Abstract

The purpose of this article and the special issue is to improve our understanding of the theoretical, managerial, and policy implications of the effectiveness of technology transfer policies on entrepreneurial innovation. We accomplish this objective by examining the relationship between entrepreneurship, innovation and public policies in the 186 papers published from 1970 to 2019. Our analysis begins by clarifying the definition of entrepreneurial innovations and outlining the published research per context. We then present the seven papers that contribute to this special issue. We conclude by outlining an agenda for additional research on this topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since Schumpeter’s (1942) seminal work about “creative destruction”, entrepreneurship and innovation were strongly related topics. After 77 years, the innovation literature has paid attention to the structure and policies, while the entrepreneurship literature has been oriented to the individual or the firm (Zahra and Wright 2011). Even the disconnection of these fields, convergent studies have found that economies with robust technology transfer regulations provide a better supply of high-quality jobs and tend to be characterized by entrepreneurs with higher innovation contributions (Guerrero and Urbano 2017; Mosey et al. 2017; Urbano et al. 2018). It explains how the effect of regulations on the entrepreneurial innovation dynamic that can vary by regions, countries and continents. Previous studies also suggest that while there has been considerable empirical attention focused on studying the US technology transfer system and legislative systems, there is a dearth of empirical studies that examines the effectiveness of technology transfer policies and legislation that fostering entrepreneurial innovation in other continents (Audretsch 2004; Parsons and Rose 2004; Soete and Stephan 2004; Feldman et al. 2006; Nuur et al. 2009; Isenberg 2010; Audretsch and Link 2012; Grilli 2014; Flanagan and Uyarra 2016; Cuff and Weichenrieder 2017; Gorsuch and Link 2018; Link and van Hasselt 2019).

Inspired by these academic debates, this Special Issue addresses a better theoretical-empirical understanding and managerial implications behind the (un)success of technology transfer policies and legislation that stimulating entrepreneurial innovation across the world. More concretely, the objectives of this special issue were: (a) to motivate the academic debate about the effectiveness of technology transfer policies and legislation that promotes entrepreneurial innovations across contexts (social, university, organizational) and continents (Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe, North America, South America and Oceania); as well as, (b) to provide intercountry evidence and implications about the governments’ strategies implemented to promote the participation of the main actors involved in the entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystem to ensure the success of technology transfer policies and legislation (e.g., the extent and level of replication of US technology transfer policies and legislation in other regions/continents).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 clarifies the definitions of entrepreneurial innovations adopted in previous studies as well as their connection with a public policy perspective. Section 3 introduces a review of the existent literature adopting narrow criteria (entrepreneurship, innovation and policies) to evidence the contextual focus of previous studies. Section 4 focused on the contributions of each paper that comprises this SI, and lessons that we learned across several economies. In Sect. 5, we outline an agenda for additional research on this topic. In the final section, we conclude by outlining policy implications.

2 Entrepreneurial innovations and policy frameworks

2.1 Entrepreneurial innovations

There is not a consensus about what entrepreneurial innovations mean. Table 1 shows selected definitions of entrepreneurial innovations identified in the literature with also a policy focus.

Schumpeter (1942) was the first to introduce the concept of entrepreneurial innovation as the natural consequence of creative destruction produced by entrepreneurs when transformed the means in radical and marketable innovations. In this sense, the public policies approached issues as tax or labour or monetary that directly or indirectly could influence those transformations. Then, Von Bargen et al. (2003, p. 315) defined entrepreneurial innovations as a small group of high-growth companies that transformed the industries they entered, as well as highlighted the positive effect of policies on enhancing intellectual property protection through patent/copyright laws and judicial (p. 318). Afterwards, Cohen (2006, p. 1) introduced in his definition the notion of sustainability explaining that entrepreneurial innovations contribute towards a more sustainable society. Therefore, Cohen (2006, p. 4) also introduced the idea of an entrepreneurial ecosystem and the government responsibility that can foster/hinder entrepreneurial innovations through tax, incentives, subsidies and grants. Norbäck and Persson (2012, 488) made emphasis on the lower number of entrepreneurial innovations explaining that they made by outsiders of a specific industry. It is strongly related to the idea that few entrepreneurs develop entrepreneurial innovations with a high growth perspective. In this vein, the intensity of competition policies could incentive the development of entrepreneurial innovations (p. 490). Adopting an integral perspective, Autio et al. (2014, p. 1100) complemented previous definitions evidencing the intersection of entrepreneurship ecosystem and innovation ecosystem through multi-level processes, actors and context that regulates where entrepreneurs are developing disruptions of existing industries. In this sense, entrepreneurial innovation could be understood such as the development of entrepreneurial initiatives focused on radical innovations based on the co-creation among multiple actors (individuals and organizations) in a defined space/time such a result of a policy that foster entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystems (Autio et al. 2014). Complementary, Haufler et al. (2014, p. 14) explored the commercialization process of entrepreneurial innovations and how tax policies affect entrepreneurs’ choice of riskiness (or quality) of an innovation project, and on their mode of commercializing the innovation (market entry versus sale). Next, Guerrero and Urbano (2017, p. 295) expand the definition with the development of entrepreneurial innovations within university-industry collaborations in the context of emerging economies. Therefore, these authors evidenced the crucial role of subsidized public policy (p. 297). Moreover, Malerba and McKelvey (2018, p. 15) extend entrepreneurial innovation definitions with a learning perspective of organizations and how ecosystems influence on the generation and diffusion of marketable innovations.

2.2 Policy frameworks

Given the relevance of entrepreneurial innovations, governments across the globe have implemented several policy frameworks and instruments that directly or indirectly have contributed to fostering entrepreneurial innovations. Analysing of the OECD platform, Table 2 summarizes the instruments and frameworks adopted by the OECD countries to foster entrepreneurial innovations.

The positive signal of this analysis was the recognition of different instruments from a supply side (direct funding for R&D firms, fiscal measures, debt schemes, technology services), a demand side (innovation procurement schemes), and connectivity (clusters) associated with elements that facilitated the development of entrepreneurial innovations. Moreover, the implementation of regulatory frameworks focused on intellectual property rights, product market regulation, administrative procurements, as well as complementary frameworks on financing, market, labour, and transference of knowledge, reveal the government interest on technology, innovation, knowledge transfer-commercialization, and entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, the negative signal was the limited, mixed and inconclusive evidence regarding the effectiveness of these listed policy frameworks and instruments (WIPO 2004; OECD 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, c, d). As a consequence, nowadays it is not possible to understand if the expected objectives have been achieved, if the impacts generated per each dollar beyond them have covered the expectative, or if the metrics are measuring the outcomes correctly (Winters and Stam 2007; Wölfl et al. 2010; Shapira et al. 2011; Toner 2011; Steen 2012; Westmore 2013; Cunningham et al. 2016). These two signals are part of the research motivation of this Special Issue.

3 Analysing the link between entrepreneurship, innovation and policy frameworks on published research

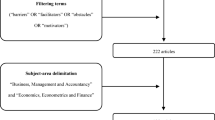

After observing the lower number of publications about “entrepreneurial innovation”, we decided to adopt a broad analysis of research published in the Web of Science database to provide a better understanding into the links between entrepreneurial innovations and public policies. Concretely, we extend the research adopting the following the criteria: (1) using three selecting keywords related to entrepreneurship, innovation and policies in title and/or abstract included per paper; and (2) publication between 1971 (to see the influence of the Schumpeter seminal work published in 1942) and 2019 (February), inclusive. We only identify 347 articles mostly concentrated in the last decade.

After the cleaning process, we selected 186 that were coded into one of ten categories—organizational context (strategies), market conditions (industry effects), social context (societal effects), institutional context (informal institutional conditions), public policy (formal institutional conditions), digital context (digitalization effects), university context (university effects), ecosystem (system effect), economic growth (geographical effects), and literature review papers. The rationale for these categories was the framework proposed by Autio et al. (2014, p. 1098). We adopted their “entrepreneurial innovation and context framework” classification for two reasons. First, it allows identifying each contextual dimension where public regulations and policies could produce influences that provide some insights about their effectiveness. Second, it allows mapping the geographic research settings where those public regulations and policies were implemented.

Adapting Autio et al. (2014, p. 1098) framework, Fig. 1 shows our categories’ distribution of published papers about entrepreneurship, innovation and policy from 1971 to 2019 (“Appendix 1”).

Source: Adapted from Autio et al. (2014, p. 1098)

Research published during 1941–2019 (Feb) linking entrepreneurship, innovation and policy.

The majority of publications are concentrated on organizational and university contexts. For one hand, the 24% of published studies were primarily contextualized into organizations that design strategies, configure networks, and modify governance structures looking for capturing positive outcomes (performance, productivity and sustainability) through innovation and entrepreneurship orientations that are influenced by R&D investments, IPR laws and corporate venturing public policies (e.g., see Burgelman 1986; Studdard and Darby 2008; Dunlap-Hinkler et al. 2010; Ryan and Giblin 2012; Nathan and Lee 2013; Mrożewski and Kratzer 2017; Urbaniec 2018). For the other hand, 21% of published studies were contextualized into universities with capabilities that transform knowledge into disruptive/commercial innovations or technologies but that is also conditioned by IPR laws such as copyright, patents, licenses, trademarks, trade secrets, and among others (e.g., see Goldsmith and Kerr 1991; Zenie 2003; Sáez-Martínez et al. 2014; Thongpravati et al. 2016; Guerrero et al. 2016; Marozau and Guerrero 2016; Guerrero and Urbano 2017; Guerrero et al. 2019; Eesley and Miller 2018; Qian et al. 2018).

The institutional context also has good representativeness in our review. The 15% of published studies focused on evaluating the efficiency of specific policy frameworks, country regulations and governmental instruments (formal institutional context) that enhance or diminish the development/commercialization of entrepreneurial innovations (e.g., see Lo et al. 2005; Tomes et al. 2000; Woolley and Rottner 2008; Audretsch and Link 2012; Batabyal and Nijkamp 2012; Alcalde and Guerrero 2016; Langhorn 2014; Audretsch et al. 2016; Nnakwe et al. 2018). Moreover, matching informal institutional context, a set of published studies (6%) has explored how certain institutional voids, ethical issues and culture affects the development of entrepreneurship and innovations (e.g., see Golodner 2001; Brenkert 2009; Letaifa and Rabeau 2013). The rest of the published studies explored entrepreneurial innovations associated with societal contexts, market context, digital contexts, and the link with economic development.

4 Special issue’s contributions across continents

Achieving the SI objectives, our initial call for paper received more than 25 manuscripts that were pre-selected adopting the previous criterions (fit with the SI). After this pre-selection process, ten manuscripts were invited to participate in the review process. Finally, seven manuscripts were accepted for being part of this special issue. Table 3 summaries the manuscripts’ contributions to this special issue.

4.1 Africa [Egypt]

Positioning in the African context, Hadidi and Kirby contributed with a review of the literature on the effectiveness of instruments that promote technology transfer and foster entrepreneurial innovation in the Egyptian university context. Designing a four-step methodology, authors collected and triangulated numerous sources of information (in-depth interviews with experts, a questionnaire survey of 400 Egyptian Science, Engineering and Technology academics, three case studies of Technology Transfer Offices, and a 237 respondent industry survey). Their findings provided us evidence about the limited effectiveness of current Egyptian policies oriented to fostering entrepreneurial innovations in this lower income economy.

4.2 America [cross Latin-American and Caribbean countries and North-America]

Setting the research across 14 Latin-American and the Caribbean countries, Amorós, Poblete and Mandakovic explored the extent of effectiveness of government intervention, R + D, and pro-innovation mechanisms in the likelihood of being an innovative entrepreneur with high ambitions of growing (their proxy of entrepreneurial innovations). Adopting a longitudinal approach (2006–2015), authors found no conclusive results about the effectiveness of their narrow measures of technology transfer policies but intuitively consider that combining these narrow policies with an innovation-driven environment the creation of ambitious entrepreneurs could increase in the analyzed middle-high income economies.

Reviewing the legislative emphasis on technology transfers from U.S. federal laboratories, Link and Scott proposed a framework to describe how private sector firms benefit from the adoption of technologies from federal laboratories. Authors explained how a social gain will be realized when private firms increase profits for the using the technology, as well as when consumers have higher reservation prices for higher quality products/services and pay lower prices because firms’ costs are lower. Authors concluded that research is needed on the history and application of public sector initiatives related to the transfer of technology from publicly funded laboratories and/or institutions in other countries, as well as on evaluations of the social benefits attributable to the transferred technologies.

4.3 Europe [cross European countries, Germany and Croatia]

Taking a longitudinal angle across 32 European countries, van Stel, Lyalkov, Millán and Millán explored the relationship between country-level expenditures on R&D, Intellectual Property Rights (IPR), and individual-level entrepreneurial performance measured by earnings (their proxy of entrepreneurial innovation). Authors found a positive effect of both R&D expenditures and IPR on the quality/quantity of entrepreneurs’ earnings, as well as an intriguing moderation effect of IPR that reduces the positive relationship between R&D and entrepreneurs’ earnings. As a consequence, authors contribute with interesting implications for policymakers.

Exploring this phenomenon in the German context, Cunningham, Lehmann, Menter and Seitz exanimated the simultaneous effects on entrepreneurial and innovative outcomes of university focused technology transfer policies (their measure of entrepreneurial innovations). Concretely, these authors analyzed the effect of the far-reaching legislation change in Germany, reforming the old ‘professor’s privilege’ (Hochschullehrerprivileg) associated with intellectual property rights of inventions made by scientists. Adopting a longitudinal analysis, authors found an initial positive effect on universities as measured by start-ups and patents but with changed effect over time, leading to some unintended consequences. As a consequence, authors contribute with interesting implications for policymakers regarding the introduction of reforms in technology transfer policies.

Setting the research during a transitionary period of Croatia, Svarc and Dabic focused on understanding if technology transfer policies adopted in the socialist era were improved after entry into a capitalist era (being part of the European Union). Authors found that, despite the legislative assistance of the European Union, technology transfer is unfolding very slowly. The evolutionary phases adopted three models: (a) science-based models in socialism, (b) endeavours towards innovation models in transition, and (c) bureaucratic models driven by the EU cohesion policy. Therefore, the authors concluded that bureaucratic-driven types of technology transfer should be coupled with nationally concerned actions on overall economic and political reforms to gain effective results from their technology transfer efforts.

4.4 Oceania [Australia and New Zealand]

Developing a cross-continent comparison between Oceania and Europe, Ferreira, Fernandes and Ratten focused on environments that promote patents on growth economic. More concretely, this manuscript contributed to the literature on cross-continent the effects of technology transfer policies by examining how the outcomes of these policies—patents—(their measure of entrepreneurial innovations) influence economic growth rate. Based on their comparison analysis, authors captured some insights about the effect of government policies that enhancing technology transfer and economic growth. As a consequence, the authors contribute with a benchmark and several suggestions for improving the effects of governmental support on entrepreneurial innovations.

5 Discussing a research agenda

5.1 Geographic view

Embracing a geographic view, Fig. 2 shows that the 186 published papers (in grey color) mostly setting this phenomenon in the context in high-income economies (48%). It is also important to mention that the analysis of this phenomenon in low-income economies (20%), middle-income economies (13%), and mixed-income economies (11%) increased in the last decade but not their representativeness. However, being marked in grey color does mean the existence of multiple studies per country (e.g., maybe just one). Moreover, our special issue also contributes with relevant insights in several countries across the globe (in black color). In this assumption, future research is an open window for answering the next questions: Which technology transfer policies, legislation and strategies have been implemented by governments across countries/continents to stimulate entrepreneurial innovations? What institutional supports and arrangements have been put in place by regional/national governments to support effective policy implementation? What extent has the Bayh–Dole Act, SBIR and other programmes that been replicated into other national technology transfer and innovation systems (e.g., lower and middle income economies tend to replicate them)? How is the level of efficiency or inefficiency behind these replications?

Another interesting academic debate to be considered in future research is the exploration of digital contexts. As we evidenced in section three, it is a new research line that is growing in recent years. In this sense, the digitalization does not consider geographic limits but should take into account the most effective mechanisms that support entrepreneurial innovations. In this assumption, we encourage future researchers to explore questions like which strategies have been implemented into the digital platforms to stimulate entrepreneurial innovations? What is the effectiveness of these strategies? Is digital context an opportunity for governments involved in lower-middle income interested in fostering entrepreneurial innovations?

5.2 Methodological view

Both the revised literature and the manuscript in this special issue adopted different methodologies. More advanced economies showed robust and complex econometric analysis. This pattern is explained by the existence of longitudinal datasets that capture the variables required into the evaluation of the effectiveness of technology policies or programs. In developing economies, researchers adopted qualitative methodologies for exploring in-depth the phenomenon but also limited by the lack of public information. Instead of considering this limitation as a problem, future research has the opportunity to propose novel methodological approaches that allows understanding of the effectiveness of technology transfer policies on entrepreneurial innovations in lower and middle income economies. In this regard, potential research questions could be what measures have been implemented by national technology transfer systems to evaluate the performance and the success of their policies? How do these measures have influenced organizational and individual actors involved in entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystems? What types of measures are the most appropriated to capture the impact of technology transfer policies and legislation in shaping innovation patterns and industry structures?

5.3 Theoretical view

We observe that to capture some insights about the effectiveness of technology transfer policies on entrepreneurial innovations is necessary to consider the mature, the dynamics and the evolutionary process. Theoretically, future research has the opportunity to adopt multidisciplinary approaches for understanding evolutionary and dynamic processes faced by individuals, organizations and countries. In this regard, potential research questions could be which theoretical approaches could help us to understand the antecedents of entrepreneurial innovations and outcomes associated with the effectiveness of national and transnational technology transfer policies? Which theoretical approaches are the most appropriated to identify contextual conditions that could stimulate entrepreneurial innovations’ dynamic and evolutionary processes?

5.4 Policymakers view

From a policymakers view, transparency and objective metrics associated with each policy frameworks and instruments are a crucial element for evaluating their effectiveness and legitimizing the role of policymakers. It implies a previous design of metrics that by transparency laws the providers of public resources, as well as the benefits of those public resources, should generate as part of the procurement to enhance entrepreneurial innovations. In this regard, potential research questions could be how different countries could implement best practices about transparency and the generation of objective metrics about entrepreneurial innovations? Are mandatory indicators a solution for understanding and evaluating the real effects and impacts of existent policies that fostering entrepreneurial innovations? Is the stakeholder theory an appropriate theory for analysing this phenomenon?

6 Concluding remarks

This special issue represents an effort to draw together research that examines the effectiveness of technology transfer policies and legislation that fosters entrepreneurial innovation across continents (Africa, Europe, North America, South America and Oceania). Previously, a significant body of empirical research has been contributed the effectiveness of US technology transfer policies and legislation such as the Bayh–Dole Act and the Small Business Innovation Research Programme (see Audretsch et al. 2002; Mowery et al. 1999; Shane 2004; Siegel et al. 2003). Based on our mapping, the academic debate about the effectiveness of policies still demands evidence at country, cross-country, and cross-continent with rigorous methodologies and robust datasets. Consistent with this, we dissecting the literature of entrepreneurship and innovation for evidencing the numerous disruptive innovations introduced by entrepreneurial firms (e.g., electronic, energy, biotechnology, technological sectors) as well as how entrepreneurial innovation could be considered an outcome of effective technology transfer regulations across by regions, countries and continents (Autio et al. 2014).

For instance, studies provide policymakers with evidence that can inform and shape future legislative and technology transfer policies. However, there is a dearth of similar type studies in other geographic regions that examines the effectiveness of technology transfer policies. National governments in other regions have used a mix of policy approaches to encourage higher levels of technology transfer between different actors in national economies. Some of these technology transfer policy initiatives are cross-country such as Europe’s Horizon 2020 and previous framework programmes. At the same time, some of these policy initiatives are implemented without any legislative support, as is the case with significant technology transfer policy initiatives in the USA. The special issue encourages to the academic community to explore the effectiveness of technology transfer policies and legislation in a non-US context in an effort to develop new empirical insights into the effectiveness of technology transfer policies across continents.

References

Alcalde, H., & Guerrero, M. (2016). Open business models in entrepreneurial stages: Evidence from young Spanish firms during expansionary and recessionary periods. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 393–413.

Audretsch, D. B. (2004). Sustaining innovation and growth: Public policy support for entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation, 11(3), 167–191.

Audretsch, D. B., Kuratko, D. F., & Link, A. N. (2016). Dynamic entrepreneurship and technology-based innovation. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 26(3), 603–620.

Audretsch, D. B., & Link, A. N. (2012). Entrepreneurship and innovation: Public policy frameworks. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 1–17.

Audretsch, D. B., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2002). Public/private technology partnerships: Evaluating SBIR-supported research. Research Policy, 31(1), 145–158.

Autio, E., Kenney, M., Mustar, P., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2014). Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Research Policy, 43(7), 1097–1108.

Batabyal, A. A., & Nijkamp, P. (2012). A Schumpeterian model of entrepreneurship, innovation, and regional economic growth. International Regional Science Review, 35(3), 339–361.

Brenkert, G. G. (2009). Innovation, rule breaking and the ethics of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 448–464.

Burgelman, R. A. (1986). Managing corporate entrepreneurship: New structures for implementing technological innovation. In M. Horwith (Ed.), Technology in the modern corporation (pp. 1–13). New York: Pergamon.

Cohen, B. (2006). Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(1), 1–14.

Cuff, K., & Weichenrieder, A. (2017). Introduction to the special issue on entrepreneurship, innovation and public policy. International Tax and Public Finance, 24(4), 547.

Cunningham, P., Gök, A., & Larédo, P. (2016). The impact of direct support to R&D and innovation in firms. In J. Edler, et al. (Eds.), Handbook of innovation policy impact (p. 54). Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.

Dunlap-Hinkler, D., Kotabe, M., & Mudambi, R. (2010). A story of breakthrough versus incremental innovation: Corporate entrepreneurship in the global pharmaceutical industry. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(2), 106–127.

Eesley, C. E., & Miller, W. F. (2018). Impact: Stanford University’s economic impact via innovation and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 130–278.

Feldman, M., Gertler, M., & Wolfe, D. (2006). University technology transfer and national systems of innovation: Introduction to the special issue of industry and innovation. Industry and Innovation, 13(4), 359–370.

Flanagan, K., & Uyarra, E. (2016). Four dangers in innovation policy studies: And how to avoid them. Industry and Innovation, 23(2), 177–188.

Goldsmith, R. E., & Kerr, J. R. (1991). Entrepreneurship and adaption-innovation theory. Technovation, 11(6), 373–382.

Golodner, A. M. (2001). Antitrust, innovation, entrepreneurship and small business. Small Business Economics, 16(1), 31–35.

Gorsuch, J., & Link, A. N. (2018). Nanotechnology: A call for policy research. Annals of Science and Technology Policy, 2(4), 307–463.

Grilli, L. (2014). High-tech entrepreneurship in Europe: A heuristic firm growth model and three “(un-) easy pieces” for policy-making. Industry and Innovation, 21(4), 267–284.

Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2017). The impact of Triple Helix agents on entrepreneurial innovations’ performance: An inside look at enterprises located in an emerging economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 119, 294–309.

Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., Fayolle, A., Klofsten, M., & Mian, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial universities: Emerging models in the new social and economic landscape. Small Business Economics, 47(3), 551–563.

Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., & Herrera, F. (2019). Innovation practices in emerging economies: Do university partnerships matter? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 615–646.

Haufler, A., Norbäck, P. J., & Persson, L. (2014). Entrepreneurial innovations and taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 113, 13–31.

Isenberg, D. J. (2010). THE BIG IDEA how to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50.

Langhorn, K. (2014). Encouraging entrepreneurship with innovation vouchers: Recent experience, lessons, and research directions. Canadian Public Administration, 57(2), 318–326.

Letaifa, S. B., & Rabeau, Y. (2013). Too close to collaborate? How geographic proximity could impede entrepreneurship and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2071–2078.

Link, A. N., & van Hasselt, M. (2019). Exploring the impact of R&D on patenting activity in small women-owned and minority-owned entrepreneurial firms. Small Business Economics, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-00130-9

Lo, T. H., Liou, S., & Yuan, B. (2005). Organisation innovation and entrepreneurship: The role of the national laboratories in promoting industrial development. International Journal of Technology Management, 30(1–2), 67–84.

Malerba, F., & McKelvey, M. (2018). Knowledge-intensive innovative entrepreneurship integrating Schumpeter, evolutionary economics, and innovation systems. Small Business Economics, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0060-2

Marozau, R., & Guerrero, M. (2016). Conditioning factors of knowledge transfer and commercialisation in the context of post-socialist economies: The case of Belarusian higher education institutions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 27(4), 441–462.

Mosey, S., Guerrero, M., & Greenman, A. (2017). Technology entrepreneurship research opportunities: Insights from across Europe. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(1), 1–9.

Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R., Sampat, B., & Ziedonis, A. A. (1999). The effects of the Bayh–Dole Act on US university research and technology transfer: An analysis of data from Columbia University, the University of California, and Stanford University. Research Policy, 29, 729–740.

Mrożewski, M., & Kratzer, J. (2017). Entrepreneurship and country-level innovation: Investigating the role of entrepreneurial opportunities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(5), 1125–1142.

Nathan, M., & Lee, N. (2013). Cultural diversity, innovation, and entrepreneurship: Firm-level evidence from London. Economic Geography, 89(4), 367–394.

Nnakwe, C. C., Cooch, N., & Huang-Saad, A. (2018). Investing in academic technology innovation and entrepreneurship: Moving beyond research funding through the NSF I-CORPS™ program. Technology & Innovation, 19(4), 773–786.

Norbäck, P. J., & Persson, L. (2012). Entrepreneurial innovations, competition and competition policy. European Economic Review, 56(3), 488–506.

Nuur, C., Gustavsson, L., & Laestadius, S. (2009). Promoting regional innovation systems in a global context. Industry and Innovation, 16(1), 123–139.

OECD. (2008). Promoting entrepreneurship and innovative SMEs in a global economy. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264044357-en.

OECD. (2009). Cluster, innovation and entrepreneurship. Paris: OECD.

OECD (2010). Knowledge networks and markets: A typology of markets in explicit knowledge. DSTI/IND/STP/ICCP(2010)3.

OECD. (2011a). Business innovation policies: Selected country comparisons. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264115668-en.

OECD. (2011b). Intellectual assets and innovation: The SME dimension, OECD studies on SMEs and entrepreneurship. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012a). Financing business R&D and innovation, in OECD science, technology and industry outlook 2012. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/sti_outlook-2012-12-en.

OECD. (2012b). Stimulating demand for innovation, in OECD science, technology and industry outlook 2012. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/sti_outlook-2012-en.

OECD. (2012c). Science, technology and industry outlook 2012. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2012d). Operational environment for SMEs (dimension 4): Make public administrations responsive to SMEs’ needs (small business act principle 4), in SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2012: Progress in the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264178847-11-en.

Parsons, M. C., & Rose, M. B. (2004). Communities of knowledge: Entrepreneurship, innovation and networks in the British outdoor trade, 1960–90. Business History, 46(4), 609–639.

Qian, X. D., Xia, J., Liu, W., & Tsai, S. B. (2018). An empirical study on sustainable innovation academic entrepreneurship process model. Sustainability, 10(6), 1974.

R&D Tax Incentives: www.oecd.org/sti/rd-tax-stats.htm.

Ryan, P., & Giblin, M. (2012). High-tech clusters, innovation capabilities and technological entrepreneurship: Evidence from Ireland. The World Economy, 35(10), 1322–1339.

Sáez-Martínez, F. J., González-Moreno, Á., & Hogan, T. (2014). The role of the University in eco-entrepreneurship: Evidence from the Eurobarometer Survey on Attitudes of European Entrepreneurs towards Eco-innovation. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, 13(10), 2541.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

Shane, S. (2004). Encouraging university entrepreneurship? The effect of the Bayh–Dole Act on university patenting in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 127–151.

Shapira, P., Youtie, J., & Kay, L. (2011). Building capabilities for innovation in SMEs: A cross-country comparison of technology extension policies and programmes. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 3, 254–272.

Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D., & Link, A. (2003). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 32(1), 27–48.

Soete, B., & Stephan, A. (2004). Introduction: Entrepreneurship, innovation and growth. Industry and Innovation, 11(3), 161–165.

Steen, J. V. (2012). Modes of public funding of research and development: Towards internationally comparable indicators. In OECD science, technology and industry working papers, 2012/04. OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k98ssns1gzs-en.

Studdard, N., & Darby, R. (2008). From social capital to human resource development: A cross cultural study of the role of HRM in innovation and entrepreneurship in high technology organisations. European Journal of International Management, 2(3), 333–355.

Thongpravati, O. N. N. I. D. A., Maritz, A., & Stoddart, P. A. U. L. (2016). Fostering entrepreneurship and innovation through a biomedical technology PhD program in Australia. International Journal of Engineering Education, 32(3), 1222–1235.

Tomes, A., Erol, R., & Armstrong, P. (2000). Technological entrepreneurship: Integrating technological and product innovation. Technovation, 20(3), 115–127.

Toner, P. (2011). Workforce skills and innovation: An overview of major themes in the literature. In OECD education working papers, no. 55. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kgk6hpnhxzq-en.

Urbaniec, M. (2018). Sustainable entrepreneurship: Innovation-related activities in European enterprises. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 27(4), 1773–1779.

Urbano, D., Guerrero, M., Ferreira, J. J., & Fernandes, C. I. (2018). New technology entrepreneurship initiatives: Which strategic orientations and environmental conditions matter in the new socio-economic landscape? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9675-3

Von Bargen, P., Freedman, D., & Pages, E. R. (2003). The rise of the entrepreneurial society. Economic Development Quarterly, 17(4), 315–324.

Westmore, B. (2013). R&D, patenting and growth: The role of public policy. In OECD economics department working papers, no. 1047. OECD Publishing.

Winters, R., & Stam, E. (2007). Innovation networks of high-tech SMEs: Creation of knowledge but no creation of value (pp. 2007–2042). No: Jena Economic Research Papers.

WIPO. (2004). Intellectual property rights and innovation in small and medium enterprises. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organisation.

Wölfl, A. et al. (2010). Product market regulation: Extending the analysis beyond OECD countries. In OECD economics department working papers, no. 799. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5km68g3d1xzn-en.

Woolley, J. L., & Rottner, R. M. (2008). Innovation policy and nanotechnology entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), 791–811.

Zahra, S., & Wright, M. (2011). Entrepreneurship’s next act. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25, 67–83.

Zenie, F. H. (2003). Innovation and entrepreneurship: From science to practice. American Laboratory, 35(20), 42–45.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Al Link, the JoTT editor, for his invaluable support. Guest editors also manifest their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers who participated during the review process for their insightful comments that contributed substantially to the development of the SI’s manuscripts. Finally, David Urbano acknowledges the financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [Project ECO2017-87885-P], the Economy and Knowledge Department—Catalan Government [Project 2017-SGR-1056] and ICREA under the ICREA Academia Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

See Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Guerrero, M., Urbano, D. Effectiveness of technology transfer policies and legislation in fostering entrepreneurial innovations across continents: an overview. J Technol Transf 44, 1347–1366 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09736-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09736-x

Keywords

- Entrepreneurship

- Innovation

- Entrepreneurial innovations

- Technology transfer policies

- Evaluation of public policy effectiveness

- Entrepreneurship ecosystems

- Innovation ecosystems

- Economywide country studies