Abstract

Individuals automatically mimic a wide range of different behaviors, and such mimicking behavior has several social benefits. One of the landmark findings in the literature is that being mimicked increases liking for the mimicker. Research in cognitive neuroscience demonstrated that mentally simulating motor actions is neurophysiologically similar to engaging in these actions. Such research would predict that merely imagining being mimicked produces the same results as actually experiencing mimicry. To test this prediction, we conducted two experiments. In Experiment 1, being mimicked increased liking for the mimicker only when mimicry was directly experienced, but not when it was merely imagined. Experiment 2 replicated this finding within a high-powered online sample: merely imagining being mimicked does not produce the same effects as being actually mimicked. Theoretical and practical implications of these experiments are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Imagining is Not Observing

The Role of Simulation Processes Within the Mimicry-Liking Expressway

Individuals have the propensity to automatically imitate a wide range of different behaviors (for definitions of different forms of imitation, see Genschow et al., 2017), facial expressions (Dimberg, 1982), emotions (Hess & Fischer, 2016), postures (LaFrance, 1982), gestures (Cracco et al., 2018), or simple movements (Genschow & Florack, 2014; Genschow & Schindler, 2016; Genschow et al., 2013). Early work indicates that such imitative behavior helps infants and toddlers to learn new skills (e.g., Bandura, 1986). Other research suggests that mimicry is an important tool in psychotherapy as it fosters rapport (Charny, 1966) and a deeper understanding between psychotherapists and patients (Charny, 1966; Maurer & Tindall, 1983; Scheflen, 1964). Thus, unsurprisingly, mimicry between patients and therapists is associated with a positive psychotherapeutic outcome (Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2011, 2014).

Other work indicates that mimicry fulfills an important social function because it forms stronger bonds between humans (e.g., Duffy & Chartrand, 2015; Wang & Hamilton, 2012). For example, research demonstrated that mimickees (i.e., persons who are being mimicked) behave towards mimickers (i.e., persons who mimic) in a more prosocial (Kulesza, Dolinski, et al., 2014; Kulesza, Szypowska, et al., 2014; van Baaren et al., 2003, 2004) and trustworthy manner (Swaab et al., 2011). Certainly, one of the landmark findings in the mimicry literature is that being mimicked increases liking for the mimickers (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Kulesza et al., 2015; LaFrance & Ickes, 1981; Lakin et al., 2003; Stel & Vonk, 2010).

Mimicry is typically explained by so-called perception-behavior theories (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Greenwald, 1970; Prinz, 1997). These theories assume that individuals imitate each other because perceiving an action evokes the same mental representation as engaging in this action. In the last decades, this view has been supported by numerous neuropsychological experiments, including fMRI studies (e.g., Gazzola & Keysers, 2009; Keysers & Gazzola, 2010), motor TMS studies (e.g., Catmur et al., 2007; Fadiga et al., 1995), and single-cell recordings in both monkeys (di Pellegrino et al., 1992) and humans (Mukamel et al., 2010).

In line with this view, theories on grounded or embodied cognition postulate that bodily experiences and mental representations are intricately linked (e.g., Barsalou, 1999, 2008; Semin & Smith, 2008). Research in support of such an account has shown that sensorimotor inductions and simulations can affect attitudes (e.g., Topolinski & Boecker, 2016), memory (e.g., Topolinski, 2012), and other important social–cognitive outcomes (for a review, see Meier et al., 2012).

More specific support for the idea that mimicry is strongly based on a simulation process comes from research on anticipated action (Genschow & Brass, 2015; Genschow & Groß-Bölting, 2021; Genschow, Bardi, et al., 2018)—a phenomenon closely linked to mimicry (Genschow et al., 2018). This line of research shows that anticipating someone else’s action leads individuals to engage in the anticipated action even if the observed person does not engage in the action. For example, merely anticipating that another person will scratch her nose is sufficient to trigger nose scratching actions in the observer. An explanation for this effect is that individuals mentally simulate other people’s future actions, which, in turn, facilitates engagement in the anticipated action. In other words, imagining another person’s action is sufficient to produce the imagined action.

Going one step further, research on mental simulation suggests that merely imagining one’s own actions leads to similar behavioral outcomes as actually executing this action. For instance, Pascual-Leone et al. (1995) asked novices to engage in a specific piano exercise. While a third of participants performed the exercise for five days, another third merely imagined engaging in the exercise for 5 days, and yet another third of participants did not engage in the exercise at all. The results indicate that participants who actually played the piano outperformed the others in playing the piano. Strikingly, however, after two hours of actual piano playing, the group who merely imagined playing the piano was on the same level as the participants who physically practiced playing the piano. Participants who did not engage in the exercise the days before were not able to reach this level after two hours of training. These results suggest that mentally simulating an action is sufficient to affect actual behavior. On the other hand, research on imagining not actions but a state (Oettingen & Wadden, 1991) has shown that merely imagining a desired state (i.e., an obese person imagines “I am thin”) did not lead to a desired state (being thin). The key factor was imagining not only a state, but also actions (“I am making a huge effort at the gym”, “I do not eat cookies”). Only then was the expected outcome achieved.

Present Research

Since research on mental simulation of motor actions suggests that imagining an action is very closely linked to actually executing the action, the question arises as to what extent imagining being mimicked by another person would increase liking for this person in the same way as actually being mimicked by this person. To investigate this question, we conducted two experiments. Experiment 1 was designed as a pilot study to test the research question in a natural setting. Experiment 2 was designed to put the main result obtained in Experiment 1 to a critical test by assessing a higher-powered sample, manipulating mimicry in a more controlled way, and measuring liking in a more reliable manner.

The stimulus material and the data of our experiments are openly accessible at the Open Science Framework (OSF: https://bit.ly/3tTpzFf).

Experiment 1

Method

Participants and Design

Sixty call center operators (33 women, 27 men) with an age ranging from 19 to 40 (Mage = 27.6, SD = 5.02) participated in the experiment as part of business training. As some researchers (Arnold & Winkielman, 2020; Seibt et al., 2015) mentioned gender differences in mimicry (for a critical reflection on these findings, see Genschow, Klomfar, et al., 2018), we took great care in equally assigning male and female participants to the experimental groups. Statistical analysis demonstrates that the gender distribution between the experimental conditions was not unequal: χ2(2, N = 60) = 2.83, p = 0.243, V = 0.22. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three between-subject conditions: visible mimicry, imagined mimicry, no-mimicry. Due to the pilot nature of the experiment, the number of participants per experimental condition was twenty. No participants were removed from the analysis.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted in a natural setting as part of business training for call center operators working for a company selling decoders for digital television. We chose this setting for the first experiment because it allowed us to investigate our predictions in a natural situation. Each operator participated individually in the experiment. The experiment lasted approximately 15 min. Each operator interacted with a female confederate (in her thirties) who was blind to the hypothesis and was introduced as a coach. The ostensible goal of the training was to introduce participants to a new procedure in dealing with customers who did not return IT equipment in time.

At the beginning of the experiment, the mimicry manipulation took place. That is, participants took part in an ostensibly one-minute relaxation procedure to boost concentration during the training session. To mask the actual purpose of the study, the confederate informed participants that the relaxation procedure is a well-known method that had recently been communicated in a scientific TV program.

In standard experiments that measure the amount of mimicking behavior (e.g., Chartrand & Bargh, 1999), a confederate engages in a target action (e.g., touching the head) typically once every 20 to 30 s. The interactions are videotaped to measure participants' mimicking behavior, and coders count how often participants engaged in the same actions as the confederate. Based on the setup of such a mimicry experiment, the time delay between observed and mimicked actions lies between a few milliseconds and 30 s. In contrast, in many experiments assessing the consequences of being mimicked, confederates mirror the participants' body language, postures, and mannerisms (e.g., Chartrand & Bargh, 1999). Unfortunately, such a procedure confounds mimicry with synchrony because participants and confederates engage in the same behaviors more or less at the same time. To clearly separate synchrony from mimicry, we applied a procedure that builds on experiments assessing the amount of mimicry.

In all conditions, the coach/confederate and the participants sat opposite each other in a natural position. The confederate explained that the participants had to engage in two different relaxation exercises for 30 s each. The first exercises consisted of 30 s of massaging one’s temple and forehead with both hands. The second exercise involved 30 s of inhalations and exhalations while raising one’s right hand up and down. Participants first received verbal instructions for each exercise, and the confederate/coach controlled participants’ engagement in the exercises. Depending on the experimental condition, the confederate/coach responded to each exercise in a different manner. It is important to note that participants did not expect the confederate to engage in mimicry behavior in any of the experimental conditions. In the visible mimicry condition, participants saw after each exercise the confederate/coach engaging in the very same exercise for 30 s. In the imagined mimicry condition, participants could also see the confederate. However, after participants engaged in an exercise, the coach/confederate did not engage in any exercises but assumed a still position. Participants were instructed to observe the coach/confederate and to imagine that she would engage in the same exercise for 30 s. In the no-mimicry condition, after each exercise, the coach/confederate did not engage in any exercises either. However, in contrast to the other condition, participants were instructed to merely observe the coach/confederate, who remained in a natural resting position.

Afterward, in all three conditions, the main five-minute business training session on product and customer service, which was unrelated to the purpose of this study, was performed.

After the training, and regardless of the experimental condition, each participant was asked to assess his or her attitude to the coach/confederate by indicating agreement (1 = not at all; 7 = very much) with the following statement: “The coach is a nice and friendly person.” The coach left the room while participants were rating her. Finally, participants put the survey into a box, were debriefed, and dismissed.

Results

To investigate the effect of being mimicked on liking, we ran a one-way ANOVA. The results show that being mimicked affects liking for the coach/confederate, F(2, 57) = 5.75, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.17 (cf. Figure 1). A Tukey’s post-hoc test revealed significant differences between the visible mimicry (M = 6.35, SD = 0.88) and imagined mimicry condition (M = 5.55, SD = 1.05), t(57) = 2.47, p = 0.043, d = 0.83. This indicates that being able to see and perceive mimicry is a crucial precondition for the effect of being mimicked on liking to occur. Liking for the confederate also differed significantly between the visible mimicry condition (M = 6.35, SD = 0.88) and the no-mimicry condition (M = 5.3, SD = 1.13), t(57) = 3.24, p = 0.006, d = 1.04.

A final analysis revealed no statistical difference between the imagined mimicry condition (M = 5.55, SD = 1.05) and the no-mimicry condition (M = 5.3, SD = 1.13), t(57) = 0.77, p = 0.721, d = 0.23. To estimate the probability that our data would occur if the null hypothesis was true (i.e., there is no difference between the imagined mimicry and the no-mimicry condition), we ran a Bayesian t-test for independent samples using JASP software (JASP Team, 2021; Version 0.16) with the default priors (i.e., 0.707). This analysis yielded BF01 = 2.43, which can be considered as anecdotal evidence for H0 (Jeffreys, 1961).

Experiment 2

Replicating previous results reported in the literature (e.g., Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Kulesza et al., 2015; La France & Ickes, 1981; Lakin et al., 2003), Experiment 1 found that being mimicked increases liking for the mimicker. Moreover, the results demonstrate that merely imagining being mimicked does not produce the same effects as actually being mimicked. This indicates that participants need to actually experience mimicry to perceive another person as more likable.

An explanation for this result may be found in the already mentioned work of Oettingen and Wadden (1991), where it was reported that imagining not only a state, but also actions (in comparison to imagining a state only) that led to the expected outcome. In our study, participants only imagined the state.

Despite this implication, several limitations of Experiment 1 hinder drawing strong conclusions. First, Experiment 1 was rather underpowered with only sixty participants. Second, liking was measured with one item only, which is known to have low reliability (e.g., Epstein, 1980). Third, one could argue that the item we used did not measure liking per se but rather positive perceptions of the coach. Thus, in Experiment 2, we carried out a high-powered replication with a slightly modified procedure that allowed mass testing in an online setting.

Moreover, we decided to measure respondents’ liking toward the coach/confederate more directly and reliably by including multiple items. Finally, as in Experiment 1, the mimicker was a woman. In Experiment 2, we decided to test the generalizability of our effect by replicating it with a male mimicker.

Method

Participants and Design

We aimed to detect an effect size of at least d = 0.4, roughly corresponding to the average effect size obtained in psychological research. To detect such an effect with a power of 1—β = 0.8, and alpha-probability of α = 0.05, 100 participants per condition are needed. To this end, we recruited participants for an online experiment via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. 301 participants (114 women, 178 men, M age = 36.2, SD age = 11.0) with an age ranging from 20 to 72 agreed to participate in the experiment. Nine participants were excluded from the analyses because they reported that they did not engage in the relaxation exercises. Thus, the final sample consisted of 292 participants. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three between-subject conditions: visible mimicry, imagined mimicry, no-mimicry. As in Experiment 1, the gender distribution between the experimental conditions was not unequal: χ2 (2, N = 292) = 2.64, p = 0.267, V = 0.1.

Procedure

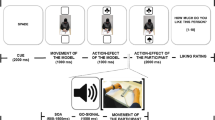

The procedure was very similar to that of Experiment 1. However, instead of manipulating mimicry in a face-to-face manner, we applied a procedure for online experiments by adapting video manipulations previously used in experiments on mimicry (e.g., Genschow & Alves, 2020; Genschow et al., 2017; Genschow, Klomfar, et al., 2018; Kulesza et al., 2015; Sparenberg et al., 2012). Although the disadvantage of such a video manipulation is a lack of real-life social interactions, it has several methodological advantages. First, in contrast to real-life situations, the confederates are blind to conditions and hypotheses and can thereby not influence the outcome of the manipulation. Second, the timing and performance of the confederates’ actions are the same across participants, which reduces noise.

In Experiment 2, participants had to engage in three different relaxation exercises for 15 s each: (1) massaging the temples with both hands, (2) moving the head up and down, and (3) moving shoulders up and down.

For each exercise, participants received separate written instructions. After each instruction, they had to engage in the respective exercise for 15 s. Depending on the condition, after each exercise, participants were presented with different stimuli. After each exercise, participants in the visible mimicry condition watched a video of a male model engaging in the same exercise for 15 s. Participants in the imagined mimicry condition were presented after each exercise with a photo of the same model for 15 s. In addition, they were instructed to imagine the model depicted in the photo engaging in the same exercise as they just did. Participants in the no-mimicry condition saw a photo of the same model for 15 s after each exercise but were instructed to merely look at the photo. All videos and photos are publicly accessible at the Open Science Framework (OSF: https://bit.ly/3tTpzFf).

After running through three trials, participants indicated how much they liked the model with four items adapted from Chartrand and Bargh (1999). That is, on 9-point rating scales, participants rated their agreement (1 = not at all; 9 = very much) with the following statements: “I find the other person likable”, “The other person is friendly”, “I like the other person”, “I think I could become friends with the other person.” To prepare data for analyses, we computed a mean score over all items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96).

To go along with the cover story, participants also reported how relaxed they felt by indicating their agreement on 9-point rating scales (1 = not at all; 9 = very much) with the following three statements: “After engaging in the exercises, I feel relaxed,” “The exercises calmed me down,” “After engaging in the exercises, I feel better than before.” To prepare data for analyses, we averaged the ratings across all items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). Finally, participants indicated if they actually engaged in the relaxation exercises and then indicated basic demographics.

Results

First, we analyzed whether mimicry had an effect on reported relaxation. A one-way ANOVA with the mimicry condition (visible mimicry vs. imagined mimicry vs. no-mimicry) as the independent variable and reported relaxation as the dependent variable did not yield a significant effect, F(2, 289) = 2.24, p = 0.108, ηp2 = 0.02. This indicates that there is no reason to believe that mimicry influences participants’ relaxation; visible mimicry (M = 7.13, SD = 1.43), imagined mimicry (M = 6.83, SD = 1.34), no-mimicry (M = 6.67, SD = 1.68). To estimate the probability that our data would occur if the null hypothesis was true (i.e., mimicry does not influence relaxation), we ran a Bayesian ANOVA for independent samples using the JASP software (JASP Team, 2021; Version 0.16) with the default priors (i.e., 0.707). This analysis yielded BF01 = 3.56, which can be considered moderate evidence for H0 (Jeffreys, 1961).

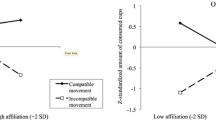

More important for our predictions, however, was the result of the ANOVA on indicated liking for the model. The results show that mimicry affected liking, F(2, 289) = 10.64, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07 (cf. Figure 2). A post-hoc test with Tukey’s correction revealed significant differences, t(289) = 2.73, p = 0.018, d = 0.45, between the visible mimicry (M = 6.57, SD = 1.64) and the imagined mimicry condition (M = 5.77, SD = 1.89). Liking of the models also differed significantly, t(289) = 4.61, p < 0.001, d = 0.65, between the visible mimicry (M = 6.57, SD = 1.64) and the no-mimicry condition (M = 5.26, SD = 2.27).

As in Experiment 1, there was no significant difference, t(289) = 1.86, p = 0.152, d = 0.24, between the imagined mimicry (M = 5.77, SD = 1.89) and no-mimicry condition (M = 5.26, SD = 2.27). To estimate the probability that our data on the comparison between the imagined mimicry and the actual mimicry condition would occur if the null hypothesis was true (i.e., there is no difference between the imagined mimicry and the no-mimicry condition), we ran a Bayesian t-test for independent samples using the JASP software (JASP Team, 2021; Version 0.16) with the default priors (i.e., 0.707). This analysis yielded BF01 = 1.57, which can be considered anecdotal evidence for H0 (Jeffreys, 1961).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 replicate the finding obtained in Experiment 1: being mimicked increases liking for the mimicker. For this effect to occur, individuals need to actually observe the other person mimicking. Merely imagining that the other person mimicking does not produce the same effect as actually being mimicked.

However, one may argue that the video manipulation we used to implement mimicry was perceived as artificial, which might have influenced our results. However, for several reasons, we regard the influence of the artificial setup on our effects as rather non-substantial. First, video manipulations are not uncommon in the mimicry literature and are known to produce similar effects as real-life interactions (e.g., De Coster et al., 2014; Genschow et al., 2017; Genschow, Klomfar, et al., 2018; Kulesza et al., 2015; Sparenberg et al., 2012). Second, the artificial nature of the mimicry condition did not seem to bother participants. At least, we did not find differences between the conditions in terms of indicated relaxation. Finally, even if the artificial nature of our manipulation would have had an influence on our results, this does not apply to Experiment 1, in which we applied a real-life situation and found the same results as in Experiment 2.

General Discussion

The goal of the present research was to test whether imagining being mimicked would influence the perception of the mimicker to the same extent as actually being mimicked. The results show that merely imagining being mimicked does not relate to liking in the same way as actually being mimicked does because being mimicked led to more liking than imagining being mimicked. This finding has several theoretical implications.

Theoretical Implications

Research on mental action simulation suggests that merely thinking of an action is neurophysiologically similar to actually engaging in that action (e.g., Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Greenwald, 1970; Prinz, 1997). From this point of view, one could have expected that imagining being mimicked leads to the same results as actually being mimicked. This is, however, not what we found. Instead, our results are in line with non-representational frameworks of imitation (e.g., Carr & Winkielman, 2014; Iacoboni, 2009). Such frameworks put forward that the involvement of higher-order constructs that map another’s actions onto one’s own body are not a necessary precondition for mimicry to occur. In line with this notion, our results suggest that in the domain of being mimicked, merely imagining being mimicked does not lead to the same effects as actually being mimicked. Indeed, recent research suggests that it is the visuo-spatial similarity between the mimicker’s and the mimickee’s action, and not the similarity in motor system activity per se that accounts for the mimicry-liking pathway (Casasanto et al., 2020). At the same time, it is important to note that our findings do not call into question mental simulation accounts. Our results merely suggest that the principles observed in mental simulation research do not apply to the domain of being mimicked. In other words, our results suggest that being mimicked and imagining being mimicked do not rely on the same principle as actually performing an action and imagining doing this action.

Another interesting finding of our research is that despite a very brief exposure to mimicry, we found an effect of mimicry on liking in both experiments. This illustrates how quickly the effects of being mimicked can unfold. In all of our experiments, mimicry exposure was just a few seconds long. This is very short when compared with the original Chartrand and Bargh (1999) experiments, which lasted approximately nine minutes. This finding not only has implications for the research on mimicry but also for research on social influence and implementation in real-life situations, such as in therapy, coaching, and workshops. Exposing individuals to nonverbal behavior for just a few seconds may be sufficient to affect receivers’ perception.

Finally, and related to the previous implication, from a practical point of view, mimicry is often applied in clinical psychology, where it has been shown that imitation helps to build a mutual understanding between psychotherapist and patients (Charny, 1966; Maurer & Tindall, 1983; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2011, 2014; Scheflen, 1964). Our research adds an important new quality as the effects may already be present after brief mimicry exposure.

Limitations and Further Directions

Besides these implications, there are several limitations that call for a thorough discussion. First, one may argue that in our experiments it may have been the instructions that were responsible for the differences in liking. Simply put, being asked to just watch a live person sitting still in a natural position (Experiment 1) or a photograph of a person sitting in a natural position (Experiment 2) could be perceived as unnatural and may trigger the participants to think about reasons for why the person is behaving in such a way. This extra cognitive effort or the unusual nature of the situation could have influenced participants’ mood and as a consequence affected the liking of the person being observed. However, it is important to note that in Experiment 2, we measured how relaxed participants were. As we did not find an effect of the mimicry manipulation on feelings of relaxation, we regard it as rather unlikely that our effects can be explained by differences in mood. Nevertheless, this alternative explanation of our findings leads to the broader question of whether any mimicry effect reported in the literature is driven by actual mimicry or due to the absence of mimicry.

It might well be that mimicry takes place in any natural social conversation and that the absence of such mimicking behavior is perceived as unnatural, thereby reducing prosocial attitudes and liking for the interaction partner. To the best of our knowledge, this explanation has never been rigorously tested. Thus, future research may investigate to what degree mimicry leads to an increase and/or the absence of mimicry to a decrease of prosocial attitudes and liking. While it remains open to what degree control conditions in mimicry experiments reduce liking for the interaction partner, it is important to note that this open question does not limit the main contribution of our research. From a mental action simulation point of view, one could have expected that imagining being mimicked would lead to the same degree of liking as when actually being mimicked. As this was not the case, we are confident in concluding that merely imagining being mimicked does not produce the same effects on liking as actually being mimicked does. Nevertheless, future research may aim to more rigorously test the contribution of the control condition in typical mimicry experiments.

Second, an alternative explanation of our findings could be that in the imagined mimicry condition, participants became aware of the link between mimicry and liking. As a consequence, participants might have responded with reactance by downgrading their liking ratings. However, it is important to note that previous research (e.g., Kulesza et al., 2016) investigating the role of awareness demonstrated that making participants aware of mimicry behavior does not influence their liking ratings. Only if participants are told that there is a connection between mimicry and liking does their liking of the confederate reduce. Thus, although participants in our experiments might have become aware of mimicry in the imagined mimicry condition, this should not have affected their liking ratings as long as they were not aware of the connection between mimicry and liking. Yet an open question is whether the imagined mimicry condition in the experiments reported here led to the same degree of awareness as the manipulation used in Kulesza et al.’s (2016) experiment. To answer this question, future research should probe participants for suspicion and test the degree to which awareness of mimicry influences the effects of mimicry in comparison to the effects of imagined mimicry.

Third, empirical studies on the consequences of imagining different states of affairs show that a key factor may be how easy it is to imagine certain states (Dahl & Hoeffler, 2004; Levav & Fitzsimons, 2006; Petrova & Cialdini, 2005). We did not test in our experiments whether it was easy or difficult for the respondents to imagine that someone would mimic them. This issue could be included in further research on imagined mimicry.

Fourth, we have to acknowledge that we did not investigate gender differences between participants and confederates. Although the number of male and female participants was similar in both experiments and the randomization worked as the ratio between male and female participants was equal across all experimental conditions, we did not manipulate whether participants interacted with a male or a female model. Rather, we varied the gender of the models across experiments. While participants interacted with a female model in Experiment 1, they interacted with a male model in Experiment 2. As we found the same effects in both experiments, we believe that gender does not contribute to a substantial degree to our results. Nevertheless, future research should address this issue more directly by varying the gender of the model within a single experiment.

Conclusions

Previous research indicates that being mimicked increases liking for the mimicker. Research on mental action simulation indicates that merely imagining an action is neurophysiologically similar to actually engaging in this action. Based on this finding, one might assume that imagining being mimicked leads to an increase in liking too. Our results clearly speak against this idea by demonstrating that merely imagining being mimicked does not relate to liking as much as actually being mimicked does.

References

Arnold, A. J., & Winkielman, P. (2020). The mimicry among us: Intra- and inter-personal mechanisms of spontaneous mimicry. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-019-00324-z

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall.

Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4), 577–660. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x99002149

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639

Carr, E. W., & Winkielman, P. (2014). When mirroring is both simple and “smart”: How mimicry can be embodied, adaptive, and non-representational. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00505

Casasanto, D., Casasanto, L. S., Gijssels, T., & Hagoort, P. (2020). The reverse chameleon effect: Negative social consequences of anatomical mimicry. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01876

Catmur, C., Walsh, V., & Heyes, C. (2007). Sensorimotor learning configures the human mirror system. Current Biology, 17(17), 1527–1531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.006

Charny, E. J. (1966). Psychosomatic manifestations of rapport in psychotherapy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 28(4), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-196607000-00002

Chartrand, T. L., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception–behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893

Cracco, E., Bardi, L., Desmet, C., Genschow, O., Rigoni, D., De Coster, L., et al. (2018). Automatic imitation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(5), 453–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000143

Dahl, D. W., & Hoeffler, S. (2004). Visualizing the self: Exploring the potential benefits and drawbacks for new product evaluation. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(4), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-6782.2004.00077.x

De Coster, L., Mueller, S. C., T’Sjoen, G., De Saedeleer, L., & Brass, M. (2014). The influence of oxytocin on automatic motor simulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.08.021

di Pellegrino, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (1992). Understanding motor events: A neurophysiological study. Experimental Brain Research, 91(1), 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00230027

Dimberg, U. (1982). Facial reactions to facial expressions. Psychophysiology, 19(6), 643–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1982.tb02516.x

Duffy, K. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (2015). Mimicry: Causes and consequences. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.03.002

Epstein, S. (1980). The stability of behavior: II. Implications for psychological research. The American Psychologist, 35(9), 790–806. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.9.790

Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Pavesi, G., & Rizzolatti, G. (1995). Motor facilitation during action observation: A magnetic stimulation study. Journal of Neurophysiology, 73(6), 2608–2611. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2608

Gazzola, V., & Keysers, C. (2009). The observation and execution of actions share motor and somatosensory voxels in all tested subjects: Single-subject analyses of unsmoothed fMRI data. Cerebral Cortex, 19(6), 1239–1255. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn181

Genschow, O., & Alves, H. (2020). The submissive chameleon: Third-party inferences from observing mimicry. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 88, 103966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.103966

Genschow, O., Bardi, L., & Brass, M. (2018a). Anticipating actions and corticospinal excitability: A preregistered motor TMS experiment. Cortex. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2018.04.014

Genschow, O., & Brass, M. (2015). The predictive chameleon: Evidence for anticipated social action. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 41(2), 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000035

Genschow, O., & Florack, A. (2014). Attention on the source of influence reverses the impact of cross-contextual imitation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035430

Genschow, O., Florack, A., & Wänke, M. (2013). The power of movement: Evidence for context-independent movement imitation. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 142(3), 763–773. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029795

Genschow, O., & Groß-Bölting, J. (2021). The role of attention in anticipated action effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 47(3), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000883

Genschow, O., Klomfar, S., d’Haene, I., & Brass, M. (2018b). Mimicking and anticipating others’ actions is linked to social information processing. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0193743. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193743

Genschow, O., & Schindler, S. (2016). The influence of group membership on cross-contextual imitation. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 23(4), 1257–1265. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0983-4

Genschow, O., van Den Bossche, S., Cracco, E., Bardi, L., Rigoni, D., & Brass, M. (2017). Mimicry and automatic imitation are not correlated. PLoS ONE, 12(9), e0183784. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183784

Greenwald, A. G. (1970). Sensory feedback mechanisms in performance control: With special reference to the ideo-motor mechanism. Psychological Review, 77(2), 73–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0028689

Hess, U., & Fischer, A. H. (2016). Emotional Mimicry in Social Context. Cambridge University Press.

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604

JASP Team. (2019). JASP (Version 0.9.2). Computer Software. JASP Team.

Jeffreys, H. (1961). Theory of Probability. Clarendon Press.

Keysers, C., & Gazzola, V. (2010). Social neuroscience: Mirror neurons recorded in humans. Current Biology, 20(8), 353–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.013

Kulesza, W. M., Cisłak, A., Vallacher, R. R., Nowak, A., Czekiel, M., & Bedynska, S. (2015). The face of the chameleon: The experience of facial mimicry for the mimicker and the mimickee. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(6), 590–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2015.1032195

Kulesza, W., Dolinski, D., & Wicher, P. (2016). Knowing that you mimic me: The link between mimicry, awareness and liking. Social Influence, 11(1), 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2016.1148072

Kulesza, W., Dolinski, D., Huisman, A., & Majewski, R. (2014a). The echo effect: The power of verbal mimicry to influence prosocial behavior. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x13506906

Kulesza, W., Szypowska, Z., Jarman, M. S., & Dolinski, D. (2014b). Attractive chameleons sell: The mimicry-attractiveness link. Psychology and Marketing, 31(7), 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20716

LaFrance, M. (1982). Posture mirroring and rapport. In M. Davis (Ed.), Interaction Rhythms: Periodicity in Communicative Behavior. Human Sciences Press.

LaFrance, M., & Ickes, W. (1981). Posture mirroring and interactional involvement: Sex and sex typing effects. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 5(3), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00986131

Lakin, J. L., Jefferis, V. E., Cheng, C. M., & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). The chameleon effect as social glue: Evidence for the evolutionary significance of nonconscious mimicry. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27(3), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025389814290

Levav, J., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2006). When questions change behavior: The role of ease of representation. Psychological Science, 17(3), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01687.x

Maurer, R. E., & Tindall, J. H. (1983). Effect of postural congruence on client’s perception of counselor empathy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(2), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.30.2.158

Meier, B. P., Schnall, S., Schwarz, N., & Bargh, J. A. (2012). Embodiment in social psychology. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4(4), 705–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01212.x

Mukamel, R., Ekstrom, A. D., Kaplan, J., Iacoboni, M., & Fried, I. (2010). Single-neuron responses in humans during execution and observation of actions. Current Biology, 20(8), 750–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.045

Oettingen, G., & Wadden, T. A. (1991). Expectation, fantasy, and weight loss: Is the impact of positive thinking always positive? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 15(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01173206

Pascual-Leone, A., Nguyet, D., Cohen, L. G., Brasil-Neto, J. P., Cammarota, A., & Hallett, M. (1995). Modulation of muscle responses evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation during the acquisition of new fine motor skills. Journal of Neurophysiology, 74(3), 1037–1045. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1037

Petrova, P. K., & Cialdini, R. B. (2005). Fluency of consumption imagery and the backfire effects of imagery appeals. The Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1086/497556

Prinz, W. (1997). Perception and action planning. The European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 9(2), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/713752551

Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2011). Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023419

Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2014). Nonverbal synchrony of head- and body-movement in psychotherapy: Different signals have different associations with outcome. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 979. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00979

Scheflen, A. E. (1964). The significance of posture in communication systems. Psychiatry, 27, 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1964.11023403

Seibt, B., Mühlberger, A., Likowski, K. U., & Weyers, P. (2015). Facial mimicry in its social setting. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01122

Semin, G. R., & Smith, E. R. (2008). Embodied Grounding: Social, Cognitive, Affective, and Neuroscientific Approaches. Cambridge University Press.

Sparenberg, P., Topolinski, S., Springer, A., & Prinz, W. (2012). Minimal mimicry: Mere effector matching induces preference. Brain and Cognition, 80(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2012.08.004

Stel, M., & Vonk, R. (2010). Mimicry in social interaction: Benefits for mimickers, mimickees, and their interaction. British Journal of Psychology, 101(2), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609x465424

Swaab, R. I., Maddux, W. W., & Sinaceur, M. (2011). Early words that work: When and how virtual linguistic mimicry facilitates negotiation outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(3), 616–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.01.005

Topolinski, S. (2012). The sensorimotor contributions to implicit memory, familiarity, and recollection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(2), 260–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025658

Topolinski, S., & Boecker, L. (2016). Minimal conditions of motor inductions of approach-avoidance states: The case of oral movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(12), 1589–1603. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000217

van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Kawakami, K., & van Knippenberg, A. (2004). Mimicry and prosocial behavior. Psychological Science, 15(1), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01501012.x

van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Steenaert, B., & van Knippenberg, A. (2003). Mimicry for money: Behavioral consequences of imitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(4), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00014-3

Wang, Y., & de Hamilton, A. F. C. (2012). Social top-down response modulation (STORM): A model of the control of mimicry in social interaction. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00153

Funding

This research was supported by: NCN (Narodowe Centrum Nauki – Polish National Science Centre), Preludium Bis 1 grant, granted to Wojciech Kulesza (Number: 2019/35/O/HS6/00420). Open access of this article was financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the 2019–2022 program, Regional Initiative of Excellence", Project Number 012/RID/2018/19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kulesza, W., Chrobot, N., Dolinski, D. et al. Imagining is Not Observing: The Role of Simulation Processes Within the Mimicry-Liking Expressway. J Nonverbal Behav 46, 233–246 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-022-00399-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-022-00399-1