Abstract

Self-determination theory proposes that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs is equally beneficial for everyone – the Universal Hypothesis. Equally, there are intra-individual differences in how the satisfaction of differentially important needs might be differentially beneficial, which we term the Intra-individual Hypothesis. We aimed to reconcile these positions. Across four cross-sectional studies (ns = 300 rock climbers, 323 sportspeople, 394 UK and Chinese adults, 320 UK adults), we investigated the needs of individuals with varying dimensions to their identity, and their motivation and self-esteem. In Studies 1, 2, and 4, when individuals strongly related their sense of identity to investment in a specific activity, the association between need satisfaction and self-esteem (and motivation in Studies 1–2) depended on their intra-individual need importance, supporting the Intra-individual Hypothesis. In Studies 3 and 4, for individuals with a multidimensional identity, the association between need satisfaction and self-esteem did not depend on the importance of each need, supporting the Universal Hypothesis. The satisfaction of basic psychological needs is not always uniform in its link with motivation and well-being. The degree to which individuals have a unidimensional or multidimensional self-concept appears fruitful in predicting the relative value of the Universal Hypothesis and the Intra-individual Hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2002) is a theory of human motivation that has three innate basic psychological needs at its core: the need for autonomy – to feel volitional and responsible for one’s behavior; the need for competence – to feel effective in bringing about desired outcomes; and the need for relatedness – to feel securely connected to and understood by others. Integral to self-determination theory is that these needs are equally beneficial to everyone – the Universal Hypothesis.

There is an ongoing debate in the needs and motives literature as to whether these needs may be individually varied rather than universal. According to this individual view, people with comparatively strong needs will benefit more from experiencing satisfaction of such needs (see Schüler, Brandstätter, & Sheldon, 2013). Attempts to reconcile the universal versus individual position have been equivocal (see Sheldon & Schüler, 2019). Importantly, these reconciliatory attempts have been across two distinct motivational paradigms; namely Self-determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; the universal view) and Motive Disposition Theory (McClelland, 1965; the individual view).

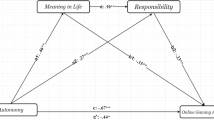

Across four studies, we aim to reconcile the universal and individual views within a single theoretical framework: self-determination theory. Specifically, we aim to incorporate the individual view into self-determination theory by investigating individuals’ intra-individual need importance (i.e., people’s relative need importance across their own basic psychological needs). The overarching hypothesis is that when individuals attach more importance to satisfaction of a specific need, they will glean the greatest psychological benefit when that specific need is satisfied. We term this the Intra-individual Needs Importance Hypothesis, hereafter simply the Intra-individual Hypothesis. We also aim to explore the impact of individuals’ sense of identity on the relative explanatory value of the Universal Hypothesis and the Intra-individual Hypothesis. To derive self-esteem, a person with a unidimensional identity (i.e., a sense of self based on a single activity/role) is more reliant on this single identity than a person with a multidimensional identity (i.e., a sense of self based on multiple activities/roles). As such, when any given psychological need is not met by an activity/role, a person with a multidimensional identity has the opportunity to use other activities/roles to compensate for this loss. Our overarching hypothesis is that the satisfaction of an intra-individually important need will be more closely related to a person’s self-esteem when that person has a unidimensional identity compared to a person with a multidimensional identity. Consistent with previous research on self-determination theory, we explore the relationship between the satisfaction of different needs and self-determined motivation, self-esteem, and depression. Importantly, we test each hypothesis nomothetically and idiographically, as the Intra-individual Hypothesis is an idiographic hypothesis. Specifically, for the idiographic analyses, we match each intra-individual need importance with its corresponding relationship with motivation, depression, and self-esteem.

The universal hypothesis

Central to self-determination theory is that basic psychological needs are universal (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2002). That is, the benefits of need satisfaction are equal for each need and for all people regardless of individual differences in the strength of each need (Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). According to the Universal Hypothesis, each need must be fulfilled for psychological health to occur; if any one of the three needs is unfulfilled, psychological health will suffer (e.g., Chen et al., 2015; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Sheldon & Schüler, 2011). Equally, the satisfaction of a strong need will be no more beneficial than the satisfaction of a weaker need. Given this universal view, self-determination theorists’ empirical focus has been on the effects of need satisfaction rather than on relative need strength. Adopting this stance, research has provided support for the value of basic need satisfaction in predicting self-determined motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Self-determination theory has also generated a substantial volume of research on the effects of need satisfaction on a wide range of psychological well-being outcomes such as vitality, life satisfaction, and self-esteem across many life domains and cultures (e.g., Chen et al., 2015; Thøgersen-Ntoumani & Ntoumanis, 2007). Further, research has shown that need frustration is associated with depressive symptoms (Chen et al., 2015).

Studies that have examined the claim that basic needs are universally beneficial for motivation have yielded supportive albeit inconsistent findings. For example, motive disposition research has shown support for the universal benefits of need satisfaction on motivation (Sheldon & Schüler, 2011). This work shows that those who report not wanting a particular need (i.e., low motive disposition for that need) experience positive affect just as much from having the corresponding basic need (i.e., satisfying that need) as those who report wanting the need (i.e., high motive disposition for that need). Other research shows only limited support for moderator effects. For example, Wörtler et al. (2020) found only slight evidence for the moderating role of need strength in the relationship between work-related need satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (see also Schüler et al., 2013). In summary, the Universal Hypothesis has more evidence for it than against it.

The individual view

Personality theorists (e.g., Hofer & Busch, 2011) have argued for the examination of individual differences in need strength because such differences might influence the relationship between need satisfaction and psychological well-being, thus matching the individualized motive disposition view with self-determination theory. According to this Matching Hypothesis (Sheldon & Schüler, 2019; Schüler et al., 2013), individuals with a comparatively strong motive will benefit more from experiencing satisfaction of a matching need. Some research on motive dispositions has demonstrated support for this Matching Hypothesis. By matching self-determination theory’s basic needs to the motives studied in motive disposition theory (i.e., power, achievement, and affiliation; McClelland, 1965), this research revealed that individuals with a strong motive for a particular experience glean greater motivation benefits from satisfaction of the basic psychological need that corresponds to that type of experience (Schüler & Kuster, 2011; Schüler, Sheldon, & Frölich, 2010). Specifically, Schüler and colleagues found that individuals with strong motives for power (Schüler et al., 2013, 2016), achievement (Schüler, Sheldon, & Frölich, 2010), and affiliation (Schüler & Brandstätter, 2013) gleaned greater motivation benefits from corresponding feelings of autonomy, competence and relatedness, respectively. These findings seem to suggest that the motivational benefits of need satisfaction are at least partly driven by individual differences. However, although some researchers argue that the needs that underpin the universality view are conceptually similar to implicit motives, self-determination theorists (Chen et al., 2015; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020) have argued that the motives in motive disposition theory and the basic needs in self-determination theory are underpinned by different theoretical concepts and are thus conceptually incompatible.

There is sparse research that examines how the relative strength of basic needs might differentially affect the link between need satisfaction and general psychological well-being. Schüler and colleagues found some support regarding the relationship between need strength and domain-specific well-being, but the findings were not replicated for general well-being (Schüler et al., 2013, 2016; Sheldon & Schüler, 2011). There is some experimental research that has revealed a moderating influence of individual differences in the need for competence on the relationship between competence satisfaction and well-being (Neubauer, Lerche, & Voss, 2018). Also, a recent study showed that the effects of autonomy satisfaction and frustration on well- and ill-being, respectively, were not significant for individuals who had a low desire for autonomy (Van Assche, van der Kaap-Deeder, Audenaert, Schryver, & Vansteenkiste, 2018). The authors concluded, however, that the interaction effects were modest compared to the relative variance explained by need satisfaction or need frustration main effects. Other research has shown no support for the moderating effects of need strength on general well-being (Chen et al., 2015). In summary, support for the individual view is equivocal.

The intra-individual hypothesis

Self-determination theorists (Chen et al., 2015; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020) have suggested that the most appropriate way to examine need importance is via an explicit assessment of how much people value or desire the satisfaction of their basic needs. We agree with that view. Accordingly, we propose to use an explicit conceptualization of need importance (i.e., how important is the satisfaction of this need for you?) as used in previous research (e.g., Chen et al.). The Intra-individual Hypothesis is that people will glean the greatest psychological benefit when their more important psychological needs are satisfied. This is an idiographic (within-person) hypothesis. To date, researchers have not tested this hypothesis. Indeed, researchers have limited their investigative view of relative need importance to a nomothetic lens (Chen et al.; Flunger et al., 2013; Katz et al., 2010) despite the idiographic vs. nomothetic debate having evolved in other domains such as self-esteem (Hardy & Leone, 2008; Lindwall et al., 2011; Marsh, 1995; Pelham & Swann, 1989). For example, when Chen et al. examined explicit need importance as a moderator of the relationship between need satisfaction and general well-being, they found that participants benefited from satisfaction of their needs regardless of how much importance they attributed to each need, seemingly debunking the individual view. However, Chen et al.’s design and analyses were a nomothetic test of an inter-individual view and were not intended to test our Intra-individual Hypothesis, which requires an intra-individual analysis.

As is common in moderated hierarchical regression analyses, Chen et al. (2015) created need satisfaction × importance interaction terms for each of the three basic needs. In using a Structural Equation Model to analyze these cross products as possible indicators of moderation in the need satisfaction – well-being relationship, they operationalized individual differences in need importance nomothetically (between individuals). As such, the hypothesis was: if Need 1 is more important for Person A than for Person B, then the satisfaction of Need 1 will be more beneficial for Person A than it will be for Person B. However, such a nomothetic approach could not capture the central tenet of the Intra-individual Hypothesis; namely, that such individual differences are idiographic. Specifically, this hypothesis is: if Need 1 is more important than Need 2 for Person A, then the satisfaction of Need 1 will be more beneficial than the satisfaction of Need 2 for Person A.

We propose that relative need importance, when operationalized nomothetically, will not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation (Hypothesis 1), or between need satisfaction and self-esteem (Hypothesis 2). That is, the nomothetic view will confirm the Universal Hypothesis (cf. Chen et al., 2015). Conversely, when operationalized idiographically, the satisfaction of more important needs will predict a larger proportion of variance in self-determined motivation (Hypothesis 3) and self-esteem (Hypothesis 4) than will the satisfaction of less important needs. That is, the idiographic view will support the Intra-Individual Hypothesis. We addressed the tension between the Universal and Intra-individual hypotheses in this way across four studies.

Dimensionality of identity

One can derive self-esteem from one’s self-concept, which can be more or less multidimensional (Rogers, 1959). Although some people consider themselves to possess a truly multidimensional self-concept (e.g., mother, friend, worker, daughter, and tennis player), others consider themselves to possess a rather more unidimensional self-concept (e.g., rock climber). Furthermore, need satisfaction gained via an activity of extreme importance and prevalence is likely to contribute more to a person’s global self-esteem than need satisfaction gained via other less important daily life activities (Hardy & Moriarty, 2006). This idea is consistent with recent research that found that super-elite athletes (i.e., serial Olympic medal winners) perceived their participation in sport to be their only important motive – far more important than their engagement in other aspects of life such as interpersonal relationships (Hardy et al., 2017; Rees et al., 2016). For individuals with such a unidimensional sense of identity, satisfaction of their (intra-individually) more important needs will likely be more beneficial to motivation and self-esteem. Indeed, when people allocate most of their resource to a single life domain, there remains little opportunity to compensate for unsatisfied needs via other life domains. Conversely, individuals whose identity is dependent on multiple domains have every opportunity to compensate for any unmet needs via engagement in other life domains, such that satisfaction of more or less important needs will likely not have differential effects on psychological well-being.

This dimensionality framework leads to the overarching hypothesis that the dimensionality of the self will determine the degree to which one will find support for the Universal Hypothesis or the Intra-individual Hypothesis. Specifically, when investigating individuals with a multidimensional sense of identity, one will find support for the Universal Hypothesis (Hypothesis 5). When investigating individuals with a unidimensional sense of identity, one will find support for the Intra-individual Hypothesis (Hypothesis 6). We make some assumptions about identity dimensionality across Studies 1–3 and we test these hypotheses directly in Study 4.

Study 1

Our initial examination of these questions was within the context of sport participation (cf. Schüler et al., 2016). Specifically, participants in Study 1 were high-performing individuals who were highly committed to their participation in the specific activity of rock climbing. We chose rock climbing, as research has shown that high-risk sport participants have a somewhat addictive attitude to their sport, which provides a fruitful condition for a relatively unidimensional identity (see Barlow et al., 2013; Woodman et al., 2009).

Participants

From an original sample of 377 rock climbers, we selected 337 rock climbers on the basis that their ability ranged from highly competent to professional athlete. This selection was to ensure that rock-climbing formed a meaningful part of their identity. The final sample comprised 300 participants (n = 218 men; 82 women; Mage = 27.03 years; SD = 9.00).

Measures

Need importance

We designed the Basic Need Importance Scale to measure the importance that individuals attach to the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs. To this end, we adapted the Basic Need Satisfaction in General Scale (BNS-G; Gagné, 2003) by asking participants to consider the importance of each statement (rather than the satisfaction of each statement) in relation to their life. We used only the 12 positively worded items because the negatively phrased items did not reflect the introductory importance paragraph. These items measured three subscales: autonomy (n items = 4; e.g., I feel like I am free to decide for myself how to live my life); competence (n items = 3; e.g., most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from what I do); and relatedness (n items = 5; e.g., people I interact with on a daily basis tend to take my feelings into consideration), on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all important) to 7 (very important).

Need satisfaction

We used the Basic Need Satisfaction at Work Scale (BNS-W; Deci et al., 2001) to measure the extent to which participants felt that their basic psychological needs were satisfied by rock-climbing. The BNS-W comprises 21 items that assess the satisfaction of the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. We replaced the word work with climbing for all items (e.g., “most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from climbing”). The Likert scale ranges from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true).

Self-determined motivation

The Sport Motivation Scale (SMS-II: Pelletier et al., 2013) comprises 18 items that assess participants’ motivation toward sport. We replaced the word sport with climbing for all items (e.g., “because climbing reflects the essence of whom I am”). The SMS-II includes six regulation subscales on a Likert scale from 1 (does not correspond at all) to 7 (corresponds completely): amotivation; external motivation; introjected motivation; identified motivation; integrated motivation; and intrinsic motivation. We calculated self-determined motivation using the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) following the procedure by Vallerand et al. (2008): ∑ [(amotivation × (-3)) + (external × (-2)) + (introjected × (-1)) + (identified × (+ 1)) + (integrated × (+ 2)) + (intrinsic × (+ 3))]. Higher scores reflect greater self-determined motivation.

Self-esteem

We used Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item Self-Esteem (RSE) inventory. Participants responded to statements (e.g., “I have certainly felt useless at times”) on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). This inventory has been widely used as an indicator of well-being in the self-determination theory literature (e.g., Chen et al., 2015).

Procedure

We combined all inventories into an online survey (Qualtrics, 2011). We invited participants to take part in the study via advertisements posted in climbing groups on social media websites, online climbing forums, and on websites hosted by major climbing brands. On the first page of the questionnaire, participants indicated informed consent and then completed demographic questions regarding their climbing history. Participants then completed the following sequence of questionnaires: the need importance scale (in general life), the adapted BNS-W (i.e., satisfaction of basic needs in climbing), the adapted SMS-II scale (i.e., self-determined motivation for participation in climbing) and the RSE scale (general self-esteem). We instructed participants to think about their participation in climbing before responding to questions on the BNS-W and SMS-II scales, then instructed participants to think about their life in general when responding to questions about their self-esteem.

Analyses

In the first phase of analysis we examined the factorial validity of the basic psychological need importance scale developed specifically for the study, using Bayesian structural equation modelling (BSEM; Asparouhov, Muthén & Morin, 2015). In the second phase we examined Hypotheses 1–4.

Hypothesis-testing strategy

For this section of analyses, we used manifest variables. For each BSEM, we used a non-informative prior distribution in estimation. That is, we made no specifications for the prior point estimates or the distribution of the parameters in question (cf. Kruschke, 2013). To check model convergence, we specified a fixed number of 50,000 iterations for two MCMC chains and inspected the PSR values. We also performed visual examination of the trace plots for each parameter.

We analyzed the data using two different analytical procedures. First, we analyzed the data from a nomothetic (between-person) approach. Three separate BSEM models (i.e., one model for each basic need) for each criterion variable estimated the effects of need importance as a moderator in the relationship between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation and self-esteem. For each model, we report the unstandardized estimates (cf. Friedrich, 1982; Jaccard et al., 1990).

Second, we analyzed the data using an intra-individual difference approach adopting the analytical procedure from the self-esteem literature (Hardy & Moriarty, 2006). Specifically, to test the effects of within-person differential importance of the three basic psychological needs, we identified the basic need satisfaction scores for the most important, the second most important and the least important needs for each participant. Separate BSEM models for each criterion variable then estimated the satisfaction scores of the most, second most and least important needs as predictors of self-determined motivation and self-esteem.

Results

Factorial validity

We retained a 10-item three-factor need importance scale of autonomy (n items = 3), competence (n items = 2), and relatedness (n items = 5). BSEM indicated that the probability of this model was excellent with a PPp of 0.52, CI [-32.96, 31.06]. All major loadings were significant and acceptable. Composite reliability coefficients (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) for the three subscales were: autonomy, 0.89; competence, 0.86; and relatedness, 0.92.

Descriptive statistics

The need importance means (SD) were: most important need, 6.07 (0.61); second most important need, 5.47 (0.69); least important need, 4.69 (1.00). Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness positively correlated with self-determined motivation and self-esteem (see Table 1). Satisfaction scores of the most important, second most important, and least important basic needs were also significantly and positively related to self-determined motivation and self-esteem.

Self-determined motivation

Nomothetic need importance analysis

Adequate convergence was achieved for all BSEM models: PSR values reached the convergence criterion in the first 1000 iterations and visual inspection of the trace plots showed a stable convergence across iterations for the two chains. Symmetric 95% posterior predictive confidence intervals and PPp values indicated excellent fit for self-esteem and self-determined motivation: autonomy, 95%Footnote 1 CI [-9.29, 9.33], PPp = 0.50; competence, CI [-9.09, 9.10], PPp = 0.50; relatedness, CI [-9.08, 9.33], PPp = 0.50. Satisfaction of all three basic psychological needs significantly predicted self-determined motivation (RAI): autonomy; R2 = 0.16, p < 0.001; b = 8.54, p < 0.001; CI [6.10, 11.02]; competence; R2 = 0.11, p < 0.001; b = 4.21, p < 0.001; CI [1.79, 6.66]; relatedness; R2 = 0.24, p < 0.001; b = 11.09, p < 0.001; CI [8.86, 13.35]. There were no significant interactions between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy, competence or relatedness on self-determined motivation: autonomy, b = -0.24, CI [-2.24, 1.81]; competence, b = -0.35, CI [-2.10, 2.76]; relatedness, b = -1.37, CI [-3.63, 0.87].

Idiographic need importance analysis

300 (89%) participants reported within-person importance differences across the three psychological needs. We removed from analysisFootnote 2 participants who failed to record three different need importance scores. The models achieved adequate convergence; PSR values reached the convergence criterion in the first 1000 iterations and visual inspection of the trace plots showed a stable convergence across iterations for the two chains. Symmetric 95% posterior predictive confidence intervals and PPp values indicated excellent model fit for self-determined motivation and self-esteem, CI [-9.22, 9.47], PPp = 0.50. Satisfaction of the most and second most important needs significantly predicted variance in self-determined motivation, R2 = 0.26, p < 0.001; bs = 10.05 and 8.18, ps < 0.001, CIs [6.66, 13.52] and [4.85, 11.52], respectively. However, satisfaction of the least important need did not predict self-determined motivation, b = -0.30, CI [-3.64, 3.09]. Furthermore, the beta coefficients decreased in order of importance (i.e., from most important need to least important need).

Self-esteem

Nomothetic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of each psychological need significantly predicted self-esteem: autonomy, R2 = 0.10, p < 0.001; b = 1.36, p < 0.001; CI [0.72, 1.96]; competence, R2 = 0.07, p < 0.001; b = 0.83, p < 0.05; CI [0.30, 1.49]; relatedness, R2 = 0.10, p < 0.001; b = 1.68, p < 0.001; CI [1.10, 2.26]. There were no significant interactions between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy, competence or relatedness on self-esteem.

Idiographic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of the most and second most important needs significantly predicted variance in self-esteem, R2 = 0.12 p < 0.001; bs = 1.23 and 1.14, ps < 0.01, CIs [0.34, 2.13] and [0.28, 2.01], respectively. Satisfaction of the least important need did not predict self-esteem, b = 0.70, CI [-0.17, 1.57]. The beta coefficients again decreased in order of importance (i.e., from most important to least important need).

Discussion

The aim of Study 1 was to examine whether the satisfaction of differentially important psychological needs would be differentially associated with self-determined motivation and self-esteem. When we considered the data nomothetically, need importance did not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation or self-esteem, as hypothesized (see Chen et al., 2015). Conversely, as hypothesized, when we considered the data idiographically, satisfaction of the more important needs significantly predicted self-determined motivation and self-esteem; satisfaction of the least important need did not. Furthermore, the association between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation and self-esteem increased as need importance increased. These findings support the Intra-individual Hypothesis and suggest that the associations between basic need satisfaction and both motivation and self-esteem are dependent on the intra-individual importance attached to the fulfilment of a specific need.

Study 2

The first aim of Study 2 was to re-test Hypotheses 1 and 2 (nomothetic operationalization of need importance) in a broader population of recreational sport participants, whose identity was more likely to be multidimensional. Specifically, for such a recreational sample, one would expect the idiographic hypothesis to hold for self-determined motivation for the chosen recreational activity (i.e., a domain-specific motivation), but not for self-esteem more globally. That is, given the recreational nature of participation, one would expect participants to be able to glean self-esteem from sources that extend beyond their recreational activity. The second aim of Study 2 was to re-examine Hypotheses 3 and 4, that satisfaction (gained via sport) of more important needs would predict a larger proportion of variance in self-determined motivation and general self-esteem than the satisfaction of less important needs.

Participants

Participants were 417 recreational and club-level individuals who took part in a wide range of individual and team sports (e.g., football, kayaking, running, basketball, skiing, netball, canoe polo). The final sample comprised 323 participants (n = 205 men; 118 women; Mage = 27.78 years; SD = 10.48).

Measures

Need importance

To measure need importance, we used the 10-item Basic Need Importance Scale from Study 1, with the addition of three more competence items from the BNS-G (Gagné, 2003), which we worded positively (e.g., “In my life I get chances to show how capable I am”). We added these items to address the concern over the small number of competence items in Study 1.

Need satisfaction

We administered the 20-item Basic Needs Satisfaction in Sport Scale (BNSSS; Ng et al., 2011) to assess the satisfaction of each basic psychological need in the sport context (e.g., “I can overcome challenges in my sport”). We asked participants to focus on one sport when responding. Items are scored on a Likert Scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true).

Self-determined motivation

We used the SMS-II to measure participants’ motivation for sport. As with the need satisfaction scale, we asked participants to focus on a single sport when responding to statements about their motivation for sport.

Self-esteem

We again used Rosenberg’s (1965) general self-esteem scale.

Procedure

The procedure for this study was the same as in Study 1, with two alterations: (a) the use of the BNSSS to measure need satisfaction and (b) a demographic section tailored to assess participants’ general sports history and experience. We asked participants to select a single sport for consideration when answering questions related to sport participation, need satisfaction, and self-determined motivation; we asked them to think about their general life when responding to questions about need importance and self-esteem.

Analyses

The first phase of the analysis examined the factorial validity of the basic psychological need importance scale. The second phase examined Hypotheses 1–4.

Hypothesis-testing Strategy

Given the two hierarchical levels (the individual and the sport), we analyzed the data using multi-level BSEM. In the current study the individual level (i.e., Level 1) was of primary interest. Consequently, all data were group mean centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). We first analyzed the data using a nomothetic approach; specifically, using three BSEM models (i.e., one model for each basic need) for each criterion variable, we tested Hypotheses 1 and 2. Second, we analyzed the data using an idiographic approach. Specifically, we tested Hypotheses 3 and 4 using a BSEM model for each criterion variable.

Results

Factorial Validation of the Need Importance Measure

We retained an 11-item need importance scale. BSEM indicated that the probability of this model was excellent with a PPp of 0.51, CI [-35.77, 34.56]. All major loadings were significant and acceptable. Composite reliability coefficients were: autonomy (n items = 3), 0.89; competence (n items = 3), 0.88; and relatedness (n items = 5), 0.93.

Descriptive statistics

The need importance means (SD) were: most important need, 5.61 (0.61); second most important need, 5.18 (0.64); least important need, 4.73 (0.73). Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness positively correlated with self-determined motivation and self-esteem (see Table 2), as did satisfaction of the most important, second most important, and least important basic needs.

Self-determined motivation

Nomothetic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of each psychological need significantly predicted self-determined motivation: autonomy; R2 = 0.26, p < 0.001; b = 10.29, p < 0.001; CI [7.62, 12.94]; competence, R2 = 0.25, p < 0.001; b = 10.67, p < 0.001; CI [8.02, 13.34]; relatedness, R2 = 0.10, p < 0.001; b = 5.76, p < 0.001; CI [2.91, 8.62]. There were no significant interactions between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy, competence or relatedness on self-determined motivation.

Idiographic need importance analysis

323 participants (77%) reported within-person differences in importance of psychological needs. Satisfaction of the most and second most important needs significantly predicted self-determined motivation, R2 = 0.25 p < 0.001; bs = 0.31 and 0.20, ps < 0.001; CIs [0.21, 0.40] and [0.09, 0.30], respectively; satisfaction of the least important need did not, b = 0.09, CI [-0.02, 0.20]. Beta coefficients decreased in order of importance (i.e., most to least).

Self-esteem

Nomothetic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of autonomy and competence significantly predicted self-esteem: autonomy; R2 = 0.10, p < 0.001; b = 0.69, p < 0.05; CI [0.00, 1.39]; competence; R2 = 0.16, p < 0.001; b = 2.25, p < 0.001; CI [1.59, 2.91]; satisfaction of relatedness did not, R2 = 0.04, b = 0.43, CI [-0.25, 1.13]. There were no significant interactions between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy, competence or relatedness on self-esteem.

Idiographic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of the second most important need significantly predicted self-esteem, R2 = 0.10, p < 0.001; b = 0.22; p < 0.001;

CI [0.10, 0.33]; satisfaction of the most and least important needs did not, bs = 0.04 and 0.07; CIs [-0.08, 0.16] and [-0.05, 0.18], respectively.

Discussion

Results from the nomothetic analysis again showed that basic psychological need importance did not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation or self-esteem, as hypothesized. The idiographic analyses of Study 2 replicated those of Study 1. As hypothesized, satisfaction of the more important needs predicted self-determined motivation; satisfaction of the least important need did not. Again, the association between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation increased as need importance increased.

The association between the relative importance of need satisfaction and self-esteem appears rather more random. One potential explanation for the consistent findings with self-determined motivation, but more random findings with self-esteem, resides in the extent to which the participants in each study identify themselves by their chosen sport. The participants in Study 1 were highly committed to rock-climbing. As such, their participation in this activity was likely to be highly related to their sense of identity. Consequently, one would expect need satisfaction (via climbing) to be a significant contributor to these individuals’ overall self-esteem (cf. Hardy & Moriarty, 2006). In contrast, participants in Study 2 took part recreationally in a wide array of sports. In other words, these participants’ self-identity was likely less invested in a single sport. As such, if engagement in a particular activity (sport) does not satisfy one’s more important psychological needs, then one has an opportunity to compensate for this by engaging in other activities.

Study 3

In Study 3, we aimed to extend further the specific conditions that might be ripe for supporting the Universal Hypothesis by extending the sampling to a broad population across two cultures. We sampled the participants in Study 3 from a wider population of individuals across two different cultures (UK and Asia). Consequently, we used and validated the need importance scale that Chen et al. (2015) used in their cross-cultural research. The main aim of Study 3 was to extend Study 1 and 2 by examining how need satisfaction in general life might be linked with self-esteem and depression (see Chen et al.). Participants in Study 3 rated the satisfaction of their basic psychological needs in relation to their general life. As such, their responses were based upon many life domains and many aspects of self-identity and so should support the Universal Hypothesis for self-esteem regardless of whether one considers the data nomothetically or idiographically.

Participants

Participants were 442 individuals from the UK and Singapore. All participants were fluent English speakers. The final sample comprised 394 individuals (Mage = 32.7 years; SD = 12.53) from the UK (n = 223; 123 men, 100 women; 214 Caucasian; 9 mixed race, Mage = 32.01 years; SD = 11.54) and Singapore (n = 171; 71 men, 100 women; 146 Chinese, 17 Asian, 4 mixed ethnicity, 4 other ethnic group; Mage = 33.58 years; SD = 13.71).

Measures

Need importance

To measure need importance, we used the English version of the need importance scale developed by self-determination theorists to assess basic need importance across different cultures (Chen et al., 2015; Sheldon & Gunz, 2009). We chose this scale specifically for Study 3 because of its previous use in cross-cultural research (cf. Chen et al.) and to replicate more closely that approach. The need importance scale comprises 12 items across 3 subscales: autonomy (n items = 4); competence (n items = 4); relatedness (n items = 4). Respondents rated how important it is to satisfy each of the basic needs on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important to me). Example items include: how important is it for you to feel: “…that your choices express who you really are” (autonomy); “…confident that you can do things well” (competence); “…close and connected with other people who are important to you” (relatedness).

Basic need satisfaction

We used the Basic Need Satisfaction in General Scale (BNS-G; Gagné, 2003), which contains 12 positively worded items and 9 negatively worded items across autonomy (n items = 7), competence (n items = 6), and relatedness (n items = 8) on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true).

Self-esteem

As in the previous studies, we used Rosenberg’s (1965) scale.

Depression

We measured depressive symptoms with the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). We asked participants to consider each item in relation to feelings over the past week. Example items include “my sleep was restless” and “I felt fearful”. Items were measured on a Likert scale from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time).

Procedure

We invited people to take part in the research via email, advertisements on social media websites and a wide array of online fora. On the first page of the online questionnaire, participants indicated informed consent and then completed demographic questions. Demographic questions asked participants to indicate their country of residence, ethnicity, age and sex. Before participants responded to each questionnaire in the survey, we asked them to think about their general life.

Analyses

The preliminary analysis examined the factorial validity of Chen et al.’s (2015) basic need importance scale. The main analyses examined Hypothesis 1 (nomothetic; well-being) and 2 (idiographic; well-being) using the analytical procedures from Studies 1 and 2.

Hypothesis-testing strategy

In order to replicate Chen et al.’s (2015) approach, we considered well-being as a combination of self-esteem and depression. We included culture as a covariate.

Results

Factorial validity of the need importance measure

BSEM indicated excellent probability of a 10-item three-factor need importance scale, PPp = 0.52, CI [-37.65, 37.22]. All major loadings were significant and acceptable. Composite reliability coefficients were: autonomy, 0.92; competence, 0.94; and relatedness, 0.95.

Descriptive statistics

The need importance UK/Singapore means (SD) were: most important need, 4.51 (0.49)/4.48 (0.49); second most important need, 4.14 (0.53)/4.20 (0.53); least important need, 3.75 (0.62)/3.81 (0.55). Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness positively correlated with self-esteem and negatively correlated with depression (see Table 3). Satisfaction of the most important and least important basic needs were also positively correlated with self-esteem and negatively correlated with depression. Only the most important and least important needs were examined as predictors of well-being in this study, as 394 participants (89%) reported two or more different importance ratings for the basic psychological needs, but only 200 participants (45%) reported differences across all three needs. This lack of differentiation points to a sensitivity issue with the need importance scale in this study.

Well-being (self-esteem and depression)

Nomothetic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness predicted well-being: autonomy; R2 = 0.52, p < 0.001; b = 3.32, p < 0.001; CI [2.86, 3.78]; competence; R2 = 0.59, p < 0.001; b = 3.87, p < 0.001; CI [3.46, 4.29]; relatedness; R2 = 0.33, p < 0.001; b = 2.71, p < 0.001; CI [2.13, 3.19]. There were no significant interactions between satisfaction and importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness on well-being.

Idiographic need importance analysis

We computed the mean intra-individual importance score for each basic need. For participants who reported one basic need as more important and two basic needs as less important, one of the less important needs was randomly assigned as the least important need, and vice versa. Satisfaction of the most and least important needs each significantly predicted well-being, R2 = 0.60 p < 0.001; bs = 2.20 and 2.90; ps < 0.001; CIs = [1.44, 2.93] and [2.11, 3.70], respectively.

Discussion

The main aim of Study 3 was to examine the interaction between basic need importance and satisfaction on psychological well-being (self-esteem and depression) in general life. Regardless of whether the data were treated nomothetically or idiographically, the importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness did not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction and well-being. These findings offer support for the Universal hypothesis.

Study 4

Studies 1 and 2 provided support for the Intra-individual Hypothesis. That is, satisfaction of intra-individually more important needs predicted self-determined motivation (in rock-climbing and in a specific sport), and satisfaction of the less important needs did not. For self-esteem, the Intra-individual Hypothesis held only when we considered that participants had a relatively unidimensional sense of identity (rock climbers in Study 1). However, we did not specifically measure this sense of identity. In Study 4, we sought to measure participants’ sense of identity regarding their engagement in specific activities with the expectation that a multidimensional self-concept would provide support for the Universal Hypothesis and that a unidimensional self-concept would provide support for the Intra-individual Hypothesis. As such, the main aim of Study 4 was to confirm the findings from Study 1 across a wide selection of highly identified specific activities. We aimed to test this identity hypothesis by investigating people who: (a) felt that their sense of identity was dependent on a single activity/role; or (b) felt that they had a multidimensional sense of identity.

Method

Participants

We recruited 447 individuals from the general population across the UK. The final sample comprised 320 participants: Unidimensional identity, n = 110, 58 men, 52 women, 31 career, 54 sport, 25 parent; Mage = 42.81 years, SD = 11.87; and Multidimensional identity, n = 210, 86 men, 124 women, Mage = 44.67 years, SD = 13.19.

Measures

Sense of identity

Participants reported if they felt they had (a) an identity that was strongly related to a single activity or role (i.e., a unidimensional identity) or (b) an identity that was not strongly related to a single activity or role (i.e., a multidimensional identity). We applied decomposition techniques (Kessler et al., 2003) to improve response accuracy and we developed questions using items from the Athlete Identity Measurement Scale (AIMS; Brewer & Cornelius, 2001), replacing sport words with activity/role (e.g., the essence of who I am is strongly dependent on a single activity/role; I define myself by a single activity/role). The opening paragraph informed participants that each statement described a person whose sense of identity was dependent on a single activity/role. Participants responded to each statement on a scale of 1 (not like me at all) to 6 (very much like me). We then asked On the whole, do these statements describe how you feel about your sense of identity? to which participants responded by selecting either Yes, on the whole, these statements are like me or No, on the whole, these statements are not like me. Participants who selected Yes… described their identity with one or two words (e.g., doctor, triathlete).

Activity/role identity

To confirm participants’ self-selected unidimensional identity, we used the Athlete Identity Measurement Scale (AIMS; Brewer & Cornelius, 2001), replacing sport with activity/role (e.g., this activity/role is the most important part of my life, I typically organize my day so that I can take part in this activity/role). Participants responded on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Only participants who reported a unidimensional identity completed the AIMS (Alpha = 0.79). We retained participants only if their mean identity score was greater than 4.0.

Need importance

We used the 11-item Basic Need Importance Scale (Studies 1–2).

Need satisfaction

We used two need satisfaction questionnaires to measure need satisfaction. Participants who rated themselves as having a unidimensional identity completed an adapted version of the Basic Need Satisfaction in Sport Scale (BNSSS) used in Study 2. In the opening paragraph of this scale we instructed participants to answer the questions while thinking of the activity/role they had specified. We replaced sport with activity/role (e.g., most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from this activity/role). Participants who rated themselves as having a multidimensional identity completed the Basic Need Satisfaction in General Scale (BNS-G) used in Study 3

Self-determined motivation

We used the SMS-II to measure participants’ motivation toward their specific activity/role. Only participants who reported themselves as having a unidimensional identity completed this measure. We replaced sport with activity/role (e.g., because this activity/role reflects the essence of whom I am). We removed one item (because I find it enjoyable to discover new performance strategies) because we could not adapt it to be relevant to all potential activities/roles.

Procedure

We invited participants via advertisements posted in domain-specific groups and fora and through email lists. On the first page of the questionnaire, participants indicated informed consent and completed demographic questions. We then asked participants to think about the different activities that they took part in across their life, which could include the activities associated with work (e.g. academic, business executive, nurse, teacher, etc.), sport (e.g. footballer, triathlete, mountaineer, etc.), music (singer, pianist, violinist, etc.), at home (e.g. mother, father, grandparent, etc.), etc. Next, participants completed the preliminary identity decomposition questions, and reported having either a unidimensional or multidimensional identity. The online inventory then branched off into one of two directions depending on the participant’s identity response.

Participants who reported having a unidimensional identity completed the following sequence of questionnaires: the need importance scale (in general life), the activity/role identity scale (i.e., how much they identified with their reported activity/role), the adapted BNSSS (satisfaction of basic needs within their reported activity/role), the SMS-II (self-determined motivation within their activity/identity), the RSE scale (self-esteem in general life) and the CES-D scale (depression in general life). Participants who reported having a multidimensional identity completed the following sequence of questionnaires: the need importance scale (in general life), the BNS-G scale (need satisfaction in general life), the RSE scale (self-esteem in general life), and the CES-D scale (depression in general life).

Main analyses

The analyses for the current study were split into two parts. In Part 1 we analyzed the unidimensional identity data. Specifically, as in Study 1, we examined Hypothesis 1 (nomothetic; self-determined motivation), Hypothesis 2 (nomothetic; well-being), Hypothesis 3 (idiographic; self-determined motivation), and Hypothesis 4 (idiographic; well-being), using the same analytical procedure described in the previous studies.

In Part 2 we analyzed the multidimensional identity data. Specifically, we examined Hypothesis 5: when relative need importance is operationalized nomothetically, need importance will not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction (gained via all life domains) and well-being; and Hypothesis 6: when need importance is operationalized idiographically, satisfaction (gained via all life domains) of the intra-individually more and less important needs will predict a similar proportion of variance in general well-being. We examined these new hypotheses using the same analytical procedure described in Study 3. As in Study 3, we created a latent variable well-being from the combination of self-esteem and depression (cf. Chen et al., 2015).

Part 1

We first analyzed the unidimensional identity data nomothetically; three BSEM models (i.e., one model for each basic need) for each criterion variable (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Second, we analyzed the data idiographically with one BSEM model for each criterion variable (Hypotheses 3 and 4).

Part 2

We analyzed the multidimensional identity data nomothetically using three BSEM models (Hypothesis 5), and idiographically using one BSEM model (Hypothesis 6).

Results

Unidimensional identity

The need importance means (SD) were: most important need, 6.19 (0.68); second most important need, 5.58 (0.76); least important need, 4.86 (0.85).Footnote 3 Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness positively correlated with self-determined motivation and self-esteem and negatively correlated with depression (see Table 4). Satisfaction of the most and second most important basic needs positively correlated with self-esteem and self-determined motivation and negatively correlated with depression. Satisfaction of the least important need positively correlated with self-determined motivation, but not with self-esteem, and negatively correlated with depression.

Unidimensional identity – motivated behavior

Nomothetic need importance

Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness significantly predicted self-determined motivation: autonomy; R2 = 0.46, p < 0.001; b = 17.34, p < 0.001; CI [13.24, 21.40]; competence; R2 = 0.21, p < 0.001; b = 7.34, p < 0.005; CI [2.18, 12.53]; relatedness; R2 = 0.21, p < 0.001; b = 9.90, p < 0.001; CI [4.84, 14.93]. There was a significant interaction between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy on self-determined motivation, b = 3.36; p < 0.05; CI [0.58, 6.17]. When importance of autonomy was high, satisfaction of autonomy more strongly predicted self-determined motivation than when importance was low. There were no significant interactions between satisfaction and importance of competence or relatedness on self-determined motivation.

Idiographic need importance

110 (70%) of the 158 participants reported within-person differences in the importance of all three basic psychological needs. Satisfaction of the most and second most important needs significantly predicted self-determined motivation, R2 = 0.40 p < 0.001; bs = 9.86 and 6.19; ps < 0.001 and 0.005; CIs [5.42, 14.23] and [1.89, 10.41], respectively; satisfaction of the least important need did not, b = 3.10, CI [-1.55, 7.73].

Unidimensional identity – well-being

Nomothetic need importance analysis

Need satisfaction predicted well-being: autonomy, R2 = 0.31, p < 0.001; b = 2.17, p < 0.001; CI [1.25, 3.13]; competence, R2 = 0.17, p < 0.001; b = 1.61, p < 0.005; CI [0.55, 2.68]; relatedness, R2 = 0.11, p < 0.001; b = 1.08 p < 0.05; CI [0.03, 2.10]. There was a significant interaction between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy on well-being, b = 0.93, p < 0.005, CI [0.30, 1.59]. When importance of autonomy was high, satisfaction of autonomy more strongly predicted self-determined motivation than when importance was low. There were no significant interactions between the satisfaction and importance of competence and relatedness on well-being.

Idiographic need importance analysis

Satisfaction of the most and second most important needs significantly predicted well-being, R2 = 0.24, p < 0.001; bs = 1.22 and 1.07; ps < 0.05; CIs = [0.32, 2.18] and [0.20, 1.97], respectively. Satisfaction of the least important need did not, b = 0.31; CI [-0.63, 1.25].

Multidimensional identity

The need importance means (SD) were: most important need, 6.19 (0.74); second most important need, 5.50 (0.80); least important need, 4.80 (0.91). Satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness positively correlated with self-esteem and depression (see Table 5). Satisfaction of the most, second most and least important basic needs positively related to self-esteem and depression.

Multidimensional identity – well-being

Nomothetic need importance

Need satisfaction predicted well-being: autonomy, R2 = 0.35, p < 0.001; b = 3.08, p < 0.001; CI [2.35, 3.81]; competence, R2 = 0.58, p < 0.001; b = 4.33, p < 0.001; CI [3.74, 4.92]; relatedness, R2 = 0.35, p < 0.001; b = 3.52, p < 0.001; CI [2.73, 4.31]. There were no significant interactions between the satisfaction and importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness on well-being.

Idiographic need importance

210 (73%) of the 289 participants reported within-person importance differences across the three needs. Satisfaction of the most, second most, and least important needs each significantly predicted well-being: R2 = 0.58, p < 0.001; bs = 1.00, 1.64, and 2.32; ps < 0.01, < 0.001, and < 0.001; CIs = [0.16, 1.81], [0.90, 2.40] and [1.65, 3.00], respectively.

Discussion

Analyzing the unidimensional identity data with the nomothetic analytical procedure revealed that importance did not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction and self-determined motivation (notwithstanding the likely artifactual autonomy interaction), or general well-being, further supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2 and largely consistent with Studies 1–3 and Chen et al. (2015). Analyzing the unidimensional identity data with the idiographic analytical procedure again demonstrated a need importance effect. Specifically, satisfaction of the most important and second most important needs significantly predicted self-determined motivation and general well-being, and satisfaction of the least important need did not, further supporting Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Analyzing the multidimensional identity data with the nomothetic analytical procedure showed that importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness did not moderate the relationship between need satisfaction and psychological well-being (i.e., self-esteem and depression), which is consistent with Study 3 and Chen et al. (2015) and supports Hypothesis 5. Analyzing the multidimensional identity data using the intra-individual difference analytical approach again supported Hypothesis 6. That is, for individuals with a multidimensional identity, satisfaction of more and less important needs predicted general well-being regardless of intra-individual differences in need importance.

The motivated behavior findings from participants with a unidimensional identity replicated the findings from Studies 1 and 2 and provide further support for the Intra-individual Hypothesis for self-determined motivation. Furthermore, the Intra-individual Hypothesis held for general well-being for people with a unidimensional identity. That is, for those individuals, satisfaction of the most important needs significantly predicted general well-being, but the least important needs did not. For participants with a multidimensional identity, satisfaction of all three needs had similar links with well-being, regardless of need importance.

The most important finding of Study 4 is that for individuals with a unidimensional identity, the links between basic need satisfaction and general well-being were not universal but were dependent on the importance attached to the fulfilment of a specific need. Furthermore, these findings indicate the Intra-individual Hypothesis is robust across multiple roles and activities (e.g., sport, career, parenting).

General discussion

In self-determination theory, basic psychological needs are universally fundamental for all human beings (Deci & Ryan, 2000). That is, the psychological needs that underpin motivation are the same for all humans. Other personality researchers have emphasized the importance of individual differences in need importance on the relationship between need satisfaction and outcomes (e.g., Hofer & Busch, 2011; Schüler et al., 2016). The purpose of the present research was to address whether individual differences in the strength of psychological needs affect the relationship between need satisfaction and psychological outcomes. Studies 1, 2, and 4 point to need importance meaningfully contributing to self-determined motivation for a particular activity. For general well-being, the importance of importance in basic psychological needs also applies to individuals who have a unidimensional sense of identity. This identity dimensionality differentiation appears to be because individuals with a unidimensional identity have no opportunity to compensate for unmet needs via engagement in other activities. For individuals with a multidimensional identity (i.e., more than one source of self-esteem), the Universal Hypothesis that underpins self-determination theory applies to need satisfaction globally. That is, in general life, where one has every opportunity to compensate for unmet needs, satisfaction of basic psychological needs has a similar relationship with well-being outcomes regardless of the relative importance attached to different needs.

The current research extends previous research on individualized need importance by offering an idiographic analysis to match an idiographic hypothesis. That is, similar to previous researchers (Chen et al., 2015; Flunger et al., 2013; Katz et al., 2010; Van Assche et al., 2018), we conceptualized need importance explicitly by asking participants to rate the importance of the satisfaction of each of the three basic psychological needs. Unlike previous researchers, however, we considered the data both nomothetically and idiographically with the overarching expectation that the data would support the Universal Hypothesis when we analyzed the importance data nomothetically (e.g., Chen et al.) and the Intra-individual Hypothesis when we analyzed the importance data idiographically. Given that the support for each hypothesis is dependent on the nomothetic vs. idiographic framework, researchers would do well to consider their data in this dual manner when framing tests of the relative merits of the universal and individual views.

Broader implications

The present studies also contribute to the body of research examining need importance/strength in the motive disposition literature (e.g., Hofer & Busch, 2011; Schüler & Kuster, 2011; Schüler et al., 2016). Specifically, that research demonstrates that individual differences in the strength of implicit motives influence the domain-specific outcomes derived from basic need satisfaction. However, Schüler and colleagues found nothing significant regarding generalized well-being. This lack of motive × need interaction is possibly due to the overly strict assessment of the Universal Hypothesis (cf. Neubauer et al., 2018). That research has also been criticized for using implicit motives as an indicator of need strength. Indeed, researchers have argued that the implicit motives in motive disposition theory are not directly comparable to the needs described in self-determination theory (Chen et al., 2015; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). They suggested that it is more appropriate to measure need strength by explicitly assessing the importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness. The current research is the first to show support for the moderating effect of need importance in an explicit operationalization that is congruent with the needs described in self-determination theory.

It is important to note that we used an explicit measure of need importance based on the criticisms mentioned above. However, Ryan and Deci (2000) argue that explicit measures are unable to examine the needs defined in self-determination theory. Clearly, this is a contradiction that self-determination theorists need to address. Furthermore, there appear to be at least two implications of this methodological paradox: 1) although some research suggests that there is conceptual overlap between implicit motives and basic needs (e.g., Schüler et al., 2013), further research is needed to investigate the congruence of the needs described in both motive disposition and need satisfaction; 2) for research to move beyond this methodological limitation, researchers would do well to develop an implicit measure of the strength of basic psychological needs within the self-determination theory framework.

Applied implications

Our work points to the importance of importance in very high achievers for whom motivation is critical. Thus, our findings could have potentially significant implications in understanding the enhancement of motivation and subsequent work productivity in high achievers. Employers concerned with performance enhancement might do well to try first to understand individuals’ general preferences for need satisfaction. For example, people who perceive competence to be their most important need might find it more beneficial to be provided with opportunities for achievement and feedback on the outcomes of their work. Furthermore, this sort of approach could help managers match individuals for the most productive teams. For example, it would do very little for team productivity to have a collection of individuals all high in the need for personal autonomy (Langfred, 2004).

When people develop a unidimensional identity, they neglect other aspects of life (Hardy et al., 2017; Lalande et al., 2017; Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). When need satisfaction is gained through a single activity, the individual may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of domain-specific need frustration (Milyavskaya et al., 2009; Sheldon & Niemiec). As such, it may be beneficial for clinical psychologists to consider cognitive reappraisal concerning the importance of multiple target life domains through which individuals can compensate for frustrated psychological needs and subsequently reduce vulnerability to negative life outcomes (Craven et al., 1991).

Limitations

Although the present set of studies points to identity dimensionality being an important moderator of the relative merits of the Universal Hypothesis and the Intra-individual Hypothesis, we made some assumptions about identity dimensionality across Studies 1–3. That is, based on previous research (e.g., Barlow et al., 2013; Woodman et al., 2010), we assumed that the competent rock climbers in Study 1 had a relatively unidimensional identity and that recreational sportspeople (Study 2) and the general public (Study 3) had a multidimensional identity. In Study 4, we explicitly addressed this limitation by specifically conceptualizing and analyzing participants’ identity dimensionality. As such, the present set of studies points to the need for more studies that specifically and explicitly explore identity dimensionality for discriminating between the relative link between the satisfaction of important needs and motivation and well-being.

In order to address scale validity and the specific context for need satisfaction, we modified and changed need satisfaction and need importance scales across the studies. It is thus important to assess the risk of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). For example, it is perhaps noteworthy that each use of the Basic Needs Satisfaction-General Scale (Gagné, 2003; Studies 3–4) yielded support for the Universal Hypothesis and no support for the Intra-individual Hypothesis. Although the relative support for each of these hypotheses was as hypothesized for a multidimensional identity, the BNS-G may present a bias toward supporting the Universal Hypothesis, which clearly warrants attention. The other scales presented no evidence of common method bias, as they each provided support for both the Universal Hypothesis and the Intra-individual Hypothesis within the same study, depending on the nomothetic or idiographic treatment of the data. As such, the most parsimonious explanation of the combined effects across the studies is that the differential support for the Universal Hypothesis and the Intra-individual Hypothesis is the nomothetic or idiographic treatment of the need importance data.

Regarding the measurement of need importance, we modified this scale across studies. These modifications were minor, however, and were geared toward robust validation. Specifically, in Study 1, following factor validation we retained a 10-item basic need importance scale. However, this validation process retained only two items for the importance of the need for competence. In Study 2, we aimed to address this limitation by using the same scale as in Study 1 and tested three more competence items. Following factor validation, we retained an 11-item need importance scale with three items measuring the need for competence (one more than in Study 1), thus addressing the limitation of the need importance scale developed and used in Study 1. In Study 4 we again used the 11-item need importance scale that we validated in Study 2. In Study 3, because of the cross-cultural component, we used the 12-item need importance scale that had previously been used in comparable cross-cultural research (Chen et al., 2015). However, we did not repeat the use of this scale in Study 4 because of the scale’s limitations regarding its sensitivity in distinguishing importance scores. The seven-point Likert scale of the need importance measure developed for the purpose of the present studies appears to offer greater sensitivity. As such, we recommend that researchers use this measure for future research.

Conclusion

The findings of the present studies offer support for the Intra-individual Hypothesis. Specifically, the motivation benefits associated with need satisfaction gained via a specific activity depend on the relative intra-individual importance of that need. Equally, when an individual’s sense of identity is highly related to investment in a specific activity, the general well-being benefits experienced from need satisfaction depend on intra-individual importance. The findings also offer support for the Universal Hypothesis of self-determination theory. Specifically, for the general population, when need satisfaction is measured across multiple life domains, each of the three basic needs benefit well-being equally regardless of individual differences in importance. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that although the satisfaction of all three needs is required to a similar extent for general well-being in some contexts, there are identity-related contexts in which only the satisfaction of more important needs is important.

Notes

We used 95% confidence intervals throughout this research.

We used the same sample for the nomothetic and idiographic analyses for each study.

Repeated Measures ANOVAs and Bonferroni follow-up tests confirmed that all need importance means were significantly different from each other across all studies.

References

Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., & Morin, A. J. (2015). Bayesian structural equation modeling with cross-loadings and residual covariances: comments on Stromeyer et al. Journal of Management, 41, 1561–1577.

Barlow, M., Woodman, T., & Hardy, L. (2013). Great expectations: different high-risk activities satisfy different motives. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 105, 458–475.

Brewer, B. W., & Cornelius, A. E. (2001). Norms and factorial invariance of the athletic identity measurement scale. Academic Athletic Journal, 15, 103–113.

Brunstein, J. C., & Schmitt, C. H. (2004). Assessing individual differences in achievement motivation with the implicit association test. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 536–555.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., der Kaap-Deeder, V., & J.… Verstuyf, J. . (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 216–236.

Craven, R. G., Marsh, H. W., & Debus, R. L. (1991). Effects of internally focused feedback and attributional feedback on enhancement of academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 17–27.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49, 182–185.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: a cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 930–942.

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12, 121–138.

Flunger, B., Pretsch, J., Schmitt, M., & Ludwig, P. (2013). The role of explicit need strength for emotions during learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 241–248.

Forest, J., & Paquet, Y. (2017). Obsessive passion: a compensatory response to unsatisfied needs. Journal of Personality, 85, 163–178.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

French, E. G., & Chadwick, I. (1956). Some characteristics in affiliation motivation. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52, 296–300.

Friedrich, R. J. (1982). In defense of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations. American Journal of Political Science, 26, 797–833.

Gagné, M. (2003). Autonomy support and need satisfaction in the motivation and well-being of gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15, 372–390.

Hardy, L., Barlow, M., Evans, L., Rees, T., Woodman, T., & Warr, C. (2017). Great British medalists: psychosocial biographies of super-elite and elite athletes from Olympic sports. Progress in Brain Research, 232, 1–119.

Hardy, L., & Leone, C. (2008). Real evidence for the failure of the Jamesian perspective or more evidence in support of it? Journal of Personality, 76, 1123–1136.

Hardy, L., & Moriarty, T. (2006). Shaping self-concept: the elusive importance effect. Journal of Personality, 74, 377–402.

Hofer, J., & Busch, H. (2011). Satisfying one’s needs for competence and relatedness consequent domain-specific well-being depends on strength of implicit motives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1147–1158.

Jaccard, J., Turrisi, R., & Wan, C. K. (1990). Interaction effects in multiple regression. Sage Publications.

Katz, I., Kaplan, A., & Gueta, G. (2010). Students’ needs, teachers’ support, and motivation for doing homework: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Experimental Education, 78, 246–267.

Kessler, R. C., Barber, C., Beck, A., Berglund, P., Cleary, P. D., McKenas, D., & Wang, P. (2003). The world health organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ). Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 45, 156–174.

Kruschke, J. K. (2013). Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142, 573–603.

Lalande, D. R., Vallerand, R. J., Lafrenière, M. A. K., Verner-Filion, J., Laurent, F.-A., Forest, J., & Paquet, Y. (2017). Obsessive passion: A compensatory response to unsatisfied needs. Journal of Personality, 85, 163–178.

Langfred, C. W. (2004). Too much of a good thing? negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 385–399.

Lindwall, M., Aşçi, F. H., Palmeira, A., Fox, K. R., & Hagger, M. S. (2011). The importance of importance in the physical self: Support for the theoretically appealing but empirically elusive model of James. Journal of Personality, 79, 303–334.

Marsh, H. W. (1995). A Jamesian model of self-investment and self-esteem: comment on Pelham (1995). Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 69, 1151–1160.

McClelland, D. C. (1965). Toward a theory of motive acquisition. American Psychologist, 20, 321–333.

Milyavskaya, M., Gringas, I., Mageau, G. A., Koesnter, R., Gagnon, H., Fang, J., & Boiché, J. (2009). Balance across contexts: Importance of balanced need satisfaction across various life domains. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1031–1045.

Neubauer, A. B., Lerche, V., & Voss, A. (2018). Interindividual differences in the intraindividual association of competence and well-being: combining experimental and intensive longitudinal designs. Journal of Perosnality, 86, 698–713.

Ng, J., Lonsdale, C., & Hodge, K. (2011). The basic needs satisfaction in sport scale (BNSSS): instrument development and initial validity evidence. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 12, 257–264.

Pelham, B. W., & Swann, W. B. (1989). From self-conceptions to self-worth: on the sources and structure of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 57, 672–680.

Pelletier, L. G., Rocchi, M. A., Vallerand, R. J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Validation of the revised sport motivation scale (SMS-II). Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 14, 329–341.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Qualtrics (2011 - 2015). Provo, UT: http://www.qualtrics.com.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Rees, T., Hardy, L., Abernethy, B., Güllich, A., Côté, J., Woodman, T., Montgomery, H., Laing, S., & Warr, C. (2016). The great British medalists project: a review of current knowledge into the development of the world’s best talent. Sports Medicine, 46, 1041–1058.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships: As developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed), Psychology: A study of a science. Formulations of the person and the social context (Vol. 3, pp.184–256). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan, Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Schüler, J., & Brandstätter, V. (2013). How basic need satisfaction and dispositional motives interact in predicting flow experience in sport. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, 687–705.

Schüler, J., Brandstätter, V., & Sheldon, K. M. (2013). Do implicit motives and basic psychological needs interact to predict well-being and flow?: Testing a universal hypothesis and a matching hypothesis. Motivation & Emotion, 37, 480–495.

Schüler, J., & Kuster, M. (2011). Binge eating as a consequence of unfulfilled basic needs: the moderating role of implicit achievement motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 35, 89–97.

Schüler, J., Sheldon, K. M., & Fröhlich, S. (2010). Implicit need for achievement moderates the relationship between competence need satisfaction and subsequent motivation. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 1–12.

Schüler, J., Sheldon, K. M., Prentice, M., & Halusic, M. (2016). Do some people need autonomy more than others? Implicit dispositions toward autonomy moderate the effects of felt autonomy on well-being. Journal of Personality, 84, 5–20.

Sheldon, K. M., & Gunz, A. (2009). Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. Journal of Personality, 77, 1467–1492.

Sheldon, K. M., & Niemiec, C. P. (2006). It’s not just the amount that counts: balanced need satisfaction also affects well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 91, 331–341.

Sheldon, K. M., & Schüler, J. (2011). Wanting, having, and needing: integrating motive disposition theory and self-determination theory. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 101, 1106–1123.

Sheldon, K. M., & Schüler, J. (2019). Needs, motives, and personality development: Unanswered questions and exciting potentials. In D. P. McAdams, R. L. Shiner, & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Handbook of Personality Development (pp. 276–294). Guilford Press.