Abstract

Introduction

Studies have shown mixed findings regarding the impact of immigration policy changes on immigrants’ utilization of primary care.

Methods

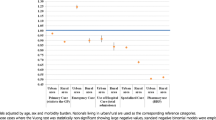

We used a difference-in-differences analysis to compare changes in missed primary care appointments over time across two groups: patients who received care in Spanish, Portuguese, or Haitian Creole, and non-Hispanic, white patients who received care in English.

Results

After adjustment for age, sex, race, insurance, hospital system, and presence of chronic conditions, immigration policy changes were associated with an absolute increase in the missed appointment prevalence of 0.74 percentage points (95% confidence interval: 0.34, 1.15) among Spanish, Portuguese and Haitian-Creole speakers. We estimated that missed appointments due to immigration policy changes resulted in lost revenue of over $185,000.

Conclusions

We conclude that immigration policy changes were associated with a significant increase in missed appointments among patients who receive medical care in languages other than English.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Newkirk B. ‘I can’t imagine the fear.‘ Threat of deportation is keeping patients away from California medical clinics. USA Today, 2017, April 17.

Swetlitz I. Immigrants, fearing Trump’s deportation policies, avoid doctor visits. PBS Newshour, 2017, February 25.

Hoffman J. Sick and Afraid, Some Immigrants Forgo Medical Care. The New York Times; 2017. June 26.

The White House. Executive Order: Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States. Washington, DC: Office of the Press Secretary; 2017.

The White House. Executive Order: Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements, House TW. Editor. 2017: Washington, DC.

The White House, Executive Order: Protecting the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States. 2017: Washington, DC.

Barofsky J, et al. Spreading Fear: The Announcement Of The Public Charge Rule Reduced Enrollment In Child Safety-Net Programs. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1752–61.

Bernstein H, et al. One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018. Editor: U. Institute.; 2019. Urban Institute.

Tolbert J, Artiga S, Pham O, Impact of Shifting Immigration Policy on Medicaid Enrollment and Utilization of Care among Health Center Patients. 2019.

Asch S, et al. Why do symptomatic patients delay obtaining care for tuberculosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(4 Pt 1):1244–8.

Fuentes-Afflick E, Hessol NA. Immigration status and use of health services among Latina women in the San Francisco Bay Area. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(8):1275–80.

Hacker K, et al. The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts. USA Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(4):586–94.

Maldonado CZ, et al. Fear of discovery among Latino immigrants presenting to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(2):155–61.

Ortega AN, et al. Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented Mexicans and other Latinos. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2354–60.

Pulos V, Understanding the ACA in Mass.: Immigrants’ Eligibility for MassHealth & other subsidized coverage, 2015. 2015, Massachusetts Law Reform Institute: Boston.

Yun K, et al. Parental immigration status is associated with children’s health care utilization: findings from the 2003 new immigrant survey of US legal permanent residents. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1913–21.

Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. J Immigr Health. 2001;3(3):151–6.

Hardy LJ, et al. A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1250–4.

Marx JL, et al. The effects of California Proposition 187 on ophthalmology clinic utilization at an inner-city urban hospital. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(5):847–51.

Toomey RB, et al. Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 immigration law on utilization of health care and public assistance among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 1):S28–34.

Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of California’s proposition 187 on the use of primary care clinics. West J Med. 1997;166(1):16–20.

Rhodes SD, et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant hispanics/latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):329–37.

National Immigration Law Center. Trump’s Executive Orders and Immigrants’ Access to Health, Food, and Other Public Programs. Los Angeles; 2017.

McComb S, et al. Cancelled Primary Care Appointments: A Prospective Cohort Study of Diabetic Patients. J Med Syst. 2017;41(4):53.

Nwabuo CC, et al. Factors associated with appointment non-adherence among African-Americans with severe, poorly controlled hypertension. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e103090.

Davies ML, Goffman RM, May JH, et al. Large-Scale No-Show Patterns and Distributions for Clinic Operational Research. Healthcare (Basel), 2016. 4(1):15. Published 2016 Feb 16. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4010015

McMullen MJ, Netland PA. Lead time for appointment and the no-show rate in an ophthalmology clinic. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:513–6.

Samuels RC, et al. Missed Appointments: Factors Contributing to High No-Show Rates in an Urban Pediatrics Primary Care Clinic. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(10):976–82.

Kaplan-Lewis E, Percac-Lima S. No-show to primary care appointments: why patients do not come. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(4):251–5.

Cashman SB, et al. Patient health status and appointment keeping in an urban community health center. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(3):474–88.

Miller AJ, et al. Predictors of repeated “no-showing” to clinic appointments. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36(3):411–4.

Torres O, et al. Risk factor model to predict a missed clinic appointment in an urban, academic, and underserved setting. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18(2):131–6.

Huang YL, Hanauer DA. Time dependent patient no-show predictive modelling development. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29(4):475–88.

Navarro MJ, LaPiene B, Sivak S. Wait Times Less Than 2 Weeks Minimize No-Show Rates in Cardiology Practices. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(6):684. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617706019

Hwang AS, et al. Appointment “no-shows” are an independent predictor of subsequent quality of care and resource utilization outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1426–33.

McGovern CM, et al., A missed primary care appointment correlates with a subsequent emergency department visit among children with asthma. J Asthma, 2017: p. 1–6.

Nuti LA, et al. No-shows to primary care appointments: subsequent acute care utilization among diabetic patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:304.

Schectman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685–7.

Mugavero MJ, et al. Beyond core indicators of retention in HIV care: missed clinic visits are independently associated with all-cause mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):1471–9.

Bundrick Harrison L, Lingvay I. Appointment and medication non-adherence is associated with increased mortality in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. Evid Based Med. 2013;18(3):112–3.

Nwadiuko J, et al. Changes in Health Care Use Among Undocumented Patients, 2014-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210763–3.

Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2401–2.

Hanchate AD, et al. Massachusetts reform and disparities in inpatient care utilization. Med Care. 2012;50(7):569–77.

America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered, ed. M.E. Lewin and S. Altman. 2000, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.302.

Levison J, et al. Development and validation of a computer-based algorithm to identify foreign-born patients with HIV infection from the electronic medical record. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(2):557–70.

Migration Policy Institute. Profile of the Unauthorized Population: Massachusetts. 2015 January 15, 2015 [cited 2017 September 28, 2017]; Available from: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/MA.

Department of Homeland Security, Acting Secretary Elaine Duke Announcement On Temporary Protected Status For Haiti. 2017, November 20: Washington.

Dooling S. Temporary Immigration Status For Nearly 5,000 Haitians In Mass. Will Come To An End. WBUR; 2017. November 21.

Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why We Should Not Be Indifferent to Specification Choices for Difference-in-Differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1211–35.

Mann L, et al. Reducing the Impact of Immigration Enforcement Policies to Ensure the Health of North Carolinians: Statewide Community-Level Recommendations. N C Med J. 2016;77(4):240–6.

Krieger N, et al., Severe sociopolitical stressors and preterm births in New York City: 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2018. 72(12): p. 1147–1152.

Saeed S, et al. Evaluating the impact of health policies: using a difference-in-differences approach. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(4):637–42.

Bassett M, Chen JT, Krieger N, Working Paper Series The unequal toll of COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: Quantifying racial/ethnic disparities. 2020, Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies: Cambridge.

The COVID Tracking Project. 2020 August 3, 2020 [cited 2020 August 3, 2020]; Available from: https://covidtracking.com/data.

Funding

This study was funded by the Cambridge Health Alliance Foundation and the Pisacano Leadership Foundation of the American Board of Family Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jirmanus, L.Z., Ranker, L., Touw, S. et al. Impact of United States 2017 Immigration Policy changes on missed appointments at two Massachusetts Safety-Net Hospitals. J Immigrant Minority Health 24, 807–818 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01341-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01341-9