Abstract

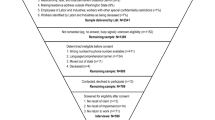

Introduction To investigate differences in modified-return-to work (MRTW) within the first 30 days of a work-related, short-term disability injury by immigration characteristics. This question was part of a program of research investigating differences in work and health experiences among immigrant workers and explanations for longer work disability durations. Methods Workers’ compensation claims, immigration records and medical registry data were linked to identify a sample of workers in British Columbia, Canada with a short-term disability claim for a work-related back strain, concussion, limb fracture or connective tissue injury occurring between 2009 and 2015. Multivariable logistic regressions, stratified by injury type, investigated the odds of MRTW, defined as at least one day within the first 30 days on claim, associated with immigration characteristics, defined as a Canadian-born worker versus a worker who immigrated via the economic, family member or refugee/other humanitarian classification. Results Immigrant workers who arrived to Canada as a family member or as a refugee/other immigrant had a reduced odds of MRTW within the first 30 days of work disability for a back strain, concussion and limb fracture, compared to Canadian-born workers. Differences in MRTW were not observed for immigrant workers who arrived to Canada via the economic classification, or for connective tissue injuries. Conclusion The persistent and consistent finding of reduced MRTW for the same injury for different immigration classifications highlights contexts (work, health, social, language) that disadvantage some immigrants upon arrival to Canada and that persist over time even after entry into the workforce, including barriers to MRTW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data was obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The workers’ compensation, immigration data, and Ministry of Health were made available to the researchers by Population Data BC (www.popdata.bc.ca) with permission from the data stewards. The data was made available for the sole purposes of achieving the research objectives and is not available for sharing.

Notes

Workers could have had MRTW beyond the 30-day window but the purpose of this analyses was focused on MRTW within the critical 30-day window of acute work disability.

References

Krause N, Dasinger LK, Neuhauser F. Modified work and return to work: A review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 1998;8(2):113–139.

Franche R-L, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: A systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):607–631.

Foster J, Barnetson B, editors. Disability management and return to work. In: Health and Safety in Canadian Workplaces. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press; 2016.

Blinder V, Eberle C, Patil S, Gany FM, Bradley CJ. Women with breast cancer who work for accommodating employers more likely to retain jobs after treatment. Health Aff. 2017;36(2):274–281.

Hill MJ, Maestas N, Mullen KJ. Employer accommodation and labor supply of disabled workers. Labour Econ. 2016;41:291–303.

Høgelund J, Holm A. Worker adaptation and workplace accommodations after the onset of an illness. IZA J Labor Policy. 2014;3(1):17.

Burkhauser RV, Butler JS, Kim YW. The importance of employer accommodation on the job duration of workers with disabilities: a hazard model approach. Labour Econ. 1995;2(2):109–130.

Krause N, Lund T. Returning to work after occupational injury. In J. Barling & M.R. Frone, editors, The Psychology of Workplace Safety (pp. 265–295). American Psychology Association. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1037/10662-013.

Gensby U, Lund T, Kowalski K, Saidj M, Jorgensen AK, Filges T, et al. Workplace disability management programs promoting return to work: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2012; 8(1).

Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, Clay F, Gensby U, Jennings PA, et al. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in return-to-work for musculoskeletal, pain-related ad mental health conditions: An update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):1–15.

Franche R-L, Severin CN, Hogg-Johnson S. Côté P, Vidmar M, Lee H. The impact of early workplace-based return-to-work strategies on work absence duration: a 6-month longitudinal study following an occupational musculoskeletal injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(9):960–974.

McLaren CF. Reville RT. Seabury SA. How effective are employer return to work programs? Int Rev Law Econ. 2017;52:58–73.

Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, Clay F, Gensby U, Jennings PA, Hogg-Johnson S, Kristman V, Laberge M, McKenzie D, Newnam S, Palagyi A, Ruseckaite R, Sheppard DM, Shourie S, Steenstra I, Van Eerd D, Amick BC III. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in return-to-work for musculoskeletal, pain-related and mental health conditions: An update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):1–15.

The Government of British Columbia. Human Rights Code. RSBC 1996. Chapter 210. Queen’s Printer: Victoria, British Columbia. Available: https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/00_96210_01.

The Government of British Columbia Workers Compensation Act – BC Laws [RSBC 1979]. Chap. 437. Queen’s Printer: Victoria, British Columbia. Available: https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/92consol16/92consol16/79437.

Fuller S, Vosko LF. Temporary employment and social inequality in Canada: Exploring intersections of gender, race and migration. Soc Indic Res. 2008;88(1):31–50.

Smith P, Chen C, Mustard C. Differential risk of employment in more physically demanding jobs among a recent cohort of immigrants to Canada. Inj Prev. 2009;15(4):252–258.

Shuey KM, Jovic E. Disability accommodation in nonstandard and precarious employment arrangements. Work Occup. 2013;40(2):174–205.

MacEachen E, Senthanar S, Lippel K. Compensation for precarious workers in Ontario: Resistance from employers and limited voice for victims of work-related injuries. PISTES. 2021; 23(1).

Caidi N, Allard D. Social inclusion of newcomers to Canada: An information problem? Libr Inf Sci Res. 2005;27(3):302–324.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Lifshen M, Smith P, Jaffri GJ, Neilson C, et al. Delicate dances: Immigrants workers’ experiences of injury reporting and claim filing. Ethn Health. 2012;17(3):267–290.

Premji S. Barriers to return-to-work for linguistic minorities in Ontario: An analysis of narratives from appeal decisions. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25:357–367.

Gravel S, Vissandjee B, Lippel K, Brodeur J-M, Patry L, Champagne F. Ethics and the compensation of immigrant workers for work-related injuries and illnesses. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(5):707–714.

Côté D. Intercultural communication in health care: challenges and solutions in work rehabilitation practices and training: a comprehensive review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(2):153–163.

Smith P, Chen C, Mustard C. Differential risk of employment in more physically demanding jobs among a recent cohort of immigrants to Canada. Inj Prev. 2009;15(4):252–258.

Yanar B, Kosny A, Smith PM Occupational health and safety vulnerability of recent immigrants and refugees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018; 15(9): 2004.

Kosny A, Yanar B, Begum M, Al-khool D, Premji S, Lay MA, et al. Safe employment integration of recent immigrants and refugees. J Int Migr Integr. 2020;21(3):807–827.

Krause N, Frank JW, Dasinger LK, Sullivan TJ, Sinclair SJ. Determinants of duration of disability and return-to-work after work-related injury and illness: challenges for future research. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(4):464–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.1116.

Saffari N, Senthanar S, Koehoorn M, McGrail K, McLeod CB. Immigrant status, gender and work disability duration: Findings from linked workers’ compensation and immigration data in British Columbia, Can BMJ Open,2021;11(12): https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050829.

Senthanar S, Koehoorn M, Tamburic L, Premji S, Bültmann U, McLeod CB. Differences in work disability duration for immigrant and Canadian-born workers in British Columbia, Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health: Special Issue Work Health Equity. 2021;18(22):11794. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211794.

Maas ET, Koehoorn M, McLeod CB. Does gradually returning to work improve time to sustainable work after a work-acquired musculoskeletal disorder in British Columbia, Canada? A matched cohort effectiveness study. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78(10):715–723.

de Castro AB, Fujishiro K, Sweitzer E, Oliva J. How immigrant workers experience workplace problems: A qualitative study. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2006;61(6):249–258.

Daley D, Payne LP, Galper J, Cheung A, Deal L, Clinical guidance to optimize work participation after injury or illness: The role of physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(8):CPG1–CPG102. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2021.0303

Burton A, Bartys S, Wright I, Main CJ. Obstacles to Recovery from Musculoskeletal Disorders in Industry. London: HSE Books; 2005.

WorkSafeBC [creator]. WorkSafeBC claims, injured Worker, and return to work files. Population Data BC [publisher]. Linked Data Set. WorkSafeBC. 2018. Available: http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]. Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH. 2019. Available: http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

Immigration R, and Citizenship Canada [creator]. Permanent Resident database. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. IRCC. 2020. Available: http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

Population Data BC. About PopData. 2021. Available: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/about.

Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada. Detailed key statistical measures (KSM) report. 2015. Available: http://awcbc.org/?page_id=9759.

McLeod CB, MacPherson R, Quirke W, Fan J, Amick IIIBC, Mustard CA, et al. Work disability duration: A comparative analysis of three Canadian provinces. Final report to the Workers’ Compensation Board of Manitoba; July 2017.

Krieger N. Genders, sexes, and health: What are the connections–and why does it matter? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(4):652–657.

Smith PM, Mustard C. The unequal distribution of occupational health and safety risks among immigrants to Canada compared to Canadian-born labour market participants: 1993–2005. Saf Sci. 2010;48(10):1296–1303.

Macpherson RA, Lane TJ, Collie A, McLeod CB. Exploring differences in work disability by size of firm in Canada and Australia. J Occup Rehabil. 2022;32:190–202.

Anderson LP, Kines P, Hasle P. Owner attitudes and self reported behavior towards modified work after occupational injury absence in small enterprises: A qualitative study. 2007;17:107–121.

Clark DE, Ahmad S. Estimating injury severity using the Barell matrix. Inj Prev. 2006;12:111–116.

LaRochelle-Côté S, Hango DW Overqualification, skills and job satisfaction. Insights on Canadian Society Catalogue. Statistics Canada: 75-006-X. 2016.

Premji S, Begum M, Medley A, MacEachen E, Côté D, Saunders R. Return-to-work in a language barrier context: Comparing Quebec’s and Ontario’s workers’ compensation policies and practices. PISTES. 2021. https://doi.org/10.4000/pistes.7144.

Premji S, Messing K, Lippel K. Broken English, broken bones? Mechanisms linking language proficiency and occupational health in a Montreal garment factory. Int J Health Serv. 2008;38(1):1–19.

Tucker S, Turner N. Waiting for safety: responses by young Canadian workers to unsafe work. J Saf Res. 2013;45:103–110.

Kazi MR, Ferdous M, Rumana N, Vaska M, Turin TC. Injury among the immigrant population in Canada: exploring the research landscape through a systematic scoping review. Int Health. 2019;11:203–214.

Nazari M. A community-based pilot study exploring work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD) perception among recently relocated Syrian refugees in Canada [dissertation]. Waterloo (CA): University of Waterloo; 2020.

Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Christine Lin C-W, Chenot J-F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated review. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(11):2791–2803.

Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, Chong N, Azimaee M, Iron K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3.

Billias N, MacEachen E, Sherifali S. “I grabbed my stuff and walked out”: Precarious workers’ responses and next steps when faced with procedural unfairness during work injury and claims processes. J Occup Rehabil. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10058-3

Funding

This research was funded in part by a Project Grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (#378435) that provided operating costs associated with the research activities of data access and analyses. MK was funded in part by a Chair in Gender, Work and Health from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research that provided investigator salary support. CB was funded in part by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research that provided investigator salary support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK, SP, UB and CBM conceived the research question and study design. SS and LT lead the data analysis. SS drafted the manuscript, with input and revisions from all study authors. All authors have read and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at The University of British Columbia (H17-02078).

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Disclaimer

All inferences, opinions and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Stewards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Senthanar, S., Koehoorn, M., Tamburic, L. et al. Differences in Modified-Return-to-Work by Immigration Characteristics Among a Cohort of Workers in British Columbia, Canada. J Occup Rehabil 33, 341–351 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10077-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10077-0