Abstract

Newly-established adsorption enthalpy and entropy values of 12 lanthanide hexafluoroacetylacetonates, denoted Ln[hfac]4, along with the experimental and theoretical methodology used to obtain these values, are presented for the first time. The results of this work can be used in conjunction with theoretical modeling techniques to optimize a large-scale gas-phase separation experiment using isothermal chromatography. The results to date indicate average adsorption enthalpy and entropy values of the 12 Ln[hfac]4 complexes ranging from −33 to −139 kJ/mol K and −299 to −557 J/mol, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rising nuclear security concerns surrounding the safety and proliferation of nuclear materials used in nuclear power plants, in addition to possible diversion of materials for illicit purposes by nuclear terrorists, calls for the development of novel technologies for rapid response to such potential threats. The heavy fission product spectrum is largely comprised of lanthanide elements which have been subsequently used by many researchers as characteristic nuclear forensic signatures of fissile (e.g., uranium, plutonium) materials that could be targeted by terrorists. An investigation of lanthanide chelate adsorption characteristics provides important information contributing to pre- and post-detonation nuclear forensic techniques. Previous work has detailed the importance of these values as they pertain to post-detonation nuclear forensics [1]. We formerly established the theoretical plausibility of gas-phase separations using lanthanide chlorides in Monte Carlo simulations [2, 3], and afterward demonstrated successful detection of Ln[hfac]4 complexes using a gas chromatography (GC) instrument coupled to an inductively-coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometer (ICP-TOF-MS) [4]. We now present experimentally-determined adsorption enthalpies that can be used in a theoretical model to optimize an isothermal gas-phase separation experiment using the GC–ICP-TOF-MS setup. Following established adsorption enthalpy methodology using temperature ramping in a chromatographic system, Ln[hfac]4 deposition patterning in a quartz column enabled the convergence of these valuable thermodynamic values.

Experimental method

If a suite of complexes, in this case the Ln[hfac]4 complexes, demonstrate variation in volatilization temperatures, a temperature gradient or ramped temperature chromatography method can be used to experimentally determine adsorptive thermodynamic characteristics. Each complex will elute from the column at a characteristic temperature directly correlated to its thermodynamic properties. This temperature can be used in conjunction with experimental operating conditions to converge the enthalpy and entropy of adsorption of the complexes.

Steffen and Bachmann [5] have outlined a derivation used to calculate the entropy and enthalpy of adsorption from deposition patterns within a temperature gradient. The equation resulting from this derivation is described in (1) as:

where t a is the time of adsorption, ΔH° is the enthalpy of adsorption (unknown), R is the ideal gas constant, T a is the adsorption temperature, ΔS° is the entropy of adsorption (unknown), s is the open surface area of the column per unit length, T 0 is the original temperature, a is the temperature gradient, u 0 is the linear flow velocity, and V 0 is the open volume of the column per unit length.

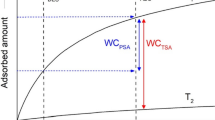

When several experiments are performed at various operating conditions (changing, for example, the linear gas velocity u 0), and the resulting lines derived from the above equation are plotted on a graph of enthalpy of adsorption versus entropy of adsorption, the intersection of the lines yields the resulting enthalpy and entropy of adsorption of the complex under interrogation.

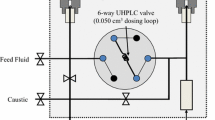

In lieu of a temperature gradient, a procedure using cold column complex deposition and temperature ramping was used to mimic the conditions a temperature gradient provides. One end of the quartz column was introduced to room temperature conditions while the other end remained connected to the injection port of the GC instrument, where the injected sample could be flash vaporized. The majority of the column was within the GC oven where the temperature could be easily controlled with only the last 5–6 cm of column remaining in room temperature conditions. A given Ln[hfac]4 complex was injected at a sufficiently high temperature such that it traversed the length of the column and deposited on the last 5–6 cm where it was exposed to a sudden negative temperature gradient. The end with the complex deposit was then coiled into a cooled GC with the remainder of the column and subjected to a gradual temperature increase. Each temperature point was held for 10 min, after which the column was inspected for remaining deposition. The temperature was increased until the deposit eluted within the 10-min timeframe. Using this method, we were able to confine a 5-degree window (or less) in which the complex would elute; this temperature is the temperature at which the complex becomes a gas and elutes at the given operational conditions, and conversely, the deposition temperature at which the complex condenses from a gas to a solid within the column. A temperature gradient provides the same information this method produces; namely, both methods allow the deposition temperature to be measured using experimental parameters. Using this deposition range and known operating conditions, T 0 and T a were assumed to be the beginning and end of the measured deposition temperature range, while t a was assigned a value that allows the complex to adsorb at the midpoint of this range, giving a deposition temperature equal to the midpoint of the experimental temperature deposition values.

With the known conditions described above in conjunction with other operating conditions, all necessary variables can be substituted into the derived equation and plotted to yield linear equations. Performing the same experiment with the same complex, but varying the carrier gas flow rate, produces a line with a slightly different slope that intersects the first line under the original operating conditions. This intersection yields the enthalpy and entropy of adsorption values. The more experiments performed at varied conditions for a given complex, and subsequently the more lines plotted for those experiments, the more the error can be reduced and mitigated.

Results

Samples of individual Ln[hfac]4 complexes, aside from La[hfac]4, Ce[hfac]4, and Pm[hfac]4, were injected according to the methodology outlined in the previous chapter to observe and isolate deposition temperature ranges along the column. Four pressure values were initially used to discern temperature variances as they related to column pressure; however, after injecting several samples at the highest pressure value of 42 psi, it was observed that the adsorption properties of the complexes were completely overridden by the high pressure within the column. A minimum tank pressure of 10 psi (physical limitation) and maximum pressure of 42 psi (thermodynamic limitation) left an acceptable range of three individual pressures: 12, 22, and 33 psi, to be used. Adding more pressure values within this range did not allow for sufficient discernment of deposition temperature ranges between the pressure values, so in the end, only these three pressure values were used to measure the adsorption properties of the complexes. Resulting deposition temperature ranges are shown in Table 1.

The temperature deposition profiles of each element were used to model adsorption behavior using the equation outlined in the previous section. In conjunction with pressure, deposition temperature, flow rate, and other operating conditions, adsorption enthalpy and entropy values could be plotted at each temperature value and graphed concurrently. The three points of intersection of these lines (produced from the three pressure values used during experimentation and subsequent variations in deposition temperature) relay three converged entropy and enthalpy values for each complex. Under ideal conditions, these points would all overlap and convey a single value for enthalpy and entropy of adsorption. However, due to experimental error, the three points of intersection must be averaged. Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 show the plots resulting from the data obtained in Table 1.

The points of intersection of the lines shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 are averaged and indicated in Table 2, along with the standard deviation from both experimental and theoretical error. Figures 13 and 14 show these values graphically.

Conclusions

The enthalpy and entropy of adsorption of 12 lanthanide hexafluoroacetylacetone chelates have been experimentally measured for the first time. These values were determined using a modified temperature gradient method to observe deposition temperature patterning along an uncoated quartz column in a variety of operational conditions. These experimentally-determined thermodynamic values are vital input parameters for theoretical models to optimize experimental conditions for a large-scale gas-phase separation of heavy fission product chelates using hexafluoroacetylacetone. Even if the measured thermodynamic values, once used in the model, do not result in predicted separations in the gas phase using this ligand, these adsorption values remain valuable to the thermodynamic community to corroborate other thermodynamic models using volatile lanthanide complexes.

References

Auxier JD II, Jordan JA, Stratz SA et al (2015) Thermodynamic analysis of volatile organometallic fission products. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. doi:10.1007/s10967-015-4653-9

Hanson DE, Garrison JR, Hall HL (2011) Assessing thermochromatography as a separation method for nuclear forensics: current capability vis-a-vis forensic requirements. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. doi:10.1007/s10967-011-1063-5

Garrison JR, Hanson DE, Hall HL (2011) Monte Carlo analysis of thermochromatography as a fast separation method for nuclear forensics. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 291:885–894. doi:10.1007/s10967-011-1367-5

Stratz SA, Jones SA, Oldham CJ et al (2016) Gas-phase detection of solid-state fission product complexes for post-detonation nuclear forensic analysis. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. doi:10.1007/s10967-016-4920-4

Steffen A, Bachmann K (1978) Gas chromatographic study of volatile oxides and hydroxides of Re, Tc, Os, Ru, and Ir-II. Thermochromatogr Investig 25:677–683

Acknowledgements

This work was performed under Grant Number DE-NA0001983 from the Stewardship Science Academic Alliances (SSAA) Program of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the DOE or NNSA. This material is also based upon work supported by the US Department of Homeland Security under Grant Award Number, 2012-DN-130-NF0001. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the US Department of Homeland Security. Manny Mathuthu is grateful to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for awarding him Fellowship Grant No. SAF/15007 to visit and undertake research at the Institute for Nuclear Security (INS) at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He would also like to thank Dr. Howard Hall and Natacha Peter Stein Liliane at INS for hosting him for the duration of his fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Stratz, S.A., Jones, S.J., Mullen, A.D. et al. Gas chemical adsorption characterization of lanthanide hexafluoroacetylacetonates. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 312, 355–360 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-017-5232-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-017-5232-z