Abstract

Rising disease prevalence early during the COVID-19 pandemic in the State of Qatar led to stoppage of all non-emergency health care services. To maintain continuity of care and information exchanges for non-emergency patients, a physician-operated telephone hotline was set up that involved triage followed by immediate consultation with a specialized physician. We describe the initiation and evaluate the operations of the Urgent Consultation Centre (UCC) hotline manned by 150 physicians and aimed at urgent non-life-threatening consultations at Hamad Medical Corporation, the public health provider in Qatar. UCC established a hotline to triage inbound patient calls related to 15 medical and surgical specialties. For calls between April-August 2020, we describe call volume, distribution by specialty, outcomes, performance of UCC team, as well as demographics of callers. During the study period, UCC received 60229 calls (average 394 calls/day) from Qatari nationals (38%) and expatriates (62%). Maximum total daily calls peaked at 1670 calls on June 14, 2020. Call volumes were the highest from 9 AM to 2 PM. Response rate varied from 89% to 100%. After an initial telephone triage, calls were most often related to and thus directed to internal medicine (24.61%) and geriatrics (11.97%), while the least percentage of calls were for pain management and oncology/hematology (around 2% for each). By outcome of consultation, repeat prescriptions were provided for 60% of calls, new prescriptions (15%), while referrals were to outpatient department (17%), emergency department/pediatric emergency center (5%), and primary health care centres (3%). We conclude that during a pandemic, physician-staffed telephone hotline is feasible and can be employed in innovative ways to conserve medical resources, maintain continuity of care, and serve patients requiring urgent care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, ways of taking care of one’s health and the relationships with a physician changed [1]. To lower the number of confirmed cases and reduce pressure on hospitals, the lockdown went into effect [2]. As most countries implemented the lockdown, providers across all specialties rapidly embraced the use of telehealth/ telemedicine [3] to maintain the continuity of health services and avoid missing emergency conditions, while minimizing face-to-face visits [4]. Such move from traditional care to virtual health became critical to protect patients, clinicians and the community from exposure, whilst providing a platform for providers and patients to interact at any time [5, 6]. In response, in the State of Qatar, with the start of the pandemic, Hamad Medical Corporation, the public tertiary care provider, initiated a dedicated Urgent Consultation Center (UCC) hotline to triage, consult, identify diseases, and treat /or refer according to the condition’s urgency [7].

Research has recognized the effectiveness of hotlines. For example, telephone delivered psychotherapy was similar to traditional face-to-face therapy [8], and hotlines provided specialized mental health support [9]. Hotlines overcome geographical isolation [10], stigmatization, transportation [11], reduce the pressure of consultation and provide a safe environment to express emotions [12]. Unsurprisingly, hotlines are a very popular crisis-intervention measure globally [13].

Telephone helplines are well-established conduits for mental health protection and suicide prevention, offering immediate, anonymous, cheap and accessible support [14]. Likewise, hotlines provide information about resources e.g., emergency shelter, emotional support, and help in safety planning [15]. In Egypt, calling the hotline was one of the most frequent practices to deal with COVID-19 symptoms [16]. In New York, a hotline was chosen over formal types of virtual medical appointments (e.g., telehealth) as it was widely accessible (anyone could call regardless of literacy level/ socioeconomic status); there was no cost, registration, appointment, or insurance verification, making it easy for patients and easing the burden on emergency medical services; and relying on a telephone eliminated technology barriers and facilitated clinician participation on short notice [17]. Hence, due to the unique characteristic of the epidemic, hotlines have become the most convenient way of rescue.

During COVID-19, hotline services were implemented in many countries [2, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Likewise, hotline services spanned many individual healthcare specialties, providing support/health information for conditions including COVID-19 [17, 30], suicide prevention [13], dermatology [31], mental health [21, 29, 32], sexual assault [33], dialysis/transplant [18], child abuse/neglect [34], or dental care [4, 6].

Notwithstanding, the literature reveals knowledge gaps. First, most studies reported hotline service/s operated by non-physicians. These included triage nurses [35], nurse specialists [31], trained volunteers [13], trained volunteers supervised by health professionals [36], counselors [2, 37], psychotherapeutically trained counselors [38], psychologists/clinical psychologists with psychotherapist qualifications [32], law enforcement/social service agencies [15], or operators [39]. In China, most of the 36 psychological assistance hotlines during the COVID-19 epidemic were manned by counselors with some qualifications, certified by different institutions, received different training and supervision, and their experience varied widely [40].

Second, clinician-staffed hotlines are rare, and when reported, such hotlines were limited to COVID-19 support. In New York, a clinician-staffed COVID-19 hotline was established, but no details were provided on who such staff were [17]. Similarly, a physician-staffed COVID-19 hotline included social care referrals for patients requiring to self-isolate [30].

Third, most hotlines were established for a single condition, rather than the broader spectrum of medical and surgical specialties. e.g., abortion [41], psychological support [38, 39], opioid use disorder [42], combating COVID-19 [43], domestic violence [44], inflammatory bowel disease [45], or respiratory support [46].

Therefore, to bridge these knolwedge gaps, the current service evaluation describes the initiation and inauguration of a UCC hotline manned by physicians to triage and respond to all medical and surgical specialties during the first five months of the COVID-19 lockdown in Qatar. We analyzed the caller, call and specialty characteristics, as well as call outcomes of all hotline calls across 15 medical/surgical specialties.

Materials and Methods

Ethics, Design, and Participants

Our hospital institutional review board provided approval for this service evaluation. It is a retrospective analysis of data routinely collected as a component of service evaluation/ audit. A total of 77,217 calls were received. We excluded COVID-19-related/general information queries (N = 16,988, 22%), leaving 60,229 calls that are included in this analysis.

Setting

Healthcare Landscape in Qatar

The Ministry of Public Heath (MOPH) is the supreme healthcare authority in Qatar. Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) is the largest public healthcare provider and oversees the 12 public hospitals. There are 27 primary health care centers (PHCC) in Qatar, and many private clinics and hospitals.

By mid-March 2020, in response to COVID-19 pandemic, Qatar implemented restrictions to limit viral transmission. For public healthcare, all outpatient visits were converted to telehealth. Physicians called the registered patients at the time of their appointment. Elective surgeries, except oncology-related, were stopped; and emergency departments (ED) were limited to life-threatening conditions. Many public hospitals/PHCC were converted to COVID-19 facilities. Likewise, all private clinics were temporarily closed and most private hospitals halted their activities.

These restrictive measures, however, resulted in an increased likelihood of disruption of continuity of care for some patients with urgent non-emergency conditions e.g., (1) patients with new non-COVID-19 complaints with no hospital appointment; (2) chronic patients experiencing changes in co/morbidities with no hospital appointment at a near date; (3) patients developing side effects to treatment/s; (4) chronic patients who missed their outpatient department (OPD) appointments and needed medication refill/s; and, (5) visitors in Qatar with no access to public healthcare. Before the pandemic, such patient groups could use public healthcare as walk-in, or use private healthcare.

Procedures

Creation of the Urgent Consultation Center (UCC)

HMC recognized this risk of disruption and the need for a healthcare hotline, the UCC, to: (1) provide safe care access for patients with urgent non-life-threatening conditions; (2) identify high-risk patients needing emergency intervention/s but afraid of infection; and, (3) avoid unnecessary hospitals visits to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission to healthcare providers/patients. A steering committee was assigned to create the UCC and necessitated several steps, as outlined below.

Workspace

Workspace (300 m2) in an HMC administrative building, purposively chosen away from the patient areas, was allocated to accommodate the triage/specialty physicians of all medical/surgical specialties. The workspace was in accordance with COVID-19 regulations: each area staffed with a maximum of 8 persons, at least 2 m apart; fiberglass sheets separated the desks; COVID-19 screening and temperature measuring were undertaken on entry to office areas before every shift; personal protection equipment, sanitizers and hand wash were used; thorough regular sanitization of the desk areas and computers etc. was undertaken; and, staff stopped using the biometry attendance machines.

Communication/Information Technology (IT)

The Ministry of Communications provided a hotline number for UCC. HMC’s IT department installed computers with access to the hospitals’ patient hospital information system (HIS), and connected the landline telephones.

Staffing

Fifteen triage physicians were hired and trained on the use of hospital technology (operation system, Cisco phones, etc.), creation of UCC encounter, telehealth communication skills, and hospital policies (patient rights/ privacy). In addition, each HMC department assigned attending senior physicians (consultants/specialists) to the UCC, chosen for their ability to assess the urgency of the calls, and appropriately serve patients through teleconsultation.

Advertising/Promotion

HMC’s Communications Department initiated a campaign across media outlets (newspapers, television, radio) and social media platforms to popularize UCC, orienting the general public about the service.

Workflow at UCC

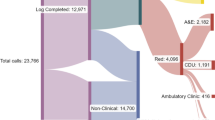

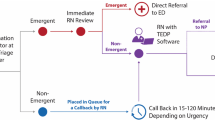

Patients would call the tollfree hotline (Fig. 1). Triage doctors attended the call, identified the patient, and carefully assessed the query/complaints using the triage physician protocol (Fig. 2). Calls were then directly connected to the relevant specialty physician. Triage physicians managed general guidance calls and referred COVID-19-related calls to the MOPH/COVID-19 helpline.

Specialty physicians then assessed the patient’s condition, managed accordingly based on the specialty physician protocol, and documented the information in the hospital HIS (Fig. 3). Life-threatening or suspected emergency cases were guided to call emergency medical services (EMS) or go to the ED/Pediatric Emergency Center (PEC). Physician’s recommendations were entered in the HIS to facilitate patient access to the ED. Non-life-threatening cases were served as regular OPD appointments. Physicians could order investigations, write/refill prescription/s, or refer patients to the OPD (routine/urgent). UCC’s OPD referrals were considered as triaged, with faster appointment booking. To ensure uniform high-quality service, telehealth protocols were developed for the triage and specialty physicians. (Figures 2 and 3). Appropriate documentation was entered in HIS in compliance with hospital documentation policies.

Quality Assurance

Despite that the UCC was created during an extra-ordinary pandemic, efforts were invested in maintaining the highest healthcare service quality, in line with the patient charter and Joint Commission International (JCI). Thorough patient identification before disclosing any medical information ensured patient privacy and that the physician was speaking to the correct patient/legal guardian. The only exception to this rigorous process was for calls requiring psychiatry/mental health services. As per the psychiatry department’s protocol, patient identification was not undertaken hence ensuring patient privacy and preventing stigma. Where medications/investigations were ordered, patient identification was undertaken prior to ordering. Physicians were assigned desks ≥ 2 m apart, with separators to avoid overhearing. Headphone and microphone sets were used during calls, and loudspeaker use during hotline consultation was not allowed.

Proper documentation of calls in HIS was audited daily in accordance with JCI standards. Visit notes included annotations confirming the virtual UCC consultation to assist the fast tracking of patients referred to OPD/ED/PEC. Patient waiting time until answered by the triage and specialty physicians was monitored to avoid unnecessary waiting; as well as audit of any missed calls, so that they could be called back during the same shift. All calls were recorded for service quality and to ensure high patient satisfaction.

Refining the UCC Service

The interactive dynamic model of the UCC operations was premised on analysis of the challenges encountered and workflow statistics, and changes were implemented accordingly as outlined below:

Working Hours

Initially, UCC working hours were 7am-10 pm, 7 days/week, however, as < 40 calls were received on Fridays, this schedule was changed to 6 days/week. During the holy month of Ramadan, calls decreased towards the end of the morning shift, leading to a further modification (2 shifts, 5 h each, morning 8am-1pm, evening 7pm-12am).

Interpretation

Qatar’s demography comprises 85% expatriates. Most people communicate in Arabic or English. However, once language barriers were identified during the calls, UCC assigned Indian, Malayalam and Urdu speaking Asian nurses for interpretation.

Document/Photo Sharing

Some patients wished to share photos with the attending physician (e.g., skin/oral lesions, old prescriptions, etc.). Hence, two dedicated mobile phones equipped with WhatsApp were allocated to the UCC. After any call, all files were immediately deleted from the mobile phones thus maintaining patient privacy.

Additional Medical Specialties

UCC initially included 11 specialties. Two weeks after its inauguration, based on patient demand, four more specialties were added (neurology, pain management, geriatric medicine, and oncology/hematology).

Additional Staff Subject to Call Volume

Based on call volume per specialty, additional attending physicians were recruited to avoid long waiting times and assist in returning any unattended calls. An example was the general medicine specialty, where 4 physicians instead of the traditional 2 were assigned per shift.

Medical Store Requests and Prescriptions

For chronic patients, store requests are needed for consumables (e.g., catheters, urine bags, etc.). Agreement with the HMC store allowed dispensing consumables to patients based on emailed store request copies from UCC. Likewise, for written prescriptions of selected medications not supplied by HMC pharmacy, MOPH issued changes allowing the use of an electronic copy of the prescription sent to patient via WhatsApp. In addition, agreement with HMC pharmacy bypassed the narcotic/antipsychotic prescriptions problem by daily written prescriptions sent from UCC to the narcotics pharmacy. Patients would then collect it after appropriate identification. HMC pharmacy also started free home delivery for all prescribed medications using the Qatar Post service. UCC physicians guided patients to this service.

Health Cards

Visitors to Qatar did not have health cards, and could not be served by UCC (cannot be registered into the system). The Patient Registration department granted access to UCC coordinators to create health card numbers for such patients permitting access to public healthcare.

UCC Encounter Code

Each patient visit to HMC is registered by clerks as an encounter. UCC, being a new service, had no encounter for the service. As UCC is physician-operated, the IT department generated a UCC-specific encounter code, created by triage physicians during the call, ensuring appropriate patient documentation/registration.

Results

Physician Characteristics

The 15 triage physicians were new medical graduates with 1–5 years experience, and age range 28–32 years. The 150 specialty physicians were senior staff with 6-45year experience, and age range 30-75years.

Caller Characteristics

Qatari nationals comprised about a third of the callers, patients’ median age was 46 years, and males comprised 50.7% of callers (Table 1). Callers’ sex differed by specialty (females 100% in obstetrics/gynecology, 13.3% in urology) (Table 2). Most calls (89%) were in Arabic or English language, with interpretation required for only 11% of calls.

Call Characteristics

The response rate varied from 89 to 100%, with different monthly rates per specialty (Table 3). The maximum total daily calls peaked at 1670 calls on June 14, 2020. Call volumes were the highest from 9 am-2 pm. Median call waiting time before the triage physician answered was 1.5 min (range 1–12 min). As for the different specialties, median call waiting was 3.5 min (range 1.5–24 min).

Specialty Characteristics

Fifteen specialties were covered by UCC. During the study period, UCC received 60,229 calls (average of 394 calls/day). After initial telephone triage, callers were most often directed to internal medicine (24.61%), geriatrics (11.97%), cardiology (8.72%), gynecology (8.66%), psychiatry (6.79%), orthopedics (6.59%), dermatology (5.30%), urology (5.13%), neurology (4.29%), and pediatrics (3.99%); while other specialties included general surgery, ENT and dental (each 3%); and around 2% for each of pain management and oncology/hematology (Fig. 4). The call volume and ranking of the specialties based on total monthly calls differed by month (Fig. 5). Figure 6 shows the fluctuation of calls with time for the various specialties, illustrating a spike increase during June due to the second wave of COVID-19.

Outcomes

Analysis by outcome of the consultation showed that the majority of calls were truly non-emergency, with repeating prescriptions being the most provided service (60% of calls). However, 5% of calls were true emergencies were the patient was advised to go to ED/PEC (5%) immediately (Fig. 7).

Table 4 depicts the outcome of the calls by specialty. The highest volumes of medication refills were for medicine and geriatrics specialties (51.19%), followed by neurology and orthopedics. As for new prescriptions, the most common were medicine and dermatology (42.04%), followed by obstetrics-gynecology and ENT. In terms of referrals, OPD referrals were most common from orthopedics (33.57%) followed by medicine and surgery (24.58%); referrals to PHCC were most common from dentistry and medicine (47.63%) followed by obstetrics-gynecology. Referrals to emergency department were most common from obstetrics-gynecology, pediatrics, medicine (54.41%) followed by cardiology and surgery.

Discussion

In this service evaluation report, we described the feasibility, organization and effectiveness of a large-scale physician-staffed hotline providing care and disseminating information to a country-wide general population and patients requiring urgent care amidst a global pandemic. The main findings were that, during the five months under examination, about 60,000 patients called the hotline, were triaged and immediately connected to physicians specialized in 15 different medical and surgical specialties. As the volume of calls to the UCC hotline surged, the ability of the UCC’s 150 triage physicians manning the hotline to answer calls as they came in varied from 89 to 100%. For 75% of callers, repeat and new prescriptions (60% and 15% of calls respectively) were the reason for the call and were provided, thus maintaining a seamless continuity of care with no additional exposure risk to COVID-19 virus in terms of an uninterrupted flow of critically required medications and crucial essential treatments to patients.

As regards the technology, perhaps the key to the success of hotlines is their relative simplicity compared to other modes of remote telemedicine. We agree that telephone hotlines entail modest technological competencies, can be instigated swiftly, and are available to those who have no internet access, particularly when facilities with public internet e.g., libraries/ wi-fi cafes are inaccessible due to the lockdown [30]. Indeed, UCC’s hotline was set up in seven days as the technology required was feasible and swiftly provided a synchronous and efficient real-time interactive health service. Others have observed that telephone calls have comparable patient health outcomes as video-based appointments [47]. As illustrated in setting up the UCC in Qatar, early during the pandemic, only the audioconferencing approach was initially available, hence remote consultations were limited to telephone consultations [48].

In terms of manpower and competencies, the physicians who manned the UCC hotline comprised generalists for the triage who then transferred the call accordingly to specialist and consultant physicians, surgeons and dentists selected to reflect the abilities and expertise required for the task. Others have highlighted that the workforce could be selected for their expertise [49]; and telephone advice depends on an appropriately skilled workforce who are accessible to sort out and settle calls over the phone, with attention to patients’ emotional and medical needs [50]. Most studies reported hotline service/s that were manned by non-physicians e.g., nurses, volunteers, counselors, psychologists, social service agencies or operators [2, 13, 15, 32, 35, 39]. The competencies of such a variety of operators would cover, to an extent, some ‘hard’ skills e.g., basic knowledge and intervention skills, as well as a wider range of ‘soft’ skills e.g., “ability to build a relationship with the callers effectively,” “quickly focus on the major complaint of the callers and form the primary intervention plan,” and “ability to identify and respond to emergencies and nuisance calls” [40]. Nevertheless, such level of competencies would be different from those of a fully trained physician conducting the triage at UCC or specialized physicians by specialty conducting the consultations as seen in the current report. Physician-staffed hotlines are very scarce in the literature, mostly limited to COVID-19 service, e.g. [30]. In this respect, Qatar’s UCC is truly unique as it was physician-staffed and serviced all medical and surgical specialties. Research is required to establish the necessary skill level and education, and the decision support strategies to ensure uniform, appropriate and safe care via telephone advice [51].

As a health service model during a pandemic, the present innovative UCC model confirms that robust, comprehensive, and hospital-integrated hotline-based telehealth is a viable health service model during the acute phase of a pandemic. The timely initiation of UCC, and the subsequent adjustments and refinements to its operations as highlighted above, provide support that during the period of practice reconfiguration world-wide, the renewed interest for hotline telemedicine led to promising service delivery changes [52]. Across the volume of calls received by UCC, the mean waiting time for a call to be answered was 1-1.5 min, which was excellent. In addition, after the call was answered and connected to the required specialty, about 75% were resolved successfully (only ≈ 25% of calls were referred). These findings agree with that telephone advice can deliver appropriate and timely clinical response for some patients, settling low acuity calls [49]; and, a systematic review of telephone advice observed that clinician advice and disposition assigned were both safe and appropriate [51]. UCC was successful in limiting face-to-face visits to the hospital, as the service managed the complaints of about 45,000 patients remotely, significantly reducing the number of patients who would have otherwise physically visited various HMC facilities. Others noted similar findings [4].

In terms of referrals, 25% of calls were referred, comprising mainly to outpatient departments (17%), while referrals to emergency departments and PHCC were minimal (5% and 3% respectively). This highlights that even when referrals were undertaken, only 5% required the urgency and skills available in an emergency department. This is critical, given that many emergency departments were dealing with COVID-19 cases. Our observations support findings reported elsewhere: on the one hand, patients need to avoid delaying necessary medical care during the pandemic, especially in emergency situations [53]; on the other hand, individuals are advised to avoid unnecessary healthcare use to reduce transmission of the virus and ensure that hospital capacity can accommodate surges in COVID-19 cases [54].

As a future post-pandemic health service model, the UCC hotline model has promise and future implications. The savings in healthcare provider and patient time, effort, transport and pressure on the healthcare system that a robustly-set and operated hotline offers definitely need to be considered after the pandemic has subsided. Hotlines will most probably be a permanent ‘modus operandi’ for the future that is both cost and clinically effective. The longer-term prospect of hotlines telemedicine is likely to persist after the pandemic’s acute stages [52].

The current report has some limitations. Missing data are not uncommon in retrospective inquiries of data routinely collected as part of service audit. Likewise, others have raised some concerns about the consistency of data reporting for calls resolved over the phone [55], and the current study is no exception. Although research exists on the demographic characteristics of e.g., persons calling for dental care [4], the current report, akin to other reports that employed administrative data about calls, is not in a position to remark on the features of the callers who made the calls [15]. A breakdown of emergency conditions detected and referred to the emergency department by the hotline would have been useful to provide an indication of the impact of the hotline in the detection of emergency cases and hence saving lives. However, the data to undertake this task is unavailable.

Notwithstanding, the current report has many strengths. It assessed all calls to a new broad-scope service provided to a whole country, covering all specialties. We analyzed routinely collected information on the total calls to a national hotline covering the whole nation, where other studies examined only city-wide [17] or state-wide [35] initiatives. Hence it is wide scale and the calls captured are representative of the demographically and ethnically diverse population in Qatar as HMC is the main public tertiary care provider. Calls comprised nationals and the breadth of the multinational populations that are resident in Qatar with different ethnic and genetic backgrounds, rendering generalization of the findings feasible. In addition, the report appraised all calls, and research employing the total population of calls for a hotline service that serves all specialties of healthcare, as we undertook, is not common, e.g., [15]. Likewise, we evaluated a service that encompassed all healthcare specialties, where other studies were only COVID-19-specific or appraised single condition/disease or individual healthcare specialties, e.g., [13, 31, 33]. The report also provides information across the complete period of the first lockdown, furnishing a broad view across five months.

Conclusion

The high call volume highlights the demand on and the utility of the UCC in bridging the unavoidable gaps that emerged during the pandemic, thus ensuring a smooth transition and continuity of care. The hotline data underline the importance of having a consistent, trustworthy and specialized source of care and information across all healthcare specialties for the public and patients when other services are unavailable. With adequate resources and much coordination, the service setup as well as its operations ran smoothly, and the triage physicians as well as the physicians in the different specializations were able to deliver UCC’s objectives. The findings provide valuable insights on the nature of the process and key challenges for other similar settings instigating hotline services.

References

A. Frankowska, M. Szymkowiak, D. Walkowiak. Teleconsultations Quality During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland in the Opinions of Generation Z Adults, Telemed J E Health Apr 20 (2022), Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0552.

E. Humer, C. Pieh, T. Probst, I.M. Kisler, W. Schimböck, P. Schadenhofer, Telephone Emergency Service 142 (TelefonSeelsorge) during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross- Sectional Survey among Counselors in Austria, Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (5) (2021) 2228, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052228.

N.M. Giunta, P.S. Paladugu, D.N. Bernstein, M.C. Makhni, A.F. Chen, Telemedicine Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Experience During COVID-19, J Arthroplasty Mar 4 (2022) S0883- 5403 (22) 00257-1, Online ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.106.

S.A. Ali, A.M.A. Al-Qahtani, S.R. Al Banai, F.J. Albaker, A.E. Almarri, K. Al-Haithami, M.N. Khandakji, W. El Ansari, Role of Newly Introduced Teledentistry Service in the Management of Dental Emergencies During COVID-19 Pandemic in Qatar: A Cross- Sectional Analysis, Telemed J E Health Mar 24 (2022), Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0584.

S. Garfan, A.H. Alamoodi, B.B. Zaidan, et al., Telehealth utilization during the Covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Comput Biol Med. Nov (138) (2021) 104878, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104878.

S.A. Ali, W. El Ansari. Is tele-diagnosis of dental conditions reliable during COVID-19 pandemic? Agreement between tentative diagnosis via synchronous audioconferencing and definitive clinical diagnosis. J Dent. Jul (122) (2022) 104144. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104144. Epub 2022 Apr 26.

Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), COVID-19 Hotline 16000. Published online 2021. Accessed May 5, 2022 https://www.hamad.qa/EN/COVID19/Pages/default.aspx, 2021.

D.C. Mohr, J. Ho, J. Duffecy, D. Reifler, L. Sokol, M.N. Burns, L. Jin, J. Siddique, Effect of telephone administered vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients: a randomized trial, JAMA 307 (21) (2021) 2278–85, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5588.

L.J. Biggs, H.L. McLachlan, T. Shafie, P. Liamputtong, D.A. Forster, ‘I need help’: reasons new and re-engaging callers contact the PANDA-perinatal anxiety and depression Australia National Helpline, Health Soc Care Commun. 27 (3) (2019) 717–28, https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12688.

T. Lavender, Y. Richens, S.J. Milan, R.M. Smyth, T. Dowswell, Telephone support for women during pregnancy and the first six weeks postpartum, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7 (2013) CD009338, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

C.L. Dennis, D. Kingston, A systematic review of telephone support for women during pregnancy and the early postpartum period, J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 37 (3) (2008) 301–14, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00235.x.

K.S. Fugl-Meyer, H. Arrhult, H. Pharmanson, A.C. Backman, A.M. Fugl-Meyer, A.R. Fugl-Meyer, A Swedish telephone help-line for sexual problems: a 5- year survey, J Sex Med. 1 (3) (2004) 278–83, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.04040.x.

F.F. Shaw, W.H. Chiang, An evaluation of suicide prevention hotline results in Taiwan: caller profiles and the effect on emotional distress and suicide risk, J Affect Disord. Feb 1 (244) (2019) 16–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.050.

C. M. Coveney, K. Pollock, S. Armstrong, J. Moore, Callers’ experiences of contacting a national suicide prevention helpline, Crisis 33 (6) (2012) 313–324, https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000151.

S.B. Sorenson, L. Sinko, R.A. Berk, The Endemic Amid the Pandemic: Seeking Help for Violence Against Women in the Initial Phases of COVID-19, J Interpers Violence 36 (9–10) (2021) 4899–4915, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521997946.

N. Sabry, S. ElHadidi, A. Kamel, M. Abbassi, S. Farid, Awareness of the Egyptian public about COVID-19: what we do and do not know, Inform Health Soc Care 46 (3) (2021) 244–255, https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2021.1883029.

R. Kristal, M. Rowell, M. Kress, C. Keeley, H. Jackson, K. Piwnica-Worms, L. Hendricks, T.G. Long, A.B. Wallach, A Phone Call Away: New York’s Hotline And Public Health In The Rapidly Changing COVID-19 Pandemic, Health Aff. 39 (8) (2020) 1431–1436, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00902.

Y.A. Arevalo, A.L. Murillo, E.W. Ho, S.M. Advani, L. Davis, A.F. Lipsey, M. Kim, A.D. Waterman, Stressors and Information-Seeking by Dialysis and Transplant Patients During COVID-19 Reported on a Telephone Hotline: A Mixed Methods Study, Kidney Med. May 10 (2022) 100479, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xkme.2022.100479.

S.A. Elliott, E.S. Bardwell, K. Kamke, T.M. Mullin, K.L. Goodman, Survivors’ Concerns During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Insights From the National Sexual Assault Online Hotline, J Interpers Violence Mar 26 (2022) 8862605221080936, https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221080936.

B.A.Y. Cher, E.A. Wilson, A.M. Pinsky, R.F. Townshend, A.V. Wolski, M. Broderick, A.M. Milen, A. Lau, A. Singh, S.K. Cinti, C.G. Engelke, A.K. Saha, Utility of a Telephone Triage Hotline in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Observational Study, J Med Internet Res. 23 (11) (2021) e28105, https://doi.org/10.2196/28105.

J. An, Y. Yin, L. Zhao, Y. Tong, N.H. Liu, Mental health problems among hotline callers during the early stage of COVID-19 pandemic, PeerJ. May 23 (10) (2022) 10:e13419, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13419.

Y. Tong, K.R. Conner, Y. Yin, L. Zhao, Y. Wang, M. Wu, C. Wang, Suicide attempt risks among hotline callers with and without the coronavirus disease 2019 related psychological distress: a case-control study, BMC Psychiatry 21 (1) (2021) 363, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03371-3

A. Mahmoodpoor, A. Shamekh, S. Sanaie, A Debate on Vitamin C: Supplementation on the Hotline for Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19, Adv Pharm Bull. 11 (3) (2021) 395–396, https://doi.org/10.34172/apb.2021.046.

S.B. Alzahrani, A.A. Alrusayes, Y.K Alfraih, M.S. Aldossary, Characteristics of paediatric dental emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia, Eur J Paediatr Dent. 22 (2) (2021) 95–97, https://doi.org/10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.02.2.

R. Inokuchi, X. Jin, M. Iwagami, M. Ishikawa, N. Tamiya, The role of after-hours house- call medical service in the treatment of COVID-19 patients awaiting hospital admission: A retrospective cohort study, Medicine 101 (6) (2022) e28835, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000028835.

G. Alexander, C. Kanth, R. Thomas, A descriptive study on the users and utility of HIV/AIDS helpline in Karnataka, India, Indian J Community Med. 36 (1) (2011) 17–20, https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.80787.

B.S. Chavan, R. Garg, R. Bhargava, Role of 24 hour telephonic helpline in delivery of mental health services, Indian J Med Sci. 66 (5–6) (2012) 116–125.

R. Song, Y.S. Choi, J.Y. Ko, Operating a National Hotline in Korea During the COVID- 19 Pandemic, Osong Public Health Res Perspect 11 (6) (2020) 380–382, https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.6.06.

M. Brülhart, V. Klotzbücher, R. Lalive, S.K. Reich, Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls, Nature 600 (7887) (2021) 121–126, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04099-6.

D. Margolius, M. Hennekes, J. Yao, D. Einstadter, D. Gunzler, N. Chehade, A.R. Sehgal, Y. Tarabichi, A.T. Perzynski, On the Front (Phone) Lines: Results of a COVID-19 Hotline, J Am Board Fam Med. 34 (Suppl) (2021) S95-S102, https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200237.

C. Blake, H. Hadden, M. Dolan, M. Greenwood, M. O’Kane, D. McMahon, A.M. Tobin, Surge in calls to Irish Skin Foundation’s ‘Ask a nurse’ helpline during the COVID-19 pandemic, Clin Exp Dermatol. 46 (7) (2021) 1332, https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.14728.

N. Du, Y. Ouyang, Z. He, J. Huang, D. Zhou, Y. Yuan, Y. Li, M. He, Y. Chen, H. Wang, Y. Yue, M. Xiong, K. Pan, The qualitative analysis of characteristic of callers to a psychological hotline at the early stage of COVID-19 in China, BMC Public Health 21 (1) (2021) 809, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10883-w.

S.A. Elliott, E.S. Bardwell, K. Kamke, T.M. Mullin, K.L. Goodman, Survivors’ Concerns During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Insights From the National Sexual Assault Online Hotline, J Interpers Violence Mar 26 (2022) 8862605221080936, Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221080936.

T. Heimann, O. Berthold, V. Clemens, A. Witt, Fegert JM. Child Abuse and Neglect and the Burden of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Families: A Series of Cases Consulted at the German Medical Child Protection Hotline. Child Abuse Rev. 30 (5) (2021) 485–492, https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2714.

A. Cheng, H. Angier, N. Huguet, D.J. Cohen, K. Strickland, E. Barclay, E. Herman, C. McDougall, F.E. Biagioli, K. Pierce, C. Straub, B. Straub, J. DeVoe, Launching a Statewide COVID-19 Primary Care Hotline and Telemedicine Service, J Am Board Fam Med. 34 (Suppl) (2021) S170-S178, https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200178.

G. Zalsman, Y. Levy, E. Sommerfeld, A. Segal, D. Assa, L. Ben-Dayan, A. Valevski, J.J. Mann, Suicide-related calls to a national crisis chat hotline service during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, J Psychiatr Res. Jul (139) (2021) 193–196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.060.

C. Gerdts, I. Hudaya, Quality of Care in a Safe-Abortion Hotline in Indonesia: Beyond Harm Reduction, Am J Public Health 106 (11) (2016) 2071–2075, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303446.

R. Vonderlin, M. Biermann, M. Konrad, M. Klett, N. Kleindienst, J. Bailer, S. Lis, M. Bohus, Implementierung und Evaluation einer Telefonhotline zur professionellen Ersthilfe bei psychischen Belastungen durch die COVID-19-Pandemie in Baden-Württemberg [Implementation and evaluation of a telephone hotline for professional mental health first aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany], Nervenarzt 93 (1) (2022) 24–33, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-021-01089-x.

L. Zhao, Z. Li, Y. Tong, M. Wu, C. Wang, Y. Wang, N.H. Liu, Comparisons of Characteristics Between Psychological Support Hotline Callers With and Without COVID- 19 Related Psychological Problems in China, Front Psychiatry May 12 (12) (2021) 648974, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.648974.

L. You, X. Jia, Y. Ding, Q. An, B. Li, A Study on the Competence Characteristics of Psychological Hotline Counselors During the Outbreak of COVID-19, Front Psychol. May 7 (12) (2021) 566460, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.566460.

S. Chandrasekaran, V.S. Chandrashekar, S. Dalvie, A. Sinha, The case for the use of telehealth for abortion in India. Sex Reprod Health Matters 29 (2) (2021) 1920566, https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.1920566.

S.A. Clark, C. Davis, R.S. Wightman, C. Wunsch, L.A.J. Keeler, N. Reddy, E.A. Samuels, Using telehealth to improve buprenorphine access during and after COVID-19: A rapid response initiative in Rhode Island, J Subst Abuse Treat. May (124) (2021) 108283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108283.

S.K.B. Hegde, M. Sharma, I. Alam, H.S. Bambrah, A. Deshmukh, D. Varma, Leveraging Health Helplines to Combat COVID-19 Pandemic: A Descriptive Study of Helpline Utilization for COVID-19 in Eight States of India, Asia Pac J Public Health 33 (4) (2021) 441–444, https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395211001173.

N. Petrowski, C. Cappa, A. Pereira, H. Mason, R.A. Daban, Violence against children during COVID-19: Assessing and understanding change in use of helplines, Child Abuse Negl 116 (Pt 2) (2021) 104757, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104757.

A. Anushiravani, H. Vahedi, H. Fakheri, et al., A Supporting System for Management of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease during COVID-19 Outbreak: Iranian Experience-Study Protocol, Middle East J Dig Dis 12 (4) (2020) 238–245, https://doi.org/10.34172/mejdd.2020.188.

K. Kumar, V. Mak, K. Groom, Y. Razak, J.L. Brown, T. Hyde, A. Bokobza, R.K. Coker, M. Parmar, E. Wong, L.Y. Han, S.L. Elkin, Respiratory specialists working in different ways: Development of a GP hotline and respiratory support service during the COVID-19 pandemic, Future Healthc J. 7 (3) (2020) e88-e92, https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0082.

K.L. Rush, L. Howlett, A. Munro, L. Burton, Videoconference compared to telephone in healthcare delivery: a systematic review, Int J Med Inform. Oct (118) (2018) 44–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.07.007.

O. Modgill, G. Patel, D. Akintola, O. Obisesan, H. Tagar, AAA: a rock and a hard place, Br Dent J. 21 (2021)1–5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2594-3.

R. O’Hara, L. Bishop-Edwards, E. Knowles, A. O’Cathain, Variation in the delivery of telephone advice by emergency medical services: a qualitative study in three services, BMJ Qual Saf. 28 (7) (2019) 556–563, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008330.

M.J. Booker, S. Purdy, A.R.G. Shaw, Seeking ambulance treatment for ‘primary care’ problems: a qualitative systematic review of patient, carer and professional perspectives, BMJ Open 7 (8) (2017) e016832, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016832.

K. Eastwood, A. Morgans, K. Smith, J. Stoelwinder, Secondary triage in prehospital emergency ambulance services: a systematic review, Emerg Med J. 32 (2015) 486–92, https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2013-203120.

H. Chaudhry, S. Nadeem, R. Mundi, How Satisfied Are Patients and Surgeons with Telemedicine in Orthopaedic Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Clin Orthop Relat Res. 479 (1) (2021) 47–56, https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000001494.

S. Nourazari, S.R. Davis, R. Granovsky, R. Austin, D.J. Straf, J.W. Joseph, L.D. Sanchez, Decreased hospital admissions through emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic, Am J Emerg Med Apr (42) (2021) 203–210, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.029.

M.M. Jefery, G. D’Onofrio, H. Paek, T.F. Platts-Mills, W.E.III Soares, J.A. Hoppe, N. Genes, B. Nath, E.R. Melnick, Trends in emergency department visits and hospital admissions in health care systems in 5 states in the frst months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, JAMA Intern Med. 180 (10) (2020) 1328–1333, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3288.

National Audit Office. NHS ambulance service. London: National Audit Office, 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all UCC and HMC staff and Departments for their support in running this extensive service during the COVID-19 pandemic, who undertook an excellent task manning the newly introduced service during the pandemic, and have shown commitment, consideration, compassion, and were a great support during this taxing period.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohamed Arafa: study concept, data acquisition, data interpretation, writing the paper, review & editing. Walid El Ansari: data interpretation, writing the paper, review & editing. Fadi Qasem: study concept, data acquisition, data interpretation, editing. Abdulla Al Ansari: study concept, review & editing. Mohammed Al Ateeq Al Dosari: study concept, review & editing.Khalid Mukhtar: study concept, review & editing. Mohamed Ali Alhabash: study concept,review & editing. Khalid Awad: study concept, review & editing. Khalid AlRumaihi: studyconcept, data acquisition, data interpretation, review & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approvaland Consent to Participate

The Institutional Research Board at Hamad Medical Corporation considered this analysis as an audit or service/ therapy evaluation project since the data used were routinely collected for clinical audit and as an integral part of service evaluation purposes. The project was granted exemption from requiring ethical approval (MRC-01-22-384).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arafa, M., El Ansari, W., Qasem, F. et al. Reinventing Patient Support and Continuity of Care Using Innovative Physician-staffed Hotline: More than 60,000 Patients Served Across 15 Medical and Surgical Specialties During the First Wave of COVID-19 Lockdown in Qatar. J Med Syst 47, 77 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-023-01973-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-023-01973-w