Abstract

The goal of our study was to explore how first-generation immigrant/refugee Muslim women experience prayer and mindfulness in relation to their mental health. Participants were nine women from an urban city in the Midwestern USA. The women completed a structured demographic survey and a virtual semi-structured interview in a focus group. Using qualitative thematic analysis, we obtained four overarching themes from the data: (a) Prayer helps to build community, (b) Prayer promotes wellbeing, (c) Prayer increases faith, and (d) Prayer encourages intentional awareness. The findings demonstrate that prayer involves awareness and has a strong influence on the mental health of the women participants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to Mohamed (2018), about one percent of the total US populations are Muslims and more than half of them are immigrants. Although immigrant Muslim Americans tend to have better household incomes and higher level of education, Muslim Americans who seek mental health treatment experience a higher rate of adjustment disorders. Particularly for Muslim women, the challenges of acculturation, social discrimination due to wearing the hijab, and emotional trauma and fear for their safety are factors that affect their well-being (Mogahed & Chouhoud, 2017). In addition, religious discrimination was found to be associated with depression, anxiety, paranoia, and alcohol use (Hodge et al., 2016). Due to the social stigma, disclosure of mental illness has also been unfavorable. Oftentimes, Muslim women feel shame and fear about disclosing their mental health conditions, as such disclosures could jeopardize their marital prospects within the community (Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014). However, there are growing number of researchers who indicate that religious activities and rituals play a role of comfort and reflection when women immigrants experienced acculturative stress and psychological distress (Ibrahim & Whitley, 2021; Silva et al., 2017).

Despite experiencing prejudice based on their religion, religiosity and daily prayers have been shown to be the predictive factor for better well-being (Sayeed & Prakash, 2013; Pajevic et al., 2017). A substantial body of researchers has uncovered the benefits of religious practice on mental wellbeing (Albatnuni & Koszycki, 2020; Bonelli & Harold, 2013). The benefit of religious practice on mental wellness has various sources and dimensions including religious teachings for endurance, meditation, and social support. In addition, in Islamic history, mental wellbeing has gained considerable attention by Muslim scholars, such as Avicenna, Ghazali, and Al-Balkhi who have written treatises on the issue (Bonelli & Harold, 2013).

A good deal of these studies addresses the mindfulness aspect of worship in exploring its relation to psychological wellbeing. Mindfulness in Salah (prayer) means attention going only to Allah and a sense of pondering upon religious scripture (i.e., Holy Quran) (Ijaz et al., 2017). Many Muslims acknowledged the importance of prayers and its benefit to health and healing (Padela & Zaidi, 2018). Religious practices, such as Islamic Salah prayer and Jammat prayers, have both individual and collective meanings and benefits. The Salah prayer has stronger implications for mindfulness and a positive relationship with mental wellness (Saniotis, 2018; Sayeed & Prakash, 2013). In the religion of Islam, Salah prayer, and its components dhikr, where prayers are repeated and recited from the Quran, particularly in the mystical orientations, such as Sufism, mindfulness is an essential component of prayer and contemplation to appreciate God’s work and for consciousness (Kocak et al., 2012).

Current researchers draw on the ritualized body movements, such as yoga and Salah with their influence on reducing stress and anxiety (Sayeed & Prakash, 2013). In Islam, silent recitations and contemplation (Tafakkur) are at least as important as the ritualistic prayer and is encouraged. The therapeutic impact of these practices has been addressed in several studies on Muslims in general, for the purpose of fostering Muslim’s psychological health and mindfulness (Basit & Hamid, 2010; Mirdal, 2012; Unterrainer et al., 2014; Williamson, 2018). Meanwhile, Bartkowski et al. (2017) asserted that frequent Jammat (communal) prayer is correlated with an increased incidence of anxiety-related symptoms and recommended a qualitative investigation using in-depth or a focus group interview.

Although Muslim women engage in both Salah and Jamaat, there are limited research on their prayers experience and the effects of both prayer rituals on their well-being and healing process. Research on the relationship between prayer rituals and mental well-being was mainly conducted in other countries and are not specifically on first-generation immigrant/refugee Muslim women (Achour et al., 2021; Padela & Zaidi, 2018; Sayeed & Prakash, 2013). Our project aims to explore first-generation immigrant/refugee American Muslim women’s engagement with prayer and mindfulness in relation to their mental health, as they encounter higher rates of acculturation stress and are most vulnerable to social discrimination, depression, and anxiety (Hodge et al., 2016; Mogahed & Chouhoud, 2017). We explored these two dimensions: (a) Praying and mindfulness and their relation to American Muslim women’s experience as immigrants and refugees; (b) The manner in which the women claim private time and space through Salah as well as social space and group membership through Jamaat, especially after September 11 when American Muslim women are increasingly affiliated with religious institution (Mishra & Shirazi, 2010).

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study is to explore first-generation immigrant/refugee American Muslim women’s engagement with prayer and mindfulness in relation to their mental health. Review of the peer-reviewed research literature reveals a dearth of examination of Muslim women’s engagement in religious rituals from a mindfulness lens. The evidence of the relationship between religious rituals engagement and mindfulness/mental health remains lacking among this population. This pilot project addresses the following research questions: (a) What is the role of mindfulness in prayers of Muslim women toward their mental health? (b) What are Muslim women’s’ attitudes toward Salah prayers and Jamaat (communal) prayers in helping them cope with their circumstances as immigrants and refugees, including those related to claiming private time or group membership in religious affiliation? Through a qualitative research design, the project examines participants’ attitudes toward Salah and Jamaat (communal) prayers and the role of mindfulness in prayers.

Method

To adhere to the university’s safety measure for conducting research with human subject during the pandemic, we conducted the study in virtual format. After we obtained the university Institutional Review Board approval (HR—3594) for this study, potential participants were provided with an informed consent via email to learn more about the study procedure. Participants were informed that the study was voluntary; the participants would be in a focus group, and they had the option to withdraw at any point without any consequence. All participants in this study digitally signed a virtual consent form and sent it back to the research assistants via email before participation, were all notified that the study data they provided was confidential, and that any identifying information would be securely stored. All interviews were scheduled, conducted, and recorded via Microsoft Teams.

Participants

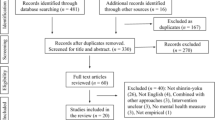

Participants were eligible to participate if they spoke English, identified as a first-generation immigrant or refugee Muslim, 18 years or older, and had access to technology that would accommodate remote video interviews. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling method (Houser, 2019) to select appropriate participants for this study. Three types of recruitment strategies were employed: (a) a snowball strategy by sending out an online recruitment flyer to Muslim community organizations or groups that have members that might be interested and met the study criteria, (b) posting the study recruitment flyers at the researchers’ social media site, and (c) asking leaders of Muslim community organizations or acquaintances who identified as Muslim to refer us to potential participants. Then, interested participants were screened by research assistants and subsequently invited to participate in the study. Braun and Clarke (2013) recommended sample size of 6–10 participants with 2–4 for focus groups in small projects. In addition, Fugard and Potts (2015) suggested that saturation of data can be obtained after as few as six interviews. In order to enhance and increase community-based research, we only recruited participants in the local community. Despite the attempts to reach as many women as possible who meet our inclusion criteria, a small number of participants consented to be part of the study. Nine women who identified as first-generation Muslims participated in our study, and most were married (67%) with a graduate degree (78%). All participants were assigned a study code to ensure confidentiality. Due to the small Muslim community in the Midwest region and the stigma of mental health in the community, the reports of the demographic characteristics were generalized to protect their privacy. Table 1 provides more details about our participants.

Procedure

We employed a focus group method to obtain participants’ unique perceptions about prayer, and to help understand how the participants understood their prayer experience in relation to mindfulness and mental health. Focus groups are culturally sensitive and an effective qualitative research methodology to collect small groups of participants’ opinions, perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and insights of their experiences (Kress & Shoffner, 2007). Two counseling graduate research assistants with experience and training in clinical interviewing techniques facilitated the focus groups using a semi-structured protocol and recorded the focus groups using Microsoft Teams. We believed the research assistants were appropriate for conducting interviews since they possessed many groups and individual counseling skills that can be effective in encouraging participants to engage in deep conversation (Kress & Shoffner, 2007). Each focus group lasted between 60 and 90 min with 2–3 participants in each virtual group; however, each participant only attended one focus group. Before joining the focus group and to reduce undue influence or pressure to agree to participate, each participant gave consent individually and was asked to complete a demographic questionnaire via Qualtrics. Each focus group was a one-time session and at the beginning of the session, participants were notified that the virtual focus group would be recorded and that they would be able to take a break as needed. Focus groups occurred during the week in the evening hours (between 3 and 5 pm) and there were no technical or connection difficulties.

During each focus group, the interviewers used a semi-structured interview to obtain responses from participants about their experiences with prayer and mindfulness in relation to mental health. Before conducting the interviews with the participants, the interviewers conducted a mock interview with each other to test the flow of the questions. During the interview, each participant was assigned a study code to maintain confidentiality (e.g., A1) and their responses were transcribed with the affiliated study code to identify participant voices. All virtual focus groups were conducted in private settings chosen by the participants. All participants stayed logged in to the focus groups for the duration of the groups, and participants were logged in from either their home or office. Two participants were driving during the focus group and one participant cooked for her family; however, participants were not interrupted by anyone during the sessions.

There were no repeated interviews conducted as the focus groups were conducted virtually. We were able to review the recording and obtained clear transcriptions after the interviews.

Researchers

According to Hunt’s (2011) guideline in publishing qualitative research, we present a “researcher-as-instrument" (Morrow, 2005, as cited in Hunt, 2011, p.2) paragraph so we can provide context for the study and the lens that we used to analyze the data. All authors are immigrants from different countries, and the first and third authors are first-generation immigrants. The first author is from Trinidad and Tobago. Her research focuses on how mindfulness-based interventions may improve wellbeing and quality of life. She uses both quantitative and qualitative research to study quality of life, to understand the impact of sexual violence and substance use, and to learn about the circumstances under which mindfulness-based interventions work for improved wellbeing and quality of life. The second author is a first-generation immigrant from Malaysia. Her research interests are rehabilitation counseling issues, multicultural counseling, refugees/immigrants with disabilities, and curriculum evaluation. The third author is a first-generation immigrant from Palestine. She is the founder of the Arab and Muslim Women’s Research and Resource Institute (AMWRRI) and serves as the President of AMWRRI Board of Directors. Her research focuses on women’s identities, gender power relations, and body politics and gendered disability in the contexts of cultural encounter.

Measures

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire to provide information about their age, marital status, education level, number of hours worked per week, occupation, homeland country/city/town/village, year immigrated to the USA, other countries of residence prior to moving to the US, ethnic identity, and language(s) spoken at home. The interview questions were drafted, discussed, and finalized based on a comprehensive literature review conducted by the researchers. The questions were also informed by the observations and informal discussion with Muslim women by the third author who is a community leader in the area. The interview questions were written and communicated in English. The following topics were covered in the semi-structured interview questions for the focus group:

-

Praying rituals: Questions included: “tell us about your experience praying individually,” “what is your individual praying routine?” and “what are the types of prayer or religious activities you engage in, individually?”.

-

Community Praying: Questions about praying in the Mosque included: “How regular do you attend the Mosque?” “Tell us about community praying,” and “What are the reasons you go to the Mosque?”.

-

Mindfulness in Prayer: Questions about attention and awareness during prayer included: “Describe your prayer rituals,” “What do you pay attention to when you pray?” “What happens when you pray with full attention?” and “What do you do during prayer that is helpful to be attentive to God?”.

-

Relationship Between Prayer and Mental Health: Questions about prayer and difficulties in life included: “What challenges have you faced as a first-generation Muslim in the USA?” “How do those challenges affect your mental health?” And “In what ways do you see prayer as being effective in managing your mental health?”.

The interview guide and the sample questions are presented in Table 2.

Data Analysis

A thematic analysis was utilized. Thematic analysis is useful when examining various perspectives to highlight similarities and differences among participant voices (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Focus groups were video recorded and transcribed verbatim by interviewers. Since the focus groups were recorded, the interviewers did not take the field notes. The recordings were reviewed for transcriptions, data quality, and analysis following the guidelines by Flynn et al. (2018). Transcriptions were stored in a password protected folder shared by the researchers and interviewers. Four researchers (first and second author and two interviewers) who comprised the data analysis team met to review coding and data analysis procedures. Before coding, the data analysis team reviewed one focus group transcription individually then collectively to identify initial ideas for coding. Then, all data were systematically coded individually and collectively by reviewing the data several times using an inductive process.

To ensure the trustworthiness in our evaluation and to adhere to the American Psychological Association Taskforce’s recommendations on attending to methodological integrity within our work, the data analysis team engaged in consistent dialogue and reflection about the data to bracket any perceptions about it. One of the researchers audited the findings by reviewing all transcriptions and the analysis. We met multiple times to review the data and themes using constant comparison (Levitt et al., 2017; Minton & Lenz, 2019). Since thematic analysis is subjective, after several rounds of coding, the data were sent to the auditor (third author) for review. The auditor provided some suggestions and other interpretations of the data for consideration by the data analysis team. The data analysis team then met to review the auditor’s feedback and came to consensus about the themes.

Results

Our results consist of four overarching themes from the data: (a) Prayer helps to build community, (b) Prayer promotes wellbeing, (c) Prayer increases faith, and (d) Prayer encourages intentional awareness. The themes and example of quotations are presented in Table 3.

Prayer Helps to Build Community

Prayer can be a personal practice. The function of a mosque in diaspora can be different for women to engage in when they immigrate to another country. For example, it is not necessary for women to attend a Mosque; communal prayer can be a way to create community with others outside of the home setting. Participants shared their experiences praying with family and loved ones, and with others in their community and the Mosque, which helps to foster closeness and a sense of togetherness among everyone. One woman shared that prayer “helps you appreciate everyone” and that prayer “helps you understand that we are all in this together.” The same woman shared that prayer “reminds you of a sense of family or community. It helps you to appreciate everyone that you are surrounded with because there is a lot of family and friends around.” Praying with family can also be a way of creating a community within your home that reflects values among family members. Praying with family members, especially across different generations, can be a way to pass on family and cultural traditions. One woman shared “I want my children to see me when I am praying, and as soon as I start praying, they start praying too. I want to be a role model for them.”

Prayer Promotes Wellbeing

There was a central focus around prayer, both individual prayer and collective prayer, as a means of preserving and maintaining mental health which positively contributes to wellbeing. For our participants, prayer was an important coping skill for life stressors and challenges and was discussed as a normal part of their routine for managing emotional distress. One woman shared “if I am distressed, I choose a verse that can really help me refocus. There are chapters or verses from the Quran that are fitting to the situation I am in.” Another woman shared that “It gets really stressful, but then just knowing that at the end of the day, especially adding those two prayers before I go to sleep, just like sitting down just thanking God for everything and just asking him for everything like—there is like a list I got down there—where it is like this, this and this. And thank you for this, this and this. It really does help, it really.”

Additionally, our participants shared that praying in the Mosque or with family is one way to stay focused on the positive aspects of life despite daily stressors. The participant shared that “a lot of times I find myself going to the mosque after I take a big exam or before my exams. I find myself there a lot. Especially because it is super stressful. It really helps me to destress and when I do go to the Mosque, I do find my prayers a lot more focused if that makes sense.” Prayer also helps to increase feelings of hopefulness and optimism. The participant also explained that “the biggest thing is that [prayer] helps remind me that at the end of the day everything is going to be okay.”

Prayer Increases Faith

During challenging times, prayer is a way to communicate with and increase trust in God. One woman shared:

“So many things in my life, and God has brought me so safely from those things that at one time I thought I had lost. Now what will happen to me? How will I get out from [under] these things? I would, but then inside my heart my faith was so powerful, that is strength. It is God’s thing. He is when he brought this thing he is going to take you away from these two and he did. Alhamdulillah. He saved me all from the bad things, which was seen like an unsolvable. There was no way, I was all totally in dark, but there was a light of hope - that God is there. He is going to take you from these things and he did. I am so happy for that. All praise to God.”

Participants described that through reading the written word (e.g., in the Quran) and prayer they can stay focused and reconnect with their faith in God. One woman explained that “we can read any part of the Quran during our Sa’laat. I choose a verse that can really help me refocus and remember that what sister said, Allah only gives us what we can handle, and life is full of trials and He knows what is best for me even if I may not feel it.”

Prayer Encourages Intentional Awareness

Participants discussed how they prepare themselves for prayer and the importance of mindful awareness during prayer as they connect with God. One woman shared that “by prayer you are meditating. You clean yourself, soul, mind, spirit, body from all bad things, it is like washing away things, like from detergent, you wash something so prayer is like this thing that is cleaning you from inside everything, if you are praying fully and scripturally.” Another woman explained that praying is a personal way to connect with God, she shared, “Praying for me personally is a connection with my creator five times a day, and to kind of forget about all the worldly problems during that time and just focus on my connection. To me prayer is a direct connection with your creator and to me is a form of deep meditation and just letting myself go and get away from the problems of the world for a little bit.”

For some women, the act of praying can be a meditation, with minimal distractions to encourage an environment of reverence and complete focus. One woman shared that “prayer is very important, so I try to limit my distractions. I put my pager on silent mode and everything.” There is also an intentional practice of focusing during prayer. One woman explained, “I think about every single word that I am saying and then I just take a deep breath while I am reciting it. That is when I am really taking more time to really relax on my prayer.”

Discussion

This study provides evidence that mindful prayers have served as essential coping strategies for first-generation immigrant and refugee Muslim women during the trying time, such as pandemic. Although National Health Interview Survey has excluded prayers as a complementary and integrative health modality (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2020), this study concurred with other studies that prayer rituals are an important complementary and culturally responsive approach for minority communities (Albatnuni & Koszycki, 2020; Ijaz et al., 2017; Watson-Singleton et al., 2019). We discovered four themes from this study describing the meaning of participants’ experience of Muslim prayers and its relationship with mental health. Overall, the Muslim women’s prayers experiences not only involve horizontal and vertical connection, where the participants built a sense of connection with the community and God (Webster, 2017); it also expanded into participants’ inner self that facilitate the sustainability of their well-being. In this study, the meaning of Muslim women’s prayer experiences can be described in different dimensions (a) build community which signifies horizontal connection with people around them; (b) increases faith which emphasize the vertical relationship with God; (c) promotes mental wellbeing, and (d) encourages intentional awareness/mindfulness, which draw them to their inner self.

The participants revealed the benefits of communal prayers that brings them a sense of community. It concurred with the assertion that religious practice has a positive effect on individuals’ mental wellness in different dimensions, such as social support (Boneli & Harold, 2013). Our study added additional evidence that communal prayers are platforms for the women to build their community. The community has helped them to gain emotional support that enhanced their well-being. While experiencing hostility in the public arena makes it difficult for American Muslims to develop a robust communal life, this community signifies the communal solidarity and can serve as a health-promoting focal point (Padela & Curlin, 2013).

Researchers have demonstrated evidence of the benefit of communal prayers in promoting positive social/congregational support, a sense of belonging, and psychological well-being (Albatnuni & Koszycki, 2020). This study also highlighted the sense of empowerment that women have when they pray. They felt empowered by being a role model for the younger generations in their faith and mental health promotion. This is congruent with Speed et al. (2018) where they asserted that having a purpose of life is strongly linked to high quality of subjective well-being. The participants in our study maintained their well-being by being a role model to fulfill their purpose of life.

The participants further confirmed how prayers helped to increase their trust in God during the trying times, especially during the pandemic. Through communication with God or reading God’s word, the women developed their fortitude and their sense of hope. Through prayers, the women demonstrated their reliance on God as a source of power and intervention (Shaw et al, 2019). These practices and their trust in God were directly linked to positive mental health including providing participants with assistance in coping, peace, and well-being (Albatnuni & Koszycki, 2020; Berzengi et al., 2017; Koenig et al., 2012).

Through the individual and collective prayers, the participants in this study experienced prayers as an essential coping strategy while navigating stressful life situations. It has been documented that daily prayers have been a consistent predictor in well-being promotion (Sayeed & Prakash, 2013; Pajevic et al., 2017). Ibrahim and Whitley (2021) asserted that both private and public religiosity can be a constant resource for resilience, and mental health promotion where private prayers, such as reading the Qur’an can provide ontological security during difficult life situations and transitions.

Beyond private and public religious prayers, the participants’ prayers went deeper into eliciting individuals’ insights, awareness, and mindfulness that facilitated a sense of well-being. The participants experienced increased awareness of their connection with God while praying and meditating. The participants found their strengths in facing challenges in their daily life during the pandemic through these intentional mindfulness prayers. In investigating the relationship between spirituality/religiosity and subjective well-being, Villani et al. (2019) found that individuals who perceived to have innerness (i.e., inner strength) were linked to decreased negative experience. Although mindfulness has traditionally been inspired by Buddhism (Kang & Whittingham, 2010), Muslim prayers also have some form of mindful awareness. Mirdal (2012) pointed out that Jalal al-Din Rumi’s poem ‘The Guesthouse’ has highlighted the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) ideas of cultivating acceptance and how to ‘bring a gentle, curious awareness to their thoughts, feelings and physical reactions during the experience, allowing them to “be,” “awareness of breathing,” and “gaze on the steps.” Besides, according to Albatnuni and Koszycki (2020), intentional awareness during prayer has been an important part of Muslim forms of prayers, which has a positive association with well-being. Furthermore, Isgandarova (2019) proposed using “Muraqaba” as a mindfulness-based therapy in Islamic psychotherapy.

To bridge the concepts of mindfulness from the Islamic perspective, these points are evidenced: (a) ‘Khushū”(humility and peace of mind during prayer) where the presence of mind is seen as a highly recommended component to prayer and the ritual is in an autopilot mode (Thomas et al., 2016), (b) Mindfulness is routine daily activities where devotional litanies and supplication from the Islamic tradition undertaken before, during and after routine activities (Hodge & Nadir, 2008), (c) Focusing on the Prophetic traditions in responding to stressors with conscious awareness rather than reacting to one’s own emotions (Malinowski, 2013), and (d) Sabr/patience where it has been highlighted in the Quran and as an Islamic virtue (Mirdal, 2012).

Implications

Ibrahim and Whitley (2021) asserted that health professionals can utilize Islamic religiosity or spirituality to foster effective recovery in patients or clients where appropriate. Moreover, Miller and Chavier (2013) reported that therapists have been successfully integrating prayers in the therapeutic process while maintaining ethical boundaries. Collaboration with the Muslim community centers and religious leaders are beneficial for providing holistic care for the Muslim community. Basit and Hamid (2010) also urged that mental health professionals provide effective services by conducting proactive outreach and culturally sensitive therapeutic interventions.

In terms of promoting community-based mindfulness approach, Mirdal (2012) asserted that Rumi’s teachings in the Muslim community seem to be an appropriate alternative where it highlighted the commonality of mindfulness-based therapies. Rumi's religious philosophy can constitute a meaningful alternative to Buddhist-inspired practices in the transcultural community agencies or settings, especially in encounters with clients or patients with a Muslim background. Similar to using Christian prayers as a form of meditation that are linked to a higher level of wellness, Muslim mindful prayers can be a complementary and culturally responsive approach for mental health relapse prevention (Ijaz, et al., 2017; Knabb, 2012).

Study Limitations

While Mohamed (2018) indicated that about one percent of the total US populations are Muslims and more than half of them are immigrants, the sample size of our study is extremely small. Moreover, our study was location specific with all of them mainly living in a metropolitan city in the Midwest. Therefore, the participants in our study are not a full representation of the immigrant Muslim population in the USA. Experiences of Muslim women in other regions of the country should be explored. In addition, this study acknowledges the lack of diversity within the Muslim women community. Future research among Muslim women who are African/Black American, Southeast Asians, and South Asians are warranted to enrich the knowledge of their unique strengths, fortitude, and their challenges. Due to the COVID-19 safety measures, the focus groups were switched to a virtual format. Although there are pros in conducting virtual focus groups (such as no traveling), we acknowledge the challenges of internet glitches, distraction, and confidentiality issues. We also acknowledge that the circumstances of the pandemic may have contributed to the limited interest in participating in this study. We recommend that future researchers consider learning more about how first-generation immigrant/refugee Muslim women engage with prayer and mindfulness post-pandemic.

We also acknowledge that a virtual setting limits the unique and personal interactions among and between participants and the interviewer. In addition, while interviewers were fortunate to see the participants in their natural environment and were able to read facial expressions, the interviewers also had limited opportunities to see other non-verbal expressions (e.g., restless feet), which may have provided more context to the discussions.

Our interviewers were White women who were not Muslim or immigrants. Although a non-Muslim interviewer can add an objectivity and serve as a neutral medium in data collection, many deeper insights might not be able to solicit due to the ignorance of the content. Only one interviewer conducted the focus groups and while we recognize that this led to a more intimate discussion as the groups were small, we also believe an additional interviewer would be helpful for taking additional notes and making other observations during the focus groups. Our participants were also located in the same region, which can add some context to that geographical location. However, participants in other urban and rural areas could provide more diverse experiences.

Lastly, although we conducted four focus groups with 2–3 members in each group, during the blind coding, we happened to select most of the exemplars from the same person in each group. For future research, multiple voices should be captured in a focus group.

Conclusions

We discovered four overarching themes from the data that we collected during the pandemic: (a) Prayer helps to build community, (b) Prayer promotes wellbeing, (c) Prayer increases faith, and (d) Prayer encourages intentional awareness. Consistent with research evidence that daily prayers have been a strong predictor in well-being promotion, this study also found that the individual and collective prayers have been an essential coping strategy while navigating stressful life situation. There were three different dimensions to women’s prayer experiences: (a) horizontal that connect them with the community, (b) vertical that strengthen their relationship with Allah, and (c) self-innerness where they found their inner strengths and mindfulness in promoting well-being. To increase a higher level of wellness among Muslim women, Islamic mindful prayers can be a complementary and culturally responsive approach for mental health relapse prevention. Furthermore, collaboration with the Muslim community centers and religious leaders are beneficial to provide holistic care for the Muslim community. Future research among Muslim women who are African/Black Americans, Southeast Asians, and South Asians are warranted to enrich the knowledge of their unique strengths, fortitude, and their challenges. Lastly, we conducted the focus groups in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. A similar research study during a non-pandemic period is warranted.

References

Achour, M., Muhamad, A., Syihab, A. H., Mohd Nor, M. R., & Mohd Yusoff, M. Y. Z. (2021). Prayer moderating job stress among Muslim nursing staff at the University of Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC). Journal of Religion and Health, 60, 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00834-6

Albatnuni, M., & Koszycki, D. (2020). Prayer and well-being in Muslim Canadians: Exploring the mediating role of spirituality, mindfulness, optimism, and social support. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(10), 912–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1844175

Bagasra, A., & Mackinem, M. (2014). An exploratory study of American Muslim conceptions of mental illness. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 8(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0008.104

Bartkowski, J. P., Acevedo, G. A., & Loggerenberg, H. V. (2017). Prayer, meditation, and anxiety: Durkheim revisited. Religions, 8(9), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8090191

Basit, A., & Hamid, M. (2010). Mental health issues of Muslim Americans. The Journal of Islamic Medical Association of North America, 42(3), 106–110. https://doi.org/10.5915/42-3-5507

Berzengi, A., Berzenji, L., Kadim, A., Mustafa, F., & Jobson, L. (2017). Role of Islamic appraisals, trauma related appraisals, and religious coping in the posttraumatic adjustment of Muslim trauma survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000179

Bonelli, R. M., & Harold, G. K. (2013). Mental disorders, religion, and spirituality 1990 to 2010: A systematic evidence-based review. Journal of Religion and Health, 52, 657–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9691-4

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

Flynn, R., Albrecht, L., & Scott, S. D. (2018). Two approaches to focus group data collection for qualitative health research: Maximizing resources and data quality. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917750781

Fugard, A. J., & Potts, H. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1005453

Hodge, D. R., & Nadir, A. (2008). Moving toward culturally competent practice with Muslims: Modifying cognitive therapy with Islamic tenets. Social Work, 53(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/53.1.31

Hodge, D. R., Zidan, T., & Husain, A. (2016). Depression among Muslims in the United States: Examining the role of discrimination and spirituality as risk and protective factors. Social Work, 61(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swv055

Houser, R. (2019). Counseling and educational research: Evaluation and application (4th ed). Sage Publications.

Hunt, B. (2011). Publishing qualitative research in counseling journals. Journal of Counseling and Development, 89(3), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00092.x

Ibrahim, A., & Whitley, R. (2021). Religion and mental health: A narrative review with a focus on Muslims in English-speaking countries. Bjpsych Bulletin, 45, 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.34

Ijaz, S., Khalily, M. T., & Ahmad, I. (2017). Mindfulness in Salah Prayer and its Association with Mental Health. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(6), 2297–2307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0413-1

Isgandarova, N. (2019). Muraqaba as a mindfulness-based therapy in Islamic psychotherapy. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(4), 1146–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0695-y

Kang, C., & Whittingham, K. (2010). Mindfulness: A dialogue between Buddhism and clinical psychology. Mindfulness, 1(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0018-1

Knabb, J. J. (2012). Centering prayer as an alternative to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression relapse prevention. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 908–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9404-1

Kocak, M. Y., Göçen, N. N., & Akin, B. (2012). The effect of listening to the recitation of the Surah AlInshirah on labor pain, anxiety and comfort in Muslim women: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01356-w

Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Kress, V. E., & Shoffner, M. F. (2007). Focus groups: A practical and applied research approach for counselors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 85(2), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00462.x

Levitt, H. M., Motulsky, S. L., Wertz, F. J., Morrow, S. L., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2017). Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology Promoting methodological integrity. Qualitative Psychology, 4(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000082

Malinowski, P. (2013). Flourishing through meditation and mindfulness. In I. Boniwell, S. A. David, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Happiness (pp. 384–396). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557257.013.0030

Miller, M. M., & Chavier, M. (2013). Clinicians’ experiences of integrating prayer in the therapeutic process. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 15(2), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2013.776441

Minton, C. A., & Lenz, A. S. (2019). Practical approaches to applied research and program evaluation for helping professionals. Taylor & Francis Group.

Mirdal, G. M. (2012). Mevlana Jalāl-ad-Dīn Rumi and mindfulness. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(4), 1202–1215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9430-z

Mishra, S., & Shirazi, F. (2010). Hybrid identities: American Muslim women speak. Gender, Place and Culture, 17(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663691003600306

Mogahed, D., & Chouhoud, Y. (2017). American Muslim poll 2017: Muslims at the crossroads. Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/American-Muslim-Poll-2017-Report.pdf

Mohamed, B. (2018). New estimates show U.S. Muslim population continues to grow. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/03/new-estimates-show-u-s-muslim-population-continues-to-grow/

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). (2020). Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name

Padela. A. I., & Zaidi. D. (2018). The Islamic tradition and health inequities: A preliminary conceptual model based on a systematic literature review of Muslim healthcare disparities. Avicenna Journal of Medicine, 8(1), 1–13. https://www.thieme-connect.de/products/ejournals/pdf/https://doi.org/10.4103/ajm.AJM_134_17.pdf

Padela, A. I., & Curlin, F. A. (2013). Religion and disparities: Considering the influences of Islam on the health of American Muslims. Journal of Religion and Health, 52, 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9620-y

Pajević, I., Sinanović, O., & Hasanović, M. (2017). Association of Islamic prayer with psychological stability in Bosnian war veterans. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(6), 2317–2329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0431-z

Saniotis, A. (2018). Understanding mind/body medicine from Muslim religious practices of Salat and Dhikr. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(3), 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9992-2

Sayeed, S. A., & Prakash, A. (2013). The Islamic prayer (Salah/Namaaz) and yoga togetherness in mental health. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(Suppl 2), S224–S230. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.105537

Shaw, S. A., Peacock, L., Ali, L. M., Pillai, V., & Husain, A. (2019). Religious coping and challenges among displaced Muslim female refugees. Affilia, 34(4), 518–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109919866158

Silva, N. D., Dillon, F. R., Verdejo, T. R., Sanchez, M., & De La Rosa, M. (2017). Acculturative stress, psychological distress, and religious coping among Latina young adult immigrants. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(2), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017692111

Speed, D., Coleman, T. J., III., & Langston, J. (2018). What do you mean, “What does it all mean?” Atheism, nonreligion, and life meaning. SAGE Open, 8(1), 2158244017754238. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017754238

Thomas, J., Raynor, M., & Bakker, M. C. (2016). Mindfulness-based stress reduction among Emirati Muslim women. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 19(3), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1168389

Unterrainer, H., Andrew, J. L., & Andreas, F. (2014). Religious/spiritual well-being, personality and mental health: A review of results and conceptual issues. Journal of Religion and Health, 53, 382–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9642-5

Villani, D., Sorgente, A., Iannello, P., & Antonietti, A. (2019). The role of spirituality and religiosity in subjective well-being of individuals with different religious status. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01525

Watson-Singleton, N. N., Black, A. R., & Spivey, B. N. (2019). Recommendations for a culturally responsive mindfulness-based intervention for African Americans. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 34, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.11.013

Webster, J. (2017). Praying for salvation: A map of relatedness. Religion, 47(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1225905

Williamson, W. P. (2018). The experience of Muslim prayer: A phenomenological investigation. Pastoral Psychology, 67(5), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-018-0831-3

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all women who participated in this research study. We thank Dr. Jerome Holzbauer for his comments and edition that greatly improve this manuscript. We would like to share our gratitude to Julia Pawlowski and Leah Witthuhn for assisting us in collecting data.

Funding

This study was supported by Marquette University Institute for Women’s Leadership Summer Pilot Grant program (06-09845-80801). It was approved by Marquette University Internal Review Board (Protocol Number HR-3594).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Callender, K.A., Ong, L.Z. & Othman, E.H. Prayers and Mindfulness in Relation to Mental Health among First-Generation Immigrant and Refugee Muslim Women in the USA: An Exploratory Study. J Relig Health 61, 3637–3654 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01600-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01600-x