Abstract

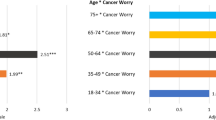

There is a paucity of studies centering on the correlates of cancer worry among Hispanics from the Dominican Republic and the potential informatics strategies to address such worries. Data were analyzed using descriptive and correlational statistics, and logistic regression with the dependent variable of cancer worry. Independent variables for the regression were: age, gender, marital status, education, socioeconomic status, previous diagnosis of cancer, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and chronic burden. Four variables significantly increased cancer worry: married marital status (OR = 1.19 [95% CI 1.01, 1.41]), younger age (OR = .992 [95% CI 0.987, 0.997]), less depression (OR = .96 [95% CI 0.94, 0.98]), and cancer diagnosis (OR = 2.12 [95% CI 1.24, 3.65]). New knowledge was generated on the contextual factors that influence these health concerns in a major Hispanic sub-group. Implications for practice, research and education are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brown A, Patten E. Hispanics of Dominican origin in the United States, 2011. Washington: Pew Charitable Trust. 2013. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/06/19/hispanics-of-dominican-origin-in-the-united-states-2011/. Accessed 13 Apr 2016.

Center for Latrin American, Caribbean and Latino Studies [CLACLS] (2011). The Latino population of New York City, 1990–2010: Latino Data Project—Report 44. The Graduate Center, City University of New York

New York City Department of City Planning: Population facts. http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/data-maps/nyc-population/population-facts.page. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/race-aian.html. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

Pew Research Center. Statistical profile: Hispanics of Dominican origin in the United States, 2011. 2013. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/06/19/Hispanics-of-dominican-origin-in-the-united-states-2011/. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community health profiles: Take care Inwood and Washington Heights. 2006. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2006chp-301.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

Olson EC, et al. Take care inwood and Washington heights. NYC Commu Health Profiles. 2006;19(42):1–16.

Cottler LB, et al. Community needs, concerns, and perceptions about health research: findings from the clinical and translational science award sentinel network. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1685–92.

Lee YJ, et al. Online health information seeking behaviors of Hispanics in New York City: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(7):e176. doi:10.2196/jmir.3499.

Custers JA, et al. The cancer worry scale: detecting fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(1):E44–E50.

Fernández ME, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among Latinos in three communities on the Texas–Mexico border. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(1):16–25.

Janz NK, et al. Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multi-ethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1827–36.

Kelly KM, et al. Cancer recurrence worry, risk perception, and informational-coping styles among Appalachian cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;29(1):1–18.

Breznitz S. A study of worrying. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1971;10:271–9.

Cabrera E, Zabalegui A, Blanco I. Versión española de la Cancer Worry Scale (Escala de Preocupación por el Cáncer: adaptación cultural y análisis de la validez y la fiabilidad). Med Clin. 2011;136(1):8–12.

Lerman C, et al. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychol. 1991;10(4):259–67.

McBride C, et al. Understanding the role of cancer worry in creating a “teachable moment” for multiple risk factor reduction. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:790–800.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psych Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Hay JL, McCaul KD, Magnan RE. Does worry about breast cancer predict screening behaviors? A meta-analysis of the prospective evidence. Prev Med. 2006;42(6):401–8.

Wevers MR, et al. Does rapid genetic counseling and testing in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients cause additional psychosocial distress? Results from a randomized clinical trial. Genet Med. 2015;18(2):137–44. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.50.

Cabrera E, et al. The impact of genetic counseling on knowledge and emotional responses in Spanish population with family history of breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:382–8.

Jandorf L, et al. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among low income immigrant Hispanics. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:462–9.

Quillin J, et al. Genetic risk, perceived risk, and cancer worry in daughters of breast cancer patients. J Genet Couns. 2011;20:157–64.

Flórez K, et al. Fatalism or destiny? A qualitative study and interpretative framework on Dominican women’s breast cancer beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:291–301.

Consedine NS, et al. Fear and loathing in the Caribbean: three studies of fear and cancer screening in Brooklyn’s immigrant Caribbean subpopulations. Infect Agents Cancer. 2009;4 Suppl 1:S1–S4.

Consedine NS, et al. Fear, anxiety, worry, and breast cancer screening behavior: A critical review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13:501–10.

Graves K, et al. Perceived risk of breast cancer among Latinas attending community clinics: risk comprehension and relationship with mammography adherence. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(10):1373–82.

Heckman CJ, Cohen-Filipic J. Brief report: ultraviolet radiation exposure, considering acculturation among Hispanics (project URECAH). J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(2):342–6.

Cella D, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Rosenbaum S. Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:635–40. doi:10.1056/NEJM200202213460825.

Foraker RE, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, Medicaid coverage and medical management of myocardial infarction: atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) community surveillance. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):632. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-632.

Spitzer RL, et al.: Validity and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:1737–44. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Accessed 13 Apr 2016.

Coohey C. The relationship between familism and child maltreatment in Latino and Anglo families. Child Maltreat. 2001;6(2):130–42.

Contreras JM, et al. Parent–child interaction among Latina adolescent mothers: the role of family and social support. J Res Adolesc. 1999;9:417–39.

Sue DW, Sue D. Counseling the culturally diverse: theory and practice. New York: Wiley; 2003.

Bennett P, et al. Concerns and coping during cancer genetic risk assessment. Psychooncology. 2012;21(6):611–7.

Borreani C, et al. The psychological impact of breast and ovarian cancer preventive options in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Clin Genet. 2014;85(1):7–15.

Lillie AK, Clifford C, Metcalfe A. Caring for families with a family history of cancer: why concerns about genetic predisposition are missing from the palliative agenda. Palliat Med. 2011;25:117–24.

Mellon S, et al. Risk perception and cancer worries in families at increased risk of familial breast/ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(8):756–66.

Phillips KM, et al. Factors associated with breast cancer worry 3 years after completion of adjuvant treatment. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):936–9.

Vadaparampil ST, McIntyre J, Quinn GP. Awareness, perceptions, and provider recommendation related to genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer risk among at-risk Hispanic women: similarities and variations by sub-ethnicity. J Genet Couns. 2010;19(6):618–29.

Ruiz PM. Dominican concepts of health and illness. J N. Y. Nurses Assoc. 1990; 21(4):11–13.

Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington: National Academies Press; 2010.

Institute of Medicine. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington: National Academies Press; 2013.

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer. 2014. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003090-pdf.pdf. Accessed 13 Apr 2016.

Pacsi A. Understanding the experience of Dominican American women with late stage breast cancer: A qualitative study. Hisp Health Care Int. 2015;13(2):86–96.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the women who participated in this study. This research was supported by Reducing Health Disparities through Informatics (T32NR007969, Suzanne Bakken, principal investigator).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sepulveda-Pacsi, A.L., Bakken, S. Correlates of Dominicans’ Identification of Cancer as a Worrisome Health Problem. J Immigrant Minority Health 19, 1227–1234 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0509-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0509-9