Abstract

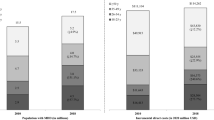

To describe the Medicaid costs associated with persons who are homeless or unstably housed. A retrospective secondary data analysis linked Medicaid recipient data with a statewide homeless management information system. A total of 19,950 persons received a housing service between 2012 and 2015 including 14,136 persons with Medicaid. Five of the most frequent diagnoses were substance abuse or mental health conditions in 42.83% of all diagnoses. The most frequent service was outpatient mental health and emergency department physician services. These costs totaled $166,653,689 with prescription drug costs at $62,800,463, with a total cost of $672,242,449, averaging $14,632.42 per 12-month period per person. The potential changes in Medicaid could lead to cost transfers or a reduction in services. Recognizing these are significant costs by homeless and unstably housed persons only, these high costs warrant the determination of points in care where effective cost saving interventions may be employed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blumenthal, D., Abrams, M., & Nuzum, R. (2015). The Affordable Care Act at 5 Years. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(25), 2451–2458.

Clemans-Cope, L., et al. (2013). The expansion of medicaid coverage under the ACA: Implications for health care access, Use, and spending for vulnerable low-income adults. Inquiry-the Journal of Health Care Organization Provision and Financing, 50(2), 135–149.

Lin, W.C., et al. (2015). Frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations among homeless people with medicaid: Implications for medicaid expansion. American Journal of Public Health, 105(Suppl 5), S716–22.

Tookes, H., et al. (2015). A cost analysis of hospitalizations for infections related to injection drug use at a county safety-net hospital in Miami, Florida. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0129360.

Fryling, L. R., Mazanec, P., & Rodriguez, R. M. (2015). Barriers to homeless persons acquiring health insurance through the affordable care act. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 49(5), 755–762, e2.

Larimer, M. E., et al. (2009). Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. Journal of American Medical Association, 301(13), 1349–1357.

Buchanan, D., et al. (2009). The health impact of supportive housing for HIV-positive homeless patients: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 99(Suppl 3), S675–80.

Hwang, S. W., et al. (2009). Multidimensional social support and the health of homeless individuals. Journal of Urban Health, 86(5), 791–803.

Hwang, S. W., et al. (2005). Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(4), 311–311.

Wolitski, R. J., et al. (2009). Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 14(3), 493–503.

Larimer, M. E., et al. (2009). Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA, 301(13), 1349–1357.

Fitzpatrick, K. M., M.E. La Gory, & Ritchey, F. J. (2003). Factors associated with health-compromising behavior among the homeless. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 14(1), 70–86.

Kertesz, S. G., et al. (2009). Rising inability to obtain needed health care among homeless persons in Birmingham, Alabama (1995–2005). Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(7), 841–847.

The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, U.S.D.o.H.a.U. Development, Editor. 2016, Housing and Urban Development: Washginton DC.

Peterson, R., et al. (2015). Identifying Homelessness among veterans using VA administrative data: Opportunities to expand detection criteria. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0132664.

Lancione, M. (2016). Beyond homelessness studies. European Journal of Homelessness, 10(3), 163–176.

Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, H.a.U. Development, Editor. 2016, Housing & Urban Development: Washginton DC.

van Santen, D. K., et al. (2016). Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs and the impact of the type of epidemic; extrapolating from Amsterdam, the Netherlands. PLoS ONE, 11(10), e0163488.

United States Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2011 (130th Edn.), 2010. Available from http://www.census.gov/statab/www/.

Palepu, A., et al. (2010). Addiction treatment and stable housing among a cohort of injection drug users. PLoS ONE, 5(7), 1–6.

Whittaker, E., et al. (2015). A place to call home: study protocol for a longitudinal, mixed methods evaluation of two housing first adaptations in Sydney, Australia. BMC Public Health, 15, 342.

Mason, K., et al. (2015). Beyond viral response: A prospective evaluation of a community-based, multi-disciplinary, peer-driven model of HCV treatment and support. International Journal on Drug Policy, 26(10), 1007–1013.

Patterson, M. L., et al. (2013). Trajectories of recovery among homeless adults with mental illness who participated in a randomised controlled trial of housing first: A longitudinal, narrative analysis. BMJ Open, 3(9), e003442.

Dickson-Gomez, J., et al. (2011). Access to housing subsidies, housing status, drug use and HIV risk among low-income U.S. urban residents. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6, 31.

Parker, R. D., & Dykema, S. (2014). Differences in risk behaviors, care utilization, and comorbidities in homeless persons based on HIV status. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 25(3), 214–223.

Parker, R. D., & Dykema, S. (2013). The reality of homeless mobility and implications for improving care. Journal of Community Health, 38(4), 685–689.

Kidder, D. P., et al. (2007). Access to housing as a structural intervention for homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV: Rationale, methods, and implementation of the housing and health study. AIDS and Behavior, 11(6 Suppl), 149–161.

Tsai, J., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2012). Outcomes of a group intensive peer-support model of case management for supported housing. Psychiatric Services, 63(12), 1186–1194.

Parker, R. D., & Albrecht, H. A. (2012). Barriers to care and service needs among chronically homeless persons in a housing first program. Professional Case Management, 17(6), 278–284.

Tsai, J., Mares, A. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2011). Housing satisfaction among chronically homeless adults: Identification of its major domains, changes over time, and relation to subjective well-being and functional outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(3), 255–263.

Rinke, M. L., et al. (2011). Operation care: A pilot case management intervention for frequent emergency medical system users. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 30(2), 352–357.

Mares, A. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2011). A Comparison of treatment outcomes among chronically homelessness adults receiving comprehensive housing and health care services versus usual local care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(6), 459–475.

Funding

This study was funded by State of West Virginia, Department of Commerce & Department of Health and Human Resources (no grant number provided).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parker, R.D., Cima, M.J., Brown, Z. et al. Expanded Medicaid Provides Access to Substance Use, Mental Health, and Physician Visits to Homeless and Precariously Housed Persons. J Community Health 43, 207–211 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0405-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0405-9