Abstract

In order to be considered a basic psychological need, a candidate need should fulfill several criteria, including need satisfaction having a unique positive effect on well-being, and need frustration having a unique effect on ill-being, properties demonstrated by autonomy, competence and relatedness. Previous research has demonstrated that beneficence satisfaction—the sense of having a positive impact on other people—can have a unique positive effect on well-being. In the present study, we examined whether beneficence frustration—the sense of having a negative impact on other people—would be uniquely connected to ill-being. In the first study (N = 332; Mage = 38) we developed a scale to assess beneficence frustration. Then, in two subsequent cross-sectional studies (N = 444 and N = 426; Mage = 38/36) beneficence frustration is correlated with indicators of ill-being (negative affect, depression, anxiety, physical symptoms), but this connection disappears when controlling for the effects of autonomy, competence and relatedness need frustrations. The three needs fully mediate relations between beneficence frustration and all assessed well-being and ill-being indicators in both studies. This leads us to suggest a distinction between basic psychological needs and basic wellness enhancers, the satisfaction of which may improve well-being, but the neglect or frustration of which might not uniquely impact ill-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Basic Psychological Need Theory (BPNT), one of the six mini-theories within Self-Determination Theory, currently recognizes three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Yet, there has always been an openness to explore whether there could be other essential nutrients of psychological wellness. While various candidates have been suggested but found wanting (see Ryan and Deci 2017), one candidate showing some initial promise is beneficence, defined as the sense of having a positive impact in the lives of other people (Martela and Ryan 2016b). Beneficence is thus about the person feeling that one’s actions are having some form of prosocial impact; in some way or another making the world and the lives of other people better. This general definition means that many types of prosocial behavior ranging from donations to charity to empathic response to a person on the street to taking care of your loved ones could potentially increase a person’s experience of beneficence.

A growing body of experimental work has demonstrated how even anonymous forms of good deeds to other people can increase both the sense of beneficence (Martela and Ryan 2016a) and the well-being of the giver (Dunn et al. 2008; Whillans et al. 2016) and such results have been replicated across the world from Canada and South Africa (Aknin et al. 2013) to a small-scale rural society on the Pacific island of Vanuatu (Aknin et al. 2015). This has led to the suggestion that the emotional benefits derived from engaging in prosocial behaviour could be a “psychological universal” (Aknin et al. 2013), and to the suggestion that increased sense of beneficence could be what explains the connection between prosocial behavior and well-being (Martela and Ryan 2016a). While some work suggests that these wellness enhancing effects of prosocial behaviour are mediated by satisfaction of the three psychological needs (Weinstein and Ryan 2010), it is also possible to suggest that the “warm glow of giving” (Andreoni 1990), the simple feeling of having made a positive contribution to others, could be a direct source of human wellness, over and above the effect of the three psychological needs (Martela and Ryan 2016b).

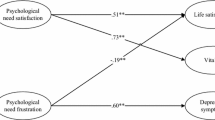

To test the hypothesis about the unique connection between beneficence and well-being, Martela and Ryan (2016b) showed in three studies that beneficence satisfaction was an independent and significant predictor of well-being even when controlling for the effects of the three basic psychological needs both on a between-person level and on a within-person level in a 10-day diary study. These results showing that beneficence has an independent relation to well-being over and above the effect of the three basic psychological need satisfactions led Martela and Ryan (2016b, p. 761) to conclude that “it is thus fair to say that beneficence as a candidate need has passed one crucial test for a potential psychological need.” However, they noted that it would be premature to draw any stronger conclusions based on this finding, as establishing whether something is or isn’t a psychological need would require a more extensive line of evidence. In particular, Ryan and Deci (2017, p. 251) note that studies on beneficence as a candidate need “thus far have not shown that deprivation of benevolence opportunities hurts (rather than simply fails to enhance) wellness.”

Research on basic psychological needs has distinguished between need satisfaction and need frustration, the latter being an active thwarting of a need rather than mere lack of satisfaction (Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013; Ryan and Deci 2017). Research has shown that while need satisfaction is more strongly related to wellness indicators, need frustration is typically related to illness indicators, with each need contributing independently to such ill-being (Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013; Bartholomew et al. 2011; Cordeiro et al. 2016). Based on this distinction, we sought to examine the role of beneficence frustration, defined as the feeling that one’s behaviors and actions have caused harm to others. Such harm to others could be caused by various behaviors, intentional and unintentional, the crucial factor being that the person in question feels that such other-harming impact has taken place. Accordingly, the two main aims of the present contribution are to first develop a measure of beneficence frustration and examine its discriminant, construct, and predictive validity, and, second, to examine beneficence frustration along with the frustrations of autonomy, competence, and relatedness to see whether it has a unique effect on ill-being even when controlling for the effects of the three basic needs.

Criteria for a basic psychological need

Research on basic needs should be conservative in the sense of employing stringent criteria for what can be considered a basic psychological need. Otherwise there is a danger of the list expanding until it no longer has much explanatory power (Deci and Ryan 2000). Accordingly, SDT has proposed a few key criteria that a candidate need has to fulfill in order to be considered a basic psychological need (see especially Ryan and Deci 2017; Martela and Ryan 2016b).

First and foremost, the satisfaction of a candidate need must be “strongly positively associated with psychological integrity, health, and well-being”, over and above the variance accounted for by the existing three needs (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 251). This criterion goes to the heart of the definition of basic psychological needs as “nutrients that are essential for growth, integrity, and well-being” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 10). Accordingly, one should expect to see a clear and non-trivial connection between need satisfaction and various indicators of wellness. This indeed is the case with the three established needs as a wide body of research has shown (see Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2017).

Second, frustration of the candidate need must be associated with negative effects on wellness and impoverished functioning. Once again, this connection should be visible over and above the variance accounted for by the existing needs (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 251). Given the fact that basic needs are supposed to be needs, the frustration of such need should lead to observable decrements in growth, integrity, and wellness. The individual who experiences chronic need frustration or neglect should display “motivational, cognitive, affective, and other psychological decrements of a specifiable nature, such as lowered vitality, loss of volition, greater fragmentation, and diminished well-being” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 86). In addition to contributing to ill-being, need frustration can lead to various types of compensatory behaviours such as oppositional defiance, rigid behavioural patterns, and loss of self-control (Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013). Research has shown that need frustration is connected to various indicators of ill-being such as depression, negative affect and burnout (e.g., Bartholomew et al. 2011), with each need frustration being uniquely connected to indicators of ill-being such as stress (Campbell et al. 2017) and depressive symptoms (Chen, Vansteenkiste et al. 2015; see also Cordeiro et al. 2016).

Any candidate need “must minimally meet these two criteria” listed above—satisfaction showing enhancement effects and frustration showing negative effects on wellness—but there are other important criteria as well (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 81). Third, a need must be essential to explain or interpret a broad variety of empirical phenomena. As a functional concept with objective criteria, a need should have explanatory power in various contexts and situations. For example, the current three basic needs have all been shown to mediate various empirical relations, such as between supportive work environments and important work outcomes (e.g. Gillet et al. 2012) or supportive learning environments and learning outcomes (e.g. Jang et al. 2009). A candidate need should similarly serve as a significant and consistent additional mediator of such relations. Fourth, a need must specify content in the sense of identifying the specific psychosocial experiences and behaviours that will lead to well-being (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 251). A need should refer to something specific about the relation of the organism to its environment, such as that the organism has room for volition or is able to connect with other people. Concepts such as well-being, vitality or meaningfulness do not specify such content, and accordingly might be better seen as outcomes of need satisfaction rather than needs. In other words, a need must be in the “appropriate category of variables” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 252), a predictor of wellness rather than an indicator of wellness as such.

Fifth, a need must be consistent with the idea of a growth need rather than a deficit need. The key distinguishing feature between these two is that growth needs “facilitate healthy development and are active on an ongoing basis” whereas deficit needs “operate only when the organism has been threatened or thwarted” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 251). Biological needs such as thirst are deficit needs that operate when the organism is lacking something. Some psychological processes such as the need for safety and security appear to operate similarly, as they are important when absent or threatened, but their connection with wellness outcomes might diminish beyond a certain point (see Chen, Van Assche, et al. 2015). Basic needs, in contrast, should not require deficiencies to motivate action. Accordingly, deficit needs should be more strongly related to aspects of ill-being than aspects of wellness or flourishing.

Sixth, a need should operate universally—for people across the lifespan and in all cultures (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 252). Basic needs are seen to be a fundamental part of human nature, and thus should be operative no matter the cultural context and “irrespective of whether they are valued by the individuals or their cultures” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 10). Thus, it is not enough to study a candidate need within one particular culture, but cross-cultural evidence of its importance around the world is also needed, as has been done with the three basic needs (e.g. Chen, Vansteenkiste et al. 2015; Chirkov et al. 2003).

The case for a candidate need would be further strengthened if a credible evolutionary story concerning the adaptive benefits of the development of such a need could be offered, if it could be shown that the individual’s motivation to satisfy the need would not substantially moderate the well-being effects, and if it would be shown that individuals gravitate toward domains and activities where the need could potentially be fulfilled. All of these considerations bear on the determination of whether something is a basic need or merely an individual or culturally specific preference.

The case for beneficence as a candidate need

Given these requirements for a basic psychological need, we can make a more informed judgment about how well beneficence as a candidate need is able to fulfill these criteria. As noted in the introduction, the first criteria about consistent relations to well-being has already received some research attention. A broad variety of experimental studies have consistently linked prosocial behaviour to increased sense of beneficence (Martela and Ryan 2016a) and to increased well-being (reviewed in, e.g. Dunn et al. 2014; Helliwell et al. 2018). While some studies seem to show that the three basic needs can fully mediate the relationship between prosocial behaviour and well-being (Martela and Ryan 2016a; Weinstein and Ryan 2010),Footnote 1 the three studies by Martela and Ryan (2016b) demonstrated that a sense of beneficence can have an independent relation to well-being, even when controlling for the contribution of the three psychological needs. The independent relation between beneficence and well-being was demonstrated on a between-person level in a study of how people perceive life in general (study 1), and in a study of situational well-being during “the single happiest event” from the last two weeks (study 2), and on a within-person level in a third study using a 10-day diary design examining daily fluctuations in need satisfaction and well-being. Another set of three studies examined the relation between beneficence, the three needs and meaningfulness in general, in a specific situation, and on a day-to-day basis (Martela et al. 2016). The results showed that in all three studies beneficence and the three needs all had independent relations to meaningfulness, even when controlling for the contribution of each other. Yet another study examined the predictive power of the three needs and beneficence with regard to meaningful work, demonstrating that beneficence was able to explain variance in meaningful work even when controlling for the three needs (Martela and Riekki 2018). Thus, although further replications would strengthen the case, it seems that beneficence is uniquely connected to various indicators of well-being, including positive affect, subjective well-being, vitality, meaning in life, and meaningful work.

The second criterion, namely that need frustration leads to ill-being controlling for other basic needs, has not to date been systematically examined and will be the target of the present study. Accordingly, we will discuss this at length below. The third criterion, the ability to explain and mediate various empirical relationships, has also not received much research attention. The study by Martela and Riekki (2018) examined how well the three needs and beneficence mediate the relations between occupational position and meaningful work showing that the mediation seemed mainly to take place through autonomy.

The fourth and fifth criteria—the candidate need having to specify content and behaving like a growth need rather than deficit need—are about the nature of the construct under scrutiny. Instead of being a general well-being outcome, beneficence involves specific content: It tells something specific about the person’s relation to its environment (in this case, that one’s impact on it is positive/negative), rather than itself being an indicator of wellness such as vitality or sense of meaning. Furthermore, beneficence seems to fall more within the growth need rather than deficit need category. Human willingness to help and benefit other people is not only visible in situations where people perceive such impact lacking. Even people who already arguably have a significant positive impact on others are often motivated to do good things to other people. For example, doing voluntary work and charitable giving tend to correlate positively (e.g. Gittell and Tebaldi 2006; Hill 2012), thus showing that having one type of prosocial impact doesn’t lead one to scale down other types of prosocial impacts.

The sixth criterion is about the cultural and developmental universality of the need. As regards the link between prosocial behaviour and well-being, cross-cultural research has indeed shown that the relationship seems to hold, no matter whether we conduct the same experiments in Canada, South Africa (Aknin et al. 2013) or a small-scale rural society on the Pacific island of Vanuatu (Aknin et al. 2015). Other research (reviewed in Aknin et al. 2013; Feygina and Henry 2015) has shown similar results in countries such as Israel (Yinon and Landau 1987) and South Korea (Nelson et al. 2015). Also the developmental universality has received some attention: 22-month-old infants already display more happiness when giving treats than when receiving treats themselves (Aknin et al. 2012) and this result has been replicated in a sample of 2- to 5-year-old children (Aknin et al. 2015). However, as regards developmental or cross-cultural work that would examine beneficence alongside the three basic psychological needs, the only study we are aware of is the one by Martela and Riekki (2018), which demonstrated that the connection of beneficence to meaningful work is similar in the US, Finland, and India, even when controlling for the three psychological needs. Thus more cross-cultural work is needed.

Finally, there are clear arguments for the adaptive benefits of being motivated to engage in prosocial behavior (see e.g. Barclay and van Vugt 2015; Gintis et al. 2003), supplying a potential evolutionary account of why it could be adaptive for feelings of beneficence to be connected to well-being. For example, engaging in prosocial deeds improves one’s reputation, which tends to increase the chance that others provide help in times of need (Nowak and Sigmund 2005). Accordingly, Ryan and Hawley (2017) argued that human benevolence would have adaptive benefits at the level of individual fitness, as well as potentially at the level of group selection, the latter being a more controversial concept within evolutionary theory.

The present studies

Given the above review of the status of beneficence as a candidate basic psychological need, the most crucial question at the present moment is to examine whether or not the frustration of beneficence leads to ill-being. The satisfaction-wellness connection has been already examined, but along with it, the frustration–languishing connection is the other key criterion that any candidate “must minimally meet” to be considered a need (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 81).

A number of previous studies have shown that hurting others undermines the well-being of the perpetrator. For example, a few studies have used the Milgram (1963) obedience paradigm in immersive virtual or video environments to show that giving electric shocks to an imagined victim leads to increased anxiety (Dambrun and Vatiné 2010) and more somatic symptoms (Slater et al. 2006). Also ostracizing someone has been shown to be painful not only for the rejected person, but also for the ostracizer (Legate et al. 2013). Based on these studies it could be argued that there is something inherently harmful about feeling that one is hurting others.

On the other hand, one could also argue that the negative connection between hurting others and well-being could be due to the fact that hurting others negatively influences the perpetrator’s sense of relatedness to others. But although hurting one’s friend often hurts also one’s relationship with that friend, these two frustrations are conceptually separate, one being about feelings of loneliness and being excluded, the other being about feeling that one is causing harm to others. Many times hurting others can also be an unintentional side effect of us being incompetent or failing at some task (e.g. ruining our co-workers project by failing to deliver our own contribution in time or dropping our friends phone to the ground so it breaks) and thus experiencing simultaneously frustration of competence and frustration of beneficence. Other times we hurt others against our will because we are forced to do it, and the frustrated autonomy might explain the negative impact on well-being. For example, Legate et al. (2013) found that the negative effects of ostracizing others in a laboratory setting were largely mediated by the frustration of autonomy and relatedness needs. Indeed, SDT postulates that harming others is rarely experienced as autonomous, and is typically basic need frustrating by being accidental or something one was forced to do (see Legate et al. 2019; Ryan and Deci 2017, Chapter 24). Accordingly, it could be argued that the frustration of the three basic psychological needs might explain any connection between beneficence frustration and well-being and ill-being indictors.

The present study thus aims to first develop and examine the validity of a scale to measure beneficence frustration and then use it to investigate two contrasting hypotheses:

-

1.

Beneficence frustration has a unique relation to ill-being, even when controlling for the effects of autonomy, competence, and relatedness frustrations. The three needs can partially mediate this relation, but should not mediate it fully.

-

2.

The relation between beneficence frustration and ill-being is fully mediated by the frustration of the three psychological needs.

These hypotheses will be examined in three studies. The first develops a scale of beneficence frustration to be used in the two subsequent studies and starts the examination of the validity of the measure. The second examines the divergent validity of the beneficence frustration scale and its connection to general sense of ill-being and whether the three need frustrations mediate this relation. The third study replicates the findings from the second study, whilst asking participant to think about how they felt during a singular particularly unhappy event.

Study 1: developing a scale to assess beneficence frustration

The aim of this study was to validate a brief but psychometrically sound measure of beneficence frustration that would be complementary to the previously developed beneficence satisfaction scale (Martela and Ryan 2016b), and general enough to be applicable across varied other-harming behaviours and interpersonal contexts. First, to assess discriminant validity, following previous research on the distinction between need satisfaction and need frustration (e.g. Chen, Vansteenkiste et al. 2015), we examined whether beneficence satisfaction and frustration items would separate in a factor analysis. Second, to assess the construct validity, we expected beneficence frustration to correlate negatively with beneficence satisfaction, self-reported prosocial behaviour, and two known predictors of prosocial behaviour, that is, empathic concern (Davis 1983) and agreeableness (John and Srivastava 1999). We also measured negative affect and search for meaning, predicting that they would each be positively correlated with beneficence frustration. The search for meaning construct was relevant because when people feel that their impact on others is hurtful or negative, this should lead to more searching for meaning given the associations of this variable with, for example, anxiety, and self-alienation (e.g., Lopez et al. 2015). In addition, a number of well-being indicators (i.e., positive affect, vitality, life satisfaction, self-esteem, presence of meaning) were included, with the expectation that these would be negatively correlated to beneficence frustration. Finally, to assess predictive validity, we examined beneficence frustration and beneficence satisfaction as simultaneous predictors of various well-being and ill-being constructs to see whether beneficence frustration has any predictive validity beyond the effect of beneficence satisfaction.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mason and Suri 2012). Of the 374 U.S. participants who answered the survey, 42 were omitted based on too fast (< 5 min) a response time or too low a score on an inattention scale (Maniaci and Rogge 2014), leaving a final sample of 332 (88.8%). Mean age was 38 (range 18 to 76) and 62% were women. Most identified as Caucasian (73%), with the rest identifying as Asian (10%), Hispanic (7%), African American (7%), Native American (0.3%), and 3% preferring not to say. The participants were asked to think about their life in general, when answering the questions, instead of providing them with a specific time frame.

Measures

Well-being

To assess positive affect, we used the 10 items (e.g. “interested,” “enthusiastic”) from Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, and Tellegen 1988) rated on a scale from 1 (very slightly) to 5 (extremely), α = .91. Life satisfaction was assessed with the five items (e.g. I am satisfied with my life) from Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985), using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), α = .93. Vitality was assessed with five items (e.g. “I feel alive and vital.”) from the Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS; Ryan and Frederick 1997). This scale had been widely used (see Martela et al. 2016) and recent research (e.g., Kawabata et al. 2017) supports the use of the 5-item version of SVS employed in the current study. It was rated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .87. Self-esteem was measured with Rosenberg’s (1965) 10 item scale (e.g., I take a positive attitude toward myself) rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), α = .93. Meaning in life was measured with the five items (e.g. “My life has a clear sense of purpose.”) of Presence of Meaning sub-scale from MLQ (Steger et al. 2006) evaluated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .92.

Ill-being

Negative affect was assessed with 10 items (e.g., “nervous,” “upset”) from the PANAS scale (Watson et al. 1988) using a scale from 1 (very slightly) to 5 (extremely), α = .92. Search for meaning was assessed with the Search for Meaning sub-scale from MLQ (Steger et al. 2006) also including five items (e.g. I am searching for meaning in my life) evaluated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .93.

Beneficence satisfaction

Beneficence satisfaction was measured with the four items (e.g., I feel that my actions have a positive impact on the people around me) from the Beneficence Scale (Martela and Ryan 2016b) rated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .83.

Prosocial behaviour

Self-reported prosocial behaviour was assessed with a six-item (e.g. I have given money to charity) scale (Pavey et al. 2012; Rushton et al. 1981). The participants were asked to rate the extent to which they had carried out these behaviours in the previous 2 weeks on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), α = .91.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness was assessed with the nine items (e.g. Is helpful and unselfish with others) of the agreeableness scale from the Big-Five inventory (John and Srivastava 1999) evaluated on a scale from 1 (Disagree strongly) to 6 (Agree strongly), α = .83.

Empathic concern

Empathic concern was measured with the 7 item (e.g. ‘I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me’) empathic concern subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis 1983) using a scale from 1 (does not describe me well) to 5 (describes me very well), α = .87.

Results

Beneficence frustration item selection and reliability

Based on the construct definition and prior literature, a pool of eight face valid items were generated to assess thwarting of beneficence. The items didn’t ask about harmful or malevolent behaviour as such, but rather the general subjective feeling of having had a negative impact on other people. All items were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). Of the 8 items, one was eliminated due to kurtosis value exceeding 1.5. For the remaining items, all skewness and kurtosis values were below 1.1, and all standard deviations exceeded 1.0, indicating adequate variability. No inter-item correlation exceeded .7, indicating that the items were not redundant. Of the remaining 7 items, the three with the lowest item-total correlations were eliminated for a final scale of 4 items, with reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of .844. We examined for gender or age differences using regression analysis, and found that gender was not associated with differences in beneficence frustration, and age was weakly negatively related to beneficence frustration (R2 = .042, p < .001). The final scale of 4 items is displayed in Appendix 1.

Discriminant validity

To examine the independence of beneficence frustration from beneficence satisfaction and thus its divergent validity, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with maximum likelihood extraction and oblimin rotation with the four beneficence satisfaction items and the four beneficence frustration items reverse-scored. Both the scree plot and eigenvalues (> 1) suggested a two factor solution with the second factor explaining 18.9% of additional variance for a total of 69.0% of variance explained. The results showed that all four beneficence satisfaction items loaded more strongly on one factor (primary loadings > .60) and all four beneficence frustration items loaded more strongly on the other factor (primary loadings > .69), with two beneficence satisfaction items demonstrating secondary loadings above .50 (.54 and .52 compared to their primary loadings of .83 and .83 respectively). Thus the EFA supports the separation of need satisfaction and frustration items, although with a few relatively strong secondary loadings. The correlation between these two factors was negative and moderate (− .462), as expected.

Construct validity

To assess construct validity, correlations between beneficence and other criterion-related variables were calculated. Beneficence frustration was negatively correlated (all p’s < .01) with self-reported prosocial behaviour (− .15), empathy (− .16), and agreeableness (− .45) thus demonstrating expected relations with various indicators of prosociality.

Predictive validity

To assess the predictive validity of the beneficence frustration scale, we first examined the zero-order correlations with various factors of well-being, which showed that beneficence frustration was positively correlated (all p’s < .01) with negative affect (.50) and search for meaning (.18), and negatively correlated with positive affect (− .30), vitality (− .42), life satisfaction (− .47), and self-esteem (− .71), and presence of meaning (− .55) supporting its criterion validity.

Regression analysis

Then, in separate regression analyses, we entered beneficence satisfaction and beneficence frustration as simultaneous predictors of various well-being and ill-being outcomes. The results showed that both had independent effects on vitality (satisfaction β = .547, p < .001, frustration β = − .165, p = .001), presence of meaning (satisfaction β = .485, p < .001, frustration β = − .330, p < .001), life satisfaction (satisfaction β = .396, p < .001, frustration β = − .286, p < .001), and self-esteem (satisfaction β = .338, p < .001, frustration β = − .557, p = .001), underscoring their separateness. However, as regards positive affect beneficence satisfaction was a significant predictor (β = .510, p < .001), while the effect of beneficence frustration was non-significant (β = − .061, p = .247). In contrast, as regards negative affect, beneficence frustration was a significant predictor (β = .459, p < .001), while the effect of beneficence satisfaction was non-significant (β = − .097, p = .070). An independent samples t test showed no gender differences in any of the examined variables and adding age as a control variable did not lead to substantial changes in any of the obtained results in the regression analyses.

Brief discussion

The psychometric properties of the brief beneficence frustration scale were satisfactory. As regards divergent validity, in an exploratory factor analysis beneficence satisfaction and beneficence frustration items loaded on separate factors, and the correlation between beneficence satisfaction and beneficence frustration was moderately negative, supporting the independence of these two constructs. As regards construct validity, the relations with various aspects of prosociality were as expected. As regards predictive validity, there was a surprisingly high negative correlation between benevolence frustration and self-esteem (− .713), which might be due to the fact that traditional conceptions of self-esteem concern a person’s appraisal of his or her value or worth in social contexts (Leary and Baumeister 2000), and being unable to contribute may weigh heavily on people’s sense of worth. Otherwise, the scale demonstrated predictive validity by relating as expected to various aspects of well-being.

Finally, both beneficence satisfaction and frustration independently predicted vitality, meaning in life, life satisfaction, and self-esteem in a regression analysis (satisfaction positively, frustration negatively), underscoring their separateness. As regards positive and negative affect, only beneficence frustration had a direct significant effect with negative affect (beneficence satisfaction had marginally significant effect), and only beneficence satisfaction had a direct significant effect with positive affect. This is in accordance with research on basic psychological needs (e.g. Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013) that has suggested and demonstrated that typically need satisfaction is more strongly related to well-being outcomes and need frustration with ill-being outcomes.

Study 2: general beneficence and basic need frustration

The aim of Study 2 was two-fold: First, we continued the psychometric assessment of the scale through examining its separateness from the three psychological needs and through examining its relations to both positively and negatively valenced wellness outcomes. Second, we wanted to directly test the two primary hypotheses by asking the participants to evaluate their general level of beneficence frustration, the frustration of the three basic needs, and various well-being and ill-being indicators. We expected beneficence frustration to be negatively correlated with positive affect, self-acceptance, and meaning, and positively correlated with negative affect, anxiety, depression, and physical symptoms. However, the main question was whether these relations would hold when controlling for the contribution of the three psychological needs identified within BPNT.

Method

Participants and procedure

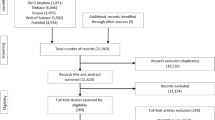

The needed sample size was estimated using G*Power 3.1 for Mac, with alpha at .05 and required power at .95. Based on previous research on the four satisfactions and well-being (Martela and Ryan 2016b) we estimated that the three needs would explain .40 of variance in various ill-being measures and beneficence would explain an additional .02 of variance. Based on these estimates, the desired sample size for multiple regression was 395. To account for possible exclusions, we recruited 452 participants from United States through Amazon Mechanical Turk. As in Study 1, we excluded participants (8 in total) who failed to answer correctly the inattention check, for a final sample size of 444. Mean age was 38 (range 19 to 77) and 56% were male. The majority were Caucasian (80%), with the rest identifying as African American (7%), Asian (6%), Hispanic (6%), American Indian (0.2%), Pacific Islander (0.2%), and 1% preferring not to say. The participants were asked to think about their life in general, when answering the questions, instead of providing them with a specific time frame.

Measures

Beneficence frustration

The frustration of beneficence was assessed with the 4 items developed in Study 1, assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all true) and 7 (very true), α = .91. The participants were asked to think how each item “relates to their life” in general.

Autonomy, competence, and relatedness frustration

The frustration of the three basic psychological needs was assessed with 4 items for each need (e.g. ‘I feel pressured to do too many things’ for autonomy, ‘I feel insecure about my abilities’ for competence, and ‘I feel excluded from the group I want to belong to’ for relatedness) from the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS; Chen, Vansteenkiste et al. 2015) rated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). The participants were asked to think how each item “relates to their life” in general. Reliabilities were as follows: autonomy, α = .91, competence, α = .95, and relatedness, α = .86.

Well-being

To assess positive and negative affect, we used the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al. 2010), comprised of 6 positive (e.g. happy, pleasant; α = .94) and 6 negative (e.g. 6 sad, unpleasant, α = .92) emotions, rated on a scale from 1 (very rarely or never) to 5 (very often or always). To assess self-acceptance, we used three items (e.g., In general, I feel confident and positive about myself) from the self-acceptance subscale of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (Ryff 1989) assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .85. Meaning in life was measured with the same five items from the MLQ (Steger et al. 2006) used in Study 1, α = .94.

Ill-being

Depression was assessed with the 10 items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) which respondents rate on a scale from 1 [rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day)] to 4 [most or all of the time (5–7 days)] how much they had felt the symptoms during the past week, α = .91. Anxiety was assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006) (e.g. ‘Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge’) assessed on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), α = .93. Physical symptoms were assessed with the 15 items (e.g. stomach pain, headaches) of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15; Kroenke et al. 2002). Participants were asked how much they have been bothered by any of the listed problems on a scale from 1 (not bothered at all) and 3 (bothered a lot), α = .86.

Results

Discriminant validity

To examine the distinctiveness of beneficence frustration items from the frustration items for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood where the four items for each of the frustration constructs loaded on separate factors, using lavaan package in RStudio 1.0. The fit indices of the model (χ2 (df = 98) = 334.979, CFI = .963, TLI = .954, RMSEA = .074, SRMR = .031) demonstrated good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999), and each of the items also loaded significantly on the intended latent factor. Moreover, the fit was superior to three alternative models where the beneficence frustration items were set to load together with autonomy (χ2 = 563.99), competence (χ2 = 920.90), and relatedness frustration items (χ2 = 532.11), respectively (Chi square difference in all three cases p < .001, the model was also superior in terms of other fit indices such as AIC, RMSEA, and CFI).

Construct validity

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of beneficence frustration, basic need frustration and well-being and ill-being indicators. As shown, beneficence frustration had positive relations with need frustrations, further supporting the construct validity of the scale.

Predictive validity

The scale had expected positive relations with all ill-being indicators and negative relations with all well-being indicators. It is also worth noting that the correlations beneficence had with the well-being and ill-being indicators were in the same range as the correlations of the three psychological needs with the same variables. The correlation between beneficence frustration and competence frustration was particularly high, .81, which is noteworthy given that the items measuring these constructs don’t have much content overlap.

Regression analysis

To examine whether beneficence frustration would have a unique effect on various well-being and ill-being indicators independently of BPNT’s three basic psychological needs, we conducted separate three-step regression analyses, in which each of the well-being and ill-being indicators was used in turn as the dependent variable (DV). In each case, in Step 1 gender and age were regressed on the DV, to control for their potential effect. In Step 2, the measures of the three need frustrations were regressed on the DV, with beneficence frustration score entered in Step 3 as a further independent factor. The results of these regression analyses are displayed in Table 2. Age and gender alone explained between .010 and .044 of variance in Step 1. As regards the three need frustrations, the results show that all three need frustrations are independently connected to depression, anxiety, and physical symptoms in Step 2. When beneficence frustration was added to the regression in Step 3, it did not demonstrate significant relations to any of the seven well-being or ill-being indicators. The only exception to these null-results was a significant positive relation to meaning in life (.20, p = .003).Footnote 2

Mediation by psychological need frustrations

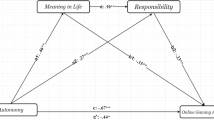

To test whether the relations between beneficence frustration and ill-being indicators would be mediated by the three psychological needs, we used PROCESS macro (version 3.3) model 4, which conducts a mediation analysis for multiple mediators using bootstrapping for indirect effects (Hayes 2018). Using each well-being and ill-being indicator in turn as the dependent variable, beneficence frustration as an independent variable, and the three needs as simultaneous mediators, we calculated the direct and indirect paths as displayed in Table 3. As seen, the direct paths became insignificant in all cases except for meaning in life, indicating full mediation through the three needs. For depression, the indirect effects through autonomy, competence, and relatedness were all significant, indicating that the mediation operated through all three. For positive affect, negative affect, anxiety, and physical symptoms, the mediation primarily operated through autonomy and competence, whereas for self-acceptance competence was the mediator. Using meaning in life as the dependent variable, the mediation was only partial, but, as noted, the relation between beneficence frustration and meaningfulness was positive rather than the negative link expected.

Brief discussion

Results indicated that our measure of beneficence frustration was distinct from those for the three need frustrations in a factor analysis, indicating discriminant validity. On a zero-order correlational level, beneficence frustration had expected and robust correlations with both basic need frustrations and all measured well-being and ill-being indicators. Yet, when the effects of the autonomy, competence and relatedness frustrations were controlled, these connections disappeared. Even though in total three well-being indicators and four ill-being indicators were examined, beneficence frustration didn’t have unique associations with any of them. Instead, mediation analyses demonstrated that the three need frustrations fully accounted for the relations between these variables. The one discrepant result was the positive and significant relation between beneficence frustration and meaning in life that appeared when controlling for need frustrations, but this appears to be a suppression effect likely due to multicollinearity, especially given the high correlation between beneficence and competence frustrations.

Study 3: situational beneficence and basic need frustration

Although in Study 2 we did not find independent effects between beneficence frustration and well-being or ill-being indicators, one could argue that this was partially due to the relatively high correlations between beneficence frustration and the frustrations of the three basic needs. As previous research has shown that the correlations between the SDT’s basic needs tend to be lower when measured with regard to specific situations instead of on a general level (e.g., Martela and Ryan 2016b), Study 3 sought to examine the relevance of beneficence frustration at the situational level. The same hypotheses as in Study 2 were addressed, yet this time asking people to think about need frustration and well-being in a specific situation. Situational in-the-moment-well-being is different from global evaluations of well-being (Schwartz et al. 2009; Wirtz et al. 2003), and especially moments of “peak affect intensity” have been shown to play an important role in wellness (Fredrickson and Kahneman 1993).

Method

Participants and procedure

For calculation of required power, we used the same estimates as in Study 2, accordingly we aimed to have at least 395 participants. To account for possible exclusions, we recruited 459 participants from United States through Amazon Mechanical Turk. As in Studies 1 and 2, we excluded participants (27 in total) who failed to answer the inattention check correctly. We also excluded 6 participants who did not write the required story. The final sample size was accordingly 426. Mean age was 36 (range 18 to 71) and 51% were male. The majority identified as Caucasian (75%), with the rest identifying as African American (8%), Asian (9%), Hispanic (5%), American Indian (1%), and 1% preferring not to say.

In the study, participants were asked to think about ‘the single unhappiest event that you experienced during the last two weeks’ and to ‘describe briefly, in a few sentences, the event that came to their mind’. After having written a brief description of the event, they were asked again to ‘think about the event and how you felt during that moment’ and answer all the scales listed below with regard to how they felt during the event.

Measures

Beneficence frustration

The frustration of beneficence was assessed with the 4 items developed in Study 1 assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all true) and 7 (very true), α = .93.

Autonomy, competence, and relatedness frustration

The frustration of the three basic psychological needs was assessed with the same 4 items for each need as in Study 2 assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all true) and 7 (very true). Reliabilities were as follows: autonomy, α = .88, competence, α = .91, and relatedness, α = .89.

Well-being

To assess situational positive and negative affect, we used the same 6 positive and 6 negative emotion items as in Study 2 (Diener et al. 2010), evaluated on a scale from 1 (very slightly) to 5 (extremely). Reliabilities were, positive affect: α = .93, negative affect: α = .77. Situational meaningfulness was measured with the two items from the subjective meaningfulness of the experience scale (King and Hicks 2009):” I felt that the event was very meaningful to me” and “The event was a very significant experience to me” rated from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .78.

Ill-being

Situational depression was assessed with 4 items (e.g. I felt that everything I did was an effort) from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) evaluated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .81. Situational anxiety was assessed with 6 items (e.g. ‘I felt nervous, anxious or on edge’) from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006) rated on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), α = .86.

Results

Discriminant validity

To assess discriminant validity, we ran a similar confirmatory factor analysis as in Study 2, with the four items for each of the frustration constructs loading on separate factors. The fit indices of the model (χ2 (df = 98) = 252.388, CFI = .970, TLI = .964, RMSEA = .061, SRMR = .036) demonstrated good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999), with each of the items loading significantly on the intended latent factor. Again, the fit was superior to three alternative models where the beneficence frustration items were set to load together with autonomy, competence, and relatedness frustration items, respectively (χ2 (df = 101) = 739, CFI < .879, TLI < .855, RMSEA > .121, SRMR > .058).

Construct validity

Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of beneficence frustration, need frustration and well-being and ill-being indicators. Beneficence frustration had still relatively high relations (.55–.67) with the three need frustrations with highest correlation again being with competence frustration.

Predictive validity

Beneficence frustration had expected positive relations with the ill-being indicators. However, the two well-being indicators—positive affect and situational meaning—provided some surprises. Positive affect had no relation to situational meaningfulness, other ill-being indicators, or to autonomy or competence frustrations. However, it was positively correlated with beneficence and relatedness frustrations. Just as surprisingly, in contrast to Study 2, situational meaningfulness was positively correlated with all ill-being indicators and all four need frustrations. We return to this in the discussion section.

Regression analysis

To examine the unique effects of beneficence frustration on various ill-being indicators independently of BPNTs basic need frustrations, we conducted a similar three-step regression analyses as in Study 2. The results of these three regression analyses are displayed in Table 5 (bottom half). Age and gender explained 2 to 4 percent of the variance in the three outcomes in Step 1. As regards the three need frustrations, the results showed that all three need frustrations were independently connected to situational depression and situational anxiety (relatedness only marginally), while for negative affect, competence was significantly, and relatedness marginally, related to it. Adding beneficence frustration to the regression in Step 3 did not provide additional predictive power with regard to any of the three ill-being outcomes, but controlling for it did strengthen some of the relations between SDT’s three basic need frustrations and ill-being outcomes. More specifically, the relations between relatedness and both negative affect and anxiety turned from marginally significant into significant, and the relation between negative affect and autonomy from non-significant to marginally significant.

Mediation by psychological need frustrations

To test whether the relations between beneficence frustration and the ill-being indicators would be mediated by the three psychological needs, we utilized PROCESS macro model 4 (Hayes 2018) as in Study 2, with beneficence frustration as the independent variable, the three needs as simultaneous mediators, and various ill-being indicators as dependent variables. The results (displayed in Table 3) indicated full mediation for all three ill-being indicators, with the mediation operating through all three needs as regards to situational depression, and through autonomy and competence as regards negative affect and situational anxiety. For the sake of comprehensiveness, we also ran mediation analyses for the two well-being indicators, even though one should interpret these with care given the unexpected positive associations between the situational meaning and three need frustrations, and between positive affect and beneficence and relatedness frustrations. There was no mediation as regards positive affect but full mediation operating through competence and relatedness as regards situational meaning.

Brief discussion

Again, beneficence frustration separated from the three need frustrations in a factor analysis and had the expected zero-order correlations with the three need frustrations and the three ill-being indicators. However, in this unhappy situation scenario, and mirroring Study 2 results, the three established needs fully mediated any relations between beneficence frustration and all three ill-being measures. The three need frustrations themselves had expected relations to all three ill-being indicators and when competing for variance in a regression analysis together with beneficence frustration, all three were significantly and independently connected to situational depression, situational anxiety, and negative affect (autonomy only marginally significantly to negative affect).

The two well-being indicators—positive affect and situational meaningfulness—showed unexpected positive relations to ill-being indicators and need frustrations. Positive affect, which was on average low for this scenario, was nonetheless associated with both relatedness and beneficence frustrations. Perhaps during particularly unhappy events people are drawn towards other people and thus could experience less loneliness and relatedness frustration. As regards situational meaningfulness, in hindsight its consistent positive relations with all need frustrations and ill-being indicators might very well be due to the fact that particularly sad and unhappy events are often perceived as meaningful events. Participants reported events like breaking up with one’s girlfriend, or a good friend’s mother dying. In such situations people probably did not experience much positive affect, but could still see the event as meaningful and significant to their lives.

General discussion

In the present article we had two key aims. First, we developed a four-item scale to measure beneficence frustration and examined its psychometric properties. The reliability of the four-item scale was satisfactory in all three studies; its discriminant validity was demonstrated by showing its separateness from beneficence satisfaction (Study 1) and the three need frustrations (Studies 2 and 3); and its construct validity was demonstrated by expected correlations such as negative relations with various indicators of prosociality, and positive relations with need frustrations. Beneficence frustration was also connected to well-being and ill-being even when controlling for beneficence satisfaction. Based on these results the psychometric properties of the scale were deemed as satisfactory.

The newly developed scale was used in Studies 2 and 3 to examine the second key aim of the article, a question central to the establishment of beneficence as a basic psychological need, namely: Would beneficence frustration have independent relations to various indicators of ill-being and well-being when controlling for the contribution of BPNT’s three basic need frustrations, or alternatively, would frustrations of autonomy, competence and relatedness fully mediate any relations of beneficence frustration with outcomes? In Study 2 we examined these questions on a general level, while in Study 3 we asked people to think about a specific, particularly unhappy, situation and indicate their attitudes and feelings during that event. The results in both studies using in total 5 well-being indicators and 7 ill-being indicators all converged on the same conclusion: Even though beneficence frustration had expected zero-order correlations with well-being and ill-being indicators, in no case was it independently connected to any well-being or ill-being indicator when controlling for the contribution of the three basic need frustrations. Instead, SDT’s three basic need frustrations fully mediated these relationships in all cases where an expected zero-order relationship existed. Accordingly, these findings suggest that the three established needs explain why the sense of having a negative impact on other people is connected to various manifestations of ill-being including negative affect, depression, anxiety and physical symptoms. Specifically, when people harm others they experience frustration of competence, autonomy, and relatedness to varying degrees.

Why did beneficence frustration fail to have a unique relation to well-being or ill-being indicators? A few different explanations could be provided. One possibility is, of course, that there was something wrong with the study design that prevented the effect to be visible. However, both studies used a methodology that has worked successfully before in detecting independent effects of beneficence need satisfaction (Martela and Ryan 2016b), and both were reasonably powered to detect even small increases in variance explained. Both studies also replicated the previous result that the three need frustrations all had independent effects on the various well-being and ill-being indicators. Thus, it is unlikely that the lack of independent effects as regards beneficence frustration were just due to methodological shortcomings. At the same time, one issue brought up in the review process was whether the two items starting with ‘I fear’ could be misinterpreted as not talking about beneficence frustration as such but a future-oriented fear, which might affect the results. To check this possibility, we recalculated the correlations and the regression analyses with a new 4 item scale not containing the ‘I fear’ items in Study 1 and with a 2-item scale not containing those items in Studies 2 and 3. Because the zero-order correlations with the needs, well-being and ill-being indicators did not change substantively (less than .10 in study 1, .03 in study 2, and .02 in study 3) and these new scales correlated highly with the original scale (.84 in Study 1, .96 in Study 2, .97 in Study 3) we tentatively conclude that the items containing the word fear, as used in this context, did not significantly influence the results.

Another possibility is that feeling that one has been anti-benevolent, or harming of others, represents a possibility that is difficult for people to integrate, as argued within SDT (Ryan and Deci 2017). Accordingly people are more likely to engage in rationalizations, self-deception, avoidance and other defenses (Simler and Hanson 2018; Weinstein et al. 2012), perhaps rendering self-evaluations of beneficence frustration less reliable than self-evaluations of, for example, autonomy, competence, or relatedness frustrations. It would be worthwhile to examine in future research whether beneficence frustration, operationalized not as “actively harming others” but rather as “having one’s chance to help thwarted” might yield different results, with the later allowing an external attribution. Similarly, the present items used to examine beneficence frustration did not state whether the harm caused to others was intentional or unintentional. Because causing harm intentionally or unintentionally may differently relate to ill-being, future research may explicitly distinguish between both types of beneficence frustration. Incidental harm, because it does not entail personal causation (de Charms 1968), might be less thwarting of basic needs like autonomy, and thus yield different results.

Finally, the full mediation by three established basic psychological needs of the relations between beneficence frustration and ill-being could be due to the fact that beneficence frustration might not have as reliable or unique a connection to ill-being as the three basic needs have. Beneficence frustration may have its negative effects mainly through the loss of autonomy, competence or relatedness it entails (e.g., Legate et al. 2013). Beneficence frustrations may mainly occur in situations when individuals feel forced to do something they don’t want to do (leading to autonomy frustration), when they fail at something and hurt someone accidentally or due to their incompetence (leading to competence frustration). In such situations connections with others may also feel compromised (leading to relatedness frustration).

In addition to these main findings, the present study makes two additional contributions to the literature. First, as regards the three basic need frustrations, the studies provide evidence that all three of them seem to be independently connected to various forms of ill-being and lack of well-being such as general depression, general anxiety, physical symptoms (Study 2), situational depression, situational anxiety, and negative affect (Study 3). These results replicate previous research (e.g. Campbell et al. 2017; Chen, Vansteenkiste et al. 2015) and further strengthen the evidence behind these three as being genuinely basic psychological needs in line with SDT’s criteria.

Second, the positive relation of situational meaningfulness to various ill-being indicators when looking at particularly unhappy events is an interesting finding. Because this was an unpredicted result it should be treated cautiously although, in hindsight, the result seems to make sense: Even negative life events might be interpreted as meaningful and significant to one’s life. Given that several studies have demonstrated a clear link between positive affect and meaningfulness (e.g. King et al. 2006; Martela et al. 2018), this contrasting phenomena of unhappy events and meaningfulness merits being studied in its own right in future research.

Distinguishing between basic psychological needs and basic wellness enhancers

As the concerns raised above indicate, it is premature to conclude that beneficence frustration will not have any reliable relations to indicators of ill-being. If, however, future studies confirm that there indeed is no unique connection between beneficence frustration and ill-being what would that mean for the possibility of beneficence being a basic need? Given that frustration leading to harm and ill-being is one of the two criteria that any candidate need “must minimally meet” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 81) the implication is clear: Beneficence frustration may not represent a basic psychological need in the way that autonomy, competence, and relatedness do.

At the same time, if beneficence as a candidate need would fulfill all the other criteria for a psychological need—such as being universal, specifying content, explaining the well-being effects of a broad variety of factors, having a credible evolutionary story and so forth—this already would make it an important, perhaps even fundamental source of well-being. As noted, research already has shown that it is consistently connected to various well-being indicators even when the effects of the three needs have been controlled for. If future research continues to show its importance as a mediator of important empirical relations, and its independent contribution to wellness, integrity and health, we might conclude at some point that beneficence could be one of the “universal, cross-developmental propensities” (Ryan and Deci 2017, p. 82) through which wellness is reliably enhanced. If future research would confirm this then this already would merit the inclusion of beneficence as one of the fundamental sources of human wellness.

This leads us to propose that a distinction should be made between basic psychological needs and basic wellness enhancers. Basic wellness enhancers are similar to basic needs in that their satisfaction should lead to well-being. But their frustration does not have to have unique effects on negative outcomes. Basic wellness enhancers would, accordingly, be defined as universal conditions for improving human thriving, the satisfaction of which should lead to more optimal development, and greater integrity and well-being. Their presence in life should make that life richer and more flourishing. But their frustration in life might not directly make that life miserable. Thus, wellness enhancers operate mainly on the positive side of the human wellness spectrum, unlike core basic needs which impact both wellness and pathology (Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013). It should be emphasized that it is premature to make any conclusions of whether beneficence should be seen as a wellness enhancer or not because several key criteria have not yet been properly investigated. However, we make this preliminary proposal of a distinction between basic needs and wellness enhancers in order to inspire future theoretical and empirical research on the topic. Other candidate wellness enhancers might include needs for nature (e.g. Ryan et al. 2010), morality (Prentice et al. 2019), and novelty (González-Cutre et al. 2016) among others. Only through empirical research can we see whether the category of wellness enhancers makes sense, and what constructs could belong to such a category.

Limitations and future research

In interpreting the results, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, results were based on cross-sectional data and are not sufficient for making causal inferences. Furthermore, it would be important to replicate mediation results using longitudinal or experimental designs to rule out the alternative interpretation that the connection between beneficence frustration and well-being indicators could also be just spurious and disappear when more robust predictors are introduced. Second, need frustration, well-being and ill-being were measured using self-report. Especially given the potential for self-deception in evaluations about one’s negative impact on others (Simler and Hanson 2018), it would be good to think of ways to control for this effect, such as measuring implicit beneficence frustration or manipulating beneficence frustration. Third, participants were from the United States and thus the extent to which these results generalize to different cultural samples is unknown. Fourth, future research should replicate the findings using scales that would explicitly differentiate between intentional and unintentional harming of others. Furthermore, it should be noted that the present article has focused on the connection between a subjective sense of harming others and subjective feelings of ill-being. Harmful behavior towards others can also lead to various social retributions and punishments, which might negatively affect the long-term well-being of the actor, but these have not been the focus of the present article. Finally, the relation between morality, which has also been proposed as a candidate need (Prentice et al. 2019) and beneficence merits attention in the future, as many types of actions might simultaneously satisfy both, although not all benevolent acts are moral as Batson et al. (1995) showed.

Conclusion

Although prior studies have demonstrated that beneficence satisfaction has independent relations to various well-being indicators, the present studies indicate that beneficence neglect or frustration might not be independently connected to ill-being indicators, once controlling for SDT’s existing three basic needs. While there are various explanations for the results, and future research is still needed, this could be an indication that, rather than being a basic psychological need, beneficence might be better considered a basic wellness enhancer, a satisfaction of which can add to well-being but for which the active frustration does not necessarily lead to greater ill-being, once controlling for the frustration of other basic needs.

Previously SDT has distinguished deficit needs (e.g., safety) as those psychological needs that become salient when people face threat, deprivation and need thwarting. The satisfaction of deficit needs can help stave off harm and protect against ill being, but may not, by themselves, directly enhance further growth, integrity and wellness (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2017). Especially safety has sometimes been investigated as a potential deficit need (Chen, Van Assche et al. 2015; Rasskazova et al. 2016). Based on the present investigations, we tentatively propose a further distinction between basic psychological needs and basic wellness enhancers, of which benevolence may be one. There may be nutriments to thriving, the frustration of which might not necessarily or uniquely predict ill-being. Beneficence is a good initial candidate, not only based on the current evidence, but also because it represents a kind of satisfaction long associated with eudaimonia, and thus it fits in well with a growing literature on the sources of human happiness and flourishing (Ryan and Martela 2016). Such distinctions, if they are empirically sustained, may help us move beyond simpler hierarchical models of needs, and help clarify how various satisfactions and frustrations facilitate or diminish human wellness and flourishing, as well as differentially contribute to human alienation, ill being, and psychopathology.

Change history

07 February 2020

The authors would like to correct the following error in the publication of the original article: The appendix 1 was missing and will hereby be added. The appendix contains the four items for the Beneficence frustration scale to assess antisocial impact.

Notes

Weinstein and Ryan (2010) also show that sense of autonomy can moderate the effect of prosocial behavior and well-being, which could be used to undermine the idea that there is a direct connection between beneficence and well-being. However as they examine prosocial behavior and don’t measure sense of beneficence as such, it remains an open question whether the link between beneficence and well-being could be similarly moderated.

Given the high correlation between beneficence and competence frustrations, as a post hoc analysis, we decided to run the same analyses without controlling for competence frustration but only autonomy and relatedness frustrations. In this case, beneficence frustration had significant relations with positive affect, self-acceptance, negative affect, depression, anxiety, and marginally significant negative relation with meaning in life. A similar post-hoc analysis in study 3 also showed that beneficence frustration had significant independent relations with situational depression and anxiety. Thus it seems that it is especially competence frustration that accounts for the insignificant relations between beneficence frustration and wellness indicators.

References

Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Burns, J., Biswas-Diener, R., … Norton, M. I. (2013). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 635–652.

Aknin, L. B., Broesch, T., Hamlin, J. K., & Van de Vondervoort, J. W. (2015). Prosocial behavior leads to happiness in a small-scale rural society. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,144, 788–795.

Aknin, L. B., Hamlin, J. K., & Dunn, E. W. (2012). Giving leads to happiness in young children. PLoS ONE,7, e39211.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal,100, 464–477.

Barclay, P., & van Vugt, M. (2015). The evolutionary psychology of human prosociality: Adaptations, byproducts, and mistakes. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 37–60). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,37, 1459–1473.

Batson, C. D., Klein, T. R., Highberger, L., & Shaw, L. L. (1995). Immorality from empathy-induced altruism: When compassion and justice conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,68, 1042–1054.

Campbell, R., Tobback, E., Delesie, L., Vogelaers, D., Mariman, A., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2017). Basic psychological need experiences, fatigue, and sleep in individuals with unexplained chronic fatigue. Stress and Health,33, 645–655.

Chen, B., Van Assche, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2015a). Does psychological need satisfaction matter when environmental or financial safety are at risk? Journal of Happiness Studies,16, 745–766.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Deeder, J., … Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 216–236.

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., & Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,84, 97–110.

Cordeiro, P., Paixão, P., Lens, W., Lacante, M., & Sheldon, K. (2016). Factor structure and dimensionality of the balanced measure of psychological needs among Portuguese high school students. Relations to well-being and ill-being. Learning and Individual Differences,47, 51–60.

Dambrun, M., & Vatiné, E. (2010). Reopening the study of extreme social behaviors: Obedience to authority within an immersive video environment. European Journal of Social Psychology,40, 760–773.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,44, 113–126.

de Charms, R. (1968). Personal causation. New York: Academic Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry,11, 227–268.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment,49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research,97, 143–156.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science,319, 1687–1688.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2014). Prosocial spending and happiness: Using money to benefit others pays off. Current Directions in Psychological Science,23, 41–47.

Feygina, I., & Henry, P. J. (2015). Culture and prosocial behavior. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 188–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Kahneman, D. (1993). Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,65, 45.

Gillet, N., Fouquereau, E., Forest, J., Brunault, P., & Colombat, P. (2012). The impact of organizational factors on psychological needs and their relations with well-being. Journal of Business and Psychology,27, 437–450.

Gintis, H., Bowles, S., Boyd, R., & Fehr, E. (2003). Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior,24, 153–172.

Gittell, R., & Tebaldi, E. (2006). Charitable giving: Factors influencing giving in US states. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,35, 721–736.

González-Cutre, D., Sicilia, A., Sierra, A. C., Ferriz, R., & Hagger, M. S. (2016). Understanding the need for novelty from the perspective of self-determination theory. Personality and Individual Differences,102, 159–169.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Helliwell, J. F., Aknin, L. B., Shiplett, H., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2018). Social capital and prosocial behavior as sources of well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. UT: DEF Publishers, Salt Lake City.

Hill, M. (2012). The relationship between volunteering and charitable giving: Review of evidence. CGAP Working Paper, Centre for Charitable Giving and Philanthropy.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., & Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students? Journal of Educational Psychology,101, 644–661.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Kawabata, M., Yamazaki, F., Guo, D. W., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2017). Advancement of the subjective vitality scale: Examination of alternative measurement models for Japanese and Singaporeans. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports,27, 1793–1800. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12760.

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2009). Detecting and constructing meaning in life events. The Journal of Positive Psychology,4, 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902992316.

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,90, 179–196.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2002). The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine,64, 258–266.

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology,32, 1–62.

Legate, N., DeHaan, C. R., Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Hurting you hurts me too: The psychological costs of complying with ostracism. Psychological Science,24, 583–588.

Legate, N., Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Ostracism in real life: Ecologically valid evidence that perpetrators of ostracism suffer, even when they feel justified. Unpublished manuscript, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Lopez, F. G., Ramos, K., Nisenbaum, M., Thind, N., & Ortiz-Rodriguez, T. (2015). Predicting the presence and search for life meaning: Test of an attachment theory-driven model. Journal of Happiness Studies,16, 103–116.

Maniaci, M. R., & Rogge, R. D. (2014). Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. Journal of Research in Personality,48, 61–83.