Abstract

We conduct a comparative analysis of breastfeeding behavior between military and civilian-affiliated mothers. Our focus is on African American mothers among whom breastfeeding rates are lowest. The military context may mitigate conditions associated with low breastfeeding prevalence by (a) providing stable employment and educational opportunities to populations who face an otherwise poor labor market and (b) providing universal healthcare that includes breastfeeding consultation. Using pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS) data for which we received special permission from each state to flag military affiliation, we analyze civilians and military affiliate in breastfeeding initiation using logistic regression and breastfeeding duration using Cox proportional hazard analysis. We find that breastfeeding is more prevalent among all women in the military setting and that the black–white gap in breastfeeding duration common among civilians is significantly reduced among military affiliates. Breastfeeding is a crucial component of maternal and child health and eliminating racial disparities in its prevalence is a public health priority. This study is the first to identify the military as an important institutional context that deserves closer examination to glean potential policy implications for civilian society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We were unable to identify whether women still had military insurance as of the survey date using the well baby care insurance variable because it was not included in phase 5 and had substantial missing values in phases 3 and 4. We were, however, able to determine the opposite scenario, where women had military insurance for their prenatal care but were no longer affiliated with the military at birth. This affected 279 women. In separate analyses using a dummy for previous military affiliation, we found no significant relationship to the breastfeeding outcomes analyzed in this paper.

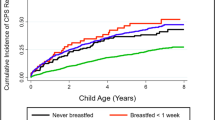

Each 4-, 8-, and 16-week period measurement in the figure excludes individuals for whom no data was available because they received the survey before their infant was that old. In the multivariate analyses we account for these individuals using right censorship.

A larger percentage of Asians in the military are Filipino compared to in the civilian population [28] and this is also the case in our data. While we can only speculate, recent research has shown that infant formula lobbying in the Philippines has been linked to lowered breastfeeding rates among Filipino women [29].

References

American Academy of Pediatrics Section of Breastfeeding. (2012). Policy statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129, e827–e841.

Guttman, N., & Zimmerman, D. R. (2000). Low-income mothers’ views on breastfeeding. Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1457–1473.

Ryan, A. S., Zhou, W., & Acosta, A. (2002). Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium. Pediatrics, 110, 1103–1109.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2007). The association of couples’ relationship status and quality with breastfeeding initiation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1107–1117.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Progress in increasing breastfeeding and reducing racial/ethnic differences: United States, 2000–2008 births. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 77–90.

Belanoff, C. M., McManus, B. M., Carle, A. C., McCormick, M. C., & Subramanian, S. V. (2012). Racial/ethnic variation in breastfeeding across the US: A multilevel analysis from the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2007. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 14–26.

Centers for Disease Control. (2006). Racial and socioeconomic disparities in breastfeeding—United States, 2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55, 335–339.

Li, R., & Grummer, S. L. (2002). Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding among United States infants: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Birth, 29, 251–257.

Forste, R., Weiss, J., & Lippincott, E. (2001). The decision to breastfeed in the United States: Does race matter?. Pediatrics, 108, 291–296.

Kurinij, N., Shiono, P. H., & Rhoads, G. G. (1988). Breastfeeding incidence and duration in black and white women. Pediatrics, 81, 365–371.

Williams, D. R. (2012). Miles to go before we sleep: Racial inequities in health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 279–295.

Healthy People. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/DisparitiesAbout.aspx.

Lee, H. J., et al. (2009). Racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration among low-income inner-city mothers. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 1251–1271.

Mao, C., Narang, S., & Lopreiato, J. (2012). Breastfeeding practices in military families: A 12-month prospective population-based study in the national capital region. Military Medicine, 177, 229–234.

Bell, M. R., & Ritchie, E. C. (2003). Breastfeeding in the military: Part I. Information and resources provided to service women. Military Medicine, 168, 807–812.

Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC). (2011). Population representation in the military services. http://prhome.defense.gov/rfm/MPP/ACCESSION%20POLICY/PopRep2011/download/download.html. Accessed September 26, 2012.

Lundquist, J. H. (2008). Reevaluating ethnic and gender satisfaction differences: The effect of a meritocratic institution. American Sociological Review, 73, 477–496.

Lundquist, J. H., & Smith, H. (2005). Family formation in the U.S. military: Evidence from the NLSY. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 67, 1–13.

Lundquist, J. H. (2004). When race makes no difference: Marriage and the military. Social Forces, 83(2), 1–28.

Lundquist, J. H., & Xu, Z. (2014). Reinstitutionalizing families: Lifecourse policy and marriage in the military. Journal of Marriage and the Family (Conditional Acceptance).

Buckler, A. G. (2011). The military health system and TRICARE: Breastfeeding promotion. Breastfeeding Medicine, 6, 295–297.

Haas, D. M., et al. (2006). Assessment of breastfeeding practices and reasons for success in a military community hospital. Journal of Human Lactation, 22, 439–445.

Bales, K., Washburn, J., & Bales, J. (2012). Breastfeeding rates and factors related to cessation in a military population. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7, 436–441.

Sleutel, M. R. (2012). Breastfeeding during military deployment. Nursing for Women’s Health, 16, 20–25.

Office of the Deputy under Secretary of Defense. (2005). Demographics report. http://cs.mhf.dod.mil/content/dav/mhf/qol-library/pdf/mhf/qol-resources/reports/2005demographicsreport.pdf.

Office of the Surgeon General (US). (2011). The surgeon general’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General The Importance of Breastfeeding. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK52687/.

Centers for Disease Control. (2007). National Immunization Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services.

Stewart, C. (2011). Veterans’ racial and ethnic composition and place of birth. Washington DC: US Census Bureau Publications-Population.

Sobel, H. L., Iellamo, A., Raya, R. R., Padilla, A. A., Olivé, J. M., & Nyunt-U, S. (2011). Is unimpeded marketing for breast milk substitutes responsible for the decline in breastfeeding in the Philippines? An exploratory survey and focus group analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 73(10), 1445–1448.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge grant funding from NSF (SES-0751505). Jennifer Lundquist is the PI on this grant. We would like to thank Jessica Looze for her contribution to this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lundquist, J., Xu, Z., Barfield, W. et al. Do Black–White Racial Disparities in Breastfeeding Persist in the Military Community?. Matern Child Health J 19, 419–427 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1524-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1524-x