I note them by each line for readability.

If we were to close the DegP with ι in order to avoid applying Restrict, the resulting truth conditions would be of the form ate(Pedro, ιx[…x…]). These truth-conditions incorrectly require the existence of some specific unique set of apples that are greater in number to the apples that Juan brought, such that Pedro ate those apples. The truth-conditions, however, are too strong, as there need not be any specific or unique set of apples: any one set of apples that Pedro ate would suffice to render (72) true as long as the cardinality of the set is sufficiently big.

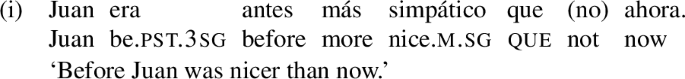

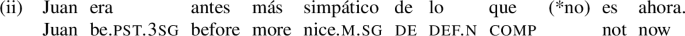

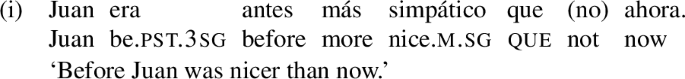

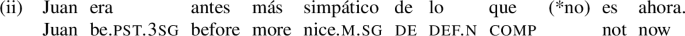

A further contrast between de and que comparatives involves the ability to host expletive negation (Sánchez López 1999; Aranovich 2007):

The source of the contrast seems to be syntactic since the expletive negative particle no is, by definition, not interpreted. Thus, the current analysis would be compatible with an account where the selectional restrictions of the preposition play a role in the distribution of negative expletives.

In this respect, Spanish should be added to the list of languages that lend support to recent claims that genuinely phrasal comparatives do exist in natural languages (cf. Bhatt and Takahashi 2011 on Hindi-Urdu). Moreover, as shown by Beck et al. (2010), Bhatt and Takahashi (2011) and others, different semantics for the comparative markers make different predictions about the kind of interpretations that we might expect from each comparative construction, as has also been shown to be the case in this paper.

Ultimately, everything hinges on (i) the DP status of Japanese comparatives like (92b) and on (ii) being able to ascribe a d-type denotation to headed relative clauses in Japanese. An in-depth exploration of the connection between Spanish de comparative constructions and Japanese yori clausal comparatives will have to wait, however, until a future occasion.

What is important to know about Degree Neuter Relatives for our current purposes is that they are nominal (e.g. Rivero 1981; Bosque and Moreno 1990) and denote degrees (e.g. Gutiérrez-Rexach 1999, 2014). Their exact internal composition is still a matter subject to discussion and I will not discuss it here (but see Mendia 2017).

For instance, a syntactic account of the ill-formedness of (96) would additionally have to explain why (90b), with a measure noun, is acceptable. Similarly, the semantic account faces the non-trivial task of explaining why “quantities of trouts” and “quantities of sardines” belong to different scales since, after all, this type of comparison is ubiquitous, not only in Spanish, but across languages.

References

Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Alrenga, Peter, and Chris Kennedy. 2014. No more shall we part: Quantifiers in English comparatives. Natural Language Semantics 22 (1): 1–53.

Alrenga, Peter, Chris Kennedy, and Jason Merchant. 2012. A new standard of comparison. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 30, eds. Nathan Arnett and Ryan Bennett. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Aparicio, Helena. 2014. A compositional analysis of subset comparatives. In Sinn & Bedeutung 18, eds. Urtzi Etxeberria, Anamaria Fălăuş, Aritz Irurtzun, and Brian Leferman.

Aranovich, Raul. 2007. Negative polarity and scalar semantics in Spanish. Lingvisticae Investigationes 30 (2): 181–216. https://doi.org/10.1075/li.30.2.03ara.

Bartsch, Renate, and Theo Vennemann. 1972. Semantic structures: A study in the relation between semantics and syntax. Frankfurt am Main: Athenaum.

Beck, Sigrid. 2011. Comparison constructions. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 1341–1389. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Beck, Sigrid, Vera Hohaus, and Sonja Tienmann. 2012. A note on phrasal comparatives. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 22, ed. Anca Chereches, 146–165.

Beck, Sigrid, Toshiko Oda, and Koji Sugisaki. 2004. Parametric variation in the semantics of comparison: Japanese and English. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 13 (4): 289–344.

Beck, Sigrid, Sveta Krasikova, Daniel Fleischer, Remus Gergel, Stefan Hofstetter, Christiane Savelsberg, John Vanderelst, and Elisabeth Villalta. 2010. Crosslinguistic variation in comparison constructions. In Linguistic variation yearbook 2009, ed. Jeroen van Craenenbroeck, Vol. 9, 1–66. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bello, Andrés. 1847. Gramática de la lengua castellana destinada al uso de los americanos, 3rd edn. Vol. 4 of Obras completas. Caracas: Imprenta del Progreso.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Soichi Takahashi. 2011. Reduced and unreduced phrasal comparatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 581–625.

Bierwisch, Manfred. 1989. The semantics of gradation. In Dimensional adjectives: Grammatical structure and conceptual interpretation, eds. Manfred Bierwisch and Ewald Lang, 71–261. Berlin: Springer.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1950. The comparison of inequality in Spanish. Language 26: 28–62.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1953. Addenda to “The comparison of inequality in Spanish”. Language 29: 62–66.

Bosque, Ignario, and Juan Carlos Moreno. 1990. Las construcciones con lo y la denotación del neutro. Lingüística, Revista de ALFAL 2 (1): 5–50.

Bresnan, Joan. 1973. Syntax of the comparative clause construction in English. Linguistic Inquiry 4 (3): 275–343.

Brucart, José María. 1992. Some asymmetries in the functioning of relative pronouns in Spanish. Catalan Working Papers in Linguistics 2: 113–143.

Brucart, José María. 2003. Adición, sustracción y comparación. In Actas del XXIII Congreso Internacional de Lingüística y Filología Románica, ed. Fernando Sánchez Miret, 11–60. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2002. Free relatives as DPS with a silent D and a CP complement. In Western Conference on Linguistics (WECOL) 2000, ed. Vida Samiian, 140–150.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2004. The semantic contribution of wh-words and type shifts: Evidence from free relatives crosslinguistically. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 24, ed. Robert B. Young, 38–55. Cornell University: CLC Publications.

Carlson, Gregory. 1977. Amount relatives. Language 53: 520–542.

Cecchetto, Carlo, and Caterina Donati. 2015. (Re)labelling heads. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1984. Topics in the syntax and semantics of infinitives and gerunds. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Chomsky, Noam. 1977. Conditions on transformations. In Essays on form and interpretation, 81–162. New York: Elsevier North-Holland, Inc.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra, and William A. Ladusaw. 2004. Restriction and saturation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Citko, Barbara. 2004. On headed, headless, and light-headed relatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22 (1): 95–126.

Cresswell, Max J. 1976. The semantics of degree. In Montague grammar, ed. Barbara H. Partee, 261–292. New York: Academic Press.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2013. On the existential force of bare plurals across languages. In From grammar to meaning: The spontaneous logicality of language, eds. Ivano Caponigro and Carlo Cecchetto, 49–80.

Gallego, Ángel J. 2013. Preposiciones de trayectoria y estructuras comparativas. In Las construcciones comparativas, eds. Luis Sáez and Cristina Sánchez López, 225–253. Madrid: Visor Libros.

Grant, Meghan. 2013. The parsing and interpretation of comparatives: More than meets the eye. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Grosu, Alexander, and Fred Landman. 1998. Strange relatives of the third kind. Natural Language Semantics 6 (2): 125–170.

Gutiérrez Ordóñez, Salvador. 1994a. Estructuras comparativas. Vol. 18 of Cuadernos de lengua española. Madrid: Arco Libros.

Gutiérrez Ordóñez, Salvador. 1994b. Estructuras pseudocomparativas. Vol. 19 of Cuadernos de lengua española. Madrid: Arco Libros.

Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier. 1999. The structure and interpretation of Spanish degree neuter constructions. Lingua 109: 35–63.

Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier. 2014. Interfaces and domains of quantification. Columbus: Ohio State University.

Hankamer, Jorge. 1973. Why there are two than’s in English. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 9, eds. Claudia Corum, T. Cedric Smith-Stark, and Ann Weiser, 179–191. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Hayashishita, J. R. 2009. Yori-comparative: Comments on Beck et al. (2004). Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18 (2): 65–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-009-9040-5.

Heim, Irene. 1985. Notes on comparatives and related matters. Ms., University of Texas at Austin.

Heim, Irene. 1987. Where does the definiteness restriction apply: Evidence from the definiteness of variables. In The representation of (in)definiteness, eds. Erik Reuland and Alice ter Meulen, 21–42. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heim, Irene. 2001. Degree operators and scope. In Audiatur vox sapientiae: A festschrift for Arnim von Stechow, eds. Caroline Fery and Wolfgang Sternefeld, 214–239. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden: Blackwell.

Herdan, Simona. 2008. Degrees and amounts in relative clauses. PhD diss., UConn.

Jacobson, Pauline. 1995. On the quantificational force of English free relatives. In Quantification in natural language, eds. Emmond Bach, Angelika Krazer, and Barbara H. Partee, 451–486. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Kennedy, Chris. 2002. Comparative deletion and optimality in syntax. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20 (3): 553–621.

Kennedy, Christopher. 1997. Projecting the adjective: The syntax and semantics of gradability and comparison. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Kennedy, Christopher. 1999. Projecting the adjective: The syntax and semantics of gradability and comparison. New York: Garland.

Kennedy, Christopher. 2009. Modes of comparison. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 43, eds. Malcolm Elliott, James Kirby, Osamu Sawada, Eleni Staraki, and Suwon Yoon, 141–165. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Lechner, Winfried. 2001. Reduced and phrasal comparatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19 (4): 683–735.

López, Luis. 2012. Indefinite objects. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McNally, Louis. 2004. Bare plurals in Spanish are interpreted as properties. Journal of Catalan Linguistics 3: 115–133.

Meier, Cécile. 2015. Amount relatives as generalized quantifiers. Available at http://user.uni-frankfurt.de/~cecile/PDF-files/AmountRelsNEW2015.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2019.

Mendia, Jon Ander. 2017. Amount relatives redux. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Merchant, Jason. 2009. Phrasal and clausal comparatives in Greek and the abstractness of syntax. Journal of Greek Linguistics 9: 49–79.

Moltmann, Friederike. 2013. Abstract objects and the semantics of natural language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morzycki, Marcin. 2011. Metalinguistic comparison in an alternative semantics for imprecision. Natural Language Semantics 19 (1): 39–86.

Morzycki, Marcin. 2016. Modification. Key topics in semantics and pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oda, Toshiko. 2008. Degree constructions in Japanese. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Ojea, Ana. 2013. A uniform account of headless relatives in Spanish. Language Sciences 40: 200–211.

Ordóñez, Francisco. 1997. Word order and clause structure in Spanish and other Romance languages. PhD diss., City University of New York.

Ormazabal Javier, Uriagereka Juan, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 1994. Word order and wh-movement: Towards a parametric account. Ms., U.Conn/UPV-EHU/UMD/MIT.

Ott, Dennis. 2011. A note on free relative clauses in the theory of phases. Linguistic Inquiry 42 (1): 183–192.

Pancheva, Roumyana. 2006. Phrasal and clausal comparatives in Slavic. In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 14, eds. James Lavine, Steven Franks, Mila Tasseva-Kurktchieva, and Hana Filip, 236–257. Ann Arbor: Slavic Publications.

Partee, Barbara. 1987. Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles. In Studies in discourse representation theory and the theory of generalized quantifiers 8, 115–143.

Partee, Barbara Hall. 1973. Some transformational extensions of Montague Grammar. Journal of Philosophical Logic 2: 509–534.

Pinkal, Manfred. 1989. Die Semantik von Satzkomparativen. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 8: 206–256.

Pinkham, Jessie E. 1982. The formation of comparative clauses in English and French. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Plann, Susan. 1984. The syntax and semantics of más/menos... que versus más/menos... de in comparatives of inequality. Hispanic Linguistics 1: 191–213.

Price, Susan. 1990. Comparative constructions in Spanish and French syntax. London: Routledge.

Prytz, Otto. 1979. Construcciones comparativas en español. Revue Romane 14 (2): 260–278.

Real Academia de la Lengua Española. 2010. Manual de la nueva gramática de la lengua española. Madrid: Espasa.

Reglero, Lara. 2007. On Spanish comparative subdeletion constructions. In Studia Lingüística 61, 130–169.

Rett, Jessica. 2014. The polysemy of measurement. Lingua 143: 242–266.

Rivero, María Luisa. 1981. Wh-movement in comparatives in Spanish. Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages 9: 177–196.

Rullmann, Hotze. 1995. Maximality in the semantics of wh-constructions. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Sáez, Luis, and Cristina Sánchez López. 2013. Las construcciones comparativas: Estado de la cuestión. In Las construcciones comparativas. Madrid: Visor.

Sáez del Álamo, Luis. 1999. Los cuantificadores: las construcciones comparativas y superlativas. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, Vol. 1, 1129–1188. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

Sánchez López, Cristina. 1999. La negación. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, 2561–2634. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

Schwarzschild, Roger. 2006. The role of dimensions in the syntax of noun phrases. Syntax 9: 67–110.

Seuren, Pieter A. M. 1978. The comparative. In Generative grammar in Europe, eds. Ferenc Kiefer and Ruwet Nicholas, 528–564. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Shimoyama, Junko. 2012. Reassessing crosslinguistic variation in clausal comparatives. Natural Language Semantics 20 (1): 83–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-011-9076-8.

Solé, Yolanda. 1982. On más / menos ... que versus más / menos ... de comparativespania. Hispania 65: 614–619.

Solt, Stephanie. 2014. Q-adjectives and the semantics of quantity. Journal of Semantics 32 (2): 221–273.

Stassen, Leon. 1985. Comparison and Universal Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell Sci.

Sudo, Yasutada. 2015. Hidden nominal structures in Japanese clausal comparatives. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 24 (1): 1–51.

von Fintel, Kai. 1999. Amount relatives and the meaning of chains. Cambridge: MIT Press. Available at http://web.mit.edu/fintel/fintel-1999-amount.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2019.

von Stechow, Arnim. 1984. Comparing semantic theories of comparison. Journal of Semantics 3 (1–2): 1–77.

Wellwood, Alexis. 2015. On the semantics of comparison across categories. Linguistics and Philosophy 38 (1): 67–101.

Wunderlich, Dieter. 2001. Two comparatives. In Perspectives on semantics, pragmatics, and discourse: A festschrift for Ferenc Kiefer, eds. István Kenesei and Robert M. Harnish, 75–91. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Acknowledgements

For comments and helpful discussions, I am grateful to Athulya Aravind, Rajesh Bhatt, Jeremy Hartman, Vincent Homer and three anonymous NLLT reviewers. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendia, J.A. One more comparative. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 581–626 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09454-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09454-x