Abstract

We examine trends in the Hispanic longevity advantage between 1990 and 2010, focusing on the contribution of cigarette smoking. We calculate life expectancy at age 50 for Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites between 1990 and 2010. We use an indirect method to calculate the contribution of smoking to changes over time in life expectancy. Among women, the Hispanic advantage in life expectancy grows from 2.14 years in 1990 (95 % CI 1.99–2.30 years) to 3.53 years in 2010 (3.42–3.64 years). More than 40 % of this increase reflects widening differences in smoking-attributable mortality. The advantage for Hispanic men increases from 2.27 years (2.14–2.41 years) to 2.91 years (2.81–3.01 years), although smoking makes only a small contribution. Despite persistent disadvantage, US Hispanics have increased their longevity advantage over non-Hispanic whites since 1990, much of which reflects the continuing importance of cigarette smoking to the Hispanic advantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41(3):385–415.

Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Amir SH, Forbes D, Frisbie WP. Adult mortality differentials among Hispanic subgroups and non-Hispanic whites. Soc Sci Q. 2000;81(1):459–76.

Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic mortality paradox: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e52–60. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.30110.

Singh GK, Siahpush M. Ethnic-immigrant differentials in health behaviors, morbidity, and cause-specific mortality in the United States: an analysis of two national data bases. Hum Biol. 2002;74(1):83–109.

Elo IT, Turra CM, Kestenbaum B, Ferguson BR. Mortality among elderly Hispanics in the United States: past evidence and new results. Demography. 2004;41(1):109–28.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–8.

Arias E. United States life tables by hispanic origin. Vital Health Stat. 2010; 152(2).

Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol Ser B-Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:68–75.

Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic Status in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;270(20):2464–8.

Sorlie PD, Rogot E, Johnson NJ. Validity of demographic characteristics on the death certificate. Epidemiology. 1992;3(2):181–4.

McKenney NR, Bennett CE. Issues regarding data on race and ethnicity: the Census Bureau experience. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(1):16–25.

Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat. 2008;148:1–23.

Lariscy JT, Hummer RA, Rath JM, Villanti AC, Hayward MD, Vallone DM. Race/ethnicity, nativity, and tobacco use among US young adults: results from a Nationally Representative Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;20:1417. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts344.

Bethel JW, Schenker MB. Acculturation and smoking patterns among Hispanics: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):143–8.

Blue L, Fenelon A. Explaining low mortality among US immigrants relative to native-born Americans: the role of smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):786–93.

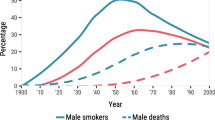

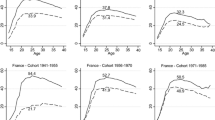

Fenelon A. Revisiting the Hispanic mortality advantage in the United States: the role of smoking. Soc Sci Med. 2013;82:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.028.

Denney JT, Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Pampel FC. Education inequality in mortality: the age and gender specific mediating effects of cigarette smoking. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39(4):662–73. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.02.007.

Forey BA, Hamling J, Lee P, Wald N. International smoking statistics: a collection of historical data from 30 economically developed countries. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Burns DM, Lee, L, Shen LZ, et al. Cigarette Smoking Behavior in the United States. In: Changes in cigarette-related disease risks and their implications for prevention and control, smoking and tobacco control. Smoking and tobacco control monograph no. 8, NIH publication no. 97-4213. Bethesda, MD: Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health; 1997:13–112.

Preston SH, Glei DA, Wilmoth JR. A new method for estimating smoking-attributable mortality in high-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):430–8.

Haldorsen T, Grimsrud TK. Cohort analysis of cigarette smoking and lung cancer incidence among Norwegian women. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(6):1032–6.

Brennan P, Bray I. Recent trends and future directions for lung cancer mortality in Europe. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(1):43–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600352.

Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):903–19. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl089.

Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun MJ. Mortality From Smoking in Developed Countries 1950−2000, 2nd Edition. 2006. Available at: http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/deathsfromsmoking.

Preston SH, Wang HD. Sex mortality differences in the United States: the role of cohort smoking patterns. Demography. 2006;43(4):631–46.

Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the US: the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2023–34.

Flegal KMCM. Prevalence and trends in obesity among us adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.2014.

Martin LG, Soldo BJ. Population NRC (US) C on. National Academies: Racial and ethnic differences in the health of older Americans; 1997.

Saydah S, Lochner K. Socioeconomic status and risk of diabetes-related mortality in the US. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(3):377–88.

U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009; 2010.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Measuring the accumulated hazards of smoking: global and regional estimates for 2000. Tob Control. 2003;12(1):79–85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

IRB statement: the study received no IRB review since the research does not constitute human subjects research.

Appendix

Appendix

Our primary methodological concern is the accurate assessment of Hispanic origin in vital statistics and the US census. That is, research on the Hispanic paradox indicates that one of the early challenges of producing estimates of life expectancy among US Hispanics was obtaining consistent measurements of Hispanic ethnicity between the data sources used for death rate numerators and death rate denominators [5]. Any mismatch in Hispanic ethnicity coding may lead to biased estimates of Hispanic mortality, and thus of the magnitude of the Hispanic longevity advantage [12].

This bias has been shown to be small in recent years [7]. However, it may not have been small in 1990, the first year of analysis in this study. US vital statistics data from 1990 contain a large number of death certificates on which Hispanic origin is recorded as “unclassifiable.” Roughly 90,000 individuals aged 50 and above have no available information on Hispanic origin that year, representing nearly 5 % of deaths in this age group. Therefore, to examine the sensitivity of our results to assumptions about unclassifiable individuals, we present a series of counterfactual scenarios in which various proportions of the unclassifiable group are assumed to be Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, or non-Hispanic other.

Figure 3 presents the results of our sensitivity analysis. It shows the magnitude of the Hispanic longevity advantage in four scenarios:

Sensitivity and robustness: Hispanic life expectancy advantage at age 50 in 1990, calculated under four different assumptions regarding the Hispanic ethnicity of “unclassifiable” deaths in the 1990 multiple cause of death files. “Hispanic advantage” is defined as the difference, in years, between life expectancy at age 50 among Hispanics and life expectancy at age 50 among non-Hispanic whites. Baseline scenario assumes unclassified deaths have the same racial/ethnic distribution as classified deaths; High scenario assumes 90 % of unclassified deaths are non-Hispanic white, 9 % are other, and 1 % are Hispanic; medium scenario assumes that 75 % are non-Hispanic white, 20 % are other, and 5 % are Hispanic; low scenario assumes That 75 % are non-Hispanic white, 15 % are other, and 10 % are Hispanic

-

1.

the baseline scenario—that used for the primary analysis in the paper—assumes that unclassifiable deaths have the same racial/ethnic distribution as classifiable deaths;

-

2.

the High scenario assumes 90 % of unclassified deaths are non-Hispanic white, 9 % are other, and 1 % are Hispanic;

-

3.

the Medium scenario assumes that 75 % are non-Hispanic white, 20 % are other, and 5 % are Hispanic; and

-

4.

the Low scenario assumes that 75 % are non-Hispanic white, 15 % are other, and 10 % are Hispanic.

The proportions attributed to each group are ultimately arbitrary. However, we consider it unlikely for more than 10 % of the 1990 unclassifiable deaths to be among Hispanics, or for more than 90 % to be among non-Hispanic whites. In almost all age groups 50 and above, 2–5 % of classifiable decedents are Hispanic, and 75–90 % are non-Hispanic white. Furthermore, the total number of the unclassifiable deaths is large enough—much larger than the total number of deaths classified as Hispanic—that attributing a proportion substantially greater than 10 % to Hispanics would result in implausibly low life expectancy among this group [7]. Attributing more than 90 % to non-Hispanic whites is inconsistent with reported race among those with unclassifiable Hispanic ethnicity; that is, nearly 20 % of those with unclassifiable Hispanic ethnicity are reported as non-white.

Figure 3 shows that our assumption regarding the racial/ethnic distribution of “unclassifiable” deaths has a considerable influence on our estimate of the magnitude of the Hispanic longevity advantage. This is consistent with previous research [8]. However, despite uncertainty over the precise magnitude of the Hispanic advantage in 1990, it is almost certain that the advantage has grown over the period 1990–2010. In each sensitivity analysis scenario, the estimated Hispanic advantage for women is markedly lower than that observed in the year 2000 (3.03 years); for men, the estimated advantage is lower than in 2000 (2.47 years) in each scenario except the High, where it is 2.62 years. This High scenario, it is worth noting, assumes that almost no deaths with unclassifiable ethnicity occurred among Hispanics (just 1 %). Moreover, the greater the proportion of unclassifiable deaths assumed to occur among Hispanics, the more striking the improvement in Hispanic advantage appears. Thus, although there is a great deal of uncertainty in our estimation of the 1990 Hispanic advantage, the sensitivity analysis supports our conclusion that the increase in the advantage over time represents a real trend.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fenelon, A., Blue, L. Widening Life Expectancy Advantage of Hispanics in the United States: 1990–2010. J Immigrant Minority Health 17, 1130–1137 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0043-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0043-6