Abstract

Objectives

Prior theoretical scholarship makes strong assumptions about the invariance of the age-crime relationship by sex. However, scant research has evaluated this assumption. This paper asks whether the age-crime curve from age 12–30 is invariant by sex using a contemporary, nationally representative sample of youth, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 cohort (NLSY97).

Methods

To address the limitations of the existing empirical literature, a novel localized modeling approach is used that does not require a priori assumptions about the shape of the age-crime curve. With a non-parametric method—B-spline regression, the study models self-report criminal behavior and arrest by sex using age as the independent variable, and its cubic spline terms to accommodate different slopes for different phases of the curve.

Results

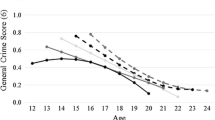

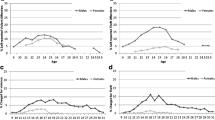

The study shows that males and females have parallel age-crime curves when modeled with self-report criminal behavior variety score but they have unique age-crime in the frequency of self-report arrest. Group-based trajectory analysis is then used to provide a deeper understanding of heterogeneity underlying the average trends. The onset patterns by sex are quite similar but the post-peak analyses using the early onset sample reveal different patterns of desistance for arrest by sex.

Conclusions

The study found evidence of relatively early and faster desistance of arrest among females but little difference exists for the variety of criminal behaviors. Implications and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some scholars report that a higher percentage of females had their first offense in adulthood, compared to male who take up a higher proportion in adolescent first offense (Bergman and Andershed 2009; Eggleston and Laub 2002). Within sex groups, however, both males and females are predominantly adolescent onsetters. Onset difference may also be driven by the use of samples of serious offenders. DeLisi (2002) used a recidivist sample of at least 30 arrests per respondent, and found the mean age of arrest onset was 18 and 20 for males and females, respectively. It is possible that chronic male offenders tend to initiate delinquent behavior earlier than chronic female offenders. Stattin et al. (1989) found that females have a peak age of onset around 21–23 for first conviction, compared to males at 15–17. In this study, the key variable is conviction. Compared to self-reported data, this may reflect that more serious female offenses were sanctioned later in the youthful time rather than early on in adolescence.

This could certainly be the result of differential treatment of women by the criminal justice system. Studies of extra-legal variation in sentencing outcomes routinely reveal large unexplained differences in the treatment of men and women in the criminal justice system (for a review, see Mitchell 2005).

NLSY97 uses a total of 147 of primary sampling units from NORC’s 1990 national sample. These units are Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas (SMSAs) or non-metropolitan counties. These SMSAs and counties were stratified by region, age, and race before selection to ensure representation. See https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/intro-to-the-sample/sample-design-screening-process for more detailed information on sampling process.

See NLSY97 Online Users’ Guide for sample description: http://www.nlsinfo.org/nlsy97/nlsdocs/nlsy97/97sample/introsample.html, http://www.nlsinfo.org/nlsy97/nlsdocs/nlsy97/maintoc.html.

Respondents who were incarcerated during the time of interview were also interviewed either by phone or in person. These respondents do not exceed 1.5 % of the sample based on the details of the reason for non-interview item (Question name: RNI). This item specifies the number of respondents interviewed during incarceration beginning in Round 10, with respondents’ age ranging from 21 to 27. Thus it is reasonable to assume that the prevalence of incarceration is also similar to this rate before Round 10, which is not considered an issue for current analysis.

See “Appendix 1” for an attrition analysis.

Imputation is done on these event history variables on arrest in the dataset for missing values. The NLSY97 documentation from NORC is forthcoming.

Not all arrests are followed with detailed questions in each survey round.

Refer to de Boor (2001: 114) for detailed explanation of this method.

The three steps are: choose the initial optimal number of internal knots; the stepwise knot deletion, and the stepwise knot addition in S-PLUS program. The latter two steps involve comparison of change in Akaike information criterion (AIC) when a knot is removed (or added).

One way to produce interpretable confidence intervals for nonparametric estimates is by bootstrapping (Wang and Wahba 1995). Bootstrapping is a resampling technique that is used to obtain inferential information on the distribution of an estimator (Hardle and Bowman 1988). Thus, bootstrapping standard errors are obtained here for the purpose of estimating statistical significance when comparing the curves by sex.

Stata Program does not allow weight in bootstrapping command due to varying sample composition from bootstrapping process.

The average values of the “weighting ratios” range from 0.92 to 1.12.

The desistance analysis uses similar spline regression specifications as that of the general analysis. Difference lies only in the sample size, and the knot points for the age variable (See Table 3 for knots of general and desistance analysis).

Stata Software user-written package (“traj”) for trajectory analysis is used. It is written by Bobby L. Jones, based on his work with Daniel Nagin (http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/bjones, see Jones et al. 2001 for methodology discussion).

The 30-years old respondents are fewer than 15, and are thus dropped from descriptive analysis. However, they are included in the spline regression.

Confidence intervals of all estimated curves are calculated and adjusted with design effect. They are available upon request. It is not shown on the graphs due to indiscernible difference from the estimated curves in current scale.

The B-spline method is argued to constrain the upticks often seen with cubic polynomial functions. Nevertheless, there are visible upticks in current Fig. 2a, b. It is important to bear in mind that the number of observations at extremities of the curve is much smaller compared to the main body of the curve due to the cohort structure of the NLSY97. This fact is reflected in the much wider bounds at the ends of the curves.

These respondents are either non-offenders or offending once only very early in the survey history.

Chow tests are also performed for the subsamples. All reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients of the combined model are the same as that of the separate models.

Additional analyses on separate items of the self-report criminal behavior (vandalism, attacking someone, and a pooled three-item property offense) were conducted to compare the sex difference in the age-crime curves of different types of offenses, with an attempt to examine underlying heterogeneity. All three sets of curves show a similar pattern with males reporting a higher level for each variable and the male and female curves are parallel.

Respondents’ arrest charges were analyzed to examine whether there is a sex difference by arrest charge type. The charges reported in NLSY97 include eight categories: robbery, assault, theft, burglary, vandalism, other property offense, drug trafficking, and drug possession. All eight curve-comparisons show an earlier peak and a lower level for females than males to a varying degree. Thus, the conclusion of current study remains consistent regardless of the types of arrests.

References

Andersson F, Levander S, Svensson R, Levander MT (2012) Sex differences in offending trajectories in a Swedish cohort. Crim Behav Ment Health 22(2):108–121

Apel R, Kaukinen C (2008) On the relationship between family structure and antisocial behavior: parental cohabitation and blended households. Criminology 46(1):35–70

Apel R, Sweeten G (2010) Propensity score matching in criminology and criminal justice. In: Weisburd D, Piquero AR (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology, 1st edn. Springer, New York

Apel R, Paternoster R, Bushway SD, Brame R (2006) A job isn’t just a job: the differential impact of formal versus informal work on adolescent problem behavior. Crime Delinq 52(2):333–369

Apel RJ, Bushway SD, Brame R, Haviland A, Nagin DS, Paternoster R (2007) Unpacking the relationship between adolescent employment and antisocial behavior: a matched samples comparison. Criminology 45(1):67–97

Apel R, Bushway SD, Paternoster R, Brame R, Sweeten G (2008) Using state child labor laws to identity the causal effect of youth employment on deviant behavior and academic achievement. J Quant Criminol 24:337–362

Beck AJ, Shipley BE (1989) Recidivism of prisoners released in, 1983. U.S. Department of Justice: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

Bergman LR, Andershed A (2009) Predictors and outcomes of persistent or age-limited registered criminal behavior: a 30-year longitudinal study of a Swedish urban population. Aggress Behav 35:164–178

Bersani BE (2012) An examination of first and second generation immigrant offending trajectories. Justice Q iFirst Article, 1–29

Bishop DM, Frazier CE (1992) Gender bias in juvenile justice processing: implications of the JJDP Act. J Crim Law Criminol 82(4):1162–1186

Block CR, Blokland AAJ, van der Werff C, van Os R, Nieuwbeerta P (2010) Long-term patterns of offending in women. Fem Criminol 5(1):73–107

Blokland AJ, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) The effects of life circumstances on longitudinal trajectories of offending. Criminology 43(4):1203–1240

Blokland AJ, Nagin DS, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) Life span offending trajectories of a dutch conviction cohort. Criminology 43(4):919–954

Brame R, Piquero AR (2003) Selective attrition and the age-crime curve. J Quant Criminol 19(2):107–127

Britt C (1992) Constancy and change in the US. Age distribution of crime: a test of “Invariant hypothesis”. J Quant Criminol 8(2):175–187

Britt C (1994) Model specification and interpretation: a reply to Greenberg. J Quant Criminol 10(4):375–379

Bushway SD, Sweeten G, Nieuwbeerta P (2009) Measuring long term individual trajectories of offending using multiple methods. J Quant Criminol 25:259–286

Chow GC (1960) Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica 28(3):591–605

de Boor C (2001) A practical guide to splines. Springer, New York

DeFleur LB (1975) Biasing influences on drug arrest records: implications for deviance research. Am Sociol Rev 40(1):88–103

DeLisi M (2002) Not just a boy’s club: an empirical assessment of female career criminals. Women Crim Justice 13(4):27–45

D’Unger A, Land K, McCall P (2002) Sex differences in age patterns of delinquent/criminal careers: result from poisson latent class analyses of the Philadelphia cohort study. J Quant Criminol 18(4):349–375

Edin K, Kefalas M (2005) Promises I can keep: why poor women put motherhood before marriage. University of California Press, Berkeley

Eggleston EP, Laub JH (2002) The onset of adult offending: a neglected dimension of criminal career. J Crim Justice 30(6):603–622

Eilers PHC, Marx BD (1996) Flexible smoothing with b-splines and penalties. Statist Sci 11(2):89–102

Farrington D (1986) Age and crime. Crim Justice 7:189–250

Farrington DP, West DJ (1995) Effects of marriage, separation, and children on offending by adult males. Curr Perspect Aging Life Cycle 4:249–281

Farrington DP, Loeber R, Elliott DS, Hawkins JD, Kandel DB, Klein MW, McCord J, Rowe DC, Tremblay RE (1990) Advancing knowledge about the onset of delinquency and crime. Adv Clin Child Psychol 13:283–342

Fry LJ (1985) Drug abuse and crime a Swedish birth cohort. Br J Criminol 25(1):46–59

Gendreau P, Little T, Goggin C (1996) A meta-analysis of the predictors of adult offender recidivism: what works! Criminology 34(4):575–607

Gibbons JD (1993) Nonparametric statistics: an introduction. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park

Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA, Rudolph JL (2002) Gender, crime, and desistance: toward a theory of cognitive transformation. Am J Sociol 107(4):990–1064

Gove WR (1985) The effect of age and gender on deviant behavior: a biopsychosocial perspective. In: Rossi A (ed) Gender and the life course. Aldine Publishing Company, Hawthorne

Goethals J, Maes E, Klinckhamers P (1997) Sex/gender-based decision-making in the criminal justice system as a possible (additional) explanation for the underrepresentation of women in official criminal statistics—a review of international literature. Int J of Comp and Appl Crim Just 21(2):207–240

Graham J, Bowling B (1995) Young people and crime. Home Office, London

Greenberg DF (1977) Delinquency and the age structure of society. Crime Law Soc Change 1(2):189–223

Greenberg DF (1994) The historical variability of the age-crime relationship. J Quant Criminol 10(4):361–373

Hagan J, Simpson J, Gillis AR (1987) Class in the household: a power-control theory of gender and delinquency. Am J Sociol 92(4):788–816

Hardle W, Bowman AW (1988) Bootstrapping in nonparametric regression: local adaptive smoothing and confidence bands. J Am Stat Assoc 83(401):102–110

He X, Ng P (1999) COBS: qualitatively constrained smoothing via linear programming. Comput Stat 14(3):315–338

Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG (1981) Measuring delinquency. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Hirschi T, Gottfredson M (1983) Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 89(3):552–584

Jennings WG, Maldonado-Molina MM, Piquero AR, Odgers CL, Bird H, Canino G (2010) Sex differences in trajectories of offending among Puerto Rican youth. Crime Delinq 56(3):327–357

Johnson WT, Petersen RE, Wells LE (1977) Arrest probabilities for marijuana users as indicators of selective law enforcement. Am J Sociol 83(3):681–699

Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K (2001) A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res 29(3):374–393

Keele LJ (2008) Semi parametric regression for the social sciences. Wiley, West Sussex

Kerr DR, Capaldi DM, Owen LD, Wiesner M, Pears KC (2011) Changs in at-risk American men’s crime and substance use trajectories following fatherhood. J Marriage Fam 73:1101–1116

Kirk DS (2006) Examining the divergence across self-report and official data sources on inferences about the adolescent life-course of crime. J Quant Criminol 22(2):107–129

Kreager DA, Matsueda RL, Erosheva EA (2010) Motherhood and criminal desistance in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Criminology 48(1):221–258

Langan PA, Levin DJ (2002) Recidivism of prisoners released in, 1994. U.S. Department of Justice: Bureau of Justice Statitics, Washington DC

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2001) Understanding desistance from crime. Crime Justice 28:1–69

Mazerolle P, Brame R, Paternoster R, Piquero A, Dean C (2000) Onset age, persistence, and offending versatility: comparisons across gender. Criminology 38(4):1143–1172

Mitchell O (2005) A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: explaining the inconsistencies. J Quant Criminol 21(4):439–466

Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100(4):674–701

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA (2001) Sex differences in antisocial behaviour: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Monahan TP (1970) Police dispositions of juvenile offenders: the problems of measurement and a study of Philadelphia data. Phylon (1960) 31(2):129–141

Moore W, Pedlow S, Krishnamurty P, Wolter K (2000) National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97) Technical Sampling Report

Nagin DS (2005) Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nagin DS, Land K (1993) Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity. Criminology 31(3):327–362

Nieuwbeerta P, Blokland AAJ, Piquero AR, Sweeten G (2011) A life-course analysis of offense specialization across age: introducing a new method for studying individual specialization over the life course. Crime Delinq 57(1):3–28

Opsomer JD, Breidt FJ, Claeskens G, Jauermann G, Ranalli MG (2008) Nonparametric small area estimation using penalized spline regression. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 70(1):265–286

Osborne MR, Presnell B, Turlach BA (1998) Knot selection for regression splines via the LASSO. Comput Sci Stat 30:44–49

Paternoster R, Bushway S (2009) Desistance and the “feared self”: toward an identity theory of criminal desistance. J Crim Law Criminol 99(4):1103–1156

Piquero AR, Chung H (2001) On the relationships between gender, early onset, and the seriousness of offending. J Crim Justice 29(3):189–206

Piquero A, Brame R, Moffitt T (2005) Extending the study of continuity and change: gender differences in the linkage between adolescent and adult offending. J Quant Criminol 21(2):219–243

Rowe DC, Osgood DW, Nicewander WA (1990) A latent trait approach to unifying criminal careers. Criminology 28(2):237–270

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (2005) A life-course view of the development of crime. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 602(12):12–45

Shannon SKS, Adrams LS (2007) Juvenile offenders as fathers: perceptions of fatherhood, crime, and becoming an adult. Fam Soc J Contemp Soc Serv 88(2):183–191

Skardhamar T, Lyngstad TH (2009) Family formation, fatherhood and crime: an invitation to a broader perspective on crime and family transitions. Discussion Papers No. 579, Statistics Norway, Research Department

Stattin H, Magnusson D, Reichel H (1989) Criminal activity at different ages: a study based on a Swedish longitudinal research population. Br J Criminol 29(4):368–385

Steffensmeier D, Allan E (1996) Gender and crime: toward a gendered theory of female offending. Ann Rev Sociol 22:459–487

Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ (2004) Sex differences in the likelihood of arrest. J Crim Justice 32:443–454

Sweeten GA, Apel RJ (2007) Incapacitation: revisiting an old question with a new method and new data. J Quant Criminol 23(4):303–326

Sweeten G, Bushway SD, Paternoster R (2009) Does dropping out of school mean dropping into delinquency? Criminology 47(1):47–91

Sweeten G, Piquero AR, Steinberg L (2013) Age and the explanation of crime, revisited. J Youth Adolesc 42:921–938

Telesca D, Erosheva EA, Kreager DA, Matsueda RL (2012) Modeling criminal careers as departures from a unimodal population age-crime curve: the case of marijuana use. J Am Stat Assoc 107(500):1427–1440

Tittle CR, Grasmick HG (1998) Criminal behavior and age: a test of three provocative hypotheses. J Crim Law Criminol 88(1):309–342

Uggen C (2000) Work as a turning point in life course of criminals: a duration model of age, employment and recidivism. Am Sociol Rev 65(4):529–546

Uggen C, Kruttschnitt C (1998) Crime in the breaking: gender differences in desistance. Law Soc Rev 32:339–366

Wang Y, Wahba G (1995) Bootstrap confidence intervals for smoothing splines and their comparison to Bayesian confidence intervals. J Stat Comput Simul 51(2–4):263–279

Wiesner M, Capaldi DM, Kim HK (2007) Arrest trajectories across a 17-year span for young men: relation to dual taxonomies and self-reported offense trajectories. Criminology 45(4):835–863

Zara G, Farrington DP (2009) Childhood and adolescent predictors of late onset criminal careers. J Youth Adolesc 28:287–300

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Shawn Bushway, Justin Pickett and the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript for their advice and helpful comments on this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Attrition

Attrition started to occur since Round 2. Thus, attrition analysis is used to examine whether the respondents who drop out from the survey at any given round, regarded as “the attritted group,” would indicate non-randomness among major dependent variables. Table 7 below provides a yearly description of the number of respondents and attrition rate, which is shown to peak around Round 9 (for 2005). The concern is that the attritted group may differ significantly from the retained group in items of interest, therefore undermining the representativeness envisioned during the initial sampling.

The only round that has complete data on all measure—Round 1—is used for statistical comparison on surveyed and attrited respondents of subsequent rounds. For example, we know who were interviewed and who attritted at Round 5. So dividing the entire sample into these two groups, the Round 1 data on the interested items are compared and tested. It is shown that respondents who attrited at Round 5 are significantly more likely to be females and less likely to be involved in substance use. No significance on the t tests of other variables is present. Other rounds with these two changing groups of respondents can be interpreted similarly (Table 8).

Appendix 2: Period Effect

Period effect refers to the influence specific to a particular historical time period (Farrington, 1986, p203). Because of the unavailability of individual official record for the respondents in the NLSY97, I use the official arrest data obtained from the Bureau of Justice Statistics Data Analysis Tools (Snyder, 2011), then compare the trends of arrest rate by gender from 1999 to 2009 corresponding to the study period of 1997–2009. Figure 6 shows little fluctuation in arrest rates by year from the official data for both males and females (Age 0–17). This official UCR data suggests that the study sample is collected during a relatively stable time period in a national backdrop that would not confound the age-crime curve from self-reported data NLSY97. Therefore, no alarming period effect should be considered.

These official data source also largely substantiate the self-reported arrest rate shown in Fig. 4b on frequency of arrest. The official estimates here shown in Fig. 6 for male are relatively lower than the NLSY97 estimates for the younger age group and higher for the older age group. For males, the official average arrest rate is 0.2 for 18–29 years old youth and .16 for self-report version. For females, the official rate on average is about 0.05 compared to the average rate of .04 for self-report. The officially defined “juveniles” who are the under-18 youth has an average of .05 for male and .02 for female. The corresponding group from NLSY97 reports an average of 0.1 for male and .05 for female.

Appendix 3: Cohort Effect

Cohort effect refers to the influence for a specific cohort due to the year they were born (Farrington, 1986, p203). To examine this, I break down the sample by five cohorts based on the year they were born (1985–1989). Figure 7 indicates two out of the five cohorts on the arrest rates by cohort and age. As it is clearly shown, for both male and female subsamples, the youngest and oldest cohorts overlap each other relatively well, implying little evidence for cohort-related bias. Similar conclusion is suggested for prevalence of marijuana use (figure not shown).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S. Is the Shape of the Age-Crime Curve Invariant by Sex? Evidence from a National Sample with Flexible Non-parametric Modeling. J Quant Criminol 31, 93–123 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9225-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9225-6