Abstract

Schlenker (Semant Pragmat 2(3):1–78, 2009; Philos Stud 151(1):115–142, 2010a; Mind 119(474):377–391, 2010b) provides an algorithm for deriving the presupposition projection properties of an expression from that expression’s classical semantics. In this paper, we consider the predictions of Schlenker’s algorithm as applied to attitude verbs. More specifically, we compare Schlenker’s theory with a prominent view which maintains that attitudes exhibit belief projection, so that presupposition triggers in their scope imply that the attitude holder believes the presupposition (Karttunen in Theor Linguist 34(1):181, 1974; Heim in J Semant 9(3):183–221, 1992; Sudo in The art and craft of semantics: a festschrift for Irene Heim, MIT Press, 2014). We show that Schlenker’s theory does not predict belief projection, and discuss several consequences of this result.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to a prominent view of presuppositions, attitude verbs exhibit belief projection.Footnote 1 That is: presupposition triggers in the attitude’s scope imply that the subject believes the presupposition. For example, consider:

Bill stopped smoking presupposes that Bill used to smoke. Consequently, proponents of belief projection maintain that each report presupposes that Ann believes that Bill used to smoke. Theorists cite several kinds of evidence for belief projection. First, the belief entailment persists in embedded environments, which is diagnostic of presuppositions (Chierchia and McConnell-Ginet, 2000):

Second, the presupposition triggered by the attitude can be filtered by the subject’s beliefs. For instance, (3) presupposes nothing.

Third, denying the relevant beliefs results in infelicity:

The data in (2)–(4) are all explained by belief projection.

This paper is about the relationship between belief projection and the influential theory of presupposition projection from Schlenker (2009, 2010a, b). Schlenker’s account is a version of the satisfaction theory of presuppositions, which says that every presupposition must be entailed by the local context of its trigger, or must be “locally satisfied”.Footnote 2 Schlenker’s proposal is distinguished by a novel algorithm for computing the local context of each expression in a sentence from its truth conditional meaning. Roughly speaking, on this approach the local context of an expression in a sentence is the strongest piece of information that can be conjoined to that expression without affecting whether the sentence is true or false at any world in the context.

We show that Schlenker’s theory does not predict belief projection for verbs of desire such as ‘want’, ‘hope’, and ‘wish’, or fictives such as ‘imagine’ and ‘dream’. Instead, his theory predicts that when a presupposition trigger is embedded under an attitude, the sentence presupposes that the agent bears that same attitude to the presupposition. Thus, on Schlenker’s account the local context for the attitude is not the agent’s beliefs, but rather is the agent’s desires, imaginings, or dreams, as the case may be.

To be clear, our aims here are relatively modest. Our primary goal is to make explicit the predictions of Schlenker’s algorithm, and contrast them with belief projection. Although we will briefly consider the relative advantages of each theory, we will not be arguing for one account over another. Still, we hope that our discussion will help to clarify and focus the debate, and highlight some of the difficulties and outstanding problems in this fascinating area of semantic research.

Before we begin, it is worth remarking that our discussion touches on two recent strands of the literature on presuppositions. First, some of our arguments involving attitudes build on analogous results about conditionals from Mandelkern and Romoli (2017) and Mackay (2019). These authors maintain that Schlenker’s local context algorithm makes incorrect predictions for a range of conditional constructions. However, there are also significant differences between our conclusions and theirs. For instance, Mackay (2019) argues that his result can be avoided by modifying the semantics for conditionals. By contrast, we show there is no natural treatment of all verbs of desire and fictives that generates belief projection when combined with Schlenker’s algorithm.

Second, our arguments impact a widely discussed issue concerning whether it is legitimate to simply stipulate local contexts on a case by case basis, as a matter of the lexical semantics of various expressions, or whether the local context of an expression must follow from a more general theory.Footnote 3 Schlenker (2009, 2010a, b) is perhaps the most sophisticated attempt to develop a general, systematic account of local contexts. However, Schlenker (2020) and Anvari and Blumberg (2021) have argued that Schlenker’s (2009) algorithm makes incorrect predictions for nominal modifiers and quantificational determiners. Consequently, Anvari and Blumberg (2021) suggest that the local contexts of these expressions might have to be stipulated. Similarly, we argue that if belief projection is ultimately correct, then the local context of attitude verbs will also need to be stipulated.Footnote 4

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 summarizes Schlenker’s theory of presupposition projection. Section 3 shows that the theory does not predict belief projection given a quantificational semantics for verbs of desire and fictives. Section 4 considers incorporating presuppositions involving the subject’s beliefs into these semantics. Section 5 extends the results beyond quantificational approaches. Section 6 briefly explores the prospects of abandoning belief projection. Section 7 concludes by considering how our results could impact the debate around the so-called “explanatory problem” for dynamic semantics.

2 Presupposition and local context

This section summarizes Schlenker’s (2009, 2010b) theory of presupposition projection. His account is a version of the satisfaction theory, which says that every presupposition must be entailed by the local context of its trigger, or must be “locally satisfied”.Footnote 5 The local context of an expression \(\textsf {E}\) aggregates information contributed by the common ground, together with the meaning of particular expressions in \(\textsf {E}\)’s syntactic environment. To illustrate, consider:

The second conjunct of (5) presupposes that Bill used to smoke. But (5) presupposes nothing. To explain this, many have claimed that the local context of \(\textsf {q}\) in \(\textsf {p}\,\textsf { and }\, \textsf {q}\) is the combination of the common ground and \(\textsf {p}\). This guarantees that the presupposition of stopped in (5) is satisfied in its local context, regardless of what information is in the common ground.

To make predictions about projection, Schlenker develops an algorithm for computing local contexts. The local context of an expression in a sentence is, roughly, the strongest information that can be conjoined to that expression without affecting whether the sentence is true or false at any world in the context. More precisely, Schlenker’s algorithm defines the local context of expression \({\textsf {E}}\) in a syntactic environment \({\textsf {a\_b}}\) and global context C. The local context is the strongest proposition (or ‘restriction’) that can be added to anything in \({\textsf {E}}\)’s syntactic position without affecting whether the resulting sentence is true or false in C. The algorithm is incremental, allowing replacement of \({\textsf {b}}\) with any other “good final” \({\textsf {b'}}\) where \({\textsf {aEb'}}\) is grammatical.Footnote 6 Say that sentences \({\textsf {s}}\) and \({\textsf {s'}}\) are equivalent in C (\({\textsf {s}}\leftrightarrow _{\textit{C}}\, {\textsf {s}}'\)) iff \({\textsf {s}}\) and \({\textsf {s'}}\) have the same truth value at every world in C. Then:

To illustrate, return to (5). Schlenker’s algorithm predicts that the local context of the second conjunct in (5) is the combination of the global context C and the worlds where the first conjunct (used) is true (call this set used). To see why, consider \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = C \cap \, {\textbf {used}}\). First, for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (7-a) and (7-b) are equivalent in C:

Second, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) is the strongest restriction that creates contextual equivalence. To see why, consider a stronger restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world \(w \in C\) in which Bill used to smoke. Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Then contextual equivalence fails, because (8-a) is false and (8-b) is true at w:

So, according to Schlenker’s algorithm, \(C \cap {\textbf {used}}\) is the local context of the second conjunct in (5).

In the next section we show that Schlenker’s theory does not predict belief projection in verbs of desire and fictives.

3 Attitude verbs’ local context

Since Hintikka (1962), many have analyzed attitude verbs as quantifiers over possible worlds. We argue that Schlenker’s theory does not predict belief projection when combined with a first pass version of these quantification theories.

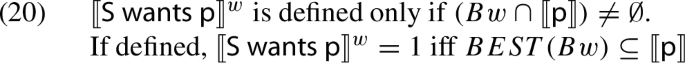

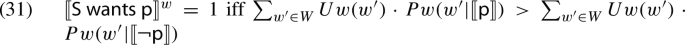

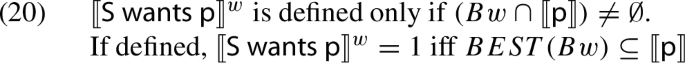

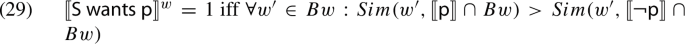

On a popular semantics for want, this verb universally quantifies over the most desirable worlds consistent with what the agent believes.Footnote 8 More precisely, let Bw be the worlds consistent with what the agent believes at w. Let BEST be a preference function that maps a set of worlds A to the subset of most desirable worlds in A.Footnote 9

For example, Ann wants to smoke is true just in case all of Ann’s most preferred belief worlds are worlds where she smokes.

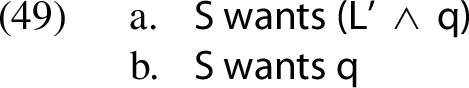

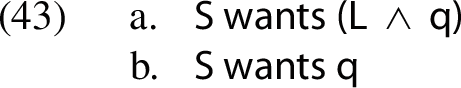

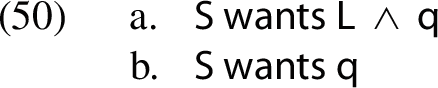

Now consider the result of applying Schlenker’s algorithm to (9). The local context for \({\textsf {p}}\) in \({\textsf {S wants p}}\) is the strongest information \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) that can be conjoined to any claim \({\textsf {q}}\) while guaranteeing that \({\textsf {S wants L}}\, \wedge \, {\textsf {q}}\) is contextually equivalent to \({\textsf {S wants q}}\). Applying Schlenker’s algorithm, this local context is the union, for any world w in the global context C, of the most preferred belief worlds at w, BEST(Bw).

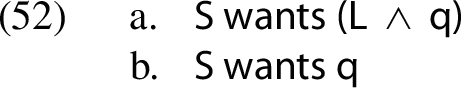

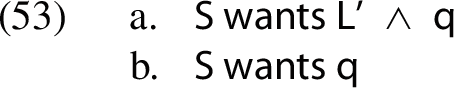

To see why, let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = \bigcup \left\{ BEST(Bw) \mid w \in C\right\} \). First, for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (11-a) and (11-b) are equivalent in C:

Second, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) is the strongest restriction that creates contextual equivalence. To see why, consider a stronger restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world \(v \in BEST(Bw)\) for some \(w \in C\). Then contextual equivalence fails, because (12-a) is false and (12-b) is true at w, where \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = BEST(Bw)\).

So, Schlenker’s algorithm predicts that \(\bigcup \left\{ BEST(Bw) \mid w \in C\right\} \) is the local context of the complement of want.

This local context fails to predict belief projection. (1-b) would imply (13-a) rather than (13-b), because the presupposition of stopped would need to be satisfied by Ann’s most preferred belief worlds, rather than by all of Ann’s belief worlds.

In order to derive belief projection, the required local context would need to be \(\bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \), which is the agent’s belief worlds at any world in the global context.

Now turn from verbs of desire to fictives such as imagine. On a popular approach, fictives have a quantificational semantics involving quantification over a set of worlds that is possibly disjoint from the agent’s beliefs.Footnote 10 Where Iw represents the worlds consistent with what the relevant agent imagines (again suppressing agent relativity):

For example, Ann imagines that Bill used to smoke is true just in case all of the worlds consistent with what Ann is imagining are worlds where Bill used to smoke.

Now consider the result of applying Schlenker’s algorithm to (9). By parity of reasoning from the case of want, we have:

The key fact here is that the set of worlds consistent with what the agent imagines is the strongest information that can be added to the complement of an imagination report without affecting truth values.

Again, this local context fails to predict belief projection. (1-b) would imply (13-a) rather than (13-b), because the presupposition of stopped would need to be satisfied by Ann’s imagination worlds, rather than by Ann’s belief worlds.Footnote 11

The results generalize beyond these examples. Quantificational attitude verbs are a type of Kratzerian modal. On the Kratzerian analysis, modals quantify over a domain of possibilities. This domain is fixed by two parameters: (i) the modal base f, which supplies a set of possibilities \(\cap f(w)\), and (ii) the ordering source g, which determines the highest-ranked members of that set, \(BEST(g(w), \cap f(w))\).Footnote 12 Where \(\textsf {M}\) is a modal, and \(Q_{\textsf {M}}\) is a generalized quantifier associated with \(\textsf {M}\):

For instance, \({\textsf {must p}}\) is true just in case \(\textsf {p}\) is true at all of the top-ranked worlds, and \({\textsf {may p}}\) is true just in case \(\textsf {p}\) is true at some of the top-ranked worlds. Different modal flavors (epistemic, deliberative, deontic, bouletic, circumstantial) correspond to different choices of modal base and ordering source (see Kratzer, 1977, 1981, 1991, 2012).

Likewise with attitude verbs. Fictives like imagine have an empty ordering source, so that every world in the modal base is among the best worlds in the modal base. Verbs of desire have an ordering source that reflects the agent’s preferences, and differ regarding the choice of modal base. In the case of want, the modal base is the agent’s beliefs. These choices of ordering sources and modal base recover the earlier meanings for want and imagine as special cases.

The general result is that Schlenker’s theory predicts that the local context for the prejacent of a Kratzerian modal is not the modal base, but rather is the set of best worlds in the modal base:Footnote 13

The next section considers whether belief projection can be captured by enriching the quantificational theory with doxastic presuppositions. Then Sect. 5 considers whether belief projection can be captured by theories of attitudes that depart altogether from the quantificational framework.

4 Doxastic presuppositions

Section 3 treated want as a universal quantifier over the agent’s most preferred belief worlds. But some theorists think that this is too simplistic. They argue that want also contributes a further presupposition, requiring that its complement is consistent with the agent’s beliefs.Footnote 14 In the setting of the quantificational semantics above, this produces the following meaning:

Combined with Schlenker’s algorithm, this revised entry accounts for belief projection.Footnote 15

The key idea is that since the complement must be consistent with the agent’s beliefs, contextual equivalence is only guaranteed when all of the agent’s belief worlds are included in the local context.

However, we don’t think that appealing to doxastic presuppositions provides a compelling strategy to derive belief projection. First, several theorists have expressed skepticism that wants even has a compatibility requirement. For example, in recent work Grano and Phillips-Brown (2021) point to “counterfactual want ascriptions” such as:

Footnote 16 Such examples are felicitous, but would not be if want reports carried a belief constraint.

Second, the purported compatibility requirement doesn’t project like a presupposition.Footnote 17 After all, none of (23-a)–(23-c) suggest that Ann’s belief state leaves open whether Bill passed his test:

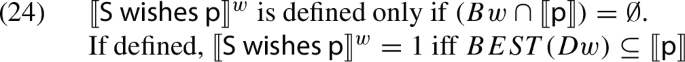

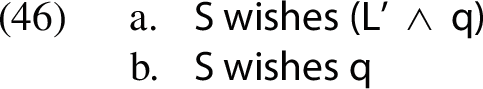

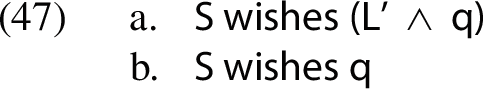

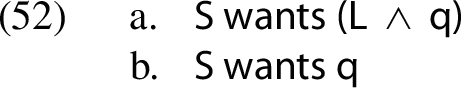

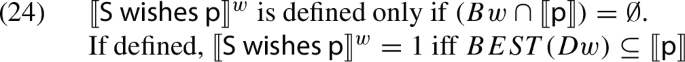

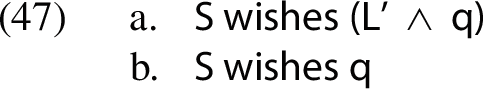

Finally, appealing to doxastic presuppositions does not explain belief projection in the full range of attitude verbs. Several theorists have argued that wish is counterfactual, presupposing that its complement is incompatible with the agent’s beliefs.Footnote 18 When defined, \({\textsf {S wishes p}}\) is true only if \({\textsf {p}}\) is true throughout the most preferred worlds in some domain Dw.

The precise identity of Dw, plausibly some superset of the agent’s belief worlds, is not relevant for our purposes. However, it is important that the most preferred worlds in Dw are not belief worlds, i.e. \(BEST(Dw) \cap Bw = \emptyset \). Consequently, the counterfactual presupposition derives a local context that is a strict superset of the subject’s belief set.Footnote 19

This local context predicts that Ann wishes Bill would stop smoking implies not only that Ann believes Bill used to smoke, but also that Ann wishes Bill used to smoke. Note that although this explains some of the data motivating belief projection, it doesn’t capture all of it. For instance, consider the belief filtering effect in (26):

Intuitively, (26) presupposes nothing. However, given the above local context for the complement of ‘wish’, it can be shown that (26) is instead predicted to carry a non-trivial presupposition (roughly equivalent to If Ann thinks that Bill used to smoke, then she wishes he used to smoke).Footnote 20

Moreover, belief projection occurs not only in verbs of desire, but also in fictives like imagines, dreams, and supposes. But fictives do not constrain the subject’s beliefs. People can imagine things that are compatible with, entailed by, or contradicted by their beliefs. We see little hope of deriving belief projection for these attitudes by appealing to such constraints.Footnote 21

5 Beyond quantification

Another attempt to derive belief projection replaces the quantificational analysis with a different kind of semantics for attitudes.

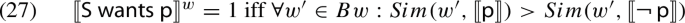

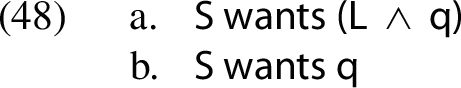

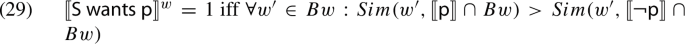

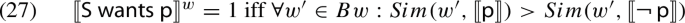

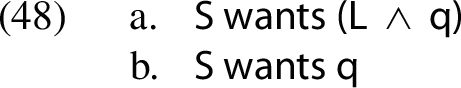

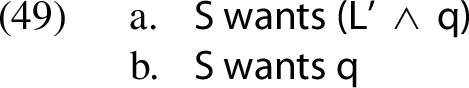

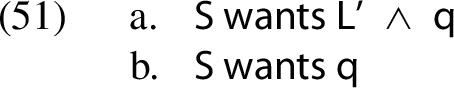

When it comes to desire verbs, there are two alternatives to the quantificational treatment. One approach builds on Stalnaker (1984), and substitutes quantification with comparative desirability. The basic idea is that S desires p when S prefers the closest p-worlds to the closest \(\lnot p\)-worlds. Perhaps the simplest comparative analysis goes as follows, where Sim(w, p) is the set of closest p-worlds to w and > is a preference relation over propositions.

However, this account predicts that the local context for the complement of want should be the set of all worlds, W. This essentially means that want reports should carry no presuppositions at all, which is clearly incorrect.Footnote 22

The key fact here is that each complement requires consideration of a different set of closest worlds, and so no particular candidate local context can be held fixed to guarantee contextual equivalence.

However, more sophisticated comparative analyses have been proposed. For instance, rather than considering the closest worlds outright, Heim (1992) instead proposes that we examine the closest belief worlds where the complement and its negation hold.

This semantics delivers belief projection.Footnote 23

In this way, the status of belief projection turns on whether the comparative semantics itself is sensitive in the right way to the agent’s beliefs.Footnote 24

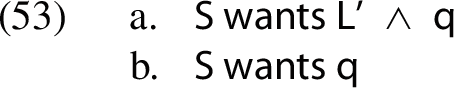

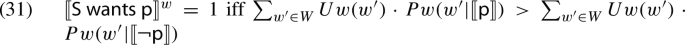

The second alternative approach to verbs of desire models these expressions in terms of expected value. Suppose the subject’s credence function at w, Pw, assign a positive probability to all and only worlds in Bw. Let the subject’s utility function at w, Uw, assign a value to all worlds. Then on this analysis the agent wants whatever has greater expected value than its negation (here > denotes the natural ordering over real numbers):Footnote 25

This semantics delivers belief projection:Footnote 26

This result is less interesting than the corresponding result for the comparative desirability semantics in (29). This is because the expected value concept in (31) is defined in terms of conditionalizing the subject’s credence function. But on standard approaches to conditionalization, \(Pw(w'|\llbracket \textsf {p}\rrbracket )\) will be undefined if the subject believes \(\lnot p\), and \(Pw(w'|\llbracket \lnot {\textsf {p}}\rrbracket )\) will be undefined if the subject believes p. So, the expected value semantics independently induces the kind of compatibility presupposition we discussed in Sect. 4. Consequently, it is not surprising that this entry derives belief projection.

Although the semantics in (29) and (31) derive belief projection on Schlenker’s algorithm, it is worth pointing out that adopting alternative analyses won’t derive belief projection for desire verbs in general. For instance, since what a subject wishes can be incompatible with what they believe, on a comparative desirability account of wish it would be inappropriate to constrain the similarity calculation by intersecting with the subject’s beliefs, as in (29). Indeed, ignoring presuppositions, Heim’s (1992) semantics for wish is essentially the entry in (27). But as we have seen, that entry fails to derive belief projection.Footnote 27

Turning finally to fictives, we will be fairly brief since we aren’t aware of any serious alternatives to a quantificational analysis of these expressions. Attitudes such as imagining, dreaming and supposing do not involve any obvious comparative aspect, and it seems implausible that their analysis is tied to decision-theoretic concepts. So, entries modeled on (29) and (31) would be inappropriate for these attitudes. More generally, the prospects for deriving belief projection for fictives by appealing to alternative analyses appear fairly dim.Footnote 28\(^{,}\)Footnote 29

6 Rejecting belief projection

In this section, we briefly consider the prospects of rejecting belief projection, and survey possible strategies for explaining some of the data supporting it by other means.

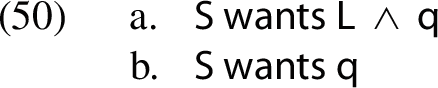

First, we saw in Sect. 1 that beliefs filter the attitude presuppositions, which is exactly what belief projection would predict. In particular, the following sentences have no presuppositions:

However, as several theorists have observed, the same filtering occurs with want/want and imagine/imagine constructions:

These patterns are not predicted on belief projection. Instead, given belief projection an example such as (34-a) is predicted to carry a non-trivial presupposition (roughly equivalent to the conditional If Bill wants to own a cello, then he believes that he owns a cello). Defenders of belief projection have tried to account for these examples by appealing to modal subordination.Footnote 30 Roughly speaking, this is the phenomenon whereby possibilities raised to salience by earlier discourse shape the intensional environments relevant for the evaluation of later discourse. For example, (35) presupposes nothing, which is not predicted on standard accounts of the way presuppositions project from conditionals:

The idea is that the antecedent of the first conjunct in (35) raises to salience possibilities in which Bill comes to the party. And it is these possibilities against which the second conjunct is evaluated, which explains why the presupposition triggered by Mary comes too is satisfied. Similarly, the thought is that in conjunctions such as (34-a), the first conjunct raises to salience Bill’s most highly preferred belief worlds, and it is only those possibilities that are relevant for satisfying the presupposition triggered by the second conjunct.

For proponents of Schlenker’s algorithm, the dialectic with respect to (33) and (34) is reversed: Schlenker’s account incorrectly predicts that the examples in (33) should trigger non-trivial presuppositions (in the case of (33-b), for instance, the presupposition would be roughly equivalent to the conditional If Bill thinks that Ann used to smoke, then he is imagining that she used to smoke), but it correctly predicts that the examples in (34) should be presuppositionless.

In response, proponents of Schlenker’s theory could try to appeal to modal subordination in order to explain belief filtering. For instance, the idea is that the first conjunct in (33-a)/(33-b) raises to salience Bill’s belief worlds, and it is exactly those possibilities that are relevant for satisfying the presupposition triggered by ‘stop smoking’ in the second conjunct. Although modal subordination has not been applied in quite this way before, as far as we can see there is nothing conceptually incoherent about this response. We suspect that its ultimate tenability will rest on fairly fine-grained details in the final theory of modal subordination, and for those who endorse Schlenker’s theory we think that this could be an intriguing place for further research. Overall, then, when it comes to the belief-filtering data, proponents of Schlenker’s system are not at an obvious disadvantage compared to those who endorse belief projection.Footnote 31

Second, we remarked in Sect. 1 that examples such as those in (36) give rise to a belief entailment; they all suggest that Ann believes Bill used to smoke.

A reviewer suggests that proponents of Schlenker’s algorithm could derive this effect as follows. First, assume the first-run quantificational entry for ‘want’ from Sect. 3 (\(\llbracket {\textsf {S wants p}}\rrbracket ^{w} = 1\) iff \(BEST(Bw) \subseteq \llbracket \textsf {p}\rrbracket \)). Then Schlenker’s algorithm predicts that the sentences in (36) should all carry a presupposition that is too weak, namely that only Ann’s best belief worlds are ones where Bill used to smoke. However, it is known that presuppositions are strengthened in certain situations. For example, consider (37):

According to the standard satisfaction theory, (37) triggers a conditional presupposition to the effect that if Ann mowed the lawn, then she has a wife. But in fact (37) implies the unconditional claim that Ann has a wife. Somehow the conditional presupposition gets strengthened.Footnote 32 The thought is that this strengthening mechanism is also at play in (36), converting the relatively weak presupposition predicted by Schlenker’s theory into the required belief entailment.

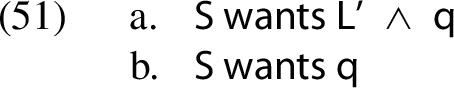

We think that this is an interesting response that deserves a more thorough discussion than we can undertake here. That said, we want to bring out two features of this package that could help to guide further research. For one thing, it is worth noting that Schlenker’s account in conjunction with strengthening doesn’t yield exactly the same predictions as belief projection. In some cases, the predictions are strictly stronger than those delivered by belief projection. For instance, consider fictives such as ‘imagine’:

Assuming the quantificational entry for ‘imagine’ from Sect. 3 (\(\llbracket {\textsf {S imagines p}}\rrbracket ^{w} = 1\) iff \(Iw \subseteq \llbracket \textsf {p}\rrbracket \)), Schlenker’s algorithm predicts that the examples in (38) should carry the following presupposition: all of Ann’s imagination worlds are ones where Bill used to smoke. If we then apply the strengthening mechanism we have that, for example, (38-a) presupposes that all of Ann’s imagination worlds and all of Ann’s belief worlds are ones where Bill used to smoke. This presupposition is strictly stronger than that predicted by belief projection. One area for future work could try to use these divergent predictions to try to tease apart these two accounts empirically.Footnote 33\(^{,}\)Footnote 34

Finally, we observe that the strengthening mechanism appears to be obligatory. Consider the following examples:

These sentences sound incoherent; denying the belief entailment in an attitude report produces absurdity. This is just what belief projection predicts. By contrast, it appears that Schlenker’s theory can only make sense of the infelicity here if the operation of strengthening is obligatory. If this is correct, then the plausibility of Schlenker’s approach will partly turn on the tenability of mandatory presupposition strengthening.Footnote 35

In general, the data points considered here appear to be more easily explicable on a theory which validates belief projection compared to Schlenker’s approach.Footnote 36\(^{,}\)Footnote 37 However, there are still several avenues available to proponents of Schlenker’s algorithm in dealing with this data, and we have tried to outline those that seem most promising.

7 Conclusion

We’ll close by revisiting the “explanatory problem” for dynamic semantics briefly discussed in Sect. 1. This debate is between those who stipulate projection properties as a matter of lexical semantics, and those who derive them from truth conditional meaning. Dynamic theories like Heim (1983, 1992) stipulate context change potentials for connectives and attitude verbs. However, some have objected to this framework on the grounds that it is insufficiently explanatory (Heim, 1990; Schlenker, 2009; Soames, 1982). This prompted Schlenker (2009) to offer an algorithm for deriving local contexts from truth conditional meanings.

Let us suppose that belief projection does in fact capture the behavior of attitude reports, and that Schlenker’s algorithm issues the wrong local contexts for attitude verbs. Then it is not obvious how to derive the local context for attitudes from their truth conditional meaning. As we have seen, this is perhaps most forceful in the case of fictives, such as imagine and dream. For instance, it is difficult to see how any theory could derive belief projection from the truth conditional meaning of imagine. Instead, from the perspective of the at-issue meaning of this verb, projection seems to be an arbitrary fact, and requires semantic stipulation.

If this is correct, then the “explanatory challenge” starts to look less urgent for dynamic semantics. Taken to its principled conclusion, this challenge requires that we provide a general, non-stipulative theory that can predict the appropriate local context for each expression, including those in the scope of attitude verbs. But if no such general account can be provided, because the local contexts of attitudes need to be stipulated in order to capture belief projection, then the explanatory challenge loses its bite. For if every account needs to stipulate the local contexts of certain expressions, then the differences between purportedly explanatory theories and stipulative accounts become less distinct.Footnote 38\(^{,}\)Footnote 39

Notes

We will expand on this point in Sect. 7.

Another influential approach to presuppositions is the binding theory, on which presuppositions are parts of the logical form of a sentence that can be anaphoric on other parts. See van der Sandt (1992), Geurts (1999) and Maier (2009, 2015) for discussion, among many others. For recent criticism of the binding theory’s treatment of attitudes, see Blumberg (2022).

Schlenker also defines a symmetric version of the algorithm, which could play the same role in our discussion throughout.

Our presentation of Schlenker’s algorithm follows Mandelkern and Romoli (2017).

Strictly speaking, both Bw and BEST are relativized to the agent, and BEST is relativized to the world of evaluation; but this is suppressed for simplicity.

See for example Percus and Sauerland (2003), Anand (2007), Yalcin (2007), Stephenson (2010) and Berto (2018) among others. More explicitly, we assume (i) that fictives are representational attitude verbs, like ‘believe’, whose semantics triggers quantification over a range of possibilities; and (ii) that fictive reports do not require that the prejacent is compatible with the subject’s beliefs. As far as we know, every existing analysis of fictives conforms to both (i) and (ii). Thus, our results about fictives are fairly general, and don’t hang on any particular semantics for these verbs.

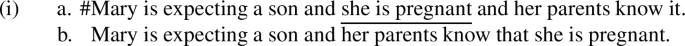

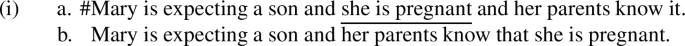

In Schlenker (2008), develops a precursor to the theory of local contexts presented in Schlenker (2009, 2010a, b). The account in Schlenker (2008) tries to derive presupposition projection facts from judgments about semantic redundancy. For instance, the infelicity of (i-a) is supposed to explain why the presupposition triggered by the second conjunct (namely that Mary is pregnant) is “satisfied” by the first conjunct, and thus why (i-b) presupposes nothing.

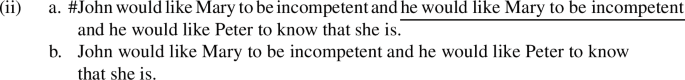

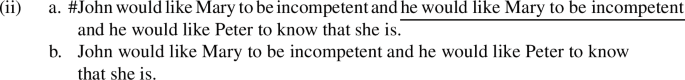

Schlenker (2008, 183–184) considers the desire verb ‘would like’, and observes that the underlined sentence in (ii-a) sounds redundant (compare this to (ii-b)). In terms of the satisfaction theory, this essentially amounts to saying that for verbs such as ‘would like’, presuppositions project into the subject’s desires.

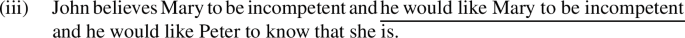

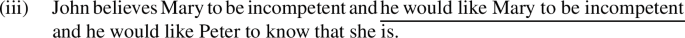

Schlenker also claims that the underlined sentence in (iii) is redundant, and on this basis seems to conclude that belief projection is captured in his 2008 theory.

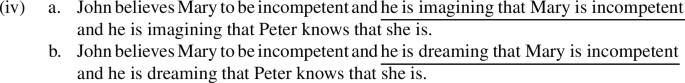

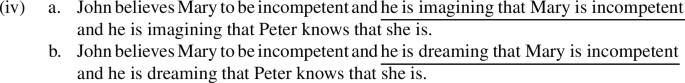

However, we don’t find the underlined sentence in (iii) to be redundant. Moreover, the underlined sentences in (iv-a) and (iv-b) are clearly not redundant:

So, at best Schlenker (2008) isn’t able to derive belief projection in full generality.

We let ‘BEST’ do notational double duty so that in this context it is a two-place function that maps an ordering source and a set of worlds A to the subset of top-ranked worlds in A, as ranked by the ordering source. f and g are functions from worlds to a set of propositions. w is as highly ranked by g(w) as v iff every proposition in g(w) that is true at v is also true at w. \(BEST(g(w), \cap f(w))\) is the set of worlds in \(\cap f(w)\) ranked highest by g(w).

See for example Heim (1992), von Fintel (1999) and Levinson (2003). A reviewer notes that the presupposition these authors posit for desire reports is stronger than that which we consider here: these authors maintain that both the complement and its negation must each be consistent with the agent’s beliefs. However, working with an entry that triggers this strengthened presupposition would make no difference to the results in this section. For example, the strengthened entry still satisfies the analogue of the claim in (21) (this can be confirmed by inspecting the proof of (21) in the Appendix).

See (b) in the Appendix. Here, we draw on analogous points about indicative conditionals from Mandelkern and Romoli (2017).

In passing, Sudo (2014, n. 7) suggests that the belief compatibility inference triggered by verbs such as want could stem from a competition effect with genuine presupposition triggers, e.g. glad. That is, the effect could be an “antipresupposition”. See Percus (2006), Sauerland (2008) and Chemla (2007) for related discussion, and Grano and Phillips-Brown (2021) for criticism.

See (c) in the Appendix.

We will consider a possible way for proponents of Schlenker’s account to respond to belief filtering data such as (26) in Sect. 6.

Mandelkern and Romoli (2017) show that when Schlenker’s local context algorithm is combined with a range of semantics for conditionals, it makes incorrect predictions for their target conditional constructions. They then proceed to make two further claims: (i) adding a presupposition to the semantics for conditionals to the effect that the antecedent is possible allows Schlenker’s theory to derive the right results for the initial data; but (ii) even assuming a possibility presupposition for conditionals, one can construct more complex examples that still pose a problem for Schlenker’s account (these examples engage the “symmetric” version of Schlenker’s algorithm). In some ways our arguments involving belief compatibility presuppositions are simpler than Mandelkern and Romoli’s (2017) results, since at best belief presuppositions don’t even apply to the full range of attitudes that exhibit belief projection.

See (d) in the Appendix.

See (e) in the Appendix.

(29) departs from Heim’s own entry in one respect. Heim assumes that \(Sim(w, \emptyset )\) is undefined. But granted plausible assumptions, this undefinedness condition induces the kind of compatibility presupposition we discussed in Sect. 4. Consequently, it is fairly easy to show that Heim’s original entry predicts belief projection. Since our goal in the current section is to explore the distinctive contribution of the belief-restricted comparative semantics to Schlenker’s local context algorithm, we instead assume that \(Sim(w, \emptyset ) = \emptyset \).

See (f) in the Appendix.

In fact, the result here extends beyond ‘wish’. Assuming a comparative similarity semantics for factives such as ‘regret’, ‘glad’, and ‘surprise’ (Cremers and Chemla, 2017; Guerzoni and Sharvit, 2007; Uegaki, 2015), variants of our proof show that these verbs are also predicted to have W as their local context.

There has been relatively little work on decision-theoretic accounts of wish reports. But plausible theories in this vein, for example those that appeal to imaging as the relevant belief revision mechanism rather than conditionalization, as in Blumberg (forthcoming), will also not derive belief projection. (See Gärdenfors, 1988; Joyce, 1999; Lewis, 1976, 1981; Sobel, 1994 for discussion of imaging and how it differs from conditionalization.)

Recently, theorists have developed analyses of verbs such as imagine on which these expressions denote two-dimensional concepts: instead of denoting functions from sets of worlds (propositions) to truth-values, they instead denote functions from sets of pairs of worlds (so-called “paired propositions”) to truth-values (Blumberg, 2018, 2019, forthcoming; Liefke and Werning, 2021; Maier, 2015, 2016, 2017; Ninan, 2008, 2016; Pearson, 2018; Yanovich, 2011). Although we do not do so here, it can be shown that these two-dimensional semantics also fail to derive belief projection. The key is that the second dimension of the complement’s content can be unrelated to the agent’s belief worlds.

Mackay (2019) argues that Schlenker’s algorithm makes incorrect predictions about counterfactual conditionals when combined with standard variably strict accounts of those constructions (Stalnaker, 1968; Lewis, 1973). But Mackay (2019) also shows that these problems can be avoided by restricting the domain of variably strict counterfactuals to a modal horizon (von Fintel, 2001). By contrast, there is no obvious semantics for fictive attitudes which will derive belief projection when combined with Schlenker’s algorithms.

A reviewer notes that the first-run quantificational entry for ‘want’ from Sect. 3 (\(\llbracket {\textsf {S wants p}}\rrbracket ^{w} = 1\) iff \(BEST(Bw) \subseteq \llbracket \textsf {p}\rrbracket \)) allows belief/want sequences to be explained without appealing to modal subordination. If ‘Bill thinks that Ann used to smoke’ is true, then all of Bill’s belief worlds are ones where Ann used to smoke. But then it trivially follows that all of Bill’s best belief worlds will be ones where Ann used to smoke as well. Whatever the merits of this approach to belief/want sequences, it clearly won’t carry over to belief/imagine sequences since, as remarked above, the set of worlds compatible with what a subject imagines needn’t be a subset of the subject’s belief set (indeed, the former can even be disjoint from the latter).

The same reviewer also wonders whether the conditional presuppositions that Schlenker’s algorithm predicts for belief/imagine sequences are necessarily problematic. The reviewer maintains that there is a close connection between belief and imagination, so that propositions of the form If S believes p, then S imagines p should often be acceptable. In response, we agree that belief and imagination are related, but we doubt that this connection is robust enough to make the relevant conditionals sufficiently plausible to competent speakers. After all, subjects can imagine things that contradict their beliefs, so for virtually no proposition p will If S believes p, then S imagines p be unsurprising. By contrast, belief/imagine sequences are perfectly acceptable out of the blue. Moreover, it is reasonable to think that dreaming is less connected to belief than imagining is, and yet belief/dream sequences also do not carry any presuppositions.

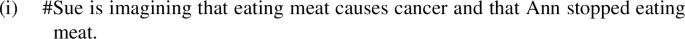

Examples that could be relevant here are ones like the following. Suppose that Sue believes that Ann eats meat and that eating meat does not cause cancer. Also suppose that Sue believes that, if eating meat caused cancer, then Ann would never have eaten meat in the first place.

(i) is infelicitous here, which isn’t predicted by belief projection. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for helpful discussion.

Note that a similar result holds for wish reports if we assume the entry for ‘wish’ from Sect. 4: the presuppositions predicted by Schlenker’s algorithm are strictly stronger than those predicted by belief projection.

It is worth observing that strengthening in proviso cases also appears to be mandatory. For instance, ‘I don’t know if Bart has a wife, but if he likes sonnets, then his wife does too’ is infelicitous. If this is correct, then perhaps being forced to posit mandatory strengthening in order to derive belief projection isn’t too much of a theoretical cost. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for helpful discussion here.

A further argument for belief projection concerns the observation that presuppositions triggered inside the scope of attitude verbs tend to rise to the matrix level, i.e. hearers tend to assume that the presupposition holds at the matrix context. For instance, ‘Bill wants Ann to stop smoking’ suggests that Ann used to smoke. This data point is called the e-inference in the literature on presupposition projection (Geurts, 1999; Maier, 2015). Building on Karttunen (1974) and Heim (1992) explains the e-inference in terms of belief projection. The idea is that when we process attitude reports, we usually assume that the subject’s beliefs agree with the common ground. When this occurs, the e-inference goes through. By contrast, on Schlenker’s theory it is perhaps harder to see how the e-inference could go through. However, as Geurts (1999) points out, Heim’s “belief agreement” assumption is problematic, for an example such as ‘Paul is not aware that Sue believes she has a cello’ does not lead to the inference that Sue has a cello. So, it is arguable that proponents of belief projection don’t have a satisfying account of the e-inference either (though see Sudo, 2014 for a defense). Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for helpful discussion here.

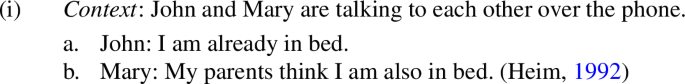

It is worth noting that there are some cases which do not pattern with belief projection. These involve a particular type of presupposition trigger, namely additive particles such as ‘too’ and ‘also’. These expressions are usually taken to trigger presuppositions linked to aspects of the conversational context. But these presuppositions needn’t constrain a subject’s beliefs (Geurts, 1999). For instance, consider Mary’s response in (i-b):

It is standardly assumed that the presupposition triggered by ‘Mary is also in bed’ is that there is a conversationally salient proposition to the effect that someone distinct from Mary is in bed (Kripke, 2009; Tonhauser et al., 2013). Thus, theories that conform to belief projection predict that (i-b) should only be acceptable if Mary’s parents believe that this proposition is salient in the minds of the interlocutors. But this clearly isn’t the case: Mary’s reply is perfectly felicitous even if her parents don’t believe that she’s speaking to John.

However, examples involving additive particles also pose a problem for Schlenker’s theory. For instance, Schlenker’s algorithm also predicts that the local context of the complement of a belief report is the subject’s beliefs. Thus, Schlenker’s account also predicts that (i-b) should only be acceptable if Mary’s parents believe that the proposition that someone distinct from Mary is in bed is salient in the minds of the interlocutors. So, additive particles pose a problem for the satisfaction theory in general, and don’t give us reason to favor Schlenker’s theory over more standard accounts. (For further discussion of some of the problems posed by additive particles, see Soames (1982), Romoli (2012) and Mandelkern and Romoli (2017).)

Belief projection has consequences for more than just Schlenker’s (2009) proposal. Rothschild (2011) attempts to solve the explanatory problem for dynamic semantics by defining a class of well-behaved “rewrite” semantic values for logical connectives, and deriving projection properties in terms of constraints on the class of rewrite semantics. That research program, however, is conspicuously silent on the semantics of attitude verbs, and for good reason. In rewrite semantics, the context change potentials of connectives are defined in terms of a sparse set of ingredients, including function composition and Boolean operations. In that framework, there is no way to non-arbitrarily narrow down the class of possible local contexts for attitude verbs. So belief projection is left unexplained.

However, Philippe Schlenker (p.c.) draws attention to an argument against accounts that simply stipulate the local contexts of attitude verbs. This is that there appears to be no cross-linguistic variation with respect to presupposition projection out of attitude verbs: within and across languages, if two attitude verbs V and \(V'\) have the same bivalent content, then they project presuppositions in identical ways as well. This would be surprising if local contexts were purely lexically specified, but would be expected on more general theories.

If \(Sim(w, \emptyset )\) is undefined (making \(Sim(w, \emptyset ) > p\) and \(p > Sim(w, \emptyset )\) undefined for any p), then the proof is straightforward.

See the beginning of the previous proof for our assumptions about Sim, as well as the relationship between the ordering over propositions > and the ordering over worlds \(\succ \).

References

Anand, P. (2007). Dream report pronouns, local binding, and attitudes de se. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 17, 1–18.

Anvari, A., & Blumberg, K. (2021). Subclausal local contexts. Journal of Semantics, 38(3), 393–414.

Beaver, D. I., Geurts, B., & Denlinger, K. (2021). Presupposition. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2021 edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/presupposition. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Berto, F. (2018). Aboutness in imagination. Philosophical Studies, 175, 1871–1886.

Blumberg, K. (2018). Counterfactual attitudes and the relational analysis. Mind, 127(506), 521–546.

Blumberg, K. (2019). Desire, imagination, and the many-layered mind. Ph.D. thesis, New York University.

Blumberg, K. (2022). Attitudes, presuppositions, and the binding theory. Ms., AUC

Blumberg, K. H. (forthcoming). Wishing, decision theory, and two-dimensional content. Journal of Philosophy.

Chemla, E. (2007). An epistemic step for anti-presuppositions. Journal of Semantics, 25(2), 141–173.

Chierchia, G., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2000). Meaning and grammar: An introduction to semantics. Cambridge, MA MIT Press.

Cremers, A., & Chemla, E. (2017). Experiments on the acceptability and possible readings of questions embedded under emotive-factives. Natural Language Semantics, 25(3), 223–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-017-9135-x.

Crnič, L. (2011). Getting even. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Gärdenfors, P. (1988). Knowledge in flux: Modeling the dynamics of epistemic states. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Geurts, B. (1996). Local satisfaction guaranteed: A presupposition theory and its problems. Linguistics and Philosophy, 19(3), 259–294.

Geurts, B. (1999). Presuppositions and pronouns. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Grano, T., & Phillips-Brown, M. (2021). forthcoming). (Counter) Factual want ascriptions and conditional belief. The Journal of Philosophy.

Guerzoni, E., & Sharvit, Y. (2007). A question of strength: on NPIs in interrogative clauses. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(3), 361–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-007-9014-x.

Heim, I. (1983). On the projection problem for presuppositions. In Reprinted in P. Portner & B. H. Partee (Eds.), Formal semantics—The essential readings (pp. 249–260). Oxford: Blackwell, 2002.

Heim, I. (1990). Presupposition projection. In R. van der Sandt (Ed.), Reader for the Nijmegen workshop on presupposition, lexical meaning, and discourse processes. University of Nijmegen.

Heim, I. (1992). Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics, 9(3), 183–221.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Knowledge and belief. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Iatridou, S. (2000). The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry, 31(2), 231–270.

Jerzak, E. (2019). Two ways to want? Journal of Philosophy, 116(2), 65–98.

Joyce, J. M. (1999). The foundations of causal decision theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karttunen, L. (1973). Presuppositions of compound sentences. Linguistic Inquiry, 4(2), 169–193.

Karttunen, L. (1974). Presupposition and linguistic context. Theoretical Linguistics, 34(1), 181.

Karttunen, L., & Peters, S. (1979). Conventional implicature. In C.-K. Oh & D. Dineen (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics 11: Presupposition (pp. 1–56). New York: Academic Press.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What ‘must’ and ‘can’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1(3), 337–355.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H. J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches in world semantics. (pp. 38–74). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantik/Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research. (pp. 639–650). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kripke, S. A. (2009). Presupposition and anaphora: Remarks on the formulation of the projection problem. Linguistic Inquiry, 40(3), 367–386.

Lassiter, D. (2011). Measurement and modality: The scalar basis of modal semantics. Ph.D. thesis, New York University.

Levinson, D. (2003). Probabilistic model-theoretic semantics for ‘want’. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 13, 222–239.

Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1976). Probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities. Philosophical Review, 85(3), 297–315.

Lewis, D. (1981). Causal decision theory. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 59(1), 5–30.

Liefke, K., & Werning, M. (2021). Experimental imagination and the inside/outside-distinction. In N. Okazaki, K. Yada, K. Satoh, & M. Mineshima (Eds.), New Frontiers in Artificial intelligence: JSAI-IsAI Workshops 2020 (pp. 69–112). Cham: Springer

Mackay, J. (2019). Subjunctive conditionals’ local context. Linguistics and Philosophy, 42(3), 207–221.

Maier, E. (2009). Presupposing acquaintance: A unified semantics for de dicto, de re and de se belief reports. Linguistics and Philosophy, 32(5), 429–474.

Maier, E. (2015). Parasitic attitudes. Linguistics and Philosophy, 38(3), 205–236.

Maier, E. (2016). Referential dependencies between conflicting attitudes. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 46, 141–167.

Maier, E. (2017). Fictional names in psychologistic semantics. Theoretical Linguistics, 43(1–2), 1–46.

Mandelkern, M., & Romoli, J. (2017). Parsing and presuppositions in the calculation of local contexts. Semantics and Pragmatics, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.10.7.

Ninan, D. (2008). Imagination, content, and the self. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ninan, D. (2016). Imagination and the self. In A. Kind (Ed.), Routledge handbook of the philosophy of imagination (pp. 247–285). London: Routledge.

Pearson, H. (2018). Counterfactual de se. Semantics and Pragmatics, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.11.2.

Percus, O. (2006). Antipresuppositions. In A. Ueyama (Ed.), Theoretical and empirical studies of reference and anaphora: Toward the establishment of generative grammar as an empirical science. (pp. 52–73). Report, Kuyushu University.

Percus, O., & Sauerland, U. (2003). Prounoun movement in dream reports. In Proceedings of NELS, 33, 265–284.

Phillips-Brown, M. (2021). What does decision theory have to do with wanting? Mind, 130(518), 413–437.

Portner, P., & Rubinstein, A. (2012). Mood and contextual commitment. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 22, 461–487.

Roberts, C. (1996). Anaphora in intentional contexts. In: S. Lappin (Ed.), The handbook of contemporary semantic theory (pp. 215–600). Oxford: Blackwell.

Romoli, J. (2012). A solution to Soames’ problem: Presuppositions, conditionals, and exhaustification. International Review of Pragmatics, 4(2), 153–184.

Rothschild, D. (2011). Explaining presupposition projection with dynamic semantics. Semantics and Pragmatics, 4(3), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.4.3.

Rubinstein, A. (2012). Roots of modality. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Sauerland, U. (2008). Implicated presuppositions. In A. Steube (Ed.), The discourse potential of underspecified structures (pp. 581–600). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Scheffler, T. (2008). Semantic operators in different dimensions. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Schlenker, P. (2020). Inside out: A note on the hierarchical update of nominal modifiers. Glossa, 5(1), 60.

Schlenker, P. (2008). Be articulate: A pragmatic theory of presupposition projection. Theoretical Linguistics, 34(3), 157–212.

Schlenker, P. (2009). Local contexts. Semantics and Pragmatics, 2(3), 1–78. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.2.3.

Schlenker, P. (2010a). Local contexts and local meanings. Philosophical Studies, 151(1), 115–142.

Schlenker, P. (2010b). Presuppositions and local contexts. Mind, 119(474), 377–391.

Soames, S. (1982). How presuppositions are inherited: A solution to the projection problem. Linguistic Inquiry, 13, 483–545.

Sobel, J. H. (1994). Taking chances: Essays on rational choice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1974). Pragmatic presuppositions. Reprinted in R. Stalnaker, Context and content (pp. 47–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Stalnaker, R. (1984). Inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stalnaker, R. C. (1968). A theory of conditionals. In N. Rescher (Ed.), Studies in logical theory (American Philosophical Quarterly Monographs 2) (pp. 98–112). Oxford: Blackwell.

Stephenson, T. (2010). Vivid attitudes: Centered situations in the semantics of ‘remember’ and ‘imagine’. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 20, 147–160.

Sudo, Y. (2014). Presupposition satisfaction in attitude contexts and modal subordination. In L. Crnic & U. Sauerland (Eds.), The art and craft of semantics: A festschrift for Irene Heim. (Vol. 2, pp. 175–199). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tonhauser, J., Beaver, D., Roberts, C., & Simons, M. (2013). Toward a taxonomy of projective content. Language, 89(1), 66–109.

Uegaki, W. (2015). Interpreting questions under attitudes. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

van der Sandt, R. A. (1992). Presupposition projection as anaphora resolution. Journal of Semantics, 9(4), 333–377.

von Fintel, K. (1999). NPI licensing, Strawson entailment, and context dependency. Journal of Semantics, 16(2), 97–148.

von Fintel, K. (2001). Counterfactuals in a dynamic context. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language (pp. 123–152). Cambridge, MA:MIT Press.

Yalcin, S. (2007). Epistemic modals. Mind, 116(464), 983–1026.

Yanovich, I. (2011). The problem of counterfactual de re attitudes. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 21, 56–75.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Thanks to Matt Mandelkern, Philippe Schlenker, two anonymous reviewers at Linguistics and Philosophy, and our editor Luka Crnič for very helpful feedback and discussion. All errors are our own.

Appendix

Appendix

-

(a)

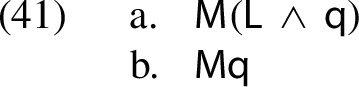

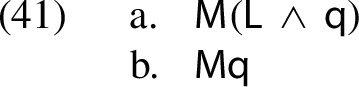

Where \(\textsf {M}\) is a Kratzerian modal, the local context of \(\textsf {p}\) in \(\textsf {M}\textsf {p}\) in global context C is \(\bigcup \left\{ \textsc {best}(g(w), \cap f(w)) \mid w \in C\right\} \). Proof. Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = \bigcup \left\{ BEST(g(w), \cap f(w)) \mid w \in C\right\} \). First, for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (41-a) and (41-b) are equivalent in C:

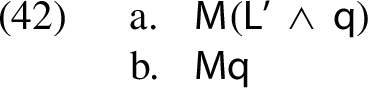

To see this, suppose \(w \models \textsf {M}({\textsf {L}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}})\), with \(w \in C\). Then \(Q_{\textsf {M}}\) of the worlds in \(BEST(g(w), \cap f(w))\) are \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \)-worlds. Since \(BEST(g(w), \cap f(w)) \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \), it follows that \(Q_{\textsf {M}}\) of the worlds in \(BEST(g(w), \cap f(w))\) are \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \)-worlds. So, \(w \models \textsf {M}{\textsf {q}}\) as well. Second, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) is the strongest restriction that creates contextual equivalence. To see why, consider a stronger restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world \(w' \in BEST(g(w), \cap f(w))\) for some \(w \in C\). Then contextual equivalence fails. The precise form of the counterexample depends on the quantification force of the modal under discussion. If \(Q_{\textsf {M}}\) quantifies universally, then let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Then (42-a) is false but (42-b) is true at w:

For \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) excludes \(w'\), so \(w' \not \in \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \,\wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \). But of course \(w' \in \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Analogous examples can be constructed for modals with different quantificational requirements. \(\square \)

-

(b)

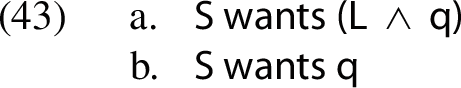

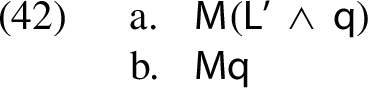

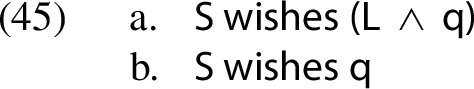

Given the semantics for want in (20) below, the local context of \({\textsf {p}}\) in \({\textsf {S wants p}}\) in global context C is \(\bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \).

Proof. We assume that at no world in C is the subject absolutely certain about which world they inhabit. We also assume that undefinedness is distinct from truth or falsity. Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = \bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \). First, it is clear that for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (43-a) and (43-b) are equivalent in C:

Second, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) is the strongest restriction that creates contextual equivalence. For consider a stronger restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world \(v \in Bw\) for some \(w \in C\). Suppose, \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \left\{ v\right\} \). Then contextual equivalence fails, because \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \emptyset \) so (44-a) will be undefined at w, but (44-b) will be true or false at w.\(\square \)

-

(c)

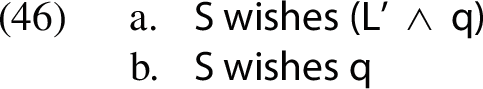

Given the semantics for wish in (24) below, the local context of \({\textsf {p}}\) in \({\textsf {S wishes p}}\) in global context C is \(\bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \cup \bigcup \left\{ BEST(Dw) \mid w \in C\right\} \).

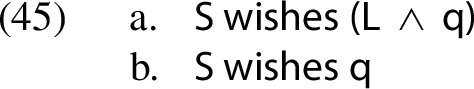

Proof. Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = \bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \cup \bigcup \left\{ BEST(Dw) \mid w \in C\right\} \). First, for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (45-a) and (45-b) are equivalent in C:

\({\textsf {S wishes q}}\) is defined in C iff \({\textsf {S wishes (L}} \wedge {\textsf {q)}}\) is defined : since \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) contains every belief world in the context, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \) is incompatible with the belief worlds iff \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \) is. Now suppose \({\textsf {S wishes q}}\) is true at w in C. Then \(BEST(Dw) \subseteq \llbracket \textsf {q}\rrbracket \). Since \(BEST(Dw) \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \), \({\textsf {S wishes (L}}\, \wedge {\textsf {q)}}\) is true at w in C as well. Conversely, if \({\textsf {S wishes (L}}\, \wedge {\textsf {q)}}\) is true at w in C, then \(BEST(Dw) \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \cap \llbracket \textsf {q}\rrbracket \) and so \(BEST(Dw) \subseteq \llbracket \textsf {q}\rrbracket \). Thus, \({\textsf {S wishes q}}\) is true at w in C. Second, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) is the strongest restriction that creates contextual equivalence. To see why, consider a stronger restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world v in either Bw or Best(Dw) for some \(w \in C\). First, suppose \(v \in Bw\). Then contextual equivalence fails, because (46-a) is false at w, while (46-b) is undefined, where \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \left\{ v\right\} \).

Second, suppose \(v \in Best(Dw)\). Then contextual equivalence fails, because (47-a) is false at w, while (47-b) is true, where \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W - Bw\).

\(\square \)

-

(d)

Given the semantics for want in (27) below, the local context of \({\textsf {p}}\) in \({\textsf {S wants p}}\) in global context C is W.

Proof. It will be helpful to make explicit our assumptions about the similarity function Sim. First, we assume that for any w, \(Sim(w, \emptyset ) = \emptyset \).Footnote 40 Second, we assume Strong Centering: if \(w \in p\), then \(Sim(w, p) = w\). Finally, we assume that any world in a subject’s belief set is more similar to the other worlds in the belief set than any worlds outside of it. That is, we assume that \(Sim(u, p) \subseteq Bw\), if \(u \in Bw\) and \(p \cap Bw \ne \emptyset \). Let us call this assumption Belief Similarity. We also follow Heim (1992) in defining >, an ordering over propositions, in terms of \(\succ \), a strict partial ordering over worlds. More explicitly: for any propositions p, q: \(p > q\) iff \(\forall w \in p\), \(\forall w' \in q: w \succ w'\). First, let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = W\). Then for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (48-a) and (48-b) are equivalent in C:

Second, \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \) is the strongest restriction that creates contextual equivalence. To see why, consider a stronger restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world v. We reason by cases, depending on whether \(v \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\) or not. (A) First, suppose \(v \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\). Then there is some \(w \in C\) such that \(v \in Bw\). Now we reason by cases again, depending on where v lies in \(\succ \) with respect to the other elements in Bw. (A1) Suppose that there is some \(v' \in Bw\) such that \(v' \ne v\) and \(v \not \succ v'\). Then let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{v\}\). Then (49-a) is true and (49-b) is false at w:

For \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \emptyset \), and so for all \(u \in Bw: Sim(u, \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) = \emptyset > Sim(u, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket )\). But \(\{v\} = Sim(v', \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \not > Sim(v', W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) = \{v'\}\), by Strong Centering and our assumptions about the relative ranking of v and \(v'\). (A2) Now suppose that for all \(v' \in Bw\) such that \(v' \ne v\): \(v \succ v'\). We reason by cases again, depending on whether \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \) or not. (A2i) Suppose that \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \). Then let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = Bw/\{v\}\). Given Belief Similarity, \(Sim(v, \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \subseteq Bw\), and by Strong Centering we have \(Sim(v, W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket )\) = \(\{v\}\). Given our assumption about the ranking of v, it follows that \(Sim(v, \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \not > Sim(v, W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket )\) and so (49-b) is false at w. But (49-a) is trivially true at w, since \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \emptyset \) given our assumption that \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \). (A2ii) Now suppose that \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw \ne \emptyset \). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Then (49-b) is trivially true at w. But by Belief Similarity, \(Sim(v, \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \subseteq Bw\), and by Strong Centering we have \(Sim(v, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket )\) = \(\{v\}\). Given our assumption about the ranking of v, it follows that \(Sim(v, \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \not > Sim(v, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket )\), and so (49-a) is false at w. This completes the case where \(v \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\). (B) Now suppose that \(v \not \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\). We reason by cases again, depending on whether v outranks all of the elements in \(\bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\) or not. (B1) Suppose that for some \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\), \(v \not \succ v'\). Then there is some \(w \in C\) such that \(v' \in Bw\). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{v\}\). Then \(\{v\} = Sim(v', \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \not > Sim(v', W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) = \{v'\}\), given Strong Centering and our assumption about the ranking of v. So, (49-b) is false at w. But (49-a) is trivially true at w. (B2) Now suppose that for all \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\), \(v \succ v'\). We reason by cases again, depending on whether every \(s \in W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) outranks every \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\) or not. (B2i) Suppose that there is some \(s \in W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \), and some \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\), such that \(s \not \succ v'\). Then we reason by cases again, essentially recapitulating the cases that we have already seen. To make things readable, let us denote the subcases for (B2i) with strings beginning with capital roman numerals, e.g. I, II, etc. (I) Suppose that \(s \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\). Then there is some \(w \in C\) such that \(s \in Bw\). Now we reason by cases again, depending on where s lies in \(\succ \) with respect to the other elements in Bw. (I1) Suppose that there is some \(s' \in Bw\) such that \(s' \ne s\) and \(s \not \succ s'\). Then let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{s\}\). Then (49-a) is true and (49-b) is false at w [the justification is essentially the same as for the analogous claims made in (A1)]. (I2) Now suppose that for all \(s' \in Bw\) such that \(s' \ne s\): \(s \succ s'\). We reason by cases again, depending on whether \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \) or not. (I2i) Suppose that \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \). Then let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = Bw/\{s\}\). For reasons similar to those given in (A2i), (49-b) is false at w, but (49-a) is trivially true at w. (I2ii) Now suppose that \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw \ne \emptyset \). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Then (49-b) is trivially true at w. But (49-a) is false at w, for reasons similar to those given in (A2ii). (II) Now suppose that \(s \not \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\). Recall that we are assuming that there is some \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\), such that \(s \not \succ v'\). Then there is some \(w \in C\) such that \(v' \in Bw\). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{s\}\). Then for reasons similar to those given in (B1), (49-b) is false at w, but (49-a) is trivially true at w. This completes the case where there is some \(s \in W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \), and some \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\), such that \(s \not \succ v'\). (B2ii) Suppose that for all \(s \in W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \), and for all \(v' \in \bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\): \(s \succ v'\). It follows that \(\bigcup _{w \in C}Bw \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \). Now let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Let \(w \in C\) be arbitrary. Then (49-b) is trivially true at w. But given Belief Similarity, for any \(u \in Bw\): \(Sim(u, \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \,\wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \subseteq Bw\), since \(Bw \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \). Moreover, since \(W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) is comprised of elements that dominate \(\bigcup _{w \in C}Bw\) and thus Bw, \(Sim(u, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) = Sim(u, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket )\) is comprised of elements that dominate Bw. Hence, \(Sim(u, \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \not > Sim(u, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}}\rrbracket )\), and (49-a) is false at w. This completes the proof. \(\square \)

-

(e)

Given the semantics for want in (29) below, the local context of \({\textsf {p}}\) in \({\textsf {S wants p}}\) in global context C is \(\bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \).Footnote 41

Proof. First, let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = \bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \). Then for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), the following are equivalent in C:

Here, the key observation is that \(Sim(w', \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = Sim(w', \llbracket {\textsf {L}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw)\), and \(Sim(w', \llbracket \lnot {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = Sim(w', \llbracket \lnot {\textsf {(L}} \wedge {\textsf {q)}}\rrbracket \cap Bw)\). After all, for any \(w \in C\), \(Bw \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \). It follows that \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap (\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = (\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \cap \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) \cap Bw = \llbracket {\textsf {L}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw\); and that \(\llbracket \lnot {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = (W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) \cup \emptyset = (W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) \cup (W/\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = (W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cup W/\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket ) \cap Bw = (W/(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap \llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket )) \cap Bw = (W/(\llbracket {\textsf {L}} \,\wedge \,{\textsf {q}}\rrbracket ) )\cap Bw = (\llbracket \lnot ({\textsf {L}} \wedge {\textsf {q}})\rrbracket ) \cap Bw\). Second, consider another restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world \(w' \in \bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \). There must be some \(w \in C\) such that \(w' \in Bw\). Now we reason by cases, depending on whether \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) contains worlds in Bw or not. First, suppose \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \). Then we reason by cases again, depending on where \(w'\) lies in \(\succ \) (we assume that \(\succ \) is restricted to Bw). First, suppose that \(w'\) outranks the other elements in Bw. Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W/\{w'\}\). Then the semantic values of (51-a) and (51-b) will diverge at w. The former will be trivially true, since \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw = \emptyset \), and so for all \(v \in Bw: Sim(v, \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = \emptyset > Sim(v, W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw)\). But the latter will be false, since \(Sim(w', \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) \not > Sim(w', W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = \{w'\}\) (assuming Strong Centering, and given our assumption that \(w'\) is the greatest element).

Now suppose \(w'\) is not greatest. Then there is some \(w'' \in Bw\) such that \(w' \not \succ w''\). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{w'\}\). Then the semantic values of (51-a) and (51-b) will again diverge at w: the former will be trivially true, but the latter will be false since \(\{w'\} = Sim(w'', \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) \not > Sim(w'', W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = \{w''\}\) (again given Strong Centering and our assumption that \(w'\) is not greatest). Now suppose that \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap Bw \not = \emptyset \). Suppose that \(w'\) is greatest. Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = W\). Then the semantic values of (51-a) and (51-b) will diverge at w. The former will be false, since \(w' \in W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw\), and so \(\emptyset \ne Sim(w', \llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) \not > Sim(w', W/\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \wedge {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = \{w'\}\) (again given Strong Centering and assuming that \(w'\) is greatest). But the latter will be trivially true. Now suppose \(w'\) is not greatest. Then there is some \(w'' \in Bw\) such that \(w' \not > w''\). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{w'\}\). Then the semantic values of (51-a) and (51-b) will diverge at w. The former will be trivially true, since \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \cap \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \emptyset \). But the latter will be false since \(\{w'\} = Sim(w'', \llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) \not > Sim(w'', W/\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket \cap Bw) = \{w''\}\) (again given Strong Centering and our assumption that \(w'\) is not greatest). This completes the proof. \(\square \)

-

(f)

Given the semantics for \({\textsf {want}}\) in (31), the local context of \({\textsf {p}}\) in \({\textsf {S wants p}}\) in global context C is \(\bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \).

Proof. First, let \(\llbracket {\textsf {L}}\rrbracket = \bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \). Then since Pw assigns positive probability to all and only belief worlds, it is clear that for any sentence \({\textsf {q}}\), (52-a) and (52-b) are equivalent in C:

Second, consider another restriction \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}}\rrbracket \) that excludes some world \(w' \in \bigcup \left\{ Bw \mid w \in C\right\} \). There must be some \(w \in C\) such that \(w' \in Bw\). Let \(\llbracket {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \{w'\}\). Then \(\llbracket {\textsf {L'}} \ \wedge \ {\textsf {q}}\rrbracket = \emptyset \). Now, for any credence function Pw, and proposition p, \(Pw(p | \emptyset )\) is undefined. It follows that (53-a) will be undefined at w, but (53-b) will be true or false at w.

\(\square \)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blumberg, K., Goldstein, S. Attitude verbs’ local context. Linguist and Philos 46, 483–507 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09373-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09373-y