Abstract

Objectives

Worry and loneliness looms large in American schools, especially in the social years of early adolescence where friendships are in flux and children strive to fit in and do well academically. We examine a nationally-representative sample of American 5th graders to document the extent of academic worry and loneliness, its costs for academic performance, and how social class can disrupt or exacerbate its associations.

Methods

Based on a nationally representative longitudinal survey (ECLS-K 2010–2011) of childhood (N = 5750), we examine if a child’s self-reported worry and loneliness are associated with standardized math and reading scores using OLS regression. We explore whether these associations vary by socioeconomic status.

Results

We find that academic worry is a strong predictor of math and reading skill. The association is amplified for disadvantaged students. Patterns hold when accounting for a host of other factors and are replicated in the ECLS-K 1998–1999. Loneliness and its association with math and reading performance was not statistically significant.

Conclusions for Practice

As academic worry is negatively associated with standardized math and reading skills, practitioners can be especially attuned to how these patterns are amplified for children in low socioeconomic households. Utilizing a nationally representative survey of early adolescence, we show that worry (and less so loneliness) is associated with math and reading skills and that these associations are moderated by socioeconomic status—disadvantaged students have a higher negative association with math and reading performance when they worry about their academic performance compared to advantaged students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is full of new anxieties and worry (Songco et al., 2020). Research has shown the negative impact of these socioemotional experiences on academic outcomes (Turney & McLanahan, 2015; Wenz-Gross et al., 1997)—specifically loneliness, stress, and academic pressure (Reiss, 2013; Songco et al., 2020). As much of this research has shown how socioemotional experiences impact academic outcomes in the middle school years (Turney & McLanahan, 2015; Wenz-Gross et al., 1997), much less is known about how these experiences impact youth in early adolescence—as children conclude elementary school (Reiss, 2013; Songco et al., 2020). Early adolescence is an important developmental stage both socially and biologically, and represents the onset of socioemotional skills and experiences that set the stage for the often turbulent years of middle school (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Ladd & Ettekal, 2013; London & Ingram, 2018).

In addition, we focus on the disproportionate impact of socioemotional experiences for socioeconomically disadvantaged children—children in households with low income and parents with low levels of education and occupational prestige. Children growing up in low-socioeconomic homes are more likely to experience family conflict, separation, household crowding, and neighborhood disorder (Johnson et al., 2016). These kinds of stressors increase the risk of anxiety, loneliness and depression (Maes et al., 2019; Spence et al., 2002). Likewise, a child’s internalizing problem behaviors—high anxiety, loneliness, sadness, and low self-esteem (McLeod & Kaiser, 2004)—vary by social class (Letourneau et al., 2013; Slopen et al., 2010; West et al., 2020) and are linked to the risk of high school dropout and lower levels of academic achievement (McLeod & Kaiser, 2004). Other socioemotional struggles, such as emotional well-being (Sznitman et al., 2011), school belonging (London & Ingram, 2018), and stress (Goodman et al., 2012) show similar patterns.

To date, research on children’s socioemotional experiences, such as peer anxieties, social and academic self-concept (how children view their friends and their performance in school), and internalizing/externalizing problem behaviors, have had limited sociological insight—specifically how a child’s family background might influence these outcomes (Bain & Bell, 2004; Calarco, 2018; Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Conger et al., 2010; Sewasew & Schroeders, 2019; Wentzel, 2017; Wu et al., 2021). We offer an important addition to this scholarship by specifically examining academic worry and loneliness—an understudied dimension of a child’s socioemotional development (Songco et al., 2020). Understanding these connections may elevate the importance of early intervention for all children—and especially socioeconomically disadvantaged children—and can be a critical way to enhance their long-term well-being (Okano et al., 2020).

In line with the literature, we pursue two hypotheses. First, worry and loneliness will be associated with children’s math and reading development in 5th grade. And second, the “costs” of these socioemotional struggles will be magnified in socioeconomically disadvantaged homes compared to socioeconomically advantaged homes.

Data and Methods

Sample

We use the ECLS-K 2010–2011 collected by NCES (Najarian et al., 2019; Tourangeau et al., 2015).Footnote 1 These data are a nationally representative sample of 16,450 students who were enrolled in kindergarten in the fall of 2010. The ECLS-K used a multistage probability sampling design in which PSUs were sampled, then roughly 1000 schools were sampled within each PSU, and about 20 students within each school were selected. Children’s socioemotional experiences were self-reported by fifth graders in 2016 (ages 10–11). Measures of socioeconomic status, child health, disability, gender, race/ethnicity, family structure and BMI were collected in the first waves in the school year 2010–2011. Measures of peer relationships, peer victimization, academic self-concept were measure at the end of 3rd grade. Assessments of math and reading skill were collected at the end of kindergarten and 5th grade. All other measures were collected from the child, parent or teacher in the 5th grade wave of data. We note that when available in the data, using the same measures in different waves did not change the patterns we observe.

Measures

Math and Reading Scores

The math assessment measures skills in conceptual knowledge and problem solving using questions about number sense, properties, and operations; measurement; geometry and spatial sense; data analysis, statistics, and probability; and patterns, algebra, and functions. The reading assessment includes questions measuring basic skills (e.g., word recognition), vocabulary knowledge, and reading comprehension. Reading comprehension questions asked the child to identify information specifically stated in text (e.g., definitions, facts, supporting details); to make complex inferences within texts; and to consider the text objectively and judge its appropriateness and quality. Both math and reading assessments use item-response methods (IRT) to gauge the level of difficulty, discriminating ability, and “guess-ability” of each item (Najarian et al., 2019; Tourangeau et al., 2015). We also accounted for early math and reading skill at the end of kindergarten as controls. These kindergarten assessments are correlated with later assessments (5th grade) at .72 for math and .59 for reading.

Socioemotional Struggle

We examine socioemotional struggles using two school-centric assessments of child worry and loneliness. We should note that these measures are not conventional operationalizations of worry and loneliness, as most metrics focus on general anxiety and depression scales that are often developed from adult-centered constructs (Songco et al., 2020). Our worry about school measures were child-reported in fifth grade. Students were asked “How true is each of these things about you? “I worry about taking tests,” “It's hard for me to finish my school work,” “I feel ashamed when I make mistakes at school,” “I worry about doing well in school,” and “I worry about finishing my work.” Item response options were: 1 = not at all true, 2 = a little bit true, 3 = mostly true, 4 = very true.” We factored these items, with a reliability coefficient of 0.71. Our child feels lonely measures were also child-reported. Students were asked “Think about yourself and your experiences this school year. How often do the following things happen? “I feel lonely at school,” “I feel left out at school,” and “I feel alone at school.” Item response options were: 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = very often. Items were factored with a reliability coefficient of .89.

Socioeconomic Status

This measure was computed at the household level using data from parents in fall 2010 or spring 2011. SES is a composite measure of the following: the father’s and mother’s (or guardians) highest education level, the father’s and mother’s (or guardians) occupational prestige scores, and household income. We transformed the continuous measure of SES into a percentile measure for ease of comparison between the highest and lowest SES quintiles.

Related Factors

Social and academic self-concept (how children view their friends and their performance in school) impacts a child’s emotional well-being and academic performance (Bain & Bell, 2004; Sewasew & Schroeders, 2019; Wentzel, 2017; Wu et al., 2021). As a result, we also include measures of social and academic self-concept in our analyses to determine if worry and loneliness have an independent relationship to academic outcomes at 5th grade with these measures in the model. Social concept is measured by the child’s assessment of peer relationships (at 3rd grade) (“I have lots of friends”, “I make friends easily”, “I get along with other kids easily”, “I am easy to like”, “Other kids want to me to be their friend”, and “I have more friends than others” with response options of 1 = not at all true, 2 = a little bit true, 3 = mostly true, 4-very true), school belonging (5th grade) (How often “I feel I fit in at school”, “I feel close to classmates”, “I feel close to teachers”, “I enjoy being at school, and “I feel safe at school” with response options of 1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always) and peer victimization (3rd grade) (Child reported that others teased child/called them names, others told lies about child, others have pushed/shoved child, others have excluded child with response options of 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = very often).

Academic self-concept is measured by the child’s assessment of their interest and performance in school (assessed at the end of 3rd grade). Children were asked if they are “good at science/math/reading”, if they “enjoy doing work in science/math/reading”, if they are “interested in science/math/reading”, if they “cannot wait to do science/math/reading”, and if they “like science/math/reading.” Response options were 1 = not at all true, 2 = a little bit true, 3 = mostly true, 4 = very true. Responses from each domain (science, math, reading) were factored with an alpha score of .82.

Given that we assess children in an era of strong social media influences (Adelantado-Renau et al., 2019; Downey & Gibbs, 2020), we also include measure for the child’s self-reported frequency of texting, messaging, and emails, frequency of online gaming, and frequency of using social networking sites at the end of 5th grade. Response options were 1 = never, 2 = less than once a week, 3 = a few times a week, 4 = about once a day, 5 = many times a day.

Confounding Factors

Our socioemotional measures of worry and loneliness may be proxies for unmeasured, but related factors. We account for this possibility by including a strong set of potentially confounding factors, including both child and parental characteristics (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007; Gershoff et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2016; Whittle et al., 2017). One pronounced way advantaged homes might offset the academic costs of socioemotional struggles is through concerted cultivation—the active development of a child’s talents by organizing daily activities to foster a child’s self-efficacy and accustom children to the pressures of performance and evaluation (Lareau, 2011). We operationalization concerted cultivation as an additive measure of parental involvement at home and school, and the frequency of extracurricular activities and trips (Bodovski & Farkas, 2008; Downey & Gibbs, 2020). For the measure of home involvement, parents (guardians) were asked the following; “In a typical week, how often the parent or any other family members did the following things with child? Tell stories, help with arts and crafts, play games or do puzzles, and talk about nature or do science projects.” Response categories for each item were; 1 = not at all, 2 = once or twice a week, 3 = 3 to 6 times a week, and 4 = every day. Extracurricular activities is a measure of the following whether the child participated in music lessons, art classes or lessons, organized clubs or recreational programs, organized athletic activities, drama classes, and organized performing arts programs. For each response, 1 = yes, 0 = no. Trips is based on the following question, “In the past month, has anyone in the family done the following with the child: visited a library or bookstore, visited an art gallery, museum, or historical site, visited a zoo, aquarium, or petting farm, gone to a play, concert, or other live show, or attended an athletic or sporting event?” For each response, 1 = yes 0 = no. Finally school involvement measures whether the parent or the other adults in the household attended an open house or back-to-school night, attended a meeting of a PTA or PTO, attended a school or class event, served as a volunteer in the classroom or elsewhere in the school, and gone to a regularly-scheduled parent-teacher conference. For each response, 1 = yes 0 = no.

We also account for homework effort. We use the following measures of how often the parent (guardian) checks for completed homework (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = always), how often child does homework at home (1 = never, 2 = less than once a week, 3 = 1–2 times a week, 4 = 3 to 4 times a week, 5 = 5 or more times a week), how often the parent or guardian helped with homework (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = always) and how often the parent or guardian knows how much homework the child has (child-reported) (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = very often, 6 = always).

For child characteristics, we include measures of school belonging (parent-reported), child grit (teacher-reported), approaches to learning (teacher-reported), and internalizing problem behaviors (teacher-reported). School belonging is measured with the following questions, “How often would you say that child complains about going to school, asks to stay home from school, seems to dread going to school, and makes up reasons to stay home from school? Responses ranged from 1 = almost never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = a lot, and 5 = almost always. Alpha score = 0.86). For child grit, teachers were asked how often the child showed eagerness to learn new things, easily adapted to changes in routine, persisted in completing tasks (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = very often) and how often the child worked to the best of his or her ability (1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = usually, 4 = always). Alpha score = .77. Approaches to learning captures a child’s citizenship in the classroom by asking the teacher if the child keep belongings organized, shows eagerness to learn new things, works independently, easily adapts to changes in routine, persists in completing tasks, pays attention well, and follows classroom rules. Each item was factored for a reliability coefficient of .92. Finally, we account for internalizing problem behaviors, developed from the original Social Skills Rating System. We use the teacher-rated assessments of the child’s anxiety, loneliness, low self-esteem, and sadness with a reliability coefficient of .79.

Control Measures

We account for several other factors as controls in our models. For female, information was collected from schools and confirmed by parents in subsequent waves. If inconsistent, the most recent parent reporting of sex was used, 0 = male, 1 = female. For race/ethnicity, parents were asked whether or not their child was Hispanic or Latino and to indicate to which of five race categories (White, Black or African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native) their child belonged. Parents could also select if their child belonged to more than one race category. For the measure of family structure, we use a measure for the number of siblings in the household (1 = 1, 2 = 2, 3 = 3, 4 = 4 plus) and a measure of the parents/guardians relationship status, 1 = two biological/adoptive parents and 0 = one biological/adoptive parent, one other parent/partner, one biological/adoptive parent only or other guardians.

We also account for child health characteristics. Child Disability is measured by asking parents (guardians) about their child’s ability to be independent and take care of himself or herself, ability to pay attention and learn, overall activity level, overall behavior and ability to relate to adults and children, emotional or psychological difficulties, ability to communicate, difficulty in hearing and understanding speech, and eyesight. If parents (guardians) indicated that their child had any issues or difficulties in response to these questions, they were asked to indicate if a diagnosis was obtained by a professional. If so, 1 = yes and 0 = no. Child BMI was calculated by multiplying the child’s weight by 703 and dividing by the square of the child’s composite height (Najarian et al., 2019; Tourangeau et al., 2015). Finally, child poor health was measured by asking parents (guardians) about their child's health; 1 = excellent, 2 = very good, 3 = good, and 4 = fair or poor.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were performed in Stata 17. Because dependent variables are continuous, we used Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. We employed wave-specific weights to produce estimates of population parameters. Using recommended NCES procedures (NCES 2022), data weighting adjustments for attrition and complex sampling resulted in 5,750 cases. Missing data ranged from 0 to 27% across measures. We used multiple imputation procedures (20 data files, 150 burn-ins) to account for missingness using the MI command (Stata 2021).Footnote 2

Results

Unweighted sample characteristics are reported in Tables 1 and 2 (also see Appendix Table 6). In Table 1, math and reading assessments are standardized with a means of about 0 and standard deviations of about 1.Footnote 3 In line with literature, there are large socioeconomic differences in math and reading scores between the highest and lowest socioeconomic quintiles (math kindergarten 1.17 SD score gap (.57 + .60 = 1.17) and 5th grade 1.23 SD score gap (.63 + .60 = 1.23), p < .001) (reading kindergarten 1.08 SD score gap (.50 + .58 = 1.08) and 5th grade 1.21 SD score gap (.64 + .57 = 1.21), p < .001).

Table 2 reports sample characteristics for our socioemotional measures of worry and loneliness (Appendix Table 5 reports nationally representative estimates). Combining the categories of “mostly true” and “very true,” 46% the sample worries about tests (43% for the national estimate), 18% (16% for the national estimate) report that it is hard to finish work, 31% feel ashamed about making mistakes (31% for the national estimate), 48% report feeling worried about doing well (47% for the national estimate), and 41% worry about finishing work (40% for the national estimate). Across categories, socioeconomically disadvantaged students report more instances of worry than socioeconomically advantaged students.

Unlike academic worry, students are less prone to report high levels of loneliness with 8% of the sample reporting that they have felt lonely (8% for the national estimate), 7% that they have felt left out (8% for the national estimate), and 6% that they feel alone (< 1% for the national estimate). We find socioeconomic differences in the loneliness submeasures in the expected directions but they are less pronounced than worry.Footnote 4

Are Worry and Loneliness Associated with Children’s Math and Reading Development in 5th Grade?

Yes and no. With standardized math and reading scores as the outcome, OLS regression estimates reveal an important association between child-reported worry and loneliness with academic performance (see Tables 3 and 4). In bivariate modeling, we find a one standard deviation increase in child’s self-reported level worry is associated with a .39 standard deviation (p < .001) decrease in math performance and a .35 standard deviation (p < .001) decrease in reading (see Model 1 in Tables 3 and 4). In models with controls accounting for gender, family structure, child health and racial/ethnicity, we find a one standard deviation increase in child’s self-reported level worry is associated with a .20 standard deviation (p < .001) decrease in math performance and a .19 standard deviation (p < .001) decrease in reading (see Tables 3 and 4, Model 2). Likewise, a one standard deviation increase in child-reported feelings of loneliness is associated with a .08 (p > 05) and a .09 (p > .05) standard deviation decrease in math and reading scores, respectively (see Table 3 and 4, Model 2). Estimates change little in the full models (see Tables 3 and 4, Model 3) but loneliness is no longer significant. Overall, r-squared values are robust, ranging from .19 to .62 across models. High r-squared values are due to controls for previous math and reading performance, which are highly correlated with 5th grade math and reading performance.Footnote 5

Are the “Costs” of These Socioemotional Struggles Will be Magnified in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Homes Compared to Socioeconomically Advantaged Homes?

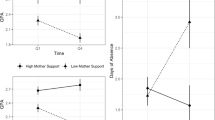

Yes and no. To test our second hypothesis, we created interaction terms reported in Tables 3 and 4 as “Socioeconomic Status X Worry” and “Socioeconomic Status X Loneliness.” These measures are the multiplication of socioeconomic status with worry and the multiplication of socioeconomic status with loneliness, a conventional approach to testing for moderating relationships between key variables (Hoffmann, 2016). In Model 1 (Tables 3 and 4), the interaction term Socioeconomic Status X Worry shows that for students in the highest socioeconomic quintile, there is a .24 reduction in the estimated .39 negative association between worry and math scores. In the full model (model 3), the − .16 association between worry and math scores is reduced by.12 standard deviations (p > .001) for children from the highest socioeconomic quintile—or in other words, children from the highest 5th quintile of socioeconomic status have virtually no penalty for worry for math and reading outcomes, an estimated .04 (.16 − .12 = .04) standard deviation decrease in their math scores and a .01 (.16 − .15 = .01) standard deviation decrease in their reading scores.Footnote 6Footnote 7 Together, we find effectively little to no cost of academic worry for socioeconomically advantaged student math and reading scores in 5th grade. On the other hand, the general interaction term for socioeconomic status and loneliness shows little evidence of a moderating pattern, suggesting that the negative relationship between the general measure of loneliness and math/reading scores (models 2 and 3) is not socioeconomically conditioned.

For robustness checks, we found the following.Footnote 8 First, the association and interaction patterns for worry and academic outcomes hold up across various measures of socioeconomic status when modeled in isolation (including father’s education level, occupational prestige and income, and the mother’s education level, occupational prestige, and income). Second, teacher-reported assessments of classroom performance produced patterns in the same direction as the NCES administered math and reading assessments, but few associations were statistically significant. Third, to examine if these patterns are time invariant, we replicated the same analyses using the ECLS-K 1998–1999 data collected twelve years earlier (2004). With nearly identical measures, we found surprisingly similar results. Forth, we examined whether our interaction patterns extended to interactions by race/ethnicity or gender. They did not. Fifth, as worry (but not loneliness) has a strong association with academic performance and reveal statistically significant interactions, we did not find these patterns when modeling internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors, or related measures including social and academic self-concept. And finally, (6) we did not find meaningful change in our results when using various transformations of our worry measures (e.g. raw scores, additive).

Discussion

This work is timely. For the year 2016, we find that about 36% of American 5th graders worry about aspects of school work, and about 5% report feeling lonely.Footnote 9 Our results could have important implications for growing socioemotional vulnerabilities of adolescent children in an era of increased educational challenges associated with COVID-19 (George et al., 2021; Kuhfeld et al., 2020). Most importantly, as socioeconomic achievement gaps in American schools may grow by up to 30% due to the global pandemic, any impact of a child’s socioeconomic background on socioemotional struggles and school achievement may be even more pronounced today (Duckworth et al., 2021; Haeck & Lefebvre, 2020; Hammerstein et al., 2021).

Overall, we argue that socioemotional struggles—specifically academic worry—matter for children’s academic performance in school. We find the following. First, a one standard deviation increase in worry is associated with about .39 standard deviation decrease in math and reading scores, and about a .16 SD decrease even when accounting for a strong set of potentially confounding factors. (Although the child’s feeling of loneliness show similar patterns, evidence is less clear.) To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first nationally representative sample to demonstrate these important relationships, especially in early adolescence (Songco et al., 2020). Second, we show that these patterns vary across the socioeconomic conditions children experience—disadvantaged kids almost exclusively feel this cost. And conversely, socioeconomically advantaged kids show remarkably little to no impact of academic worry. This suggests that disadvantaged youth have fewer supports to combat school anxieties—advantaged parents, for example, could be coaching their children to develop effective help-seeking behavior in the classroom when they struggle compared to disadvantaged children who more often internalize their failure (Calarco, 2018).

We should also note here that our results have limitations, we will mention two. First, our evidence is not causal. Measures for worry and loneliness were only available in the last wave of data (5th grade). Thus, we can only document associations. Nonetheless, this limitation may not be too critical—if the causal arrows were reversed, the impact of poor performance on socioemotional struggles would still be found to be more prevalent among disadvantaged students compared to their more affluent peers. And second, we rely on child self-reporting. Although knowing how children assess themselves is important (Varni et al., 2007), parent/teacher reports and qualitative assessments could reveal new insight and potentially divergent patterns from what we find in this study.

Implications

Since the 1990s, health care practitioners, policy makers and academics (Grason & Guyer, 1995) have advocated for better assessment and monitoring of maternal and child health. The maternal-child health framework advocates for public health monitoring systems, such as the Child Health Survey (supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau).Footnote 10 For example, section G of the Child Health Survey assesses the child’s schooling and activities (NSCH-T2, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2019) (see also Section F of the NSCH-T3). Here, we recommend including worry measures developed by NCES in the ECLS-K. Children could be asked the following: How true is each of these things about you? (1) I worry about taking tests, (2) It’s hard for me to finish my school work, (3) I feel ashamed when I make mistakes at school, (4) I worry about doing well in school, and (5) I worry about finishing my work with response options of 1 = not at all true, 2 = a little bit true, 3 = mostly true, 4 = very true. Also, we recommend pediatricians utilize screening instruments (i.e. SCARED, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2019) that assess a patient’s social class backgrounds and document their socioemotional experiences using child wellness screens, specifically academic worry.

Overall, we demonstrate with nationally representative data using a strong set of controls that negative socioemotional experiences (especially academic worry) in early adolescence matter for academic progress in school and are especially detrimental for disadvantaged kids who likely have limited supports at home to overcome setbacks. In an era of increased concern for children’s socioemotional development, we argue that earlier and better assessments/interventions may significantly enhance the welfare and academic outcomes of American youth, especially children in disadvantaged settings.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

This research is not based upon clinical study or patient data. This research was conducted in accordance with prevailing ethical principles and reviewed by an Institutional Review Board (IRB2021-344).

We explored if results were sensitive to our analytic approach. Using path analysis (SEM command in Stata), we found similar patterns.

Weighted results reveal slight variations in the standardization of math and reading scores and the quintile distribution of socioeconomic status.

Sample characteristics for factors related to worry and loneliness (child grit, approaches to learning, internalizing problem behaviors, social self-concept and academic self-concept) as well as measures for concerted cultivation, school belonging, homework effort and social media use are reported in Appendix Table 4. Patterns are in expected directions. Correlations between measures are reported in the Appendix Table 5.

To see what measures predict worry and loneliness, see Appendix Table 8.

As another way to understand how socioeconomic status interacts with academic worry, the association between worry and academic outcomes (math and reading) is strongest when analyzing the lowest SES quintile.

To understand which of the sub-items of academic worry has the strongest association with academic performance, we replicated model 2 (in Tables 3 and 4), but with each sub-item measured separately (see the Appendix, Table 9). We find that ashamed about mistakes has the most pronounced association with academic outcomes. For disadvantaged children, the association is about − .27 and − .25 for math and reading (b = − .20). But for advantaged children, this association is virtually erased (.20–.16 = .04 SD decrease for math; .20–.19 = .01 SD decrease for reading).

We focus on the measures of worry because loneliness estimates, as we report, were generally not statistically significant with worry as a control in our models.

Averaging our national representative estimates for each measure of academic worry and loneliness.

Our thanks to reviewers for providing these suggestions.

References

Adelantado-Renau, M., Moliner-Urdiales, D., Cavero-Redondo, I., Beltran-Valls, M. R., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., & Álvarez-Bueno, C. (2019). Association between screen media use and academic performance among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(11), 1058–1067.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED)—Parent Version. Retrieved May 24, 2022

Bain, S. K., & Bell, S. M. (2004). Social self-concept, social attributions, and peer relationships in fourth, fifth, and sixth graders who are gifted compared to high achievers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(3), 167–178.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148.

Bodovski, K., & Farkas, G. (2008). “Concerted cultivation” and unequal achievement in elementary school. Social Science Research, 37(3), 903–919.

Calarco, J. M. (2018). Negotiating opportunities: How the middle class secures advantages in school. Oxford University Press.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 685–704.

Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 10(58), 175–199.

Downey, D. B., & Gibbs, B. G. (2020). Kids these days: Are face-to-face social skills among American children declining? American Journal of Sociology, 125(4), 1030–1083.

Duckworth, A. L., Kautz, T., Defnet, A., Satlof-Bedrick, E., Talamas, S., Lira, B., & Steinberg, L. (2021). Students attending school remotely suffer socially, emotionally, and academically. Educational Researcher, 50(7), 479–482.

Fendrich, M., Weissman, M. M., & Warner, V. (1990). Screening for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: Validating the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for children. American Journal of Epidemiology, 131(3), 538–551.

Fomby, P., & Cherlin, A. J. (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review., 72(2), 181–204.

George, G., Dilworth-Bart, J., & Herringa, R. (2021). Potential socioeconomic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on neural development, mental health, and K-12 educational achievement. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(2), 111–118.

Gershoff, E. T., Aber, J. L., Raver, C. C., & Lennon, M. C. (2007). Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development, 78(1), 70–95.

Goodman, R. D., Miller, M. D., & West-Olatunji, C. A. (2012). Traumatic stress, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement among primary school students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(3), 252–259.

Grason, H. A., & Guyer, B. (1995). Public MCH program functions framework: Essential public health services to promote maternal and child health in America. Johns Hopkins University.

Haeck, C., & Lefebvre, P. (2020). Pandemic school closures may increase inequality in test scores. Canadian Public Policy, 46(S1), S82–S87.

Hammerstein, S., König, C., Dreisörner, T., & Frey, A. (2021). Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 4020.

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718.

Hoffmann, J. P. (2016). Regression models for categorical, count, and related variables: An applied approach. University of California Press.

Johnson, S. B., Riis, J. L., & Noble, K. G. (2016). State of the art review: Poverty and the developing brain. Pediatrics, 137(4), 1–16.

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., & Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Academic Achievement. EdWorkingPaper No. 20–226. Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University.

Ladd, G. W., & Ettekal, I. (2013). Peer-related loneliness across early to late adolescence: Normative trends, intra-individual trajectories, and links with depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1269–1282.

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press.

Letourneau, N. L., Duffett-Leger, L., Levac, L., Watson, B., & Young-Morris, C. (2013). Socioeconomic status and child development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 21(3), 211–224.

London, R., & Ingram, D. (2018). Social isolation in middle school. School Community Journal, 28(1), 107–127.

Maes, M., Nelemans, S. A., Danneel, S., Fernández-Castilla, B., Van den Noortgate, W., Goossens, L., & Vanhalst, J. (2019). Loneliness and social anxiety across childhood and adolescence: Multilevel meta-analyses of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1548–1565.

McLeod, J. D., & Kaiser, K. (2004). Childhood emotional and behavioral problems and educational attainment. American Sociological Review, 69(5), 636–658.

Najarian, M., Tourangeau, K., Nord, C., Wallner-Allen, K., & Vaden-Kiernan, N. (2019). Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010–11 (ECLS-K:2011), Third-Grade, Fourth-Grade, and Fifth-Grade Psychometric Report (NCES 2020–123). U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved Feb 10, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch.

National Survey of Children’s Health. (2019) US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Retrieved Nov 9, 2020, from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/nsch/tech-documentation/questionnaires/2019/NSCH-T2.pdf

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2022) Retrieved Feb 10, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/training/datauser/ECLS-K_04.html

Okano, L., Jeon, L., Crandall, A., Powell, T., & Riley, A. (2020). The cascading effects of externalizing behaviors and academic achievement across developmental transitions: Implications for prevention and intervention. Prevention Science, 21(2), 211–221.

Reiss, F. (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 90, 24–31.

Schober, P. M. D., Boer, C., & Schwarte, L. A. (2018). Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 126(5), 1763–1768.

Sewasew, D., & Schroeders, U. (2019). The developmental interplay of academic self-concept and achievement within and across domains among primary school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 204–212.

Slopen, N., Fitzmaurice, G., Williams, D. R., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Poverty, food insecurity, and the behavior for childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(5), 444–452.

Songco, A., Hudson, J. L., & Fox, E. (2020). A cognitive model of pathological worry in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(2), 229–249.

Spence, S. H., Najman, J. M., Bor, W., O’Callaghan, M. J., & Williams, G. M. (2002). Maternal anxiety and depression, poverty and marital relationship factors during early childhood as predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(4), 457–469.

StataCorp. (2021). Stata: Release 17. Statistical Software. StataCorp LLC.

Sznitman, S. R., Reisel, L., & Romer, D. (2011). The neglected role of adolescent emotional well-being in national educational achievement: Bridging the gap between education and mental health policies. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(2), 135–142.

Tourangeau, K., Nord, C., Lê, T., Sorongon, A. G., Hagedorn, M. C., Daly, P., & Najarian, M. (2015). Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010–11 (ECLS-K: 2011). User's Manual for the ECLS-K: 2011 Kindergarten Data File and Electronic Codebook, Public Version. NCES 2015−074. National Center for Education Statistics.

Turney, K., & McLanahan, S. (2015). The academic consequences of early childhood problem behaviors. Social Science Research, 54, 131–145.

Varni, J. W., Limbers, C. A., & Burwinkle, T. M. (2007). How young can children reliably and validly self-report their health-related quality of life?: An analysis of 8,591 children across age subgroups with the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes., 5(1), 1–13.

Wentzel, K. R. (2017). Peer relationships, motivation, and academic performance at school. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (pp. 586–603). The Guilford Press.

Wenz-Gross, M., Siperstein, G. N., Untch, A. S., & Widaman, K. F. (1997). Stress, social support, and adjustment of adolescents in middle school. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 17(2), 129–151.

West, M. R., Pier, L., Fricke, H., Hough, H., Loeb, S., Meyer, R. H., & Rice, A. B. (2020). Trends in student social-emotional learning: Evidence from the first large-scale panel student survey. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(2), 279–303.

Whittle, S., Vijayakumar, N., Simmons, J. G., Dennison, M., Schwartz, O., Pantelis, C., & Allen, N. B. (2017). Role of positive parenting in the association between neighborhood social disadvantage and brain development across adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(8), 824–832.

Wu, H., Guo, Y., Yang, Y., Zhao, L., & Guo, C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the longitudinal relationship between academic self-concept and academic achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1749–1778.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BGG did the analyses and framed the paper. He did a final literature drafting. EK did the initial literature review and reviewed the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gibbs, B.G., Kenealey, E. The Academic Cost of Worry Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Children. Matern Child Health J 26, 2137–2154 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03486-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03486-3