Abstract

Purpose

Intimate partner violence (IPV) involves any form of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse including controlling behaviors by an intimate partner. Front line service workers such as social workers, nurses, lawyers, and physicians are often the first professionals to come into contact with individuals experiencing IPV but are often inadequately prepared to respond appropriately as IPV education is highly variable. Experiential learning (EL), also known as learning by doing, has gained much attention from educators; however, the extent and type of EL strategies used to teach IPV competencies has not yet been explored. Our aim was to extract what is known from the literature about the use of EL strategies to teach IPV competencies to front line service providers.

Methods

We conducted a search from May 2021 through November 2021. Reviewers independently screened citations in duplicate using pre-determined eligibility criteria. Data collected included study demographics (publication year, country, etc.), study participants, and information about the IPV EL.

Results

Of 5216 identified studies, 61 were included. Medicine and nursing represented the majority of learners in the included literature. Graduate students were the targeted learners in 48% of articles. Low fidelity EL was used most frequently in 48% of the articles; and role play was the EL mode most frequently utilized (39%) overall.

Conclusions

This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of the limited literature on how EL is used to teach IPV competencies and identifies significant gaps related to the lack of intersectional analysis within educational interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Despite the recognition that optimal learning requires active engagement with new material, many institutions of higher education still focus on traditional teaching methods, such as didactic lectures, even though these methods have been associated with low student engagement and reduced critical thinking among students (Hill, 2017). Learning is a process requiring not only the consumption of knowledge but also an invitation for meaningful learning to occur in the form of building knowledge, skills, and behaviors expected by their chosen disciplines. Such professional expectations of skill level are often referred to as competencies (Drisko, 2014) and relate to a number of areas of client work.

For helping professionals such as social workers, nurses, lawyers, and physicians, IPV is an area that may be regularly encountered and requires specific knowledge and skills in order to respond appropriately. IPV involves any form of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as well as controlling behaviors by an intimate partner (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012). IPV can affect physical and mental health through injury, prolonged stress responses, and the development of chronic illness as the influence of IPV can be cumulative and persist long after the violence has ended (Dutton et al., 2015). With inadequate education, professionals who often come into contact with victims of IPV can struggle to assess, recognize, and make proper recommendations when dealing with IPV (Raja et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2018; Taft et al., 2004).

While much progress has been made in IPV education, the teaching of the topic is often highly variable and inconsistent between professions, institutions, and individual practices (Academy on Violence and Abuse [AVA], 2011; Skrundevskiy et al., n.d.) and can be traced at both the student level and continuing education level (Buranosky et al., 2012; Manuel et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2007). Experiential learning (EL), also known as learning by doing, has gained much attention from educators within higher educational institutions; however, we do not know the extent and type of EL strategies used to teach IPV competencies to frontline workers, like social workers, nurses, and lawyers. With IPV being a major global public health and social justice concern, an investigation into this topic is a priority because focused IPV knowledge and training is a necessity for professionals to provide specialized care and services to the millions of individuals worldwide experiencing IPV (Cotter, 2021).

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to extract from the literature what is known about the use of EL strategies to teach IPV competencies to front line helping professionals. In this review, we explored the type of learners, IPV types, IPV competencies, types of EL activities, the use of debriefing when EL was used, outcomes of the EL activities, and whether intersectionality was considered in the design of EL activities.

Methods

This review was designed and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guideline. We adhered to the PRISMA-ScR Extension for Scoping Reviews to report findings (Supplemental Digital Appendix 1).

Data Sources and Searches

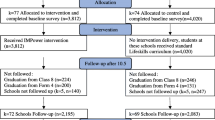

A search strategy was developed that combined subject headings and synonyms for two concepts: 1) EL; and 2) IPV. We were interested in literature from all professions and educational programs, so searches were conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, Hein Online, Academic Search Complete, Canadian Business and Current Affairs, Gale Academic Onefile, Criminal Justice Abstracts, ABI Business Premium Collection, Business Source Complete, SSRN, PsycInfo, PsycArticles, ERIC, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, Family Studies Abstracts, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX, and Sociological Abstracts, from database inception to November 2021 without any limits on languages or dates. The complete MEDLINE search strategy can be found in the Supplement (Supplemental Digital Appendix 2). Identified studies were exported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation) and duplicates were removed (Fig. 1).

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).- excluded by automation tools. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they were primary research that described EL opportunities on the topic of IPV. For the purpose of this review, EL was defined as “learning-by-doing that bridges knowledge and experience through critical reflection” (University of Calgary, 2020, p. 5). We included English-language quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies published in any year. Studies were excluded if the focus of EL was not IPV, or if the instructional strategy employed was not considered EL. All systematic, scoping or literature reviews were excluded, as were any editorials or commentaries.

Study Selection

All titles and abstracts were reviewed independently and in duplicate by authors (KW, AA, AW, and TJ). Studies progressed to full-text screening upon reviewer agreement, or after discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (KW). The same process was repeated for full-text screening.

Data Extraction

We extracted data for each included study using a data collection form developed by the study team. We extracted information on study characteristics (e.g., year of publication, country, study design), population demographics (e.g., profession, learner stage), and experiential learning details (e.g., setting, timeframe, type of experiential learning, IPV competencies, debriefing, outcomes, intersectionality).

Data were categorized according to the topics of interest. Learners were categorized by professional affiliation (medicine, nursing, law, etc.) and by stage of training (undergraduate student, graduate student, resident, graduated professional). The IPV that was the focus of the EL was categorized by characteristics of the individual experiencing the violence, including IPV between partners, involving pregnant women, involving families with children, and involving older adults. IPV competencies refer to what educational objectives learners should acquire after participating in IPV-focused education (AVA, 2011). We categorized the IPV competencies found in the articles of this literature review as outlined by the AVA. The AVA IPV competencies are organized into three categories based on who the competencies are intended for: health systems, educational institutions, and individual learners (2011). Individual learner competencies are further broken down into three subcategories: knowledge, skills, and attitudes (AVA, 2011). Data were also categorized based on the type of EL employed, the number of EL modes used, and the fidelity, or realism, of the activity. Outcomes were reviewed and categorized with reference to learning objectives in terms of beneficial change, no change, and mixed results. No incidences of negative change outcomes were noted. Outcomes were then further categorized into knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA) to reflect the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL) Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice: Outcomes and Objectives (Miller et al., 2021). Articles were also assessed for transfer of learning and the described retention or sustainability of outcomes. Additionally, the data were categorized based on the presence or absence of discussion on intersectionality and debriefing. Debriefing was further broken down into the debriefing framework utilized and when the debriefing activities occurred. For all definitions, see Data Dictionary (Supplementary Table 1).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Extracted data were descriptively analyzed to reveal the current state of empirical knowledge about EL for IPV. Descriptive statistics were calculated using Stata IC 15 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

From 5216 initial citations, 4282 unique abstracts were screened after duplicates removed, 196 full-text articles were reviewed, and 61 studies were included in the final analysis.

Over half of the 61 included studies were published during or after the year 2010 (n = 32, 52%). The included studies were primarily conducted in the United States (n = 46, 75%); four (7%) were conducted in Canada, three (5%) were conducted in Australia, and the remaining studies were conducted elsewhere. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of included studies and the experiential learning opportunities they describe.

Learners

The sample size of learners was reported in 54 articles (88%), resulting in a median of 48 [IQR: 28–99]. Medicine and nursing represented the majority of learners in the included literature, with 46 of the 61 articles (75%) being explicitly dedicated to medicine (n = 26, 43%) or nursing (n = 15, 25%), or a combination involving both (n = 5, 8%). Two studies did not clearly state the type of learner involved. Undergraduate students were the targeted learners in 15 (25%) articles, with 11 (73%) being focused solely on undergraduates, and the remainder being a combination of undergraduates and graduates or practicing professions.

Most undergraduate learners were nursing students. Others included social work (n = 1, 7%), midwifery (n = 1, 7%), architecture and landscaping (n = 1, 7%), and physical therapy students (n = 1, 7%). Graduate students were the targeted learners in 29 (48%) articles, with 27 (93%) being solely dedicated to graduate students, and two being mixed with undergraduate students. Most graduate learners were medical residents. Other graduate learners included social work (n = 2, 7%), law (n = 3, 10%), pharmacy (n = 1, 3%), public health (n = 1, 3%), therapy (n = 1, 3%), nursing (n = 1, 3%), and dental students (n = 1, 3%).

Practicing professionals were the targeted learners in 21 (34%) articles, with 19 (91%) being solely focused on practicing professionals, and two articles mixed with practicing professionals and undergraduate students. Physicians and nurses were among the majority of learners in these articles; other practicing professionals included physiotherapists (n = 1, 5%), physician assistants (n = 2, 10%), social workers (n = 3, 14%), police (n = 1, 5%), and midwives (n = 2, 10%). Two articles were not explicitly clear on the type of learners that participated (Mason et al., 2017; Ritchie et al., 2013).

Types of IPV

Less than half of the included articles (n = 22, 36%) reported the type of IPV that was addressed by the EL opportunity. Of these, seven (32%) articles focused on addressing violence between partners, six articles (27%) focused on IPV during pregnancy, and four articles (18%) focused on violence between partners within families with children. Five articles (23%) described multiple types of IPV, with four (18%) of these addressing violence between partners and violence involving families with children and one article (5%) addressing violence involving pregnancy as well as violence between older adults.

IPV Competencies

Most of the articles (n = 41, 67%) reported specific IPV competencies as a part of the learning goals in the EL activities. The majority (n = 37, 61%) reported competencies targeted at independent learners that could be categorized into knowledge, skills, attitudes, or any combination. Knowledge and attitudes combined were the most common competencies (n = 14, 38%), followed by knowledge, skills, and attitudes combined (n = 8, 22%) and knowledge and skills combined (n = 8, 22%), followed by skills alone (n = 3, 8%), and attitudes alone (n = 3, 8%); skills combined with attitudes (n = 1, 3%) was the least common competency. Knowledge alone was not a noted competency. Of the 41 articles that reported specific IPV competencies, only 16 reported some sort of IPV competency framework. These frameworks included reported goals that were separate and overarching from the stated learning objectives and competencies, as well as cited references to other pre-existing IPV frameworks. Examples of competencies within these frameworks include violence prevention strategies, safety planning, and legal/forensic responsibilities (Short et al., 2006). Only five articles referenced using or drawing from pre-existing frameworks, these included: The Abuse Assessment Screen (Bermele et al., 2018), 2014 National Patient Safety Goals (Bryant & Benson, 2015), It’s Time to Ask Curriculum (Johnson et al., 2009), New South Wales Health Policy (Boursnell & Prosser, 2010), and the University of Tennessee Domestic Violence Learning Module (Helton & Evans, 2001).

Experiential Learning

Role play was the EL mode most frequently described, with 24 (39%) instances noted. EL involving standardized patient (SP) experiences (n = 22, 36%), discussions (n = 18, 30%), and video (n = 18, 30%) were also described in several articles. Other modes of EL that were used included case studies (n = 10, 16%), survivor stories (n = 8, 13%), online modules (n = 5, 8%), practicums (n = 5, 8%), simulations using manikins (n = 4, 7%), workshops (n = 4, 7%), presentations/performances (n = 3, 5%), attending court (n = 2, 3%), and training (n = 2, 3%). Additionally, scenario development, rehearsals, interclerkship, peer training, and experiential assignments were each noted with a single instance (n = 1, 2%).

Examining the total number of EL modes within each study revealed that the majority (n = 41, 67%) of studies used one (n = 21, 34%) or two (n = 20, 33%) modes, while only six (10%) articles described using four or more modes of EL, with a maximum of five noted in three (5%) of the articles.

Fidelity describes the degree of realism to which the experience replicates the real events or workplace, and may include physical, psychological, and environmental elements, among others (Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 2020). Low fidelity experiences include examples such as case studies, role play, or task trainers, while high fidelity experiences offer high degrees of realism, interactivity, or replication of real events, including SP simulations, high fidelity manikin simulations, and practicum experience (Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 2020). Low fidelity EL was used most frequently in 29 (48%) of the articles, while high fidelity was used in 18 (30%) of the articles. Additionally, we noted 13 (21%) instances of mixed fidelity with articles describing a combination of both low and high fidelity EL modes. In total, over half of the articles (n = 31, 51%) described some element of high fidelity. Of these, SP experiences (n = 22, 71%) were the most frequently noted high fidelity EL. Most of the articles (n = 50, 82%) reported on the length of time for EL, resulting in a median of four hours [IQR: 2–12 h].

Debriefing

One third (n = 21, 34%) of the included articles described debriefing after the experiential learning opportunity. Of those, 17 (81%) did not specify the method of debriefing used. Two of the articles utilized plus-delta debriefing, asking participants to reflect on their experience and assess what their groups did or did not do well in the scenarios (Johnson & Montgomery, 2017; Stevens et al., 2020). One study utilized the Describing, Examining and Articulating Learning method (Clayton & Ash, 2009) of debriefing in which participants were encouraged first to describe the overall learning experience, second to examine their own feelings and reactions, and finally, to articulate the major themes and key takeaways that they understood (McKinney et al., 2016). Another study utilized the Gather, Analyze, and Summarize debriefing tool (Phrampus & O’Donnell, 2013), prompting the learners to articulate what went well, which areas of the learning module needed improvement, and to reflect on evidence-based best practice approaches (Jiménez-Rodríguez et al., 2020).

Most of the studies that described debriefing (n = 17, 81%), debriefed the learners immediately after the intervention. Two studies debriefed the learners during and immediately after the EL activity, and one study debriefed the learners during the intervention. One study did not specify the timing of debriefing.

Outcomes

Most of the included articles (n = 58, 95%) reported a benefit in learning outcomes; two articles reported no change, and one reported mixed results. Of the included articles, 54 (89%) contained sufficient descriptions of outcomes to then be categorized into KSA. Knowledge outcomes were noted in 44 (81%) of these articles, attitude outcomes were noted in 37 articles (69%), and skills outcomes were noted in 30 (56%) articles. Concurrent knowledge and attitudes outcome measurements were the most common, n = 19 (35%), while concurrent knowledge and skills (n = 13, 24%), and KSA (n = 12, 22%) were also noted quite frequently. Concurrent skills and attitudes outcome measurements were the least common (n = 1, 2%). Furthermore, only nine (17%) articles described singular competency outcomes in isolation, skills (n = 4, 7%) or attitudes (n = 5, 9%) and interestingly there were no (n = 0) instances of knowledge outcomes being measured independently despite being the most frequently observed (n = 44, 81%).

Transfer of learning was discussed in 12 (20%) of the included articles. Most (n = 11, 92%) described positive retention of partial to all measured outcomes at follow-up assessments ranging from three to 12 months.

Intersectionality

Seven (11%) of the 61 articles made mention of IPV being connected to some identity category outside of gender. Two (n = 2, 3%) of the seven articles discussed the intersection of race and gender in association with IPV (Salmon et al., 2006; Richardson & Speed, 2019), while four (n = 4, 6%) of the seven made mention of disability and gender associated with IPV (Alpert et al., 2002; Mason et al., 2017; Short et al., 1997; Thompson et al., 1998), and only one (n = 1, 1%) referenced race, disability, and gender (Blaney, 2010). Of the seven articles that mentioned intersecting identities, only one (n = 1, 1%) article incorporated intersectionality into their learning activity, focusing on IPV and addiction specifically (Alpert et al., 2002). In contrast with other studies that merely recognized intersectionality when creating their learning activities, Alpert et al. (2002) incorporated a discussion of the intersection of domestic violence and other public health issues such as homelessness, HIV/AIDS, immigration, substance abuse, teen pregnancy, and child welfare throughout the learning activity.

Discussion

IPV education includes opportunities for EL. In fact, this scoping review revealed that EL strategies are effective in teaching the KSA concerning IPV competencies. In this discussion, we want to contribute to the conversation around the context for IPV education, particularly within competency-based education and instructional design and the emphasis on EL in higher education. Social workers, nurses, and lawyers are often involved in witnessing and navigating social problems like IPV and we would be remiss if we do not address intersectionality as a critical aspect of each discipline and how this concept shapes the way we engage in social justice work (Collins & Bilge, 2020). Although the majority of learners found in the scoping review were from the disciplines of medicine, nursing and social work, there is a growing movement to address IPV within the legal community. Legal education has traditionally been taught using orthodox, hegemonic pedagogies and legal educators often lacked the infrastructure to enable the development of new curricula (Phillips et al., 2016). However, as EL has become more popular within legal education, law schools have recognized opportunities to implement EL in the area of family law, thus teaching students about IPV (Phillips et al., 2016).

IPV Competencies and Competency Based Education

Competency based education is prevalent in health related disciplines and is defined as preparing learners for practice based on outcome abilities and competencies derived from societal and patient/client needs, where the focus is taken off of hours of training and instead emphasizes learner centeredness, flexibility, and greater accountability (Frank et al., 2010). In medicine, social work, and nursing, competence pertains to the use of one’s cognitive, psychomotor, and affective skills, also known as KSA (Epstein & Hundert, 2002; Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, (n.d.); Fukada, 2018) in their practice. The language of KSA in relation to education is commonly associated with Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of educational objectives which comprises of three domains: cognitive/knowledge (acquiring and utilizing knowledge), psychomotor/skills (performing skills and tasks), and affective/attitude (relating to awareness and value) (Nascimento et al., 2021). Within the IPV literature, goals related to KSA competencies were prevalent even over 20 years ago (Brandt, 1997). Furthermore, these same three domains to guide learning competencies can be found in IPV education internationally and is not limited to North America. For example, Manuel et al. (2019) explored the mastery of IPV competencies among medical students in Mozambique. A majority of the literature reviewed utilized some combination of KSA competencies in their evaluation methods. Although IPV competencies can be cited as early as the 1990’s, a key finding from our work highlighted the inconsistency of the use and description of specific IPV competencies to guide IPV education among front line service workers. Where IPV competencies were used, these included violence prevention strategies, safety planning, and legal/forensic responsibilities (Short et al., 2006).

Prior to the implementation of the Federation of Law Societies of Canada’s 2009 Task Force on the Canadian Common Law Degree Final Report (the Task Force), competency based education in the legal profession was less explicitly discussed. Legal education has always encompassed knowledge as a core competency, specifically the “black letter legal rules” (Rochette & Pue, 2001, p. 188). However, the traditional teaching methods of legal institutions, while effective in conveying legal knowledge, have historically failed to effectively teach skills to law students (Rochette, 2011). The traditional lecture-style method of teaching, and final examination method of evaluation, fail to adequately teach students skills such as critical thinking, analysis, and synthesis (Rochette, 2011). In 2009 the Task Force recommended that law students be required to be competent in skills, ethical values, and legal knowledge. Skills include problem solving, legal research, and oral and written legal communication competencies, while ethical values include a duty to communicate with civility, address ethical dilemmas, and understand ethics and professionalism. Teaching ethical values, or values more broadly, has been incorporated historically in legal education implicitly (Rochette, 2011). Law is an inherently value laden discipline, with moralistic considerations infused within every legal judgment (Rochette, 2011). With the exception of the requirement of a course in ethics, many values such as the social context of law and cultural competence are often taught implicitly or through elective courses (Rochette, 2011). As legal education and practice have diversified, there has been an increasing call to incorporate different teaching and learning methods into legal education, including self-reflective practice, cultural competency, and outsider pedagogies, so as to alter the often-exclusionary nature of the legal profession (Bakht et al., 2007; Voyvodic, 2005).

In 1994, experts on family violence prevention and management from different disciplines convened during a conference on Family Violence and Health Professions Education where they called for the creation of specific curricular goals and objectives to frame the education and training of health professionals regarding IPV (Brandt, 1997). Acknowledging the important role institutions play in supporting curricula, the AVA (2011) not only named individual competencies expected of health professionals but also highlighted the institutional (both educational and health system) competencies required to support the training of those at the frontline of this public health concern.

Training programs ought to strive to meet all three domains of learning in relation to IPV education as it is not sufficient to focus education initiatives solely on knowledge gain. Educators could also consider using Miller’s (1990) pyramid where learning is scaffolded into four elements—knows (knowledge), knows how (competence), shows how (performance), and does (action). Competencies, then, cannot simply rest on the acquisition of information but culminate in one’s ability to act on what they have come to know which aligns well with Brandt’s (1997) emphasis on the use of EL within IPV curricula such as the use of “videotape presentations, role plays, standardized patients” (p. 53) particularly when direct community experience is not feasible as a way to create meaningful and authentic learning experiences.

Experiential Learning

While traditional lecture teaching methods are widely used in higher education, research has identified concerns with this method regarding student engagement and the development of a deeper understanding of key concepts (Hill, 2017). Furthermore, teaching and learning recommendations suggest that student engagement through active learning is essential in the adult learning process and the development of skills (Fry et al., 2015; Hill, 2017). EL enables students to learn through experiences, or ‘doing’, and through this encourages the learner to act as an active participant in the learning experience and encourages students to apply knowledge and skills in a practical setting (Hills, 2017; Morris, 2019).

In the case of simulation-based learning experiences as an example of EL, the level of realism or trueness to which they replicate or resemble the ‘real world’, known as fidelity (Gu et al., 2017), has been a topic for debate. While both low and high fidelity simulations were effective in improving procedural skill performances (Lefor et al., 2020), studies have shown that this might not always be the case, particularly when examining non-technical skill acquisition (Gu et al., 2017; Lefor et al., 2020). A 2017 review on the effects of fidelity on non-technical skill acquisition revealed no significant difference between low and high fidelity simulators, suggesting that low fidelity EL is as effective as high fidelity for teaching non-technical skills (Gu et al., 2017). Our review of the included articles revealed a range of fidelity utilized in IPV EL education, with over half of the articles describing some element of high fidelity experience. Despite this range of fidelity, overwhelmingly the results indicated positive outcomes associated with EL in IPV education with 95% of the articles reporting beneficial changes to measured outcomes. These findings suggest that either low, high, or mixed fidelity could be effectively utilized and that fidelity should be selected by the IPV educators to best fit the learning outcomes and IPV competencies. The three articles that reported no change (n = 2) or mixed results (n = 1) included one low fidelity, one high fidelity, and one mixed high-low fidelity suggesting no connection between fidelity and negative outcomes (Brienza et al., 2005; Donnelly et al., 2019; Ritchie et al., 2013).

Role-play was the most commonly described EL mode utilized at 39% of included studies. Role-play is a cost-effective and generally easy to set up EL mode that enables students to actively engage in a scenario or profession-specific setting to practice and develop non-technical skills, such as communication, decision-making, or leadership skills, and improve learners’ abilities to face similar situations in their future professional practice (Gelis et al., 2020). However, due to the inherent nature of role-play, with the other roles often played by other learners or otherwise untrained actors, educators have less control over the scenario progression and content (Gelis et al., 2020). SP simulations offer a solution to this concern, providing a more structured and controlled learning environment and thus also reducing inter-group variability (Gelis et al., 2020). However, SP experiential learning encounters are often linked with significantly increased costs associated with securing appropriately trained actors. A 2020 systematic review suggested that the cost of using SPs could be as high as five times greater than the cost associated with peer-role play (Gelis et al., 2020). Although, of the included articles that only used one mode of EL (n = 21, 34%), SP experiences accounted for 57% (n = 12) of these and furthermore accounted for two-thirds (n = 12, 67%) of all the exclusively high-fidelity experiences (n = 18, 30%). The majority (67%) of included studies utilized one or two modes of EL with role play and SP experiences noted as familiar combinations. Of these, three articles described utilizing role-play early in the educational experiences with the SP encounter falling into the later stages. All three articles reported positive outcomes; however, Glowa et al. (2002) reported no significant improvements in outcomes after the role-play alone but instead only after learners participated in the SP exercise. These findings suggest that IPV educators could utilize multi-mode high-low fidelity combined EL of role-play and SP simulations as an effective and cost-efficient method of providing the learner with multiple exposures to IPV EL. However, further research is required to substantiate this.

Debriefing

EL through simulation is a novel and effective means of education, especially in interprofessional education (Boet et al., 2013). Debriefing is the process in which learners reflect on their experience and performance to consider what they have done well and where they could improve (Boet et al., 2013). Debriefing is critical to the success of EL (Boet et al., 2013). The fact that the majority of the articles included in the scoping review (66%) did not discuss debriefing demonstrates a potential knowledge-practice gap. However, it should be noted that mere failure to discuss debriefing in an article does not necessarily mean debriefing did not occur. Despite that, the importance of debriefing to integrate learning in simulation should be underscored (Boet et al., 2013).

Intersectionality

IPV is the most common form of violence reported by women, and it affects women disproportionately as compared to men (Conroy, 2021). It also affects women of all intersecting identities (Cotter, 2021; Mason et al., 2017), Indigenous women, women with disabilities, young women, and sexual minority women being at heightened risk (Heidinger, 2021; Jaffray, 2021; Savage, 2021). The fact that only 11% of the articles included in the scoping review included some element of intersectionality demonstrates that the vast majority of initiatives teaching IPV fail to account for the reality of survivors’ experiences, thus failing to adequately prepare practitioners for service-user realities.

Our common conception of the “typical” victim of IPV often erases social position from what becomes the essential victim, resulting in the construction of IPV victims as white, female, heterosexual, and middle-class (Coker, 2016; Lockhart & Danis, 2010; MacDowell & Cammett, 2016; McQueeney, 2016). Such construction of the typical victim results in policies, interventions, and supports that fail to meet the needs of racialized women, Indigenous women, two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (2SLGBTQ +) individuals, and immigrant women (Coker, 2016; Duhaney, 2021; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019). The exclusion of intersectional analysis in societal responses to IPV has, for some groups and communities, resulted in increased violence. Consider that the primary response to IPV is the criminal justice system; the same system that disproportionately targets people of color and 2SLGBTQ + individuals (McQueeney, 2016). For many, the criminal justice system increases the violence they experience; it does not prevent or stop it (McQueeney, 2016). An intersectional analysis of the lived experiences of victims of IPV must go further to consider the intersections of the policies and institutions which serve to further marginalize victims, such as immigration laws, charging and prosecution policies, employment policies, housing policies, and policies of shelters and victim services (McQueeney, 2016; Lockhart & Danis, 2010; Duhaney, 2021). All of this is crucial to how IPV is taught. The one study that included a more fulsome intersectional analysis, including race, disability, and gender, resulted in positive outcomes for learners, with learners reporting an increased understanding of IPV and ability to respond to IPV (Blaney, 2010). This highlights the need for including a robust intersectional discussion within experiential learning.

Research in the medical field has shown that individual outcomes depend on the impact of intersecting oppressions on each client (Monrouxe, 2015). Such studies have called for the inclusion of an intersectional framework in cultural competence education (Monrouxe, 2015). Practitioners must be adequately trained with skills and techniques which account for the diversity of experiences of victims of IPV (Lockhart & Danis, 2010). Identity is not static, rather everyone occupies multiple intersecting identities over time and in different contexts. Education should not be devoid of the reality in which learners and clients exist (Nichols & Stahl, 2019). Failure to account for the diversity of intersectional identities in IPV education results in a failure to adequately prepare learners for the reality in which they will be practicing. This may in turn do their patients and clients a disservice, or worse, it may cause further harm. Incorporating intersectionality into educational interventions targeting IPV is necessary to account for the breadth of survivors’ lived experiences, and it may also assist students in thinking about larger scale systemic change (McQueeney, 2016). However, the relative infrequency in which intersectionality is considered in the literature demonstrates a significant gap. Our scoping review demonstrates how inadequately learners are being prepared for dealing with IPV and demonstrates that many learners may still be directed to consider the average IPV victim as the essential victim, devoid of any social context.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review has several strengths. This review was conducted by a multi-disciplinary team involving those with expertise from social work, nursing, and law backgrounds. A systematic approach was utilized with multiple reviewers, and the search strategy and inclusion terms were comprehensive and inclusive to capture a broad amount of terminology related to IPV and EL. Limitations of this review include only using studies in English and articles with full text availability or abstracts with sufficient detail, potentially excluding possibly relevant literature. Another limitation of this review is the representativeness of the results, as the majority of the included articles were conducted in the United States (n = 46, 75%), potentially leading to conclusions that are weighted to an American education system. Additionally, this scoping review only surveys experiential learning initiatives that have been published and there is undoubtedly teaching and learning that occurs relating to IPV that is not published. Further initiatives to assist educators in documenting and evaluating learning outcomes is needed.

Conclusion

Front line service providers in the helping professions often feel inadequately prepared to help victims of IPV, highlighting the need for training in this area. EL can be an effective tool in teaching professionals such as social workers, lawyers, nurses, and doctors how to respond to IPV. This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of evaluations of EL used to teach IPV competencies. While higher education programs are incorporating IPV into the curriculum, it is inconsistent and dependent on the profession and the institution. Additionally, there is a significant gap in incorporating an intersectional analysis into educational interventions, and such lack of intersectionality may serve to perpetuate or even increase harm for victims of IPV. Regardless of the design of the educational intervention, there exists a need to further educate the helping professions on the reality of IPV and how best to provide care for victims of IPV.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

Academy on Violence & Abuse. (2011). Competencies needed by health professionals for addressing exposure to violence and abuse in patient care. https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/CoreCompetenciesRevApril2011.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2021.

Alpert, E. J., Shannon, D., Velonis, A., Georges, M., & Rich, R. A. (2002). Family violence and public health education: A call for action. Violence against Women, 8(6), 746–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778010222183260

*Auten, J. D., Ross, E. M., French, M. A., Li, I. Z., Robinson, L., Brown, N., King, K. J., & Tanen, D. A. (2015). Low-fidelity hybrid sexual assault simulation training’s effect on the comfort and competency of resident physicians. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 48(3), 344–350.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.09.032.

*Bermele, C., Andresen, P. A., & Urbanski, S. (2018). Educating nurses to screen and intervene for intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Nursing for Women’s Health, 22(1), 79–86.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2017.12.006.

*Blaney, E. (2010). Police officers’ views of specialized intimate partner violence training. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 33(2), 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511011044939.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Longmans, Green.

Blumling, A., Kameg, K., Cline, T., Szpak, J., & Koller, C. (2018). Evaluation of a standardized patient simulation on undergraduate nursing students’ knowledge and confidence pertaining to intimate partner violence. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 14(3), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/jfn.0000000000000212

Boet, Bould, M. D., Sharma, B., Revees, S., Naik, V.N., Triby, E., & Grantcharov, T. (2013). Within-team debriefing versus instructor-led debriefing for simulation-based education: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 258(1), 53–58.https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829659e4.

*Boursnell, M., & Prosser, S. (2010). Increasing identification of domestic violence in emergency departments: A collaborative contribution to increasing the quality of practice of emergency nurses. Contemporary Nurse, 35(1), 35–46.https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2010.35.1.035.

Brandt, E. N. (1997). Curricular principles for health professions education about family violence. Academic Medicine, 72(1), 51–58. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=ovftc&NEWS=N&AN=00001888-199701000-00034.

*Brienza, R. S., Whitman, L., Ladouceur, L., & Green, M. L. (2005). Evaluation of a women’s safe shelter experience to teach internal medicine residents about intimate partner violence. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(6), 536–540.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0100.x.

*Bryant, S. G., & Benson, K. H. (2015). Using simulation to introduce nursing students to caring for victims of elder abuse and intimate partner violence. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36(6), 408–409.https://doi.org/10.5480/15-1609.

*Buranosky, R., Hess, R., McNeil, M. A., Aiken, A. M., & Chang, J. C. (2012). Once is not enough: Effective strategies for medical student education on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 18(10), 1192–1212.https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212465154.

*Cheek, T., Rector, K., & Davis, C. (2007). The clothesline project: An experiential learning project with MSW students.Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 27(1-2), 141–154.https://doi.org/10.1300/j067v27n01_09.

Clayton, P. H., & Ash, S. L. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 41(1–2), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2016.1258623

Coker, D. (2016). Domestic violence and social justice: A structural intersectional framework for teaching about domestic violence. Violence against Women, 22(12), 1426–1437. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215625851

*Colarossi, L., & Forgey, M. (2006). Evaluation study of an interdisciplinary social work and law curriculum for domestic violence. Journal of Social Work Education, 42(2), 307–323.https://doi.org/10.5175/jswe.2006.200400497.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Conroy, S. (2021). Spousal violence in Canada, 2019. Juristat, 4–39.

Cotter, A. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Experiences of visible minority women in Canada, 2018. Juristat, 1–16.

*Davila, Y. R. (2006). Increasing nurses’ knowledge and skills for enhanced response to intimate partner violence. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 37(4), 171–177.https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20060701-05.

*Donnelly, S., Dean, S., Razavy, S., & Levett-Jones, T. (2019). Measuring the impact of an interdisciplinary learning project on nursing, architecture and landscape design students’ empathy. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0215795. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215795.

Drisko, J. W. (2014). Competencies and Their Assessment. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(3), 414–426.

Duhaney, P. (2021). Contextualizing the experiences of black women arrested for intimate partner violence in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211056723.

Dutton, M. A., James, L., Langhorne, A., & Kelley, M. (2015). Coordinated public health initiatives to address violence against women and adolescents. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(1), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4884

*Elman, D., Hooks, R., Tabak, D., Regehr, G., & Freeman, R. (2004). The effectiveness of unannounced standardised patients in the clinical setting as a teaching intervention. Medical Education, 38(9), 969–973.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01919.x.

Epstein, R., & Hundert, E. (2002). Defining and Assessing Professional Competence. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(2), 226. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226

*Evans, G. W., Helton, S. M., & Blackburn, L. S. (2001). Students go to court: Experiential learning about domestic violence. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 7(3), 84–88.https://doi.org/10.1067/mpn.2001.116053.

Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. (n.d.). Competency for Professional Practice. https://socialwork.utoronto.ca/competency-for-professional-practice/. Accessed 20 Dec 2021.

*Fasina, A. A. (2010). Implementing a sexual assault training for nurses at JFK memorial center in Monrovia, Liberia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 83(5), 157–158.

*Forgey, M. A., Badger, L., Gilbert, T., & Hansen, J. (2013). Using standardized clients to train social workers in intimate partner violence assessment. Journal of Social Work Education, 49(2), 292–306.https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2013.768482.

Frank, J. R., Mungroo, R., Ahmad, Y., Wang, M., De Rossi, S., & Horsley, T. (2010). Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: A systematic review of published definitions. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 631–637. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.500898

Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., & Marshall, S. (2015). A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: Enhancing academic practice (4th ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Fukada, M. (2018). Nursing competency: Definition, structure and development. Yonago Acta Medica, 61(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.33160/yam.2018.03.001.

Gelis, A., Cervello, S., Rey, R., Llorca, G., Lambert, P., Franck, N., Dupeyron, A., Delpont, M., & Rolland, B. (2020). Peer role-play for training communication skills in medical students. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 15(2), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0000000000000412

Glowa, P. T., Frasier, P. Y., & Newton, W. P. (2002). Increasing physician comfort level in screening and counseling patients for intimate partner violence: Hands-on practice. Patient Education and Counseling, 46(3), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00215-4

Gu, Y., Witter, T., Livingston, P., Rao, P., Varshney, T., Kuca, T., & Dylan Bould, M. (2017). The effect of simulator fidelity on acquiring non-technical skills: A randomized non-inferiority trial. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 64(12), 1182–1193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-017-0973-2

*Haist, S. A., Wilson, J. F., Pursley, H. G., Jessup, M. L., Gibson, J. S., Kwolek, D. G., Stratton, T. D., & Griffith, C. H. (2003). Domestic violence: Increasing knowledge and improving skills with a four-hour workshop using standardized patients. Academic Medicine, 78(Supplement), S24–S26.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200310001-00008.

Harris, J. M., Kutob, R. M., Surprenant, Z. J., Maiuro, R. D., & Delate, T. A. (2002). Can internet-based education improve physician confidence in dealing with domestic violence. Family Medicine, 34(4), 287–292.

*Hayward, K. S., & Weber, L. M. (2003). A community partnership to prepare nursing students to respond to domestic violence. Nursing Forum, 38(3), 5–10.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0029-6473.2003.t01-1-00005.x.

Heidinger, L. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada, 2018. Juristat, 1–21.

*Helton, S. M., & Evans, G. W. (2001). “She looked just like me” a domestic violence learning module. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22(5), 503–516.https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840120752.

*Heron, S. L.,Hassani, D. M., Houry, D., Quest, T., & Ander, D. S. (2010). Standardized patients to teach medical students about intimate partner violence. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 11(5), 500–505.

Hill, B. (2017). Research into experiential learning in nurse education. British Journal of Nursing, 26(16), 932–938. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.16.932.

*Hodgson, J. L., Lamson, A. L., & Feldhousen, E. B. (2007). Use of simulated clients in marriage and family therapy education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(1), 35–50.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00003.x.

*Insetta, E. R., & Christmas, C. (2017). Assessment of a curriculum on intimate partner violence (IPV) for internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32, S120-121.

*Insetta, E. R., & Christmas, C. (2020). A novel intimate partner violence curriculum for internal medicine residents: Development, implementation, and evaluation. AAMC Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10905.

Jaffray, B. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority women in Canada, 2018. Juristat, 1–18.

*Jayatilleke, A. C., Yoshikawa, K., Yasuoka, J., Poudel, K. C., Fernando, N., Jayatilleke, A. U., & Jimba, M. (2015). Training Sri Lankan public health midwives on intimate partner violence: A pre- and post-intervention study. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 331.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1674-9

*Jiménez-Rodríguez, D., Belmonte García, M. T., Santillán García, A., Plaza del Pino, F. J., Ponce-Valencia, A., & Arrogante, O. (2020). Nurse training in gender-based violence using simulated nursing video consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8654.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228654.

*Johnson, N. L., Klingbeil, C., Melzer-Lange, M., Humphreys, C., Scanlon, M. C., & Simpson, P. (2009). Evaluation of an intimate partner violence curriculum in a pediatric hospital. Pediatrics, 123(2), 562–568.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3121.

*Johnson, P., & Montgomery, M. (2017). Improving nursing students’ comfort dealing with intimate partner violence. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 12(4), 286–288.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2017.07.002.

*Jonassen, J. A., Pugnaire, M. P., Mazor, K., Regan, M. B., Jacobson, E. W., Gammon, W., Doepel, D. G., & Cohen, A. J. (1999). The effect of a domestic violence interclerkship on the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of third-year medical students. Academic Medicine, 74(7), 821–828.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199907000-00017.

*Korenstein, D., Thomas, D. C., Foldes, C., Ross, J., Halm, E., & McGinn, T. (2003). An evidence-based domestic violence education program for internal medicine residents. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(4), 262–266.https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1504_09.

*Kripke, E. N., Steele, G., O’Brien, M. K., & Novack, D. H. (1998). Domestic violence training program for residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13(12), 839–841.https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00248.x.

Lefor, A. K., Harada, K., Kawahira, H., & Mitsuishi, M. (2020). The effect of simulator fidelity on procedure skill training: A literature review. International Journal of Medical Education, 11, 97–106. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5ea6.ae73

Lockhart, & Danis, F. S. (2010). Domestic violence: Intersectionality and culturally competent practice. Columbia University Press.

*Marken, P. A., Zimmerman, C., Kennedy, C., Schremmer, R., & Smith, K. V. (2010). Human simulators and standardized patients to teach difficult conversations to interprofessional health care teams. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(7), 120.https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7407120.

*Mason, R., Wolf, M., O’Rinn, S., & Ene, G. (2017). Making connections across silos: Intimate partner violence, mental health, and substance use. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0372-4.

MacDowell, & Cammett, A. (2016). Models of invisibility: Rendering domestic and other gendered violence visible to students through clinical law teaching. Violence Against Women, 22(12), 1438–1450.https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215625853.

Manuel, B., Roelens, K., Tiago, A., Keygnaert, I., & Valcke, M. (2019). Gaps in medical students’ competencies to deal with intimate partner violence in key Mozambican medical schools. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00204

*McCauley, J., Jenckes, M. W., & McNutt, L. (2003). ASSERT: The effectiveness of a continuing medical education video on knowledge and attitudes about interpersonal violence. Academic Medicine, 78(5), 518–524.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200305000-00017.

*McKinney, J., O’Connor, V., & Pruitt, D. (2016).Experiential learning through group work and theater. Social Work with Groups, 41(1-2), 49–59.https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2016.1258623.

McQueeney, K. (2016). Teaching domestic violence in the new millennium: Intersectionality as a framework for social change. Violence against Women., 22(12), 1463–1475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215626808

Miller, C., Deckers, C., Jones, M., Wells-Beede, E., & McGee, E. (2021). Healthcare simulation standards of best practice outcomes and objectives. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.013

Miller, G. E. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 65(9), S63–S67. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045

Monrouxe. (2015). When I say... intersectionality in medical education research. Medical Education, 49(1), 21–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12428.

Morris, T. H. (2019). Experiential learning – A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(8), 1064–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279

Nascimento, J. D. S. G., Siqueira, T. V., Oliveira, J. L. G. D., Alves, M. G., Regino, D. D. S. G., & Dalri, M. C. B. (2021). Development of clinical competence in nursing in simulation: The perspective of Bloom’s taxonomy. Revista Brasileira De Enfermagem, 74(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0135

Nichols, S., & Stahl, G. (2019). Intersectionality in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Higher Education Research and Development, 38(6), 1255–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1638348

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place. The final report of the national inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. The National Inquiry. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2022.

*Overly, F. L., Sudikoff, S. N., Duffy, S., Anderson, A., & Kobayashi, L. (2009). Three scenarios to teach difficult discussions in pediatric emergency medicine: Sudden infant death, child abuse with domestic violence, and medication error. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 4(2), 114–130.https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0b013e318196f84d.

*Parameswaran, P., Moffa, J., Kim, D. J., Andrade, E. G., & Punch, L. J. (2021). Difficult conversations: Navigating intimate partner violence with standardized patients. The American Journal of Surgery, 221(2), 376–380.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.11.037.

Phillips, E., Strevens, C., & Grimes, R. (2016).Legal Education: Simulation in Theory and Practice. Taylor and Francis.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315592008.

Phrampus, P. E., & O’Donnell, J. M. (2013). Debriefing using a structured and supported approach. In A. I. Levine, S. De Maria, A. D. Schwartz, & A. J. Sim (Eds). The comprehensive textbook of healthcare simulation. Springer.

*Raja, S., Rajagopalan, C. F., Kruthoff, M., Kuperschmidt, A., Chang, P., & Hoersch, M. (2015). Teaching dental students to interact with survivors of traumatic events: Development of a two-day module. Journal of Dental Education, 79(1), 47–55.https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2015.79.1.tb05856.x.

*Richardson, K., & Speed, A. (2019). Promoting gender justice within the clinical curriculum: Evaluating student participation in the 16 days of activism against gender-based violence campaign. International Journal of Clinical Legal Education, 26(1), 87–131. https://doi.org/10.19164/ijcle.v26i1.823.

*Ritchie, M., Nelson, K., Wills, R., & Jones, L. (2013). Does training and documentation improve emergency department assessments of domestic violence victims? Journal of Family Violence, 28(5), 471–477.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9514-0.

Rochette. (2011). Teaching and learning in Canadian legal education: An empirical exploration. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Rochette, & Pue, W. W. (2001). “Back to basics”? University legal education and 21st century professionalism. The Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice, 20(SPEISS), 167.

*Salmon, D., Murphy, S., Baird, K., & Price, S. (2006). An evaluation of the effectiveness of an educational programme promoting the introduction of routine antenatal enquiry for domestic violence. Midwifery, 22(1), 6–14.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.002.

Savage, L. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Experiences of women with disabilities in Canada, 2018. Juristat, 1–23.

*Schillerstrom, J. E., Lutz, M. L., Ferguson, D. M., Nelson, E. L., & Parker, J. A. (2013). The women’s health objective structured clinical exam: A multidisciplinary collaboration. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 34(4), 145–149.https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482x.2013.846319.

*Schrier, M. W., Rougas, S. C., Schrier, E. W., Elisseou, S., & Warrie, S. (2017). Intimate partner violence screening and counseling: An introductory session for health care professionals. The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 13. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10622.

*Sedillo Lopez, A., Crandall, C., Campos, G., Rimple, D., Neidhart, M., McCarty, T., Clark, L., McLaughlin, S., & Martell, C. (2009). A medical/legal teaching and assessment collaboration on domestic violence: Assessment using standardized patients/standardized clients. International Journal of Clinical Legal Education, 14(14), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.19164/ijcle.v14i0.61.

*Shankar, M., Stevenson, M., Grant, N., &Akki, S. (2020). Addressing unmet needs in women’s health education for VA continuity clinic residents: A hands-on, resident-tailored curricular Innovation. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(1), S706.

*Shefet, D., Dascal-Weichhendler, H., Rubin, O., Pessach, N., Itzik, D., Benita, S., & Ziv, A. (2007). Domestic violence: A national simulation-based educational program to improve physicians’ knowledge, skills and detection rates. Medical Teacher, 29(5), e133–e138.https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701452780.

*Short, L. M., Cotton, D., & Hodgson, C. S. (1997). Evaluation of the module on domestic violence at the UCLAschool of medicine. Academic Medicine, 72(1), S75–S92.

*Short, L. M., Surprenant, Z. J., & Harris, J. M. (2006). A community-based trial of an online intimate partner violence CME program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(2), 181–185.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.012.

Skrundevskiy, A., Semin, J., Smith, L., & Rajaram, S. (n.d.). Report: Assessment of intimate partner violence education at UNMC. https://app1.unmc.edu/PublicAffairs/TodaySite/images/siteimages/IPV1205.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2022.

*Smith, R., Wight, R., & Homer, C. S. E. (2018). “Asking the hard questions”: Improving midwifery students’ confidence with domestic violence screening in pregnancy. Nurse Education in Practice, 28, 27–33.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.05.006.

*Sprague, S. (2019). A qualitative evaluation of the implementation of an intimate partner violence education program in fracture clinics. Journal of Family Violence, 34(7), 621–630.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00052-4.

*Stevens, N. R., Holmgreen, L., Hobfoll, S. E., & Cvengros, J. A. (2020). Assessing trauma history in pregnant patients: A didactic module and role-play for obstetrics and gynecology residents. AAMC Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 16, 10925. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10925.

Taft, A., Broom, D. H., & Legge, D. (2004). General practitioner management of intimate partner abuse and the whole family: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 328(7440), 618. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38014.627535.0b

*Thompson, R. S., Meyer, B. A., Smith-Dijulio, K., Caplow, M. P., Maiuro, R. D., Thompson, D. C., Sugg, N. K., & Rivara, F. P. (1998). A training program to improve domestic violence identification and management in primary care: Preliminary results. Violence and Victims, 13(4), 395–410.https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.13.4.395.

*Thornton, M., & Persuad, S. (2017). Enhancing understanding of intimate partner violence among undergraduate nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 56(4), 251.https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20170323-13.

*Trent, K., & Carlson, K. (2010). You want me to ask what? Making IPV inquiry relevant and practical to physical therapists. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 31(1).

University of Calgary. (2020). Experiential learning plan: 2020 –25. https://www.ucalgary.ca/provost/sites/default/files/teams/2/2020-25-UCalgary-Experiential-Learning-Plan-Digital.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2022.

Voyvodic, R. (2005). Lawyers Meet the Social Context: Understanding Cultural Competence. Canadian Bar Review, 84(3).

*Weiss, L. B., Kripke, E. N., Coons, H. L., & O’Brien, M. K. (2000). Integrating a domestic violence education program into a medical school curriculum: Challenges and strategies. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 12(3), 133–140.https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1203_3.

*Wong, S. L. F., Wester, F.,Mol, S. S., & Lagro-Janssen, T. L. (2006). Increased awareness of intimate partner abuse after training: A randomised controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice, 56(525), 249–257.

*Wong, S. L. F., Wester, F.,Mol, S., & Lagro-Janssen, T. (2007). "I am not frustrated anymore’’ family doctors’ evaluation of a comprehensive training on partner abuse. Patient Education and Counseling, 66(2), 129–137.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.013.

Wood, L. (2016). Simulation as a training tool for intimate partner violence screenings. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 12(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2015.11.001

World Health Organization. (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2022.

Young, A., & McFarlane, J. (1991). Preventing abuse during pregnancy: A national educational model for health providers. Journal of Nursing Education, 30(5), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-19910501-05

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a University of Calgary, Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Allison, A., Weerahandi, A., Johnson, T. et al. A Scoping Review on the Use of Experiential Learning in Professional Education on Intimate Partner Violence. J Fam Viol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00552-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00552-4