Abstract

Foreign-born workers have made significant and substantial contributions to economic productivity and new firm creation in the United States. This paper identifies predictors of entrepreneurial participation among foreign-born workers, combining nationally representative survey datasets covering the U.S. resident, college-educated workforce with country-of-origin macro statistics from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Immigrants who come to the U.S. after earning university degrees abroad are more likely to own businesses than other college-educated, U.S. resident workers. However, much of their higher rate of business ownership can be attributed to differences in demographic characteristics, such as years of postgraduate work experience and marital status. By contrast, science and engineering-based business ownership is most common among immigrants who came to the U.S. to pursue higher education. Furthermore, after controlling for differences in human capital, U.S.-trained adult immigrants have higher propensity to own businesses than other foreign-born workers and native U.S. citizens, overall. U.S.-trained immigrants’ higher probability of business ownership is not explained by differences in human capital or other demographic characteristics, but does seem partly attributable to differences across foreign-born workers’ countries-of-origin. Specifically, adult immigrants and foreign temporary residents from countries that offer entrepreneurs lower levels of cultural support are more likely to start and own U.S. businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Mueller and Thomas (2000) for more extensive review of this literature.

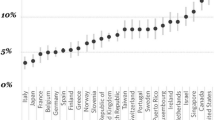

The GSS survey instrument begins the section on values and attitudes with, “Now I will briefly describe some people. Please listen to each description and tell me how much each person is or is not like you.” The respondent is handed a card with a six-point scale, including the following options: Very much like me; Like me; Somewhat like me; A little like me; Not like me; Not like me at all. Valuing autonomy, freedom, and independence corresponds to the statement, “It is important to [him/her] to make [his/her] own decisions about what s/he does. S/he likes to be free and not depend on others.” The percentages in Fig. 1 correspond to the share of respondents in each group who said this statement is “Like me” or “Very much like me”. Valuing success and wanting recognition for achievement corresponds to the same responses for the statement, “Being very successful is important to [him/her]. S/he hopes people will recognize [his/her] achievements.” Finally, the construct Risk-Tolerant is measured by individuals’ responses to the statement: “S/he looks for adventures and likes to take risks. S/he wants to have an exciting life.” Risk-tolerant is coded to 1 if the respondent answers with any of the first four responses, from “very much like me” to “a little like me”. If the respondent answers “not like me” or “not like me at all”, we view them as risk-averse, and code this variable as zero.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Understanding F-1 OPT Requirements,” at http://www.uscis.gov/eir/visa-guide/f-1-opt-optional-practical-training/understanding-f-1-opt-requirements, last accessed 6 February 2015. See also U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Working in the United States,” at http://studyinthestates.dhs.gov/working-in-the-united-states, and “International Students and Entrepreneurship,” at http://studyinthestates.dhs.gov/international-students-and-entrepreneurship, both last accessed 24 July 2015.

Among other (non-STEM) college-educated foreign temporary resident business owners, about 1 in 5 indicated “other” visa type, meaning their visa was not “for temporary work” (H-1B, L-1, etc.), nor “for study or training” (F-1, J-1, H-3), nor as a dependent on someone else’s visa. Cognitive interviews with college-educated foreign temporary resident workers may help to clarify how respondents categorize E-2 Treaty Investor visas (as “for temporary work” versus “other”), and time spent working with an OPT extension to the F-1 visas (“for study or training,” versus “for temporary work” or “other”).

See U.S. Department of State website for list of E-2 Treaty Countries with which the United States maintains applicable treaties of commerce and navigation (last accessed 11 February 2015): http://travel.state.gov/content/visas/english/fees/treaty.html.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “National Interest Waiver,” (last accessed 24 July 2015) at

http://www.uscis.gov/eir/visa-guide/eb-2-employment-based-second-preference/national-interest-waiver.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Understanding the EB-2 Requirements for Exceptional Ability,” last accessed 24 July 2015 at http://www.uscis.gov/eir/visa-guide/eb-2-employment-based-second-preference/understanding-eb-2-requirements-exceptional-ability.

I gratefully acknowledge Katherine Schmeiser for providing these data.

It is important to note, however, that the initial question does not specify the visa type at most recent entry. This distinction has practical implications for the responses’ use, as for example, individuals who first entered the U.S. as children of temporary workers but then returned to their home country, completed college and even graduate school abroad, may then return as adults on their own temporary worker visas, and ultimately acquire permanent residence or become naturalized citizens. Qualitatively and practically speaking, the unobserved abilities and preferences of an individual who immigrates to the U.S. as an adult worker but had some childhood experience of living in the U.S. may be significantly different from those of an individual who first entered the U.S. as a trailing spouse on their partner’s H-1B visa.

We define this group as the subset of non-incorporated self-employed individuals who report they have fewer than ten employees (zero included), but do not directly supervise any workers and have not “recommended or initiated personnel actions such as hiring, firing, evaluating or promoting others”.

References

Ács, Z. J., Szerb, L., & Autio, E. (2013). Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2013. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Anderson, S. (2013). American made 2.0: How immigrant entrepreneurs continue to contribute to the U.S. economy. Arlington, VA: National Foundation for American Policy.

Åstebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and misfits: self-employment and labor market frictions. Management Science, 57(11), 1999–2017. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1110.1400.

Baum, J. R., Olian, J. D., Erez, M., Schnell, E. R., Smith, K. G., Sims, H. P., et al. (1993). Nationality and work role interactions: A cultural contrast of Israeli and U.S. entrepreneurs’ versus managers’ needs. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(6), 499–512.

Belot, M. V. K., & Hatton, T. J. (2012). Immigrant selection in the OECD. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 114(4), 1105–1128.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrepreneurs: Organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19(1), 69–89.

BLS. (2012). Attachment C: Detailed 2010 SOC occupations included in STEM SOC policy committee recommendation to OMB 2010 SOC User Guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Blume-Kohout, M. E. (2014). Understanding the gender gap in STEM fields entrepreneurship. SBA Office of Advocacy Report no. 424. Washington, DC: U.S. Small Business Administration.

Blume-Kohout, M. E. (2015). Imported entrepreneurs: Foreign-born scientists and engineers in U.S. STEM fields entrepreneurship. SBA Office of Advocacy Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Small Business Administration (in press).

Borjas, G. J. (1986). The self-employment experience of immigrants. Journal of Human Resources, 21(4), 485–506.

Borjas, G. J. (1987). Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review, 77(4), 531–553.

Borjas, G. J. (2002). An evaluation of the foreign student program. Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies. Available at: http://cis.org/ForeignStudentProgram.

Brücker, H., & Defoort, C. (2009). Inequality and the self-selection of international migrants: Theory and new evidence. International Journal of Manpower, 30(7), 742–764.

Chellaraj, G., Maskus, K. E., & Mattoo, A. (2008). The contribution of international graduate students to U.S. innovation. Review of International Economics, 16(3), 444–462.

Clark, X., Hatton, T. J., & Williamson, J. G. (2007). Explaining U.S. immigration, 1971-1998. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 359–373.

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001–1022.

Elfenbein, D. W., Hamilton, B. H., & Zenger, T. R. (2010). The small firm effect and the entrepreneurial spawning of scientists and engineers. Management Science, 56(4), 659–681. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1090.1130.

Etzioni, A. (1987). Entrepreneurship, adaptation and legitimation: A macro-behavioral perspective. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 8(2), 175–189.

Fairlee, R. W. (2008). Estimating the contribution of immigrant business owners to the U.S. economy. SBA office of advocacy report no. 334. Washington, DC: U.S. Small Business Administration.

Fairlee, R. W. (2014). Kauffman index of entrepreneurial activity: 1996–2013. Kansas City, MO: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Fairlee, R. W., & Robb, A. (2007). Families, human capital, and small business: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 60(2), 225–245.

Hart, D. M., & Ács, Z. J. (2011). High-tech immigrant entrepreneurship in the United States. Economic Development Quarterly, 25(2), 116–129.

Hegde, D., & Tumlinson, J. (2015). Unobserved ability and entrepreneurship. Available from SSRN. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2596846

Hout, M., & Rosen, H. S. (2000). Self-employment, family background, and race. Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 670–692.

Hundley, G. (2000). Male/female earnings differences in self-employment: The effects of marriage, children, and the household division of labor. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54(1), 95–114.

Hunt, J. (2011). Which immigrants are most innovative and entrepreneurial? Distinctions by entry visa. Journal of Labor Economics, 29(3), 417–457.

Hunt, J., & Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010). How much does immigration boost innovation? American Economic Journal-Macroeconomics, 2(2), 31–56.

Kerr, S. P., & Kerr, W. R. (2015). Immigrant Entrepreneurs. In J. Haltiwanger, E. Hurst, J. Miranda, & A. Schoar (Eds.), Measuring entrepreneurial businesses: Current knowledge and challenges. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kim, P. H., Aldrich, H. E., & Keister, L. A. (2006). Access (not) denied: The impact of financial, human, and cultural capital on entrepreneurial entry in the United States. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 5–22.

Lévesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2006). The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 177–194.

Light, A., & Munk, R. (2015). Business ownership vs. self-employment. Paper presented at the Society of Labor Economists Annual Meeting, Montreal, Canada, June 2015.

Lofstrom, M., Bates, T., & Parker, S. C. (2014). Why are some people more likely to become small-businesses owners than others: Entrepreneurship entry and industry-specific barriers. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 232–251.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Mueller, S. L., & Thomas, A. S. (2000). Culture and entrepreneurial potential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51–75.

No, Y., & Walsh, J. P. (2010). The importance of foreign-born talent for U.S. innovation. Nature Biotechnology, 28, 289–291.

Roach, M., & Sauermann, H. (2015). Founder or joiner? The role of preferences and context in shaping different entrepreneurial interests. Management Science, 61(9), 2160–2184.

Shane, S. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Stuart, T. E., & Ding, W. W. (2006). The social structural antecedents of commercial activity in the life sciences. American Journal of Sociology, 112(1), 97–144.

Suter, B., & Jandl, M. (2008). Train and retain: National and regional policies to promote the settlement of foreign graduates in knowledge economies. International Migration & Integration, 9, 401–418.

UCSIS. (2010). Questions & answers: USCIS issues guidance memorandum on establishing the “Employee-Employer Relationship” in H-1B petitions. http://www.uscis.gov/news/public-releases-topic/business-immigration/questions-answers-uscis-issues-guidance-memorandum-establishing-employee-employer-relationship-h-1b-petitions. Accessed February 6, 2015.

Unger, J. M., Rauch, A., Frese, M., & Rosenbusch, N. (2011). Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 341–358.

USCIS. (2010). Determining employer-employee relationship for adjudication of H-1B petitions, including third-party site placements. Washington, DC: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security.

Wadwha, V., Rissing, B., Saxenian, A., & Gereffi, G. (2007a). Education, entrepreneurship and immigration: America’s new immigrant entrepreneurs, Part II. Kansas City, MO: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Wadwha, V., Saxenian, A., Freeman, R., & Gereffi, G. (2007b). America’s loss is the world’s gain: America’s new immigrant entrepreneurs (Vol. 4). Kansas City, MO: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Wadwha, V., Saxenian, A., & Siciliano, F. D. (2012). Then and now: America’s new immigrant entrepreneurs, Part VII. Kansas City, MO: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data presented in a forthcoming Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy Report, funded under contract SBAHQ-14-M-0106. Additional support was provided by the National Science Foundation’s Science of Science and Innovation Policy program, Grant No. 1355279.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blume-Kohout, M.E. Why are some foreign-born workers more entrepreneurial than others?. J Technol Transf 41, 1327–1353 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9438-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9438-3