Abstract

The South Korean government provided policy levers for technology transfer by establishing the Technology Transfer Promotion Act in 2000. It also implemented a technology transfer promotion plan based on this law. Along with the law’s enactment, the Korean government required the establishment of technology licensing offices (TLOs) for national and public universities. Although this policy led to the quantitative expansion of TLOs, it did not result in qualitative growth. The Korean government implemented a supplementary program to support the leading TLOs’ labor and business expenses. In the current work, the author questions if the program had a significant effect on the performance of TLOs. I analyze the policy effect on the performance of TLOs, as measured by royalty income or the number of technology transfer contracts. In particular, the heterogeneous effect is examined by using quantile regression applied to publicly available university panel data from 2007 to 2015. The results corroborate that the program had a significant impact only on the lower 10% quantile. The government also provides programs for marketing, consulting, and manpower training. However, the policy only focuses on financial support, and the support provided to each university is uniform. In addition, results suggest that the support policy must be diversified based on the characteristics and research capacity of each university.

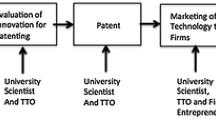

Source: Siegel and Phan (2004)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 2nd-term TLO project was completed in 2015. The policy program has continued in a similar fashion with emphasis on linkages between university TLOs and private/public research institutes and businesses since 2016.

The IACF is an organization established within the universities to promote industrial education and university–industry cooperation to strengthen the competitiveness of universities and contribute to the development of local communities and national competitiveness. Many IACFs in Korea have a legal basis on the Industrial Education Enhancement and Industry-Academia-Research Cooperation Promotion Act.

A sunset provision is a provision of a law that it will automatically be terminated after a fixed period unless it is extended by law (Collins Dictionary).

A discussion about the first-step estimation of Heckman’s two-step approach is provided in “Appendix”.

From 2011 to 2015, the IACFs spent an average of about 22.5 billion KRW in spending on industry-university cooperation activities.

References

Anderson, R., Daim, U., & Lavoie, F. (2007). Measuring the efficiency of university technology transfer. Technovation, 27, 306–318.

Arellano, M., & Bonhomme, S. (2016). Nonlinear panel data estimation via quantile regression. The Econometrics Journal, 19(3), C61–C94.

Caldera, A., & Debande, O. (2010). Performance of Spanish universities in technology transfer: An empirical analysis. Research Policy, 39(9), 1160–1173.

Carlsson, B., & Fridh, A.-C. (2002). Technology transfer in United States universities. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 12(1–2), 199–232.

Chapple, W., Lockett, A., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2005). Assessing the relative performance of U.K. University Technology Transfer Offices: Parametric and non-parametric evidence. Research Policy, 34(3), 369–384.

Cho, H. (2012). A study on the performance factors of technology commercialization of universities in Korea in terms of the resources-based view. The Journal of Intellectual Property, 7(3), 217–245 (in Korean).

Choi, T. (2011). Current status and development plan of University TLOs. Science & Technology Policy, 184, 38–50 (in Korean).

Choi, G. (2013). Research on the current conditions of university technology transfer commercialization and search for alternatives for improvement: A Case of University Technology Licensing Office (TLO). Master’s Thesis, Korea National University of Education (in Korean).

Friedman, J., & Silberman, J. (2003). University technology transfer: Do incentives, management, and location matter? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 28(1), 17–30.

Goldfarb, B., & Henrekson, M. (2003). Bottom-up versus top-down policies towards the commercialization of university intellectual property. Research Policy, 32(4), 639–658.

Graham, B. S., Hahn, J. Y., Poirier, A., & Powell, J. L. (2018). A quantile correlated random coefficients panel data model. Journal of Econometrics, 206(2), 305–335.

Han, D. (2010). An efficiency analysis study on the technology transfer of the university TLOs in Korea using SFA. In Conference proceedings (pp. 318–341). Korea Technology Innovation Society (in Korean).

Han, J. (2017). Assessing the commercialization policy of Korea’s national research and development projects: Focusing on the university technology transfer office. KDI Policy Study 2017-16, Korea Development Institute (in Korean).

Han, J. (2018). Effects of technology transfer policies on the technical efficiency of Korean University TTOs. KDI Journal of Economic Policy, 40(4), 23–45.

Han, S. H., & Kwon, K.-S. (2009). The relationship between institutional characteristics, funding structure, and knowledge-transfer performance of Korean Universities Engaged in Science and Engineering. The Korean Association for Public Administration, 43(4), 307–325 (in Korean).

Hyon, M., & Yoo, W. (2008). A study on the technology transfer efficiency for public institutes using DEA model. Journal of the Society of Korea Industrial and Systems Engineering, 31(2), 94–103 (in Korean).

Kim, B.-K., Cho, H.-J., & Og, J.-Y. (2011). A study on the technology commercialization process and performance of public research institutes in Korea using the structural equation model. Journal of Korea Technology Innovation Society, 14(3), 552–577 (in Korean).

Kim, J. (2006). A case study on regional technology transfer center and policy implications. Industrial Economic Analysis, 97, 25–35 (in Korean).

Kim, Y. (2013). The Ivory tower approach to entrepreneurial linkage: Productivity changes in university technology transfer. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(2), 180–197.

Kochenkova, A., Grimaldi, R., & Munari, F. (2016). Public policy measures in support of knowledge transfer activities: A review of academic literature. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41, 407–429.

Koenker, R., & Basset G. Jr. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 279–286.

Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology. (2016). 2016 Policy announcement (in Korean).

Korea Research Foundation. (2011). University TLO support project (CONNECT KOREA) casebook (in Korean).

Lee, S. S., Kim, Y. K., & Lee, S. (2012). Analysis of efficiency of universities and PRIs in technology transfer and its determinants. The Journal of Intellectual Property, 7(3), 163–185 (in Korean).

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. (2011). Expansion of support for strengthening capacity of the University TLOs. Press Release (May 6, 2011) (in Korean).

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology and Ministry of Knowledge Economy. (2011). Policy announcement for Leading TLO support project (in Korean).

Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning. (2013). Policy announcement for university TLO fostering project (in Korean).

Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. (2016). Research report on technology transfer and commercialization (in Korean).

Munari, F., Rasmussen, E., Toschi, L., & Villani, E. (2016). Determinants of the university technology transfer policy-mix: A cross-national analysis of gap-funding instruments. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41, 1377–1405.

O’Shea, R. P., Allen, T. J., Chevalier, A., & Roche, F. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation, technology transfer and spinoff performance of U.S. Universities. Research Policy, 34(7), 994–1009.

Ok, J.-Y., & Kim, B.-K. (2009). Measuring the performance of technology transfer activities of the public research institutes in Korea. Journal of Technology Innovation, 17(2), 131–158 (in Korean).

Parente, P. M. D. C., & Santos Silva, J. M. C. (2016). Quantile regression with clustered data. Journal of Econometric Methods, 5(1), 1–15.

Park, J.-B., & Ryu, H. (2010). Problems and improvement strategies of the promotion policy for technology licensing offices. e-KIET Industrial Economic Information, 486, 1–8 (in Korean).

Powers, J. B. (2003). Commercializing academic research: Resource effects on performance of university technology transfer. The Journal of Higher Education, 74(1), 26–50.

Siegel, D. S., & Phan, P. H. (2004). Analyzing the effectiveness of university technology transfer: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Rensselaer Working Papers in Economics, No. 0426.

Siegel, D. S., Veugelers, R., & Wright, M. (2007). Technology transfer offices and commercialization of university intellectual property: Performance and policy implications. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(4), 640–660.

Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D., & Link, A. (2003). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 32(1), 27–48.

Song, W. H. (2005). Development of technology transfer and commercialization implementation model for universities: CONNECT KOREA. Ministry of Education and Human Resources (in Korean).

Thursby, J., & Kemp, S. (2002). Growth and productive efficiency of university intellectual property licensing. Research Policy, 31(1), 109–124.

Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2002). Who is selling the Ivory tower? Source of growth in university licensing. Management Science, 48(1), 90–104.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2013). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (5th ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the very helpful suggestions by two referees that have greatly improved the paper. The usual caveat applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: The first step of Heckman’s two-step approach

Appendix: The first step of Heckman’s two-step approach

The first step of Heckman’s two-step approach is to predict the likelihood of selection for the financial support project by using a probit model (selection mechanism model). First of all, I estimated a selection mechanism model with a set of explanatory variables that correspond to the policy target selection criteria based on Table 11. Those variables are Total research fund, TLO employment, the number of domestic/overseas patent granted, operating expenses for industry-academia cooperation, total financial support, and the number of researchers. All the explanatory variables are lagged by a period. Table 12 displays the first-step probit model estimation results. By using the estimation results, I obtain the inverse Mill’s ratio, which means the likelihood of selection. The t-statistic on the inverse Mills ratio is 12.317 and statistically significant. This implies the selection model is appropriate.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, J. Identifying the effects of technology transfer policy using a quantile regression: the case of South Korea. J Technol Transf 45, 1690–1717 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09768-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09768-3