Nothing is enough for the man to

whom enough is too little.

Epicurus.

Abstract

The paper suggests a happiness technology in which income, and personal values and philosophy of life (PVPL) serve as means of happiness production. We offer a theoretical model predicting that people who underinvest in acquiring PVPL will have greater income but produce less happiness. We also present empirical evidence, obtained by analyzing survey results from 980 salaried employees aged 25-64, confirming that the association between income and subjective well-being is relatively small. We find that PVPL, as measured by materialistic values, maximization tendency, and income satisfaction, is an important predictor of personal happiness even when controlling for socio-demographic factors and health status. In addition, we show that the components of PVPL are not strongly correlated among themselves or with income, implying that each one makes an important contribution to happiness given the same amount of money.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Fowers (2010, p.106) argue that instrumental rationality has five characteristics, among them: strict separation between means and ends in human activity; means that are constructed as strategies, tools or techniques; and assessment of the desired outcome on the basis of criteria such as effectiveness of the means.

Other Greek philosophers argued, “Being contented with the minimum required for living brings the ‘liberty’ of not being a slave to external goods – another way of being rich, in that one has what is needed” (quoted in Vivenza 2007, p. 13). Also, the Roman philosopher Seneca claimed, “the happy man is content with his present lot, no matter what it is”, (Quoted in McMahon 2006, p. 55)..

Note that the philosopher Adam Smith was aware that thinking that wealth, social recognition and fortune leads to happiness is a deception (Bruni, 2004).

We drew the isoquant curve as convex because we assume decreasing marginal productivity.

Marquis de Condorcet..

The mapping from \(T_{\alpha } \le \bar{T}\) to \((T_{p}^{*} ,T_{s}^{*} )\) can be calculated in the manner demonstrated in Fig. 1 using all \(\bar{T}^{\prime } \le \bar{T}\).

The original scale included 10 items. When examined the validity of this construct by means of CFA, we removed items with low factor loadings; only 6 items remained..

The original scale included 7 items. We examined the validity of this construct using CFA, and removed the items with low factor loadings; only 4 items remained.

The options were: (1) 8 years, (2) 9-10 years, (3) 11-12 years, (4) Some high school, (5) High school graduate, (6) Some nonacademic training, (7) Competed non-academic training, (8) Studying for bachelor’s degree, (9) Bachelor’s degree, (10) Studying for master’s degree, (11) Master’s degree graduate, (12) Studying for doctorate, (13) Doctorate..

Individual income was chosen, consistent with the model described in Sect. 2. We also asked about household income, and the regression results (presented in Sect. 3) were similar with both income variables. Based on the Social Survey 2017, administered by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, there were 10 possible answers, in New Israeli Shekels (NIS). (1) Less than 2000; (2) 2001-3000; (3) 3001-4000, (4) 4001-5000, (5) 5001-6000; (6) 6001-7500; (7) 7501-10,000; (8) 10,001-14,000; (9) 14,001-21,000; (10) More than 21,000. The average and median income for salaried employees in Israel in 2017 were NIS 9700 and NIS 7030 respectively (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics 2017).

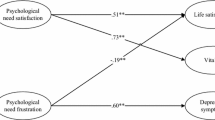

SEM is appropriate for this study for several reasons. First, SEM allowed us to control for a situation in which some predictors of the dependent variable are predicted by others. Second, SEM allows using Confirmatory Factor Analysis, which justified the structure of the constructs and demonstrated their good psychometric properties. Third, when capturing constructs based on multiple indicators, SEM identifies measurement errors, which facilitates depicting more accurate relationships between the constructs.

Sherman and Shavit (2017) report similar result when adding financial satisfaction to the regression.

References

Ackerman, N., & Paolucci, B. (1983). Objective and subjective income adequacy: Their relationship to perceived life quality measures. Social Indicators Research, 12(1), 25–48.

Ayalon, A. (2009). Midgam Project. http://www.midgam.com.

Bayer, P. J., Bernheim, B. D., & Scholz, J. K. (2009). The effects of financial education in the workplace: Evidence from a survey of employers. Economic Inquiry, 47(4), 605–624.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital. New York: Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bentham, J. (1789, [1996]). In J. H. Burns & H. L. A. Hart (Eds.), An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bergsma, A., Poot, G., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2008). Happiness in the garden of Epicurus. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 397–423.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. (2017). Unhappiness and pain in modern America: A review essay, and further evidence, on Carol Graham’s Happiness for All? (No. w24087). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bok, D. (2010). The politics of happiness: What government can learn from the new research on well-being. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bruni, L. (2004). The “technology of happiness” and the tradition of economic science. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 26(1), 19–44.

Cheek, N. N., & Schwartz, B. (2016). On the meaning and measurement of maximization. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(2), 126–146.

Clark, A. E., Flèche, S., Layard, R., Powdthavee, N., & Ward, G. (2018). The origins of happiness: The science of well-being over the life course. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dalal, D. K., Diab, D. L., Zhu, X. S., & Hwang, T. (2015). Understanding the construct of maximizing tendency: A theoretical and empirical evaluation. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 28, 437–450.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527.

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. (2010). Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(1), 52–61.

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 879.

Dolan, P. (2014). Happiness by design: Change what you do, not how you think. New York: Hudson Street Press.

Dolan, P. (2019). Happy ever after: Escaping the myth of the perfect life. London: Penguin Random House.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122.

Fowers, B. J. (2010). Instrumentalism and psychology: Beyond using and being used. Theory & Psychology, 20(1), 102–124.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435.

George, J. M., & Dane, E. (2016). Affect, emotion, and decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 136, 47–55.

Goodnick, B. (1977). Mental health from the Jewish standpoint. Journal of Religion and Health, 16(2), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01533152.

Graham, L., & Oswald, A. J. (2010). Hedonic capital, adaptation and resilience. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(2), 372–384.

Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (2017). Social Survey 2017. https://old.cbs.gov.il/publications19/seker_hevrati17_1761/pdf/qu_h.pdf.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lahav, E., Benzion, U., & Shavit, T. (2010). Subjective time discount rates among teenagers and adults: Evidence from Israel. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39, 458–465.

Larsen, J. T., & McKibban, A. R. (2008). Is happiness having what you want, wanting what you have, or both? Psychological Science, 19(4), 371–377.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. London: Penguin Books.

Layard, R. (2007). Happiness and the teaching of values. CentrePiece, 12(1), 18–23.

Leshem, D. (2016). Retrospectives: What did the Ancient Greeks mean by oikonomia? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(1), 225–238.

McMahon, D. M. (2006). Happiness: A history. New York: Grove Press.

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. Journal of Political Economy, 66(4), 281–302.

Norris, J. I., & Larsen, J. T. (2011). Wanting more than you have and its consequences for well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 877–885.

Noval, L. J. (2016). On the misguided pursuit of happiness and ethical decision making: The roles of focalism and the impact bias in unethical and selfish behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 133, 1–16.

Pigou, A. C. (1932). The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan.

Rasciute, S., & Downward, P. (2010). Health or happiness? What is the impact of physical activity on the individual? Kyklos, 63(2), 256–270.

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316.

Roets, A., Schwartz, B., & Guan, Y. (2012). The tyranny of choice: A cross-cultural investigation of maximizing-satisfising effects on well-being. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(6), 689–704.

Rubinstein, A. (2006). A sceptic’s comment on the study of economics. The Economic Journal, 116(510), c1–c9.

Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1178–1197.

Sherman, A., & Shavit, T. (2017). The thrill of creative effort at work: An empirical study on work, creative effort and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9910-x.

Sherman, A., Shavit, T., & Barokas, G. (2019). A dynamic model on happiness and exogenous wealth shock: The case of lottery winners. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(1), 1–21.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118.

Stigler, G. J., & Becker, G. S. (1977). De gustibus non est disputandum. The American Economic Review, 67(2), 76–90.

Tversky, A., & Shafir, E. (1992). Choice under conflict: The dynamics of deferred decision. Psychological Science, 3(6), 358–361.

Vivenza, G. (2007). Happiness, wealth and utility in ancient thought. In L. Bruni & P. L. Porta (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of happiness (pp. 3–23). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Weimann, J., Knabe, A., & Schöb, R. (2015). Measuring happiness: The economics of well-being. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study was supported by the Research Unit of the School of Business Administration at the College of Management Academic Studies, Israel.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sherman, A., Shavit, T., Barokas, G. et al. On the Role of Personal Values and Philosophy of Life in Happiness Technology. J Happiness Stud 22, 1055–1070 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00263-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00263-3