Abstract

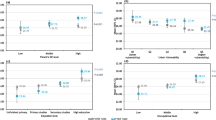

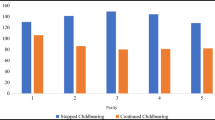

Objective: To investigate the association of socioeconomic position (SEP) with reproductive outcomes among Australian women. Methods: Data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health’s (population-based cohort study) 1973–1978 cohort were used (N = 6899, aged 37–42 years in 2015). The association of SEP (childhood and own, multiple indicators) with age at first birth, birth-to-pregnancy (BTP) intervals and total number of children was analysed using multinomial logistic regression. Results: 14% of women had their first birth aged < 24 years. 29% of multiparous women had a BTP interval within the WHO recommendation (18–27 months). Women with a low SEP had increased odds of a first birth < 24 years: low (OR 7.0: 95% C.I. 5.3, 9.3) or intermediate education (OR 3.8: 2.8, 5.1); living in rural (OR 1.8: 1.5, 2.2) or remote (OR 2.1: 1.7, 2.7) areas; who found it sometimes (OR 1.8: 1.5, 2.2) or always difficult (OR 2.0: 1.6, 2.7) to manage on their income; and did not know their parent’s education (OR 4.5: 3.2, 6.4). Low SEP was associated with having a much longer than recommended BTP interval. Conclusion: As the first Australian study describing social differences in reproductive characteristics, these findings provide a base for reducing social inequalities in reproduction. Assisting adequate BTP spacing is important, particularly for women with existing elevated risks due to social disadvantage; including having a first birth < 24 years of age and a longer than recommended BTP interval. This includes reviewing services/access to postnatal support, free family planning/contraception clinics, and improved family policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aitken, Z., Hewitt, B., Keogh, L., LaMontagne, A. D., Bentley, R., & Kavanagh, A. M. (2016). Young maternal age at first birth and mental health later in life: Does the association vary by birth cohort? Social Science Medicine, 157, 9–17.

Andersson, G., Hoem, J., & Duvander, A. (2006). Social differentials in speed-premium effects in childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 14(4), 51–70.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2007). Recent increases in Australia’s fertility. 4102.0 Australian Social Trends, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2016 from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/0/0FC193CDB42A241BCA25732C00206FBC

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2015). Australia’s mothers and babies 2013–in brief. Perinatal statistics series no. 31. Cat no. PER 72. Retrieved October 10, 2016 from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129553770

Ball, K., Brown, W., & Crawford, D. (2002). Who does not gain weight? Prevalence and predictors of weight maintenance in young women. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorder, 26(12), 1570–1578.

Ball, S., Pereira, G., Jacoby, P., de Klerk, N., & Stanley, F. (2014). Re-evaluation of link between interpregnancy interval and adverse birth outcomes: Retrospective cohort study matching two intervals per mother. BMJ, 349, g4333.

Barber, J. (2001). The intergenerational transmission of age at first birth among married and unmarried men and women. Social Science Research, 30(2), 219–247.

Barclay, K., Keenan, K., Grundy, E., Kolk, M., & Myrskyla, M. (2016). Reproductive history and post-reproductive mortality: A sibling comparison analysis using Swedish register data. Social Science Medicine, 155, 82–92.

Bastian, L., West, N., Corcoran, C., Munger, R., Cache County Study on Memory, Health, & Aging (2005). Number of children and the risk of obesity in older women. Preventive Medicine, 40(1), 99–104.

Bobrow, K., Quigley, M., Green, J., Reeves, G., Beral, V., & Million Women Study Collaborators (2013). Persistent effects of women’s parity and breastfeeding patterns on their body mass index: Results from the Million Women Study. International Journal of Obesity, 37(5), 712–717.

Brown, W., Hockey, R., & Dobson, A. (2010). Effects of having a baby on weight gain. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(2), 163–170.

Conde-Agudelo, A., Rosas-Bermudez, A., & Kaufry-Goeta, A. (2006). Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 295(15), 1809–1823.

Conde-Agudelo, A., Rosas-Bermudez, A., & Kaufry-Goeta, A. (2007). Effects of birth spacing on maternal health: A systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 196(4), 297–308.

Cordero, J. (2009). El espaciamiento de los nacimientos: Una estrategia para conciliar tranajo y familia en Espana (Birth spacing: A strategy for combining work and family in Spain). Revista Espanola de Investigaciones Sociologicas (REIS), 128, 11–33.

Davis, E., Babineau, D., Wang, X., Zyzanski, S., Abrams, B., Bodnar, L., & Horwitz, R. (2013). Short inter-pregnancy intervals, parity, excessive gestational weight gain and risk of maternal obesity. Maternal Child Health, 18(3), 554–562.

de Weger, F., Hukkelhoven, C., Serroyen, J., Te Velde, E., & Smits, L. (2011). Advanced maternal age, short interpregnancy interval, and perinatal outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 204(5), 421.e1–421.e9.

Department of Health, Australia (DoHA). (2009). The Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy 2010–2015. Retrieved October 1, 2016 from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/aust-breastfeeding-strategy-2010-2015.

Gemmill, A., & Lindberg, L. (2013). Short interpregnancy intervals in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 122(1), 64–71.

Gold, R., Connell, F., Heagerty, P., Cummings, P., Bezruchka, S., Davis, R., & Cawthon, M. (2005). Predicting time to subsequent pregnancy. Maternal Child Health Journal, 9(3), 219–228.

Gunderson, E. (2009). Childbearing and obesity in women: Weight before, during and after pregnancy. Obstetrics Gynecology Clinics North America, 36(2), 317–332.

Heffner, J. (2004). Advanced maternal age: How old is too old? New England Journal of Medicine, 351(19), 1927–1929.

Hilder, L., Zhichao, Z., Parker, M., Jahan, S., & Chambers, G. (2014). Australia’s mothers and babies 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2016 from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129550033.

Huber, S., Bookstein, F., & Fieder, M. (2010). Socioeconomic status, education, and reproduction in modern women: An evolutionary perspective. American Journal of Human Biology, 22(5), 578–587.

Kaharuza, F., Sabroe, S., & Basso, O. (2001). Choice and chance: Determinants of short interpregnancy intervals in Denmark. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 80(6), 532–538.

Lahmann, P., Lissner, L., Gullberg, B., & Berglund, G. (2000). Sociodemographic factors associated with long-term weight gain, current body fatness and central adiposity in Swedish women. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorder, 24(6), 685–694.

Lee, C., Dobson, A., Brown, W., Bryson, L., Byles, J., Warner-Smith, P., & Young, A. (2005). Cohort profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(5), 987–991.

Lee, C., & Gramotnev, H. (2006). Predictors and outcomes of early motehrhood in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Psychology Health Medicine, 11(1), 29–47.

Marston, C. (2005). Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing. Retrieved October 1, 2016 from http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/birth_spacing05/en/.

McMahon, C., Boivin, J., Gibson, F., Hammarberg, K., Wynter, K., Saunders, D., & Fisher, J. (2011). Age at first birth, mode of conception and psychological wellbeing in pregnancy: Findings from the parental age and transition to parenthood Australia (PATPA) study. Human Reproduction, 26(6), 1389–1398.

Merrill, R., Fugal, S., Novilla, L., & Raphael, M. (2005). Cancer risk associated with early and late maternal age at first birth. Gynecologic Oncology, 96(3), 583–593.

Miranti, R., McNamara, J., Tanton, R., & Yap, M. (2009). A narrowing gap? Trends in the childlessness of professional women in Australian 1986–2006. Journal of Population Research, 26, 359–379.

Mirowsky, J. (2005). Age at first birth, health and mortality. Journal of Health Social Behavior, 46(1), 32–50.

Nabukera, S., Wingate, M., Salihu, H., Owen, J., Swaminathan, S., Alexander, G., & Kirby, R. (2009). Pregnancy spacing among women delaying initiation of childbearing. Archives Gynecology Obstetrics, 279(5), 677–684.

Pink, B. (2013). Technical paper: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. (2033.0.55.001). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics Retrieved October 1, 2016 from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2033.0.55.001.

Pirkle, C., de Albuquerque Sousa, A., Alvarado, B., Zunzunequi, M., & IMIAS Research Group (2014). Early maternal age at first birth is associated with chronic diseases and poor physical performance in older age: Cross-sectional analysis from the International Mobility in Aging Study. BMC Public Health, 14, 293.

Restrepo-Mendez, M. C., Lawlor, D. A., Horta, B. L., Matijasevich, A., Santos, I. S., Menezes, A. M., Barros, F. C., & Victora, C. G. (2015). The association of maternal age with birthweight and gestational age: A cross-cohort comparison. Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiology, 29(1), 31–40.

Smith, G., Pell, J., & Dobbie, R. (2003). Interpregnancy interval and risk of preterm birth and neonatal death: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ, 327(7410), 313.

Ventura, S. J., Martin, J. A., Curtin, S. C., & Mathews, T. J. (1998). Report of final natality statistics, 1996. Monthly Vital Statistics Report, 46(11 Suppl), 1–99.

Wamala, S., Wolk, A., & Orth-Gomer, K. (1997). Determinants of obesity in relation to socioeconomic status among middle-aged Swedish women. Preventive Medicine, 26, 734–744.

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2013). BMI classification. Global Database on Body Mass Index. Retrieved October 10 2016, from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided the survey data. N.H. is supported by the Australian Postgraduate Award scholarship and G.D.M. is supported by the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT120100812). IK is supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (project 2006-1518). The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holowko, N., Jones, M., Tooth, L. et al. Socioeconomic Position and Reproduction: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Matern Child Health J 22, 1713–1724 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2567-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2567-1