Abstract

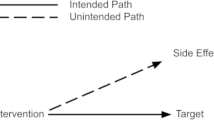

In this article, I present a philosophical account of medical treatment. In support of this account, I offer a suggestive account of medical conditions. The account of medical treatment uses three desiderata to demarcate treatment from non-treatment. Namely, a treatment should: (1) be describable by features that enable it to be standardized and characterized as a discrete intervention, (2) target a specific medical condition, and (3) have the possibility of being effective. The account of medical conditions underlies the second desideratum and attempts to tie medical conditions closely to biological dysfunction, while also including some conditions for which biological dysfunction is absent or its presence uncertain. I offer a simple typology of treatments and show how the accounts are relevant to treatment effectiveness, disease, placebos, contested treatments, and treatment standardization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

09 September 2023

Table format and titles in reference section has been corrected.

Notes

My target in this article is medical treatment, not treatment in general. For simplicity, henceforth I simply mostly refer to “treatment”.

Currently, as fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

In a work in progress, I answer this affirmatively. The implications of this — for characterizing placebos and placebo effects and establishing treatment effectiveness — are too complex to go into here, which is why I address it in another work. Nonetheless, such work is underscored by the importance that placebos-being-treatments holds for philosophical accounts of placebos. Importantly, for the present work, what have been used as placebos in clinical practice and clinical trials satisfy the “treatmenthood” desiderata I outline in the section on medical treatment desiderata.

None of which should be taken to mean that I think there is a clear-cut individuation of treatments, but rather that certain classifications are useful for certain purposes.

This approach, for example, is taken by Stegenga [13] (see also the section on pathology in the present article). This is different from requiring the possibility of effectiveness (discussed later), or something’s being effective offering presumptive evidence of treatmenthood. Knowing that a treatment is effective could be used as a meta-heuristic in cases of contested treatmenthood; i.e., something’s being effective could offer support for it being a treatment.

Which can especially be the case when safety is subsumed under effectiveness, a situation illustrated by a medical advisory board meeting I once attended where a distinguished oncologist, in full view of representatives of the pharmaceutical company that sponsored the meeting, along with a room full of other oncologists, declared the company’s drug to be poison, despite the median one month extra survival it was shown to provide in clinical studies, though at the expense of intolerable side effects. Granted, this was a view not shared by the pharmaceutical company, who believed their drug to be effective because of the improvement in survival.

Elaborating on these factors or other relevant factors and how they interact to differentiate specific treatments is beyond the scope of this article but may be a fruitful area for future research.

Although it may seem like it, this does not make treatmenthood dependent on treatment effectiveness because a poorly characterized treatment with respect to treatment effectiveness can still be a treatment.

A possibility borne out by a study conducted under the open–hidden paradigm which found the effectiveness of morphineo to be significantly higher than that of morphinec [27].

I do not draw a distinction between illicit and licit drugs with respect to whether they can be treatments (and I thus reject the legality of something as a criterion of treatmenthood). I recognize that some people might not consider use of cocaine for its psychoactive properties to have any legitimate medical purpose, even independent of cocaine’s high risk of adverse events.

I use here the terminology “medical condition” instead of “clinical condition” to avoid confusion with [32] where I list in my chart of clinical conditions what are better thought of as clinical conditions and clinical activities (such as blood donation), and which could imply that clinical conditions are characterized by their being addressed by clinicians, whereas I mean for “medical condition” to have no such necessary implication.

Medical treatment could be considered a proper subset of medical interventions, the latter of which include diagnostic interventions (such as screening programs), public health interventions (such as water fluoridation), and medical procedures/activities (such as autopsy, euthanasia, cosmetic surgery, and interventions to improve sports performance). The feature distinguishing medical treatments from public health interventions appears to be that medical treatments are directed at the individual level whereas public health interventions are directed at the population level. Either can involve changing the social context. For medical treatments, however, a description on the individual level is needed. A public health intervention could accordingly be rewritten as an individual-level medical intervention. This description might vary depending on the person (see the section “Discreteness and standardization”). For example, fluoridation of a city’s water supply is a public health intervention that operationalized as an individual-level intervention could involve for one person drinking the water whereas for another person simply showering with it. Only the former usage would constitute medical treatment for caries.

One could, by contrast, define medical conditions on the basis of what is potentially medically treatable (e.g., as Cooper [33] does with respect to defining disease). The onus then arises for defining treatment and medicine. Cooper [33, p. 278] offers the possibility of medicine being “the science practiced by doctors and other medical personnel,” and recognizes that it can be indeterminate as to what a medical treatment is.

As Stegenga [38, p. 11] wryly notes, “Not all forms of suffering are in the domain of medicine. One need only consider the suffering caused by hunger or climbing high mountains or listening to country music.”

This includes disease, environmental trauma (e.g., heatstroke, altitude sickness), injury, and poisoning.

In personal communication, Stegenga has confirmed this accurately characterizes his view. See also the earlier section on effectiveness.

As Aquino ([63], p. 7) writes “…dealing with a complaint of leg pain requires a medical understanding that can distinguish a normal response to physical exertion from a pathological condition. If the leg pain is pathological, adequate medical knowledge should enable doctors to diagnose and establish the cause, severity and complications of the condition. In cases when leg pain is not pathological, such as when it is caused by muscle fatigue after prolonged physical activity, a clinician offers reassurance and may decide that further medical investigation is not warranted. The clinical process of disease determination then involves a clinician’s use of her medical knowledge to distinguish the normal from the pathological.”

I have argued [15] that a similar problem is also encountered with the Russo–Williamson thesis. More work is needed to identify what the criteria should be that demarcate a mechanism as being “plausible.”

Especially since, for some, I do not mention the treatment target. Also, some I merely describe as nouns, whereas all treatments involve doing something, even if as simple as being administered.

Fuller [85], for example, analyzes the concept of preventive and curative medical interventions using the concept of a medical condition. However, he admits [85, p. 14] that “[a]nalyzing a concept like ‘disease’ or ‘medical condition’ is a formidable (and frequently faced) problem of its own that I will not attempt here.” He instead examines medical interventions via what he views as representative examples (and like me he views medical conditions as the more general category than diseases). Authors in the medicalization literature are also aware of the importance of this question; as Sadler et al. [86, pp. 412–413] write, “whether a human problem is, or is not, metaphysically (‘‘really’’) medical would be a question at the core of a philosophy of medicalization.”

However relevancy is determined, a matter I will not address here, other than to note that while effectiveness is typically how relevancy is determined, establishing effectiveness or its appropriate standard for any given treatment is no straightforward matter [14, 15]. Additionally, some healing traditions even determine relevancy on the basis of religious saliency. For highly specific treatments, relevancy may be a function of certain institutional features involving how the treatment is conceived and administered.

I am aware that “individualized” and “specific” have similar denotations, but for lack of better terms I use them here idiosyncratically.

References

Shapiro, A. K., and E. Shapiro. 1997. The Powerful Placebo: From Ancient Priest to Modern Physician. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Brody, H., and D. B. Waters. 1980. Diagnosis is treatment. The Journal of Family Practice 10 (3): 445–449.

Antonioli, C., and M. A. Reveley. 2005. Randomised controlled trial of animal facilitated therapy with dolphins in the treatment of depression. BMJ 331 (7527): 1231. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1231.

Steel, D., and Ş. Tekin. 2021. Can treatment for substance use disorder prescribe the same substance as that used? The case of injectable opioid agonist treatment. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 31: 271–301. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2021.0022.

Schwartz, P. H. 2017. Progress in defining disease: improved approaches and increased impact. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 42 (4): 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhx012.

Evans, D. 2002. Pain, evolution, and the placebo response. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 25 (4): 459–460. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X02260082.

Sullivan, M. D. 1993. Placebo controls and epistemic control in orthodox medicine. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 18 (2): 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/18.2.213.

Dalbosco, C. A., F. C. Filho, R. Maraschin, and L. O. Cezar. 2020. Medical discernment and dialogical praxis: treatment as healing oneself. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 23 (2): 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-020-09941-8.

Jiang, W.-Y. 2005. Therapeutic wisdom in traditional Chinese medicine: a perspective from modern science. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 26 (11): 558–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.006.

Caspi, O., and R. R. Bootzin. 2002. Evaluating how placebos produce change: logical and causal traps and understanding cognitive explanatory mechanisms. Evaluation & the Health Professions 25 (4): 436–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278702238056.

Miller, F. G., L. Colloca, and T. J. Kaptchuk. 2009. The placebo effect: illness and interpersonal healing. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 52 (4): 518–539. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0115.

Moerman, D. E. 2002. Meaning, Medicine, and the “Placebo Effect.” Cambridge University Press.

Stegenga, J. 2015. Effectiveness of medical interventions. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 54: 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2015.06.005.

Tresker, S. 2022. Treatment effectiveness, generalizability, and the explanatory/pragmatic-trial distinction. Synthese 200: 316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03517-0.

Tresker, S. 2022. Treatment effectiveness and the Russo–Williamson thesis, EBM+, and Bradford Hill’s viewpoints. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science 34 (3): 131–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698595.2022.2054396.

Doust, J., and C. Del Mar. 2004. Why do doctors use treatments that do not work? BMJ 328 (7438): 474–475. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7438.474.

Grünbaum, A. 1986. The placebo concept in medicine and psychiatry. Psychological Medicine 16 (1): 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700002506.

Holman, B. 2015. Why most sugar pills are not placebos. Philosophy of Science 82 (5): 1330–1343. https://doi.org/10.1086/683817.

Howick, J. 2017. The relativity of ‘placebos’: defending a modified version of Grünbaum’s definition. Synthese 194 (4): 1363–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-1001-0.

Friesen, P. 2020. Towards an account of the placebo effect: a critical evaluation alongside current evidence. Biology & Philosophy 35 (1): 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-019-9733-8.

Kaptchuk, T. J., and F. G. Miller. 2015. Placebo effects in medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 373 (1): 8–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1504023.

Walach, H. 2011. Placebo controls: historical, methodological and general aspects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366 (1572): 1870–1878. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0401.

Blease, C. 2018. Consensus in placebo studies: lessons from the philosophy of science. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 61 (3): 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2018.0053.

Blease, C. 2018. Psychotherapy and placebos: manifesto for conceptual clarity. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00379.

Kreek, M. J. 2000. Methadone-related opioid agonist pharmacotherapy for heroin addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 909: 186–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06683.x.

Walker, M. J. 2018. Patient-specific devices and population-level evidence: evaluating therapeutic interventions with inherent variation. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 21 (3): 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-017-9807-9.

Colloca, L., L. Lopiano, M. Lanotte, and F. Benedetti. 2004. Overt versus covert treatment for pain, anxiety, and Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet Neurology 3 (11): 679–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00908-1.

Peiris, N., M. Blasini, T. Wright, and L. Colloca. 2018. The placebo phenomenon: a narrow focus on psychological models. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 61 (3): 388–400. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2018.0051.

Branthwaite, A., and P. Cooper. 1981. Analgesic effects of branding in treatment of headaches. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 282 (6276): 1576–1578. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.282.6276.1576.

Kaptchuk, T. J., J. M. Kelley, L. A. Conboy, R. B. Davis, C. E. Kerr, E. E. Jacobson, I. Kirsch, R. N. Schyner, B. H. Nam, L. T. Nguyen, M. Park, A. L. Rivers, C. McManus, E. Kokkotou, D. A. Drossman, P. Goldman, and A. J. Lembo. 2008. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 336 (7651): 999–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dza.2010.04.011.

Kukla, Q. 2014. Medicalization, “normal function,” and the definition of health. In: The Routledge Companion to Bioethics, eds. J. D. Arras, E. Fenton, and Q. Kukla. Milton Park: Routledge Handbooks Online.

Tresker, S. 2020. Theoretical and clinical disease and the biostatistical theory. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 82: 101249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2019.101249.

Cooper, R. 2002. Disease. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 33: 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-3681(02)00018-3.

Boorse, C. 2016. Goals of medicine. In Naturalism in the Philosophy of Health. History, Philosophy and Theory of the Life Sciences, ed. É. Giroux. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29091-1_9.

Miettinen, O. S., and K. M. Flegel. 2003. Elementary concepts of medicine: V. Disease: one of the main subtypes of illness. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 9 (3): 321–323. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00418.x.

Boorse, C. 1997. A rebuttal on health. In What is Disease?, eds. J. M. Humber, and R. F. Almeder. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59259-451-1_1.

Aronowitz, R. A. 2009. The converged experience of risk and disease. The Milbank Quarterly 87: 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00563.x.

Stegenga, J. 2021. Medicalization of sexual desire. European Journal of Analytic Philosophy 17 (2): S5–34. https://doi.org/10.31820/ejap.17.3.4.

Schwartz, P. H. 2007. Defining dysfunction: natural selection, design, and drawing a line. Philosophy of Science 74 (3): 364–385. https://doi.org/10.1086/521970.

Boorse, C. 1977. Health as a theoretical concept. Philosophy of Science 44: 542–573. https://doi.org/10.1086/288768.

Boorse, C. 2014. A second rebuttal on health. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 39 (6): 683–724. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhu035.

Boorse, C. 2011. Concepts of health and disease. In: Handbook of the Philosophy of Science: Philosophy of Medicine, ed. F. Gifford, 13–64. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cresswell, M. 2008. Szasz and his interlocutors: reconsidering Thomas Szasz’s “Myth of Mental Illness” thesis. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 38: 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2008.00359.x.

Fuller, J. 2018. What are chronic diseases? Synthese 195 (7): 3197–3220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1368-1.

Tresker, S. 2020. A typology of clinical conditions. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 83: 101291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2020.101291.

Schwartz, P. H. 2008. Risk and disease. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 51 (3): 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0027.

Schramme, T. 2007. The significance of the concept of disease for justice in health care. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 28 (2): 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-007-9031-3.

Insel, T. R., and B. N. Cuthbert. 2015. Medicine. Brain disorders? Precisely. Science 348 (6234): 499–500. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2358.

White, P. D., H. Rickards, and A. Z. Zeman. 2012. Time to end the distinction between mental and neurological illnesses. BMJ 344: e3454. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e3454.

Boorse, C. 1976. What a theory of mental health should be. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 6: 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1976.tb00359.x.

Graham, G. 2013. Ordering disorder: mental disorder, brain disorder, and therapeutic intervention. In: The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry. Edited by K. W. M. Fulford, M. Davies, R. G. T. Gipps, G. Graham, J. Z. Sadler, G. Stanghellini and T. Thornton. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199579563.013.0032.

Jefferson, A. 2020. What does it take to be a brain disorder? Synthese 197: 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1784-x.

Papineau, D. 1994. Mental disorder, illness and biological disfunction. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement 37: 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135824610000998X.

Schramme, T. 2013. On the autonomy of the concept of disease in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00457.

Cosmides, L., and J. Tooby. 1999. Toward an evolutionary taxonomy of treatable conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108: 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.108.3.453.

Boorse, C. 2023. Boundaries of disease: disease and risk. Medical Research Archives 11 (4). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v11i4.3599.

Horwitz, A. V., and J. C. Wakefield. 2007. The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow into Depressive Disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Szasz, T. S. 1960. The myth of mental illness. American Psychologist 15(2): 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046535.

Moncrieff, J. 2020. It was the brain tumor that done it!”: Szasz and Wittgenstein on the importance of distinguishing disease from behavior and implications for the nature of mental disorder. Philosophy Psychiatry & Psychology 27 (2): 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2020.0017.

O’Leary, D. 2021. Medicine’s metaphysical morass: how confusion about dualism threatens public health. Synthese 199 (1–2): 1977–2005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02869-9.

O’Leary, D. 2018. Why bioethics should be concerned with medically unexplained symptoms. The American Journal of Bioethics 18 (5): 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2018.1445312.

Fainzang, S. 2013. The other side of medicalization: self-medicalization and self-medication. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry 37 (3): 488–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-013-9330-2.

Aquino, Y. S. J. 2020. Is ugliness a pathology? An ethical critique of the therapeuticalization of cosmetic surgery. Bioethics 34 (4): 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12721.

O’Leary, D. 2019. Ethical classification of ME/CFS in the United Kingdom. Bioethics 33 (6): 716–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12559.

Wakefield, J. C. 1992. The concept of mental disorder: on the boundary between biological facts and social values. American Psychologist 47 (3): 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.47.3.373.

Wakefield, J. C. 1992. Disorder as harmful dysfunction: a conceptual critique of DSM-III-R’s definition of mental disorder. Psychological Review 99 (2): 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.232.

Wakefield, J. C. 2021. Defining Mental Disorder: Jerome Wakefield and His Critics, eds. L. Faucher, and D. Forest. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9949.001.0001.

Schramme, T. 2010. Can we define mental disorder by using the criterion of mental dysfunction? Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 31 (1): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-010-9136-y.

Kingma, E. 2013. Naturalist accounts of mental disorder. In: The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry. Edited by K. W. M. Fulford, M. Davies, R. G. T. Gipps, G. Graham, J. Z. Sadler, G. Stanghellini and T. Thornton. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199579563.013.0025.

Brülde, B. 2003. The concept of mental disorder. Philosophical Communications Web Series; #29. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/handle/2077/19471/gupea_2077_19471_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 14 August 2023.

Beauvais, F. 2016. “Memory of water” without water: modeling of Benveniste’s experiments with a personalist interpretation of probability. Axiomathes 26: 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-015-9279-6.

Grimes, D. R. 2012. Proposed mechanisms for homeopathy are physically impossible. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies 17: 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7166.2012.01162.x.

Maddox, J., and J. Randi, W. Stewart. 1988. “High-dilution” experiments a delusion. Nature 334: 287–290. https://doi.org/10.1038/334287a0.

Sehon, S., and D. Stanley. 2010. Evidence and simplicity: why we should reject homeopathy. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 16: 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01384.x.

Smith, K. 2012. Against homeopathy–a utilitarian perspective. Bioethics 26: 398–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2010.01876.x.

Smith, K. 2012. Homeopathy is unscientific and unethical. Bioethics 26: 508–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01956.x.

Teixeira, J. 2007. Can water possibly have a memory? A sceptical view. Homeopathy: The Journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy 96: 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.homp.2007.05.001.

Benedetti, F. 2009. Placebo Effects: Understanding the Mechanisms in Health and Disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jopling, D. A. 2013. Placebo effects in psychiatry and psychotherapy. In: The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry. Edited by K. W. M. Fulford, M. Davies, R. G. T. Gipps, G. Graham, J. Z. Sadler, G. Stanghellini and T. Thornton. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199579563.013.0070.

Bickerdike, L., A. Booth, P. M. Wilson, K. Farley, and K. Wright. 2017. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. British Medical Journal Open 7 (4): e013384. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384.

Sholl, J. 2017. The muddle of medicalization: pathologizing or medicalizing? Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 38 (4): 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-017-9414-z.

Busfield, J. 2017. The concept of medicalisation reassessed. Sociology of Health & Illness 39 (5): 759–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12538.

Costa-Neto, E. M. 2012. Zoopharmacognosy, the self-medication behavior of animals. Interfaces Científicas – Saúde e Ambiente 1 (1): 61–72. https://doi.org/10.17564/2316-3798.2012v1n1p61-72.

Wampold, B. E. 2015. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry 14 (3): 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20238.

Fuller, J. 2022. Preventive and curative medical interventions. Synthese 200: 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03579-0.

Sadler, J. Z., F. Jotterand, S. C. Lee, and S. Inrig. 2009. Can medicalization be good? Situating medicalization within bioethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 30 (6): 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-009-9122-4.

Skivington, K., L. Matthews, and S. A. Simpson et al. 2021. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 374: n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061.

Stiles, W. B. 2009. Responsiveness as an obstacle for psychotherapy outcome research: it’s worse than you think. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 16: 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01148.x.

Fuller, J. 2013. Rationality and the generalization of randomized controlled trial evidence. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 19 (4): 644–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12021.

Stegenga, J. 2018. Medical Nihilism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Christopher Boorse, Andreas De Block, Bert Leuridan, Diane O’Leary, Jonathan Sholl, and Jacob Stegenga, plus two anonymous reviewers for this journal, for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The author was supported by the Fonds Voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Vlaanderen (FWO; Research Foundation – Flanders; 1130819N) during part of the writing of this paper and is grateful for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tresker, S. An account of medical treatment, with a preliminary account of medical conditions. Theor Med Bioeth 44, 607–633 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-023-09641-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-023-09641-3