Abstract

After the Great Recession, a historically high level of foreclosures resulted in an accumulation of vacant properties in the USA. However, much of our recent knowledge about vacant housing has focused only on shrinking cities. Using multivariate analyses with vacancy data derived from the US Postal Service, this study examines patterns and factors associated with changes in neighborhood-level, long-term vacancies in three types of metropolitan areas across the nation during the US housing recovery from 2011 to 2014. The findings suggest that neighborhood factors associated with changes in long-term vacant homes vary based on the growth trajectory of metropolitan statistical areas (metros): In weak-growth metros, larger increases in long-term vacancies tended to occur in depressed neighborhoods with high shares of African Americans and single-family home renters. In hard-hit metros, which were hit by a large decline in home values, increasing levels of long-term vacancies were prevalent in neighborhoods with high levels of poverty and higher shares of townhomes and condominiums. Finally, in strong-growth metros, increases in long-term vacancies tended to occur in outlying counties. When comparing one type of metropolitan area to another, researchers and policy makers must acknowledge the limitations of generalizing their findings. With a more thorough understanding of the variations in the neighborhood dynamics of the housing market, they will be more equipped to inform both housing policy and research.

Source: HUD-USPS Vacancy Data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although the HUD-USPS database has been audited and maintained at an accuracy level of above 95%, a primary difficulty is accurately determining whether the property is truly vacant because vacancy counts primarily depend on reports by individual postal carriers. Because the USPS defines vacancy as an unoccupied address where mail has not been deliverable for 90 days or longer, the data are not captured immediately, nor do they contain the shortest term vacancies (GAO 2011). They also contain no details about the structure of the associated buildings.

The HUD-USPS data also provide counts of what the USPS calls “no stat” addresses, which include some long-term vacant properties that are not classified as vacant because they are not viewed as habitable. While in some instances these properties might be viewed as very long-term vacancies, the data on these units are extremely noisy and include partially constructed units and other unusual addresses. These data also vary widely across different regions and may induce substantial measurement error. In a telephone conversation, HUD staff involved in compiling the data recommended against using no-stat addresses in studies of long-term residential vacancy.

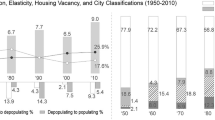

Although some metros have been losing population since the 1960s and 1970s, this study used the 10-year time span from 2005 to 2014 as a relatively long-time period because this study wanted to see the relationship between the recent housing crisis and changes in the vacancy rate. Population change and GDP per capita are common measures of metropolitan growth and economic development (Mollenkof 2008). Based on economic theory, changes in home values are used because they reflect the relative balance between housing market supply and demand and are likely to be predictors of overall vacancy rates. Moreover, the recent housing crisis represents the housing boom-bust, and changes in home values could extract the metros hit hardest from other strong and weak metros during the economic recession (Immergluck 2010a). Both longer and shorter term population change variables are used because the vacancy rate may be susceptible to such changes in various ways. In particular, longer term population increases are more likely to allow for housing supply responses to catch up with new housing market demand. Short-term population changes are added to assign more weight to population growth because shrinking cities tend to be those experiencing population decline in the short term (Pallagst 2009; Comen et al. 2017) together with long-term changes (Shilling and Logan 2008).

The value of the Silhouette measure of cohesion and separation is 0.55, which confirms that clusters are distinctive and meaningful groups (Norusis 2011), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) results show that the three clusters exhibit significantly different means among the four clustering variables.

Metros with high long-term vacancy rates in 2014 include Detroit (6.46%), Memphis (5.81%), Cleveland (5.18%), and Cincinnati (4.75%), and those with low long-term vacancy rates include San Jose (0.61%), San Francisco (1.16%), and Washington (1.18%).

Metros with the greatest decreases in long-term vacancy rates (2011–2014) include Jacksonville (− 42.8%), San Jose (− 42.5%), and San Francisco (− 27.3%); metros with the greatest increase in long-term vacancy rates (2011–2014) include Providence (31.2%), Baltimore (14.4%), and Detroit (7.2%).

Moran I and the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) tests of model specification are statistically significant at a 1% significance level.

Estimation results, not shown here, indicate that the model fit improved when the general spatial model was used, as indicated by an increase in the log likelihood as well as a decrease in Akaike’s information criterion (AIC).

Since the surge in vacancies began to decline after peaking in mid-2011 (Immergluck 2016), when the national housing recovery generally began, this study used 2011 as the beginning year for regression analyses to examine the neighborhood characteristics associated with changes in vacancies.

To formulate the independent variables in this study, this study used data from the 2008–2012 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year census tract estimates, which contain various demographic and housing characteristics at the census-tract level.

References

Accordino, J., & Johnson, G. T. (2000). Addressing the vacant and abandoned property problem. Journal of Urban Affairs, 22(3), 301–315.

Anselin, L. (1988). A test for spatial autocorrelation in seemingly unrelated regressions. Economics Letters, 28, 335–341.

Beauregard, R. A. (2006). When America became suburban. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Bobo, L., & Zubrinksy, C. L. (1996). Attitudes on residential integration: Perceived status differences, mere in-group preference, or racial prejudice? Social Forces, 74(3), 883–909.

Bowman, A. O. M., & Pagano, M. A. (2004). Terra incognita: Vacant land and urban strategies. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Brueckner, J., & Rosenthal, S. (2009). Gentrification and neighborhood housing cycles: Will America’s future downtowns be rich? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(4), 725–743.

Comen, E., Sauter, M. B., Stebbins, S. Frohlich, T. C. (2017). Americas fastest shrinking cities. Retrieved 2018 from https://247wallst.com/special-report/2017/03/23/americas-fastest-shrinking-cities-4/.

Cui, L., & Walsh, R. (2015). Foreclosure, vacancy and crime. Journal of Urban Economics, 87, 72–84.

Cumming, G., & Finch, S. (2005). Inference by eye: Confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist, 60, 170–180.

Glaeser, E., & Gyourko, J. (2005). Urban decline and durable housing. Journal of Political Economy, 113(2), 345–375.

Griswold, N., & Norris, P. (2007). Economic impacts of residential property abandonment and the Genesee County land bank in Flint, Michigan. Flint, MI: The MSU Land Policy Institute.

Han, H.-S. (2014). The impact of abandoned properties on nearby housing prices. Housing Policy Debate, 24, 311–334.

Haughey, R. M. (2001). Urban infill housing: Myth and fact. Washington, DC: The Urban Land Institute.

Hepp, S. (2013). Foreclosure and metropolitan spatial structure: Establishing the connection. Housing Policy Debate, 23(3), 497–520.

Hollander, J. (2011). Sunburnt cities: The great recession, depopulation and urban planning in the American Sunbelt. London: Routledge.

Ihlanfeldt, K., & Sjoquist, D. L. (1998). The spatial mismatch hypothesis: A review of the recent studies and their implications for welfare reform. Housing Policy Debate, 9(4), 849–892.

Immergluck, D. (2010a). Neighborhoods in the wake of the debacle: Intrametropolitan patterns of foreclosed properties. Urban Affairs Review, 46, 3–36.

Immergluck, D. (2010b). The accumulation of lender-owned homes during the US mortgage crisis: Examining metropolitan REO inventories. Housing Policy Debate, 20(4), 619–645.

Immergluck, D. (2016). Examining changes in long-term neighborhood housing vacancy during the 2011 to 2014 US national recovery. Journal of Urban Affairs, 38(5), 607–622.

Kain, J. (1985). Black suburbanization in the eighties: A new beginning. In J. M. Quigley & D. L. Rubinfeld (Eds.), American domestic priorities: An economic appraisal (p. 1991). Berkley: University of California.

Lee, C. A. (2018). Heterogeneity in income: Effects of racial concentration on foreclosures in Los Angeles, California. Housing Policy Debate. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1494026.

LeSage, J. (1998). Spatial econometrics. Toledo: Department of Economics, University of Toledo.

Logan, J., & Moloch, D. (1987). Urban fortune: The political economy of place. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mallach, A. (2006). Bringing buildings back: From abandoned properties to community assets. Montclair, NJ: National Housing Institute.

Mallach, A. (2017). What we talk about when we talk about shrinking cities: The ambiguity of discourse and policy response in the United States. Cities, 69, 109–115.

Mallach, A., & Brachman, L. (2010). Ohio’s cities at a turning point: Finding the way forward. Brookings, SD: Metropolitan Policy Program.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1998). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mollenkof, J. (2008). A fragile giant? The future of New York in an age of uncertainty prepared for panel 49 regional resilience: What can be done about it? University of California, Working paper 2008-08.

Myers, D. (1991). Housing markets: Linking demographic structure and housing markets. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Nassauer, J. I., & Raskin, J. (2014). Urban vacancy and land use legacies: A frontier for urban ecological research, design, and planning. Landscape and Urban Planning, 125, 245–253.

Newman, G., Bowman, A., Lee, R., & Kim, B. (2016a). A current inventory of vacant urban land in America. Journal of Urban Design, 21(3), 302–319.

Newman, G., Gu, D., Kim, J.-H., Bowman, A., & Li, W. (2016b). Elasticity and urban vacancy: a longitudinal comparison of US cities. Cities, 58, 143–151.

Newman, G., & Kim, B. (2017). Urban Shrapnel: Spatial distribution of non-productive space in a growing city. Landscape Research, 42(7), 699–715.

Norusis, M. (2011). IBM SPSS statistics 19 guide to data analysis. Boston: Addison Wesley.

Pallagst, K. (2009). Shrinking cities in the United States of America: Three cases, three planning stories. Retrieved September 2018 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=3972E70D0558F0A5996168C1576C53EE?doi=10.1.1.469.1050&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Payton, M. E., Greenstone, M. H., & Schenker, N. (2003). Overlapping confidence intervals or standard error intervals: What do they mean in terms of statistical significance? Journal of Insect Science, 3(34), 1–6.

Radzimski, A. (2016). Changing policy responses to shrinkage: The case of dealing with housing vacancies in Eastern Germany. Cities, 50, 197–205.

Raleigh, E., & Galster, G. (2014). Neighborhood disinvestment, abandonment, and crime dynamics. Journal of Urban Affairs, 37(4), 367–396.

Rosenthal, S. (2008). Old homes, externalities, and poor neighborhoods: A model of urban decline and renewal. Journal of Urban Economics, 63, 816–840.

Schuetz, J., Spader, J., & Cortes, A. (2016). Have distressed neighborhoods recovered? Evidence from the neighborhood stabilization program. Journal of Housing Economics, 60, 73–84.

Shilling, J., & Logan, J. (2008). Greening the Rest Belt: A green infrastructure model for right sizing America’s shrinking cities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74(4), 451–466.

Silverman, R. M. (2018). Rethinking shrinking cities: Peripheral dual cities have arrived. Journal of Urban Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1448226.

Silverman, R. M., Yin, L., & Patterson, K. L. (2013). Dawn of the dead city: An exploratory analysis of vacant addresses in Buffalo, NY 2008–2010. Journal of Urban Affairs, 35(2), 131–152.

Spelman, W. (1993). Abandoned buildings: Magnets for crime? Journal of Criminal Justice, 21(5), 481–495.

Sternlieb, G., & Indik, B. (1969). Housing vacancy analysis. Land Economics, 45, 117–121.

Tobler, W. (1970). A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Economic Geography, 46, 234–240.

US Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2016). HUD aggregated USPS administrative data on address vacancies. Retrieved May 16, 2016, from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/usps.html.

US Government Accountability Office. (2011). Vacant properties: Growing number increases communities’ costs and challenges. GAO-12-34. November.

Wang, K. (2018a). Housing market resilience: Neighborhood and metropolitan factors explaining resilience before and after the US housing crisis. Urban Studies,. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018800435.

Wang, K. (2018b). Neighborhood housing resilience: Examining changes in foreclosed homes during the US housing recovery. Housing Policy Debate. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1515098.

Wang, K., & Immergluck, D. (2018). The geography of vacant housing and neighborhood health disparities after the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Cityscape: A Journal of Housing and Urban Development, 20(2), 139–164.

Whilhelmsson, M., Andersson, R., & Klingborg, K. (2011). Rent control and vacancies in Sweden. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 4(2), 105–129.

Whitaker, S., & Fitzpatrick, T. (2013). Deconstructing distressed-property spillovers: The effects of vacant, tax-delinquent, and foreclosed properties in housing submarkets. Journal of Housing Economics, 22(2), 79–91.

Yin, L., & Silverman, R. M. (2015). Housing abandonment and demolition: Exploring the use of micro-level and multi-year models. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 4, 1184–1200.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Immergluck, D. Housing vacancy and urban growth: explaining changes in long-term vacancy after the US foreclosure crisis. J Hous and the Built Environ 34, 511–532 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9636-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9636-z