Abstract

The aim of this review was to explore the evidence surrounding patients and families’ expression of spirituality, spiritual needs or spiritual support within healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of nursing practice. While there is a plethora of research and publications related to COVID-19 and there are reports of increasing attention to nurses’ psychological distress, there is little understanding of experiences related to patients’ expression of spirituality, spiritual needs or spiritual support within healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. A scoping review was conducted to search and select potential studies and undertake data extraction and synthesis. Twenty-one studies published between March 2020 and August 2021 were identified. Themes and subthemes that emerged from analysis of the studies included spiritual needs, new awareness of spiritual needs and spiritual interventions, chaplaincy referrals, and improved well-being. The potential requirement for spiritual care during these times has anecdotally never been greater. At the same time the existent ethical challenges persist, and nurses remain reticent about the topic of spirituality. This is evident from the clear lack of attention to this domain within the published nursing literature and a limited focus on spiritual care interventions or the experiences and spiritual needs of patients and their families. Greater attention is needed internationally to improve nurses’ competence to provide spiritual care and to develop and advance nursing and research practice in the field of spiritual care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spiritual support within healthcare has had a long and distinguished history (Swift, 2014). Steeped within religious traditions, western healthcare has been systematically uncoupling from these traditions in keeping with growing secularism within the context of modern societies (Nissen et al., 2021). However, healthcare chaplaincy and pastoral care services, which arose from this legacy, remain intrinsic to the provision of healthcare across societies at large, for the simple reason that people require this support.

Religious organisations, often the founders of nursing programmes or philanthropic providers of healthcare services, have less influence in today’s modern healthcare environment. Healthcare chaplaincy and pastoral care services are emerging as a professional service, increasingly multifaith (Brady et al., 2021), that support patients, families and staff (Tata et al., 2021). While there are some legacy issues that continue to raise concerns, in some jurisdictions, including the presence of Christian iconography and chapels within healthcare settings and indeed challenges to the need for chaplaincy services (Swift, 2014, TheJournal.ie, 2013; Medical Independent, 2013; National Secular Society, 2009), the benefits of or requirements for spiritual support in healthcare are reported by people of all faiths, and none, and there is increasing attention paid to the spiritual aspects of care even within highly secular countries (La Cour & Hidvt, 2010).

End-of-life care decisions (Clyne et al., 2019; Tata et al., 2021), for example, and attitudes to death and dying (Thauvoye et al., 2020) are often profoundly embedded in personal and cultural beliefs, and addressing spirituality can serve to support end of life in a positive way (deVries et al., 2019). The healthcare chaplain and pastoral care workers therefore have a key role in spiritual support in healthcare across the spectrum of illness experiences (Nuzum, 2016; Nuzum et al., 2021), and where this facility is available, they are the specialists in spiritual support for patients and their families.

At the same time, there is a growing interest in spiritual care provision by nurses across the globe (Fang et al., 2022; van Leeuwen et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2016). Indeed, there are moves internationally for spiritual care and spiritual support to form part of the nurse’s role, most recently elucidated within the European Erasmus Plus Project- Enhancing Nurses and Midwives' Competence in Providing Spiritual Care through Innovation, Education and Compassionate Care (EPICC, 2021). The latter provides clear guidance for nurses to support patients’ spirituality, through the identification of four distinct nursing competencies: (i) intrapersonal, interpersonal and spiritual care assessment, (ii) planning, (iii) spiritual care intervention and (iv) evaluation perspectives. These competencies support the nurse’s awareness of their own spirituality in order to be able to comprehensively assess spiritual care needs and provide spiritual care interventions (EPICC, 2021). These activities are carried out in close collaboration with healthcare chaplains, where relevant, as referral to chaplains or pastoral care services are a key feature within these competencies. For nurses, EPICC define spirituality as:

“The dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant and/or the sacred” (EPICC, 2021)

While there is growing interest in the nurse’s role in the provision of spiritual support (van Leeuwen et al., 2021), one would expect this to have been reflected and indeed exacerbated in the literature during the COVID-19 pandemic. While new ways of providing end-of-life care and other types of care certainly emerged (Bowers et al., 2021), and from the public’s perspective spirituality seemed to have become increasingly valued (Papadopoulos et al., 2020), it is important to know whether or not supporting spiritual needs by nurses increased within this context and what support patients and families required.

Given the perceived importance of spiritual care, this area would likely receive some attention during a crisis point in healthcare and within individual’s lives. To address this gap, we performed a scoping review to explore the spiritual support of patients and families during COVID-19 from the perspective of nurses.

Aim of the Review

The aim of this scoping review was to examine the literature exploring healthcare patients’ and families’ experiences of spirituality, spiritual needs or spiritual support within healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Spirituality is understood as a dimension of personal life that enables the expression and seeking of meaning, the value of connectedness and for some, transcendence (EPICC, 2021; Weathers et al., 2016).

Methods

A scoping review was conducted in order to explore the nature of current evidence (Armstrong, 2011; Peters et al., 2020). The review primarily focussed on literature from March 2020 to March 2021, reflecting the early outset of the COVID-19 pandemic (although no exclusionary dates were applied to the search).

Identifying the Relevant Studies

The search strategy was based on clear search terms listed in Table 1 and further refined by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Database searches were undertaken in CINAHL, Medline, Atla Religion Database with Atla Serials Search terms.

Study Selection

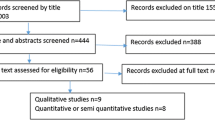

Both researchers screened all titles and abstracts and undertook full-text review. The results are reported using a PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., 2021a) (Fig. 1).

PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021b)

Charting the Data

One researcher undertook preliminary data extractions using a standardised form to chart the data. This was later confirmed by the second researcher. Study design, population, sample size, setting, conduct, findings and reported limitations were considered. Information on interventions was extracted where appropriate. Both researchers reflected on the quality of the studies included. Quality appraisal using specified criteria was not undertaken as this was a scoping rather than a systematic review (Munn et al., 2018). Thematic analysis was undertaken using a three-step approach of firstly coding the material and then identifying themes and finally constructing a thematic network (Dhollande et al., 2021). Initial coding provided the opportunity to highlight text, into phrases and sentences. Coding provides a condensed version of the main points and common meanings that occur in the data (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The codes created were then reviewed and patterns identified which when taken together enable the generation of themes. The constructed thematic networks summarise the main themes and are linked back to the aim of the review (Schellekens et al., 2020).

Findings

Selection of Studies

The search yielded 233 records (Fig. 1). Three duplicates were removed. Following title and abstract review 195 records were excluded. Key reasons for exclusions were lack of relevance and incompatibility with the study aims and scope. Thirty-five studies underwent full full-text review, 14 were excluded, mainly because these did not fully meet the inclusion criteria. Twenty-one studies were ultimately included in the review.

Description of the Studies

Of the 21 studies (Table 3), five were qualitative, with three using case study method (Drummond & Carey, 2020; Gray-Miceli et al., 2020; Rentala & Ng, 2021) and two used content analysis of interview data from nurses (de Diego-Cordero 2021; Galehdar et al., 2020). Two studies were quantitative (Giffen & MacDonald, 2020; Umucu & Lee, 2020). Nine studies were commentaries based on personal reflections of experiences during COVID-19, (Bakar et al., 2020; Finiki & Maclean, 2020; Geppert & Pies, 2020; Hashmi et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2021; Pies, 2020; Rathore et al., 2020; Roman et al., 2020Sanchetee & Sanchetee, 2020). Of the remaining five studies, three were either editorials or letters to the editor (Dein et al., 2020; Heidari et al., 2020; Wiederhold 2020), one was reported by the authors as a ‘quick review’ (Rao et al., 2020) and one study provided a position statement (Damani et al., 2020). None of the studies involved interventions.

Generation of Themes

Following an analysis of the extracted data, two main themes and five subthemes emerged from analysis of the studies: spiritual needs, including additional spiritual needs in the context of COVID-19 and new awareness of spiritual needs; and spiritual interventions, including some novel interventions, chaplaincy referral and improved well-being.

Spiritual Needs

All of the studies demonstrated awareness of the significance of spirituality in healthcare. A number of the studies highlighted the increased reported significance of spiritual needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the significant role that healthcare chaplains and nurses played in providing spiritual care, in the form of presence and prayer and ensuring that meaningful spiritual objects were provided to patients as needed (Bakar et al., 2020; de Diego-Cordero et al., 2021; Geppert & Pies, 2020; Rathore et al., 2020). It is important to note that three of these papers (Bakar et al., 2020; Hashmi et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2021) are based on both personal experience of providing frontline care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other studies demonstrated a new awareness of spiritual needs particularly those associated with COVID-19 pandemic (Drummond & Carey, 2020; Gray-Miceli et al., 2020; Hashmi et al., 2020). This new awareness was highlighted by de Diego-Cordero et al. (2021) study of nurses working in the critical care setting, where nurses saw the value of spiritual care in helping patients deal with their diagnosis of COVID-19 but viewed their limited education on the topic and lack of time as barriers to providing this care. These findings were also highlighted by Drummond and Carey (2020) and Gray-Miceli et al. (2020) studies, both conducted in older care centres, where the lessening of socialisation and the impact of isolation on patients/residents, staff and families during COVID-19 was explored.

In an opinion piece, Hashmi et al. (2020) suggest the need to recognise the collaborative role that spiritual care providers, such as healthcare chaplains and pastoral care workers have in ensuring that religious bias is avoided and spiritual care is embedded in the holistic care provided to patients, particularly in a time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Spiritual Interventions

Spiritual care is considered within the context of holistic nursing care. A number of the included studies make reference to spiritual interventions, and in some cases, novel interventions to support spiritual care are identified (Pierce et al., 2021; Pies, 2020; Rathore et al., 2020; Rentala & Ng, 2021). Pierce et al. (2021) spoke from their experience of providing spiritual care in the emergency department. They highlighted a new approach to providing spiritual care through the use of an algorithm for spiritual care provision in the event of termination of resuscitation during the pandemic.

Pies (2020) in his opinion piece, suggests that for some who do not embrace spiritual or religious practice, solace may be found in the therapeutic use of music, poetry or literature. Based on findings from their case study, Rentala and Ng (2021) suggest the use of integrative mind–body-spirit approach as a novel way to promote spiritual well-being and maybe helpful in providing insight to nurses working in mental health services of the importance of including psycho-social-spiritual interventions. Recognising the relationship of body-mind-spirit has the potential to facilitate a more holistic approach to care that promotes not just physical but also spiritual well-being (Rentala & Ng, 2021).

A number of the studies included in this review indicated the effect that spiritual care had on increased hope, resilience and well-being (de Diego-Cordero et al., 2021; Finiki & Maclean, 2020; Galehdar et al., 2020; Rao et al., 2020; Roma et al., 2020; Umucu et al., 2020; Wiederhold, 2020). While this effect is for the most part based on personal opinions of the authors, Galerhar et al. (2020) and Umucu et al. (2020) based their findings from studies involving nurses and patients, respectively. Galehdar et al. (2020) indicated that provision of spiritual care had a positive impact by reducing stress and improving feelings of wellness in patients cared for by nurses in Iran, while Umucu et al. (2020) found that spiritual care increased hope and resilience and ultimately improved well-being.

Finiki and Maclean (2020), Rao et al. (2020), Roma et al. (2020), and Wiederhold (2020) in their opinion pieces all supported this view. Giffen and MacDonald (2020) in reporting of the findings on spiritual care during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that access to healthcare chaplaincy was important due to the significant role that they played supporting patients and families during the various stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Giffen & MacDonald, 2020).

Discussion

Spirituality is understood as fundamental aspect of humanity that relates to belonging, finding personal meaning, peace and a sense of connection to others (Coppola et al., 2021). While spirituality and fulfilling spiritual needs are not necessarily associated with religion, some will express their spirituality in this way (Coppola et al., 2021; Weathers et al., 2016). This review found that while spiritual needs were perceived as important, is it notable that much of the literature is from the perspective of the nurse, or healthcare chaplain, rather than the patient or family, and much of this is anecdotal. However the provision of spiritual objects remained important for some (Bakar et al., 2020; de Diego-Cordero et al., 2021; Geppert & Pies, 2020; Rathore et al., 2020), although caution was advised in terms of ensuring that spiritual care remains sensitive to faith and non-faith requirements (Hashmi et al., 2020).

This support through the provision of spiritual objects was interesting, as spirituality and religiosity are often shaped and influenced by culture (Murgia et al., 2020), and individuals’ experiences (Nascimento et al., 2016). Providing person centred spiritual care can be an important dimension of dignified care in multicultural contexts (Cheraghi et al., 2014). Indeed, it is found that people find solace in rituals, conversations, and attention, provided by pastoral care workers and healthcare chaplains (Brady et al., 2021). Indeed, Imber-Black (2020) has recently identified how families and communities preserved and developed religious and other rituals to connect during COVID-19.

Certainly spiritual support with or without belief in God can give people a sense of meaning, and help with coping, especially at the end of life (Clyne et al., 2019, Nuzum et al., 2021), and nurses have been encouraged to provide spiritual support (Clarke, 2013). However, addressing spirituality within healthcare settings is not a straightforward issue, given the complexities and diverse spiritual (and non-spiritual) beliefs and practices that exist. While evidence from research indicates that spirituality has the potential to support optimal health (Peteet et al., 2018), since it is strongly associated with well-being (Forlenza & Vallada, 2018), higher quality of life and psychosocial experience (Koenig et al., 2012; Labrague et al., 2016), this review found that nurses still lack education and experience in this area and find it difficult to prioritise time for this activity (de Diego-Cordero et al., 2021). Furthermore, there was very little evidence based research that explored the effects of spiritual support.

In their work, da Silva et al. (2019) demonstrated the benefits of spiritual support for those coping with breast cancer. However, nurses are not always aware of such benefits as the development of nurses’ competencies is a very recent initiative (EPICC, 2021; van Leeuwen et al., 2021), and there appears to be a lack of nursing research in this area. While the review found that nurses had a commitment to providing spiritual support and believed that patients and families found this important, much is needed to strengthen and support nurses’ roles and understandings around spiritual care provision, and to drive applied research in this field.

It is unclear from this review how spirituality is expressed from either the patient or family perspectives. It was also unclear, given the dearth of literature, what the nature of the issues were as experienced and encountered by individuals and families with regard to spirituality within healthcare in the context of a pandemic. The complexity and diverse nature of patients’ and families’ needs, clearly warrants attention. There are a range of spiritual needs (physical, emotional, cognitive, psychosocial, behavioural) and felt needs limitedly expressed by patients and families; however, this review revealed an account that was biased toward the perspectives of healthcare chaplaincy and nurses. Furthermore, the very far reaching role that healthcare chaplains (Timmins et al., 2018) and indeed nurses can play (EPICC, 2021) in providing spiritual support was under reported as the studies dealt merely with interventions such as presence, prayer and the provision of meaningful spiritual objects.

Key aspects of expressed needs within context of studies were not addressed in full such as the fear of death, lack of closure around death spiritual distress or other existential associated concerns (Drummond & Carey, 2020; Galehdar et al., 2020). However, this finding is not surprising, and a recent review that explored media coverage of spiritual support during COVID-19 (Papadopoulos et al., 2020) reflected a similar lack of specifics in relation to care provision during this time. Furthermore, these authors noted that while spiritual support was highly valued, there was “inadequate beside spiritual support” (Papadopoulos et al., 2020:104). They also highlighted gaps in staff education and training in this topic and the need for a “national spiritual support strategy for major health emergencies and disasters” (Papadopoulos et al., 2020).

However, one positive and important step in improving nurses’ understanding of spirituality and spiritual care provision is the recent initiation of the Erasmus Plus Project “From Cure to Care, Digital Education and Spiritual Assistance in Healthcare” (2021, Timmins et al., 2022). This project aims to develop educational resources for nurses to provide spiritual care. An E-Learning programme to support religious-spiritual competencies within a multicultural perspective will be developed that hopes to address’s national and international gaps in nurses’ knowledge and skills and improve their confidence in support patients’ spiritual needs.

It is hoped that this emergent body of knowledge, competencies and specific tools related to spiritual care provision begins to provide the guidance and support that urgently needed across healthcare settings internationally. Hopefully, this European initiative, along with ongoing work by EPICC (2021) in the field, will also spearhead the much needed research in the area of nursing and spirituality, which is urgently needed not only to implement and evaluate nurses’ competencies but to determine the effect of these and best practice in relation to spiritual care interventions by nurses.

Conclusion

While there is a plethora of research and publication related to COVID-19 and reports of increasing attention to nurses’ psychological and moral distress (Hossain & Clatty, 2021), there is little understanding of experiences related to patients’ or families’ expression of spirituality, spiritual needs or requirement for spiritual support within healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of nurses. This scoping review revealed very little empirical material related to this topic.

The lack of attention to spirituality and spiritual care by nurses is not surprising, because although there are national and international requirements regarding the provision of spiritual care, recent reviews have found that spiritual care is largely omitted from practice (Hvidt et al. 2020; Whelan, 2019). At the same time, healthcare chaplains working in the frontline of healthcare anecdotally report an increased and intensive demand on the services (Busfield, 2020), and the various responses and challenges for healthcare chaplaincy internationally, including adapting to the use of technology to provide pastoral care (Byrne & Nuzum, 2020; Carey et al., 2020).

COVID-19 has had far reaching consequences on the healthcare system. Considerable attention has been paid within the literature to the effect of the pandemic on healthcare staff, with less attention on the effects on patients and families. Certainly this occurrence has resulted in stress for all parties; however, this is likely magnified for patients and families who find themselves at times of health crisis or witnessing end of life. The potential contribution of COVID-19 to illness and the restrictions imposed by the distancing required, served to render what are already challenging situations, to uniquely stressful ones.

The potential requirement for spiritual care during these times was anecdotally greater than ever, yet at the same time challenges remain, and nurses remain reticent about the topic, evidenced by the clear lack of attention to this domain within the published literature. More needs to be done internationally to imbed newly developed standards for nurses (EPICC, 2021) into healthcare practice and to develop and advance nursing and research practice in the field of spiritual care, and to continue to explore and develop innovate ways to support an increase in knowledge, skills and competencies among nurses globally (Timmins et al., 2022).

Limitations

One limitation of this review is that the search terms do not potentially capture the breadth of the literature in this area globally. The time period is also restricted to the advent of COVID-19, and therefore, this provides only a particular time sensitive view of the literature.

References

Armstrong, R., Hall, B. J., Doyle, J., & Waters, E. (2011). Cochrane update. “Scoping the scope” of a cochrane review. Journal of Public Health, 33, 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

Bakar, M., Capano, E., Patterson, M., McIntyre, B., & Walsh, C. J. (2020). The role of palliative care in caring for the families of patients With COVID-19. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 37(10), 866–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1049909120931506

Bowers, B., Pollock, K., Oldman, C., & Barclay, S. (2021). End of life care during COVID-19: Opportunities and challenges for community nursing. British Journal of Community Nursing, 26(1), 44–46. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2021.26.1.44

Brady, V., Timmins, F., Caldeira, S., Naughton, M. T., McCarthy, A., & Pesut, B. (2021). Supporting diversity in person-centred care: The role of healthcare chaplains. Nursing Ethics, 28(6), 935–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0969733020981746

Busfield, L. (2020). Listening on the outside: Screaming on the inside—Reflections from an acute hospital chaplain during the first weeks of COVID-19. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 8(2), 218–222. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41807

Byrne, M. J., & Nuzum, D. (2020). Pastoral closeness in physical distancing: The use of technology in pastoral ministry during COVID-19. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 10(1), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41625

Carey, L., Swift, C., & Burton, M. (2020). COVID-19: Multinational perspectives of providing chaplaincy, pastoral, and spiritual care. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 8(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41973

Cheraghi, M. A., Manookian, A., & Nasrabadi, A. N. (2014). Human dignity in religion-embedded cross-cultural nursing. Nursing Ethics, 21(8), 916–928. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014521095

Clarke, J. (2013). Spiritual care in everyday nursing practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Clyne, B., O’Neill, S. M., Nuzum, D., O’Neill, M., Larkin, J., Ryan, M., & Smith, S. M. (2019). Patients’ spirituality perspectives at the end of life: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002016

Coppola, I., Rania, N., Parisi, R., & Lagomarsino, F. (2021). Spiritual well-being and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021Clarke.626944

Damani, A., Ghoshal, A., Rao, K., Singhai, P., Rayala, S., Rao, S., Ganpathy, K. V., Krishnadasan, N., Verginiaz, L., Vallath, N., Palat, G., Venkateshwaran, C., Jenifer, J. S., Matthews, L., Macaden, S., Muckaden, M. A., Simha, S., Salins, N., Johnson, J., Butola, S., & Bhatnagar, S. (2020). Palliative care in coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Position statement of the Indian association of palliative care. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 26(Suppl 1), S3–S7. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_207_20

da Silva, W. B., Barboza, M. T. V., Calado, R. S. F., Vasconcelos, J. L. A., & de Carvalho, M. V. G. (2019). Experience of spirituality in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Journal of Nursing UFPE on Line, 13, e241325. https://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963.2019.241325

de Diego-Cordero, R., Lopez-Gomez, L., Lucchetti, G., & Badanta, B. (2021). Spiritual care in critically ill patients during COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Outlook, 70(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2021.06.017

Dein, S., Loewenthal, K., Lewis, C. A., & Pargament, K. I. (2020). COVID-19, mental health and religion: An agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1768725

DeVries, K., Banister, E., Dening, K. H., & Ochieng, B. (2019). Advance care planning for older people: The influence of ethnicity, religiosity, spirituality and health literacy. Nursing Ethics, 26(7–8), 1946–1954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019833130

Dhollande, S., Taylor, A., Meyer, S., & Scott, M. (2021). Conducting integrative reviews: A guide for novice nursing researchers. Journal of Research in Nursing, 26(5), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1744987121997907

Drummond, D. A., & Carey, L. B. (2020). Chaplaincy and spiritual care response to COVID-19: An Australian case study—the McKellar centre. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 8(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41243

Fang, H. F., Susanti, H. D., Dlamini, L. P., Nae-Fang, M., & Min-Huey, C. (2022). Validity and reliability of the spiritual care competency scale for oncology nurses in Taiwan. BMC Palliative Care, 21, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00903-w

Finiki, A. K., & Maclean, K. (2020). Spiritual care services nurture wellbeing in a clinical setting during COVID-19: Aotearoa New Zealand. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 8(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.42129

Forlenza, O. V., & Vallada, H. (2018). Spirituality, health and well-being in the elderly. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(12), 1741–1742. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610218001874

From Cure to Care. Digital Education and Spiritual Assistance in Healthcare. (2021). l KA226, strategic partnerships for higher education: Digital education readiness, from Erasmus+ programme. Retrieved 7 Feb 2022 from http://research.unir.net/blog/project-from-cure-to-care-digital-education-and-spiritual-assistance-in-hospital-healthcare/

Galehdar, N., Toulabi, T., Kamran, A., & Heydari, H. (2020). Exploring nurses’ perception about the care needs of patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00516-9

Geppert, C. M. A., & Pies, R. W. (2020). The upside and downside of religion, spirituality, and health. Psychiatric Times, 37(7), 13–15.

Giffen, S., & Macdonald, G. (2020). Report for the association of chaplaincy in general practice on spiritual care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 8(2), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41767

Gray-Miceli, D., Bouchaud, M., Mitchell, A. B., DiDonato, S., & Siegal, J. (2020). Caught off guard by COVID-19: Now what? Geriatric Nursing, 41(6), 1020–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.10.009

Hashmi, F. K., Iqbal, Q., Haque, N., & Saleem, F. (2020). Religious cliché and stigma: A brief response to overlooked barriers in COVID-19 management. Journal of Religion and Health, 59(6), 2697–2700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01063-y

Heidari, M., Yoosefee, S., & Heidari, A. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic and the necessity of spiritual care. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 15(3), 262–263. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijps.v15i3.3823

Hossain, F., & Clatty, A. (2021). Self-care strategies in response to nurses’ moral injury during COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Ethics, 28(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020961825

Hvidt, N. C., Nielsen, K. T., Kørup, A. K., Prinds, C., Hansen, D. G., Viftrup, D. T., Assing Hvidt, E., Hammer, E. R., Falkø, E., Locher, F., Boelsbjerg, H. B., Wallin, J. A., Thomsen, K. F., Schrøder, K., Moestrup, L., Nissen, R. D., Stewart-Ferrer, S., Stripp, T. K., Steenfeldt, V. Ø., … Wæhrens, E. E. (2020). What is spiritual care? Professional perspectives on the concept of spiritual care identified through group concept mapping. BMJ Open, 10(12), e042142. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042142

Imber-Black, E. (2020). Rituals in the time of COVID-19: Imagination, responsiveness, and the human spirit. Family Process, 59(3), 912–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12581

Medical Independent, (2013). DNE Chaplaincy Wage Bill €1.6m. Retrieved from 27 Jan 2016 http://www.medicalindependent.ie/22566/dne_chaplaincy_wage_bill_1.6m

Koenig, H., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press.

La Cour, P., & Hvidt, N. C. H. (2010). Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: Secular, spiritual and religious existential orientation. Social Science and Medicine, 71(7), 1292–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.024

Labrague, L. J., McEnroe-Petitte, D. M., Achaso, R. H., Cachero, G. S., & Mohammad, M. R. A. (2016). Filipino nurses spirituality and provision of spiritual nursing care. Clinical Nursing Research, 25(6), 607–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773815590966

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Murgia, C., Notarnicola, I., Rocco, G., & Stievano, A. (2020). Spirituality in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics, 27(5), 1327–1343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020909534

Nascimento, L., Alvarenga, W. A., Caldeira, S., Mica, T. M., Oliveira, F., Santos, T. F. M., Carvalho, E. C., & Vieira, M. (2016). Spiritual care: The nurses’ experiences in the pediatric intensive care unit. Religions, 7(3), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030027

National Secular Society. (2009). Bulletin Summer, 42, 1–2. https://www.secularism.org.uk/uploads/nss-bulletin-summer-09-(2).pdf

Nissen, R. D., & Andersen, A. H. (2021). Addressing religion in secular healthcare: Existential communication and the post-secular negotiation. Religions, 13, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010034

Enhancing Nurses and Midwives' Competence in Providing Spiritual Care through Innovation, Education and Compassionate Care (EPICC), (2021). Retrieved 24 April 2021 from http://blogs.staffs.ac.uk/epicc

Nuzum, D. (2016). The human person at the heart of chaplaincy. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 6(2), 141–143. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.36911

Nuzum, D., Fitzgerald, B., Evans, M. J., & O’Donoghue, K. (2021). Maternity healthcare chaplains and perinatal post-mortem support and understanding in the United Kingdom and Ireland: An exploratory study. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(3), 1924–1936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01176-4

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetziaff, J. M., Aki, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021a). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021b). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

Papadopoulos, I., Lazzarino, R., Wright, S. E., Logan, P., & Koulouglioti, C. (2020). Spiritual support for hospitalised COVID-19 patients during March to May 2020. Research centre for transcultural studies in health. Middlesex University.

Peteet, J. R., Zaben, F. A., & Koenig, H. G. (2018). Integrating spirituality into the care of older adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610218000716

Peters, M., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18, 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Pierce, A., Hoofer, M., Marcinkowski, B., Manfredi, R. A., & Pourmand, A. (2021). Emergency department approach to spirituality care in the era of COVID-19. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 46, 765–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/2Fj.ajem.2020.09.026

Pies, R. W. (2020). Care of the Soul in the time of COVID-19. Psychiatric Times, 37(5), 16–17.

Rao, S. R., Spruijt, O., Sunder, P., Daniel, S., Chittazhathu, R. K., Nair, S., Leng, M., Sunil Kumar, M. M., Raghavan, B., Manuel, A. J., Rijju, V., Vijay, G., Prabhu, A. V., Parameswaran, U., & Venkateswaran, C. (2020). Psychosocial aspects of COVID-19 in the context of palliative care: A quick review. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 26(1), S116–S120. https://doi.org/10.4103/2FIJPC.IJPC_183_20

Rathore, P., Kumar, S., Haokip, N., Ratre, B. K., & Bhatnagar, S. (2020). CARE: A holistic approach toward patients during pandemic: Through the eyes of a palliative physician. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 26(Suppl1), S95–S98. https://doi.org/10.4103/2FIJPC.IJPC_175_20

Rentala, S., & Ng, S. M. (2021). Application of mobile call-based integrative body-mind-spirit (IBMS) intervention to deal with psychological issues of COVID-19 patients: A case study in India. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 39(4), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010121993001

Roman, N. V., Mthembu, T. G., & Hoosen, M. (2020). Spiritual care: ’A deeper immunity’—A response to Covid-19 pandemic. African Journal Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 12(1), e1–e3. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2456

Sanchetee, P., & Sanchetee, P. (2020). COVID-19 and spiritual technologies: Turn ‘Bane’ to ‘Boon.’ International School for Jain Studies Transactions, 4(3), 15–24.

Schellekens, T., Dillen, A., & Dezutter, J. (2020). Experiencing Grace: Thematic network analysis of person-level narratives. Open Theology, 6(1), 360–373. https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2020-0108

Swift, C. (2014). Hospital chaplaincy in the 21th century: The crisis of spiritual care on the NHS (2nd ed.). Ashgate.

Tata, B., Nuzum, D., Murphy, K., Karimi, L., & Cadge, W. (2021). Staff-care by chaplains during COVID-19. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: JPCC, 75(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1542305020988844

Thauvoye, E., Vanhooren, S., Vandenhoeck, A., & Dezutter, J. (2020). Spirituality among nursing home residents: A phenomenology of the experience of spirituality in late life. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 32(1), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2019.1631939

TheJournal.ie. HSE Chaplains Earn Twice As Much As Average Priest. (2013), Retrieved from 2 May 2021 http://www.thejournal.ie/hse-chaplains-earn-twice-as-much-as-average-priest-795784-Feb2013/

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Timmins, F., Connolly, M., Palmisano, S., Burgos, D., Soriano, V., Jewdokimow, M., Ganguly, S., Vázquez García-Peñuela, J. M., Lopez, A., Majda, A., Juarez, L.M., Caballero, D. C., Gusman, A., Campagna, S., Picardi, C., & Bartoletti C. (2022). Providing spiritual Care to in-hospital patients during COVID 19: A Preliminary European fact-finding study. Journal of Religion and Health.

Timmins, F., Caldeira, S., Murphy, M., Pujol, N., Sheaf, G., Weathers, E., Whelan, J., & Flanagan, B. (2018). The role of the healthcare chaplain: A literature review. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 24(3), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2017.1338048

Umucu, E., & Lee, B. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID-19 on stress and coping strategies in individuals with disabilities and chronic conditions. Rehabilitation Psychology, 65(3), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000328

van Leeuwen, R., Attard, J., Ross, L., Boughey, A., Giske, T., Kleiven, T., & McSherry, W. (2021). The development of a consensus-based spiritual care education standard for undergraduate nursing and midwifery students: An educational mixed methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(2), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14613

Weathers, E., McCarthy, G., & Coffey, A. (2016). Concept analysis of spirituality: An evolutionary approach. Nursing Forum, 51(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12128

Whelan, J. (2019). Teaching and Learning about spirituality in healthcare practice settings. In F. Timmins & S. Caldeira (Eds.), Spirituality in healthcare: Perspectives for innovative practice. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04420-6_11

Wiederhold, B. K. (2020). Turning to faith and technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 Crisis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(8), 503–504. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.29191.bkw

Wu, L. F., Tseng, H. C., & Liao, Y. C. (2016). Nurse education and willingness to provide spiritual care. Nurse Education Today, 38, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.01.001

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Connolly, M., Timmins, F. Experiences Related to Patients and Families’ Expression of Spiritual Needs or Spiritual Support Within Healthcare Settings During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. J Relig Health 61, 2141–2167 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01556-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01556-y