Abstract

Building on the literature on gender role theory and brand gender, this research examines how gender-based stereotypes regarding emotional behaviors can influence consumers’ response to brand emotions. Three experimental studies demonstrate that consumers hold the same gender-based expectations of brands as they do with human emotions. In particular, they show that masculine brands can suffer from the stereotype that masculinity is typically associated with emotional control. Consumers will judge the emotional expression of a masculine brand less appropriate, which will negatively affect the perceived sincerity of the brand. Downstream negative consequences of brand masculinity include message attitude, brand attitude, and intentions to recommend the brand. Evidence of this effect is provided for emotions that are typically associated with femininity (happiness and sadness) and masculinity (anger and pride).

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The author confirms the availability of the data for all studies: https://osf.io/XPY3J/

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356.

Aggarwal, P., & McGill, A. L. (2012). When brands seem human, do humans act like brands? Automatic behavioral priming effects of brand anthropomorphism. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(2), 307–323.

Azar, S. L. (2013). Exploring brand masculine patterns: moving beyond monolithic masculinity. The Journal of Product and Brand Management, 22(7), 502–512.

Barrett, L. F., & Bliss-Moreau, E. (2009). She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day: attributional explanations for emotion stereotypes. Emotion, 9(5), 649–658.

Boerman, S. C., Reijmersdal, E. A., & Neijens, P. C. (2014). Effects of sponsorship disclosure timing on the processing of sponsored content: a study on the effectiveness of European disclosure regulations. Psychology and Marketing, 31(3), 214–224.

Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., Allison, C., & Morton, L. C. (2012). Gender differences in self-conscious emotional experience: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981.

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: a three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114(4), 864–886.

Fournier, S., & Alvarez, C. (2012). Brands as relationship partners: warmth, competence, and in-between. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2), 177–185.

Grohmann, B. (2009). Gender dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(1), 105–119.

Guevremont, A., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Consonants in brand names influence brand gender perceptions. European Journal of Marketing, 49(1/2), 101–122.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York City, NY: Guilford Publications.

Hess, U., David, S., & Hareli, S. (2016). Emotional restraint is good for men only: the influence of emotional restraint on perceptions of competence. Emotion, 16(2), 208–213.

Hutson-Comeaux, S. L., & Kelly, J. R. (2002). Gender stereotypes of emotional reactions: how we judge an emotion as valid. Sex Roles, 47(1–2), 1–10.

Jain, S. P., & Posavac, S. S. (2004). Valenced comparisons. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(1), 46–58.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 498.

Kalokerinos, E. K., Greenaway, K. H., & Casey, J. P. (2017). Context shapes social judgments of positive emotion suppression and expression. Emotion, 17(1), 169–186.

Lieven, T., Grohmann, B., Herrmann, A., Landwehr, J. R., & van Tilburg, M. (2014). The effect of brand gender on brand equity. Psychology and Marketing, 31(5), 371–385.

Lieven, T., Grohmann, B., Herrmann, A., Landwehr, J. R., & van Tilburg, M. (2015). The effect of brand design on brand gender perceptions and brand preference. European Journal of Marketing, 49(1/2), 146–169.

MacInnis, D. J., & Folkes, V. S. (2017). Humanizing brands: when brands seem to be like me, part of me, and in a relationship with me. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(3), 355–374.

Nan, X., & Heo, K. (2007). Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 63–74.

Neel, R., Becker, D. V., Neuberg, S. L., & Kenrick, D. T. (2012). Who expressed what emotion? Men grab anger, women grab happiness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(2), 583–586.

Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Desire to acquire: powerlessness and compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(2), 257–267.

Shields, S. A. (2005). The politics of emotion in everyday life: “appropriate” emotion and claims on identity. Review of General Psychology, 9(1), 3–15.

Thompson, D. V., & Malaviya, P. (2013). Consumer-generated ads: does awareness of advertising co-creation help or hurt persuasion? Journal of Marketing, 77(3), 33–47.

Thompson, C. J., Rindfleisch, A., & Arsel, Z. (2006). Emotional branding and the strategic value of the doppelgänger brand image. Journal of Marketing, 70(1), 50–64.

Ulrich, I., Tissier-Desbordes, E., & Dubois, P. L. (2011). Brand gender and its dimensions. In A. Bradshaw, C. Hackley, & P. Maclaran (Eds.), European advances in consumer research (Vol. 9, pp. 136–143). Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research.

Warner, L. R., & Shields, S. A. (2009). Judgements of others’ emotional appropriateness are multidimensional. Cognition & Emotion, 23(5), 876–888.

Waytz, A., Heafner, J., & Epley, N. (2014). The mind in the machine: anthropomorphism increases trust in an autonomous vehicle. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 113–117.

Wu, L., Klink, R. R., & Guo, J. (2013). Creating gender brand personality with brand names: the effects of phonetic symbolism. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 21(3), 319–330.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jessica Darveau (Université Laval) for her helpful suggestions and comments.

Funding

This work was supported by IÉSEG School of Management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

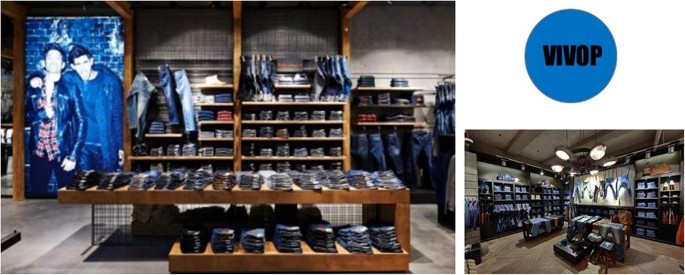

Appendix 1. Brand priming (studies 1 and 3)

-

a)

Masculine priming. Vivop is a clothing-retail company. Vivop is considered a highly adventurous brand. Its values are hard work, fearless exploration and unwavering originality.

-

b)

Feminine priming. Vivop is a clothing-retail company. Vivop is considered a highly sensitive brand. Its values are openness, proximity and enthusiasm.

Appendix 2. Study 1

-

a)

Masculine brand condition

-

b)

Feminine brand condition

Appendix 3. Study 2

Stimuli

Manipulation check

Appendix 4. Study 3

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boeuf, B. Boys do not cry: the negative effects of brand masculinity on brand emotions. Mark Lett 31, 247–264 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09519-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09519-7