Abstract

Objectives

To inform updates to the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) design and processes, African American/Black and Hispanic/Latina women in Florida provided feedback on their awareness and perceptions of the PRAMS survey, and preferences for survey distribution, completion, design and content.

Methods

Focus groups were conducted in English and Spanish with 29 women in two large metropolitan counties. Participants completed a brief survey, reviewed the PRAMS questionnaire and recruitment materials, engaged in discussion, and gave feedback directly onto cover design posters.

Results

Participants reported limited awareness of PRAMS. Preferences for survey distribution and completion varied by participant lifestyle. Interest in topics covered by PRAMS was as a motivator for completion, while distrust and confidentiality concerns were deterrents. Participants were least comfortable answering questions about income, illegal drug use, and pregnancy loss/infant death. Changes to the length of the survey, distribution methods, and incentives/rewards for completion were recommended.

Conclusions for Practice

Results highlight the need to increase PRAMS awareness, build trust, and consider the design, length and modality for questionnaire completion as possible avenues to improve PRAMS response rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Significance

What is already known on this subject? Florida PRAMS data has not been released in over a decade due to low response rates. In order to increase responses rates, changes to PRAMS survey design and procedures may be necessary. What this study adds? This evaluation details the perceptions and opinions of women in the PRAMS priority populations (including Black and Hispanic mothers) on PRAMS materials, survey procedures, and incentives. The results from this study could be used to inform PRAMS procedures to improve survey response rates.

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiated the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) project in 1993, a population-based surveillance project conducted in partnership with 46 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Northern Mariana Islands, and Puerto Rico (CDC, 2022; Shulman, et al., 2018). The PRAMS aimed to further reduce infant morbidity and mortality by collecting information on maternal behaviors and experiences because research suggested that the United States infant mortality rate was no longer declining as rapidly as it had been in previous years (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). The data collected by the PRAMS is used to inform health departments and federal agencies on factors influencing health disparities among maternal and infant health populations as well as to assist in evaluating currently existing programs and policies concerning mothers and infants (CDC, 2021; Florida Health PRAMS, 2021; Shulman, et al., 2018). The survey has two parts, a 56-questions core component and a 10–30 question standard component of questions developed by either the CDC or the state site (CDC, 2021). The Florida Department of Health joined the state-based surveillance initiative in 1993 with the 68-question Phase II version of the PRAMS survey to collect information used for planning and evaluating maternal and child health programs tailored to pregnant women in Florida (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021).

Since its inception in 1993, the survey has been revised six times with the most current version being the 82-question Phase VII questionnaire (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). The Florida PRAMS survey includes the 56-question required core component asked by all PRAMS projects which addresses such topics as prenatal care, source of payment for prenatal care and delivery, smoking and alcohol consumption, family planning, breastfeeding, and complications of pregnancy. The remaining 26 standard questions cover Medicaid, maternal health problems, fertility treatments, HIV testing, folic acid, co-sleeping, and infections/diseases. The state-added questions include depression and sick-baby care (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). For data to be released, the response rate threshold was set at 70% but later lowered to 55% by the CDC to account for the decline in federal health survey response rates noted throughout the nation (CDC, 2021; Shulman, et al., 2018).

In Florida, PRAMS randomly samples approximately 2500 mothers who have given birth to a live-born infant each year (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). Participants are contacted through a mailed questionnaire 2–5 months are giving birth (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). This sample is drawn from an aggregate of all Florida resident births known to the state vital statistics office. Random samples are drawn from three strata of Florida resident births: (i) Black race/normal birth weight, (ii) Non-Black race/normal birth weight and (iii) Low birth weight (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). The Florida PRAMS is distributed primarily by mail with a phone call follow up for non-responders (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). Potential study participants receive a mailer between 2 and 5 months after the birth; a phone interview is conducted as a follow-up if no response is received from the mailed materials (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). Several attempts are made to contact sampled women including multiple mailings (pre-letter, first mailing, tickler letter, second mailing and third mailing) and up to 15 call attempts. The mailed questionnaire is self-administered and requires approximately 20 min to complete. The phone interview requires 25–30 min.

Despite the lowered response rate threshold, Florida PRAMS data had not been released since 2005 due to response rates below 55% (CDC, 2021). The unavailability of this data is problematic as PRAMS provides vital state-specific data that serves to monitor health behaviors, access to care, and receipt of services among recently pregnant women that can aid in identifying groups of women and infants at high risk for health problems (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021).Prior research has found that elements affecting survey response rates include: sociodemographic characteristics, awareness of PRAMS, consistent mailing address and telephone number, preferred mode of survey receipt (mail, phone, Internet), survey design content and response reminders (Binkley, et al., 2017; Brick & Williams, 2013; Holt et al., 1997; Shulman, et al., 2018; Stedman et al., 2019). In Florida, response rates are higher among women of white race, aged 30 years or older, married, with more than 12 years of education, who started prenatal care in the first trimester, and who had babies with normal birth weight, which is similar to other states (Florida Health, 2018; Shulman et al., 2018).

Our objective was to evaluate factors that may influence Florida PRAMS response rates, particularly among mothers at high risk for adverse birth outcomes, and to assess their perceptions of Florida PRAMS materials. Specific evaluation questions included: (1) Are women in the Florida PRAMS target population (Black, white, and Hispanic women who have given birth within the past 18 months) aware of PRAMS; (2) What types of survey distribution (mail, telephone, and internet) are preferred by Florida PRAMS target population; (3) What factors would increase the likelihood that Florida PRAMS will reach their target population; (4) What PRAMS questions are Florida PRAMS target population most/least comfortable answering?

Methods

Sample and Recruitment

Eligibility criteria included individuals who self-identified as female and gave birth within the past 18 months. Additional efforts were made to recruit participants that self-identified as Black/African American or Hispanic/Latina origin, as well as mothers with lower socioeconomic status, to hear from populations with lower PRAMS response rates. The study took place in two large Florida metropolitan areas, Hillsborough and Miami-Dade Counties. Purposive convenience sampling was used to recruit both English and Spanish-speaking participants. The evaluation team contacted agencies that provide services to diverse populations to aid in the recruitment process. These organizations—including a job training program, community development agency, and parenting support agency—disseminated recruitment flyers in both English and Spanish via email, social media, and in-person through community contacts serving individuals who met the inclusion criteria. The flyers notified potential participants of the nature of the study, eligibility requirements, and $20 gift card for participation.

Data Collection

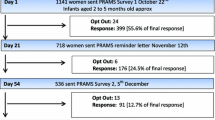

This study was reviewed and determined exempt by the [University] Institutional Review Board and is not based upon clinical study or patient data. The evaluation team was comprised of individuals with diverse racial, ethnic, regional, and social identities. All members of the evaluation team completed graduate coursework in qualitative data collection and analysis. The evaluation team developed a semi-structured focus group guide and visual aids to obtain participants’ opinions about the PRAMS mailing materials, survey questions, incentives/rewards for participation and the mode of completing surveys (Fig. 1, Table 1). The focus group guide and all other materials were translated to Spanish, reviewed by native Spanish speakers from multiple countries, and back-translated to ensure accuracy. Additionally, a demographic questionnaire gathered information on participant’s individual and family characteristics and their personal opinions on surveys. A PRAMS process flowchart was used as a visual aid to help participants understand each step in the process (Fig. 1). The focus group protocol was pilot tested with two separate groups of university students, who were of diverse racial and ethnic identities, with revisions to the protocol following each group. While piloting with the priority population is beneficial, this project’s pilot with university students helped to elicit open and honest constructive feedback on the step-by-step process of reviewing, notating, and commenting on the PRAMS materials presented as well as the moderators’ guide and protocol.

Focus Groups

Focus groups were conducted in community locations at dates/times convenient for the participants. Focus groups were conducted between December 2019 and February 2020. Participants provided informed consent prior to the conduct of each focus group. Prior to each discussion, participants provided verbal consent to be audio recorded and demographic surveys were completed to gather individual characteristic data. The focus group guide and process flow chart were used to facilitate the conversation. Focus groups were moderated by the principal investigator and three female graduate students on the evaluation team. Focus groups conducted in Spanish were moderated by two female graduate students on the evaluation team who self-identified as Hispanic. Focus group moderators had no previous relationships with the evaluation participants.

The questions used to guide the focus groups are included in Table 1. At the beginning of each focus group, the moderator explained the nature of the evaluation and why the focus group was being conducted. The moderator explained the PRAMS survey process, then elicited participants’ opinions on the process of survey and letter administration (e.g., number of times sent or contacted) and if the information on the letter provided was concise and easy to understand (Fig. 1). The second activity involved showing participants survey covers from other states (names of states were covered to prevent bias) on a poster (Fig. 2). Participants were asked to place a heart on what they liked and place an “X” on what they did not like, along with any additional comments. After participants finished marking the posters, a discussion ensued as to why they marked each survey the way they did. Next, participants were shown the Florida PRAMS survey and asked to comment on the cover (i.e., whether they found it aesthetically pleasing and suitable for what the survey represents), design, and if questions in the survey were appropriate and necessary. The focus groups lasted approximately thirty to sixty minutes, were audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim (Spanish recording translated to English). Following the conclusion of the focus groups, a $20 gift card was offered as a thank you for participation.

Applied thematic analysis was used to analyze the focus group data using qualitative coding with MaxQDA software. An initial codebook was created with a priori structural codes based on the purpose of the study and the focus group guide. Emergent codes were developed and incorporated as necessary throughout the analysis process. Three members of the evaluation team coded one focus group transcript separately, calculated kappa for individual codes, and discussed codebook revisions. This process was replicated until a kappa of ≥ .80 was reached and the codebook was finalized. The remaining transcripts were divided among the coders and coded separately using the finalized codebook. Similar codes were grouped into themes.

Several steps were taken to ensure the credibility of the research and maintain the trustworthiness of the data (Cope, 2014; Polit & Beck, 2020). Participant interactions and responses to facilitator questions were reflected upon during a debriefing session after each focus group. Focus group facilitators asked participants to clarify responses and summarized participants’ responses to ensure understanding when necessary. Authenticity and confirmability were established by providing quotes from all of the focus groups to represent the themes that emerged (Cope, 2014; Polit & Beck, 2020). The responses and feedback to our questions during the focus groups were not linked to any personally identifiable information. The COREQ criteria for reporting qualitative research informed the reporting of the methods and results of this evaluation (Tong et al., 2007).

Results

A total of 29 women participated in three English-speaking groups (n = 26, one group primarily with Black mothers and two groups with participants identifying as Black, White, and/or Hispanic) and one Spanish-speaking group (n = 3). Majority (38%) were between 20 and 25 years old, self-identified as non-Hispanic (55%) and Black (62%), and had a high school education or greater (97%) (Table 2). Nearly a third of participants were employed full-time, more than half reported that they were single, and 38% lived in a household with three or more children (Table 2).

Following completion of the demographic survey (Table 2), a brief opinion survey on their opinions of survey terminology and incentives to participate was distributed (Table 3). Very few participants were aware of PRAMS, though one noted that she had completed the survey in the past. When asked questions about the types of survey distribution preferred, nearly all participants suggested that the survey be offered in a variety of formats, such as online or in-person, in addition to mail or telephone. In our exploration of what factors would increase the likelihood that Florida PRAMS will reach the priority population, participants shared their opinions through the brief survey as well as the focus group discussions. On the survey, most participants reported the most likelihood of participating in projects referred to as “survey” (98%) or “questionnaire” (90%) and were least likely to participate in projects referred to as “surveillance” (8%) (Table 3).

After completing the opinion survey, participants reviewed and were asked questions about PRAMS materials (invitation letter, information card, survey) and asked to review and provide feedback on questions within the PRAMS survey. Factors that could affect participation, including which PRAMS questions participants would be most/least comfortable answering, were interwoven in discussions throughout the process of reviewing the survey and associated materials. Three themes emerged from the focus groups data: attitudes about PRAMS, motivation to complete the PRAMS survey, and recommendations to improve PRAMS response rates.

Attitudes About PRAMS

Understanding participants’ attitudes toward the Florida PRAMS materials was an important part of this evaluation. We therefore encouraged participants to openly share their perspective on all materials, including what they liked and/or aspects that stood out, and what was displeasing in any way. We received positive comments regarding the succinctness and readability of some of the materials shown. We also heard critiques of the survey design, exclusion of fathers, and the nature of some of the survey questions.

Positive Attitudes

Participants in all groups favored materials that were concise, direct and avoided jargon. Specifically, for the frequently asked questions card, some participants made statements such as: “Basically, what’s here is what you all want. It explains about the survey.” (Hillsborough Spanish Group). Many participants expressed positive attitudes about the readability of the survey in terms of font size and visual layout. Participants in two focus groups noted that the text was in a large font: “It is a nice size…You realize some people don’t see well if the words are too small.” (Miami Focus Group 1).

Attitudes Expressing Concern

Participants expressed some concerns regarding the survey design. The cover shown displayed only mothers holding a baby and participants suggested that a survey about maternal behaviors before, during, and after pregnancy should include a visibly pregnant woman on the cover. Moreover, participants suggested that images of fathers or families should be included. One participant, with agreement from others, felt that the use of images of solely women with their babies represented single mothers: “Yes, like this… maybe put a family photo, a father and his child, instead of all three single mothers.” (Hillsborough English Group). Another participant said “Yes, the dad’s nowhere to be included in any of it when in actuality, fathers do participate.” (Hillsborough English group).

Several participants felt that the survey was too long; that they simply would not have enough time to complete the entire survey. One participant, who incidentally had previously completed the Florida PRAMS survey, explained her experience as follows, “I feel like I finally got to maybe half of it when I got it and I was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s still going’.” (Hillsborough English Group). Participants across all groups believed that certain questions could be offensive to certain mothers, or too personal and uncomfortable to answer. One participant stated, “It’s like they’re low-key trying to get in your business.” in regard to the personal questions asked on the survey. PRAMS questions that inquired about income, other family members, whether the infant was currently living with the mother, the death of an infant, and the loss of a pregnancy were considered sensitive or offensive topics. As noted by participants in the Hillsborough English Group: “That’s like [question] 79. Why would we disclose our yearly total house income? Just too nosy for me.” and “Even [question] 49, ‘Is your baby living with you?’ That could be offensive too.” Another parent commented, “I don’t think a mom, you know, would want to read that, ‘Is your baby alive now?’”.

Motivation to Complete PRAMS

Factors that increased the motivation to complete the survey pertained to the invitation letter and the overall topic of the survey. Participants noted on the brief opinion survey that they were more likely to complete a survey if it was for a cause they cared about, if the survey material looked or sounded very official, or if they received “a decent reward” after completing the survey (Table 3). Discouragement from completing the survey primarily revolved around fears related to confidentiality and disclosing personal information.

Factors that Increase the Likelihood of Completing the Survey

The survey notification card was a helpful tool in motivating participants to open the survey. Participants in three of the four focus groups noted that receiving a letter from the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) or from Tallahassee (State capital) was recognized as official mail and motivated participants to at least open and read the invitation letter. As one participant put it, “Yes, anything from Tallahassee would make me open it; but yes, even with the health part, it was dealing with your child anyway…” (Miami Group 2).

The topic was another reason for opening the survey invitation. A number of women felt that since the survey was about pregnancy or children, they would want to know more about the survey. One mom stated, “There’s so much going on with the baby, so in the meantime, I look at everything.” (Miami Group 2). Many of the women felt that completing the survey may help with learning more about their baby or sharing their stories. Moms experiencing pregnancy for the first time, in particular, may want to find an outlet for sharing their experiences, which is helpful for them and for FDOH: “A lot of new moms, they want to express what they’re going through and that’s what you want.” (Miami Group 1).

Factors that Decrease the Likelihood of Completing the Survey

One important consideration, related to which PRAMS questions are Florida PRAMS target population most/least comfortable answering, is that participants did not believe that PRAMS is confidential as the state knows who the survey is sent to and whether participant has completed the survey. As one participant explained, “It’s not confidential when somebody knows that I filled that out with my name on it.” (Miami Group 1). Similarly, concerns were raised regarding the consequences to providing answers to personal questions. Another participant expressed their concerns about the Health Department’s ability to follow-up with survey respondents, “Well they’re the health department so if they are asking health questions then I’ll be concerned because there they have the opportunity to pry and to find you.” (Miami Group 1).

Distrust and fear also contributed to participants’ reasoning for not wanting to complete the survey, particularly with questions on topics such as illicit drug use. One participant stated, “I think that people who take strong drugs are not going to say they do. They won’t say it because that would have consequences. This is what people think. If I put down that I consume strong drugs, someone will find out.” (Hillsborough Spanish Group). Many of the women believed that respondents who may use drugs would not answer certain questions or provide dishonest responses out of fear that they would be reported to child protection services.

Recommendations to Improve PRAMS Response Rates

Participants reported several mechanisms for improving the PRAMS survey itself and the process to complete the survey. These recommendations would purportedly aid in increasing the response rate of the PRAMS survey. These recommendations included a method to opt out of the survey, a reduction in the number of survey questions, multiple response methods, and improving the visual appeal of the survey.

Recommendations for PRAMS Process

Participants preferred different modalities for survey distribution, which may underscore the need to offer multiple methods for completion due to the diversity in lifestyles among the target population. While some participants preferred a mailed paper survey, several women felt that completing the survey by phone or email may be better. In the Spanish-language focus group, some women preferred to complete the survey at the community center, where they normally come for activities and feel comfortable.

In addition to having multiple survey distribution methods, participants in one focus group wanted the option to opt out of the answering triggering/personal questions or completing the survey in the first place. These participants felt that opting out of the survey would reduce unwanted follow-up calls if they decide not to complete the mailed survey: “…what about putting ‘Yes, you would like to do the survey’ and ‘No, you would not like to do the survey’. Then you won’t have all those tags, calling them and calling them when they already going to let you know ‘No’ and then you go find somebody else.” (Miami Group 1).

Recommendations for Survey Design and Content

Participants noted that including more color in the survey booklet would be more attention-grabbing and encouraging. Suggestions included highlighting the header for each section in a bright color instead of gray, to keep participants attention as they progressed through the booklet, and adding bright, eye-catching colors—such as yellow, purple, or orange—to the cover of the survey booklet.

All groups noted that the survey was too long or laborious to complete: “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, there are a lot of questions.’ Maybe if it was like more limited, like something quick because I'm always on go. I’m barely home, barely have enough time to sit down.” (Hillsborough English Group). One concern was that the length of the survey may keep women from answering questions honestly and contribute to women selecting random answers just to complete the survey:

You can just mark whatever you want to and just send it back. If you want realistic answers you need to shorten up all these questions because the person is really like, 20 dollars is not going to make me sit down 20, 30 minutes to fill this out but if I really want it, I’m going to check, check, check whatever just send it off and you wouldn’t get my real, honest opinion about certain things. I just filled it out for a couple of dollars and I’ll just send it back (Miami Group 1).

Participants in one focus group suggested that having a comment box at the end of the survey may be helpful for participants to provide feedback about their experiences and how to improve the survey. Another suggestion to improve survey response rates, was for FDOH to form partnerships with hospitals or social workers who could assist in the process.

Recommendations for Incentives

Finally, participants offered several suggestions regarding incentives to complete the survey and rewards following participation. While preferences varied, most suggested items that could be used for the baby or for families, such as coupons (to Target, Walmart, Publix grocery, or Visa), baby book(s), bibs, refrigerator magnets, stickers, button/pin for clothes, diaper, onesie, or a blanket:

A lot of people already have lots of bibs and many little things. Something pretty is nice, but in this case, the person is interested in something more practical. The time you have to spend taking the survey doesn’t make you interested in a cute little something. Or maybe they could include something for you. Because I’m thinking it’s a chore…Maybe they could buy something cheap for you and send it, but I think coupons would work better (Hillsborough Spanish Group).

Discussion

Understanding the perceptions of African American/Black and Hispanic/Latina mothers of the PRAMS survey is of special interest because these women are disproportionately at higher risk for preterm birth, morbidity, and infant mortality and less likely to complete PRAMS. Florida PRAMS results inform programs directed towards preventing poor maternal, child and birth outcomes. Black and Latina mothers in Florida expressed that multiple factors determine whether a respondent will open and complete the survey, including mothers’ interest in supporting maternal and child health, trust and credibility of the source of the survey, tone and appeal of materials, and practicality (timing and burden of completing the survey). Factors such as the visual appeal of the survey and the engaging topic (babies and mothers) were found to increase the likelihood of survey completion (Edwards et al., 2002; Gilbert et al., 1999). Offering the survey completion in a variety of formats such as a mobile-friendly version, was recommended by participants in this project and supported by other research (Binkley et al., 2017; Brick & Williams, 2013; Ghandour, 2018). Respondents also noted that receiving the survey from an official/credible source (the Department of Health) was an important factor in deciding whether to respond. Beyond raising awareness of PRAMS in general, taking the time to consider the perspectives of diverse mothers in relation to their passion for children and family, desire for representation in materials (e.g. photos on the cover), and concerns about confidentiality.

As seen in other studies, participants indicated that they were less likely to complete the survey if they were unfamiliar with the PRAMS or if they feared confidentiality would be breached (Brick & Williams, 2013; Harrison et al., 2019). A novel finding was that the mailing materials were critical; recognition of the FDOH name on the PRAMS notification card and the absence of jargon in the invitation letter were motivators for opening the survey. However, within the survey, participants noted discomfort in answering many of the more sensitive questions, which has been noted in other studies (Holt et al., 1997; Stedman, et al., 2019). Moreover, participants felt the length of the survey (just over 80 questions, 26 of which are not required by the CDC) made it difficult to complete as they had competing priorities and suggested adding an option to “opt out” which would reduce the amount of follow-up contacts to uninterested individuals.

Informed by this project, the Florida PRAMS program made revisions to their materials to include bright and cheerful colors and a more contemporary design, as well as the tagline “mommies helping mommies” on the invitation flyers and letters, and survey. Florida PRAMS also offers a $20 gift card reward for participation, and continues to conduct recruitment via mail and telephone. Florida PRAMS has now had three consecutive years of data available (2018, 2019, and 2020) and 2020 data collection met the CDC PRAMS threshold of 55%, which had not been achieved in over 15 years (Florida Health PRAMS, 2021). The PRAMS program continues to update surveillance reports and provide summary reports of specific maternal indicators that are important to Florida, including those relevant to the state health improvement plan, Title V, Tobacco Free Florida, and other efforts. The program has also streamlined its Data Sharing Agreement forms and process.

As PRAMS is preparing to implement the Phase 9 survey in 2023, the Florida PRAMS program and Steering Committee are again reviewing results and recommendations to make further adjustments that may continue to improve response rates, particularly among the priority populations throughout the state.

Limitations of the Evaluation

As this project was conducted in partnership with the state PRAMS program, it was limited to two metropolitan areas and therefore may not represent the views of parents in rural areas or other parts of the state. Furthermore, although a qualitative study does not rely on large numbers but rather aims to achieve depth and quality of key informant perspectives (nor generalizability), the sample size was small (29) for our sampling frame which aimed to reach Black and Hispanic/Latina women in two regions. Thus, additional focus groups, particularly with more Spanish-speaking participants, are needed for future studies. Due to stay-at-home orders imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to conduct additional focus groups within the time frame designated by the state program. Further evaluation with participants from other geographic areas is recommended. Another challenge in implementation of this study was that focus groups interruptions by late arrivals, early departures, and child care needs may have disrupted key contributions or in-depth discussions. Responses could be also be influenced by self-selection bias (those who felt a particular affinity for PRAMS). Furthermore, while any qualitative study is subject to social desirability bias, we took steps to ensure that participants felt comfortable sharing their opinions by creating a friendly and open environment, serving refreshments, and including racially and ethnically diverse facilitators. Further assessment of PRAMS response rates by subgroups (demographics and geography) as well as process stages (mailout versus telephone) would also be informative.

Conclusions for Practice

While more research is needed to make definitive recommendations for improving PRAMS response rates among priority subpopulations, the Black and Latina participants in this assessment shed light on how potential respondents might perceive several aspects of the survey—from the invitation letter, envelope, and reminder cards, to the cover design, to the survey itself. In this evaluation, it was found that most of the participants were not aware of PRAMS but were supportive of maternal child health surveys, were sensitive to the source of the survey, felt that completing the survey via mail was inconvenient, and noted that the survey was too long. Moreover, participants thought the survey design should be more colorful and include pictures of pregnant women and diverse families. Findings highlight the importance of marketing and field-testing of materials—particularly with diverse populations—to increase recognition of PRAMS and improve response rates for similar surveys. Broader dissemination of public health findings from surveys to the general public may increase awareness and appreciation of the value of these efforts among potential respondents.

Furthermore, the results of this evaluation and others support that offering varied methods (i.e., mail, internet/mobile-friendly, telephone, or in-person) of completing the survey should be considered to reduce inconvenience and increase the potential for more frequent data collection in order to use results to make timely improvements to care and support (Ghandour, 2018; Tumin, et al., 2020). The PRAMS survey questions are of great importance to public health, though balancing the number of questions with completion burden on respondents and potential for reduced response rates is a challenge. Findings suggest that limiting the amount of standard, state-added questions (10–30 questions) should be considered to improve survey response rates. Further evaluation of PRAMS materials, methods and content is important for improving response rates and thus ensuring that the PRAMS data are representative and valid, an important resource for public health planning.

Data Availability

Data are not available for public view, however codebook and focus group protocol and questions are available upon request.

References

Binkley, T., Beare, T., Minett, M., Koepp, K., Wey, H., & Specker, B. (2017). Response to an online version of a PRAMS-like survey in South Dakota. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(2), 335–342.

Brick, J. M., & Williams, D. (2013). Explaining rising nonresponse rates in cross-sectional surveys. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645(1), 36–59.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). PRAMS. Retrieved April 04, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Participating PRAMS sites. Retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/prams/prams-data/researchers.htm#data

Cope, D. G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.89-91

Edwards, P., Roberts, I., Clarke, M., DiGuiseppi, C., Pratap, S., Wentz, R., & Kwan, I. (2002). Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: Systematic review. BMJ, 324(7347), 1183.

Florida Health. (2018). Florida Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) 2015 surveillance data book. Retrieved May 14, 2022, from https://www.floridahealth.gov/statistics-and-data/survey-data/pregnancy-risk-assessment-monitoring-system/_documents/reports/prams2015.pdf

Florida Health PRAMS. (2021). Behavioral Survey Data. Retrieved May 15, 2022, from http://www.floridahealth.gov/statistics-and-data/survey-data/pregnancy-risk-assessment-monitoring-system/index.html

Ghandour, R. M. (2018). The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Current strengths and opportunities for growth. American Journal of Public Health, 108(10), 1303.

Gilbert, B. C., Shulman, H. B., Fischer, L. A., & Rogers, M. M. (1999). The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): Methods and 1996 response rates from 11 states. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 3(4), 199–209.

Harrison, S., Henderson, J., Alderdice, F., & Quigley, M. A. (2019). Methods to increase response rates to a population-based maternity survey: A comparison of two pilot studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 65.

Holt, V. L., Martin, D. P., & LoGerfo, J. P. (1997). Correlates and effect of non-response in a postpartum survey of obstetrical care quality. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 150(10), 1117–1122.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2020). Nursing research generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Williams & Wilkins.

Shulman, H. B., D’Angelo, D. V., Harrison, L., Smith, R. A., & Warner, L. (2018). The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): Overview of design and methodology. American Journal of Public Health, 108(10), 1305–1313.

Stedman, R. C., Connelly, N. A., Heberlein, T. A., Decker, D. J., & Allred, S. B. (2019). The end of the (research) world as we know it? Understanding and coping with declining response rates to mail surveys. Society & Natural Resources, 32(10), 1139–1154.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357.

Tumin, R., Johnson, K., Spence, D., & Oza-Frank, R. (2020). The effectiveness of “Push-to-Web” as an option for a survey of new mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(8), 960–965.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jerri Foreman and the Florida PRAMS program, the community partners and organizations who aided the evaluation team in participant recruitment, and the women who volunteered their time to share their perspectives in the focus groups.

Funding

This work was supported by the Florida Department of Health (#B4C95B, USF Project ID#6414110600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed participated in evaluation study design, data collection, analysis, writing, and final approval of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This evaluation study was reviewed by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board and was determined to be exempt.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided verbal consent to participate and were provided a copy of a document explaining informed consent information on the evaluation study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, G., Alastre, S., Vereen, S. et al. Women’s Perspectives on Factors Influencing Florida Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Response. Matern Child Health J 26, 1907–1916 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03472-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03472-9