Abstract

Vegetarianism improves human and planetary health in addition to animal welfare. Motivations for meat-reduced diets include health-related and ethical reasons, with the latter being the main driver for eschewing meat. However, evidence on vegetarian happiness is inconclusive and the results reported are mixed. This constitutes a challenge for policy aiming to encourage people to shift toward plant-based diets. In this research, we aim to provide some evidence on this question: to what extent is there a link between the different moral codes related to ideas of happiness and vegetarianism? To do so, we apply the happiness moral codes from the Conceptual Referent Theory, and assess vegetarianism from the perspective of the psychological aspect of vegetarian identity (flexitarian, pescatarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian, and vegan) and dietary behavior (vegetarian self-assessment scale). Analyzing a sample of university students in Spain, we discover that some happiness constructs (tranquility, fulfilment, and virtue) are positively related to vegetarianism while others are inversely related (enjoyment and stoicism). In terms of policy implications, we find that ethical grounds one holds on happiness in relation to vegetarianism may play a role in fostering or hindering plant-based lifestyles.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Vegetarianism is a plant-based dietary lifestyle that involves eschewing meat to avoid doing harm. Compared to mainstream omnivorism, it delivers numerous benefits at the individual and collective levels (Fox & Ward, 2008; Ruby, 2012). A balanced vegetarian diet brings physical health and vitality on the one hand, while on the other it actively contributes to preserving biodiversity richness and reducing CO2 emissions (Campbell, 2004; Stoll-Kleemann & Schmidt, 2017). Vegetarianism helps ensure other, nonhuman beings and future generations of living beings enjoy good living conditions, thus linking to moral aspects of human behavior and creating more compassionate societies (Rosenfeld & Burrow, 2017; Leite et al., 2019).

Given that vegetarianism promotes human health and animal welfare, as well as creates better environmental conditions for present and future generations, it seems reasonable in moral terms to propose the worldwide adoption of a vegetarian diet as a replacement for the omnivorous diet. Encouraging the spread of vegetarianism would be easier if it was shown to also help generate immediate happiness, and if the causes that trigger people to adopt vegetarianism were better understood. Subjective well-being, also termed happiness, refers to individual facets of being well, such as life satisfaction and emotional experiences (Geerling & Diener, 2018). Yet mixed findings on happiness and vegetarianism have been reported (Blanchflower et al., 2013; Dobersek et al., 2021; Forestell & Nezlek, 2018; Iguacel et al., 2020; Krizanova & Guardiola, 2020; Lindeman, 2002). Some research emphasizes the positive link between vegetarianism and subjective well-being, from the concept of plant-based diets increasing life satisfaction, health, vitality, and flourishing (Conner et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2020; Mujcic & Oswald, 2016). When exploring the link beyond simply eating vegetarian food, internalization of the vegetarian identity is found to be crucial for personal expression (Beardsworth & Keil, 1992; Rosenfeld & Burrow, 2017) since it channels ethical, ecological, and health commitments (Schenk et al., 2018). In this vein, the vegetarian self-identity has a link with subjective well-being, although it is not straightforward. Some literature argues that people who identify as vegetarians are happier than omnivores (Agarwal et al., 2015; Beezhold & Johnston, 2012). However, most findings support a negative link between vegetarian identity and subjective well-being, leading to increased anxiety, depression, and reduced life satisfaction levels (Dobersek et al., 2021; Forestell & Nezlek, 2018; Remick et al., 2009). These substantial efforts to understand happiness and vegetarianism in both of its dimensions—self-identity and dietary behavior—have yielded inconclusive results, which constitutes a challenge when it comes to encouraging responsible lifestyles among a wider public.

Less attention has been devoted to analyzing people’s moral ideologies underlying their efforts to lead happy lives when committing to sustainable dietary behavior. Motivational drivers of vegetarianism relate to concern for animals, health, the environment, and spirituality, with concerns about animal welfare being the most common cause (Rosenfeld, 2019; Ruby, 2012). Research on vegetarianism and morality highlights the role of the ideological basis for motivations for vegetarianism and consequent dietary behavior (Rosenfeld, 2019; Ruby, 2012). Indeed, it is the ethical motivation of nonhuman well-being that ignites the vegetarian moralization process (Devine, 1978). As a result, the vegetarian choice is highly reflexive and mirrors the individual’s life philosophy (Beardsworth & Keil, 1992; Fox & Ward, 2008; Lindeman & Sirelius, 2001), as well as helping people gain an understanding of the self and the world around them (Lindeman & Stark, 1999).

In our prior work on vegetarian happiness, we used data collected from the same sample but focused on different variables such as hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in relation to nature connectedness (Krizanova & Guardiola, 2020). In this research we incorporate the line of vegetarianism and the morality of happiness in order to address the following question: to what extent is there a link between different moral codes related to happiness ideas and vegetarianism? To our knowledge, there is no evidence to date on the link between different moralities concerning how people try to achieve a happy life and vegetarianism. Consequently, in this research we seek to shed some light on this knowledge gap and unveil further aspects of the complexity of happiness for vegetarians. To achieve this, we employ the Conceptual Referent Theory (CRT) developed by Mariano Rojas (2005). This theory posits the importance of the cognitive process involved in what people think of the idea of being well. The CRT proposes eight different moral conceptions, namely stoicism, virtue, utopian, tranquility, fulfilment, satisfaction, carpe diem, and enjoyment. We aim to relate this theory to vegetarianism, assessed in terms of the vegetarian identity and vegetarian dietary scale. To do so, we use a sample of 966 university students from Granada, Spain. From a political perspective, the ideal would be to identify conceptualizations of happiness that foster and hinder vegetarianism, in order to cultivate the former while discouraging the latter. In this regard, we assume that the best political option is to support a dietary shift for individual well-being and environmental benefits by eating less meat.

To address our research question, the rest of the paper is structured as follows: In Sect. 2, we present the vegetarianism and morality literature (2.1) and the CRT (2.2) in greater detail. In Sect. 3, we introduce the sample and the variables, as well as the analysis techniques. The results are detailed in Sect. 4, while in Sect. 5 we discuss their political implications, the limitations of the study, and propose further research. Finally, in Sect. 6 we conclude.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Vegetarianism and Morality

As a framework for our research, we approach the concept of morality through the lens of the main motivational causes leading to vegetarianism, since different food choice motives reflect individuals’ different ideological foundations shaping their dietary decisions (Lindeman & Sirelius, 2001). Many scholars conclude that there are two primary motivations for the vegetarian choice: health and ethics. They constitute a common taxonomic model employed in qualitative (Beardsworth & Keil, 1992; Fox & Ward, 2008; Jabs et al., 1998; Janda & Trocchia, 2001) and quantitative studies on vegetarianism (Hoffman et al., 2013; Radnitz et al., 2015), as well as in theoretical frameworks (Ruby, 2012; Rosenfeld & Ruby, 2017). Health-oriented vegetarians are individuals who decide to avoid meat for their own health and well-being (Ruby, 2012). Evidence on this perspective suggests that a balanced vegetarian diet may contribute to optimal health and reduce some of the risks of heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and some cancers (Melina et al., 2016; Yokoyama et al., 2014). The second widespread motivation for becoming vegetarian is related to the ethics, acting out of concern for animal, environmental, spiritual, and human welfare, which are generally interlinked rather than operating separately. The different motivations for a meatless diet tend to intertwine throughout the life of vegetarians thus ensuring dietary consistency and a commitment to eschewing meat (Beardsworth & Keil, 1992; Fox & Ward, 2008; Ruby, 2012, Rosenfeld & Ruby 2017). For instance, a study conducted in the UK reports that within the sample of vegetarian participants, 74% had changed their motives for being vegetarian; 34% had added a motive, 13% had abandoned a motive, and 23% had both included new motivations and discontinued original causes (Hamilton, 2006).

2.1.1 Moral Differences Between Health and Ethical Vegetarians

Evidence suggests that it is the ethical vegetarian who embodies the moralization process triggered by an inherent concern for animal welfare (Devine, 1978; Jabs et al., 1998; Ruby, 2012). For example, a qualitative study conducted in the US analyzed 47 participants who had been vegetarians for a period of between 3 and 56 years. They found differences between health and ethical vegetarians as regards disgust-related reactions to meat such as anxiety, guilt, unease or sickness and concluded that these reactions were present exclusively among ethically-oriented vegetarians while none of the health-oriented vegetarians reported such reactions (Hamilton, 2006). In this vein, Lindeman and Sirelius (2001) conducted a quantitative study and analyzed a sample of 232 Finnish female students, suggesting that health and ethical vegetarians differ in their ideological foundations. They conclude that ethical vegetarians are more driven by humanistic values while health vegetarians are more motivated by concerns linked to personal safety and security (Lindeman & Sirelius, 2001; Ruby, 2012). Similarly, a qualitative study by Fox and Ward (2008) conducted with 33 participants, mainly from the US, Canada, and the UK, indicates that health vegetarians are more centered on the effects of a vegetarian diet on individual health, with ethical vegetarians being more connected to motivations within a philosophical, ideological, or spiritual context (Fox & Ward, 2008).

2.1.2 The Moralization Process of the Ethical Vegetarian and Happiness

Ethical vegetarians are mainly driven by moral considerations (Jabs et al., 1998; Ruby, 2012). The moral values a person cultivates often refer to an internalized concept that is part of the self (Rozin et al., 1997). Given ethical vegetarians’ strong concern about the morality of their actions, they commonly develop disgust towards meat (Rothgerber, 2017; Rozin et al., 1997), which makes the ethical motivation the predominant reason for vegetarian lifestyles. This claim is supported by results from a qualitative study of 20 vegetarians (Romo & Donovan-Kicken, 2012) and a quantitative study of 35 vegans, 111 vegetarians, 75 semi-vegetarians, and 265 non-vegetarians (Timko et al., 2012). In addition, the factor of speciesism, which refers to moral differences between different species of animals, has been highlighted in a study of 576 participants in the US relating ethical dietary motivations and vegetarian identity (Rosenfeld, 2019). Accordingly, the reason why vegans are more ethically oriented may be due to the fact that vegans reject speciesism more strongly than vegetarians do. By opposing speciesism, vegetarians express their beliefs that humans should not have a higher moral status than animals (Caviola et al., 2019). These findings suggest that taking into account not only the dietary motivations but also the ideological foundations for people’s food choices might be useful when attempting to promote ethical vegetarianism (Rosenfeld, 2019).

Historically, the archetypal moral vegetarian has been seen as a radical or independent thinker who disapproves of violence, war, and oppression (Shapin, 2007), and is also associated with more liberal and altruistic values involving pro-environmental and pro-social behavior, social justice, and equality; in contrast with omnivores being in favor of more traditional values related to obedience, family, and social order (Ruby, 2012). Many vegetarians, particularly females, view the world as unfair to other living beings (Lindeman, 2002; Rosenfeld, 2018) and opt for pro-social behavior as a way of life (Jabs et al., 2000). Regarding moral motivations for consciously reducing meat intake, it is also worth mentioning the flexible meat-reducer identity—the flexitarian—who engages in part-time vegetarianism in order to diminish the environmental pressures of animal husbandry (De Groeve et al., 2021; Raphaely & Marinova, 2014). However, evidence suggests certain differences between vegetarian and flexitarian profiles, with the latter being less likely than full-time vegetarians to exhibit dietary motivations associated with animal and environmental welfare (De Backer & Hudders, 2015). These nuances are to be expected given the distinctions identified in terms of philosophical, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics between meat reducers and omnivores (Janda & Trocchia, 2001; Schenk et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, the main feature of ethical vegetarianism is the development of the personal ideology concerning the consumption of other, nonhuman beings. It is when suffering is being inflicted on others that people are inclined to reflect on their actions and behavior (Devine, 1978). Consequently, the morality of vegetarianism centers on the unnecessary suffering of others that could be avoided with an alternative solution of plant-based diets that are beneficial for human and planetary health (Deckers, 2009). Furthermore, at the policy level, the ethics of not eating meat might be more effective in encouraging a dietary shift compared to health motivations (Ogden et al., 2007). That said, there is fairly scarce evidence relating different moral aspects of people’s happiness and the decision to be a vegetarian. The empirical research on the topic has focused on food choice motives and abstract values in relation to food choice ideologies, and how these reflect the normativism–humanism polarity (Lindeman & Sirelius, 2001). There is some more evidence concerning the connection between being vegetarian and the experience of being well. Prior research on this subject has primarily centered on subjective well-being measures (Dobersek et al., 2021; Krizanova & Guardiola, 2020), personality traits and happiness (Aslanifar et al., 2014), or happiness and the relationship with food practice (Bertella, 2020; Twine, 2014). However, as far as the authors are aware, no research to date has addressed vegetarians’ philosophical evaluations of happiness. This is the main innovation of this research.

2.2 The Conceptual Referent Theory (CRT)

In order to assess the connection between vegetarianism and ethical conceptions of a happy life, we employ the Conceptual Referent Theory (CRT).

2.2.1 The Theory

The CRT, developed by Mariano Rojas (2005; 2007), holds that people have different conceptual referents or ideas of what a happy life is, and that each referent plays a role in people’s assessment of their life and in their happiness evaluation. It places importance on what individuals think about what a happy life is, rather than what they feel. The CRT consists of a classification based on a review of philosophical thought, with focus groups consulted in order to make this thought accessible to lay people (Rodríguez, 2001). These happiness concepts are labeled stoicism, virtue, utopian, tranquility, fulfilment, satisfaction, carpe diem, and enjoyment (see Fig. 1). The first four conceptions are considered to have an inner orientation, that is, the individual’s ultimate goal in life is based on an unselfish motivation, more closely related to the internal issues affecting each person than to external circumstances. Conversely, the last four are more outer oriented, meaning that they are more conditioned by the external world (Rojas, 2007).

The eight categories can be defined as follows: (1) stoicism is represented by the statement “Happiness is accepting things as they are” and implies a sense of contentment with what happens in life, but could also imply acceptance, austerity and resignation. (2) Happiness as virtue is identified with the sentence “Happiness is a sense of acting properly in our relations with others and with ourselves”. (3) The utopian construct is reflected in the sentence “Happiness is an unreachable ideal we can only try to approach”. It reflects the idea of pursuing certain goals that are unreachable but still drive people’s desires and actions. (4) Happiness as tranquility is reflected in the statement “Happiness is in living a tranquil life, not looking beyond what is attainable”. It is linked to actions driven by prudence and moderation, and the absence of worries and wants.Footnote 1

The constructs described above are related to inner ideas of happiness and goals that depend more on the self than on what happens outside, albeit to different degrees. The following constructs are more related to outer influences: (5) the fulfillment classification refers to the Aristotelian idea of happiness as developing human potential, and is represented by the sentence: “Happiness is in fully exercising our capabilities”. (6) Happiness as satisfaction reflects a rather modern idea of happiness, that is, the cognitive evaluation of one’s life. “Happiness is being satisfied with what I have and what I am” is the statement that reflects this school of thought, associated with social scientists such as Argyle and Veenhoven. (7) The carpe diem idea is in line with the thought of Erasmus regarding living in the present. The statement capturing this conception is “Happiness is to seize every moment in life”. Finally, (8) happiness as enjoyment, closely related to utilitarian thought and authors such as Bentham and Mill, concerns pleasure and the absence of pain. The associated statement is “Happiness is to enjoy what one has attained in life”.

2.2.2 Previous Empirical Evidence on the CRT

There are some prior empirical applications of the CRT, where it is normally used to gain a better understanding of happiness (Rojas, 2005, 2007; Rojas & Vittersø, 2010; Pena-López et al., 2021). Those studies share common ground but also present certain divergent outcomes. The most important results are the following:

-

(i)

There is heterogeneity in the thoughts about what happiness is, which means that people hold different conceptions of happiness. Moreover, those conceptions change from one culture or another; that is, there is not a single construct that is universally preferred. For example, one study (Rojas & Vittersø, 2010) attempted to replicate the findings in different cultures using data from Cuba, Norway, and South Africa, concluding that there are cross-cultural differences in the preferences towards different conceptions.

-

(ii)

Research has also shown that different happiness constructs are dependent on different socioeconomic variables to different extents in different cultures. For instance, using a sample from Mexico, Rojas (2007) demonstrated that income may be an important variable for some constructs but irrelevant for others. In addition, Rojas and Vittersø (2010) found heterogeneity in the relationship of the CRT constructs with gender, age, and education across three chosen cultures.

-

(iii)

The application of the CRT can enable an analysis of whether some constructs are superior or inferior when it comes to enhancing happiness, which may be useful for policy purposes. However, it is again worth noting that there is not a universal pattern; rather, we see cultural differences. For instance, in his early study, Rojas (2005) showed that there are no superior constructs, but there are constructs that negatively relate with life satisfaction, namely utopian, carpe diem, and to some extent fulfilment. On the contrary, another analysis focusing on Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, and the US identified certain constructs as being superior in terms of greater happiness; namely, stoicism, enjoyment, and virtue (Pena-López et al., 2021).

To the authors’ knowledge, no attempts have been made to test how the above happiness constructs may relate to choices that generate positive externalities, such as pro-social or pro-environmental behavior. There is, however, evidence from Spain about how the relationship between pro-environmental behavior and life satisfaction is conditioned by CRT constructs (Binder et al., 2020). The results show certain heterogeneity, indicating that people who report having a stoicism concept of happiness are associated with lower happiness when doing nothing for the environment. On the other hand, fulfillment and tranquility are associated with higher life satisfaction when being environmentally unfriendly.

Understanding the associations between the constructs of happiness and vegetarianism could further our understanding of the role individual moral codes play in sustainable food choices. Therefore, we hypothesize that different moralities concerning how people aim to achieve a happy life may influence the decision of whether or not to be a vegetarian. Using data from a student sample comprised of overall educated individuals, we intend to evaluate the link between vegetarian identity (flexitarian, pescatarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian, and vegan) and dietary pattern (vegetarian self-assessment scale) and the conceptualizations of happiness. A broader aim of this work is to identify new strategies to ensure policy outcomes that are simultaneously beneficial for both human happiness and social and environmental welfare.

3 Methodology

3.1 Participants and Procedure

The participants in our study came from the academic disciplines of economics, pedagogy, social work, politics, sociology, engineering, medicine, information technology, and environmental studies at the University of Granada in Spain. We collected data during the two-month period of March and April 2019, which yielded a total of 1283 records. We conducted an online questionnaire in Spanish via Qualtrics software in the classroom environment of the participants. Students read the survey guidelines, data protection policy, and anonymity conditions before completing it, which took approximately 20 min via smartphone or personal laptop. No monetary or academic compensation was given for participation. This research followed the ethical protocols specified by the University of Granada (Vice-Rectorate for Research & Knowledge Transfer, 2020). We removed missing values and unintelligible observations from the sample, to create a new database for our study comprised of 966 observations.

3.2 Measures

As dependent variables in our analyses we included the eight philosophical conceptualizations of happiness drawn from the CRT (Rojas, 2005). Participants indicated their agreement with these conceptualizations on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Table 1 summarizes the statements for each construct, which have been explained in greater detail in the previous section.

The independent variables of this study relate to vegetarianism, assessed as vegetarian identity and scale, reflecting the individual’s internalization of status aspects of vegetarianism and the person’s dietary behavior, respectively, and a set of socioeconomic variables.

To measure vegetarian identity, we asked participants to self-identify with one of the food identities in relation to their diet: “Please select the option that best describes your diet.” The answer options were omnivore, organic omnivore, flexitarian, pescatarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian, and vegan. Each dietary identity was explained with a short description: a. Omnivore: eats meat and its derivatives, fish and seafood, as well as fruit, vegetables, and cereals. b. Organic omnivore: buys organic meat. c. Flexitarian: does not eat meat at least once a week, that is flexitarians have at least one vegetarian day a week. d. Pescatarian: eats dairy products, fish and seafood, but does not eat meat. e. Lacto-ovo vegetarian: eats eggs and dairy products but does not eat fish, seafood, white or red meats. f. Vegan: eats fruits, vegetables, legumes and cereals but does not eat red or white meats, dairy products, eggs, seafood, and fish. This approach is in line with previously established measures (Allen et al., 2000; Lea et al., 2006), to which we added the food identities “organic omnivore” (quality meat reducer) and “flexitarian” (quantity meat reducer) to gain broader coverage of common food identities in Spain.

For the vegetarian self-assessment scale, we asked participants about their dietary behavior (vegetscale). We employed the 10-point dietary preference scale before addressing their identification as a vegetarian: “Please indicate your eating habits on the scale from 1 to 10, from omnivorous to vegan, where 1 means being completely omnivorous (eating all products of animal origin) and 10 completely vegan (eating no products of animal origin)” (Lea et al., 2006).

We included a set of socioeconomic variables that act as control variables; namely income, age, gender, and civil status. Given that the sample is comprised of students, we considered the parents’ income, for which we specified eight intervals. The minimum was established at less than €499 and the maximum at €5000 or more. We calculated the income using the midpoint of the interval (except for the maximum, which was estimated at €6000). Income per capita was obtained by dividing the value by the number of people living in the household. We employed the natural logarithm of these incomes. We accounted for the age of participants in years. We asked about the gender (male, female, or other) and also considered a dummy variable that equaled one if the respondent is single, as a proxy of civil status.

Finally, we included some motivational variables for the subset of flexitarians, vegetarians, and vegans (N = 204). As the analyses were run on vegetarian and nonvegetarian profiles, those variables are used for descriptive purposes. Respondents had to choose several options from a question concerning why they do not eat meat, specifically “why did you choose to follow this diet?”. We classified the responses into three categories: health, ethics, and others. The health category indicates whether the participants are motivated to follow the meat-reduced diet in order to improve their own health (3 possible options in total, e.g. “I follow this diet for health reasons,” “I follow this diet for weight control”). The category of ethics includes motives linked to concern for the environment, animals, spirituality, and social activism (6 possible options in total, e.g. “I follow this diet because of animals rights,” “I follow this diet for the environment,” “I follow this diet to reduce world hunger") while the remaining motivational category entails social, economic, and taste drivers (6 possible options in total, e.g. “I follow this diet for my family,” I follow this diet because it is cheaper than the omnivorous one,” I follow this diet because I do not like the taste of meat”).

3.3 Method of Analysis

To examine the relationship between conceptualizations of happiness and vegetarianism, we use a regression analysis. We estimate a different model for each happiness construct, as well as for the vegetarian identity and vegetarian self-assessment scale. Therefore, the estimations to perform follow those specifications:

We run eight models for each equation, one for each happiness conceptualization (j = 8). In Eq. 1 we incorporate the different vegetarian identities (m = 6) as dummy variables, leaving omnivore as the omitted dummy. In Eq. 2 we consider eight models for the vegetarian scale. For the estimation of the parameters, we use Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). Given that happiness conceptualization is an ordinal variable, it would be more appropriate to use an ordered probit model for this variable. However, we apply OLS because of its ease of interpretation and because the results from the two methods are very similar (Ferrer-i-Carbonell & Frijters, 2004). Furthermore, to reinforce the evidence, we redo the analyses referring to happiness conceptualization using ordered probit models, arriving at similar results and conclusions. These results are not included in the paper but are easily replicable using the supplementary material. Data analysis is performed using Stata statistical software.

4 Results, Discussion, and Policy Implications

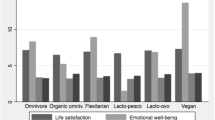

Before presenting the estimations, we provide in Table 2 several descriptive statistics. Concerning the philosophical happiness constructs, the results indicate that the lowest mean is for stoicism, while the highest are for satisfaction and enjoyment, which have an outer orientation. In addition, the four outer orientation constructs are the ones with the lowest standard deviation.

The most frequent dietary identity is omnivore, representing slightly more than three quarters of the sample. The next most frequent dietary identity, related to meat avoidance, is flexitarian (12.6%), followed by vegetarians at 8.5% (2.9% pescatarians, 4.6% lacto-ovo vegetarians, and 1% vegans). Concerning vegetarianism, the vegetarian scale has a value of 3.5, which reflects the dietary habits of the omnivore majority in the sample.

The socioeconomic control variables indicate that more than half of the sample (62.4%) are women and around a third of the sample has a partner. The age ranges from 18 to 54 years old, including lifelong learners, with a mean of 21 years old (SD = 2.8). People aged 30 or over represent 1.1% of the sample.

Before presenting the regression analyses, we take a closer look at the meat-reducer subsample, comprising 204 individuals in Table 3. To do so, we include a set of key variables, as well as the motivation variables, and implement a simple pairwise Pearson correlation. The CRT variables are positively related to each other to some extent. The vegetarian scale is positively related to tranquility and negatively related to stoicism and enjoyment (a closer look with more sophisticated techniques allows us to reassess those results in Sect. 4.2). More interestingly, the variables related to motivations are somewhat linked to the vegetarian scale and the CRT variables. Health-motivated vegetarians are positively related to fulfillment, while other motivations are associated with satisfaction and enjoyment. Ethical vegetarians seem not to be related to any CRT variables, but they tend to score high on average for the vegetarian scale.

4.1 The Relationship Between Conceptualizations of Happiness and Vegetarian Identity

The results of the estimations for vegetarian identity are displayed in Table 4. All happiness constructs are related to different vegetarian identities to some extent, except carpe diem. Stoicism is negatively related to several identities, namely flexitarian and lacto-ovo vegetarian, while enjoyment is negatively related to lacto-ovo vegetarian. Another negative relationship is found in model 3, as ranking high in the utopian construct is negatively related to self-identification as a vegan. On the other hand, utopianism is positively related to being flexitarian and lacto-ovo vegetarian. There are three other positive associations between the happiness constructs and the vegetarian identities: (a) virtue and pescatarians, (b) tranquility and fulfilment with flexitarians and pescatarians, and (c) satisfaction with flexitarians.

Another way of interpreting the results is looking at the rows in Table 4, that is, considering the heterogeneity of the relationships of each dietary identity with the different happiness constructs. Being an organic omnivore is not related to any happiness conceptualization, however the flexitarian identity is the one that is most significant in the eight models estimated. It is positively related to utopian, tranquility, fulfilment, and satisfaction, but negatively related to stoicism. Another identity showing heterogeneous relationships is lacto-ovo vegetarian, which is negatively related to stoicism and enjoyment, and positively related to utopian. Pescatarian has a positive relationship only with virtue, tranquility and fulfilment, while vegan is negatively linked only with utopian.

Concerning the control variables, age is positively related to some inner happiness constructs, stoicism and virtue, while it is negatively related to the utopian construct. As regards gender, females have a positive association with outer happiness constructs (satisfaction, carpe diem, and enjoyment), in addition to virtue. Income is positively related to stoicism, while being single is negatively related to this conceptualization. In addition, not having a partner negatively relates to carpe diem.

4.2 The Relationship Between Conceptualizations of Happiness and Vegetarian Scale

Table 5 shows the estimations with the variable for the self-identified dietary pattern—vegetarian scale—for people following a plant-based diet. According to the estimations, the higher the self-evaluation of a more vegetarian dietary pattern, the lower the agreement with stoicism, satisfaction and enjoyment happiness constructs, but the higher the agreement with tranquility. Control variables indicate a similar pattern to those in Table 3 for different dietary identities, but now age has a nonsignificant relationship with utopian and being a woman has a positive relationship with stoicism.

4.3 Discussion and Policy Implications

Considering the whole picture, we can analyze the findings from a more holistic perspective. If the policy goal is to increase engagement in vegetarian lifestyles, and the approach to achieve meat reduction is by paying attention to the philosophical ideas of being well, we can identify certain patterns. Figure 2 summarizes the different relationships obtained from the estimations.

We can draw several implications from the figure above:

-

(i)

There are conceptualizations of happiness that are not related to vegetarianism. Carpe diem is not related to any aspect of vegetarianism, or vegetarian identity or dietary pattern.

-

(ii)

There are happiness constructs that are clearly negatively related to vegetarianism. Stoicism is negatively related to lacto-ovo vegetarian and flexitarian identity, and to the vegetarian self-assessment scale, and enjoyment is negatively related to lacto-ovo vegetarian and to the vegetarian scale.

-

(iii)

There are conceptualizations that show a positive pattern in their relations with vegetarianism. Tranquility and fulfilment positively relate to flexitarian and pescatarian identities, while the rest of the relationships are nonsignificant. The virtue construct has a positive link with the pescatarian identity. There is also a positive association between tranquility and the vegetarian scale.

-

(iv)

There are conceptualizations that are heterogeneous in their relationships with vegetarianism. This heterogeneity may be due to the specification of the food identity variables, that are dummies, while the self-assessment scale ranges from 1 to 10. Also, this may be because people self-identify themselves as a particular food identity concerning meat consumption, while in the vegetarian scale they can rate differently. For instance, some flexitarian self-identified individuals may think they eat too much meat. In fact, satisfaction is positively associated with being flexitarian, but negatively with the vegetarian scale. This is also the case of utopian, which positively relates to flexitarian and lacto-ovo vegetarian identities, but negatively to identifying as a vegan.

-

(v)

Having explored the above linkages we suggest that if the goal of policy is to promote meat-reduced diets, then it may be worth taking into account the different ideas about leading a happy life that influence individual choices about following a vegetarian or non-vegetarian lifestyle. It seems that being in agreement with stoicism and enjoyment conceptualizations—that is, ‘‘happiness is accepting things as they are’’ and “happiness is to enjoy what one has attained in life”—could lead to lower levels of adoption of vegetarianism. Conversely, agreement with the tranquility, fulfilment, and virtue constructs—described respectively as “happiness is in living a tranquil life, not looking beyond what is attainable”, “happiness is in fully exercising our capabilities” and “happiness is a sense of acting properly in our relations with others and with ourselves”—is positively associated with vegetarianism. In line with the latter, there is evidence to suggest that a virtuous life may lead to the adoption of ethically-oriented veganism as an example of a good moral character, defined by Aristotle as “greatness of the soul”. Accordingly, the philosophical perspective of the ethics of virtue promotes respect for other beings, compassion, nonviolence, justice, and awareness of the environmental impact of food systems (Alvaro, 2017; Fox, 2013).

When looking at the identities in Fig. 2, two other policy implications emerge:

-

(f)

There is no relationship between being an organic omnivore and any of the happiness constructs, and

-

(g)

Being vegan, the most restrictive form of vegetarianism, has no positive relationship with any happiness construct. This means that there is no possibility of fostering those identities by focusing on a particular conceptualization of happiness. These results have also different interpretations in terms of morality since our findings indicate that identifying as a vegan is inversely related to the utopian construct (exhibiting the strongest relationship, b = 1.078, p < 0.01). Consequently, there is a relationship between vegans and disagreement with the statement “happiness is an unreachable ideal we can only try to approach”. Having explored the strong moral values among vegans and their firm commitment to animal and environmental welfare issues, our findings on philosophical constructs of vegans enrich the perspective on the idealistic vegan advocate (De Groeve & Rosenfeld, 2022). In contrast, flexitarians and lacto-ovo vegetarians who still consume some animal-based products and dairy and eggs, respectively, exhibit a positive link with agreement about happiness being an unreachable ideal, possibly due to their lower degree of commitment to avoiding animal products in comparison to vegans.

We have identified several inner- and outer-oriented happiness constructs that have different relationships with meat-reducer identities and self-reported vegetarian dietary patterns among overall higher-education students in Spain. Furthermore, exploring the correlations among our variables, we have found some links between motivations, CRT constructs, and vegetarianism. Accordingly, people driven to eschew meat for their health and other reasons positively relate to outer-oriented happiness constructs, fulfilment, satisfaction, and enjoyment. Conversely, the relationship with the ethical motivation for vegetarianism was statistically nonsignificant for the CRT constructs, but strongly related to the vegetarian scale. The latter aligns with prior evidence that the higher the motivation for vegetarianism, the greater the dietary restrictiveness related to meat consumption (Neale et al., 1993; Ruby, 2012). A possible explanation for the non-existent link between the ethical motivation for vegetarianism and the CRT constructs might reside in prior internalization of philosophical aspects of vegetarianism within the ethical framework of moral values for meat avoidance.

5 Limitations and Further Research

This research is not free of limitations. First, as we work with cross-sectional data, we cannot make causal interpretations. For instance, the positive association between utopian and flexitarians could mean that utopians tend to adopt this dietary identity, or that flexitarians tend to agree with the utopian vision of happiness. Second, the dataset used comes from a Spanish university, but ideally we would want to have a more representative and inclusive dataset. And third, we employed the self-reported dietary scale, which involves the participants making a subjective evaluation that may differ from their real dietary behavior. The ideal technique would be to use measures to monitor their food intake, providing more accurate information.

Concerning further research, it would be interesting to test these findings in different cultural backgrounds and age cohorts since personal views on life evolve over a person’s lifetime. In addition, motivations for adopting vegetarianism change over time, therefore, it would be valuable to explore how these changes can influence conceptualizations of happiness.

6 Conclusions

The purpose of the present research is to provide some evidence on the relationship between ideas of happiness concerning moral codes and vegetarianism. We use the Conceptual Referent Theory (CRT) to capture the different conceptualizations of happiness, along with the vegetarian identity and vegetarian self-assessment dietary scale to account for vegetarianism. Our findings suggest that there are some happiness constructs that are clearly positively related to both aspects of vegetarianism, psychological identity and dietary behavior, (particularly tranquility, virtue, and fulfilment) while others are clearly negatively related (stoicism and enjoyment). All happiness constructs are related to several vegetarian identities and the vegetarian scale, with the exception of carpe diem. In general, there is great heterogeneity in the relationships between the happiness constructs and the facets of vegetarianism. Some of them show heterogeneous relationships, such as satisfaction, which is positively related to being flexitarian but negatively to the vegetarian scale. Some constructs are related to inner or outer ideas of happiness, with the former type being more dependent on the self rather than what happens outside, and vice versa. Our results also suggest that people driven to eschew meat for their health and other reasons are associated with the outer-oriented happiness constructs, fulfilment, satisfaction, and enjoyment.

References

Agarwal, U., Mishra, S., Xu, J., Levin, S., Gonzales, J., & Barnard, N. D. (2015). A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a nutrition intervention program in a multiethnic adult population in the corporate setting reduces depression and anxiety and improves quality of life: The GEICO study. American Journal of Health Promotion, 29(4), 245–254.

Allen, M. W., Wilson, M., Ng, S. H., & Dunne, M. (2000). Values and beliefs of vegetarians and omnivores. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(4), 405–422.

Alvaro, C. (2017). Ethical veganism, virtue, and greatness of the soul. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 30(6), 765–781.

Aslanifar, E., Fakhri, M. K., Mirzaian, B., & Kafaki, H. B. (2014, September). The comparison of personality traits and happiness of vegetarians and non-vegetarians. In Proceedings of the SOCIOINT14-International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities, Istanbul, Turkey (pp. 8–10).

Beardsworth, A., & Keil, T. (1992). The vegetarian option: Varieties, conversions, motives and careers. The Sociological Review, 40(2), 253–293.

Beezhold, B. L., & Johnston, C. S. (2012). Restriction of meat, fish, and poultry in omnivores improves mood: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Nutrition Journal, 11(1), 9.

Bertella, G. (2020). The vegan food experience: Searching for happiness in the Norwegian foodscape. Societies, 10(4), 95.

Binder, M., Blankenberg, A. K., & Guardiola, J. (2020). Does it have to be a sacrifice? Different notions of the good life, pro-environmental behavior and their heterogeneous impact on well-being. Ecological Economics, 167, 106448.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2013). Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research, 114(3), 785–801.

Bouvard, V., Loomis, D., Guyton, K. Z., Grosse, Y., El Ghissassi, F., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., & Corpet, D. (2015). Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. The Lancet Oncology, 16(16), 1599–1600.

Campbell, T. M., II. (2004). The China study: the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted and the startling implications for diet, weight loss and long-term health. BenBella Books Inc.

Caviola, L., Everett, J. A., & Faber, N. S. (2019). The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(6), 1011.

Conner, T. S., Brookie, K. L., Carr, A. C., Mainvil, L. A., & Vissers, M. C. (2017). Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0171206.

De Backer, C. J., & Hudders, L. (2015). Meat morals: Relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behavior. Meat Science, 99, 68–74.

De Groeve, B., Hudders, L., & Bleys, B. (2021). Moral rebels and dietary deviants: How moral minority stereotypes predict the social attractiveness of veg*ns. Appetite, 164, 105284.

De Groeve, B., & Rosenfeld, D. L. (2022). Morally admirable or moralistically deplorable? A theoretical framework for understanding character judgments of vegan advocates. Appetite, 168, 105693.

Deckers, J. (2009). Vegetarianism, sentimental or ethical? Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 22(6), 573–597.

Devine, P. E. (1978). The moral basis of vegetarianism. Philosophy, 53(206), 481–505.

Dobersek, U., Wy, G., Adkins, J., Altmeyer, S., Krout, K., Lavie, C. J., & Archer, E. (2021). Meat and mental health: A systematic review of meat abstention and depression, anxiety, and related phenomena. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 61(4), 622–635.

Forestell, C. A., & Nezlek, J. B. (2018). Vegetarianism, depression, and the five factor model of personality. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 57(3), 246–259.

Fox, M. A. (2013). Vegetarianism and veganism. International encyclopedia of ethics (Vol. 9, pp. 5310–5316). Wiley-Blackwell.

Fox, N., & Ward, K. J. (2008). You are what you eat? Vegetarianism, health and identity. Social Science & Medicine, 66(12), 2585–2595.

Geerling, D. M., & Diener, E. (2018). Effect size strengths in subjective well-being research. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9670-8

Hamilton, M. (2006). Eating death: Vegetarians, meat and violence. Food, Culture & Society, 9(2), 155–177.

Hoffman, S. R., Stallings, S. F., Bessinger, R. C., & Brooks, G. T. (2013). Differences between health and ethical vegetarians. Strength of conviction, nutrition knowledge, dietary restriction, and duration of adherence. Appetite, 65, 139–144.

Iguacel, I., Huybrechts, I., Moreno, L. A., & Michels, N. (2020). Vegetarianism and veganism compared with mental health and cognitive outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews., 79, 361.

Jabs, J., Devine, C. M., & Sobal, J. (1998). Model of the process of adopting vegetarian diets: Health vegetarians and ethical vegetarians. Journal of Nutrition Education, 30(4), 196–202.

Jabs, J., Sobal, J., & Devine, C. M. (2000). Managing vegetarianism: Identities, norms and interactions. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 39(5), 375–394.

Jain, R., Degremont, A., Philippou, E., & Latunde-Dada, G. O. (2020). Association between vegetarian and vegan diets and depression: A systematic review. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665119001496

Janda, S., & Trocchia, P. J. (2001). Vegetarianism: Toward a greater understanding. Psychology & Marketing, 18(12), 1205–1240.

Krizanova, J., & Guardiola, J. (2020). Happy but vegetarian? Understanding the relationship of vegetarian subjective well-being from the nature-connectedness perspective of university students. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09872-9

Lea, E. J., Crawford, D., & Worsley, A. (2006). Consumers’ readiness to eat a plant-based diet. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 60(3), 342–351.

Leite, A. C., Dhont, K., & Hodson, G. (2019). Longitudinal effects of human supremacy beliefs and vegetarianism threat on moral exclusion (vs. inclusion) of animals. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(1), 179–189.

Lindeman, M. (2002). The state of mind of vegetarians: Psychological well-being or distress? Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 41(1), 75–86.

Lindeman, M., & Sirelius, M. (2001). Food choice ideologies: The modern manifestations of normative and humanist views of the world. Appetite, 37(3), 175–184.

Lindeman, M., & Stark, K. (1999). Pleasure, pursuit of health or negotiation of identity? Personality correlates of food choice motives among young and middle-aged women. Appetite, 33(1), 141–161.

Melina, V., Craig, W., & Levin, S. (2016). Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: vegetarian diets. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(12), 1970–1980.

Mujcic, R., & Oswald, J. A. (2016). Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1504–1510.

Neale, R. J., Tilston, C. H., Gregson, K., & Stagg, T. (1993). Women vegetarians: Lifestyle considerations and attitudes to vegetarianism. Nutrition & Food Science, 93(1), 24–27.

Ogden, J., Karim, L., Choudry, A., & Brown, K. (2007). Understanding successful behaviour change: The role of intentions, attitudes to the target and motivations and the example of diet. Health Education Research, 22(3), 397–405.

Pena-López, A., Rungo, P., & López-Bermúdez, B. (2021). The" efficiency" effect of conceptual referents on the generation of happiness: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(6), 2457–2483.

Radnitz, C., Beezhold, B., & DiMatteo, J. (2015). Investigation of lifestyle choices of individuals following a vegan diet for health and ethical reasons. Appetite, 90, 31–36.

Raphaely, T., & Marinova, D. (2014). Flexitarianism: A more moral dietary option. International Journal of Sustainable Society, 6(1–2), 189–211.

Remick, A. K., Pliner, P., & McLean, K. C. (2009). The relationship between restrained eating, pleasure associated with eating, and well-being re-visited. Eating Behaviors, 10(1), 42–44.

Rodríguez, L. (2001). Bienestar e ingreso: Un estudio sobre el concepto de felicidad (Puebla, Universidad de las Américas).

Rojas, M. (2005). A conceptual-referent theory of happiness: Heterogeneity and its consequences. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 261–294.

Rojas, M., & Vittersø, J. (2010). Conceptual referent for happiness: Cross-country comparisons. Journal of Social Research & Policy, 1(2), 103.

Romo, L. K., & Donovan-Kicken, E. (2012). “Actually, I don’t eat meat”: A multiple-goals perspective of communication about vegetarianism. Communication Studies, 63(4), 405–420.

Rosenfeld, D. L. (2018). The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite, 131, 125–138.

Rosenfeld, D. L. (2019). Ethical motivation and vegetarian dieting: The underlying role of anti-speciesist attitudes. Anthrozoös, 32(6), 785–796.

Rosenfeld, D. L., & Burrow, A. L. (2017). Vegetarian on purpose: Understanding the motivations of plant-based dieters. Appetite, 116, 456–463.

Rothgerber, H. (2017). Attitudes toward meat and plants in vegetarians. Vegetarian and plant-based diets in health and disease prevention (pp. 11–35). Academic Press.

Rozin, P., Markwith, M., & Stoess, C. (1997). Moralization and becoming a vegetarian: The transformation of preferences into values and the recruitment of disgust. Psychological Science, 8(2), 67–73.

Ruby, M. B. (2012). Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite, 58(1), 141–150.

Schenk, P., Rössel, J., & Scholz, M. (2018). Motivations and constraints of meat avoidance. Sustainability, 10(11), 3858.

Shapin, S. (2007). The history of vegetarianism. New Yorker.

Stoll-Kleemann, S., & Schmidt, U. J. (2017). Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Regional Environmental Change, 17(5), 1261–1277.

Twine, R. (2014). Vegan killjoys at the table—Contesting happiness and negotiating relationships with food practices. Societies, 4(4), 623–639.

Vice-Rectorate for Research and Knowledge Transfer. (2020). Code of Good Practice in Research. https://investigacion.ugr.es/sites/vic/investigacion/public/ficheros/extendidas/2020-02/Code%20of%20Good%20Practice%20in%20Research%20EN%20unido%202019.pdf. Last Accessed 26th February 2022.

Yokoyama, Y., Barnard, N. D., Levin, S. M., & Watanabe, M. (2014). Vegetarian diets and glycemic control in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, 4(5), 373. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2014.10.04

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Granada/CBUA. The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación and the European Regional Development Fund (project ECO2017–86822-R); the Regional. Government of Andalusia and the European Regional Development Fund (Projects P18-RT-576 and B-SEJ-018-UGR18) and the University of Granada (Plan Propio. Unidad Científica de Excelencia: Desigualdad, Derechos Humanos y Sostenibilidad -DEHUSO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JG. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JK and both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We would like to declare that we do not have any conflict of interest in reporting the results in this research. We have arrived to those by using statistical techniques and those are not politically oriented by any external organization.

Ethical Statement

The field work has been implemented under the ethical guidelines from University of Granada.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krizanova, J., Guardiola, J. Conceptualizations of Happiness and Vegetarianism: Empirical Evidence from University Students in Spain. J Happiness Stud 24, 1483–1503 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00650-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00650-6