Abstract

Purpose

Coercive control is a power dynamic central to intimate partner violence (IPV) and consists of tactics to limit one’s partner’s autonomy through constraint, regulation of everyday life, isolation, pursuit, and intimidation and physical force. Such tactics may potentially signal a risk for future lethal or near lethal violence; hence, proper evaluation may enhance the utility of clinical femicide risk assessments. The goal of this study is to explore coercive control behaviors preceding partner femicides in Spain with the intention to provide guidance for its assessment by first responders and law enforcement.

Methods

Researchers from the Department of State for Security of the Ministry of Interior collected a nationally representative sample of 150 femicides (2006–2016). Qualitative data included 958 semi-structured interviews with victims and offenders’ social networks, which provided information about relationship dynamics leading up to the murders. Additionally, 225 interviews with law enforcement and occasionally offenders were used to corroborate and contextualize victim and offender social networks.

Results

Qualitative analysis indicated four indicators of coercive control (i.e., microregulation and restriction, victim isolation, surveillance and pursuit, and physical violence), which were present in 85% of the cases. While these indicators were commonly present, their manifestation varied based on relationship history and victims’ responses.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that incorporating coercive control indicia into clinical femicide risk assessments is useful and may enhance their accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Coercive control is a power dynamic entrenched in intimate partner violence (IPV) and comprises tactics to limit one’s partner’s autonomy through constraint, regulation of everyday life, isolation, manipulation, pursuit, and intimidation and physical force (Stark, 2007). Such tactics may be severe, injurious, and potentially signal a risk for future lethal or near lethal violence (Johnson, 2008; Myhill & Hohl, 2019). As a result, individualized evaluation of this dynamic may enhance the validity of femicide risk assessments (European Institute for Gender Equality, EIGE, 2019). This study aims to analyze 1) 958 in depth interviews conducted with victims and offenders’ social networks and 2) 225 additional interviews of law enforcement officers who investigated the homicides and occasionally the offenders as an effort to describe the patterns of coercive control observed prior to the femicides of 150 Spanish women (2006–2016). The ultimate goal is to offer guidance to facilitate the assessment of coercive control by first responders and law enforcement.

The authors will start with an overview of the Spanish context to situate IPV historically, allowing the reader to understand how coercive control is culturally pertinent to femicidal dynamics. Next, the authors present the universal challenges of preventing femicide from a risk management perspective and argue the utility of refining assessment of coercive control.

Historical Background

During the twentieth century, the history of Spain was tumultuous, including governmental instability, foreign wars, and a three-year civil war (1936–1939) that was followed by a 40-year dictatorship (1939–1975). During this period, the rights of women were severely restricted (i.e., no access to positions of power and legally forbidden to receive salaries, open bank accounts, or sign contracts without permission). Divorce was not legalized until 1981; women were “encouraged” to remain in their marriages regardless of their circumstances.

At best, the existing laws created a significant power differential between women and men, and at worst, facilitated the systematic subjugation of women through structural as well as interpersonally violent and non-violent means. This inequality was abundantly clear when partner violence cases came to the attention of the criminal justice system. Acts of physical violence were often ruled as misdemeanors, and femicides were considered “crimes of passion;” hence, less punishable.

In the early 2000’s, a series of gruesome femicides shook Spanish society to its core (see Sciolino, 2004), leading the Spanish government to approve the first partner violence law, the Organic Law 1/2004 of December 28th, 2004, of integral protective measures against gender violence. Despite its delay, this law became one of the most progressive of its kind in Europe. Consistent with coercive control theories, this law identifies the core of IPV to be the discrimination and subjugation of women, which allows for legal intervention in abuse cases without obvious physical violence. Second, it prescribes felony convictions for acts of physical violence against women as well as mandatory arrests and protective orders policies that aimed to substantially shorten the time women remain trapped in abusive relationships. Third, it provides the foundation for other initiatives, including specialized government agencies (i.e., Spanish Observatory on Domestic Violence), attorney general task forces, gender violence courts, and a new data system for nation-wide law enforcement coordination (i.e., Integral Monitoring System in Cases of Gender Violence—VioGén System) (González-Álvarez et al., 2018).

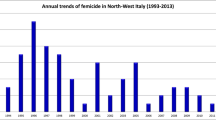

As a result of these systematic changes, instances of IPV have been increasingly reported and barriers for women to leave abusive relationships reduced (i.e., from 346 reports/day in 2007 to 457 reports/day in 2018) (Observatorio Estatal de Violencia sobre la Mujer, 2021). Nonetheless, the increase in reports of partner violence had not led to the expected drastic increase in capacity for preventing femicides. Between 43 and 70 women still die every year, adding up to a total of 1125 between 2003 and 2021 (Delegación de Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género, 2021). As a result, the Spanish Department of State (SDS) of the Ministry of Interior is developing a research initiative to enhance understanding of femicides and devise new or better prevention strategies. The current study is part of this larger initiative and specifically aims to assess whether patterns of coercive control are relevant to understand how partner femicides unfold.

Femicide Prevention Challenges: Risk Management and Coercive Control

Despite proliferation of law, polices, and community interventions to address IPV, multiple related challenges have hampered detection and prevention of femicides. These challenges are not unique to Spain since partner violence trends and policies coalesce across countries (see Corradi & Stöckl, 2014; Nevala, 2017; Stamatel, 2014). Many such initiatives are conducted at the legal (i.e., development and enforcement of new laws) and law enforcement levels (i.e., creation of new law enforcement victim protection protocols) (see Ellis, 2015). Their premise is that detecting victims with recurrent IPV and facilitating that they leave the violent relationship will curb the number of deaths (i.e., exposure reduction framework, Dugan, et al., 2003; Jaffe et al., 2013). This is a promising and successful victim management approach (see Koppa & Messing, 2021; Messing et al., 2022) that entails 1) identifying risk factors for femicide, 2) conducting risk assessments, and 3) implementing risk management plans tied to the victims’ sources of risk. Nonetheless, its effectiveness in preventing harm may be limited if coercive control is not properly assessed (Council of Europe, 2011; EIGE, 2019).

First, risk factors for lethal violence are often conflated with those that maintain chronic physical IPV based on the notion that physical abuse and femicide are different severity levels of the same phenomenon. We argue that this approach may hinder predictive validity. Though specific demographics tend to enhance the risk for IPV and femicide alike— low economic status (Campbell et al., 2003), unemployment (Wilson et al., 1995), as well as ethnic minority and immigrant status (Sabri et al., 2021; Soria-Verde et al., 2019)— such indicators are distal, broad, and may not be useful in individualized forensic predictions. More operationally relevant indicators are the events and behaviors precipitating femicide, but these are heterogenous and not necessarily linked to those that maintain chronic abuse, posing the question of whether recurrent physical IPV should be the dominant benchmark to identify femicidal risk (see Dobash et al., 2007; Matias et al., 2020; Taylor & Jasinski, 2011). Indeed, in their seminal work, Block and Block (1993) note that there were significant differences between abused women who were and were not killed by their spouses, and recent studies continue to support this finding and suggest that coercive control may be key discriminating between the groups (i.e., direct threats, pursuit, extreme microregulation, and threats with weapons) (Campbell et al., 2003, 2009; Echeburúa et al., 2009; Glass et al., 2008). As such, nuanced understanding of proximal risk factors of femicide, including coercive control, is required.

Second, risk assessment tools, which are key to the risk prediction approach and underpin most femicide prevention efforts (see Eke et al., 2011), rely on the combined predictive power of identified risk factors. This risk prediction approach may be problematic for femicides because of their low base rate (less than 1% of females per 100,000 habitants in Spain between 2010–2019, Eurostat, 2021), which precludes accurate mathematical prediction of their occurrences (see comments by Borum et al., 1999). Further, general risk prediction approaches often result in one-time assessments rather than continuous assessment of underlying and ongoing partner dynamics—a crucial element to understand patterns of partner abuse (exception of this is the Danger Assessment, Campbell et al., 2009).Footnote 1 Since the vast majority of femicides unfold along a trajectory of controlling and coercive dynamics that wax and wane and do not escalate in a linear manner (Felson & Massoglia, 2012; Gnisci & Pace, 2016; Kafonek et al., 2021; Sheehan et al., 2015), one-time risk prediction approaches may leave practitioners ill equipped to identify femicidal risk. Therefore, ongoing relationship indicators, especially those linked to coercive control, need to receive special consideration.

Third, challenges associated with risk prediction has led many countries like the US (e.g., Messing & Campbell, 2016) or Spain (López-Ossorio et al., 2021) to adopt risk management approaches that are conducted at the level of law enforcement. A risk management approach to prevent femicide may be preferable (to risk prediction approaches) because it does not focus on one-time predictions; rather the essence of risk management is to identify sources of risk, classify victims based on their current level of risk, and intervene-reassess ongoingly to protect them from any further harm (e.g., physical violence, stalking, femicide) (see Douglas & Kropp, 2002), which allows for better assessment of coercive controlling relationship transactions and femicidal trajectories. The problem is that proper guidance for assessment of coercive control during case triage is not readily available to law enforcement, the judiciary, and other first responders.

The Current Study

Considering all these complex challenges, the European Institute for Gender Equality (2019) advocates for including protocolized measurement of coercive control during police risk management practices to help identify victims at risk for femicide, referring them to other professionals when further exploration is needed. Incipient research on the paths from coercive control to femicide shows promise supporting this proposal (e.g., Myhill & Hohl, 2019). As such, the focus of the present study is to identify coercive control tactics as well as other related triggers precipitating femicide through the narratives of 958 individuals who were part of the victims and/or offenders’ networks and witnessed the relationship dynamics leading up to the femicide. In addition, 225 interviews law enforcement officers who investigated the femicides and the offenders were done to corroborate and contextualize victim and offender social networks’ reports. Reliable interviews of social networks have been found to be valid sources to gauge victims’ risk prior to their deaths (Campbell et al., 2003; Sheehan et al., 2015); thus, ensuring the best possible description of the victims’ situations within six months of their deaths.

Methods

Study Participants

The current study took place within a larger, national research initiative led by the National (research) Team of Detailed Reviews of Partner Homicide—hereafter called EHVdG following the Spanish abbreviation of its name— of the State Department of the Ministry of Interior (see González et al., 2018). The Spanish Ministry of Interior reviewed this study to ensured it followed the ethical and legal requirements for research with human beings, confidentiality, and data protection. Additionally, the Institutional Review Boards of all universities involved also certified that ethical requirements were followed in each data collection location.

Targeted participants of this study were 1183 witnesses of 150 femicides that had occurred in Spain between 2006 and 2016 (22.2% of all the femicides that occurred in the country during that period). Of these total number, 958 participants belonged to the victim and/or offender social networks (i.e., family members, friends, neighbors, coworkers). A total of 88.6% of cases included interviews of both the victim and the offender social network, less often cases included reports of either the victim (8.1%) or the offenders (1.6%) social circles. The current study focused on these 958 interviews. In addition to these participants, the data collection teams interviewed an additional 225 participants who included officers who investigated the femicides and the offenders. The data of these second types of reports was used for convergence purposes. Of all participants, 48.3% were men and 51.7% were women.

The recruitment of the study participants was done in collaboration with three government organizations in Spain, including the Attorney General’s Office for Crimes of Violence against Women, the General Council of the Judiciary, and the Government Delegation for Gender Violence. These government agencies first identified the femicide cases and the witnesses involved, and subsequently coordinated with four branches of law enforcement and correctional facilities from 28 provinces across Spain, which presented the research project to the potential participants. If the participants gave their consent, their contact details were passed onto the data collection researchers. The data collection researchers were faculty from the 21 universities and three research institutions across the country, who trained teams of two graduate students with a background in forensic psychology and familiarity with qualitative inquiry.

Data Collection

These teams of two students collected descriptive data of the victim and offender relationship status at the time of the murder as well as the demographic data of study participants. Next, they conducted semi-structured interviews of study participants that generally lasted between 45 min and 1 h and 30 min. Each interview was conducted in a private location of the participants’ choosing.

Interview questions were open-ended and encouraged sharing the experiences of the offenders and victims’ relationships prior to the murders, allowing the participants to define potential experiences of abuse in their own terms (e.g., behaviors of restriction, isolation, pursuit, physical and emotional abuse). A first set of questions aimed to obtain broad information on the relationship between victims and offenders (e.g., “How was the relationship between victim and offenders six months before the murders?” “What was the nature of the conflict between them?”). These questions were followed up with additional open-ended questions, so participants described the specific behaviors they have directly observed or heard firsthand from victims, offenders, or both. For example, if participants initially noted that offenders were “controlling”, the interviewers clarified the nature of such behavior first asking more open-ended questions (e.g., “What do you mean by controlling?”) and progressively clarifying what the participants meant by following up with more specific questions (e.g., “How did control entail a restriction of victims’ autonomy?” “When did control include surveillance?”). Those explanations allowed for gaining better understanding of the centrality of coercive control in victim and offender interactions prior to the murders. In addition, the interviewers assessed how precise participants were in their use of abusive terminology and offered clarification when needed to ensure the accuracy of the participants’ answers.

At the end of the interviews, all participants agreed to be re-contacted to clarify any aspect of their recollection and reports. All interviews were recorded and, after each of them, descriptive reports/memos were written, which allowed an opportunity for reflexivity and to compare the similarities and differences across sources. Faculty reviewed the interview transcriptions and reports/memos to ensure the integrity of the data collection process and coordinated with the local law enforcement, courts, corrections, and the EHVdG to resolve any potential question.

Data Analysis

First initial descriptive statistics were provided about victims, offenders, and the status of their relationship (i.e., length, termination status, and prior partner violence convictions). Next, the transcribed interview data were analyzed via directed content analysisFootnote 2 (see Crabtree & Miller, 1999; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), which was informed by preexisting theories and behavioral taxonomies of coercive control (Raghavan et al., 2019) that are present in Spanish national risk assessment initiatives (Valoración Policial del Riesgo – 4, VPR-4, López-Ossorio et al., 2016). Such definitions were the preliminary framework upon which the group of researchers of the EHVdG began to immerse themselves in the data, so they were used to create a priori coding scheme.

The initial coding grid of coercive control for content analysis was further validated by refining the a priori codes with further analysis of the types of behaviors, pervasiveness in victims’ life, and directionality of such behavior (i.e., latent pattern content analysis). After initial validation, the coding grid included four behaviors of coercive control that can be detected by third parties (i.e., micro-regulation and restriction, isolation, pursuit and surveillance, as well as intimidation and physical violence). The structure of the initial coding was refined iteratively as interviews were completed and subthemes of the four coercive control behaviors emerged. In addition, jealousy behaviors were added as indicators of coercive control since they appeared as the primordial grievance upon which other indicators of coercive control evolved (see Table 1). An example of how this process worked was as follows: researchers consensually operationalized “microregulation or restriction” with the condensed definition “behaviors used to restrict or regulate victim movement and autonomy”, to be consistent with the core of the description used in the Spanish risk assessment tools. Further assessment of such behavior included the framework to qualify such behavior, which included the theme types of the behavior (e.g., physically restrict victims’ autonomy so she cannot leave the house whenever she wants) and particular subthemes regarding to the directionality and pervasiveness of the behavior (e.g., offender resorts to this behavior daily while the victim never does).

Since the final coding categorization was further used in other studies to assess the different associations of coercive control with different aspects of victims and offenders’ characteristics, the qualitative exerts of each indicator of coercive control were also quantitatively coded (e.g., endorsement of a coercive control theme per case). The quantitative coding in this study is only used to indicate the frequency of each theme. An “audit trail” of changes in the codebook was kept as the coding and analysis progressed.

Reliability was assessed and addressed following the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) method (Hill et al., 1997), which incorporates elements from phenomenological, grounded theory, and comprehensive process analysis. This research method prescribes using a team consensus approach to systematically evaluate the reliability and ensure the best possible construction and interpretation of data. All interview transcripts were thoroughly analyzed, and key excerpts highlighted. The identified portions were coded into the identified coercive control themes by two field coders. Next, a group of four academic experts used the codebook to 1) independently review the coded documents to assess potential threats to validity that may arise from the initial coders’ personal bias and group-thinking processes and 2) reach consensus about the excerpts of each transcript that reflected coercive control indicators. An EHVdG researcher, who specialized in the study’s codebook and acted as an auditor, did a final review of interpretations made by initial coders and groups of experts. Trustworthiness and discrepancies among interviewees were resolved based on which topics were endorsed by the majority of the sources and were consistent with collateral records (i.e., triangulation, Fontana & Frey, 2005). Interviewees’ quotes are provided to demonstrate credibility of interpretations.

Results

Victim and Offender Sociodemographic

Perpetrators were all males aged 46 years old, on average (M = 46.4, SD = 14.6). Seventy percent were of Spanish provenance (70%, n = 105) and the remaining 30% (n = 45) were from other countries. The victims were all female aged 42 years old, on average (M = 41.5, SD = 14.7; Range 14 to 77). Most of them were Spanish nationals (68%, n = 102) and about a third (32%, n = 48) were foreigners. Court records suggested femicidal couples had been together for about 14 years, on average, (SD = 14.4 years). A slight majority (57.4%, n = 63) of the couples had terminated the relationship at the time of the murders and had been separated for about 8 months (M = 7.6 months, SD = 1 year and 7 months). Approximately one fourth of the offenders had been previously convicted for abusing the victim (23.3%, n = 35).

Coercive Control Six Months Before the Femicides

Qualitative data gathered through family members and close friends suggested that social networks had intimate knowledge of the offender-victim relationship. Witnesses indicated that coercive control behavior was present in at least 85.3% (n = 128) of the cases. Behaviors related to jealousy, microregulation and restriction, and physical violence were almost ubiquitous to the sample (> 70%), while victim isolation as well as surveillance and pursuit were less commonly detected (30%-40%). The following witnesses’ quotes offered different examples of how elements of coercive control evolved within six months of the murders.

Jealousy Driven Behaviors

Jealousy was a commonly reported theme. Witnesses in approximately 73% of the cases (72.7%, n = 109) described offenders whose jealous statements and behaviors often revolved around the presence of a potential threat to their relationship, as evidenced by this example:

“He showed me the pictures that she uploaded, the sentences that she wrote [in an online platform]. He already knew, even though no one had confirmed that to him, that she was with another person.”

Generally, those statements were followed by additional checking by the offender. For example, in the above case, an offender’s relative further described the offender’s attempts to verify his suspicions:

“While my brother [the offender] was still living there [with the victim], [the victim] went to a village for a few days, I do not know which village, one where a friend lived. She spent some days there. Then, when the relationship ended, my brother decided to speak with her [that friend], because he started to think that she [the victim] had not gone with her [friend] (she had gone with the allegedly new boyfriend). But yes, indeed, she had gone with her friend.”

While most jealous statements and behaviors occurred in situations where another relationship had begun or was about to begin, some statements occasionally reflected that the offenders held distorted jealous beliefs despite disconfirming evidence. For example, a victim’s relative indicated that the offender often justified his violent and coercive behavior to the victim under the suspicion that she was with another man. But that man was already dead:

“Excusing himself, and saying he was [a very good guy], that it was not him, [he] blamed another man who was already dead. He said that she was having [sexual] relationships with him, but it was all a lie. Everything was a product of his head.”

Microregulation and Restriction

Microregulation and restriction tactics were apparent to victims’ relatives or friends in about 75% of the cases (75.3%, n = 113). Most witnesses’ reports portrayed the offender as systematically using a combination of tactics to maintain power and deprive victims of their basic liberties (44%, n = 66 cases). These tactics started by capitalizing on traditional gender roles expectations of how men and women should operate in a relationship. For example, a victim’s relative noted that her sister’s eating schedule was contingent upon her partner’s desires, noting that, “my sister had to have lunch alone, because, until he did not eat the last remaining fry, my sister had to serve him.”

Once a particular expectation was set, offenders reportedly increased control to ensure ongoing adherence to established commitments and roles. For example, a victims’ relative noted that an offender often kept constant tabs on victim’s whereabouts, explaining that, “when she (the victim) occasionally came (to visit the relative) and such, [he] always [asked her], Where were you? What did you do? What about this? What about that?”.

Over time, such persistent micro-regulating and restricting tactics allowed the offender to hold the decision-making power and deny the victim any autonomy. For example, a victim’s mother spoke about how disempowered her daughter was prior to her death:

“She told me that that person (the offender) was very controlling, if for example [she] told [him] that she wanted to start working, ‘You? Why do you want to work?’ that was the answer that she gave me about what he was telling [her].”

In 16% of the cases (n = 24), witnesses’ statements suggested a different pattern where regulation and constraint tactics were situational; that is, they were not a pervasive part of life and surfaced in instances of recurring conflict and/or when trust was broken, especially over the course of the dissolution of the relationship. For example, a victim’s cousin explained that the offender had an erratic lifestyle and neglected the victim. His erratic behavior and overspending became unbearable, and the victim expressed a desire to separate. The offender then started to call her “ugly, old, and fat,” forbid her from visiting her friends, and forced entry into her (locked) bedroom to control her access to money. In another case, the daughter of the victim and the offender noted that her parents’ relationship was conflictive due to financial strains and that her mother “used to insult” her father; “she was the more violent… he never responded violently.” Eventually, her mother reportedly desired to separate and may have had another partner. “Everything started then,” the daughter noted, her father “looked constantly at her phone, the apps (phone applications), and regulated who she talked to or where she was.”

In about one tenth of the cases (9.3%, n = 14), witnesses noted that victims reportedly used similar controlling tactics as the offenders in attempts to regain power or provoke a reaction from their partner during conflict. For example, both the victims and offenders’ friends explained that the victim of a femicide used to completely regulate and mismanage household finances, while the offender started to regulate her access to the phone because he thought she had another lover. In another case, the offender’s mother explained that the victim used to constantly call her son asking him where he was, while he restricted the victim from vising her best friend.

In a small minority of cases, witnesses indicated that victims resorted to microregulation and restrictive tactics either occasionally (4.7%, n = 7) or systematically (3.3%, n = 5). Those atypical cases varied widely but generally included younger couples that struggled with addiction and life instability. For example, a friend living with the victim and the offender explained that the victim struggled with addiction, was “obsessed with the relationship,” and “jealous he had another girlfriend.” This witness proceeded to explain that she regulated who he could see.

Victim Isolation

A consequence of pervasive microregulation and restriction was that victims lost their autonomy and offenders manipulated them into limiting contact with their main sources of support. Such extreme pattern of isolation was reported in a third of the cases (33.3%, n = 50), with the offender exclusively using this tactic in most of these cases (30.7%, n = 46) (i.e., victims rarely attempted to limit offenders’ social circle). For example, a victim’s relative noted that the offender controlled the victim and severely limited the possibility to have contact with others:

“Every time that my sister came to [city name], [she] had a lot of problems… many. I always [asked] her what she was coming for to [city name] with him, because when she came to [city name], he did not allow her to see anyone.”

Witnesses also noted that victims were manipulated and/or coerced into remaining at home, often convincing them that isolating should be a sacrifice that women should do to maintain the relationship. For example, a witness noted that their friend (the victim) stopped socializing and remained at home and was unable to admit that the offender was convincing her that communication with others was detrimental for their relationship:

“It is true that when [the victim] met that guy [the offender], which I did not know until later, [she] did not go out with me either, she gave a lot of excuses, and I did not understand why, until I realized it was him behind it all. But she did not say that because she loved him, because they have been together for seven years. But she did not say this and that is what annoys me the most.”

According to witnesses’ reports, victims were rarely able to constrain offenders’ activities. Witnesses in three cases suggested that both victim and offenders (2%, n = 3) attempted to limit each other’s social circle, while only in one case (0.7%, n = 1) there was evidence that only the victim tried to control the offenders’ friendships.

Physical violence

Physical violence was also a commonly reported occurrence before the femicides (70.7%, n = 106). Witnesses’ statements suggested that offenders used force systematically for different reasons, including holding victims accountable to prior agreements, enhancing control, instilling fear, and regaining power (30%, n = 45 cases). For example, a victim’s friends described the extreme violence that a victim endured while dating the offender. She was from another country and married to an older Spanish man, who became physically violent “even when she was pregnant with their child.” According to the witness, her independence, ability to start a business, and attempts to leave the offender triggered physical assaults.

In a third of the cases, witnesses noted that violence was not systematically used and only occurred in the context of escalated arguments (i.e., situational). In these situations, generally one (15.3%, n = 23) or both partners (22%, n = 33) resorted to violence as means of conflict resolution. For example, the adult sons of the victim and offender of a case said they had never seen their father acting violently towards their mother. However, that had changed before the murder, they noted. Their father was obsessed with their mother sleeping with her boss, which both sons said was not the case. One day, the sons reportedly argued with their father about this but “he did not dare with [them] (to become violent), because [they] were not children anymore (so they could overpower him).” They continued to explain that, when they left the living room, they heard a hard slap and saw their mother with some redness on her face. That was the only act of physical violence of which they were ever aware. Prior to another femicide, a victims’ friend said that the victim and offender had a strong argument in her house where they “laid hands on each other.” Most events where victims and offenders pushed, shoved or slapped each other happened in the intimacy of their homes over the course of stressful situations and arguments.

According to the witnesses, victims of femicide infrequently engaged in violent behavior either systematically (0.7%, n = 1) or as a result of escalated arguments (2.7%, n = 4) (i.e., situational). When this occurred, violence took place during a state of intoxication and/or in public. For example, a law enforcement officer documented that the security personnel of a club observed a young woman assaulting her partner and presented obvious signs of alcohol intoxication. The victims’ friends noted this victim “was a strong woman” who did not hesitate to fight.

Surveillance and Pursuit

Approximately 40% of the witnesses recalled different episodes of surveillance and pursuit (40.7%, n = 61). In many of these cases (34%, n = 51), perpetrators pursued the victim using strategies that varied in severity and intrusiveness. Some reports suggested that the offenders initially attempted to coax the victim back into the relationship through pleas, but these attempts became exceedingly intrusive:

“I clarified one thing to [the victim]: that the relationship was over and now it is him [the offender] trying, by any means, to resume the relationship at all costs. And one thing is to allow some time to air [the relationship], to see if (him or her) indeed needs that (other) person (partner), and another thing is for the (offender) to take the phone and start sending [texts through WhatsApp], calling you every five minutes. That is not (just) concern.”

Intrusion into victims’ lives often came hand in hand with a combination of tactics that included the victims’ close network, as this victim’s relative described:

“That week or so, she was at a women’s shelter and came here (to the relative’s home) afterwards. In between, he (the offender) came to my house, crying, ‘[Name], you know where she is, please, talk to her, I want you to talk to her, I want to make peace (with her)’, and I do not know what else. For all of this (pleading for the victim to resume the relationship with him), [he] came here to cry (to the relative’s home).”

When these forms of pursuit and surveillance failed, offenders resorted to more intimidating tactics that would instill fear and aim to regaining control over the victims, sometimes with devastating consequences, as this victim’s relative explained:

“Yes, she was separated, and divorced by February… (since) she separated, (he) totally pursued her, and according to what (others) told me, my sister lost 20 kilos. According to what (third parties) told me, my sister lost 20 kilos, because he followed her, he insulted her there in the [City name], on the street.”

In a minority of cases, pursuit and harassment was performed by the victim (5.3%, n = 8) or by the victim and the offender (1.3%, n = 2), which often occurred in situations of high conflict with strong opposition from the victims to resist yielding power to the perpetrators.

Discussion

In response to a growing body of literature advocating for coercive control to be one of the foci of femicide prevention initiatives and law enforcement risk assessments (EIGE, 2019; Myhill & Hohl, 2019), this qualitative study explored coercive control preceding lethal violence and offers recommendations for its assessment.

The authors found that coercive control manifests in Spain as it does in other countries. It is a gendered dynamics used to entrap women in abusive relationships and make them compliant to the offenders’ desires (see Stark, 2007). Consistent with the results of other studies, such level of submissiveness was accomplished with the interplay of emotional manipulation and intense micro-regulation of victims’ everyday life (e.g., asking for personal sacrifices, dictating who the victim can see, regulating their cellphone use) (Raghavan et al., 2019). Surveillance was often used as a tool to ensure that women abide by offenders’ rules or to intimidate a victim who already left the relationship (Dutton & Goodman, 2005). Any attempt to breach offenders’ rules or limit that intense regulation was met with escalated attempts to curt victims’ autonomy (Crossman et al., 2016). As a result, women became entrapped by their abusers and operated in very controlled ways; however, they occasionally tried to resist in a desperate try to regain their autonomy, only to be constrained through force or intimidation (Stark, 2007; Williamson, 2010).

In the current study, these dynamics depleted victims’ autonomy and freedom, and likely hampered reporting the abuse to law enforcement (note: prior abuse was reported in less than 25% of the cases). However, families, friends, and witnesses’ reports clearly suggested that controlling and coercive transactions between victims and offenders were apparent (in 85% of the cases at least); consequently, femicides were not the “crimes of passion” that old Spanish legal approaches suggested. The implication of this result cannot be highlighted enough because it suggests that femicidal risk can be preemptively detected and reduced significantly but that even the most sophisticated femicide prevention initiatives will fail unless women at risk come forward and their risk is properly assessed.

These results offer some guidance to take the first steps for detection and assessment of coercive control within femicidal trajectories. The first step is to consider that future avenues for detection and assessment of women at risk may start by enhancing interagency cooperation and facilitating professionals across fields to perform thorough risk evaluations (e.g., family courts, unemployment and social services, primary care) (see Jaffe et al., 2013; Dugan et al., 2003). As we found, evaluators may consider speaking to victim networks— who are rarely interviewed— since these witnesses were able to provide insightful descriptions in cases where victims were unable or afraid to articulate their experiences.

The second step should be conducted at the broadest level. This step entails that, when assessing the paths of coercive control to lethal violence, evaluators may be best served by adopting a sequential, ongoing assessment model (see Gnisci & Pace, 2016; Kafonek et al., 2021; Sheehan et al., 2015). In doing so, a key consideration is that the assessment of prior physical violence should not be prioritized over exploration of clusters of victim restriction, isolation, and pursuit. There are two reasons for this. First, systematic physical violence was less common in our study than systematic regulation, restriction, surveillance, pursuit, and isolation, which offers continuing evidence that femicidal dynamics may not completely overlap with chronic physical abuse (Dobash et al., 2007; Nicolaidis et al., 2003; Taylor & Jasinski, 2011). Second, focusing on the combination of controlling and restrictive tactics makes visible patterns of abuse that traditionally hide in plain sight, helping uncover the real range of trajectories escalating into femicides.

The third step should occur at the more specific level. This step entails that, when assessing the different indicators of coercive control, evaluators may start by framing the assessment from the perspective that underlying grievances (i.e., jealousy, fear of abandonment, retribution) and violent ideation generally fuel subsequent behavior and mark the beginning of femicidal risk. We suggest the following considerations in doing so:

-

1.

Microregulation and restriction: Femicidal risk becomes clear when restriction and regulation of victims are all-encompassing and co-occur with other tactics. However, even when control is not all encompassing, evaluators should specifically assess if offenders in longstanding relationships simply have a reduced need of microregulation and restriction to entrap their partners, especially in cases where they are making use of their privileged knowledge of victims’ responses to past abuse (of any type) (Pomerantz et al., 2021). Such nuanced inquiry would enhance the evaluators’ scoring of already validated risk assessment tools, such as the VRP (López-Ossorio et al., 2016) in Spain and the Danger Assessment (Campbell et al., 2009) internationally, and bolster their predictive power.

-

2.

Isolation: The authors found victim isolation to particularly occur in situations of chronic abuse encompassing systematic restriction, microregulation of their everyday life, and physical violence. Chronic abuse is also consistently correlated with Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Woods, 2005), which may paralyze and further entrap women or simply overwhelmed women until they gave up asking for help. Thus, the evaluators need to skillfully assess how trauma affects victims’ responses to abuse.

-

3.

Physical violence: Obviously, systematic violence used to advance a grievance is clearly indicative of risk, especially in conjunction with other coercive control behaviors. But the authors found that, generally, violence was a situation-specific tactic to force women into desired behavior. In these situations, exploring the specific reasons for physical violence allows the assessor understanding better the extent of abuser manipulation and knowledge of victim vulnerabilities and the weight that physical violence really has in predicting lethality.

-

4.

Pursuit and surveillance: In addition to broadly asking the victims, “Were you pursued, followed, or stalked?”, evaluators should also inquire about specific manipulative tactics–sweet talking and threats to better understand the rejection-rage cycle and correspondingly, the risk to women.

As previously recommended (Douglas & Kropp, 2002), risk assessments should culminate in a management plan that should be organized around the elements mentioned above and reviewed periodically to note changes in risk presentation.

While an unusual and important study, several limitations are noted. First, this study’s data was collected retrospectively and through witnesses recalls; hence, it is likely that the totality of the coercive control activity preceding the murders was not captured. For example, instances of manipulation and sexual coercion, which frequently co-occur in coercive control dynamics were not reported by the participants of this study (see Raghavan et al., 2019), likely because these dynamics are not observable by third parties since they tend to occur in the intimacy of an intimate relationship. Second and relatedly, measurement of coercive control is generally extracted from victims’ reports (see Nicolaidis et al, 2003). However, this study relied on third parties’ accounts, which may have different ecological validity than that extracted from victim narratives. Further, such parties often had difficulty differentiating among different coercive control behaviors, for example, often intertwining regulation and restriction of victims’ activities. Third, this study relied on volunteering, which may have skewed the type of cases analyzed. Last, this study does not include a comparison group, which precludes the reader from assessing the differences between femicides and non-femicidal cases of coercive control.

Overall, this is among the first studies in Spain to contribute to understanding the processes of coercive control in this culture and advocate for the assessment of coercive control in various practice-oriented settings, especially those involving law enforcement and other first respondents, since nuanced evaluation of this dynamic will provide valuable information for femicide risk assessments. Likewise, screenings of violent or non-violent coercive control will offer some guidance into the women at risk’s needs and the appropriate resources for them. Since foreigner victims and offenders were overrepresented in this nationally representative sample, future studies should expand to account for intersection of race, culture (i.e., male power and cultural expectation of marriage), and social class within coercive control dynamics is warranted.

All these research findings and recommendations have important implications for the EHVdG’s current steps (see González-Álvarez et al., 2023): First, national risk assessment tools are being refined based on programmatic research results (e.g., development of a particular homicidal scale that is currently being tested, the VRP5.0 H-scale) (López-Osorio et al., 2021). Second, law enforcement protocols are being enhanced, and their effectiveness is currently evaluated (González-Prieto et al., 2023). Third, new national research initiatives are being conducted to compare femicidal and non-femicidal victims and uncover the reasons why women may not report partner violence— especially those from minority groups. The collective impact of this research is the bedrock upon which the Spanish government is building further legal and political initiatives to protect women as well as continuing to improve police practice.

Notes

Campbell’s Danger Assessment incorporates static risks (i.e., children from a different man) and also relevant relationship dynamic indicators of coercive behaviors, which occur ongoingly (i.e., increasingly jealous and controlling).

No data analysis software was used for the purpose of this study because each region had different resources and available software. In addition, Spain has five different official languages, which makes the use of a single software difficult. Some languages are not commonly available in commercial software. The EHVdG compensated for that limitation by ensuring all coding was done manually. They trained all the teams locally and consulted with all of them ongoingly as each team coded the interviews. An auditor ensured their coding followed the same rational despite regional differences.

References

Block, C. R., & Block, R. (1993). The Chicago homicide dataset. Questions and Answers in Lethal and Non-Lethal Violence, 1, 97–122.

Borum, R., Fein, R., Vossekuil, B., & Berglund, J. (1999). Threat assessment: Defining an approach for evaluating risk of targeted violence. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 17(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0798(199907/09)17:3%3c323::AID-BSL349%3e3.0.CO;2-G

Campbell, J. C., Webster, D. W., & Glass, N. (2009). The Danger Assessment: Validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(4), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317180

Campbell, J. C., Webster, D., Koziol-McLain, J., Block, C., Campbell, D., Curry, M. A., Gary, F., Glass, N., McFarlane, J., Sachs, C., Sharps, P., Ulrich, Y., Wilt, S. A., Manganello, J., Xu, X., Schollenberger, J., Frye, V., & Laughon, K. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. American journal of public health, 93(7), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089

Corradi, C., & Stöckl, H. (2014). Intimate partner homicide in 10 European countries: Statistical data and policy development in a cross-national perspective. European Journal of Criminology, 11(5), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370814539438

Council of Europe (CoE) (2011), Explanatory report to the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, CoE, Paris https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/council-of-europe-convention-on-preventing-and-combating-violence-against-women-and-domestic-violence

Crabtree, B., & Miller, W. (1999). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In B. Crabtree & W. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 163–177). Sage.

Crossman, K. A., Hardesty, J. L., & Raffaelli, M. (2016). “He could scare me without laying a hand on me”: Mothers’ experiences of nonviolent coercive control during marriage and after separation. Violence against Women, 22(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215604744

Delegación de Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género (2021, December 27). Ficha estadística de víctimas mortales por Violencia de Género. Año 2021. Ministerio de Igualdad, Gobierno de España. Retrieved February 20, 2022, from https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/victimasMortales/fichaMujeres/pdf/VMortales_2021_12_27.pdf

Dobash, R. E., Dobash, R. P., Cavanagh, K., & Medina-Ariza, J. (2007). Lethal and nonlethal violence against an intimate female partner: Comparing male murderers to nonlethal abusers. Violence against Women, 13(4), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207299204

Douglas, K. S., & Kropp, P. R. (2002). A prevention-based paradigm for violence risk assessment: Clinical and research applications. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 2, 617–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/009385402236735

Dugan, L., Nagin, D. S., & Rosenfeld, R. (2003). Exposure Reduction or Retaliation? The Effects of Domestic Violence Resources on Intimate-Partner Homicide. Law & Society Review, 37(1), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5893.3701005

Dutton, M. A., & Goodman, L. A. (2005). Coercion in Intimate Partner Violence: Toward a New Conceptualization. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 52(11–12), 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-4196-6

Echeburúa, E., Fernández-Montalvo, J., de Corral, P., & López-Goñi, J. J. (2009). Assessing risk markers in intimate partner femicide and severe violence: A new assessment instrument. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(6), 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508319370

Eke, A. W., Hilton, N. Z., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Houghton, R. E. (2011). Intimate partner homicide: Risk assessment and prospects for prediction. Journal of Family Violence, 26(3), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-010-9356-y

Ellis, D. (2015). The Family Court-Based Steppingstones Model of Triage: Some Concerns About Safety, Process, and Objectives. Family Court Review, 53(4), 650–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12178

Eurostat (2021). Intentional homicide victims by age and sex - number and rate for the relevant sex and age groups. Online data browser. Retrieved February 20, 2022, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/crim_hom_vage/default/table?lang=en

Felson, R. B., & Massoglia, M. (2012). When is violence planned? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(4), 753–774. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511423238

Fontana, A., & Frey, J. H. (2005). The Interview: From Neutral Stance to Political Involvement. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 695–727). Sage Publications Ltd.

Glass, N., Laughon, K., Rutto, C., Bevacqua, J., & Campbell, J. C. (2008). Young adult intimate partner femicide: An exploratory study. Homicide Studies: An Interdisciplinary & International Journal, 12(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767907313303

Gnisci, A., & Pace, A. (2016). Lethal domestic violence as a sequential process: Beyond the traditional regression approach to risk factors. Current Sociology, 64(7), 1108–1123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116629809

González, J. L., Garrido, M. J., López, J. J., Muñoz, J. M., Arribas, A., Carbajosa, P., & Ballano, E. (2018). Revisión Pormenorizada de Homicidios de Mujeres en las Relaciones de Pareja en España [In-depth review of intimate partner homicide against women in Spain]. Anuario De Psicología Jurídica, 28(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2018a2

González-Álvarez, J. L., López-Ossorio, J. J., Urruela, C., & Díaz, M. R. (2018). Integral Monitoring System in Cases of Gender Violence - VioGén System. Behavior & Law Journal, 4(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.47442/blj.v4.i1.56

González-Álvarez, J. L., Viñas-Racionero, R., Santos-Hermoso, J., Carbonell-Vayá, E., Bermúdez-Sánchez, M. P., Pineda-Sánchez, D., Borrás-Sansaloni, C., Chiclana-de la Fuente, S., Sotoca-Plaza, A., López-Ossorio, J. J., & Garrido-Antón, M. J. (2023). No More Women Killed in Spain! A Collaborative Femicide Prevention Effort of a Police-Led Team of Ministry of Interior and Academia. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 17, paad010. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paad010

González-Prieto, A., Brú, A., Nuño, J. C., & González-Álvarez, J. L. (2023). Hybrid machine learning methods for risk assessment in gender-based crime. Knowledge-Based Systems, 260, 110130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.110130

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000097254001

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jaffe, P. G., Dawson, M., & Campbell, M. (2013). Developing a National Collaborative Approach to Prevent Domestic Homicides: Domestic Homicide Review Committees1. Canadian Journal of Criminology & Criminal Justice, 55(1), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2011.E.53

Johnson, M. P. (2008). A Typology of Domestic Violence: Intimate Terrorism, Violent Resistance, and Situational Couple Violence. Northeastern University Press.

Kafonek, K., Gray, A. C., & Parker, K. F. (2021). Understanding Escalation Through Intimate Partner Homicide Narratives. Violence against Women, 28(15–16), 3635–3656. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012211068057

Koppa, V., & Messing, J. T. (2021). Can Justice System Interventions Prevent Intimate Partner Homicide? An Analysis of Rates of Help Seeking Prior to Fatality. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17/18), 8792–8816. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519851179

López-Ossorio, J. J., González-Álvarez, J. L., & Andrés-Pueyo, A. (2016). Eficacia predictiva de la valoración policial del riesgo de la violencia de género [Predictive effectiveness of the Police Risk Assessment in intimate partner violence]. Psychosocial Intervention, 25(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2015.10.002

López-Ossorio, J. J., González-Álvarez, J. L., Loinaz, I., Martínez-Martínez, A., & Pineda, D. (2021). Intimate partner homicide risk assessment by police in Spain: The dual protocol VPR50-H. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a16

Matias, A., Gonçalves, M., Soeiro, C., & Matos, M. (2020). Intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis of risk factors. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 50, 101358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101358

Messing, J. T., & Campbell, J. C. (2016). Informing Collaborative Interventions: Intimate Partner Violence Risk Assessment for Front Line Police Officers. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 10(4), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paw013

Messing, J. T., AbiNader, M., Bent-Goodley, T., & Campbell, J. (2022). Preventing Intimate Partner Homicide: The Long Road Ahead. Homicide Studies, 26(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/10887679211048492

Myhill, A., & Hohl, K. (2019). The “golden thread”: Coercive control and risk assessment for domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(21–22), 4477–4497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516675464

Nevala, S. (2017). Coercive control and its impact on intimate partner violence through the lens of an EU-wide survey on violence against women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(12), 1792–1820. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517698950

Nicolaidis, C., Curry, M. A., Ulrich, Y., Sharps, P., McFarlane, J., Campbell, D., Gary, F., Laughon, K., Glass, N., & Campbell, J. (2003). Could we have known? A qualitative analysis of data from women who survived an attempted homicide by an intimate partner. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(10), 788–794. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21202.x

Observatorio Estatal de Violencia sobre la Mujer. (2021). XII Informe Anual del Observatorio Estatal de Violencia sobre la Mujer 2018. Ministerio de Igualdad. Centro de Publicaciones (048–20–007–3). https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/observatorio/informesAnuales/docs/XII_Informe_Obsevatorio.pdf

Pomerantz, J. B., Cohen, S. J., Doychak, K., & Raghavan, C. (2021). Linguistic Indicators of Coercive Control: Evidenced in Sex Trafficking Narratives. Violence and Gender, 8(4), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2020.0105

Raghavan, C., Beck, C. J., Menke, J. M., & Loveland, J. E. (2019). Coercive controlling behaviors in intimate partner violence in male same-sex relationships: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 31(3), 370–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2019.1616643

Sabri, B., Campbell, J. C., & Messing, J. T. (2021). Intimate Partner Homicides in the United States, 2003–2013: A Comparison of Immigrants and Nonimmigrant Victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9/10), 4735–4757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518792249

Sciolino, E. (2004). Letter from Europe; Spain Mobilizes Against the Scourge of Machismo. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/14/world/letter-from-europe-spain-mobilizes-against-the-scourge-of-machismo.html

Sheehan, B. E., Murphy, S. B., Moynihan, M. M., Dudley-Fennessey, E., & Stapleton, J. G. (2015). Intimate partner homicide: New insights for understanding lethality and risks. Violence against Women, 21(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214564687

Soria-Verde, M. Á., Pufulete, E. M., & Álvarez-Llaberia, F. X. (2019). Homicidios en la Pareja: Explorando las Diferencias entre Agresores Inmigrantes y Españoles. Anuario De Psicologia Juridica, 29(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2018a14

Stamatel, J. P. (2014). Explaining variations in female homicide victimization rates across Europe. European Journal of Criminology, 11(5), 578–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370814537941

Stark, E. (2007). Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. Oxford University Press.

Taylor, R., & Jasinski, J. L. (2011). Femicide and the Feminist Perspective. Homicide Studies, 15(4), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767911424541

The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). (2019, November 18). Gender-based violence: A guide to risk assessment and risk management of intimate partner violence against women for police. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://eige.europa.eu/publications/guide-risk-assessment-and-risk-management-intimate-partner-violence-against-women-police

Williamson, E. (2010). Living in the world of the domestic violence perpetrator: Negotiating the unreality of coercive control. Violence Against Women, 16(12), 1412–1423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210389162

Wilson, M., Johnson, H., & Daly, M. (1995). Lethal and nonlethal violence against wives. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 37(3), 331–361. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjcrim.37.3.331

Woods, S. J. (2005). Intimate Partner Violence and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Women: What We Know and Need to Know. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(4), 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504267882

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Spanish Secretary of State for Security, Ministry of Interior.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Viñas-Racionero, R., Raghavan, C., Soria-Verde, M.Á. et al. Enhancing the Assessment of Coercive Control in Spanish Femicide Cases: A Nationally Representative Qualitative Analysis. J Fam Viol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00628-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00628-1