Abstract

Covid-19 is an unprecedented crisis that faces the majority of governments around the world. The pandemic has resulted in substantial changes to government work cultures, financial management, and the implementation of good governance. The paper has shown how these governments react to the crisis caused by Covid-19. We analyse strategy, policy, and financial management when facing Covid-19 and give a result that will contribute to the development of crisis governance field. In this article, we argue that the most successful action in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in high income, upper-middle income, and lower-middle income countries is guided by the implementation of good governance principles. Data used in this research was obtained from the World Health Organization and the World Bank. The results indicate that countries that have been able to manage the COVID-19 pandemic have good governance indicators, such as voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

At the end of 2019, a virus known as SARSCoV2 appeared in Wuhan, China. Subsequently, the virus developed into a plague called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19), which has rapidly spread throughout various countries (Wilder-Smith et al., 2020). At the onset of COVID-19’s emergence, it was assumed to have impacts similar to previous developing viruses, namely SARS (Chan et al., 2020); yet, in reality, COVID-19 has continued to develop and cause various unforeseen problems in several countries. Accordingly, every country, in terms of both the government and the public, reacted differently in addressing the transmission of COVID-19. Viral plagues/diseases undoubtedly have differing impacts on every country, depending on the policy making strategies carried out by the respective countries (Adivar & Selen, 2013).

The policies that governments make are considered to have substantial influence in the prevention and transmission of the pandemic in each country (Adivar & Selen, 2013; Afayo et al., 2019). A country’s performance in dealing with its problems—in this case, is the Covid-19 pandemic—does indeed rely on the performance of its government (Gisselquist & Resnick, 2014). Good governance, accordingly, presents itself as a major approach for assessing governmental performance (Ahlerup & Hansson, 2011). Good governance can also function as a motivating factor for realizing the political system of an administration by prioritizing processes of policy formulation, implementation in development, and implementation of effective, efficient, and transparent public administration bureaucracy, as its common elements (Zafarullah & Huque, 2001) that can improve public welfare.

The advent of COVID-19 has certainly resulted in varying reactions from each country. There are a number of countries that have succeeded in suppressing the level of COVID-19 transmission through quick and appropriate policy responses, as demonstrated by South Korea (Choi, 2020). Nonetheless, there are also several countries that still, to this day, struggle with increasing cases, such as the United States, which has reached over 6 million cases (WHO, 2020). These differences are, without a doubt, caused by several factors. One of the main factors is government performance in facing issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic. To understand why countries perform well during a time of crisis is of significant importance for crisis response (Schomaker & Bauer, 2020). Studies about how public administration systems and good governance responses to the pandemic mainly focus on social equity and government responses to the pandemic (Deslatte et al., 2020), policy change and adaptive funding for local government on the front lines (Kettl, 2020), policy shift from surveillance and mitigation to recovery and prevention (Gupta et al., 2020), the need for loosening administrative rules for government to response pandemic (Goodman et al., 2021), the impact of collective bargaining negotiations and the public relation (Fay & Ghadimi, 2020), and the impact of government emergency public information to protective behaviour of individuals against COVID-19 (Dai et al., 2020). However, little attention has been paid to the question of how governance indicators affect the success of managing the COVID-19 pandemic and how high income, upper-middle and lower-middle countries are facing this crisis. Hence, the current study answers the call from OECD (2020), which emphasizes that in a pandemic, governance matters more than ever. Therefore, there is a need to provide a better understanding of this phenomenon. Further, this study provides evidence that governance arrangements have played a pivotal role in countries’ immediate responses and will continue to be crucial both to recovery and to the building of new, normal government activities. In addition, the study is expected to show how the discourse of governance functions, and the way the government system functions, in responding to Covid-19 (Cossin et al., 2020; Paudel, 2020; Weinberg & Grogan, 2020).

2 Literature review

2.1 Crisis governance

A crisis is defined as a threat that is thought to be existential in some sense (Boin et al., 2018; Rosenthal et al., 2001). It occurs when a group, organization, or community encounters a "serious threat to the fundamental structures or fundamental values and norms of a system, necessitating making critical decisions under time constraints and highly uncertain circumstances." (Boin et al., 2018; Rosenthal et al., 1989). In the context of crisis governance, it refers to the process by which the stakes and timeframe for change are altered, resulting in financing instability and conflicts with the organization's objective (Adebola, 2021; Boubaker & Nguyen, 2018; Janssen & Van Der Voort, 2020; McMullin & Raggo, 2020; Shadmi et al., 2020). What type of governance is most resilient in the face of a crisis? Is a decentralized approach sufficient? (Martin, 2013). These questions will always arise when routine situations devolve into insecurity. Zhang & Huang (2021) use the term crisis governance interchangeably with risk governance, referring to "the diverse ways in which numerous actors, individuals, and institutions deal with risks surrounded by uncertainty, complexity, and/or ambiguity" (Hermans et al., 2012). Military invasions, internal coups, political paralysis, widespread corruption, and revolutionary change are all possible sources of political crisis (Martin, 2013). In this context, all countries faced similar but distinct challenges in transitioning from routine to crisis governance, with varying degrees of success (and failure) in containing the virus and mitigating economic damage (Bromfield & McConnell, 2021). While all those involved demonstrated impressive improvisational abilities as the crisis unfolded, conflicts between governance levels appear unavoidable, even in times of crisis (Janssen & Van Der Voort, 2020).

The majority of sensible responses to crises are represented in central policies and decisions (Jing, 2021). Organizational instability, media pressure, stress, and erroneous information are just a few of the reasons that make making effective judgements extremely challenging for crisis leaders (Boin &’T Hart, 2003). However, it is well known that a crisis legitimizes central power, as decision-making levels must be constrained in order to make rapid decisions (Hamblin, 1958; Janssen & Van Der Voort, 2020). This is critical, as we saw friction between central and decentralized levels of authority in response to COVID-19 in a number of federalist countries (Janssen & Van Der Voort, 2020). COVID-19 is the century's second transnational mega-crisis (following the financial crisis) (Boin et al., 2010). While stability and adaptability appear to be mutually exclusive, both are necessary during times of crisis (Janssen & Van Der Voort, 2016). While adaptation necessitates change, stability must be maintained. Bureaucracies are often built for stability and efficiency, with established tasks, responsibilities, procedures, and forms. Adaptability is equally applicable to society as a whole during times of crisis (Janssen & Van Der Voort, 2020). The pandemic's continued spread and resulting instability have significantly harmed some countries' capacity to manage social risk and crisis governance. In terms of risk communication, effective dialogue between diverse stakeholders is a necessary condition for effective public crisis management. Governments must inform the public about what is occurring, what may occur in the future, and what it means to them (Boin et al., 2008). A rapid crisis response and social recovery helps to reduce losses and create a safe, social environment. Overall, public crisis governance requires numerous societal sectors, including governments, enterprises, communities, and individuals, as well as mass media involvement (Zhang & Huang, 2021b).

2.2 Good governance indicators

Many studies have been conducted to show how these indicators have positive influence in the good governance implementation (Table 1).

2.2.1 Voice and accountability

Various existing studies explain voice and accountability as two interconnected elements (O’Neil et al., 2007; Torgler et al., 2011). Voice refers to the capacity for expressing opinions and interests that are usually directed at influencing government priority or the government’s decision making process (O’Neil et al., 2007). Voice can make original claims or react to official choices. It can be peaceful or disruptive. It can happen among civil society, political parties, citizens and governmental institutions, or even within the state (Goetz & Jenkins, 2002). A strong voice can help curb politicians' misuse of power and allow voters to participate in the political process (Torgler et al., 2011).

Meanwhile, accountability is present when decision makers or lawmakers (politicians and public officials) are able to address all issues/necessities of the public whose lives depend on those rules and regulations, and when they are willing to receive sanctions for unsatisfactory performance (O’Neil et al., 2007). In other words, there are two dimensions in accountability: answerability and enforceability. The implementation of both dimensions undoubtedly requires transparency (Moore & Teskey, 2006). Accountability concerns the relationship between the holder of a right and the agents or agencies entrusted with carrying out or honoring that right (Gloppen et al., 2003). Accountability also has an accounter and an accountee, with the accounter being the agent who demands answers and sanctions (Moore & Teskey, 2006; O’Neil et al., 2007). Accordingly, voice and accountability are often understood as the public’s capacity in expressing their views/interests (participating) and the government’s capacity in accommodating those views/interests (Kock & Gaskins, 2014; Ssebunya, 2014).

Voice and accountability are among the methods employed by governments in order to be able to shape or maintain obedience by providing assurance to the public (Torgler et al., 2011). Voice and accountability provide people with access to participation in state governance (Kock & Gaskins, 2014). Some studies mention that voice and accountability are diverse and dynamic as they contain various aspects that connect the public with state actors (Ssebunya, 2014). Nonetheless, voice and accountability are considered one of the most significant dimensions in governance since they can maintain the continuity of rules within a country (O’Neil et al., 2007).

In various Latin American and Sub-Saharan African nations, for example, a prior study found a positive association between internet diffusion and government corruption (Kock & Gaskins, 2014). Furthermore, the Internet can assist in maintaining dialogue with stakeholders (Héroux & Fortin, 2013; Unerman & Bennett, 2004). Internet diffusion refers to the ease of access that a government provides to the public by encouraging economical prices and the development of supporting infrastructure (commonly observed in developing countries). The study conducted by Kock and Gaskins (2014) found that internet diffusion can, ultimately, result in easy, public access for overseeing the performance of every decision made by the government. It can also create governments that are more reactive to their constituents by providing them with updated information periodically via the internet (voice and accountability). In some countries, such easy internet access has subsequently raised the public’s critical awareness and even led to reducing the level of corruption in some Latin American and Sub-Saharan African countries (Kock & Gaskins, 2014). Conclusively, voice and accountability can indeed play a key role in a state’s system, because, in addition to maintaining the relationship between the people and public agents, voice and accountability can also mediate relations among other dimensions within governance.

2.2.2 Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism

According to a World Bank, political stability and the absence of violence/terrorism indicate how likely the government is to be destabilized or toppled through unlawful or violent tactics, such as politically motivated violence or terrorism. (Kaufmann et al., 2010). A study by Kurecic and Kokotovic (2017), for instance, discusses the relationship between FDI and political stability. FDI is considered a key driver in a country’s economic growth, particularly in developing countries. Meanwhile, direct investments given by foreign institutions/parties are frequently considered to pay attention to political stability and the absence of violence as a crucial point of consideration (Kurecic & Kokotovic, 2017).

Prior studies have discussed political stability and the absence of violence in correlation with FDI. Kim (2010) claims that FDI is increasing in nations with high levels of political corruption and instability. Khan and Akbar (2013) concluded that most political risk indicators have a negative association with FDI for the world and for high-income countries, but the biggest relationship was for upper middle-income countries. Issues of political stability and violence/terrorism do, indeed, pose frequent challenges to developing countries (middle-income countries) and have direct impacts on various aspects, including a country’s economic stability (Khan & Akbar, 2013; Kim, 2010; Kurecic & Kokotovic, 2017). Accordingly, investment assistance like FDI often pays close attention to political stability and the level of violence/terrorism that a country maintains to provide temporary assistance for the purpose of alleviating the numerous problems in said country (Khan & Akbar, 2013). In other words, a country’s political stability and absence of violence/terrorism may indicate the country’s level of capacity. If a country’s political stability is poor and the level of violence/terrorism is high, then the country’s system of governance has not been well managed. This is commonly found in developing countries. Meanwhile, if a country’s political stability is good and the level of violence/terrorism is low, then its system of governance has been managed properly (Kurecic & Kokotovic, 2017).

2.2.3 Government effectiveness

Government effectiveness functions as one of the indicators for measuring government performance by using the good governance approach (Kaufmann et al., 2010). Its purpose is to observe the capacity of each country in implementing the various decisions made by assessing the following aspects: quality of public services and employees; decision making not associated with political pressure; quality of policy; and government commitment and credibility towards a policy (Whitford & Lee, 2012). Another study also states that a high level of government effectiveness may be supported by a strong sense of nationalism maintained by policy or decision makers (Ahlerup & Hansson, 2011). The two arguments are correlated because the policy makers’ strong sense of nationalism may, indeed, help improve every element of government effectiveness such as decisions made based on state interest and solid government commitment (Ahlerup & Hansson, 2011; Whitford & Lee, 2012). However, Garcia-Sanchez et al. (2013) in their research explain that there are at least three key aspects that must be considered in government effectiveness, namely, organizational environment, organizational characteristics, and political characteristics. The first aspect, organizational environment, explains that having a well-educated and trained population of employees in government institutions can improve public administration’s volume of information (Tolbert et al., 2008). Additionally, in relation to organizational environment, high economic capacity and education status within the government can improve public sector reforms. These statements are further reinforced by issues of sluggish, bureaucratic reform in developing countries, which is usually caused by public employees’ weak economic quality and education level (Lee & Whitford, 2009). Countries struggling with economic instability often experience difficulties in recruiting employees and maintaining the quality of their organizational environment (infrastructure, processes, practices), and this consequently affects the absorption of information and public sector reforms (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2013). Hence, organizational environment is, undoubtedly, one of the key aspects that needs to be considered.

The second aspect, organizational characteristics, generally pertains to the complexities found in public organizations (diversity). Various studies explain that size is, commonly, a major variable in organizational characteristics. Size is a crucial part of organizational characteristic since a state’s size often represents a government’s level of resources and public services (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2013). A state of considerable size usually has better trained employees, a larger budget, and well-established departments (Norris & Moon, 2005). However, discussions relating to diversity are currently associated with age, gender, and nationality, which are measured through a comprehensive understanding of situational or environmental needs (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2013). As a result, gender diversity is frequently discussed in social contexts, given its benefits and drawbacks, as well as its impact on organizational success (Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., 2010). Gender diversity helps enhance creativity and innovation, as well as lead problem solving efforts in more effective directions (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2013).

The final aspect is political characteristics, which is also an essential part of government effectiveness. Politicians play a major role in shaping the future of public administration. Generally, such influences are shown in political ideology, stability, and rivalry (Barro, 1996). However, representations of developing and developed countries have differing characteristics, which subsequently lead to frequent debates regarding the matter due to limited success in empirical studies. As a result, political characteristics are often directed at measuring the viability of policy change in a country’s political institution, the preferences of actors, and alignment of each participant’s varying preferences with a country’s needs (Henisz & Zelner, 2010).

2.2.4 Regulatory quality

Regulatory quality is understood as the government’s capacity to formulate and implement its policies/regulations relating to the development sector (Kaufmann et al., 2010). In general, regulatory quality identifies how governments articulate and execute policies capable of supporting and promoting investments in the private sector (Umar & Nayan, 2018). Research by Nistotskaya and Cingolani (2015) shows that positive correlation between bureaucratic structure and regulatory quality can generate good economic growth by enhancing entrepreneurial development. Bureaucrats are said to be less responsive to policy changes, less productive, more focused on inputs, and more formal in their processes when access to people management is restricted (Nistotskaya & Cingolani, 2015). Thus, transparency in the recruitment process and access to bureaucracy may encourage better regulatory quality.

Good regulatory quality can reinforce economic growth in a country. A study by Umar and Nayan (2018) indicates that poor regulatory quality directly influenced the investment market in Africa. The global economic crisis eventually generated significant changes in Africa’s financial market structure and led to a sharp decline in market capitalization. Given the issues, extensive policy reform was required in Africa in order to anticipate rejection of investors coming to Africa (Umar & Nayan, 2018). Good regulatory quality achieved through investor–friendly policy reform is considered beneficial for raising a country’s market competitiveness and keeping the country away from financial crises (Nistotskaya & Cingolani, 2015; Umar & Nayan, 2018).

2.2.5 Rule of law

The meaning of the rule of law depends on how contestable, normative problems and related controversies are resolved (Rabinovych, 2020). Human rights is key for attaining a substantive understanding of the rule of law. It is introduced to various academic fields and international organizations amidst a lack of discussion regarding other important components in rule of law (democratic law-making, justice, legal culture, etc.). Currently, the rule of law has various meanings, and has not yet been clearly defined (Kochenov et al., 2016; Palombella, 2014; Rabinovych, 2020); however, there are at least five aspects that can provide a common understanding about rule of law (Stein, 2009).

-

1.

All members of society, including government officials, are subject to the law.

-

2.

The law is predictable and known. Laws apply equally to all in similar circumstances. Laws are defined and government discretion is limited enough to prevent arbitrariness.

-

3.

All citizens have the right to contribute to the development of laws that govern their actions.

-

4.

The law is fair and preserves everyone's rights and dignity. Legal processes are robust and accessible to enable independent legal profession enforcement of these principles.

-

5.

Judges make decisions based only on the facts and law of individual cases, not on the executive or legislative powers.

2.2.6 Control of corruption

Corruption is a phenomenon that frequently occurs in developing countries. It is also one of the main barriers to economic growth (Cieślik & Goczek, 2018). Corruption can also slow progress by limiting the buildup of human capital and increasing inefficient resource allocation by corrupt officials seeking to maximize their rent-seeking potential (d’Agostino et al., 2016a, 2016b; Tanzi & Davoodi, 2002). Several studies have subsequently classified corruption into three tiers—incidental, systematic, and systemic (Asongu, 2013). Incidental corruption commonly involves only one small group by employing models of favoritism and discrimination via the manipulation of the rules. One form favoritism is nepotism (Banuri & Eckel, 2012). Systematic corruption is usually more organized, involving most of the group members in a project such as public officials, intermediaries, and business people. Lastly, systemic corruption is a more structured type of corruption. It involves the entire group in a project or scandal (Asongu, 2013).

A few studies have argued that corruption is a market phenomenon that continues to develop and will tend to remain in countries with minimum risk. It also has a direct effect in reducing clean investments (Cieślik & Goczek, 2018). Prior research explains that corruption may impede growth due to its influence on investments in an open economy by way of thwarting international investments and establishing the mindset that corruption functions as one of the “levies” in entrepreneurship and productive action (d’Agostino et al., 2016a). International investors need not invest in nations with high levels of corruption if they are suitably diversified. Therefore, a control on issues of corruption is necessary in order to avoid the various significant problems they may cause.

Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov (2016) formulated several aspects to control corruption, which include interactions between resources and constraints, namely, administrative obstacles, budget transparency, trade openness, judicial independence, media freedom, and e-citizenships. Administrative obstacles refer to the time and procedures required to start a business or to pay taxes in a country. Budget transparency refers to the ease of access that the public has to the central government’s budget proposal. Trade openness concerns the length of time and the amount of procedures needed to conduct import/export activities. Judicial independence refers to the assessment of the judiciary’s independence from influences of government, citizens, or firms. Media freedom concerns the extent of the media’s role in accessing or publishing information. Lastly, e-citizenship covers the extent of access to information via the internet that the public has in relation to various government activities (Mungiu-Pippidi & Dadašov, 2016). Several of these aspects have been used to measure the level of corruption in a country. They function as controls in looking at the level of corruption in a country. If all six aspects are able to operate positively, then corruption in that country can be properly controlled (Mungiu-Pippidi, 2018).

3 Research methods

Data used in the present research was retrieved from public and official databases provided by the WHO (https://covid19.who.int/table) and World Bank (http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/Home/Reports). Data from the WHO was used to gain time series information pertaining to cumulative data of COVID-19 cases in every country for new positive cases and fatalities. Data from the World Bank was used to gain information concerning good governance indicators in the respective countries, covering:

-

1.

Voice & Accountability: the public’s freedom to express their opinions and accountable public officials;

-

2.

Political Stability & Lack of Violence: political stability and low level of violence;

-

3.

Government Effectiveness: effectiveness of the government in conducting its duties and functions;

-

4.

Regulatory Quality: quality of law and regulations;

-

5.

Rule of Law: practice of law enforcement; and

-

6.

Control of Corruption: controlling corruption.

The average values of the good governance indicators (covering the six criteria above) were subsequently sought among the arranged dataset from the World Bank. As for the WHO dataset, the following were pursued: (a) ratio between total confirmed deaths and total confirmed cases; and (b) ratio between total recovered cases and total confirmed cases. Similarly, the World Bank classified countries by their income. For every income category, a country ranking was made based on the case fatality rate (CFR—ratio between total deaths and total confirmed cases) so that radar charts of the six indicators from the top ten countries with the lowest CFR in each category could be obtained.

We classified countries into four income categories based on the World Bank's classification of economies: low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high income. On July 1, the categories are updated based on the previous year's GNI per capita in USD (using the Atlas method exchange rates).

GNI per capita (USD):

-

Low income = < 1,036

-

Lower-middle = 1,036—4,045

-

Upper-middle income = 4,046—12,535

-

High Income = > 12,535

We only employ three of the four groups (lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income nations) in conjunction with the World Bank's 2020 classification of countries. Low-income countries were excluded from our study since they have a common political distraction that contributes to a slew of difficulties in their country, even before the Covid-19 (Guzel et al., 2021; Kordas et al., 2018; Miranda et al., 2008). We are concerned that the commonalities between low-income groups will introduce bias into this research. When confronted with Covid-19, we likewise have limited knowledge about this group, which is why we use only three countries from the World Bank's income categories. The primary classifications are by geographic location, income group, and World Bank Group operational loan categories. These classifications fluctuate throughout time, depending on the evolution of each category in each country.

Datasets from the WHO and the World Bank were modified according to countries and years based on the time series to ease the process of analysis. Countries were selected based on six good governance indicators and then cross-sectioned to be distributed into four quadrants. The data used to create the quadrants were the case fatality rate and the values of each indicator. The horizontal axis indicates the average case fatality rate of the respective countries while the vertical axis lies exactly at zero since some of the good governance indicators have negative values.

X and Y variables made use of data processed from the World Bank and WHO sources, which resulted in the positions of the 4 quadrants as presented in Fig. 1 above. Each quadrant implies the following understanding:

-

Quadrant 1: CFR and indicators are poor, below average (Y is below average).

-

Quadrant 2: CFR is above average, but Y indicator is below average.

-

Quadrant 3: CFR and indicators are above average.

-

Quadrant 4: CFR is below average, but indicators are above average,

We began by collecting data on 270 existing countries. Then, using systematic sampling from populations with trend components (Sayed & Ibrahim, 2018), we calculated a country's capacity to handle COVID cases based on the comparison of "total recovered: total case," so that values ranged from zero (failed to handle) to one (capable of managing) (success in handling). Numbers range from zero to one for each of these 270 countries. Because we were looking for nations with the best case management, we opted to investigate which countries had a treatment level of 0.9–1, which resulted in a sort-list of approximately 33 countries. We attempt to analyze the relationship between the 33 countries' outcomes and the good-governance indicators in order to determine if there is a pattern connecting the good-governance indicators and case handling. The current study merely focuses on quadrant 3. The top 33 countries representing the World Bank and the WHO indicators were selected and processed. Quadrant 3 is considered to consist of the best countries in tackling COVID-19 cases. Thus, it is expected to provide the best practices for handling COVID-19 cases. The application used in data processing was Tableau Desktop 2020.3 free license edition for academic purpose. This application is considered capable of mapping and representing data visualization and analyses required in the research process.

4 Results

In the present study, the countries are categorized into three classifications: high income countries; upper-middle income countries; and lower-middle income countries. According to the World Bank, the classification was classified using gross national income (GNI) per capita, which is calculated annually in US dollars using a three-year average exchange rate. The income classification is used in World Development Indicators (WDI) (Fantom & Serajuddin, 2016). Such classification was done because there are unique characteristics in each issue of the respective country groups in the process of handling COVID-19, particularly when analyzed using the good governance indicators. Based on the WHO data, there are several countries with good performance in handling COVID-19 (nearing a cumulative score of 1.0), such as Singapore and New Zealand; however, countries with good COVID-19 responses are usually dominated by high-income countries. Meanwhile, upper-middle and lower-middle income countries still confront various challenges in the process of handling COVID-19. This may also be observed in the fact that, despite their resource constraints, low and middle-income countries have essentially chosen the same lockdown response strategy as high-income countries (Eyawo et al., 2021). This study analyzes each country’s performance in handling COVID-19 by integrating the cumulative recovered cases and cumulative positive cases of the three country classifications with the respective good governance indicators.

4.1 Voice and accountability

As previously explained, the current study divides country response to COVID-19 into 4 quadrants. In the figure above, it is apparent that in terms of voice and accountability indicator, Quadrant 3 (Q3) is dominated by high income countries like Iceland, Finland, Greenland, and Chile (Fig. 2). Voice and accountability is one of the indicators carried out by the government in order to establish or maintain compliance by providing assurance to the public (Torgler et al., 2011). Upon observation of the above figure, it can be construed that the governments of some of the countries in Q3 have, indeed, been able to maintain the public’s trust throughout their handling of the pandemic. For example, Finland found itself confronted with issues regarding local face mask production at the onset of COVID-19 (IFJ, 2020).

Originally, Finland was not a country that had high-quality local face mask production. However, at the beginning of the COVID-19 transmission, the Finnish government began to establish a collaborative scheme through public–private partnerships with a number of private companies to produce and supply high-quality face masks throughout the whole of Finland (IFJ, 2020). The public–private partnership scheme has, indeed, been known to assist governments in fulfilling public needs that have not been met (Fauzi & Kusumasari, 2020). This was what the Finnish government had done to fulfil the need for high-quality face masks in the country, as well as provide assurance to the Finnish public concerning the government’s handling of COVID-19 by satisfying the need for medical devices (Mankki et al., 2021).

There are two dimensions found in accountability, answerability and enforceability, and both dimensions require transparency in their implementation (Moore & Teskey, 2006). In reality, transparency is a problem in Q1 and Q2 countries (in Fig. 1), which are countries with weak/below average voice and accountability index. As an example, results from a study by George et al. (2020) indicate that there are more COVID-19 positive cases in children in Brunei Darussalam in comparison to other existing information. The study found six COVID-19 positive cases in children who were previously not diagnosed with COVID-19 (George et al., 2020). Providing assurance through assessment and transparency carried out by each government is considered of the utmost importance in the process of handling COVID-19. This is done to increase public trust in the government’s efforts to tackle the pandemic (Cole et al., 2021; Song & Lee, 2016; L. Zhang et al., 2020). Hence, providing public assurance through government performance and transparency is deemed extremely crucial in the voice and accountability indicator.

4.2 Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism

In terms of the political stability and absence of violence/terrorism indicator, there is no significant difference compared to the previous indicator. Similar to the Q3 of the voice and accountability indicator, the Q3 pertaining to the political stability and absence of violence/terrorism indicator is also dominated by high-income countries, such as Greenland and New Zealand (see Fig. 3). Meanwhile, developing countries tend to dominate in Q1/Q2 areas, with only one developing country situated in the Q3 area, which is Dominican Republic. In case of the current study on COVID-19, political stability is the most essential element as it directly affects the process of handling the pandemic. As previously explained, the issue of political stability is indeed often confronted by developing countries and has direct impact on various aspects of a country (Khan & Akbar, 2013; Kim, 2010; Kurecic & Kokotovic, 2017). This has been corroborated through the present study by showing Q1 and Q2 results dominated by developing countries (upper-middle and lower-middle income). It is undeniable that politics is truly the most influential aspect in every issue that unfolds in developing countries.

An example is the case in Malaysia, where the country still carried out general election activities by holding political campaigns and assembling various parties (including the public) (Jayaraj et al., 2021). One example is the political campaign activities in the Sabah election held from the 12th to the 25th of September 2020 followed by a general election on the 26th of September 2020. After these events, there was quite a significant rise of COVID-19 cases in Sabah due to political activities involving various parties on the ground and the rather heated political contestation occurring in the region (Lim, 2020). Although Malaysia has generally had a good experience in handling COVID-19 (as shown by the WHO score), in reality, political stability remains as a problem, causing COVID-19 transmission in the country. Accordingly, good political stability is considered a substantial part of a country (particularly its government) so that it does not affect other aspects, such as the handling of a pandemic, which is the focus of this study.

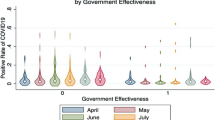

4.3 Government effectiveness

In terms of the government effectiveness indicator, it is apparent that high-income countries are very dominant in Q3, which is similar to the previous indicators. However, there is a difference wherein no upper-middle countries are positioned in Quadrant 3 of this particular indicator. The upper-middle income countries are all placed in the Q2 group, while Q3 includes countries like Singapore, New Zealand, and Iceland (Fig. 4). It is important to evaluate the organizational environment and political factors relating to government effectiveness (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2013). In countries included in the Q3 group, the three aspects of government effectiveness have certainly been well considered.

As an example, when we look at Singapore’s organizational environment, it has well-educated and trained public employees. This is verified by results of a study carried out by Vidyarthi et al. (2020) which argues that, in terms of handling the pandemic, Singapore has prepared its public employees (particularly those in hospitals) to face the pandemic by holding various remote simulations far before the appearance of COVID-19. Additionally, the needs of (public) health workers in Singapore are also guaranteed, be it economic needs or supporting facilities for employing health measures (Kuguyo et al., 2020). Upon observation of Singapore’s political characteristics, it also shows positive support in handling COVID-19, which is corroborated by the government’s preparedness in fulfilling all the public and health workers’ needs throughout the process of handling the pandemic (Ansah et al., 2021) Thus, good government effectiveness is capable of assisting the response to the pandemic by ensuring the availability of adequate facilities and infrastructure.

4.4 Regulatory quality

The regulatory quality indicator in good governance refers to the government’s capacity in formulating and implementing policy/regulation (Umar & Nayan, 2018). There are a number of high-income countries situated in the Q3 group of this indicator: Singapore; New Zealand; Ireland; China (Macau); and Greenland (Fig. 5). Singapore is, once again, positioned in Q3 because has the capacity for good governance in formulating and implementing policies, specifically policies related to the handling the pandemic.

Following Singapore’s failure to deal with SARS in 2002, its Ministry of Health immediately formulated a policy to create 900 public health preparedness centres for rapid response (PHPC) across the country when the initial COVID-19 cases appeared in Wuhan (Kuguyo et al., 2020). The government of Singapore also created policies to screen or test residents with the flu at the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak and to strengthen existing public health facilities in the country (Vidyarthi et al., 2020). In addition, China is also included in the Q3 group under this indicator. It is irrefutable that China was one of the first countries that reported positive COVID-19 cases, yet the government’s response in formulating and implementing policies is considered outstanding.

China implemented a total lockdown policy following the COVID-19 outbreak in the country in order to halt human mobility (including the spread of the virus) throughout the country (AlTakarli, 2020). This policy has been strictly implemented by the Chinese government, and it has been proven effective in significantly reducing the level of COVID-19 transmission in the country (Butler, 2020; Wade, 2020). Additionally, The Chinese government has taken steps to combat the pandemic by maximizing the collaboration of public and private sectors (Abbas et al., 2021). Private companies produced masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE), and the government helped the private sector through the subsidies. A government’s ability to implement their policies is, without a doubt, influential in their level of success in dealing with a particular problem. In the case of the lockdown policy, for instance, not all countries that applied such a policy succeeded in resolving the COVID-19 transmission in their country. In some countries, the lockdown policy had, instead, resulted in other problems such as economic crisis (Butler, 2020).

4.5 Rule of law

For the rule of law indicator, not many countries are included in the Q3 group; among them are New Zealand and Greenland (Fig. 6). New Zealand is indeed recognized as one of the countries with the least amount of COVID-19 positive cases in the world, and the lowest of the 37 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (Baker et al., 2020). With strong leadership, comprehensive initiatives, regular communication, and an engaged, empowered, and enabled populace, New Zealand can suppress COVID-19 cases (Penaloza, 2020).

At the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, New Zealand was able to gradually control all the COVID-19 clusters in the country and suppress additional cases within several weeks (Penaloza, 2020; SCMP, 2020). When the second outbreak occurred in August, New Zealand, which did not have any additional COVID-19 cases in three months, had to suffer a second round indicated, among others, by the emergence of a new cluster in Auckland (SCMP, 2020). The New Zealand government immediately isolated the three citizens who tested positive for COVID-19 and carried out an aggressive contact tracing program on all its residents (Penaloza, 2020). The New Zealand government also requested its citizens commit to another lockdown (WHO, 2021). As previously explained, rule of law demonstrates a government’s capacity in defining/analyzing a problem and finding a solution to that problem. The New Zealand government, in this case, was able to move aggressively by analysing the spread of COVID-19 and resolving the problem. It is thus undeniable that New Zealand can be categorized as a country with good performance under the rule of law indicator.

4.6 Control of Corruption

Regarding the control of corruption indicator, groups Q1 and Q2 are still dominated by upper-middle and lower-middle countries. Some countries, like Dominica, Granada, Malaysia, and Mongolia, are still confronting a rather complex issue concerning the control of corruption (based upon observation of Fig. 7). As previously explained, corruption is a phenomenon that often occurs in developing countries. It is one of the main problems in economic growth (Cieślik & Goczek, 2018). The issue at hand is that the advent of COVID-19 affects the control of corruption in some countries situated as upper-middle or lower-middle countries. The presence of the pandemic is, instead, taken advantage of by a number of elites in some countries to avoid corruption issues.

The case in Malaysia is an example of the current pandemic being used by a particular group to avoid corruption trials. The former PM's trial was postponed on October 5 due to his 14-day self-quarantine following his return from aiding Barisan Nasional's election campaign in Sabah on September 27 (Lim, 2020). The corruption case, with 25 charges involving an elite state official in Malaysia, had to be delayed due to a required self-quarantine that had to be carried out. This, undoubtedly, violates one of the aspects in the control of corruption, namely judicial independence (Mungiu-Pippidi & Dadašov, 2016), wherein the judiciary should not allow his participation in campaign activities in Sabah, seeing that there was still an ongoing corruption case investigation. The pandemic should not hamper all ongoing legal processes. The public courts/attorneys should be more firm in conducting legal investigations, and the process should not be obstructed by any reason.

4.6.1 Good governance based on country classification

4.7 High-income countries

The top ten high-income countries with the highest score, in terms of comparing good governance indicator with CFR, are Singapore, Qatar, Bahrain, Cayman Islands, Oman, Iceland, UAE, Kuwait, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. It is undeniable that countries with strong economic stability, which is typical of high-income countries, tend to have good government effectiveness (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2013). Such a statement is conclusively corroborated by the results of this study, which demonstrate quite a high score in government effectiveness compared to other indicators.

Singapore is ranked first in the current study. It also has the highest government effectiveness score at 2.23. Prior research mentions that a high level of government effectiveness may be supported by a strong sense of nationalism that policy makers or decision makers maintain (Ahlerup & Hansson, 2011). This is also verifiable from the effectiveness of the Singapore government, where the government of Singapore displayed a very high sense of nationalism when we observed its organizational environment and characteristics. Aside from the role and support given by Singapore’s Ministry of Health in dealing with COVID-19 (as previously explained in the government effectiveness section), a strong sense of nationalism demonstrated by the Singapore government is also apparent from their regret about the country’s failure in facing the past pandemic.

The failure of the Singaporean government to combat the 2003 SARS pandemic forced them to plan numerous policies and infrastructural assistance well in advance of the emergence of the COVID-19 (Vidyarthi et al., 2020). Accordingly, it is undeniable that high-income countries typically have strong government effectiveness because, apart from the support of their country’s economic stability, their policy makers also, commonly, have a high sense of nationalism, which subsequently results in policy making that generates decisions based on state interests and public needs (Ahlerup & Hansson, 2011; Whitford & Lee, 2012).

4.8 Upper-middle income countries

As for the group of upper-middle income countries, the top ten countries in this study are Botswana, Namibia, Maldives, Gabon, Costa Rica, Belarus, Venezuela, Kazakhstan, Jordan, and Paraguay. Although these countries are positioned at the top in terms of comparing good governance indicators against CFR, in reality, some of these countries still maintain unsatisfactory results when we look at their individual good governance indicator scores. Venezuela, for instance, scored minuses in every good governance indicator, with the lowest score in the rule of law indicator (-2.34). However, based on the average of all the countries, voice and accountability is the weakest indicator in the group of upper-middle countries with a score of -0.409. It is undeniable that there are various issues within the scope of the government in upper-middle countries, particularly in the process of handling COVID-19.

Venezuela is a case in point. The country has been facing various legal and regulatory issues throughout the COVID-19 period. As previously explained, rule of law should prioritize the aspect of human rights in both theory and practice (Rabinovych, 2020), but, in reality, the cases unfolding in Venezuela indicate various human rights violations during the handling of COVID-19. Venezuelan authorities have unlawfully jailed and prosecuted scores of journalists, healthcare workers, human rights lawyers, and political opponents since declaring a state of emergency amidst Covid-19 in mid-March 2020 (Human Rights Watch, 2020). Detainment without solid plausible reasons undoubtedly violates the key aspect in rule of law, which is human rights. This issue eventually intersects with voice and accountability, wherein such action leads to shutting down the public’s capacity to express their opinions and interests, which are commonly directed to influence government priority or its decision making process (O’Neil et al., 2007).

Rule of law, voice, and accountability are crucial issues taking place in upper-middle countries because, in reality, these aspects also hinder the process of handling COVID-19 in certain countries. As explained with the Venezuelan example above, weak legal and regulatory capacities have a negative influence in the process of handling COVID-19, which is indicated by the continuous rise of positive cases and excessive fear among the populace. The restricted means available for conveying aspirations by the public or non-government parties also leads to weak evaluation and innovation in facing the COVID-19 pandemic. Conclusively, various improvements in these aspects are required for countries in the upper-middle group so they are able to enhance their government’s performance in facing the pandemic.

4.9 Lower-middle income countries

Lower-middle income countries may be regarded as underdeveloped countries that usually undergo various, more complex economic and social problems than countries in the other groups (High and upper-middle income countries). The top ten lower-middle income countries in the study are Nepal, Sri Lanka, Ghana, West Bank and Gaza (Palestinian Territory), Uzbekistan, Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Cabo Verde, Djibouti, Bangladesh, and Zimbabwe. Out of the six good governance indicators, government effectiveness has the lowest average, with a score of -0.576 when based on the total average of the 10 countries. Lower-middle income countries are faced with quite considerable challenges in relation to quality of public services and employees, as well as the government’s commitment and credibility. The lack of policy makers or decision makers’ sense of nationalism in the group of lower-middle income countries also undermines government effectiveness in such countries (Ahlerup & Hansson, 2011).

Furthermore, in the case of Nepal, regulatory quality has the lowest score at -0.75. A study by Chaudhary (2020) also states that there are still weaknesses in the quality of policy formulation and implementation in the Nepalese government to support the health sector and resolve the issue of poverty. Consequently, Chaudary’s study supports the results of this study, which indicate that regulatory quality is indeed a problem that is currently being faced by Nepal in handling issues of health, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic. Conclusively, government effectiveness and regulatory quality remain a problem often confronted by lower-middle income countries.

5 Conclusion

As the world is still facing a time of crisis amidst the COVID 19 pandemic, essential questions must be asked of what collective lessons on governance implementation have been learned from this situation. Since the WHO declared the unique SARS-CoV-2 virus a global health emergency, governments around the world are still using emergency powers to exclude and suspend normal governmental functions. By recognising the importance of adhering to good governance practices, this study found that countries that have succeeded in managing the COVID-19 pandemic are the ones that have good indicators of good governance, namely, voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. Furthermore, in high-income countries and upper-middle countries, indicators, such as control of corruption, have become the most influenced from other factors, while in lower and middle countries, the most influential indicator is voice and accountability.

We believe our research will shed light on the government's performance in numerous countries during the pandemic. Nonetheless, we are cognizant of the paper's limitations. To begin, we did not analyse every country in detail; rather, we focused on a few key countries. Second, we excluded the lower income group from our research due to a lack of data on this group and the rationale that included this group would introduce bias into our findings (because of the similarities in political problems that previous research finds on these group). Perhaps future research can do in-depth analyses of several countries that were not very prominent in our study. We believe that other countries that are not as prominent in our research have a unique difficulty in comparison to those countries that we thoroughly analyse. Future studies might also examine the performance of governments in low-income nations in the event of a pandemic. The findings of this study will allow for the validation of theories from prior research demonstrating striking commonalities in low-income countries. Despite the limits of our study, we believe that our research will contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field of public administration, particularly in terms of public sector performance during crisis. Additionally, we anticipate that our research will contribute to knowledge advancement in the field of crisis governance.

References

Abbas, H. S. M., Xu, X., Sun, C., Gillani, S., & Raza, M. A. A. (2021). Role of Chinese government and public-private partnership in combating COVID-19 in China. Journal of Management and Governance. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-021-09593-7

Adebola, B. Y. (2021). Microfinance banks, small and medium scale enterprises and COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. European Journal of Economics, Law and Politics, 8(2), 1–10.

Adivar, B., & Selen, E. S. (2013). Review of research studies on population specific epidemic disasters. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal., 22(3), 243–64.

Afayo, R., Buga, M., Alege, J. B., Akugizibwe, P., Atuhairwe, C., & Taremwa, I. M. (2019). Performance of epidemic preparedness and response committees to disease outbreaks in Arua District, West Nile Region. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1437920

Ahlerup, P., & Hansson, G. (2011). Nationalism and government effectiveness. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39(3), 431–451.

AlTakarli, N. S. (2020). China’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak: A model for epidemic preparedness and management. Dubai Medical Journal, 3(2), 44–49.

Ansah, J. P., Matchar, D. B., Shao Wei, S. L., Low, J. G., Pourghaderi, A. R., Siddiqui, F. J., Min, T. L. S., Wei-Yan, A. C., & Ong, M. E. H. (2021). The effectiveness of public health interventions against COVID-19: Lessons from the Singapore experience. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248742.

Asongu, S. (2013). Fighting corruption when existing corruption-control levels count: What do wealth-effects tell us in Africa? Institutions and Economies, 5(3), 53–74.

Baker, M. G., Wilson, N., & Anglemyer, A. (2020). Successful elimination of Covid-19 transmission in New Zealand. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(8), e56.

Banuri, S., & Eckel, C. (2012). Experiments in culture and corruption: A review. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Retrieved, from http://econ.worldbank.org. Accessed on 30 Jan 2021.

Barro, R. J. (1996). Determinants of economic growth: A cross-country empirical study. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge.

Boin, A., & Hart, P. (2003). Public Leadership in Times of Crisis: Mission Impossible? Public Administration Review, 63(5), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00318

Boin, A., Hart, P., & Kuipers, S. (2018). The crisis approach. In H. Rodrguez & W. Donner (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research (pp. 23–38). Springer.

Boin, A., Hart, P. T., Mcconnell, A., & Preston, T. (2010). Leadership style, crisis response and blame management: The case of hurricane katrina. Public Administration, 88(3), 706–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01836.x

Boin, A., McConnell, A., & Hart, P. (2008). Governing after crisis: The politics of investigation, accountability and learning. Cambridge University Press.

Boubaker, S., & Nguyen, D. K. (2018). Governance issues in business and finance in the wake of the global financial crisis. Journal of Management & Governance, 22(1), 1–5.

Bromfield, N., & McConnell, A. (2021). Two routes to precarious success: Australia, New Zealand, COVID-19 and the politics of crisis governance. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(3), 518–535.

Butler, J. (2020). The force of nonviolence: An ethico-political bind. Verso

Chan, J.F.-W., Kok, K.-H., Zhu, Z., Chu, H., To, K.K.-W., Yuan, S., & Yuen, K.-Y. (2020). Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 9(1), 221–236.

Chaudhary, D. (2020). Prospect of good governance and human development in Nepal. Open Journal of Political Science, 10(02), 135.

Choi, J. Y. (2020). COVID-19 in South Korea. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 96(1137), 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137738

Cieślik, A., & Goczek, Ł. (2018). Control of corruption, international investment, and economic growth–Evidence from panel data. World Development, 103, 323–335.

Cole, A., Baker, J. S., & Stivas, D. (2021). Trust, Transparency and Transnational Lessons from COVID-19. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(12), 607.

Cossin, D., Botteron, P., & Lu, H. (2020). The Good Governance Crash Test Covid 19

d’Agostino, G., Dunne, J. P., & Pieroni, L. (2016a). Corruption and growth in Africa. European Journal of Political Economy, 43, 71–88.

d’Agostino, G., Dunne, J. P., & Pieroni, L. (2016b). Government spending, corruption and economic growth. World Development, 84, 190–205.

Dai, B., Fu, D., Meng, G., Liu, B., Li, Q., & Liu, X. (2020). The effects of governmental and individual predictors on COVID-19 protective behaviors in China: A path analysis model. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 797–804.

Deslatte, A., Hatch, M. E., & Stokan, E. (2020). How can local governments address pandemic inequities? Public Administration Review, 80(5), 827–831.

Eyawo, O., Viens, A. M., & Ugoji, U. C. (2021). Lockdowns and low-and middle-income countries: building a feasible, effective, and ethical COVID-19 response strategy. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00662-y

Fantom, N. J., & Serajuddin, U. (2016). The World Bank’s classification of countries by income. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7528.

Fauzi, F. Z., & Kusumasari, B. (2020). Public-private partnership in Western and non-Western countries: a search for relevance. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMPC-08-2019-0071

Fay, D. L., & Ghadimi, A. (2020). Collective bargaining during times of crisis: Recommendations from the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 815–819.

Garcia-Sanchez, I. M., Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., & Frias-Aceituno, J. (2013). Determinants of government effectiveness. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(8), 567–577.

George, S., Ansari, M. S., Kalliath, A., Khan, M. J., Abdullah, M. S., Asli, R., Momin, R. N., Mani, B. I., Chong, P. L., & Chong, V. H. (2020). COVID-19 in children in Brunei Darussalam: Higher incidence but mild manifestations. Journal of Medical Virology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26310

Gisselquist, R. M., & Resnick, D. (2014). Aiding government effectiveness in developing countries. Public Administration and Development, 34(3), 141–148.

Gloppen, S., Rakner, L., & Tostensen, A. (2003). Responsiveness to the concerns of the poor and accountability to the commitment to poverty reduction. Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Goetz, A. M., & Jenkins, R. (2002). Voice, accountability and human development: The emergence of a new agenda. Human Development Report Office (HDRO), United Nations Development Programme

Goodman, C. B., Hatch, M. E., & McDonald, B. D., III. (2021). State preemption of local laws: Origins and modern trends. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 4(2), 146–158.

Gu, M. (2017). Good governance and judicial review in Hong Kong. The Chinese Journal of Comparative Law, 5(2), 398–419.

Gupta, S., Nguyen, T. D., Rojas, F. L., Raman, S., Lee, B., Bento, A., Simon, K. I., & Wing, C. (2020). Tracking public and private responses to the COVID-19 epidemic: evidence from state and local government actions. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Guzel, A. E., Arslan, U., & Acaravci, A. (2021). The impact of economic, social, and political globalization and democracy on life expectancy in low-income countries: are sustainable development goals contradictory? Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01225-2

Hamblin, R. L. (1958). Leadership and crises. Sociometry, 21(4), 322–335.

Henisz, W. J., & Zelner, B. A. (2010). The hidden risks in emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 88(4), 88–95.

Hermans, M. A., Fox, T., & van Asselt, M. B. A. (2012). Risk governance. In S. Roeser, R. Hillerbrand, P. Sandin, & M. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of Risk Theory (pp. 1093–1117). Springer.

Héroux, S., & Fortin, A. (2013). Exploring information technology governance and control of web site content: A comparative case study. Journal of Management & Governance, 17(3), 673–721.

Human Rights Watch. (2020). Venezuela: A Police State Lashes Out Amid Covid-19 (Arbitrary Arrests, Prosecutions of Critics, Abuses Against Detainees). Human Rights Watch. Retrieved, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/28/venezuela-police-state-lashes-out-amid-covid-19. Accessed on 28 Jan 2021.

IFJ. (2020). COVID-19 Update: Suominen partners with fellow Finnish companies to ensure supply and authenticity of facemasks in Finland. International Fiber Journal. Retrieved, from https://fiberjournal.com/covid-19/. Accessed on 15 Jan 2021.

Janssen, M., & Van Der Voort, H. (2016). Adaptive governance: Towards a stable, accountable and responsive government. Editorial. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.02.003

Janssen, M., & Van Der Voort, H. (2020). Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.02.003

Jayaraj, V. J., Rampal, S., Ng, C.-W., & Chong, D. W. Q. (2021). The Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Malaysia. The Lancet Regional Health-Western Pacific, 17, 100295.

Jing, Y. (2021). Seeking opportunities from crisis? China’s governance responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. International Review of Administrative Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320985146

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 5430

Kettl, D. F. (2020). States divided: The implications of American federalism for COVID-19. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 595–602.

Khan, M. M., & Akbar, M. I. (2013). The impact of political risk on foreign direct investment. International Journal of Economics and Finance. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v5n8p147

Kim, H. (2010). Political stability and foreign direct investment. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 2(3), 59–71.

Kochenov, D., Magen, A., & Pech, L. (2016). Introduction: The great rule of law debate in the EU. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(5), 1045–1049.

Kock, N., & Gaskins, L. (2014). The mediating role of voice and accountability in the relationship between Internet diffusion and government corruption in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Information Technology for Development, 20(1), 23–43.

Kordas, K., Ravenscroft, J., Cao, Y., & McLean, E. V. (2018). Lead exposure in low and middle-income countries: perspectives and lessons on patterns, injustices, economics, and politics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112351

Kuguyo, O., Kengne, A. P., & Dandara, C. (2020). Singapore COVID-19 pandemic response as a successful model framework for low-resource health care settings in Africa? Omics: A Journal of Integrative Biology, 24(8), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030022

Kurecic, P., & Kokotovic, F. (2017). The relevance of political stability on FDI: A VAR analysis and ARDL models for selected small, developed, and instability threatened economies. Economies, 5(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030022

Lee, S.-Y., & Whitford, A. B. (2009). Government effectiveness in comparative perspective. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 11(2), 249–281.

Lim, I. (2020). Covid-19 interruptions: The court cases in Malaysia (briefly) disrupted by quarantine, tests. Malay Mail. Retrieved, from https://malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/10/10/covid-19-interruptions-the-court-cases-in-malaysia-briefly-disrupted-by-qua/1911299. Accessed on 4 Jan 2021.

Mankki, L., Lehto, I., Hirvonen, H., & Jokinen, E. (2021). The Economic Impact Of Covid-19 On The Finnish Regional Health Care Services

Martin, B. (2013). Effective crisis governance. In: L. Starke, et al. (Eds.), State of the World 2013: Is Sustainability Still Possible? (pp. 269–278). Washington, DC: Island Press-Center for Resource Economics.

McMullin, C., & Raggo, P. (2020). Leadership and governance in times of crisis: A balancing act for nonprofit boards. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49(6), 1182–1190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020964582

Miranda, J. J., Kinra, S., Casas, J. P., Davey Smith, G., & Ebrahim, S. (2008). Non-communicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 13(10), 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02116.x

Moore, M., & Teskey, G. (2006). The CAR Framework: Capability, Accountability, Responsiveness. What Do These Terms Mean, Individually and Collectively? A Discussion Note for DFID Governance and Conflict Advisers. 29 October 2006. Retrieved, from https://paperzz.com/doc/8890463/the-car-framework--capability--accountability--responsive. Accessed on 10 Jan 2021.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2018). Seven steps to control of corruption: The road map. Dædalus, 147(3), 20–34.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A., & Dadašov, R. (2016). Measuring control of corruption by a new index of public integrity. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 22(3), 415–438. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00500

Nistotskaya, M., & Cingolani, L. (2015). Bureaucratic structure, regulatory quality, and entrepreneurship in a comparative perspective: Cross-sectional and panel data evidence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(3), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv026

Norris, D. F., & Moon, M. J. (2005). Advancing e-government at the grassroots: Tortoise or hare? Public Administration Review, 65(1), 64–75.

O’Neil, T., Foresti, M., & Hudson, A. (2007). Evaluation of citizens’ voice and accountability: review of the literature and donor approaches. Department for International Development.

Palombella, G. (2014). The EU’s sense of the rule of law and the issue of its oversight. Retrieved, from https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/33857/RSCAS_2014_125.pdf?sequence=2. Accessed on 12 Jan 2021.

Pasape, L., Anderson, W., & Lindi, G. (2015). Good governance strategies for sustainable ecotourism in Tanzania. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1065834

Paudel, N. R. (2020). COVID 19 Outbreak and Impact on Governance System. Society of Management and Governance Policy Research Center.

Penaloza, M. (2020). New Zealand declares victory over Coronavirus again, lifts Auckland restrictions. National Public Radio (NPR). Retrieved, from https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/10/07/921171807/new-zealand-declares-victory-over-coronavirus-again-lifts-auckland-restrictions. Accessed on 27 Jan 2021.

Prinsloo, F. C. (2013). Good governance in South Africa: A critical analysis. University of Stellenbosch.

Rabinovych, M. (2020). The rule of law as non-trade policy objective in EU preferential trade agreements with developing countries. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 12(3), 485–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-020-00145-z

Rodríguez-Domínguez, L., García-Sánchez, I.-M., & Gallego-Alvarez, I. (2010). Explanatory factors of the relationship between gender diversity and corporate performance. European Journal of Law and Economics, 33(3), 603–620.

Rosenthal, U., Boin, A., & Comfort, L. K. (2001). Managing crises: Threats, dilemmas, opportunities. Charles C Thomas Publisher.

Rosenthal, U., Charles, M. T., & Hart, P. (1989). Coping with crises: The management of disasters, riots, and terrorism. Charles C Thomas Pub Limited.

Sayed, A., & Ibrahim, A. (2018). Recent developments in systematic sampling: A review. Journal of Statistical Theory and Practice, 12(2), 290–310.

Schomaker, R. M., & Bauer, M. W. (2020). What drives successful administrative performance during crises? Lessons from refugee migration and the Covid-19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 845–850.

SCMP. (2020). Coronavirus: New Zealand loses Covid-free status again; Australian state eases restrictions. South China Morning Post. Retrieved, from https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/australasia/article/3105981/coronavirus-new-zealand-loses-covid-free-status-again. Accessed on 25 Jan 2021.

Shadmi, E., Chen, Y., Dourado, I., Faran-Perach, I., Furler, J., Hangoma, P., Hanvoravongchai, P., Obando, C., Petrosyan, V., & Rao, K. D. (2020). Health equity and COVID-19: Global perspectives. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z

Som, P. (2020). Determinants of Good Governance for Public Management in Cambodia. Journal of Service Science and Management, 13(01), 168.

Song, C., & Lee, J. (2016). Citizens’ use of social media in government, perceived transparency, and trust in government. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(2), 430–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1108798

Ssebunya, A. K. (2014). Why local realities matter for Citizens’ Voice and Accountability. Lessons from Mwananchi Uganda pilot projects. Field Actions Science Reports, 11, 1–7.

Stein, R. (2009). Rule of law: What does it mean. Minnesota Journal of International Law, 18, 293–303.

Tanzi, V., & Davoodi, H. (2002). Corruption, public investment and growth. Governance, Corruption and Economic Performance. International Monetary Fund.

Tolbert, C. J., Mossberger, K., & McNeal, R. (2008). Institutions, policy innovation, and E-Government in the American States. Public Administration Review, 68(3), 549–563.

Torgler, B., Schneider, F., & Macintyre, A. (2011). Shadow economy, voice and accountability, and corruption. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Umar, B., & Nayan, S. (2018). Does regulatory quality matters for stock market development? Evidence from Africa. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 8(4), 10.

Unerman, J., & Bennett, M. (2004). Increased stakeholder dialogue and the internet: Towards greater corporate accountability or reinforcing capitalist hegemony? Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(7), 685–707.

Vidyarthi, A. R., Bagdasarian, N., Esmaili, A. M., Archuleta, S., Monash, B., Sehgal, N. L., Green, A., & Lim, A. (2020). Understanding the Singapore COVID-19 experience: Implications for hospital medicine. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 15(5), 281.

Wade, F. (2020). Judith Butler on the Violence of Neglect Amid a Health Crisis: A conversation with the theorist about her new book. The Force of Nonviolence, and the need for global solidarity in the pandemic world. The Nation, May 13, 2020. Retrieved, from https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/judith-butler-force-of-nonviolence-interview/. Accessed on 29 Jan 2021.

Weinberg, N., & Grogan, J. (2020). Effective Pandemic Management Requires the Rule of Law and Good Governance. Verfassungsblog – On Matters Constitutional, 2366–7044. Retrieved, from https://verfassungsblog.de/effective-pandemic-management-requires-the-rule-of-law-and-good-governance/. Accessed on 28 Jan 2021.

Whitford, A., & Lee, S.-Y. (2012). Disorder, dictatorship and government effectiveness: Cross-national evidence. Journal of Public Policy, 32(1), 5–31.

WHO. (2020). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved, from https://covid19.who.int/table. Accessed on 5 Jan 2021.

WHO. (2021). COVID‐19 health system response monitor: New Zealand

Wilder-Smith, A., Chiew, C. J., & Lee, V. J. (2020). Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(5), e102–e107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8

Zafarullah, H., & Huque, A. S. (2001). Public management for good governance: Reforms, regimes, and reality in Bangladesh. International Journal of Public Administration, 24(12), 1379–1403.

Zhang, X., & Huang, R. (2021). The role of social media in public crisis governance. E3S Web of Conferences, 253

Zhang, L., Li, H., & Chen, K. (2020). Effective risk communication for public health emergency: Reflection on the COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) outbreak in Wuhan China. Healthcare, 8(1), 64.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kusumasari, B., Munajat, M.E. & Fauzi, F.Z. Measuring global pandemic governance: how countries respond to COVID-19. J Manag Gov 27, 603–629 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-022-09647-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-022-09647-4