Abstract

The extant literature shows that innovation emerges from an interorganizational process, where a division of labor (both exploitation and exploration related) occurs among the actors within the cluster. Clustered firms are ambidextrous when they balance innovative activities that exploit existing competencies and are open to new technological approaches through exploration. In this context, we are interested in the role of clusters as supportive structures creating an atmosphere that encourages the development of interorganizational relationships, which assume a key relevance in explaining the ambidexterity and innovation of firms within the cluster. The question is whether there is an ideal combination to compete today (exploitation) while preparing to compete tomorrow (exploration), and if the networks developed in an industrial cluster play a role on determining innovative performance. Therefore, this study contributes to deepen the knowledge about the role of ambidexterity and network clustering on innovation. Specifically, by presenting a framework that explores the influence of external stakeholders and other clustered agents in the response of ambidextrous organizations to the challenges raised by environmental changes, we extend our discussion to a higher level of abstraction showing how ambidexterity can be the “black box” that connects the entrepreneurship, management, and innovation fields. The analysis of 1467 Portuguese firms suggests that network clustering has a direct positive impact on innovative performance, but also an indirect, mediated effect through exploration. Additionally, we found that a combination of exploitation and exploration (i.e., combined ambidexterity), and the trade-off between the two dimensions (i.e., imbalanced ambidexterity), leads to better innovation in agglomeration contexts. Our results, therefore, provide evidence that ambidexterity is the key to manage innovation strategic entrepreneurship’s tensions but, the way in which they are managed, is contingent on the clustered firms’ ability or inability to simultaneously pursue both exploitation and exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Firms focused on innovation develop their knowledge base in two different ways: (1) they are constantly refining the portfolio of products and increasing the production process efficiency, and (2) to remain competitive in the long-term, they explore novel technological ways to develop new capabilities that bring future revenue (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004). This ability to, simultaneously, pursue exploitation and exploration is called ambidexterity, a concept that was originally developed by Duncan (1976) and March (1991). Nevertheless, engaging, simultaneously, in exploratory and exploitative activities is a challenging effort to allow the firms’ development (March, 1991). However, academic literature has been recognizing the importance of firms achieving ambidexterity, i.e., to engage in incremental innovation—exploitation, while also promoting radical innovation—exploration (Junni et al., 2013).

The idea that innovation plays a vital role on the firms’ survival has been widely accepted on the literature (Nobakht et al., 2020). Previous studies emphasize that innovation is the main responsible for value creation (Hauser et al., 2006), allowing the firms’ adaptation to dynamic environments (Urabe et al., 2018). Therefore, entrepreneurial innovations result from a continuous interaction of different players (Guerrero & Urbano, 2019), involving the recognition of opportunities (Guerrero et al., 2008), and the establishment of communication channels, able to enhance the innovative process (Baumol, 1993).

Based on the above, we apply the concept of ambidexterity to the cluster level since these structures facilitate learning and knowledge flows, while also fostering cooperative activities between local actors (Porter, 1998). We ask to what extent can and do clustered firms use cooperation in industrial clustersFootnote 1 to develop both exploitation and exploration. Overall, cluster cooperation can be useful in both activities: (1) the interorganizational relationships developed within clusters can help firms to improve their knowledge base with the danger of overly focusing on the development of existing competencies (exploitation); (2) cooperation in industrial clusters can also provide new impulses that lead to new competencies required for the development of disruptive products (exploration) (Wolf et al., 2019).

The extant literature examines industrial clusters through the organic development of competences at the firm level (e.g., Fornahl et al., 2015; Keeble & Wilkinson, 1999): the interorganizational relationships developed within the cluster allow firms to improve their existing capabilities and increase their competitiveness. Based on these studies, and on the recent works of Bocquet and Mothe (2015) and Wolf et al. (2019) in cluster ambidexterity, one can ask whether and under what circumstances cooperation in industrial clusters can contribute to ambidexterity and innovation. Thus, by extending the level of analysis, we shift perspective and examine if clustered firms are ambidextrous, assuming that ambidexterity is necessary for long-term success. According to Kauppila (2007), ambidexterity among clustered firms can unfold in two ways: (1) clusters achieve ambidexterity when all actors are ambidextrous, or (2) clusters become ambidextrous as each of the actors focus on either exploration or exploitation.

Therefore, industrial clusters can be seen as social systems in which firms are embedded, being able to drive exploitation and exploration while also promoting innovative behavior. We, then, propose to test a framework that might explain the influence of stakeholders and eco-systems’ agents in the response of ambidextrous organizations to the challenges raised by social, technological, and economic changes. We follow the reasoning of Wolf et al. (2019), who stated that cluster policies influence cluster dynamics by providing stimulus for the development of agglomerated firms, directly influencing cooperative behavior. The design of these policies determines some framework conditions to the firms’ activities and might, therefore, influence the strategies addressing the ambidexterity challenges. In this setting, cluster management organizations are “intermediaries” that support the actors within the cluster to satisfy their needs (in respect to ambidexterity and innovation in cooperation strategies). Clustered firms, in this context, constitute a particular interesting research domain due to the close interplay between entrepreneurial opportunities available for them, the resource allocation decisions, and the interorganizational innovation system, allowing to explore the potential innovation strategic entrepreneurship’s tensions. In other words, the ability or inability of clustered firms to, simultaneously, adopt exploitation and exploration determines how decision-makers position themselves within the interorganizational networks (entrepreneurial-related ambidexterity), as well as how they decide to allocate clustered firms’ resources (managerial-related ambidexterity) to achieve the highest incremental and/or radical innovative outcomes (innovation-related ambidexterity).

Thus, the aim of this study is to shed light on which ambidexterity dimension helps clustered firms to achieve a higher innovative performance, considering the role played by the interorganizational relationships. The implications for theory and practice are threefold. First, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how tensions in the two interrelated areas of entrepreneurship (i.e., managers position in the interorganizational networks) and management (i.e., resource allocation decisions) affect each other and result in the ambidexterity of the clustered firms’ innovation systems. This adds to the literature on innovation and, particularly, on ambidexterity as an innovation paradox (e.g., Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009). Second, our research contributes to the entrepreneurship literature on clustered firms, which has been acknowledged as providing constantly emerging paradoxes, as well as unique characteristics and dynamics when it comes to innovation-related decisions (Fotso, 2022; Speldekamp et al., 2020; Wolf et al., 2019). This paper answers previous research calls to investigate how a cluster can be ambidextrous (Kauppila, 2007) based on the existence and the form of division of labor activities in respect to exploitation and exploration (Wolf et al., 2019). Third, this study adds to the management literature, specifically, on organizational paradoxes that stem from resource allocation decisions. Empirical evidence is added to the interorganizational ambidexterity literature (Marco-Lajara et al., 2022) proposing that the way in which managers deal with the constant environmental challenges plays an important role in organizational outcomes, particularly, on innovative performance.

To address the research purpose, the database used is the Community Innovation Survey (CIS, 2012). The empirical analysis was carried out on a sample of 1467 Portuguese firms covering a timeframe of three years (2010–2012). According to the European Innovation Scoreboard, Portugal is a small open economy characterized by its strong innovation index (EIS, 2020). Since small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are highly innovative, Portugal assumes a leadership position revealing high shares of innovative products and business processes (EIS, 2020). Based on these indicators, we conducted our study on ambidexterity among four industrial clusters: (1) Footwear and Fashion, (2) Textile—Technology and Fashion, (3) Petrochemical, Industrial Chemistry and Refining, and (4) Automotive. Since the Portuguese industrial clusters require applicants to develop a common strategy and promote regional development, the question arises whether clustered firmsFootnote 2 used interorganizational relationships in order to cope with the individual challenges of creating an environment that allows organizational ambidexterity. For all of these reasons, the Portuguese economy represents a relevant setting for this study.

By using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), the current study provides interesting evidence of the network clustering-innovation relationship, expanding the literature on the topic. As managers of innovation-oriented firms are concerned with making correct choices about resource allocation that influence business prosperity, these findings may help to broaden the field of ambidexterity as the missing link between entrepreneurship, management, and innovation, by identifying the antecedents of the firms’ innovative performance.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, we present a review of the literature and propose the empirical hypotheses. This is followed by an explanation of the methodology, as well as the description and discussion of the findings. Then, the contributions of the study are presented, and the paper closes with the main limitations and avenues for future research.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Organizational ambidexterity

Over the last years, the concept of ambidexterity has increasingly become the field of research for many scholars (Amjad & Nor, 2020; Wilden et al., 2018). The extant literature has introduced the term organizational ambidexterity to describe two contradictory and seemingly incompatible activities of exploitation and exploration. Exploration refers to behaviors characterized by search, discovery, experimentation, risk-taking, and innovation, while exploitation involves the adoption of activities related to refinement, implementation, efficiency, production, and selection (Levinthal & March, 1993; March, 1991). Therefore, the returns associated with exploration are more variable and distant in time, whereas the incomes derived from exploitation are more certain and quicker (He &Wong, 2004).

Duncan (1976) was the first scholar to introduce the concept of ambidexterity. Later, March (1991) added the terms exploitation and exploration, describing them as independent activities that include inherent trade-offs. Until today, March’s (1991) work has accumulated a high number of citations, a fact that shows that these concepts are worth pursuing and analyzing in order to conceive the full magnitude and essence of their influence (Wilden et al., 2018). In line with March’s research, Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) further developed the conceptualization of ambidexterity by introducing evolutionary and revolutionary change processes. These authors emphasized the structural separation between the two different types of activities. In the short-term, managers must continuously increase the fitness of strategy, structure, and culture (evolutionary change—exploitation), whereas in the long-term, they may be required to destroy the alignment that made their firms successful (revolutionary change—exploration).

Based on the above, He and Wong (2004: 483) suggested that ambidextrous firms are “capable of operating simultaneously to explore and exploit”. Lubatkin et al., (2006: 2) defined these organizations as “able of exploiting existing competencies as well as exploring new opportunities with equal dexterity”. With respect to the ambidexterity concept, March (1991) as well as Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) suggested that firms simultaneously pursuing exploitative and explorative orientations can achieve superior performance when compared to firms focusing on one at the expense of the other. Firms that mainly pursue exploitation achieve returns that are predictable but not necessarily sustainable; they may enhance their short-term performance, but that can result in a competence trap, as they may not be able to respond adequately to environmental changes. On the contrary, previous scholars have acknowledged that for firms to compete successfully in the long-term, they probably need to be able of pursing exploitation and exploration, with ambidexterity being a key driver in their long-term performance (Kassotaki, 2022). Therefore, firms must pursue an optimal mix of exploration and exploitation in order to remain competitive both in the short- and long-term (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; Junni et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2018). However, despite this broad consensus, the literature remains unclear about the extent to which ambidexterity involves a firm’s effort to match the magnitude of exploration and exploitation, or the challenge to increase the combined magnitude of both (Cao et al., 2009).

The balanced dimension of ambidexterity refers to the firm’s orientation towards exploitative or exploratory activities, while the combined dimension of ambidexterity is related to their mutual efforts (Cao et al., 2009; Raisch et al., 2009; Venugopal et al., 2020). In the balanced perspective, ambidexterity can be described as midpoint, or an optimal point on a continuum, with exploitation and exploration lying at the two ends. On the other hand, in the combined perspective, exploitation and exploration are considered independent activities, where their maximized level can produce a high degree of ambidexterity (Kassotaki, 2022; Fig. 1).

Source: Adapted from Kassotaki (2022, p. 11)

Measurement of organizational ambidexterity.

With regards to their measurement, the balanced ambidexterity can be operationalized as the absolute difference of exploration and exploitation (Cao et al., 2009; He & Wong, 2004), whereas the combined dimension of ambidexterity may be measured as a product (Cao et al., 2009; Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; He & Wong, 2004), or a sum of both (Lubatkin et al., 2006). Although this distinction is valuable, the discrepancy in how ambidexterity is operationalized difficults comparing the results across existing studies, particularly, to clarify if a firm should balance exploration and exploitation or maximize both (Cao et al., 2009).

Thus, recognizing the different ways that have been used to understand ambidexterity, we capture a more complete picture of the concept. Therefore, we unpack ambidexterity in one construct with four dimensions, which have been named exploitation, exploration, balanced ambidexterity, and combined ambidexterity. Distinguishing between these dimensions, at the conceptual level, allows providing a greater clarity about the construct, as well as to create the basis for hypothesizing and evaluating the independent and joint effects of exploitation and exploration on the clustered firms’ innovative performance.

2.2 Central tensions of ambidexterity: ambidexterity in clustered firms

According to Moore (1993), business ecosystems are an economic community supported by a foundation of interacting organizations and individuals. An analysis of a business ecosystem requires a well-defined notion of the environment and a distinction of the characteristics that make it conducive to business formation and growth. A significant number of researchers have approached this issue by identifying a set of factors describing the optimal environment for businesses. This work dates back to Marshall (1890) who emphasized that agglomeration economies provide benefits of co-location to local firms in the availability of skilled labor and knowledge. Later contributions on this field (e.g., Breschi & Malerba, 2001; Enright, 2003; Ethier & Markusen, 1996; Gordon & McCann, 2000) focused on agglomeration to entrepreneurship. These scholars addressed the potential advantages of entrepreneurial environments in terms of co-location, social embeddedness in a concentrated region, and value creation (Pitelis, 2012).

Porter (1998) provided a theoretical backbone for entrepreneurial ecosystems suggesting that, it is not just the endowment of resources or production factors influencing economic performance, but also their configuration or organization within the relevant space, that enhances economic performance. This author introduced the concept of clusters, which he described as geographical concentrations of interconnected firms, specialized suppliers, service providers, enterprises in related industries, and associated institutions (e.g., universities, standard agencies, trade associations) in a particular field, which compete but also cooperate. The main idea is that enhancing economic performance is not limited to the access to key resources but also depends on the location in a place characterized by a rich cluster of economic activity in the relevant industry. Porter’s seminal work contributed to establish that the organization of economic activity involving complementarities in production within a regional space would enhance performance, not only for the organizations involved in that particular cluster but also for the entire geographic unit of observation: a city, community, state, region, or even an entire country.

Our paper, therefore, responds to the calls from recent literature for a better understanding of how contextual conditions influence ambidexterity (e.g., Hughes et al., 2021; Lavie et al., 2010; Wolf et al., 2019), focusing on the firms’ external context. For most of firms, a particularly contextual factor is their local cluster (Jacob et al., 2022). Some authors even consider that clustered firms enjoy uniformly “asymmetric” competitive advantages compared with firms not operating in a cluster (Feldman, 1994; Porter, 1998). An industrial cluster enhances interactive learning through the proximity among clustered firms, spatially, socially, and cognitively (Boschma, 2005). Spatial proximity within a cluster reduces barriers to face-to-face interactions and increases exposure to knowledge externalities thereby contributing to learning and innovative outcomes (Von Hippel, 1994). Social proximity allows the development of trust-based relationships in the social networks established between clustered firms (Autant-Bernard et al., 2007; Zucker et al., 1998). Finally, cognitive proximity reflects the shared knowledge base which enhances the clustered firms’ ability to absorb new knowledge and reduces the uncertainty in the technology development process (Jacob et al., 2022).

Because of their features, industrial clusters can support firms’ optimization and management of resources conducive to innovation-related activities (Faridian et al., 2022; Fotso, 2022; Pucci et al., 2020; Töpfer et al., 2019), because the collaboration among clustered firms fosters knowledge and resources transfer for creating new products, processes, and technologies thereby accelerating their commercialization (Nishimura & Okamuro, 2016). Thus, industrial clusters are at the heart of innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems where local and regional elements shape the aggregate capabilities of local agents (Alvedalen & Boschma, 2017; Autio et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Pose & Ganau, 2022). This environment of innovative activity functions as a critical source of entrepreneurial opportunity and performance (Perugini, 2022; Radosevic & Yoruk, 2013). In this context, voluntary and involuntary knowledge spillovers take place, favoring open innovation strategies (Fischer et al., 2022). Again, interorganizational interactions are the key in these dynamics, as well as in the processes of resource allocation involving, directly or indirectly, communities of stakeholders involved with the entrepreneurial activity (Cao & Shi, 2021). This produces a sense of interdependence among actors, i.e., the entrepreneurial event becomes a systematic output rather than a decision of isolated individuals (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021). Hence, drawing on the above discussion, the following subsections focus on the role that both exploitation and exploration can play on entrepreneurial-, managerial-, and innovation-related tensions at the clustered firms’ level.

2.2.1 Managerial-related ambidexterity in clustered firms

The challenge of aligning long-term development of new competences and market fields via exploration with present revenue from an existing knowledge base through exploitation becomes obvious when we look to the situation from a resource-based perspective: a firm’s knowledge base, which is unique and difficult to imitate, constitutes a key competitive advantage (Grant & Baden-Fuller, 1995). In developing their knowledge base, firms can use internal and/or external knowledge sources (Zahra & George, 2002). The relative importance of each of these sources depends on the innovation strategy with respect to ambidexterity and has consequences for firms’ internal and external organization (Stettner & Lavie, 2014).

The implementation of ambidexterity requires a combination of organizational routines, resources, or capabilities that, to some extent, contradict each other: organizational efficiency (exploitation), on the one hand, and organizational flexibility (exploration), on the other (e.g., Adler et al., 1999; Raisch et al., 2009). In fact, exploitation and exploration are considered complex concepts because firms might gain from specializing in one or another (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004). For a long-term prosperous development, this would require firms specialized in exploitation to interact with their counterparts that, instead, pursue exploration and vice-versa– i.e., a division of labor. A plausible explanation for the difficulty of adopting both, at the same time, is that they require different organizational structures. According to some scholars (e.g., Boumgarden et al., 2012; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2008), exploration benefits from a decentralized and organic design, whereas successful exploitation environments are rather centralized and mechanistic. Most of firms usually devote their activities to exploiting existing knowledge and resources, which creates short-to medium-term profits, while only a small fraction of their effort goes into exploration (Wolf et al, 2019).

To address this issue, firms can try to “externalize” a part of the process in exploration. In this regard, Ferrary (2011) concluded that this specialization model describes the firm behavior regarding the use of new knowledge sources. Specifically, the author showed that Cisco Systems has been able to grow successfully, although it has specialized in exploitation. Because of its close ties to venture capital firms and start-ups in Silicon Valley, Cisco Systems integrated new knowledge by mergers and acquisitions of highly explorative start-ups. Nevertheless, some relevant activities stay within the firm: they correspond to monitoring new technologies and the competences needed to select between the different possibilities.

As the discussion above has shown, the external sources of knowledge and resources can be important both in exploitation and exploration of clustered firms. On the one hand, in managerial-related exploitation, they enable the individual firm to pursue goals within a specific domain by utilizing commonly created solutions in user-producer relations, or by providing the external expertise needed to refine a product. On the other hand, in managerial-related exploration, external sources are important for the creation of new ideas or for the development of common R&D projects that combine different tools under a new technological regime, as well as for the promotion of a creative environment that large firms can use as a “breeding manual” for new ideas that are followed by new ventures (Wolf et al., 2019).

2.2.2 Entrepreneurial-related ambidexterity in clustered firms

Recent research has shifted the focus from organizational-related ambidexterity to the individual level, in order to understand the psychological micro-foundations of ambidexterity (Schnellbächer & Heidenreich, 2020). According to Tushman and O’Reilly (1997), the literature has increasingly discussed internal processes for top managers that facilitate the implementation of structural and contextual ambidexterity. In other words, understanding how entrepreneurs shift between exploitation and exploration is the key to develop a theory about the paradoxical nature of ambidexterity as an individual behavioral construct. Based on this understanding, Bidmon and Boe-Lillegraven (2020) proposed a theoretical model in which switching from exploitation to exploration and vice-versa was associated with strong emotional reactions, such as, confusion, dissatisfaction, even anger and agitation, as well as displays of cognitive exhaustion such as appearing tired and having circular discussions. These reactions then manifested in behavioral displays of resistance whereby entrepreneurs often ignored the switching cue, or actively argued that they needed more time to focus on the current activity. This evidence suggested that ambidextrous switching in individuals is cognitively and emotionally taxing and, therefore, individuals tend to maintain one of the two activities (Klonek et al., 2021).

Making the analogy with the clustering literature, and drawing on previous studies (e.g., Bocquet & Mothe, 2015; Kauppila, 2007; Wolf et al., 2019), we look at the potential supportive role of industrial clusters on entrepreneurial-related ambidexterity and, therefore, we concentrate on the actor level. Accordingly, we define cluster management as a core organizational unit that provides their members with what they need. Through interorganizational collaboration, the cluster provides the necessary skills and processing abilities to support the acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation of knowledge (Zahra & George, 2002). Even though the core of the knowledge base lies within individual firms, cooperation activities play a key role for the development of internal knowledge and for long-term competitiveness. Thus, innovation usually results from an interorganizational process, with a division of labor regarding exploitation and exploration among enterprises, institutes, and universities inside the cluster (Ferrary & Granovetter, 2009; Porter, 1998).

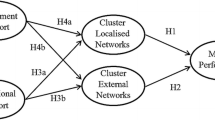

By addressing innovation strategic entrepreneurship’s tensions, we argue that exploration and exploitation have important roles on innovation production, resource allocation decisions, and entrepreneurial opportunities, because, in a network, ambidexterity may take two forms (Kauppila, 2007). First, based on Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) assumption of separating exploration and exploitation, clustered firms’ managers may specialize in one or another. If specialization occurs, cluster ambidexterity is achieved through the development of interorganizational relationships. Since local actors are unable to simultaneously pursue exploration and exploitation, clustered firms make the network ambidextrous by “(…) taking on different burdens with respect to exploitation and exploration” (Kauppila, 2007, p. 20) (Model 1; Fig. 2). Second, considering Gibson and Birkinshaw’s (2004) assumption that firms can embody ambidexterity, each clustered firm can be ambidextrous in order to internalize complementary knowledge derived from interorganizational relationships. This dual approach reflects the clustered firms’ ability to reconcile two apparently “opposite” activities, so “(…) the companies make each other ambidextrous by using the network” (Kauppila, 2007, p. 20) (Model 2; Fig. 2). In this view, employees and managers embody ambidexterity, which manifests at the organizational level (Kauppila, 2007). Thus, if each firm in the cluster is ambidextrous, the network is ambidextrous as well (Wolf et al., 2019).

2.2.3 Innovation-related ambidexterity in clustered firms

Some scholars (e.g., Gedajlovic et al., 2012; March, 1991) define innovation-related ambidexterity as a firm’s ability to balance the needs for exploitation and exploration simultaneously. For a firm, this requires managing the incremental improvement of existing products and processes (exploitation), while also engaging in the development of radical innovations (exploration) (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). Achieving innovation-related ambidexterity challenges firms to deal with a constant trade-off, aligning exploitation and exploration, which generates tensions (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004) that produce different levels of stress and pressure (Junni et al., 2015). However, given the clear patterns of positive short-term and long-term effects of ambidextrous behavior on performance (Soetanto & Jack, 2018; Vrontis et al., 2017), managing these tensions is of paramount importance for firms’ growth and survival. For innovative firms, this boils down to the basic problem of accomplishing sufficient exploitation of known options to secure current profits and, at the same time, to explore new options to safeguard future revenues (Wolf et al., 2019).

Industrial clusters constitute a unique context, providing structural mechanisms that are frequently associated with innovation (Zhang et al., 2019). To find out to what extent cluster management is valuable for ambidexterity, Bocquet and Mothe (2015) provided a case study of two French “Poles de Competitivé”. The authors collected information through semi-structured interviews and found that the mere geographical proximity between clustered firms is not enough to ensure knowledge exchange for exploitation and exploration. Specifically, Bocquet and Mothe (2015) showed that cluster organizations can influence innovation-related exploratory and exploitative efforts and, thus, contribute to the ambidexterity of the individual firms and the overall cluster, by stimulating their development in three ways: (1) at the project level, the cluster organizations can foster common R&D and innovation projects that either contribute to the further development of existing competencies within clustered firms (exploitation), or to the development of new capabilities to explore future possibilities (exploration); (2) at the actor level, the cluster organizations encourage the development of interorganizational relationships that clustered firms can use both to refine existing products/production processes (exploitation), or to look for new ways of doing things in order to differentiate themselves (exploration); and (3) at the cluster organization level, a common strategy can be pursued that either relates to the further development of existing technologies (exploitation), or with the creation of new routes for innovation (exploration).

Based on these considerations we argue that ambidexterity can function as the missing link between management, entrepreneurship, and innovation in several ways (Fig. 2). First, at the management level, through the interorganizational relationships developed among different actors, clustered firms can acquire new resources (exploration), and/or adapt the existing ones (exploitation) to succeed in their operations. Second, at the entrepreneurship level, the central tensions of ambidexterity are considered the micro-foundations of entrepreneurial opportunities (Schnellbächer & Heidenreich, 2020; Vrontis et al., 2017). To address this issue, we analyze the cluster interorganizational relationships at the national and international level. Clustered firms’ positioning in international networks is a way for decision-makers to diversify the risk management corresponding to an entrepreneurial process. Specifically, our measure of ambidexterity reflects its international decisions, since clustered firms can exploit entrepreneurial opportunities by prioritizing the achievement of efficiency and economies of scale through internationalization (exploitation), and/or the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities to increase the depth and breadth of the internationalization process (exploration). In this assumption, several entrepreneurial organizations can be born (new clustered firms), and/or been rejuvenated (established clustered firms with an entrepreneurial orientation), by building this capacity via exploration and exploitation. Third, at the innovation level, based on the knowledge flows between several agents, clustered firms can prioritize the development of new products/services (exploration), and/or the refinement of the existing ones (exploitation), producing radical and incremental innovations.

2.3 Hypotheses development

In the “open innovation” model, since firms do not always have the knowledge required for product innovation, they continuously search for new knowledge provided by external sources (Zhang et al., 2019). Even though the core knowledge base is available inside the firm, cooperation activities play a key role on the development of internal knowledge and long-term competitiveness (Wolf et al., 2019), that is, an important interface between industrial association and entrepreneurship encompasses innovation (Audretsch & Link, 2019).

The topic of industrial clusters and their innovative capabilities has been extensively studied in the literature (e.g., Bell, 2005; Lai et al., 2014; Speldekamp et al., 2020). One explanation for the geographical concentration of innovation is that the knowledge developed within industrial clusters circulates more easily due to interorganizational relationships (Dahl & Pedersen, 2004), which means their members innovate more and grow faster (Baptista & Swann, 1998). Considering its dynamics, a cluster provides a set of resources that support innovative capacity (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996), so clustered firms are considered more innovative than their counterparts because they benefit from agglomeration economies (e.g., the ability to exploit collective knowledge), and have access to network-based effects that enhance social interaction (Harrison, 1992).

In this way, firms attempt to cooperate with other market players to acquire resources and engage in cross-organizational learning (Yli-Renko et al., 2001). Previous research has emphasized that the development of such networks allows knowledge creation and transfer, which has a leverage effect on the innovative capacity (Wu & Wu, 2019). Based on this understanding, we argue that the knowledge flows derived from the cluster interorganizational relationships acts as a “helping hand” in the introduction of several types of innovation and, therefore, increase the clustered firms’ innovative performance. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 1

As firms within industrial clusters engage in interorganizational relationships, the higher is their innovative performance.

The extant literature establishes that it is easier for clustered firms to create and accumulate knowledge due to the constant interactions with several actors (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996; Marco-Lajara et al., 2022). However, it is not just the geographical proximity, but also the cultural similarity, that facilitates interactive learning and a propensity to share knowledge, based on external collaboration. With regards to the cluster shared knowledge, Asheim and Coenen (2005) introduced the distinction between regional knowledge exploitation and regional knowledge generation (exploration). This corresponds to a case of alliance ambidexterity (Sun & Lo, 2014) or interorganizational ambidexterity (Kauppila, 2015), implying a simultaneous development of exploration and exploitation supported by interorganizational relationships (Marco-Lajara et al., 2022).

The cluster literature has shown that clustered firms use a mixture of intra- and extra-cluster ties for innovation development (Bathelt, 2005). According to Jacob et al. (2022), intra-cluster ties are geographically proximate relationships formed within the cluster, whereas extra-cluster ties derive not from geographical proximity, but from the purposeful, and even risky, cooperation that span the boundary and geographic location of the cluster. Accordingly, intra-cluster ties with geographically proximate partners facilitate frequent and repeated knowledge sharing, showing that it is beneficial for exploiting existing capabilities (McEvily & Zaheer, 1999), while extra-cluster ties bring in knowledge elements that are different from those available within the cluster, allowing firms to continuously rejuvenate their knowledge base (exploration) (Boschma & Ter Wal, 2007; Maskell et al., 2006).

Despite being more costly to firms, to acquire knowledge from distant external sources than to learn from proximate sources, the ideas, knowledge, and information acquired from geographically distant sources are crucial for avoiding excessive exploitation and for promoting exploration (Jacob et al., 2022). Overall, by enabling access to distant knowledge sources, extra-cluster ties help firms to prevent lock-in effects associated with local embeddedness (Boschma & Ter Wal, 2007; Maskell et al., 2006). Particularly, extra-cluster ties can grant managers with varied experiences, mental models, and information that may give them the ability to pursue exploration, side by side with exploitation through intra-cluster ties (Jacob et al., 2022).

As the discussion above has shown, networking capabilities positively relate to the exploitation of market opportunities and the exploration of knowledge-intensive products (Mort & Weewardena, 2006). The constant communication between different partners encourages collaboration and supports networked firms to share perspectives towards exploratory and exploitative activities (Tempelaar et al., 2010). Therefore, networking capabilities may contribute to the development of exploitation in terms of replicating existing ties, but also to enhance exploration leading to the transfer of heterogeneous experiences, knowledge, and new skills (Pinho & Prange, 2016). Based on these arguments, we suggest that cluster interorganizational relationships provide the knowledge that firms need to effectively allocate resources in terms of exploration (experimentation of new activities) or exploitation (extension of existing activities). This discussion leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a

The development of interorganizational relationships has a positive impact on the clustered firms’ ability to pursue an exploitative orientation.

Hypothesis 2b

The development of interorganizational relationships has a positive impact on the clustered firms’ ability to pursue an explorative orientation.

According to Töpfer et al. (2019), the cluster innovation policy is effective in initiating new cooperation between local actors and in intensifying existing linkages. Therefore, the contribution of industrial clusters to ambidexterity can be highlighted by two different characteristics. The first is supported on their interorganizational relationships because exploitation and exploration are two elements of industrial cooperation (Marco-Lajara et al., 2022; Parmigiani & Rivera-Santos, 2011). Marco-Lajara et al. (2022) pointed out that exploitation in clustered networks can be described as a voluntary collaboration agreement to execute knowledge, tasks, functions, or activities where the emphasis is put on using and expanding existing knowledge, while exploration in clustered networks represents a voluntary agreement to create new knowledge, tasks, functions, or activities. On the other hand, the second feature relates to the fact that firm-level characteristics may not fully explain organizational ambidexterity (Marco-Lajara et al., 2022), because firms have few mechanisms to avoid harmful conflicts between exploitation and exploration (Kang et al., 2007), suggesting that a balanced ambidexterity might be more effective and it can be created by using the networks within and across firms boundaries (Ossenbrink et al., 2019).

When the top management team engages in informal and formal networking and achieves a perceptible degree of cohesiveness, it is better enabled to negotiate the distribution of resources between the firm’s existing exploitative and its new explorative pursuits (Lax & Sebenius, 1987). With enhanced information exchange, the top management team can combine diverse opinions on common mental platforms and distribute the paradoxical strategic demands of resources, time, and personnel allocation to achieve a balanced dimension of ambidexterity (Martin et al., 2019; Raisch et al., 2009; Smith & Tushman, 2005). Likewise, when the top management team makes collective decisions, they are striving towards a common mental platform that balances several vested functional interests (Venugopal et al., 2020). With joint decisions, managers are aware of all the strategic decisions available to the firm, becoming easier to develop the paradoxical cognitive processes to reach an optimal distribution of resources—i.e., the combined dimension of ambidexterity (Smith & Tushman, 2005).

Within this research stream, several scholars (e.g., Kauppila, 2015; Lavie et al., 2011; Úbeda-García et al., 2020) also argued that interorganizational relationships play a vital role in strengthening and complementing firms’ exploitation and exploration activities. Enhanced collaboration at the organizational level enables a firm to make integrative decisions that take advantage of the inter-operable nature of tasks and resources (Venugopal et al., 2020). The task dimension of collaborative top management teams fosters the firm’s ability to integrate and combine paradoxical ambidexterity pursuits (Smith & Tushman, 2005). Drawing on the extensive networks, firms receive several resources to evaluate, refine, and develop new ideas, enlarging “the quantity and quality of feedback […] and the range of options for combining exploitation and exploration” (Heavey et al., 2015, p. 204). In conclusion, knowledge creation and sharing are easier for clustered firms, due to geographical proximity and cultural similarity, which facilitates the establishment of cooperative relationships that, in turn, support enterprises in balancing and combining exploratory and exploitative activities. On this basis, we postulate:

Hypothesis 2c

The development of interorganizational relationships has a positive impact on the clustered firms’ ability to balance explorative and exploitative orientations.

Hypothesis 2d

The development of interorganizational relationships has a positive impact on the clustered firms’ ability to combine explorative and exploitative orientations.

For long-term success firms need to consider dual approaches to execute innovation (Duncan, 1976). Ambidextrous organizations stand out at exploiting resources to incremental innovations and at exploring new opportunities to boost radical innovations (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009). Hence, studies focusing on ambidexterity have found that both exploitation and exploration are essential for new product development (Sheremata, 2000). In investigating how exploration and exploitation affect firm’s performance, the existing literature makes the following inferences: (1) the two orientations have a positive effect on performance (Junni et al., 2013; Mathias et al., 2018), and (2) the influence of exploitation and exploration on performance is context-dependent, varying according to organizational (Belderbos et al., 2010; Mathias et al., 2018) and environmental (Gatti et al., 2015; Luger et al., 2018) conditions.

Exploitative and exploratory orientations require different learning mechanisms, resources, and routines (March, 1991), but both can be beneficial for innovation. On the one hand, exploration enhances innovative performance by creating new opportunities and enabling firms to target new markets (He & Wong, 2004; Mueller et al., 2013). On the other hand, exploitation can also improve innovative performance through the refinement and variance reduction and further penetration of the firm’s existing markets (He & Wong, 2004; Mueller et al., 2013). Building on this discussion, we argue that in clustered firms, unable to pursue simultaneous exploration and exploitation regardless of the orientation that they choose prioritize, increasingly levels of innovation can be experimented. Accordingly, we outline:

Hypothesis 3a

For clustered firms pursuing an exploitative orientation, the innovative performance is higher.

Hypothesis 3b

For clustered firms pursuing an explorative orientation, the innovative performance is higher.

Additionally, other studies suggest that a combination of exploitation and exploration allows benefiting from improved learning and innovation (e.g., Holmqvist, 2004; Katila & Ahuja, 2002). Prominent theorizing suggests that ambidexterity generally leads to better performance than a focus on either exploration or exploitation (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996). Thus, the organizational ambidexterity can be reached by combining and balancing both orientations. The combined dimension of ambidexterity allows firms to harvest synergies of exploration and exploitation, while the balanced dimension of ambidexterity protects firms against the adverse effects of over-exploration and over-exploitation (Cao et al., 2009; He & Wong, 2004; March, 1991). We, therefore, reason that a closer match between exploration and exploitation, as well as an increased combined magnitude of both, improves firm’s performance (March, 1991).

On the one hand, when the magnitude of exploitation exceeds exploration, the firm is likely to be subject to a risk of obsolescence (Cao et al., 2009). Firms exposed to this type of risk may benefit from short-term success derived from exploiting existing products and markets, but this success will be unsustainable in the long-term due to technological change and the markets dynamism (Tushman & Anderson, 1986). On the other hand, when the magnitude of exploration exceeds exploitation, it increases the risk of failure because firms may be unable to appropriate returns from its costly search and experimentation activities (He & Wong, 2004). Building on this logic, we argue that a closer match between exploration and exploitation (i.e., balanced ambidexterity) allows to avoid or to better manage these risks.

Conversely, the central idea of combined ambidexterity is that exploration and exploitation are not necessarily in competition, and both can take place in complementary domains (Gupta et al., 2006). A high degree of exploitation can make the firm more efficient in exploring new knowledge and on developing resources that support the development of new products, while a proficiency in exploration (e.g., in one product or technological domain) can enhance exploitative efforts in a complementary domain (Cao et al., 2009). In summary, we propose that because organizational learning and resources can often be effectively leveraged across both types of orientations, exploration and exploitation might complement each other (i.e., combined ambidexterity) and lead to higher levels of innovation. Therefore:

Hypothesis 3c

For clustered firms balancing explorative and exploitative orientations, the innovative performance is higher.

Hypothesis 3d

For clustered firms combining explorative and exploitative orientations, the innovative performance is higher.

Based on the above, we developed a research model to test the innovation strategic entrepreneurship’s tensions, by considering the clustered firms’ ability or inability to simultaneously pursue both exploration and exploitation (Fig. 3).

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample and data

Firms belonging to the manufacturing and service sectors are the population under analysis. The first step of data collection was to identify the Portuguese industrial clusters. For this purpose, we consulted the IAPMEI website (Agency for Competitiveness and Innovation), obtaining a total number of 19 clusters (IAPMEI, 2019). Then, the cluster management organizationsFootnote 3 were contacted in order to provide the following information: (1) classification of the clustered firms’ economic activities (NACE codes), (2) geographical location of the cluster, (3) identification of other institutions (e.g., universities, research centers, training organizations, among others) that may belong to the cluster, and (4) membership conditions. The initial contact was made via email and, later, via telephone, to reinforce the request for the participation in the study conducted between October 2019 and February 2020. At the end of data collection, 17 responses were considered valid (89.5% response rate). The statistical data was gathered using three questionsFootnote 4 from the survey sent to cluster management organizations, and CIS database was selected to collect quantitative information. Analyzing the 17 responses, we concluded that only 10 provided all information requested. However, 6 did not match with the firm’s NACE codes available on CIS database and, for this reason, they were excluded. Thus, our analysis focused on 4 clusters: (1) Footwear and Fashion, (2) Textile—Technology and Fashion, (3) Petrochemical, Industrial Chemistry and Refining, and (4) Automotive.

Since our target variable is the firms’ innovative performance, the CIS instrument was selected to collect quantitative information because it provides useful data on how firms interrelate with the external environment in order to successfully develop innovation projects. Developed under the guidelines of the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2005), the survey is the main statistical instrument to monitor the Europe’s progress in terms of innovation. This survey aims to collect data on innovation understood in a broader perspective rather than exclusively examining the invention process. Following the Eurostat recommendations, the Portuguese version directly collects information on product, process, organizational, and marketing innovations. This dataset includes the period between 2010 and 2012, contemplating firms with ten or more employees operating in different sectors. The CIS questionnaire was available between 3rd June 2013 and 14th March 2014 (DGEEC, 2014). Based on census combination for larger firms and random sampling for others, the survey consisted of 9423 enterprises. In the corrected sample of 7995 companies, 6840 valid answers were obtained (86% response rate) (DGEEC, 2014). Since our purpose is to evaluate how ambidexterity can help clustered firms to increase their innovative performance, considering the role played by interorganizational relationships, our sample includes the enterprises that can belong to the four clusters. Moreover, as organizational ambidexterity also comprises an international dimension, we selected firms that had, at least, one year of international sales. At the date of data extraction (July 2020), 1467 firms met all the above criteria (Table 1).

In order to examine the sample, we performed descriptive and correlation analysis in IBM SPSS statistics software version 28. As shown in Table 2, the sample is relatively balanced between manufacturing (48.88%) and service sectors (51.12%). Following the Eurostat recommendations (Decree-Law No. 98/2015), most of the enterprises are classified as SMEs (81.73%). The correlations are generally low to moderate indicating a low risk of collinearity issues (Table 3). However, it is important to highlight a strong positive correlation between balanced ambidexterity and exploration (0.771**), as well as between combined ambidexterity and exploration (0.904**), since they can be considered measuring the same domain (i.e., ambidexterity). To address this issue, we evaluated the potential common method bias through a full collinearity approach. According to Kock (2015), the occurrence of variance inflation factor (VIF) values above 3.3 is an indication of multicollinearity. As all VIF values are below to the recommended threshold (Table 6), the entire dataset can be considered free from multicollinearity.

3.2 Variables and statistical procedure

A structural equation model was used to test the hypotheses in SmartPLS software version 3.3.3 (Ringle et al., 2015). The use of PLS-SEM is appropriate when the research features one or more of the following circumstances (Hair et al., 2019): (1) the observed variables have some degree of non-reliability, (2) the data come from non-normal distributions, (3) secondary data are used, and (4) the sample size is large. Considering the sample size (n = 1467), the variables included on the analysis do not follow a normal distribution. However, in a limited number of situations, non-normal data may also influence the PLS-SEM results (Hair et al., 2019). The use of bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrapping handles this issue, as it corrects the confidence intervals for skewness (Efron, 1987). Following these guidelines, we adopted the BCa bootstrapping in order to adjust the data for potential bias.

The CIS questionnaire used in this study is divided into twelve sections. There are four sections accessing product, process, organizational, and marketing innovations, and one section accessing the strategies used by firms to accomplish their goals (in terms of ambidexterity). To evaluate the firms’ innovative performanceFootnote 5 (target variable), we adopted scales validated in previous research (e.g., Gupta, 2008; Leifer et al., 2000; OECD, 2005) including a typology of product, process, organizational, and marketing innovations. Following extant literature (e.g., Gupta, 2008; Leifer et al., 2000), innovation is understood as the development of something new (radical innovation) and/or the gradual improvement of something existing (incremental innovation). Accordingly, it is argued that both innovations are not mutually exclusively and may be used as complementary actions to deal with the external demand. For the purpose of this research, we used any type of innovation (radical or incremental).

With regards to network clustering (explanatory variable), to identify the entities that may belong to industrial clusters we adopted the NACE codes provided by the cluster management organizations (Baptista & Swann, 1998). Focusing on the network dimension of industrial clusters (e.g., Lai et al., 2014), the interorganizational relationships were operationalized considering two dimensions: (a) national networks that embrace the relationships developed on the domestic market, and (b) international networks representing the interactions outside the home country (Musteen et al., 2010; Varma et al., 2016).

On the other hand, the measurement of organizational ambidexterity (mediating variable) is grounded on the theoretical definition of exploratory and exploitative orientations (Lubatkin et al., 2006; March, 1991), using two different items to measure each of them (see Table 7 in Appendix). On this basis, balanced ambidexterityFootnote 6 refers to the relative magnitude of exploitation and exploration and it was computed as the absolute difference between exploration and exploitation, whereas combined ambidexterity was obtained through the multiplicative interaction of exploration and exploitation (e.g., Cao et al., 2009; He & Wong, 2004). We followed the continuity and orthogonality logics (Faridian et al., 2022), where the balanced dimension of ambidexterity suggests a trade-off between exploration and exploitation and, thus, it is associated with the continuity logic, while the combined dimension of ambidexterity suggests a complementary effect between both and, hence, it is related to the orthogonality logic (see Fig. 1). It is worth noting that, we mean-centered the exploratory and exploitative scales before obtaining their product to reduce potential collinearity issues (Cao et al., 2009). Finally, consistent with the academic literature (e.g., Bach et al., 2015; Baum et al., 2001; Tourigny & Le, 2004), this study also controls firm’s size, public financial support, and information sources for innovation (see Table 7 in Appendix).

Before estimating the models, we examined the potential common method variance (CMV) in our data. According to the Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2012), if CMV exists, a factor would emerge from factor analysis explaining most of the variance. The Principal Component Analysis revealed 22 distinct factors capturing 65.415% of the total variance, with the main factor only accounting for 21.109%. Since none of the factors explained more that 50% of the variance, CMV was not a relevant issue.

4 Results

4.1 Stage 1: Measurement model evaluation

The evaluation of the PLS-SEM begins with an assessment of the reflective measurement models. Overall, the six constructs meet the relevant assessment criteria (Table 4). The rule to retain reflective indicators is based on outer loadings, that are above 0.6 indicating a sufficient level of reliability (Hair et al., 2013). Furthermore, all AVE values are higher than 0.50 which reveals convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Composite reliability (CR) displays values that range between 0.782 and 0.895, being above of the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2019). The Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) suggests that the constructs exploration, information sources, innovative performance and exploitation are acceptable measures, whereas network clustering and public financial support are inadmissible measures (Hair et al., 2019). Moreover, almost all ρA values fulfilled the threshold of 0.707 (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015). Overall, these results suggest that the latent variables exhibit a sufficient level of internal consistency reliability.

The discriminant validity was accessed by using the hetero-trait mono-trait ratio (HTMT) (Henseler et al., 2015). All the results are below to the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Kline, 2011) (Table 5). Additionally, a bootstrap over 5000 samples was conducted with no sign changes in the resampling. We used a one-tailed test at 0.05 significance level (i.e., 95% confidence interval). The outcomes reveal that the HTMT values are significantly different from 1, which means that discriminant validity has been established between all pairs of constructs. The reflective model results, therefore, suggest that the measures display satisfactory levels of reliability and validity, which means that we can proceed with the structural model evaluation.

4.2 Stage 2: Structural model evaluation

The algebraic sign, magnitude, and significance of beta estimates and the R2 values allow an evaluation of the structural model (Table 6, Fig. 4). The adjusted R2 of innovative performance corresponds to 14.2% in model 1 and 13.7% in model 2. The effect size (f2) complements the R2 assessment, considering the relative impact of an exogenous variable on the endogenous construct through the changes in R2 values. According to Cohen (1988), f2 values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively. The highest f2 effect sizes occur for the relationships Exploration → Innovative Performance, Firm’s Size → Innovative Performance, and Information Sources → Innovative Performance. The overall approximate model fits (SRMR) are below the recommended threshold of 0.08 (Henseler et al., 2014), being smaller than their corresponding 95% and 99% quantiles (Henseler et al., 2016), which suggests the existence of a good fit.

In both models, we found as firms engage in interorganizational relationships, they improve innovative performance (H1: β = 0.056; p < 0.05), which supports hypothesis 1. By analyzing the results of model 1, we also conclude that the development of interorganizational relationships positively influences the clustered firms’ ability to pursue an explorative orientation (H2b: β = 0.061; p < 0.005), but they do not reveal a significant effect in the adoption of an exploitative orientation (H2a: β = − 0.013; p = 0.341). This evidence lends support to hypothesis 2b, but not for hypothesis 2a. Similarly, the findings indicate a positive relationship between exploration and innovation (H3b: β = 0.169; p < 0.001), but the impact of exploitation in the clustered firms’ innovative performance is not significant (H3a: β = 0.018; p = 0.234). These results validate the theoretical prediction inherent to hypothesis 3b, but not to hypothesis 3a.

Regarding the results of model 2, we found that the development of interorganizational relationships do not influence the clustered firms’ ability to combine explorative and exploitative orientations (H2d: β = 0.042; p = 0.277), which does not support hypothesis 2d. An interesting finding is that the interorganizational collaboration leads clustered firms to increase the absolute difference between exploration and exploitation, resulting in an imbalanced ambidexterity (H2c: β = 0.065; p < 0.01). This outcome is opposite to our theoretical prediction, so hypothesis 2c was not validated. With regards to the effect of ambidexterity on innovation, we found that clustered firms combining explorative and exploitative orientations reveal a higher innovative performance (H3d: β = 0.118; p < 0.001), but it is the imbalanced ambidexterity—i.e., a higher absolute difference between exploration and exploitation—that leads to increased levels of innovation in agglomerated firms (H3c: β = 0.064; p < 0.05). The empirical evidence, therefore, lends support to hypothesis 3d, but not to hypothesis 3c.

Concerning the control variables, firm’s size (Model 1: β = 0.177; p < 0.001; Model 2: β = 0.179; p < 0.001), and information sources (Model 1: β = 0.196; p < 0.001; Model 2: β = 0.200; p < 0.001) positively influence innovative performance, which means that the increase in the number of employees and the use of different information sources leads to a higher innovation in clustered firms. Conversely, in our sample, the public financial support does not have a statistically significant effect on innovative performance (Model 1: β = 0.010; p = 0.360; Model 2: β = 0.012; p = 0.377).

The indirect effects were also specified and tested (Table 6). When exploration and exploitation are introduced as mediating variables in model 1, the direct effect of network clustering, and the indirect impact of explorative orientation on innovative performance are both statistically significant. However, despite the direct of network clustering on innovation, the indirect effect of exploitation is non-significant. This means that exploration partially mediates the influence of interorganizational relationships on the clustered firms’ innovative performance, but exploitation does not. In addition, when introducing balanced and combined ambidexterity as mediators in model 2, we found that, although network clustering has a direct positive impact on innovation, the indirect effects of both dimensions were not statistically significant. This suggests that neither balanced ambidexterity nor combined ambidexterity mediate the relationship between interorganizational relationships and innovative performance in clustered firms.

4.3 Robustness checks

We ran additional tests to examine the robustness of our findings. First, we analyzed whether there was any reverse causality between variables by running the Park and Gupta’s (2012) Gaussian copula test. In model 1, considering innovative performance predictor variables as potentially endogenous they revealed non-significant copulas of 0.031 for network clustering (p = 0.867), 0.222 for exploitation (p = 0.101), 0.027 for exploration (p = 0.302), − 0.052 for firm’s size (p = 0.769), − 0.011 for public financial support (p = 0.698) and 0.010 for information sources (p = 0.751). In model 2, we also observed non-significant copulas of 0.021 for balanced ambidexterity (p = 0.293) and 0.028 for combined ambidexterity (p = 0.876), obtaining similar results for the remaining variables. Further, we examined all other combinations of Gaussian copulas, and none was statistically significant (i.e., p values were higher than the significance level of 5%). According to Hult et al. (2018), these results suggest that reverse causality does not seem to be an issue in our study. Second, we tested our findings for potential nonlinearities in the structural models conducting the Ramsey’s test (1969) on the latent variables scores. A significant value in any of the partial regressions indicates a potential nonlinear effect—quadratic or cubic (Hair et al., 2019). The results of the Ramsey’s test revealed that the partial regression of the predictor variables on innovative performance were not subject to nonlinearities (Model 1: F (6, 1456) = 0.581, p = 0.625; Model 2: F (6, 1456) = 1.542, p = 0.204), offering evidence of the linear effect’s robustness. Third, we carried out additional analyses with alternative measures for innovative performance. Specifically, we introduced the sum of the expenditures for all types of innovation activities as a measure of innovation (in-house R&D; external R&D; acquisition of machinery, equipment, software, and buildings; acquisition of existing knowledge from other enterprises or organizations; other innovation activities including design, training, and marketing). The resulting estimates exhibit patterns of significance similar to those reported in Table 6. Thus, all the additional estimates provide support for the robustness of our results.

5 Discussion and implications

In this paper, we have proposed a conceptual model to explore the influence of stakeholders and other cluster agents in the response of ambidextrous organizations to the challenges raised by environmental changes. Some studies have been looking for the role of clusters on the achievement of ambidexterity in individual firms (e.g., Bocquet & Mothe, 2015; Kauppila, 2007; Wolf et al., 2019). The organizational ambidexterity at the cluster level can have different meanings, which we address in our study: interorganizational relationships can contribute to innovation of individual firms by promoting exploration and exploitation. As firms closely cooperate in a cluster, their patterns of ambidexterity might also influence the degree of cluster ambidexterity. Cluster management organizations, acting as service providers, react to the specific demands of its “customers” being able to support firms to realize their ambidexterity strategies.

Our empirical analysis of 1467 firms contributes to this research stream and explores the influence of interorganizational relationships in the innovative performance, by considering the role of exploitation, exploration, balanced ambidexterity, and combined ambidexterity in clustered firms. In both models, clustered firms use cooperation for pursuing radical and incremental innovations, which is consistent with previous findings (Ferrary & Granovetter, 2009; Speldekamp et al., 2020; Wolf et al., 2019). The empirical evidence suggests that these firms search for new ideas within the cluster and use cluster cooperation in looking for new and/or improved products and services, corresponding to a way of dealing with the innovation management’s tensions that arise at the firm level (Raisch et al., 2009).

In model 1, we also found that network clustering has a positive impact on exploration, but a non-significant effect on exploitation. These outcomes reveal that the establishment of interorganizational relationships increases the firms’ willingness to pursue an explorative orientation, corroborating previous findings (e.g., Mort & Weerawardena, 2006; Pinho & Prange, 2016; Tempelaar et al., 2010). Clustered firms use cooperation for achieving exploration, so the benefits of cluster services are rather perceived by enterprises with activities that relate with this orientation. Such firms require cluster management services—e.g., public relations, consulting in terms of R&D funding, and networking with national and international actors—to help them scanning the external environment for new technological possibilities (Wolf et al., 2019). Similarly, the findings indicate a positive relationship between exploration and innovative performance, but the influence of exploitation on innovation is not significant. These results are consistent with previous works finding that industrial clusters, where a lot of firms are agglomerated and interacting with each other, have a positive impact on exploratory efforts and innovation (He & Wong, 2004; Lavie et al., 2011; Mueller et al., 2013). The relevance of the results is not only related with the possibility to access the resources and knowledge of other organizations inside the cluster, but also because it helps clustered firms to solve internal tensions between exploration and exploitation (Kang et al., 2007). At the entrepreneurial level, since exploration is measured as the development of new markets within and outside Europe, the integration of the decision-makers in clustered networks can function as way to diversify the management of risk in terms of internationalization, which can result in a launch of a new business and /or the renewal of the existing one (Liu et al., 2022).

Contrary to our expectations, the results of model 2 show that the greater establishment of network relationships, the lower is the balanced ambidexterity. In fact, a t-test of paired samples yielded a significant difference, showing that exploitation is higher than exploration (mean difference(Explore – Exploit) = − 1.11, t-value = − 21.804 significant at p value < 0.001). Since 81.73% of our sample is composed by SMEs, a plausible explanation relates to the fact that SMEs generally face internal constraints in terms of managerial experience, the available time to manage both orientations, and limitations in accessing to capital, talent, and resources (Ebben & Johnson, 2005). This restricts the chances to allocate resources to the exploration of new activities and, thus, achieve a closer magnitude between both orientations. Although belonging to industrial clusters could possibly alleviate exploitation-exploration tensions, the fact is that SMEs managers tend to consider exploration to be a more complex phenomenon than exploitation (Marín-Idárraga et al., 2016), requiring more time to produce a result. This lag in results leads managers to prefer exploitation rather than exploration, at least, in a timeframe of three years. Indeed, the focus on exploitation can be the appropriate response to the strong pressures on efficiency and prices that firms face in the short-term (Cao et al., 2009), as managers have better conditions to clearly understand extant knowledge, resources, and capabilities by using them repeatedly (Kristal et al., 2010). However, although in the short-term clustered firms may benefit from exploitation, such effect can become negative on the long-term (Dolz et al., 2019), being essential to invest on exploration to ensure differentiation. As argued by Levinthal and March (1993: 105), “the basic problem confronting an organization is to engage in sufficient exploitation to ensure its current viability and, at the same time, to devote enough energy to exploration to ensure its future viability”.

With regards to the effect of balanced and combined ambidexterity on innovation, we found that a higher absolute difference between exploration and exploitation (i.e., imbalanced ambidexterity) leads to a better innovative performance, which is somewhat an unexpected finding. More specifically, when the clustered firm exploitation exceeds its exploration, the company enjoys short-term success derived from exploiting new and existing products, but this success may be temporary, when confronted with technological and market changes (Tushman & Anderson, 1986). Moreover, a greater level of combined ambidexterity positively influences clustered firms’ innovation. The central idea of combined ambidexterity is that exploitation and exploration may be complementary activities, without necessarily compete for the same resources (Gupta et al., 2006). Our outcomes suggest that the organizational knowledge can be effectively leveraged towards both dimensions (i.e., exploitation and exploration), enhancing innovative performance. Taken together, these results indicate that (im)balanced and combined ambidexterity are two distinct dimensions that contribute to innovation. Our findings provide an interesting discussion, supporting the idea that exploration and exploitation are complementary (Marín-Idárraga et al., 2016; Prange & Verdier, 2011), that both are central to a firms’ development (He & Wong, 2004; Kristal et al., 2010), and have a positive impact on organizational performance (Peng & Lin, 2021). However, our measure of innovative performance was circumscribed to a timeframe of three years, so future investigations should include metrics oriented to the long-term to validate these findings.

In light with the above findings, we extended our discussion to a higher level of abstraction to shed light on how ambidexterity can function as the missing link between management, entrepreneurship, and innovation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to address this issue at the cluster level. To date, only the study conducted by Akulava and Guerrero (2022) tried to unveil the “black box” connecting the three research fields, however, not in agglomeration contexts, by investigating the balanced causal-effectual reasoning (entrepreneurial ambidexterity) adopted during a balanced exploitation-exploration process to achieve the highest innovation outcomes (innovation ambidexterity), through a balanced gender managerial decision-making style (managerial ambidexterity).

The empirical evidence has shown that, when clustered firms are unable to simultaneously pursue both exploitation and exploration (Model 1; Fig. 4), the explorative orientation stands out allowing to use the interorganizational relationships in several ways (Wolf et al., 2019): (1) to create new ideas, (2) to develop common R&D projects, and/or (3) to promote a creative environment where large firms can reproduce such ideas that, in turn, are adopted by new ventures within the cluster (managerial-related exploration). This explorative resource allocation will, therefore, foster the development of new routes for innovation (Colombo et al., 2015), resulting in higher levels of innovative performance (innovation-related exploration). In this case, clustered firms specialize in exploratory activities (Kauppila, 2007; Wolf et al., 2019), which means that the explorative orientation, at the cluster level, is achieved because the local actors make the interorganizational network explorative (entrepreneurial-related exploration).

On the other hand, when clustered firms are able to, simultaneously, pursue both exploitation and exploration (Model 2; Fig. 4), either by combining or (im)balancing both orientations, they can use the interorganizational relationships to adopt common created solutions in user-producer relations (managerial-related exploitation), while, at the same time, they may also resort to external knowledge sources to produce new ideas that allow an effective resource allocation decision (managerial-related exploration). In this situation, clustered firms adopt an ambidextrous resource allocation to achieve their organizational goals (managerial-related ambidexterity), depending on the situation to which they are confronted (Wolf et al., 2019). By following this type of managerial orientation, clustered firms are able to refine existing products and/or production processes, as well as to look for new ways of doing things in order to differentiate themselves (innovation-related ambidexterity). This is consistent with previous studies claiming that industrial clusters can support firms in the optimization process of the management of resources conducive to innovation activities (e.g., Faridian et al., 2022; Fotso, 2022; Pucci et al., 2020; Töpfer et al., 2019), which is linked to the idea of innovation-related ambidexterity. In this situation, each clustered firm is ambidextrous in order to internalize complementary knowledge and resources stemming from the interorganizational relationships within the cluster. This dual approach reflects clustered firms’ ability to reconcile two apparently contradictory activities, therefore, the firms make each other ambidextrous by using the network within the cluster (Kauppila, 2007; Wolf et al., 2019) (entrepreneurial-related ambidexterity).