Abstract

While there is anecdotal evidence and some scientific support for the value of having multiple paths to reach one’s life goals, recent work concerning backup plans argues that their mere availability undermines commitment to and performance in the originally chosen path. In this paper, we evaluated this phenomenon amongst college students (N = 345) entering their first term with an already available family-based alternative life path. As expected, entering into college with an available family-based alternative life path led to a decrease in study commitment over the first semester and indirectly predicted lower end-of-semester grades through this reduction in commitment. However, results indicate that this only occurred when students reported experiencing an action crisis at the end of their first semester. If students did not report having an action crisis, an available family-based alternative life path did not influence study commitment and predicted a higher end-of-semester GPA. Ultimately, findings highlight the major role action crisis plays in the influence an alternative life path has on path trajectory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

How one finds fulfillment in their life is a difficult issue that everyone must tackle. Some may argue that they find fulfillment mainly from the products of their career and the lasting legacy they leave behind through their achievements. Others might argue that their fulfillment comes more from time spent with their family and the bonds they foster at home (Twenge & King, 2005), or some combination of the two. Individuals do not simply choose what they derive fulfillment from but evolve and explore different options to find fulfillment throughout their life (Baumann & Ruch, 2022). Thus, one usually will pursue a specific path to find fulfillment (e.g., pursue career-oriented or family-oriented goals) but leave other paths in reserve in case their current path does not provide the fulfillment they seek. However, the influence of alternative life paths—different routes leading toward the same overarching goal of living a fulfilling life (Napolitano et al., 2021)—on one’s current path trajectory is understudied, and interestingly, research from two different perspectives holds contrasting predictions about the functionality of alternative life paths.

On the one hand, it has been argued that it is wise to have a ‘safety net’ in the form of a Plan B in case Plan A fails. For example, the self-complexity model proposes that having a diverse, multi-dimensional self-concept buffers the negative impact of stress on well-being (Linville, 1987; Rafaeli-Mor & Steinberg, 2002). Similarly, the two-process framework of goal pursuit suggests that having substitutability in personal goals facilitates disengagement in the face of high difficulties and constrains (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002). Moreover, goal-systems theory outlined that commitment to and the perceived attainability of an overarching goal is strengthened by the availability of multiple, substitutable paths (Kruglanski et al., 2011). To sum, several theories propose that having some sort of safety net in one’s means-goal-structure facilitates higher-order goal pursuit and buffers against adversity.

On the other hand, recent research on backup plans highlights possible limitations and downsides of available alternatives. Specifically, research suggests that holding a backup plan may reduce instrumentality of and commitment to continue using the first-choice plan and, in fact, undermine goal pursuit and attainment (Napolitano & Freund, 2016, 2017; Napolitano et al., 2021, 2022; Hoff & Napolitano, 2023).

On initial review, one could conclude that the two lines of research are in stark contrast to one another, one arguing in favor of and the other against alternative-life paths. This paper aims to illustrate that both types of findings are in fact compatible and that they result from the same basic mechanism. In line with the two-process framework of goal pursuit (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002), we suggest that having an alternative path facilitates disengagement, specifically when goal-striving does not go well, that is, when difficulties accumulate and a person experiences an action crisis (Brandstätter et al., 2013).

Alternative life paths

Alternative life paths are defined as different routes that a person could take towards achieving abstract goals such as living a good life or being a good person (Veenhoven, 2000). By route, we mean that one’s current path and one’s alternative life path are means that are both perceived to lead to the same abstract ends (i.e., they are equifinal; Kruglanski et al., 2002; Kruglanski et al., 2011). By different, we mean that taking an alternative life path would substantially alter a person’s everyday behaviors (see Ullmann-Margalit, 2006 for a similar discussion on “big decisions”). Finally, by could take, we mean that alternative life paths are available options for the person. To be available, alternative life paths must be practically possible; they are not free fantasies (Oettingen, 2012). But they must also be societally-sanctioned or acceptable to pursue. Following goal hierarchy theory (Powers, 1973), we assert that life paths are program goals developed by people to reach their higher-order principal goal of living a fulfilling life. In this theorization, life paths are not only goals within themselves but also means used to achieve the principal goal of living a fulfilling life.

Family-based alternative life paths

For this research, we look at a specific kind of alternative life path: reducing the focus placed on one’s job – temporarily or permanently – to focus on caring for a family. We call these family-based alternative life paths: to live a fulfilling life, a person could imagine either finding their fulfillment primarily through their career or through their family, and we assume the amount of focus placed on either path indicates the fulfillment they perceive they can derive from it.

The present research aims to illustrate the effects an available family-based alternative life path can have on students during their first semester of college. We do not make normative assumptions about whether a family-based alternative life path should be preferred over a career-oriented one or vice versa. Some people may prefer one to the other, others may see both as equally enticing, and for some, preferences may change over time. But because we are investigating how alternative life-paths influence path trajectory in first-semester university students, we will assume that pursuing a career is indeed their primary life path, at least for the moment, and having a family is an alternative life path or one they will pursue later in life.

We aimed to highlight how having a family-based alternative life path when entering college can influence a student’s path trajectory. Previous research on the related construct of backup plans (Napolitano et al., 2021) suggests that having an available alternative life path when entering college results in disengagement (lower commitment) and thus lower end-of-semester grades. In the following section we will briefly describe the theory and evidence supporting this hypothesis.

Alternative life-paths as backup plans

Backup plans are “alternative means to an end that are intentionally developed but not initially (or ever) used” (Napolitano & Freund, 2016, p. 56). When inviting guests for dinner, one might buy a jar of mayonnaise in case they do not have time to make homemade mayonnaise. Backup plans are not initially used, but are instead reserved until either a contingency situation arises (e.g. the egg yolks curdle), or until the backup plan grows more useful than the first-choice plan (e.g. you think your time would be better spent tidying the house instead of preparing homemade mayonnaise).

The work on the “backup plan paradox” by Napolitano and Freund (2017) argues that the creation and retention of a backup plan can diminish commitment to one’s first-choice plan. This reduced commitment undermines goal pursuit and heightens the probability of transitioning to the reserved plan. Through a series of studies, Napolitano and Freund (2017) demonstrated that investing in a backup plan increases the probability of its utilization, even if the outcome would be more favorable by adhering to the first-choice plan.

For example, in a study by Nijenkamp and colleagues (2016), participants allocated less time to study for the first attempt in a college exam when they had the option to repeat it. In another study, participants donated less money to a humanitarian organization fighting child hunger when they were presented with both the means of donating money and signing a petition compared to when they were presented with the means of donating money only (Bélanger et al., 2015, Study 5).

To sum, research concerning backup plans has consistently argued that holding such a secondary plan in reserve undermines the perceived utility and commitment to the first-choice plan. Given the conceptual similarity between backup plans and alternative life paths, it is possible that a family-based alternative life path can undermine students’ study commitment over time. However, we suggest that when exploring the relationship between alternative life paths and goal-commitment it is important to consider a crucial moderator. As theorizing on self-complexity and the two-process framework on goal-pursuit outlined, having a multidimensional self and substitutable goals can provide positive benefits in the face of stress and difficulties during goal striving (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002; Linville, 1987).

Thus, we propose that having an alternative plan undermines utility and commitment particularly when difficulties and setbacks arise during goal striving along a first-choice plan. As these difficulties and setbacks accumulate, people start to deliberate if disengaging from the current plan is a wise option (Brandstätter et al., 2013). If a second option is already available, in the form of a backup plan, the burden associated with disengaging from one’s current plan is lessened making disengagement more “palatable”. In contrast, if setbacks and difficulties do not accumulate during goal striving, the reduced utility and commitment of a first-choice plan are unlikely to occur.

Setbacks during goal pursuit and action crisis

Rooted in the action-phase model of goal-striving (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987; Gollwitzer et al., 1990), Brandstätter and colleagues proposed that when setbacks and failure accumulate, people start to doubt and question their goal-commitment (Brandstätter & Herrmann, 2016; Ghassemi et al., 2017). In this state, known as an action crisis, an individual is thrown from a goal-focused implemental mindset, which facilitates goal-striving, back into a deliberative mindset, wherein cost-benefit analysis takes precedence over goal implementation (Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013; Keller et al., 2019). This means a person starts to reconsider and re-evaluate the desirability and attainability of a focal path comparing it with available alternatives (see Vann et al., 2018, for a nuanced analyses of mechanisms).

Given that students with an available alternative life path possess two authentic self-aspects that can be directly compared, they should find it relatively easier to disengage from their current path when experiencing an action crisis. This is because a viable alternative is already present, and the advantageous effects associated with an implemental mindset have been dismantled. This heightened disengagement tendency is expected to manifest in reduced commitment to the current path. Thus, while having an available alternative life path may reduce commitment to one’s first-choice path (i.e., a life focused on a career), this should only be the case when difficulties and setbacks accumulate to the level of an action crisis.

Current study

This research aimed to test two hypotheses concerning the influence the availability of a family-based alternative life path has on students during their first semester in college. First, we predict that the presence of an action crisis moderates the relationship between the availability of a family-based alternative life path and change in study commitment during one’s first semester in college (Hypothesis 1). Second, we tested trickle-down relationships with end-of-semester grades. Specifically, we predicted that the availability of a family-based alternative life path when entering college would lead to lower end-of-semester grades through a moderated mediation effect, with the presence of an action crisis playing the role of moderator and study commitment acting as a mediator (Hypothesis 2).

To test our proposed hypotheses, we conducted a longitudinal study among first-semester students at a German university. The longitudinal design had two time points. Time 1 occurred at the beginning of the semester, and Time 2 occurred three months later, shortly before the exam period. During each time point, participants completed an online questionnaire designed to measure their current perceptions of the availability of a family-based alternative life path, study commitment, and the presence of an action crisis.

Methods

Sample

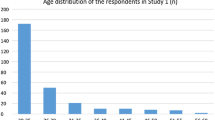

We aimed for a sample of at least 311 students to find our hypothesized effect that the availability of a family-based alternative life path would alter path trajectory through one’s first semester in college, as calculated by G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) using a small effect size of f2 = 0.02, an alpha of 0.05, and aiming to reach a power of 80%. The questionnaire at Time 1 was completed by 442 students to help insulate the final sample against attrition. Of the 442 students, 373 completed the questionnaire at Time 2. We excluded students who failed a quality check item in at least one time point (n = 13), as well as students in graduate programs (n = 15) resulting in a final sample of 345 students. Of those, 160 were female and 183 male; two students indicated their gender as diverse. Students were young on average: Age ranged from 17 to 51 years, with 82.34% being 20 years old or younger (M = 19.93, SD = 3.62).

Measures

Family-based alternative life path

Items assessing alternative life paths have to contain an if-then structure. They do not simply ask whether participants want to have a family or whether they anticipate failure on their current path. It is crucial that they refer to the contingency between anticipated failure and a family-based alternative. Accordingly, each item asks whether respondents have a family-based life path idea (i.e., staying at home with kids) in case their current career path fails.

We used a German translation of three items created by Napolitano et al. (2021) to assess the availability of a family-based alternative life path – holding a life path focused on family in reserve in case the current path does not produce life fulfillment – on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree (e.g., “Staying at home with kids is a possible alternative for me if I’m not successful in my career”; αt1 = 0.86 and αt2 = 0.89).

Study commitment

To assess study commitment, we adapted a 5-item scale measuring goal commitment by Klein and colleagues (2001). We asked participants to think of the goal of successfully completing their current study program and let them rate the items (e.g. “I am strongly committed to pursuing this goal.”) with that goal in mind on a 5-point scale (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree; αt1 = 0.81, αt2 = 0.84).

Action crises

The experience of action crises was measured by six items developed by Brandstätter and Schüler (2013). Four items (e.g. “I keep on ruminating about my studies.”) were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = does not apply at all to 5 = totally applies, two additional items (e.g. “How often have you had the impulse to give up your studies lately?”) were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very frequently (αt1 = 0.80, αt2 = 0.82).

End-of-semester grades

Consent for the collection of end-of-semester GPAs from the university registrar was provided by 286 students at Time 1, 240 of whom completed both time points. In addition to this, the final high school grade of each student was collected at Time 1 to account for any baseline differences in GPA when entering college.

Results

All data, syntax files, and copies of all utilized measures can be found in our open access online repository: https://osf.io/tqzs2/?view_only=a6482532aad34e85b0ea63fd071418e1.

Preliminary analyses

To ensure there was no difference between participants who completed both time points and those who only completed Time 1, we conducted attrition analyses on all of our main variables of interest. Analysis determined no group differences existed between participants who only completed Time 1 and those who completed both time points in any of the core study variables at T1, F(1,440) < 0.34, p > .566.

Due to the possible higher social acceptance for women to utilize a family-based life path, we completed analyses to determine if any group differences existed between the male and female participants in our sample on the main variables of interest. Analysis determined no group differences existed between males and females in any of the core study variables at T1, F(1,341) < 0.96, p > .329Footnote 1.

Finally, in order to understand the relationships among the variables of interest within our sample, we computed correlations between each variable of interest at T1 and T2. These correlations, along with the mean and standard deviation of each variable, can be located in Table 1.

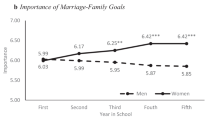

The moderating effect of an action crisis

To test whether perceiving an action crisis at T2 moderated the link between family-based alternative life paths at T1 and change in study commitment we utilized a hierarchical multiple regression. The hierarchical multiple regression revealed that the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 (ß = -0.13, p = .006, 95% CI [-0.22, -0.04]) and the perception of an action crisis at T2 (ß = -0.48, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.57, -0.38]) contributed significantly to the regression model, F(2,342 = 54.01, p < .001 and accounted for 24.0% of the variation in change in study commitment. Introducing the interaction variable to the regression model explained an additional 1.6% of the variation and this change in R² was significant, F(1,341) = 7.36, p = .007. Simple slope analysis revealed significant effects of a family-based alternative life path on study-related commitment when students experienced mean levels of action crises, ß = -0.13, p = .004, 95% CI [-0.23, -0.04], or one standard deviation above mean levels, ß = -0.26, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.39, -0.13]. However, when students experienced one standard deviation below mean levels of action crises, study commitment was not impacted by an available family-based alternative life path, ß = -0.01, p = .829, 95% CI [-0.14, 0.11] (Fig. 1).Footnote 2

Examining trickle-down effects

Under guidelines by Edwards and Lambert (2007), we developed a first stage moderated mediation path model to test trickle-down effects hypotheses. Specifically, we tested whether the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 (independent variable) will directly affect GPA (dependent variable), while indirectly affecting GPA through change in study commitment (mediator variable). Finally, we predicted that the relationship between the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 and change in study commitment would be moderated by the presence of an action crisis at T2. To control for previous performance, we residualized GPA, i.e. we predicted students’ GPA with their high school grades and utilized the standardized residuals as our GPA variable in the analysis.Footnote 3

The model was found to support our predictions (Fig. 2). Specifically, the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 predicted a decrease in study commitment (ß = -0.14, p = .004, 95% CI [-0.23, -0.04]), and this reduction in study commitment was moderated by the presence of an action crisis at T2 (ß = -0.13, p = .006, 95% CI [-0.22, -0.04]). Furthermore, the reduction in study commitment predicted a lower GPA (ß = 0.26, p < .001, 95% CI [0.14, 0.04]). Overall, a significant indirect effect existed between the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 and GPA through the moderated mediation effects of study commitment and the presence of an action crisis (ß = -0.04, p = .017, 95% CI [-0.06, -0.01]). Finally, we found that the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 predicted a higher GPA (ß = 0.17 p = .008, 95% CI [0.05, 0.30]) when the moderated mediated effect of action crisis and study commitment were controlled for (Fig. 2). This positive direct effect was not hypothesized.

First stage moderated mediation path model of the availability of a family-based alternative life path at T1 on GPA through the mediator study commitment and the moderator of the presence of an action crisis at T2. GPA has been residualized to control for the influence of final high school grade. Study commitment has been residualized to control for the influence of T1 study commitment. * indicates a p < .050

Discussion

The findings presented here support the idea that the availability of a family-based alternative life path might shape university students’ professional trajectories. The findings support our assumption derived from backup plan research that having such a “safety net,” in the form of a family-based alternative life path, can reduce one’s commitment to their chosen path (Bélanger et al., 2015; Napolitano & Freund, 2016, 2017; Napolitano et al., 2021, 2022). However, our results suggest a more nuanced understanding of the timing and utility of this reduced commitment.

Backup plan research hypothesizes a systematic reduction in path commitment amongst all participants with a family-based alternative life path. The present research expands this perspective by demonstrating that the experience of an action crisis moderates the relationship between an available family-based alternative life path and reductions in study commitment. Participants who reported no signs of action crisis, indicating that setbacks and difficulties during goal-striving were low, sustained their goal commitment even when endorsing a family-based alternative life path. These results are in line with theorizing that suggests a buffering effect self-complexity and substitutability of goals in the face of difficulty (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002; Linville, 1987). The availability of an alternative path seems to facilitate disengagement in the face of accumulating adversity, i.e., when students start question their focal path.

Our results fit within the theoretical framework of action crisis theory (Brandstätter et al., 2013), which suggests that an accumulation of setbacks and adversity may produce a shift in action phase related mindset. Specifically, students who experience difficulties (e.g., when failing exams) will at one point leave an implemental mindset (focus on pursuing and shielding a focal goal) and start deliberating the feasibility and desirability of their goal. Previous research suggests that this deliberative mindset is characterized by open-minded cognition and evaluation of all behavioral options (Fujita et al., 2007; Gollwitzer et al., 1990). Our research showed that, indeed, students who experience an action crisis seem to consider available alternatives. Having an alternative life path available made them more likely to disengage from the study related focal goal. In sum, even though we did not assess mindsets in the present research, our findings provide indirect evidence for the deliberative mindset suggestion of action crisis theory.

Interestingly, an available family-based alternative life path predicted a reduction in study commitment at high as well as only moderate levels of action crisis. This result suggests that some amount of doubting one’s goals (even below the scale mid-point) might be sufficient to bring about a shift in mindset, triggering deliberation on a focal goal and making possible alternatives influential. The shift from an implemental to a deliberative mindset is proposed as a core characteristic of an action crisis (Brandstätter et al., 2013). However, the exact tipping points for action crises and deliberative mindsets have yet to be empirically established. Our data suggest that even a few or mild doubts about one’s path might initiate a shift in mindset, which makes further deliberation and consideration of possible alternatives more likely.

Importantly, the magnitude of an action crisis does not have to reflect the magnitude of experienced adversity. Individuals will differ regarding the number of setbacks and the level of adversity that will trigger doubt in their focal goal. For example, students with a growth mindset (Dweck, 1999) or individuals high in action orientation (Kuhl, 1992) might intensify their effort after experiencing failure without experiencing an action crisis. For these individuals, even a moderate level of action crisis might indicate already accumulated experiences of setbacks. Future research needs to develop precise models that attempt to predict what levels of adversity result in an action crisis and what levels of action crisis indicate a shift towards a deliberative mindset.

The present study explored the direct and trickle-down effects a family-based alternative life path has on actual path performance. The subsample of students who provided information on their grades revealed a notable finding that is consistent with research concerning the possible benefits of having a “safety net” and theorization concerning backup plans’ detrimental effects on path commitment. On the one hand, there was a positive direct relationship between the availability of a family-based alternative life path and grades. On the other hand, the results of our path model illustrated that the availability of a family-based alternative life path indirectly predicted worse end-of-semester grades through its relationship with study commitment. Importantly, both effects existed even when controlling for both T1 study commitment and high school grades.

While these contrasting findings for the direct and indirect effects of the availability of a family-based alternative life path could seem contradictory upon initial review, the results fit within our theoretical framework. Specifically, we argue that an alternative life path has a multifaceted influence on goal-striving by facilitating goal-disengagement in an action crisis while having beneficial effects in the absence of an action crisis. On the one hand, when people experience an action crisis, having an alternative life path can make the prospect of disengaging from the current path more palatable as an alternative is already available to fill the role of the current path. On the other hand, having an alternative life path seems to facilitate path performance in people who do not show any signs of action crisis.

We believe our finding of the positive facilitation effect alternative life paths had on path performance is theoretically consistent with the findings that self-complexity improves coping strategies (Koch & Shepperd, 2004) and buffers against stress-related illness and depression (Linville, 1987). Building on these findings, it makes theoretical sense to assume that having multiple alternative life paths can help to facilitate path performance by reducing stress and improving coping strategies. However, as we did not hypothesize the facilitation finding, critical measures to test this assumption were not included in the study design (e.g. stress, coping strategies). Due to the post hoc nature of this argument, we urge readers to interpret it cautiously until future studies can replicate the effect and illustrate the mediating roles of stress and coping strategies in the phenomenon.

We have viewed our particular research question through the lens of school success as the primary life path and a family as an alternative life path. However, we do not make any judgment about success or failure from these results. This study aims to detail the precise mechanisms at work concerning alternative life paths and the effects they have on commitment. The findings of this research could be viewed as either positive or negative depending on the viability of each life path for the individual. The lower study commitment seen here would be negative if it is a byproduct of premature doubts leading to disengagement from a path that would have led to fulfilment. On the other hand, research on action crises highlights how this disengagement can be considered a positive outcome (Ghassemi et al., 2017). Specifically, if an individual was mobilizing effort towards a path that was unsuited for finding fulfillment, the availability of a family-based alternative life path has facilitated disengagement saving resources, alleviating stress, and allowing them to pursue and feel confident in their alternative life path as a more appropriate means to achieve their desired goal more quickly (Brandstätter & Herrmann, 2016).

Future directions

This paper unilaterally focuses on the influence backup plans have on commitment and does not investigate the additional influence they can exert in incurring extra costs during the goal-striving process. Research on the backup plan paradox has also argued that the development, monitoring, and updating of backup plans come with costs (Napolitano & Freund, 2017). In the case of a family based alternative life path this “costs” likely involve investing time and resources in romantic relationships or children. Some students may experience a resource-based conflict between studies and family-related life, e.g., when studying involves living in a different city separated from their partner or family or when scares time must be divided between the two life areas. It is possible that students with a family-based alternative life path are more likely to experience such a conflict. However, romantic relationships are also an important source of social support (House, 1981; Weber et al., 2004) and students may even experience mutual facilitation between their studies and their family-oriented goals, e.g., when dating a fellow student (Riediger & Freund, 2004; Wiese & Salmela-Aro, 2008). In sum, the role of possible costs or benefits associated with a family-based alternative life path might be complex and should be investigated in future research.

This research marks the initial step in integrating mindset concepts into the domain of alternative life paths, opening doors for future investigations into the interplay between various mindsets and backup plans. Specifically, the comparison mindset, a mindset stemming from comparative thinking that influences decision-making even in contexts beyond the original comparison’s scope (Xu & Wyer, 2008), emphasizes the potential impact of different mindsets on the backup plan and alternative life path literature, given that comparison is at the heart of this phenomenon. While our current study does not directly delve into the relationship between mindsets and alternative life paths, it underscores the need for future research to consider the influence of mindsets in this context.

Conclusion

Taken together, the present study provides consistent evidence that the availability of a family-based alternative life path can influence the professional trajectories of first-year college students. This effect is twofold. Under specific circumstances, an available alternative life path facilitates disengagement and, in turn, leads to lower performance. Moreover, the direct positive relationship with performance shows a more complex constellation of influences. Perceiving engagement in a family as a viable alternative to a professional career can help first-year students to understand the viability of an academically oriented life path.

Notes

Due to the lack of group differences, the relatively small sample, and the aim of this paper to illustrate the global effect of the phenomenon we have decided to not report hypothesis testing for male and female participants in the main text of the paper.

To pinpoint the precise tipping point at which an action crisis reached a level to produce a negative influence of alternative life paths on goal commitment, we conducted a floodlight analysis employing the Johnson-Neyman technique. The findings revealed that when action crises were situated at 0.33 standard deviations below the mean level, alternative life paths began to exert a detrimental impact on goal commitment (ß = -0.10, p = .050, 95% CI [-0.19, 0.00]).

To ensure the residualization process did not create spurious findings, we also completed the moderated mediation model with GPA scores that are not residualized with high school grades. All results reported remained statistically significant (p < .016) and the magnitude of effects remained consistent (|ß| > 0.15).

References

Baumann, D., & Ruch, W. (2022). What constitutes a fulfilled life? A mixed methods study on lay perspectives across the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.982782.

Bélanger, J. J., Schori-Eyal, N., Pica, G., Kruglanski, A. W., & Lafrenière, M. A. K. (2015). The more is less effect in equifinal structures: Alternative means reduce the intensity and quality of motivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 60, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.05.005.

Brandstätter, V., & Herrmann, M. (2016). Goal disengagement in emerging adulthood: The adaptive potential of action crises. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415597550.

Brandstätter, V., & Schüler, J. (2013). Action crisis and cost–benefit thinking: A cognitive analysis of a goal-disengagement phase. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.004.

Brandstätter, V., Herrmann, M., & Schüler, J. (2013). The struggle of giving up personal goals: Affective, physiological, and cognitive consequences of an action crisis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(12), 1668–1682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213500151.

Brandtstädter, J., & Rothermund, K. (2002). The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two-process framework. Developmental Review, 22(1), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2001.0539.

Dweck, C. S. (1999). Caution‐praise can be dangerous. American Educator, 23, 4–9.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., et al. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Fujita, K., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Oettingen, G. (2007). Mindsets and pre-conscious open-mindedness to incidental information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.004.

Ghassemi, M., Bernecker, K., Herrmann, M., & Brandstätter, V. (2017). The process of disengagement from personal goals: Reciprocal influences between the experience of action crisis and appraisals of goal desirability and attainability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(4), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216689052.

Gollwitzer, P. M., Heckhausen, H., & Steller, B. (1990). Deliberative and implemental mind-sets: Cognitive tuning toward congruous thoughts and information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1119–1127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1119.

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992338.

Hoff, B. F., & Napolitano, C. M. (2023). Can investing in backup plans harm adolescents’ goal performance? Initial evidence from a quasi-experimental study. Current Psychology.

House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Keller, L., Bieleke, M., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2019). Mindset Theory of Action Phases and If-Then planning. In K. Sassenberg, & M. L. W. Vliek (Eds.), Social psych in action (pp. 23–38). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13788-5.

Klein, H. J., Wesson, M. J., Hollenbeck, J. R., Wright, P. M., & Deshon, R. P. (2001). The assessment of goal commitment: A measurement model meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85(1), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2931.

Koch, E. J., & Shepperd, J. A. (2004). Is self-complexity linked to Better Coping? A review of the literature. Journal of Personality, 72, 727–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00278.x.

Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Fishbach, A., Friedman, R., Chun, W. Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal systems. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 34, pp. 331–378). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80008-9.

Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., & Sheveland, A. (2011). How many roads lead to Rome? Equifinality set-size and commitment to goals and means. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(3), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.780.

Kuhl, J. (1992). A theory of self-regulation: Action versus state orientation, self-discrimination, and some applications. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 41(2), 97–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1992.tb00688.x.

Linville, P. W. (1987). Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related Illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.663.

Napolitano, C. M., & Freund, A. M. (2016). On the use and usefulness of backup plans. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615596991.

Napolitano, C. M., & Freund, A. M. (2017). First evidence for the backup plan paradox. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(8), 1189–1203. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000331.

Napolitano, C. M., Michael, S., Walton, G. M., & Job, V. (2021). Who has the choice? The availability of a family-based alternative life path undermines mothers’ career motivation. Manuscript in Preparation.

Napolitano, C. M., Kern, J. L., & Freund, A. M. (2022). The backup planning scale (BUPS): A self-reported measure of a person’s tendency to develop, reserve, and use backup plans. Journal of Personality Assessment, 104(4), 496–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2021.1966021.

Nijenkamp, R., Nieuwenstein, M. R., De Jong, R., & Lorist, M. M. (2016). Do resit exams promote lower investments of study time? Theory and data from a laboratory study. Plos One, 11(10), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161708.

Oettingen, G. (2012). Future thought and behaviour change. European Review of Social Psychology, 23(1), 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2011.643698.

Powers, W. T. (1973). Feedback: Beyond Behaviorism. Science, 179(4071), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.179.4071.351.

Rafaeli-Mor, E., & Steinberg, J. (2002). Self-complexity and well-being: A review and research synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_2.

Riediger, M., & Freund, A. M. (2004). Interference and facilitation among personal goals: Differential associations with Subjective Well-being and persistent goal pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(12), 1511–1523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271184.

Twenge, J. M., & King, L. A. (2005). A good life is a personal life: Relationship fulfillment and work fulfillment in judgments of life quality. Journal of Research in Personality, 39(3), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2004.01.004.

Ullmann-Margalit, E. (2006). Big decisions: Opting, converting, drifting. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, 58, 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1358246106058085.

Vann, R. J., Rosa, J. A., & McCrea, S. M. (2018). When consumers struggle: Action crisis and its effects on problematic goal pursuit. Psychology & Marketing, 35(9), 696–709. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21116.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The Four qualities of Life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010072010360.

Weber, K., Johnson, A., & Corrigan, M. (2004). Communcating emotional support and its relationship to feelings of being understood, trust, and self-disclosure. Communication Research Reports, 21(3), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090409359994.

Wiese, B. S., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2008). Goal conflict and facilitation as predictors of work–family satisfaction and engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.09.007.

Xu, A. J., & Wyer, R. S. (2008). The comparative mind-set. Psychological Science, 19(9), 859–864. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02169.x.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Christopher Mlynski and Swantje Mueller Shared first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mlynski, C., Mueller, S., Napolitano, C.M. et al. A backup plan for life? Alternative Life paths facilitate disengagement in an action crisis. Motiv Emot 48, 66–74 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-023-10052-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-023-10052-z