Abstract

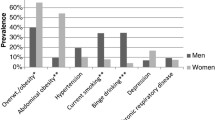

West Side Alive (WSA) is a partnership among pastors, church members and health researchers with the goal of improving health in the churches and surrounding community in the West Side of Chicago, a highly segregated African American area of Chicago with high rates of premature mortality and social disadvantage. To inform health intervention development, WSA conducted a series of health screenings that took place in seven partner churches. Key measures included social determinants of health and healthcare access, depression and PTSD screeners, and measurement of cardiometabolic risk factors, including blood pressure, weight, cholesterol and hemoglobin A1C (A1C). A total of 1106 adults were screened, consisting of WSA church members (n = 687), members of the local community served by the church (n = 339) and 80 individuals with unknown church status. Mean age was 52.8 years, 57% were female, and 67% reported at least one social risk factor (e.g. food insecurity). Almost all participants had at least one cardiovascular risk factor (92%), including 50% with obesity, 79% with elevated blood pressure and 65% with elevated A1C. A third of participants experienced ≥ 4 potentially traumatic events and 26% screened positive for depression and/or post-traumatic stress disorder. Participants were given personalized health reports and referred to services as needed. Information from the screenings will be used to inform the design of interventions targeting the West Side community and delivered in partnership with the churches. Sharing these results helped mobilize community members to improve their own health and the health of their community.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sampson, R. J., & Wilson, W. J. (1995). Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality. Race, Crime, and Justice: A Reader,1995, 37–56.

Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (2001). Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports,116(5), 404–416.

Williams, D. R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N. B. (2016). Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology,35(4), 407.

Kershaw, K. N., & Pender, A. E. (2016). Racial/ethnic residential segregation, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Current Diabetes Reports,16(11), 108.

Mehra, R., Boyd, L. M., & Ickovics, J. R. (2017). Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine,191, 237–250.

Simons, R. L., Lei, M.-K., Beach, S. R., et al. (2018). Discrimination, segregation, and chronic inflammation: Testing the weathering explanation for the poor health of Black Americans. Developmental Psychology,54(10), 1993.

Hunt, B., & Whitman, S. (2015). Black: White health disparities in the United States and Chicago: 1990–2010. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities,2(1), 93–100.

Orsi, J. M., Margellos-Anast, H., & Whitman, S. (2010). Black–white health disparities in the United States and Chicago: A 15-year progress analysis. American Journal of Public Health,100(2), 349–356.

Hunt, B. R., Tran, G., & Whitman, S. (2015). Life expectancy varies in local communities in Chicago: Racial and spatial disparities and correlates. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities,2(4), 425–433.

Breslau, J., Han, B., Stein, B. D., Burns, R. M., & Yu, H. (2018). Did the affordable care act’s dependent coverage expansion affect race/ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage? Health Services Research,53(2), 1286–1298.

Mechanic, D. (2002). Disadvantage, inequality, and social policy. Health Affairs,21(2), 48–59.

Williams, D. R., & Purdie-Vaughns, V. (2016). Needed interventions to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law,41(4), 627–651.

Wallerstein, N. B., & Duran, B. (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice,7(3), 312–323.

Dircksen, J., Prachand, N., et al. (2016). Healthy Chicago 2.0: Partnering to improve health equity, March, Chicago

Chaves, M., & Tsitsos, W. (2001). Congregations and social services: What they do, how they do it, and with whom. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,30(4), 660–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764001304003.

Hare, K. (2016). West side churches: Praise the lord! Chicago Defender,24, 2016.

Lynch, E. B., Emery-Tiburcio, E., Dugan, S., et al. (in press). Results of ALIVE: A faith-based pilot intervention to improve diet among African American church members. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action.

Anderson, E. E. (2011). CIRTification: Community involvement in research training facilitator manual. Center for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Illinois at Chicago. http://www.ccts.uic.edu/content/cirtification.

Blackwell, D. L., Lucas, J. W., & Clarke, T. C. (2014). Summary health statistics for US adults: National health interview survey, 2012. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey,260, 1–161.

Cohen, J. B., Wong, T. C., Alpert, B. S., & Townsend, R. R. (2017). Assessing the accuracy of the OMRON HEM-907XL oscillometric blood pressure measurement device in patients with nondialytic chronic kidney disease. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension,19(3), 296–302.

Pickering, T. G., Hall, J. E., Appel, L. J., et al. (2005). Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: A statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation,111(5), 697–716.

Ostchega, Y., Nwankwo, T., Sorlie, P. D., Wolz, M., & Zipf, G. (2010). Assessing the validity of the omron HEM-907XL oscillometric blood pressure measurement device in a national survey environment. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension,12(1), 22–28.

Ostchega, Y., Zhang, G., Sorlie, P., et al. (2012). Blood pressure randomized methodology study comparing automatic oscillometric and mercury sphygmomanometer devices. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2010, Citeseer.

Ostchega, Y., Nwankwo, T., Zhang, G., & Chiappa, M. (2016). Blood pressure cuff comparability study. Blood Pressure Monitoring,21(6), 345–351.

Paknikar, S., Sarmah, R., Sivaganeshan, L., et al. (2016). Long-term performance of point-of-care hemoglobin A1c assays. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology,10(6), 1308–1315.

Plüddemann, A., Thompson, M., Price, C. P., Wolstenholme, J., & Heneghan, C. (2012). Point-of-care testing for the analysis of lipid panels: Primary care diagnostic technology update. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners,62(596), e224–e226.

Guralnik, J. M., Simonsick, E. M., Ferrucci, L., et al. (1994). A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology,49(2), M85–M94.

Al Kibria, G. M. (2019). Racial/ethnic disparities in prevalence, treatment and control of hypertension among US adults following application of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline. Preventive Medicine Reports, p. 100850

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes. Accessed June 22, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/diagnosed.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Age-adjusted prevalence of prediabetes among adults aged ≥ 18 years, United States, 2011–2014. Accessed June 22, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/appendix.html#tabs-2-5.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. African Americans and tobacco use. Accessed June 22, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/african-americans/index.htm.

Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders,114(1–3), 163–173.

Spottswood, M., Davydow, D. S., & Huang, H. (2017). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care: A systematic review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry,25(4), 159–169.

Godbolt, D., Vaghela, P., Burdette, A. M., & Hill, T. D. (2018). Religious attendance and body mass: An examination of variations by race and gender. Journal of Religion and Health,57, 2140–2152.

Gillum, R. F. (2006). Frequency of attendance at religious services and leisure-time physical activity in American women and men: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Annals of Behavioral Medicine,31(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3101_6.

Cunningham, S. A., Patel, S. A., Beckles, G. L., et al. (2018). County-level contextual factors associated with diabetes incidence in the United States. Annals of Epidemiology,28(1), 20–25.

Murray, C. J., Kulkarni, S. C., Michaud, C., et al. (2006). Eight Americas: Investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Medicine,3(9), e260.

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., & Colen, C. G. (2011). Excess black mortality in the United States and in selected black and white high-poverty areas, 1980–2000. American Journal of Public Health,101(4), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.195537.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health,96(5), 826–833.

Shah, S. N., Russo, E. T., Earl, T. R., & Kuo, T. (2014). Peer reviewed: Measuring and monitoring progress toward health equity: Local challenges for public health. Preventing Chronic Disease,11, E159.

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology,19(6):586.

Saelens, B. E., Sallis, J. F., Black, J. B., & Chen, D. (2003). Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. American Journal of Public Health,93(9):1552–1558.

Blumberg, S. J., Bialostosky, K., Hamilton, W. L., & Briefel, R. R. (1999). The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. American Journal of Public Health,89(8):1231–1234.

Gray, M. J., Litz, B. T., Hsu, J. L., & Lombardo, T. W. (2004). Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment,11(4):330–341.

Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., et al. (2016). The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine,31(10):1206–1211.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the pastors, church coordinators and churches that participated in this study: Kandice Jones and Hope Community Church, Pastor Steve Spiller, Catherine Banks and Greater Galilee Missionary Baptist (MB) Church, Pastor Marshall Hatch, Rochelle Sykes, Gigi Fuller and New Mount Pilgrim MB Church, Pastor Cy Fields, Jessica Hudnall, and New Landmark MB Church, Pastor Ira Acree, Patty Ringo and Greater St. John Bible Church, Pastor Floyd James, Sr., Precious James and Greater Rock MB Church, and Pastor Michael Bryant, Tamara Gear and Kedvale New Mt. Zion MB Church. Numerous volunteers from each church also helped conduct the health screenings. In addition, numerous volunteers and staff from Rush University Medical Center helped with the screenings, including Wil Mims, Serena Sylvestri, and Shelby Gilyard. Research reported in this publication was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R56HL135247. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would also like to thank Dr. David Ansell and Darlene Hightower and the Rush University Medical Center Department of Community Engagement for providing additional funding for this study. Funding was also provided by the Foglia Family Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lynch, E.B., Williams, J., Avery, E. et al. Partnering with Churches to Conduct a Wide-Scale Health Screening of an Urban, Segregated Community. J Community Health 45, 98–110 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00715-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00715-9