Abstract

Emotions, like regret, have been heralded as instruments of self-regulation, by instigating reflection, learning and feedback for betterment and thus increasing well-being. Yet, this view neglects taking the frequency of regret into consideration. Frequently experiencing regret may instead be a sign of repeatedly failing to achieve betterment. Previous work has shown that people who experience regret often have lower life satisfaction. We suggest that, by itself, the reflective function of regret is not enough to lead to betterment. Rather, in addition to regret, self-regulatory abilities are needed. In the absence of these abilities, the reflective function of regret does not turn off but is likely to lead to frequent episodes of regret and turn into counter-productive rumination, reducing rather than increasing well-being. We tested these possibilities in two studies. In Study 1, reports were administered about regret frequency, self-regulatory abilities, and life satisfaction in 388 US adults (54.6% males; Mage = 35, SD = 10). In the preregistered Study 2, the same instruments were administered in a replication sample of 470 British adults (22.1% males; Mage = 36, SD = 12). In both studies, low self-regulatory abilities were associated with higher regret frequency, which in turn, was associated with poorer life satisfaction. Moreover, in both studies, the negative association between regret frequency and life satisfaction was explained by ruminative brooding styles. In sum, the positive reflective function of regret for well-being cannot stand alone, but needs self-regulatory abilities. Without these abilities, regret experience is frequent and its reflective function turns into brooding rumination that negatively affects well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

People sometimes make decisions that they later regret. Regret is an emotional experience that stems from the difference between the outcome of a chosen versus an unchosen option (e.g., Loomes & Sugden, 1982). Importantly, regret is seen as part of one’s self-regulatory abilities (Valshtein & Seta, 2019). In this view, feeling regret is an incentive to regulate future behavior (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). Baumeister et al. (2007) provide an explanation how this might work. Regret (and other negative emotions) shape behavior by way of cognition or affect (Buchanan et al., 2016). Regret may yield divergent outcomes produced by these different components of regret. Whereas the affective experience produced by the negative event yields negative outcomes, the cognitive understanding of the poor decision would lead to learning and betterment (Buchanan et al., 2016; Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). Thus, in addition to the fact that self-regulatory abilities directly affect well-being (Elliot et al., 2011; Robinson, 2007), the cognitive component of regret may be a self-regulatory device affecting well-being all by itself. It is taken to stimulate reflection and retrospective appraisal of actions, thereby providing guidelines for future behavior. Learning from one’s mistakes involves the use of anticipated regret (Zeelenberg, 1999).

This positive function of regret has been described in similar ways in the literature (Roese, 2005). Regret indicates incongruence between behavior and one’s goals (Valshtein & Seta, 2019) and involves counterfactual thinking (for example, ‘what would have happened if I had done otherwise?’) coupled with possible repair (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). Regret may actually function as an error signal in the brain that provokes learning (Bourgeois-Gironde, 2010). Regret may thereby contribute to promoting well-being and positive development (King & Hicks, 2007). A thought experiment along these lines would suggest that people experiencing frequent regret would therefore frequently reflect through retrospective appraisal, learn from this, apply their insights to future behavior, and hence improve their well-being. Yet, something does not seem right. Previous work found that people who experience regret often have lower life satisfaction (e.g., Newall et al., 2009). Bourgeois-Gironde (2010) also showed that even though regret generates error signals in the brain, for people who are addicted (and thus lack self-control), these signals can be dissociated from behavior. Somebody who experiences frequent regret is likely somebody who fails to learn the lessons from past behavior, rather than somebody who draws many lessons from it.

Contrary to the conjecture by Baumeister et al. (2007), the cognitive component of the emotion of regret may not be self-regulatory all by itself. Instead, self-regulatory abilities may be needed in addition to the cognitive side of the emotion. This leads us to the conjecture that with low self-regulatory abilities, the emotion of regret will not increase well-being via reflection on past behavior and drawing guidelines for the betterment of one’s future behavior. It is known that people vary in the degree to which they have the ability to avoid decisions they regret (e.g., Lindenberg, 2013). Low self-regulatory abilities are likely to lead to frequent experiences of having done something one regrets, especially in recurring daily activities.

The mechanism may be as follows. Low self-regulatory abilities may lower the reflective function of regret, thereby leading to more episodes of regret, which turns the reflective function into dysfunctional rumination, with negative effects on well-being (Rude et al., 2007). In other words, with low self-regulatory abilities and high regret frequency, the cognitive side of regret still registers that a different choice could have led to a better outcome, but in each regret episode the reflection is likely to be sidetracked, away from retrospective appraisal of actions and learning towards brooding rumination with self-critical anxious pondering about what happened and keeps happening, adding a stronger emphasis on the affective side of regret.

There are some indications in the literature for this mechanism. For example, Thomsen et al. (2011) found that less internalized self-regulation was related to more rumination. Moreover, Baskin-Sommers et al. (2016) found that for individuals scoring high on psychopathic traits –implying poor impulse control – the experience of regret did not alter their behavior in decision-making tasks. This view implies that being much preoccupied with having behaved in a regrettable way and with thinking about it, is more a sign of frequent experience of having behaved in a regrettable way than of problem solving reflections.

Epstude and Roese (2008) already pointed to the possibility that regret is a double-edged sword, and Inman (2007, pp. 20–21) proposed research in this direction: “I advocate research that seeks to separate the beneficial aspects of regret from the more deleterious aspects. To the extent that it makes us a better decision maker or helps us learn, then regret can be beneficial. To the extent that it leads to self-reproach and its ugly stepchildren, self-doubt and self-loathing, regret is something to be avoided.” Yet, regret may not be easy to avoid, if one’s self-regulatory abilities are low. To the best of our knowledge, the role of low self-regulatory abilities with regard to the reflective function of regret and well-being, has not been investigated. Our predictions are depicted in Fig. 1. To summarize, we hypothesize a positive association between poor self-regulatory abilities and regret frequency (arrow 1) and a direct negative association between poor self-regulatory abilities and life-satisfaction (arrow 2). Moreover, we hypothesize that regret frequency is negatively associated with life satisfaction because of more brooding rumination (mediation; arrows 3).

Model of the predicted role of poor self-regulatory abilities and rumination for the function of regret experience for well-being. Line 2a is not part of our theory and represents our test of a possible moderating influence of poor self-regulatory ability on the link between frequency of regret experience and well-being

If our conjectures turn out to be right, it would entail an important lesson on the workings of emotions with regard to self-regulation: emotions like regret must be linked to self-regulatory abilities to perform their positive function; if they are not linked this way, they may actually lower well-being. Conversely, this would also entail an important message about self-regulatory abilities. They are not just “the [in]ability to override or change one’s inner responses, as well as to interrupt undesired behavioral tendencies (such as impulses) and refrain from acting on them” (Tangney et al., 2004, p. 274), but also abilities to make us reflect and learn with the aid of emotions. In two studies, we aim to test these intricate relationships between self-regulatory abilities, regret frequencies, reflection/rumination and well-being. In the first study, we used regret with regard to things one has done (commission) and focused on regret frequency, well-being, poor self-regulatory abilities, and reflection/rumination. In the second study, we sought to replicate results from the first study and to find out whether these results also hold for regret about what one failed to do (omission).

1.1 Study 1

In Study 1, we investigated well-being (operationalized as life satisfaction) as being negatively related to poor self-regulatory abilities, and negatively related to regret frequency and reflection/rumination. Even though the model depicted in Fig. 1 is causal and our research is only cross-sectional, we can derive predicted associations from it and attempt to answer the following questions: First, are low self-regulatory abilities positively associated with experienced regret frequency? Second, is regret frequency indeed inversely related to life satisfaction? Third, is (a) regret frequency positively associated with reflection/rumination, and (b) to what extent do reflection and rumination explain the association between regret frequency and life satisfaction? In all analyses, we controlled for sex, age, and educational level, as previous work remains inconclusive about the role of these demographic factors in explaining regret (Newall et al., 2009; Roese et al., 2009).

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Data were collected via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and comprise a sample of 388 adults from the general population in the US (54.6% males; Mage = 35.02, SD = 9.81, age range 18 to 70). One participant did not fill out his age. Participants were collected via ads on Mechanical Turk in spring 2017 and filled out the questionnaire online. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the authors’ institution and adheres to ethical principles of the APA. The current sample size was sufficient (i.e., statistical power 80%) to discern small to moderate effects in multiple linear regression models with 5 to 12 independent variables (Faul et al., 2009).

The majority of the participants were White (73.2%) and a minority was Black or African American (11.1%), Asian/ Pacific Islander (7.0%), Hispanic or Latino (6.2%), or another ethnicity (2.6%). More than one-third (36.8%) were married or in a romantic relationship, whereas the other participants were single (56.2%), divorced (6.2%), or other (1.3%). Participants’ educational level varied from no education (0.5%), high school education (14.2%), vocational training (2.8%), some college education (25.5%), Associate degree (12.1%), Bachelor’s degree (37.6%), and a Master’s degree or higher (7.2%). Most participants had a paid job (i.e., employed for wages or self-employed) (83.0%) and a minority was out of work (7.4%), a homemaker (4.9%), student (2.3%), or other (2.3%).

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Regret Frequency

How should regret frequency be measured? Previous studies largely dealt with regret as related to a specific regretful event (e.g., ‘what is your biggest regret?’), assessed regret using vignettes, relied on autobiographical recall of specific regrets, or focused on regret proneness (e.g., Breugelmans et al., 2014; Komiya et al., 2016; Schwartz et al., 2002). Moreover, that work largely focused on the functionality of regret, for example for correcting one’s behavior (e.g., Bjälkebring et al., 2016). Although there is some work that examines the frequency of regret, it is always related to either one regretful activity (e.g., Moore & McElroy, 2012), regret in general (e.g., Newall et al., 2009), or intense life regrets (e.g., Lecci et al., 1994; Roese & Summerville, 2005). Interestingly, Saffrey et al. (2008) studied both the intensity and frequency of anger, anxiety, boredom, disappointment, fear, guilt, jealousy, sadness, and regret. Participants rated regret as being the most intense of these negative emotions and second most frequent (anxiety was rated as the most frequent negative emotion). This research informs us about the relative frequency of these emotions, but not about individual differences in the frequency with which people feel regret. Others have also suggested that people experience regret over decisions on a daily basis (e.g., Bjälkebring et al., 2016) and that these may differ from life regrets in that the former may be more readily repaired (Summerville, 2011; Västfjäll et al., 2011). We argue that if we want to examine failure of the correcting function of regret, it is important to focus on decisions in everyday activities and situations, and on the frequency with which one experiences regret about these decisions. These kinds of decisions occur over and over again and therefore are particularly useful for tracing the correcting function of regret. In contrast to life regrets, which are singular and often difficult to repair, we tap into regret over common daily activities, which can meaningfully vary in frequency and be repaired by behavioral change. A high frequency of regret for such activities would indicate that time and again, the experience of regret did not lead to correction of one’s behavior regarding the next time, negatively affecting well-being.

The frequency of regret experiences was thus assessed via the Regret Frequency Inventory (RFI) that specifically targets everyday situations, which was developed by the third author. Participants indicated how often they experience regret over nine activities of daily living (e.g., ‘staying in bed for too long’ and ‘being too unfriendly’; see Appendix), on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (every day). The original 10-item version of the RFI was developed for and tested in a community sample (N = 455; age 18 – 94; α = 0.71) by the third author, as an add-on to a study on well-being (see Steverink et al., 2020). Construct validity was shown by sizable negative correlations of RFI scores with life-satisfaction and self-rated life achievement compared to others, and sizable positive correlations with feeling constantly under strain, not being able to overcome difficulties, losing confidence in oneself, and thinking of oneself as worthless. In the current study, we omitted one item due to being formulated as regret over things one did not do (i.e., omission). The current instrument thus included nine items, which were averaged to represent a general score of regret frequency (α = 0.83).

2.2.2 Poor Self-regulatory Abilities

Self-regulation prominently includes the ability to consider the consequences of one’s decisions and act accordingly. Low self-regulatory ability can be based on one’s anxiety to act because one (often falsely) anticipates failure (sensitivity to punishment); it may be based on being too much focused on getting a reward, often disregarding possible failure (sensitivity to reward); and it may be based on impulsivity (acting without much deliberation) and impulsive antisociality (a tendency to fail at inhibiting antisocial impulses). We consider all four forms of low self-regulatory ability.

2.2.2.1 Sensitivity to Reward and Sensitivity to Punishment

The short version of the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (Cooper & Gomez, 2008) was administered. The instrument contains 24 items, all rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). One subscale related to sensitivity to punishment (14 items, α = 0.94) and one to sensitivity to reward (10 items, α = 0.80). Sensitivity to punishment refers to passive avoidance of situations that potentially involve aversive consequences and concern for punishment or failure. Example items are: ‘Are you often afraid of new or unexpected situations?’, “Are you easily discouraged in difficult situations?’ Sensitivity to reward refers to situations that involve potential social or monetary rewards. An example item of the sensitivity to reward scale is: ‘Do you like displaying your physical abilities even though this may involve danger?’, “Do you generally give preference to those activities that imply an immediate gain?” Higher scores on the subscales indicate more sensitivity to punishment and reward respectively.

2.2.2.2 Impulsivity and Impulsive Antisociality

We included the Impulsive Antisociality (IA) scale from the International Personality Item Pool – Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness inventory (Wit et al., 2009). Participants rated whether 20 statements applied to them on 4-point Likert scales ranging from 0 (completely disagree) to 3 (completely agree). Four items comprised the subscale impulsivity (α = 0.88), including items such as ‘I make rash decisions’ and ‘I rush into things.’ The other 16 items comprised the impulsive antisociality subscale (α = 0.94), that measures a tendency to fail at inhibiting antisocial impulses. It included items such as ‘I take no time for others’ and ‘I get back at others.’ Items were averaged for each subscale. Notice that even though these two scale measures what may be seen as inappropriate behavior, they do not in any way imply that people feel regret behaving or having behaved this way.

2.2.3 Rumination/Reflection

The Response Style Questionnaire (Treynor et al., 2003) contains two subscales to measure potentially dysfunctional critical self-focused attention. The items of both subscales tap into the frequency with which one does something when one feels bad. One subscale is called “reflection” (three items,Footnote 1 averaged for subscale, α = 0.76) and deals with attempts to overcome feeling bad, as would be the case after feeling regret about having done something or failed to have done something. The other subscale is called “brooding” (five items, averaged for subscale, α = 0.88) and deals with a moody kind of pondering about feeling bad. The items of both subscales tap into the frequency with which one does something when one feels bad rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Example items for reflection are ‘write down what you are thinking and analyze it’ and for brooding ‘Think “why can’t I handle things better?”’.

2.2.4 Life Satisfaction

The 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (α = 0.94) was used (Diener et al., 1985) (e.g., ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’). Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and averaged to represent a general score.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means, standard deviations, and ranges of all observed study variables are presented in Table 1. To test for mean differences between males and females we used independent samples t-tests. Males and females did not differ in their regret frequency, t(386) = 0.49, p = 0.63. Males reported significantly more impulsive antisociality and sensitivity to reward compared to females (ts(386) > 3.39, ps < 0.01). Pearson correlations between poor self-regulatory abilities and regret frequency were all significant, positive, and moderate to large in size (ranging from 0.43 to 0.54). Life satisfaction was negatively associated with various indicators of self-regulatory abilities as well as regret frequency, suggesting that individuals who report lower self-regulatory abilities and lower regret frequencies report more life satisfaction. Finally, younger individuals were likely to report higher regret frequencies.

3.2 Self-Regulatory Abilities, Regret Frequency, and Life-Satisfaction

We assumed that poor self-regulatory ability would lower the reflective function of regret, thereby leading to higher regret frequency and brooding, with negative consequences for life satisfaction. We thus tested first whether self-regulatory abilities were associated with regret frequency. To this end, we ran a multiple regression, while accounting for age, sex, educational level, and all other self-regulatory abilities. Impulsivity and impulsive antisociality traits were associated with higher frequency of regret, b = 0.15, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.25, and b = −0.28, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.16, 0.40, respectively (arrow 1 in Fig. 1). Similar associations were found for sensitivity to reward, b = 0.28, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.17, 0.39, and sensitivity to punishment, b = 0.21, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.14, 0.28. This supports our hypothesis that problematic self-regulation traits are associated with higher regret frequency, jointly explaining almost 40% of the variance in regret frequency.

To test whether regret frequency was indeed inversely related to life satisfaction (arrow 3a in Fig. 1), we also conducted a linear regression analysis, while accounting for age, sex, and educational level (see Table 2). Analyses indicated that regret frequency was negatively associated with life satisfaction, suggesting that those with higher regret frequency reported lower life satisfaction. Partial squared correlations indicated a small to medium effect size.

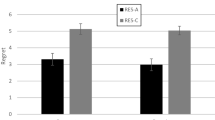

Next, we examined the possibility that, in addition to what we had hypothesized, poor self-regulatory abilities would modify the association between regret frequency and life satisfaction (arrow 2a in Fig. 1; Table 2). It could be that poor self-regulatory abilities exacerbate the negative influence of regret frequency on well-being, and this possibility seemed worth testing. Interactions were tested for impulsivity and sensitivity to reward and punishment separately. In all models, we again accounted for differences in sex, age, and educational level. For sensitivity to reward and punishment, we found no moderation of the association between regret frequency and life satisfaction. Rather, model 2 in Table 2 shows that higher levels of sensitivity to punishment were associated with lower life satisfaction, while the effect of regret frequency became insignificant. By contrast, we found a significant positive interaction between regret frequency and impulsive antisociality (b = 0.22, SE = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.44) with regard to life satisfaction (see Fig. 2A). What does this mean? For respondents with average (b = −0.48, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = −0.68, −0.28) or low (b = −0.70, SE = 0.16, 95% CI = −1.01, −0.38) levels of impulsive antisociality, there was a stronger negative association between regret frequency and life satisfaction. The Johnson-Neyman significance region became significant at impulsive antisociality mean-centered values of 0.90 or lower, which comprised 81.1% of the sample. Because this interaction was not expected, we took a closer look at the diagonal extremes (see Table 3), which reveals that only a small number (6.8%) of those who had low impulsive antisociality also reported high regret frequency. Conversely, only a small number (1.6%) of those who had high impulsive antisociality also reported low regret frequency. The interaction thus seems to be driven by these few extreme cases and does not add much to the mechanism already described in Fig. 1. What it shows is that high impulsive antisociality lowered life satisfaction all by itself (arrow 2 in Fig. 1), even for those few who had low regret frequency, and high regret frequency lowered life satisfaction even for those few who had low impulsive antisociality as well as high regret frequency. The latter effect was not predicted by us.

3.3 Mediation by Ruminative Styles

Finally, we tested our hypothesis concerning the role of brooding mediating the relationship between regret frequency, and life satisfaction (arrows 3 in Fig. 1). We tested this in two steps. First, we argued that for people with poorer self-regulatory abilities, reflection would be lowered and, with frequent regret episodes, would actually turn into brooding rumination rather than problem analysis and learning. To test this, we calculated correlations between self-regulatory abilities and ruminative styles. Table 1 shows that poorer self-regulatory abilities are related to more reflection (rs > 0.14), but that this reflection is not related to problem solving but to rumination can be gleaned from the fact that self-regulatory abilities are also (and even more strongly) related to brooding (rs > 0.20). Brooding seems to be the dominant kind of self-reflection in this context. Fisher’s r-to-z tests showed that sensitivity to punishment, impulsivity, impulsive antisociality were all more strongly related to brooding than to reflection (zs > 1.98, ps < 0.05). Moreover, compared to reflection, brooding was more strongly associated with regret frequency and life satisfaction (zs > 2.64, ps < 0.01).

Second, the dominance of self-reflection as brooding (when one experiences frequent regret) also shows up by the fact that brooding, but not reflection, explains the association between regret frequency and life satisfaction. We conducted a mediation analysis using bootstrapping via the PROCESS module in SPSS (Hayes, 2018), while controlling for sex, age, and educational level. Regret frequency was negatively associated with life satisfaction (b = −0.072, SE = 0.14, 95% CI = −1.00 to −0.45). When including brooding and reflection to the model, this association was fully explained by brooding (b = −0.58, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = −0.075 to −0.42), rendering the direct association between regret frequency and life satisfaction non-significant. Brooding was thus found to be harmful to life satisfaction whereas reflection was simply ineffectual, which can be gleaned from the fact that it failed to have a significant association (and no negative association) with life-satisfaction (b = 0.08, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = −0.00 to 0.18).

4 Discussion

Study 1 tested our prediction (depicted in Fig. 1) that in the absence of self-regulatory abilities, regret will be frequent and its reflective function will turn into brooding rather than learning, which, in turn negatively affects life satisfaction. The model itself is causal, but our test only allows for associations. Still, our results support the associations derived from the model for impulsive antisociality as a form of low self-regulatory ability. Impulsive antisociality was negatively related to life satisfaction and positively related to regret frequency, which, in turn, was negatively associated with life satisfaction. Brooding fully explained the link between regret frequency and life satisfaction. This thus indicates that when regret is experienced frequently (as would be the case with low self-regulatory abilities), the correcting function of reflection following regret that has been heralded in the literature (Baumeister et al., 2007) does not materialize. To the contrary, the reflective function turns into harmful brooding that is negatively associated with life satisfaction. Reflection as measured here, e.g., with items such as “analyze recent events and try to understand why you are depressed”, also increased with regret frequency. It is thus likely that people, who do not experience regret frequently, may also not reflect on feeling bad as much and what to do about it when they experience regret. Rather, the negative emotion may motivate reflecting on ways to do things better. If true, this would mean that the way in which frequent experience of regret deflects the reflective function, is by focusing on feeling bad, rather than on what to do better next time. This represents a shift of the cognitive component of regret in the affective direction.

Our results also show that not all poor self-regulatory abilities negatively affected life satisfaction via regret frequency. We saw that sensitivity to punishment is negatively associated with life satisfaction, without any role for regret frequency. In addition, despite substantial overlap between impulsivity and impulsive antisociality, the current findings showed that the relevant problematic self-regulatory ability is the inability to inhibit antisocial impulses rather than general behavioral impulses. This suggests that, while the relationship between impulsive antisociality and life satisfaction can be partially explained by regret frequency, this is not the case for the relationship between sensitivity to punishment and life satisfaction. Seemingly, not all kinds of indicators for low self-regulatory abilities are linked to life satisfaction via regret frequency, which modifies our model (Fig. 1) to apply only to impulsive antisociality.

These findings highlight important links between regret frequency, self-regulatory abilities, brooding, and life satisfaction, and replication of these associations is needed. Moreover, it is important to capture the breath of regret frequency: are the results different for regret about what one has failed to do, rather than what one did? In Study 1, we only assessed regrets of commission items and not of omission. Would other kinds of self-regulatory abilities come into play when regret is about omission rather than commission? Because we are dealing with regrets about daily activities (“I should not have drunk so much”) rather than life regrets (“I shouldn’t have married so early”), we do not expect to find different results for omission compared to commission. After all, the focus is not so much on what might have been but on the fact that one did it (or failed to do it) again.

To find out whether our results from Study 1 replicate and whether the results for omission regret frequency are indeed similar to those of commission regret frequency, we conducted another study. Our general prediction for Study 2 was that we would find similar results for both regret over omission and commission and we preregistered this study via AsPredicted #10,167 (http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=xs6n9b, April 2018).

5 Study 2

In Study 2, we replicated the analyses from Study 1 to test the associations between regret frequency, poor self-regulatory abilities, and life satisfaction, while controlling for sex, age, and educational level in a sample from a different country (the United Kingdom rather than the United States). Moreover, we included not just commission regret but also omission regret frequency.

5.1 Participants and Procedure

To replicate the findings with enough statistical power (80%) to discern small effects, the required sample size is 395 for a multiple linear regression model with 5 to 12 independent variables (Faul et al., 2009). We decided to oversample to account for missing data and other unforeseen circumstances. Data for Study 2 were collected via ads on Prolific Academic in spring 2018 and comprised a sample of 470 adults from the general population in the United Kingdom (22.1% males; Mage = 36.38, SD = 12.01, age range 18 to 75). Two participants did not fill out their sex and age. In addition, 10 participants had missing information on one or more of the measures of interest, resulting in a sample of 458 participants. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the authors’ institution and adheres to ethical principles of the APA.

The majority of the participants were White (88.9%) and a minority was Asian (4.5%), mixed or multiple ethnic groups (3.4%), Black, African, Caribbean (1.5%), or another ethnicity (1.7%). More than half of the sample (59.1%) were married or in a romantic relationship, whereas the other participants were single (34.7%), divorced/separated (4.5%), or other (1.7%). Participants’ educational level varied from no high school diploma (4.9%), high school education (17.9%), vocational training (11.3%), some college education (16.6%), Associate degree (2.3%), Bachelor’s degree (33.2%), and Master’s degree or higher (13.3%). Most participants had a paid job (i.e., employed for wages or self-employed) (65.5%) and a minority was out of work (3.8%), a homemaker (12.3%), student (7.2%), or other (11.2%).

5.2 Instruments

To replicate the findings from Study 1 we included the same instruments to assess poor self-regulatory abilities and life satisfaction. To assess regret frequency, we included the same items for assessing regret from commission, but also included nine omission items. These items assessed regret over not having done something. Participants indicated how often they experience regret over certain activities of daily living that they did not do (e.g., ‘did not exercise enough’ and ‘did not listen enough to what other people say”; see Appendix), on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (every day). The nine items (α = 0.84) were averaged to represent a general score of regret omission frequency.

6 Results

6.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations for commission regret frequency

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all observed study variables are presented in Table 1. As in Study 1, males and females did not differ in their total regret frequency, t(460) = 0.24, p = 0.81. Males reported significantly more impulsivity, impulsive antisociality, and sensitivity to reward compared to females, ts(457–460) > 2.05, ps < 0.05. Similar to Study 1, correlations between poor self-regulatory abilities and regret frequency were all significant, positive, and modest to large in size with correlations ranging from 0.29 to 0.49. Life satisfaction was negatively associated with regret frequency. Finally, younger individuals reported higher regret frequencies.

6.2 Self-Regulatory Abilities, Regret Frequency, and Life-Satisfaction

First, we replicated the analyses from Study 1 by assessing the association between self-regulatory abilities and commission regret frequency. To this end, we again ran a multiple regression, while accounting for age, sex, and educational level. All traits were associated with higher frequency of regret (arrow 2 in Fig. 1), jointly explaining almost 30% of the variance in commission regret frequency.

Next, we analyzed the association between commission regret frequency and life satisfaction (see Table 4). In line with Study 1, regret frequency was again negatively associated with life satisfaction, suggesting that those with higher regret frequency reported lower life satisfaction. Partial squared correlations indicated a small to medium effect size.

We also replicated the test of the interaction between regret frequency and poor self-regulatory abilities in the explanation of life satisfaction (see Table 4; Fig. 2B). Similar to Study 1, there was a significant positive interaction between impulsive antisociality and regret frequency (b = 0.18, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.03, 0.32). The interpretation of this interaction is the same as for Study 1. For respondents with average (b = −0.34, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = −0.50, −0.18) or low (b = −0.52, SE = 0.12, 95% CI = −0.76, −0.28) levels of impulsive antisociality, there was stronger a negative association between regret frequency and life satisfaction. This applied to the majority of the participants, as the Johnson-Neyman significance region for this association became significant at impulsive antisociality mean-centered values of 0.89 or lower, which comprised 84.7% of the sample. Looking at the diagonal extremes (see Table 3), we see a replication of the results for Study 1: only a small number (4.9%) of those who had low impulsive antisociality also reported high regret frequency. Conversely, only a small number (5.7%) of those who had high impulsive antisociality also reported low regret frequency. Thus, also in Study 2, the interaction is driven by these few extreme cases. In short, we again found that high impulsive antisociality lowered life satisfaction all by itself, even for those few who had low regret frequency (arrow 2 in Fig. 1), and that high regret frequency lowered life satisfaction even for those few who had low impulsive antisociality as well as high regret frequency.

Moreover, also with regard to sensitivity to reward and punishment, we find results that are virtually identical to those of Study 1 (see Table 4). Higher levels of sensitivity to punishment are associated with lower life satisfaction, while the effect of regret frequency became insignificant. This suggests again that only impulsive antisociality, and not the other kinds of low self-regulatory ability, is linked to life satisfaction via regret frequency (a modification of our original prediction).

6.3 Ruminative Styles

Next, we replicated the test that people with lower self-regulatory abilities would engage more in ruminative styles related to brooding and ineffectual reflection. To test this, we calculated correlations between self-regulatory abilities and ruminative styles. Both reflection and brooding were again positively related to poor self-regulatory abilities, but this time, reflection was related a bit more strongly to poor self-regulatory abilities than brooding (rs > 0.18 versus rs > 0.14, respectively; see Table 1). Fisher’s r-to-z tests showed that only sensitivity to punishment was more strongly related to brooding than to reflection (z = 4.93, p < 0.001), whereas all other correlations did not differ significantly between these ruminative styles.

The dominance of brooding as a form of self-reflection (for subjects with high frequency regret and poorer self-regulatory abilities), was also found in Study 2. A summary of this analysis is presented in Fig. 3B. Regret frequency was negatively associated with life satisfaction (b = −0.63, SE = 0.13, 95% CI = −0.88 to −0.38). When including brooding and reflection to the model, this association was fully explained by brooding (b = −0.58, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = −0.76 to −0.41), rendering the direct association between regret frequency and life satisfaction insignificant. Reflection again proved to be ineffectual, showing neither negative nor positive relations to life satisfaction (b = 0.00, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = −0.12 to 0.12).

Bootstrapped analyses of the association between regret frequency and life satisfaction mediated by brooding and reflection in study 1 (Fig. 3a) and 2 (Fig. 3b). Dashed lines indicate non-significant associations, whereas solid lines indicate significant associations. These models were estimated while controlling for sex, age, and educational level

6.4 Omission Regret Frequency

Finally, all analyses in Study 2 were also repeated for regret frequency with regard to omission (i.e., regret over something that one did not do) These analyses yielded findings that were similar to the results of commission regret frequency in terms of direction of associations, effect sizes, and significance, and hence we report them here only briefly.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for omission regret frequency are reported in Table 1. Assessing the association between self-regulatory abilities and commission regret frequency, showed that all self-regulatory abilities were associated with higher frequency of regret, while accounting for age, sex, and educational level. Analyses related to test the interactions with poor self-regulatory abilities are reported in the online supplement, in Table S1. Findings were similar to those from the analyses on commission regret frequency and life satisfaction. That is, omission regret frequency was negatively associated with life satisfaction, suggesting that those with higher regret frequency reported lower life satisfaction. Partial squared correlations indicated a small to medium effect size. In contrast to commission, there was no significant interaction between impulsive antisociality and regret frequency (b = 0.15, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = −0.01, 0.31), the effect and confidence intervals were largely similar to those for commission regret frequency. Moreover, with regard to sensitivity to reward and punishment, results were similar to those of commission regret frequency (see Table 4). Higher levels of sensitivity to punishment were associated with lower life satisfaction, but the effect of regret frequency became weaker.

The role of reflection and brooding in the association between regret frequency omission and life satisfaction was also tested (see online supplement, Figure S1). Regret frequency omission was negatively associated with life satisfaction (b = −0.51, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = −0.69 to −0.34). Similar to the analyses for regret frequency commission, this association was largely explained by brooding (b = −0.39, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = −0.52 to −0.27), whereas reflection was not significantly related to life satisfaction (b = 0.01, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = −0.19 to 0.22).

7 Discussion

First and foremost, Study 2 largely replicated the findings from Study 1. Associations derived from the model (Fig. 1) were again supported for impulsive antisociality. Our expectation that the effects for regret about omission would not differ from those of regret commission was also supported. This means that regret over omission did not relate to problematic self-regulatory abilities in a way that is different from regret over commission.

8 General Discussion

In two studies, we examined the link between the prevalence of regret over daily activities with life satisfaction. We particularly focused on the possibility that regret is not always an emotion that contributes positively to life satisfaction through its reflective function. We are certainly not the first to consider this possibility (see Inman, 2007; Epstude & Roese, 2008; Broomhall et al., 2017). However, what is new in our research is the focus on the role of self-regulatory abilities. We argued that for the positive reflective function of regret to materialize, people need self-regulatory abilities. Lacking these abilities will result in the frequent experience of regret over daily activities, which, in turn, will focus the reflective function of regret on repetitive self-focused attention to feeling bad (thereby lowering well-being).

The results from both studies support this prediction for particularly one kind of low self-regulatory ability: impulsive antisociality. Other kinds, such as sensitivity to reward and sensitivity to punishment, and general impulsiveness, did not affect well-being via regret frequency and brooding, even though they all had a positive association with regret frequency. We can only speculate why this is so. Interestingly, there seems to be a specific social component involved: general impulsivity, as one kind of low self-regulatory ability, did not affect well-being via regret frequency, only the inability to inhibit antisocial impulses (impulsive antisociality) did so. Moreover, many of the items included in the Regret Frequency Inventory are also social by nature (e.g., being unfriendly, hanging with the wrong crowd, showing too little empathy). This is not surprising as many of our daily activities we might regret (such as “drank too much alcohol” or “have been too unfriendly”) relate to consequences for others, whose reaction is important to us. Being able to inhibit the impulse not to think of others, may thus be especially important for avoiding those behaviors that trigger negative reactions from others that make us not only feel bad about what we have done, but also repetitively make us feel bad about ourselves (“why do I have problems other people don’t have?”; “why can’t I handle things better?”), which is apt to lower life satisfaction. In short, for the link between regret frequency and well-being, the social component of self-regulation proves to be particularly important (Lindenberg, 2015).

Study 2 also showed that the proposed model holds for both commission regret frequency and for omission regret frequency. This is interesting in light of research that shows that (in the short run) people experience stronger regret about things one has done than about things that one has failed to do (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). As related above, the reason we did not expect a difference in our studies between these two kinds of regret, is that when it comes to the link between low self-regulatory ability and regret frequency in activities of daily life (such as “having been too unfriendly”), the focus for both commission and omission is the same: the fact that one again did (or failed to do) something one has regretted before.

These results tell us something important about the role of emotions that have a self-regulatory function. Baumeister et al. (2007) elaborated this self-regulatory function by suggesting that these kinds of emotions make people reflect and therefore learn. They state: “The more intense the emotional state, the more cognitive reflection is likely to occur (cf. Roese, 1997). Bad emotions may do this more powerfully and effectively than good ones (Baumeister et al., 2001).” They explicitly mention regret as an example of such a strong “bad” emotion (i.e., bad feeling). Our studies conditionalize this insight. They show that the reflective function of negative emotions is likely to turn into dysfunctional rumination if the person does not have the self-regulatory ability to trigger this function. In fact, the inability to inhibit antisocial impulses may also lead to inhibiting a focus on reflection and learning how to avoid actions that negatively affect others. Not learning from one’s regretted actions means repetitive experience of regret, leading to self-doubt and lower well-being (Rude et al., 2007).

By the same token, our studies also teach us a lesson about self-regulation. Self-regulatory abilities are strengthened by negative emotions to make one adapt one’s behavior so that it will increase rather than decrease well-being. Thus, the toolkit of self-regulation may prominently contain emotions that are yoked to certain self-regulatory abilities and work in tandem with these abilities. In the case of regret over daily activities and self-regulation, the yoked self-regulatory ability seems to be the ability to inhibit antisocial impulses. Other self-regulatory abilities are likely yoked to other emotions than regret, which would be an interesting topic for future research.

The findings of the current studies should be interpreted in light of some limitations. For one, given the cross-sectional design, we were not able to examine causal mechanisms or longitudinal associations between regret frequency, rumination, and life satisfaction. In that sense, it could be that individuals who report lower life satisfaction are more likely to brood and as a result rehash regret experiences or are more likely to see the regrettable side of their decisions, thus suggesting bi-directional relationships between regret frequency and life satisfaction. Despite this limitation, the data clearly supported the various associations that could be derived from the causal mode. This provides an overview of the correlates of self-regulatory abilities and regret frequency, and of the potential mechanisms of the link between regret frequency and life satisfaction, all of which may inform future longitudinal research.

Another limitation is that we did not explicitly include testing a possible reduction of cognitive reflection as an inverse function of self-regulatory abilities. Instead, we focused exclusively on testing the increase in brooding and dysfunctional reflection as a function of low self-regulatory abilities. In future research about the reflective function of regret, it would be wise to consider the possibility, that people who rarely experience regret, are also focused on how to do it better next time, but that they do not readily link the experience of regret to cognitive reflection and learning. Thus, special methods might have to be developed to trace this link.

Finally, another limitation is the lack of informant reports, as all measures were self-reported. Self-report measures are superior in assessing constructs related to emotions and affect, such as regret and life satisfaction, but they are less optimal for assessing traits that are high in observability and evaluativeness (Hofstee, 1994; Vazire, 2010). Caution is thus warranted as underreporting or reporter bias may have affected our findings. Furthermore, we asked participants to indicate their regret over a set of common behaviors, but we did not ask how often the behavior itself took place. For our regret frequency measure this may actually not be so problematic, as we included many behaviors that are so common that most people experience them on a daily basis (e.g., most people have to get out of bed every morning). Those with poor self-regulatory abilities may experience more problems with these daily activities and hence report also more regret. Relatedly, in future research it would be recommended to assess the daily dynamics of regret via experience sampling to reduce recall bias and measure our constructs more ‘in the moment’ (see also Bjälkebring et al., 2016; Kahneman et al., 2004).

For future studies, it might be relevant to expand the breath of regret by also including counterfactual thinking without self-blame as well as moral emotions that are related to regret, such as guilt and shame (Warr, 2016; Zeelenberg et al., 1998), and how this is related to well-being. In doing so, we may be still better able to determine the conditions under which emotions like regret fail (or do not fail) to perform their positive self-regulatory function, and how they are yoked to self-regulatory abilities.

Another avenue for future research concerns gaining more insight into the regulatory processes that are involved in everyday decision making (Västfjäll et al., 2011). Here, the question arises to what extent poor self-regulatory abilities are related to strategies when one anticipates regret and how this anticipation affects regret frequency. For example, people with poor self-regulatory abilities might experience more regret but anticipate it less. Alternatively, people may minimize regret, because they anticipate it (see Bjälkebring et al., 2016).

In sum, we revealed that the functionality of regret is not straightforward. When it comes to daily activities (i.e., activities that may be repeated) and their link to well-being, one should consider the tandem of impulsive antisociality and the emotions of regret, frequently experienced. The dynamics of this tandem says much about the preconditions of well-being and the importance of social aspects for learning from one’s mistakes and increasing one’s well-being.

Data Availability and Material

Data and instruments are available upon reasonable request from the first author.

Notes

Originally the subscale contains five items but two items have been removed because they directly refer to feeling depressed.

References

Baskin-Sommers, A., Stuppy-Sullivan, A. M., & Buckholtz, J. W. (2016). Psychopathic individuals exhibit but do not avoid regret during counterfactual decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 113, 14438–14443. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1609985113

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5, 323–370.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Dewall, C. N., & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 167–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307301033

Bjälkebring, P., Västfjäll, D., Svenson, O., & Slovic, P. (2016). Regulation of experienced and anticipated regret in daily decision making. Emotion, 16, 381–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039861

Bourgeois-Gironde, S. (2010). Regret and the rationality of choices. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1538), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0163

Breugelmans, S. M., Zeelenberg, M., Gilovich, T., Huang, W.-H., & Shani, Y. (2014). Generality and cultural variation in the experience of regret. Emotion, 14, 1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038221

Broomhall, A. G., Phillips, W. J., Hine, D. J., & Loi, N. M. (2017). Upward counterfactual thinking and depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.010

Buchanan, J., Summerville, A., Lehmann, J., & Reb, J. (2016). The Regret Elements Scale: Distinguishing the affective and cognitive components of regret. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(3), 275–286.

Cooper, A., & Gomez, R. (2008). The development of a short form of the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire. Journal of Individual Differences, 29, 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001.29.2.90

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Elliot, A. J., Thrash, T. M., & Kou Murayama, K. (2011). A Longitudinal analysis of self-regulation and well-being: avoidance personal goals, avoidance coping, stress generation, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 79(3), 643–674.

Epstude, K., & Roese, N. J. (2008). The functional theory of counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308316091

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Gilovich, T., & Medvec, V. H. (1995). The experience of regret: What, when, and why. Psychological Review, 102, 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.379

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85, 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Hofstee, W. K. B. (1994). Who should own the definition of personality? European Journal of Personality, 8, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410080302

Inman, J. J. (2007). Regret regulation: Disentangling self-reproach from learning. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1701_4

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science, 306, 1776–1780.

Komiya, A., Oishi, S., & Lee, M. (2016). The rural–urban difference in interpersonal regret. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216636623

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2007). Whatever happened to “What might have been”? Regrets, happiness, and maturity. American Psychologist, 62, 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.7.625

Lecci, L., Okun, M. A., & Karoly, P. (1994). Life regrets and current goals as predictors of psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.731

Lindenberg, S. (2013). Social rationality, self-regulation and well-being: The regulatory significance of needs, goals, and the self. In R. Wittek, T. A. B. Snijders, & V. Nee (Eds.), Handbook of Rational Choice Social Research (pp. 72–112). Stanford University Press.

Lindenberg, S. (2015). From individual rationality to socially embedded self-regulation. In R. Scott & S. Kosslyn (Eds.), Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences (pp. 1–15). John Wiley and Sons.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1982). Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. Economic Journal, 92, 805–824. https://doi.org/10.2307/2232669

Moore, K., & McElroy, J. C. (2012). The influence of personality on Facebook usage, wall postings, and regret. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.009

Newall, N. E., Chipperfield, J. G., Daniels, L. M., Hladkyj, S., & Perry, R. P. (2009). Regret in later life: Exploring relationships between regret frequency, secondary interpretive control beliefs, and health in older individuals. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 68, 261–288. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.68.4.a

Robinson, M. D. (2007). Gassing, braking, and self-regulating: Error self-regulation, well-being, and goal-related processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 1–16.

Roese, N. J. (2005). If only: How to turn regret into opportunity. Broadway Books.

Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 133–148.

Roese, N. J., Epstude, K., Fessel, F., Morrison, M., Smallman, R., Summerville, A., & Segerstrom, S. (2009). Repetitive regret, depression, and anxiety: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.6.671

Roese, N. J., & Summerville, A. (2005). What we regret most and why. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1273–1285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205274693

Rude, S. S., Maestas, K. L., & Neff, K. (2007). Paying attention to distress: What’s wrong with rumination? Cognition and Emotion, 21, 843–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930601056732

Saffrey, C., Summerville, A., & Roese, N. J. (2008). Praise for regret: People value regret above other negative emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 32, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9082-4

Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1178–1197. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1178

Steverink, N., Lindenberg, S., Spiegel, T., & Nieboer, A. P. (2020). The associations of different social needs with psychological strengths and subjective well-being: An empirical investigation based on social production function theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(3), 799–824.

Summerville, A. (2011). The rush of regret: A longitudinal analysis of naturalistic regrets. Social Psychological and Personality Bulletin, 2, 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611405072

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72, 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

Thomsen, D. K., Tønnesvang, J., Schnieber, A., & Olesen, M. H. (2011). Do people ruminate because they haven’t digested their goals? The relations of rumination and reflection to goal internalization and ambivalence. Motivation and Emotion, 35, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9209-x

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561

Valshtein, T. J., & Seta, C. E. (2019). Behavior-goal consistency and the role of anticipated and retrospective regret in self-regulation. Motivation Science, 5, 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000101

Vazire, S. (2010). Who knows what about a person? the self–other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017908

Västfjäll, D., Peters, E., & Bjälkebring, P. (2011). The experience and regulation of regret across the adult life span. In I. Nykliček, A. Vingerhoets, & M. Zeelenberg (Eds.), Emotion regulation and well-being (pp. 165–180). Springer.

Warr, M. (2016). Crime and regret. Emotion Review, 8, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073915586818

Wit, E. A., Donnellan, M. B., & Blonigen, D. M. (2009). Using existing self-report inventories to measure the psychopathic personality traits of Fearless Dominance and Impulsive Antisociality. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 1006–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.06.010

Zeelenberg, M. (1999). The use of crying over spilled milk: A note on the rationality and functionality of regret. Philosophical Psychology, 13, 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/095150899105800

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1701_3

Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W. W., Van der Pligt, J., Manstead, A. S. R., Van Empelen, P., & Reinderman, D. (1998). Emotional reactions to the outcomes of decisions: The role of counterfactual thought in the experience of regret and disappointment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75, 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402781

Acknowledgements

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Tilburg University B (April, 2018/No. EC-2015.38a3t).

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JS and SM and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and added sections to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Code availability

Syntaxes are available upon reasonable request from the first author.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sijtsema, J.J., Zeelenberg, M. & Lindenberg, S.M. Regret, Self-regulatory Abilities, and Well-Being: Their Intricate Relationships. J Happiness Stud 23, 1189–1214 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00446-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00446-6