Abstract

Purpose

In England and Wales, Domestic Homicide Reviews (DHRs) are conducted into domestic abuse-related killings. In 2016, deaths by suicide were brought into the scope of this review system and, to distinguish them from reviews into domestic homicides, we describe these as ‘Suicide Domestic Abuse-Related Death Reviews’ (S-DARDR). To date, S-DARDRs have been little considered and, in response, this empirical paper seeks to unpack this process.

Method

In a larger study, 40 DHR participants were interviewed, and a reflexive thematic analysis was undertaken. 18 participants discussed S-DARDRs. These interviews were re-read, with relevant extracts identified and re-analysed thematically. Through a shared critical reflection, we drew on our practice experience to interrogate the themes generated from the interviews and offer insight into the underlying challenges.

Results

From the interviews, we generated four themes relating to commissioning and delivery; the involvement of stakeholders; intersections with other statutory processes; and purpose. Based on our shared critical reflection, we identified the underlying challenges as an under conceptualisation of S-DARDRs, alongside their de-mooring from the criminal justice system. Taken together, these challenges have implications for the conduct of S-DARDRs. We identify recommendations for policy and practice to address these challenges.

Conclusion

The development of S-DARDRs has been little considered and challenges arise around when and how they should be undertaken. A shared understanding of key concepts and expectations around delivery is necessary if S-DARDRs are to enable robust learning and be a driver for systems change while also being accessible and understood by all stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In England and Wales, in the three years to March 2020, there were some 362 victims of domestic homicide, of whom 276 (or 76%) were women (Office for National Statistics, 2021). Domestic homicide has consequently been the focus of considerable practice, policy, and academic attention. In contrast, domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide have received far less attention (Websdale, 2020). However, there is a strong association between the experience of domestic abuse and self-harm and suicidality (McManus et al., 2022). Tragically, some of these cases end in death, although pathways to suicide are “complicated and non-linear” (Munro & Aitken, 2020, p. 38), not least because suicide may be the consequence of multiple, intersecting risk factors and adverse events (McManus et al., 2022). Nonetheless, some estimates have suggested that a third of deaths by suicide of women may be at least partially attributable to domestic abuse (Walby, 2004), with men affected too (Monckton-Smith et al., 2022). Finally, according to the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) – which collected data on people aged 10 and over who died by suicide between 2009 and 2019 across the United Kingdom (U.K.) – of 5,218 patients who died by suicide while under care of the mental health system, an estimated 532 patients had experienced domestic abuse since data was collected from 2015 (Appleby et al., 2022, p. 6).Footnote 1 A link between domestic abuse and suicide has also been reported internationally (Devries et al., 2013; Kafka et al., 2022). Given the potential scale of domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide, it is crucial to examine and learn from these deaths to identify opportunities for prevention.

One way of generating learning about these deaths is through Domestic Violence Fatality Review (DVFR). First established in the United States, and now undertaken in multiple countries, DVFR – a general term that can be used to describe these review systems collectively, although their name varies by jurisdiction – is a collaborative process which brings stakeholders together to examine deaths that occur in the context of domestic abuse. By building a picture of these deaths, DVFR aims to identify practice, policy, or system learning, and thus prevent future tragedies (Websdale, 2020). The deaths considered vary between countries and, typically, DVFR systems consider intimate partner and often adult family homicides. However, one study reported that domestic abuse-related deaths by suicides – usually victim-focused – are also reviewed in just over half of extant review systems (Bugeja et al., 2017).

In England and Wales,Footnote 2 the DVFR system is known as Domestic Homicide Review (DHR). Principally encompassing reviews of intimate partner and adult family homicides, since 2016, deaths by suicide of a victim of domestic abuse have been included in the scope of the DHR process. However, referring to reviews of these deaths as ‘suicide DHRs’ would be an oxymoron, being both inaccurate and inappropriate. To address this, we draw on the model described by Fairbairn et al. (2019) to delineate the range of deaths that might occur in the context of domestic abuse and thus be subject to review. In this model, it is possible to distinguish between domestic homicides (which are the deaths otherwise encompassed by DHRs); domestic abuse-related homicides (which is where the role of the perpetrator and victim is shifted in some way, for example, where a victim of domestic abuse kills an abuser. These too are encompassed by DHRs); and domestic abuse-related deaths. With respect to domestic abuse-related deaths, these can encompass a wide range of deaths including those by suicide but also others like deaths stemming from health conditions or homelessness due to domestic abuse. Of these, to date, only deaths by suicide have been included in the scope of the review system in England and Wales and are thus our focus. Consequently, we describe this specific form of review as being ‘Suicide Domestic Abuse-Related Death Reviews’ (S-DARDRs).

Examining domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide is an opportunity to generate learning about these tragedies and some 70 S-DARDRs are estimated to have been completed (Monckton-Smith et al., 2022). Yet, the conduct of S-DARDRs has been little examined. Consequently, the question that this paper responds to is: what are the opportunities and challenges in undertaking S-DARDRs? To answer this question, the wider DHR system and the implementation of S-DARDRs are respectively described, and then methods and findings are presented. Thereafter, implications for S-DARDRs are discussed. Finally, research limitations, as well as recommendations for practice and policy, are noted. Throughout, we draw on the wider DVFR/DHR literature.

An Overview of the Review System in England and Wales

DHRs were introduced in section 9 of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act [DVCVA] 2004, although they did not become routine practice until implementation in 2011. Initially, DHRs encompassed domestic homicides (primarily killings by intimate partners and adult family members but also others i.e., by a lodger or flatmates). Since 2016, deaths by suicide of a victim of domestic abuse have also been reviewable (Home Office, 2016). Once a possible domestic homicide or a domestic abuse-related death by suicide has been identified – with this normally being by the police – the relevant local Community Safety Partnership (CSP) should be notified. CSPs – or ‘Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships’ – are statutory partnership bodies, established under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. In any given local area, a CSP includes the police, the local authority, fire and rescue authorities, health, and probation services (known as ‘responsible authorities’) and other local services. CSPs are responsible for reducing crime and disorder, substance misuse and re-offending in a local area. For a more detailed discussion of the role of CSPs generally, see Davies (2020) and, with respect to their role in DHRs, see Rowlands (2020).

Thereafter, if the case meets the criteria, a DHR/S-DARDR should be commissioned. In terms of process, an independent chair works with a multi-agency review panel, and testimonial networks (including family, friends, neighbours, and colleagues) may also be involved. As a product, a report is generated, detailing learning and any recommendations, with this then usually published. A developing literature addresses findings from the DHR/S-DARDR system in England and Wales, although largely the reported findings relate to DHRs (see, for example, Chantler et al., 2020; Sharp-Jeffs & Kelly, 2016).

Notably, DHRs/S-DARDRs have several differences to DVFR in other jurisdictions. First, nominally, a DHR/S-DARDR should be commissioned into every domestic homicide or domestic abuse-related death by suicide in scope but, as CSPs are not required to report on notifications or commissioning decisions, it is unclear if this is always the case (Rowlands, 2020). Second, a DHR/S-DARDR should be triggered when a domestic homicide or a domestic abuse-related death by suicide is identified. Consequently, a DHR/S-DARDR will normally commence in parallel to the criminal justice process, although it may be suspended or specific stages (such as engaging with testimonial networks who are also witnesses) may be deferred until any investigation and prosecution has been concluded. DHR/S-DARDR are also independent of coronial inquests and do not always align with them. Finally, DHR/S-DARDR are usually anonymously published as individual case reviews (Home Office, 2016).Footnote 3

The Implementation and Conduct of S-DARDRs

Initially, domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide were not reviewable, albeit their inclusion was considered (Home Office, 2006). Thus, the first two versions of the statutory guidance governing reviews in England and Wales did not refer to deaths by suicide and then did so as a type of death that was excluded (Home Office, 2011, p. 13, 2013, p. 14). Consequently, examining such deaths was at the discretion of the responsible CSP (Payton et al., 2017). However, when the third iteration of the statutory guidance was issued in 2016, deaths by suicide of a victim of domestic abuse were included in scope. A single paragraph was added to the statutory guidance which explained that deaths by suicide could be reviewed:

Where a victim took their own life (suicide) and the circumstances give rise to concern, for example it emerges that there was coercive controlling behaviour in the relationship, a review should be undertaken, even if a suspect is not charged with an offence or they are tried and acquitted. Reviews are not about who is culpable (Home Office, 2016, p. 8).

No rationale was given for this change nor was additional guidance provided. Consequently, given the limited explanation included in the statutory guidance, there are challenges as to how in-scope deaths by suicide are defined (Rowlands, 2020). At the time of writing, the statutory guidance has not been updated, so the definitional issue and the lack of guidance remain a challenge. Together, this means there is no robust framework for how S-DARDRs should be delivered, and challenges arise as to how these reviews should be identified, undertaken, described, and published. Illustratively, one study in London reported that CSPs wanted clearer guidance about S-DARDR commissioning (Montique, 2019).

Fortunately, the U.K. government’s recent Tackling Domestic Abuse Plan (hereafter, ‘the DA plan’) has recognised that, as part of proposals to reform DHRs, “more action is needed to better understand suicides that follow domestic abuse”, including the processes around S-DARDRs (HM Government, 2022, p. 69). In a small step toward addressing definitional issues, the DA plan expanded on the statutory guidance to describe the decision to conduct a S-DARDR as being based on the “presence of domestic abuse in a relationship of a person who has died”. The DA plan also confirmed that there is “no expectation that a [S-DARDR] should attempt to prove that a suicide was directly a result of domestic abuse” (HM Government, 2022, p. 69). While this further clarity is useful, nonetheless questions remain about both the definition of, and the lack of guidance for, S-DARDRs.

Having introduced the DHR/S-DARDR system in England and Wales, before presenting findings about the experiences and views of those involved in reviewing domestic abuse-related deaths, we first describe our method.

Method

This paper reflects a shared interest in DHR/S-DARDRs. JR is a doctoral researcher and a practicing independent chair. SD has previously worked for Advocacy After Fatal Domestic Abuse (AAFDA)Footnote 4 and sat on the national quality assurance panel.Footnote 5

The data used in this paper is derived from JR’s doctoral study, which examined the purpose, doing, and use of DHRs. First, the method for the larger study is set out. Second, an account of the development of this paper is presented.

Participants

The larger study involved DHR participants (of these, some had been involved in S-DARDRs). These participants included independent chairs and review panel members (including domestic abuse coordinators (DACs),Footnote 6 domestic abuse services, and other agency representatives from organisations like the police, health, and social services). Interviews were also conducted with testimonial networks (all family members), and family advocates (who provide specialist and expert advice to families involved in DHRsFootnote 7). Ethical approval was provided by Sussex University.

Procedure

In the larger study, participants had initially been recruited to take part in a web-based survey about their experiences of DHRs (of these, some had been involved in S-DARDRs) using a purposeful and snowballing recruitment strategy. These participants were then invited to a follow-up interview. Participants who expressed an interest were sent an information sheet with further information and, if they confirmed that they wanted to take part in an interview, were asked to sign and then return a consent form. 40 participants subsequently took part (38 consent forms were returned in advance of interviews, with two participants providing verbal consent). Subsequently, an interview was scheduled by phone or video conferencing software. Using an interview guide, interviews explored participant experiences. Each interview was audio-recorded. Thereafter, a verbatim transcript was prepared which, if they wished, participants could review and agree (a practice known as ‘Interviewee Transcript Review’). Pseudonyms were used to protect participant identities.

Data Analysis

For the larger study, reflexive thematic analysis was undertaken (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Familiarisation through multiple readings of the data was followed by coding and theme generation. NVivo was used for data management. For this paper, the analysis was revisited using suicide as a frame. The interviews were re-read by JR and extracts relating to suicide were identified and extracted. 18 participants discussed suicide. Participant involvement with DHRs/S-DARDRs is indicated on first use of their pseudonym. See Table 1.

By re-reading the identified extracts, JR generated themes through a close, interpretative reading across participants accounts. To explore these themes, JR approached SD as she had expertise in this area (including having secured funding to examine reviews of non-homicide domestic abuse-related deaths internationallyFootnote 8). Subsequently, JR and SD engaged in a recursive process of dialogue and writing, following the shared critical reflection approach described by Cullen et al. (2021). We drew on our practice experience of S-DARDRs – individually and as a system – to interrogate the themes generated from the interview data and to identify the underlying challenges. In the first phase, we each reflected individually on our experience. In the second phase, we reviewed and responded to each other’s reflections and produced a shared summary. In the final phase, we brought together our shared reflective summary with the themes generated by JR from the interview data.

Results

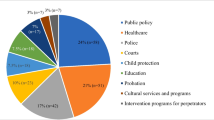

Four themes were generated from the interview data: (a) commissioning and delivering S-DARDRs is complicated (b) S-DARDRs involve stakeholders with different needs and perspectives (c) S-DARDRs intersect with other statutory processes (d) S-DARDRs have multiple purposes. See Fig. 1.

Commissioning and Delivering S-DARDRs is Complicated

Participants identified how, while being conducted under the same statutory guidance, S-DARDRs were different to DHRs. For Bobby (a family advocate), while DHRs into intimate or familial homicides had become common practice (despite only being undertaken routinely since 2011), reviewing deaths by suicide was an innovation that was less understood. This lack of understanding is reflective of the limited definition and guidance relating to S-DARDRs as described in the introduction. Indeed, because of the focus on domestic abuse-related death, ‘‘the whole dynamic… [of S-DARDRs] is different’’ (Joshua, an independent chair). The result was that commissioning and delivery were complicated.

Case Selection

Case selection involves the identification of domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide and the subsequent commissioning decision. When a potential domestic abuse-related death by suicide was identified, commissioning decisions could be complicated because it was not always clear if a case should be reviewed. Chloe (a DAC) noted:

We have also got one that is a suicide. You know, which is our… so I think they are very, very varied. And to do or not to do is very difficult. And none of them really neatly fit into the, or some do, but quite a lot don’t fit into the criteria.

While Chloe did not explicate this further, in context, she was referring to the challenge of making a judgement as to whether a S-DARDR should be commissioned, based on the criteria set out in the statutory guidance that a victim had both experienced domestic abuse and this, in some way, was sufficient to “give rise to concern”. Chloe further explained that the issue was not only about deciding whether a case was reviewable with reference to the criteria, but that case selection could also be on more instrumental grounds. Thus, Chloe highlighted the direct and indirect costs of S-DARDRs, which she felt might mean CSPs were reluctant to commission them.

Further explicating differences around case selection, Marie (a family advocate) reported variation in CSP decision making for other reasons. On one hand, Marie felt that some CSPs took a broader perspective and commissioned S-DARDRs having considered evidence of coercive control. Yet, she reported “some CSPs… will not consider this, especially where there is substance misuse”. Marie suggested this was because such deaths were treated as being by misadventure rather than being treated as a suicide, thereby potentially overlooking the connection - including the potential for coercion - between substance misuse and domestic abuse.

Finally, decision-making was also complicated in other ways. For example, Ella, a review panellist, said a victim’s former partner had challenged the commissioning decision, although the CSP proceeded against their wishes because they were the (alleged) perpetrator. Issues around family and (alleged) perpetrators are considered in the last theme.

Statutory Guidance

Inadequacies in the statutory guidance were identified as affecting commissioning decision making. Thus, although Chloe would consult the statutory guidance when making a commissioning decision, she felt “there is a lot of guidance missing”, including in respect to when a S-DARDR should be commissioned. Consequently, speaking about DHR/S-DARDR generally, Marie was concerned that this same lack meant: “They [CSPs] can use ambiguity to get out of… commissioning”.

Even if a S-DARDR was commissioned, the statutory guidance offered little advice as to its conduct and issues arose with various aspects of the processes to be followed, including the status and engagement of the (alleged) perpetrator. Overall, there was a sense that the statutory guidance needed to be developed. Referring to the limits of the framework for S-DARDRs, William (a review panellist) suggested: “I think that needs to be thought through at the Home Office [the sponsoring U.K. government department]. How are we going to deal with it?”

The Review Process

Some participants reflected on aspects of well-functioning DHR processes that were relevant to S-DARDR too. This included the value of police information at the start as this could help establish scope and/or understand family needs (Henry, an independent chair), as well as the importance of active organisational engagement (Victoria, a DAC, and Sophia, a domestic abuse specialist). Others highlighted challenges, like the absence of family information because “when you’re trying to understand what… [someone’s] background is, you do rely on the family” (Dylan, a review panellist).

A primary concern in undertaking an S-DARDR was access to information about the (alleged) perpetrator, with some participants highlighting how the absence of a conviction could be a barrier because organisations were less confident in the legal basis to share information:

So, when somebody is convicted of murder, you know, we need to see their information and medical records stuff, the DHR gives us that autonomy, if you like, of checking those records. That’s not the case when you’ve got somebody who’s suspected of domestic abuse that led to somebody’s suicide and they’re not convicted (William).

A further concern related to deliberation, particularly if there had been disagreement about the commissioning decision:

How you then kind of progress is really difficult because you’re potentially going to have some panel members that don’t think the review should be happening… that… makes it really difficult to get the best out of the [DHR/S-DARDR] and discussions (Bobby).

Other tensions emerged around causality and assessing the impact of domestic abuse on a victim’s death. Illustratively, Ella described one S-DARDR into the death of a man. In the discussions, the review panel struggled to disentangle what factors may have generally increased the victim’s risk of suicidality (i.e., because he was a man) with the specific impact of his experience of domestic abuse (i.e., whether this could be related in some way to his death). Conversely, Dylan – who, as a review panellist, represented a children’s services department – felt another DHR had inappropriately suggested that children’s services involvement, including a decision to implement a child protection plan, played a part in a victim’s death. Dylan had challenged this finding as inappropriate and had argued that the finding failed to take account of legislative requirements in this context, including a duty to protect children. We return to this point, including if and when a S-DARDR might be triggered based on organisational involvement, in the discussion.

S-DARDRs Involve Stakeholders with Different Needs and Perspectives

Professionals

For several participants, a key concern was training. When asked to lead a S-DARDR, Emma – who was an experienced independent chair, but had not previously reviewed a death by suicide – felt she had to seek out others who had done so to understand “how they had managed information sharing and things like that”. Likewise, Victoria sought external advice when first commissioning a S-DARDR. Notably, however, for both, this advice was ad-hoc rather than based on a clear framework for practice via training or in the statutory guidance.

A further issue was review panel knowledge. Bobby recalled a S-DARDR into the death by suicide of a woman from a specific community where there had been input from a ‘led by and for’ service. (I.e., services led by and for the communities they serve). In Bobby’s example, this was a specialist service that worked with Black and minoritized victim/survivors. Other examples included Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans+ (LGBT+) led by and for services. Without the involvement of a led by and for service, Bobby felt the review panel “just wouldn’t [have] be[en] able to relate to or understand” the victim, potentially limiting learning. Yet specialist knowledge was not always available or sought. For example, Alyssa (a DA specialist) and Ella had been involved in S-DARDRs involving male victims. For Alyssa, no men’s service was involved because none was available, while Ella acknowledged specialist expertise had not been considered.

Testimonial Networks

As already noted, there was a recognition of family roles in DHRs/S-DARDRs. In S-DARDR, there was a particular concern about the potential for trauma. For some, this arose because of the circumstances and death itself. Joshua was concerned that families might blame themselves following a suicide and Cora felt that a family had not participated in one S-DARDR for reasons of shame. Others were concerned about how a S-DARDR might affect the care of any children after a death, including the effect on kinship/other carers and/or safeguarding arrangements (i.e., where children’s services were involved with respect to assessing or meeting care and support needs). This might mean family could be reluctant to participate and/or have concerns about the publication of a report at a S-DARDR’s conclusion, especially if a child’s current caregiver was alleged to have been the abuser.

The (Alleged) Perpetrator

Participants identified a likely absence of a criminal justice outcome, specifically that the (alleged) perpetrator would not have been convicted in relation to a victim’s death and/or may not have previously been convicted of domestic abuse offences. As a result, a common concern was the (alleged) perpetrator’s status. First, in terms of their engagement, often “the perpetrator denies wholeheartedly any abuse” (Joshua). Second, contact was not always made with an (alleged) perpetrator, particularly if the victim’s family were against this. However, for some participants, this otherwise pragmatic decision raised concerns. Bobby was concerned about the absence of a perpetrator’s voice. For others, like Hazel (a review panellist), this meant a review might be less “rounded”. For both, the risk was a focus on the victim’s behaviour while the (alleged) perpetrator’s pathway to abuse went unexplored.

S-DARDRs Intersect with Other Statutory Processes

For S-DARDRs, participants noted intersections with other statutory processes that could be considering and/or involved with the same case. Key intersections included the criminal justice system, the coronial inquest, and child safeguarding arrangements.

Criminal Justice System

One concern was the likely absence of a criminal justice outcome, which might affect the legitimacy of a S-DARDR’s findings (not least because of the possible impact on information sharing, discussed above, and then publication, discussed below) but also leave family feeling justice had not been achieved. For some, this absence was itself illustrative of a broader lack of understanding and recognition of domestic abuse and suicide. Marie felt that the police sometimes inadequately investigated deaths by suicide and that this could potentially affect identification and commissioning decisions:

Friends have spoken about how the partner had… the victim had told the friend that his partner had said: “if you leave me, I am going to kill every family member of yours”. But the police have not even formally interviewed the partner.

For others, the issue was an unsatisfactory investigation outcome. Alyssa pointed to a S-DARDR which suggested the case was more appropriately described as an accidental death.

Finally, Joshua highlighted how testimonial network members and the (alleged) perpetrator might be witnesses to or the subject of an ongoing criminal investigation after a death. For example, such an investigation might be into alleged coercive control which had come to light before or following a victim’s death. Such evidence-led investigations are not dependent on the victim being alive if other evidence is available (e.g. statements from other witnesses, closed circuit television (CCTV) evidence or 999 recordings). This, Joshua emphasised, presented procedural challenges if a S-DARDR was also running in parallel.

Coronial Inquest

Given the likely absence of a criminal justice outcome, the coronial process was particularly relevant. William, talking generally about DHRs/S-DARDRs, felt that coroners would take a “very keen interest” in any findings, whether they related generally to organisational contact or specifically to domestic abuse, including using these to inform an inquest. For others, wider potential benefits followed if a coroner recorded a finding that might speak to someone’s experience of domestic abuse:

I mean, if [the DHR] helps us to get an inquest result that says that [our loved one] died by suicide as a result of domestic abuse then I’ve schooled my expectations to be satisfied with that (Luna, family member).

But I was at the inquest last week. Very old school coroner, who said there wasn’t enough evidence… [but] he said if further evidence comes to light within the DHR or any other way, then he would go to the chief coroner to reopen the inquest but concluded it was suicide (Marie).

Yet, this was also a source of potential concern. For example, Joshua – a former police officer – suggested independent chairs might be called to give evidence, meaning S-DARDRs would then be brought directly into the scope of the coronial inquest. As an independent chair, JR has given evidence in a coroner’s court, and SD is aware of another having done so too.

Child Safeguarding Arrangements

Several participants noted safeguarding arrangements for children. Sophia suggested that child safeguarding arrangements, whereby children’s services are directly involved with a family after a death, could assist S-DARDRs. For Sophia, this was because “they really brought… [the] child’s voice”, with this potentially facilitated via social workers who were working with any children. Yet safeguarding arrangements could also be a barrier if children were in the care of the surviving parent who was also the (alleged) perpetrator of abuse. This could mean a victim’s family felt unable to participate:

[The family do not want to talk to us] I think for all sorts of reasons, but partly because [the family member] doesn’t want to jeopardize access [to the child] (Victoria).

Even if children were not in the (alleged) perpetrator’s care, their presence could still be felt. Luna reported that as the (alleged) perpetrator lived in the same area as the children, their kinship carers, and other family, a request was made that the report not be published because “it was thought to be safer” for those directly involved.

S-DARDRs Have Multiple Purposes

In the larger study, participants noted the multiple, overlapping and sometimes conflicting views as to DHR/S-DARDRs’ purpose, which could affect how stakeholders engaged in these processes and/or their expectations for them. For S-DARDRs, purpose could include telling a victim’s story. This story telling could include locating a victim’s experiences more broadly which, for Hazel, included recognising the impact of past domestic abuse and the intersection with issues like mental health and alcohol use. However, storytelling could also personalise any account, with Luna emphasising how, as a family member, she hoped that a S-DARDR might tell her loved one’s story. Similarly, Marie hoped that a S-DARDR might offer “the only glimmer of light for the family” in describing what happened. Others emphasised S-DARDRs as a learning tool that might bring about practice, policy, and system changes. Discussing a S-DARDR, Victoria said:

It’s awful to say this - but it feels like it’s come at an opportune moment because there’s quite a lot in there about how children’s services work in relation to domestic abuse. It feels like we’ve just got to a point where we’re having that proper conversation with children’s services and so… the case itself illustrates various of the issues that we’ve been talking about for quite a long time… it helps, kind of, focus minds on those issues.

Finally, some participants emphasised the importance of dissemination, including through the publication of a report at a S-DARDR’s conclusion. Yet, challenges arose. First, as noted above, there was likely not a convicted perpetrator. William felt this absence affected reports because: “writing those reports up is very difficult when there may not be any criminal charges coming thereafter”. This was because a report had to be couched in terms of allegations and/or some information could not be included for this same reason. Second, as discussed in the context of safeguarding, publication raised the question of what would happen with information in the public sphere. For example, as noted above, Luna’s family successfully argued against publication because the perpetrator lived locally.

Discussion

A key finding is the potential for S-DARDRs to produce learning from domestic abuse-related deaths and thereby identify changes to practice, policy, and systems; to tell a victim’s story; and to be meaningful to family. Whether S-DARDRs (and DHRs generally) deliver this is beyond this paper’s scope, however, S-DARDRs could be a way of “shining light” onto cases that might otherwise be little considered (Payton et al., 2017, p. 115). Therefore, S-DARDRs may also contribute to the recognition of the long-term impact of domestic abuse which, given the gendered dimensions of deaths by suicide, could be considered “slow femicides” (Walklate et al., 2020).

However, there has been inadequate consideration of the implications of implementing S-DARDRs. This is literally manifested in the current statutory guidance, which has only one paragraph specifically relating to S-DARDRs (Home Office, 2016, p. 8). Yet, generally, DHRs have been recognised as complex and challenging (Haines-Delmont et al., 2022). Based on the findings here, S-DARDRs are potentially even more so. To explore this further, we structure the discussion around the underlying challenges identified from our shared critical reflection: first, an under conceptualisation of S-DARDRs, and second, their de-mooring from the criminal justice system. We address each challenge in turn, before identifying the implications for S-DARDRs’ conduct (including how they should be undertaken, described, and published), and making policy and practice recommendations.

S-DARDRs are Under Conceptualised

Unsurprisingly, several participants reported struggles with, crassly put, which deaths by suicide count. This is because domestic abuse-related deaths can be difficult to identify (Fairbairn et al., 2019). First, it can be difficult to determine what role domestic abuse may have played in a death by suicide (Jones et al., 2022). This is because, while there are established links between domestic abuse and suicidality, a direct causal contribution is hard to establish (McManus et al., 2022; Munro & Aitken, 2020). Second, the significance of domestic abuse in a death by suicide can be overlooked. Illustratively, Monckton-Smith et al. (2022) have suggested that a mental health history (particularly suicide ideation) may be taken as a sufficient explanation for a death, affecting any police investigation and leading them to overlook evidence of domestic abuse. Taken together, these issues make the identification of cases challenging.

Moreover, even if identified, cases must be referred. In DHRs/S-DARDRs, the police are the most common referrer, but it is not clear whether all cases – assuming they are identified – are referred and, if not, the reasons for this. However, emerging evidence suggests that identification and referral may be improving. For example, over the two years to the end of March 2022, where data was available, the police in England and Wales identified and referred 97 suspected domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide. Broken down by year, 39 cases were referred in year one, with this increasing to 58 in year two. Yet, while the study authors highlight both a high identification rate and evidence of improvement, they nonetheless caution that it remains possible that some cases are not being referred for review (Bates et al., 2022b).

Consequently, to support identification, robust mechanisms are needed to identify possible domestic abuse-related deaths. It is therefore welcome that the DA plan has committed to “identify best practice in identifying appropriate suicide cases to be referred” (HM Government, 2022, p. 69). However, this commitment is made in relation to policing. While the police have an important role to play, public health must be recognised as a key stakeholder (and, of course, domestic abuse services). Yet, in this respect, the DA plan makes only generalised reference to public health, despite its central role in suicide prevention (e.g., see HM Government, 2012). Developing more robust mechanisms to identify and then refer deaths for consideration for a S-DARDR is essential. One model can be found in Kent and Medway, where domestic abuse has been included as a priority in the local Suicide Prevention Strategy and, to better identify potentially referrable deaths (including for victims and (alleged) perpetrators), a specific question about domestic abuse has been included in the data collection process used as part of the local Real-Time Suicide Surveillance system (Woodhouse, 2021). Meanwhile, in respect of decision-making, in Gloucestershire, a protocol supports case identification and then onward referral for a commissioning decision (Safer Gloucestershire, 2022).

Yet, even if a domestic abuse-related death by suicide is identified and then referred to the relevant CSP, a commissioning decision must still be made. To support this, S-DARDRs need to be more fully conceptualised. Currently, S-DARDRs can be undertaken “where a victim took their own life (suicide) and the circumstances give rise to concern” and evidence of coercive control is given as an example of such concern (Home Office, 2016, p. 8). However, this scant definition raises more questions than it answers. Consequently, without better conceptualisation, CSPs may continue to make different commissioning decisions, a finding supported by the data presented here about the challenges of working with inadequate guidance or, more problematically, the desire to avoid commissioning a S-DARDRs. This may be because of, for example, the direct or indirect cost of commissioning a S-DARDRs (Bates et al., 2022a), or because there is a belief nothing might be learnt about domestic abuse because of limited agency contact (Rowlands & Bracewell, 2022). In the absence of published data on DHR/S-DARDR decision-making, it is not possible to explore this further. However, the previously mentioned study by Bates et al. (2022b) suggests a mixed, albeit broadly positive, picture for police referrals. Of the 97 deaths by suicide referred by the police for review, 60% (n = 58) were accepted and only 6% (n = 6) four had been rejected. However, conversely, a decision had not been made in 32% (n = 31) of cases, with an increase in cases awaiting a decision in year two. While the study authors were not able to comment further on this trend, they suggested that – in addition to their previously mentioned concern that some cases were not being identified – other cases may be referred but then not reviewed. The authors suggest that this was because of the discretion that can be exercised by CSPs, in the light of the inadequacies of the statutory guidance, which means some might engage in ‘‘screening’’ (Bates et al., 2022b, p. 96).

To address this under conceptualisation, two key questions have been posed. First, is any history of domestic abuse sufficient and how must this be evidenced? Second, must there be a direct connection and, if so, how proximate must this be? (Rowlands, 2020; Rowlands & Bracewell, 2022). The U.K. government’s answer to these two questions is respectively ‘yes’ and ‘no’ given, as noted in the introduction, the DA plan states that – with respect to commissioning a S-DARDR – the key issue is a history of domestic abuse and there is no expectation of a direct connection between that history and a death (HM Government, 2022, p. 69). Nonetheless, the conceptualisation of a S-DARDR remains unclear both in terms of the scope of deaths included and the threshold for decision.

Concerning scope, three key questions arise. (1) Who can provide evidence of a history of abuse? Our view is that this should include both organisations and/or testimonial networks, particularly as disclosures may be made to the latter and not the former (Websdale, 2020). (2) What timeframe should be considered? As there is evidence of increased suicidality among both those subject to lifetime and in-year abuse (McManus et al., 2022), we suggest that any timeframe should be extended, as setting a short timeframe might exclude relevant cases. (3) What relationships are in scope? To fully consider the impact of domestic abuse, we propose it should be possible to consider both a victim’s recent and previous relationships (thus encompassing past experiences of abuse too).

In terms of threshold, basing commissioning decisions on whether a death by suicide “give[s] rise to concern” is problematic, given this is little defined and therefore subjective. Further explication, building on the clarification in the DA plan, is therefore necessary to enable more consistent decision-making. We argue that the threshold for S-DARDR should focus on connection, specifically whether a death is “related to, or somehow traceable to” domestic abuse (Websdale, 2020, p. 1). A concern with connection would enable commissioning decisions to be informed by questions of scope and the breadth of possible case circumstances. Consider the following hypothetical example. Children can be a protective factor vis-à-vis suicidality (Aitken & Munro, 2018). Yet, in some cases, if one parent is abusive, child protection interventions may need to be undertaken, including those that see a child removed from the household. While such a removal may be necessary, this may leave the non-abusive parent/victim feeling an increased sense of “entrapment or hopelessness” (Monckton-Smith et al., 2022, p. 25). Such a sense of entrapment or hopelessness may arise if the non-abusive parent/victim’s needs after removal were left unaddressed or if this experience limited their confidence or capacity to seek help for domestic abuse. If the non-abusive parent subsequently died by suicide, a concern with connection would mean that this scenario could be considered a meaningful example of domestic abuse-related suicide and thus trigger the commissioning of S-DARDR. Understanding threshold in this way would enable the consideration of victim experience, the (alleged) perpetrator’s role, and the impact of state (in)action if appropriate.

In summary, a definition of S-DARDR should be developed to provide a framework for commissioning decisions based on scope and threshold. Rather than setting arbitrary decision-making points (e.g., reports within a set timeframe), this definition should be normative, including possible factors to consider when making a commissioning decision.

However, given the potential scale of domestic abuse-related suicides that could be captured within a revised definition, it is important to consider the implications. While concerns about the funding of DHR/S-DARDR have been reported (Montique, 2019), notably the DA plan neither addresses the potential number of S-DARDRs nor the consequent resource requirement. However, the total number could be considerable, as suggested by the summary provided at the start of this paper. A discussion of how S-DARDRs (and DHRs) should be resourced is essential, including if resourcing limitations can be considered when making commissioning decisions (particularly given the direct and indirect costs of reviews are, respectively, largely borne by commissioning CSPs and participating organisations). Any discussion must recognise the implications of under-resourcing, including the potential impact of decisions not to commission, not least on a family (Haines-Delmont et al., 2022).

S-DARDRs are (Usually) De-Moored from the Criminal Justice System

As already noted, in a S-DARDR there will often not be a convicted perpetrator, albeit this may change if the criminal justice system begins to routinely consider culpability (Munro & Aitken, 2018). Thus, effectively, S-DARDRs – unlike DHRs – are usually de-moored from the criminal justice system. Moreover, while a coroner may reach a verdict of suicide where there is sufficient evidence to suggest a victim intended to take their own life, such a determination may be challenging in terms of establishing a domestic abuse link (Jones et al., 2022). However, as with criminal justice, this may change: a coroner recently made this link when, for the first time in a coronial inquest, domestic abuse was identified as having a causal role in the death of Jessica ‘Jessie’ Laverack (Keynejad et al., 2022).

In this light, a key finding is the extent to which these absences can impact S-DARDRs, particularly around the extent to which an (alleged) perpetrator can be identified or a determination as to their responsibility made, and here guidance is limited (Home Office, 2016, p. 19). This raises several issues. First, should the (alleged) perpetrator be notified and/or engaged in the S-DARDR and, if so, how? The involvement of (alleged) perpetrators might raise concerns about their potential use of this process to justify their behaviour or further abuse (Rowlands & Cook, 2022). Thus, in a recent study, families revealed concerns that the (alleged) perpetrator could exert control over the timeline of S-DARDRs and, in the absence of the victim’s voice, also influence the content of the subsequent report (Dangar et al., forthcoming). Moreover, engaging an (alleged) perpetrator could present a risk if they made threats to family members when the victim was alive and/or if family participation becomes known. Illustratively, we both know of families who have been fearful of/have experienced harassment by an (alleged) perpetrator and, in some cases, have sought restraining orders. This potential risk has also been noted by Monckton-Smith et al. (2022).

There are then several difficulties around perpetrator engagement that may affect the information available to S-DARDRs. In our view, the extension of the statutory guidance to include domestic abuse-related deaths without explicitly addressing these issues was problematic. It has meant that those delivering S-DARDRs have had to manage these issues without adequate guidance and so there is the potential for differences in operationalisation and, critically, risk. Consequently, it is perhaps understandable that independent chairs and review panels choose not to engage with (alleged) perpetrators with a consequent impact on the potential for learning around their behaviours and any opportunities for interventions.

Implications for Conducting S-DARDRs

Given these underlying challenges, what are the implications for conducting S-DARDRs? In DHRs, the skills and experience of the independent chair and review panel, the involvement of testimonial networks, and publication/dissemination are critical (see Haines-Delmont et al. (2022) for a discussion). The findings here, both from the interview data and our shared critical reflections, echo these concerns with respect to S-DARDRs.

The Review Panel

While review panels should be “sufficiently configured to bring relevant expertise” (Home Office, 2016, p. 11), DHRs are potentially affected by the inadequacies of the current competencies and training framework for independent chairs and review panellists (Rowlands, 2020). This could be exacerbated in a S-DARDR, particularly given the aforementioned challenges regarding both identifying and then understanding the part and significance domestic abuse may have played. Thus, in a S-DARDR, review panels need access to appropriate expertise including from mental health services, whose input may be necessary to identify the (in)adequacy of mental health responses (Trevillion et al., 2014). Looking beyond mental health services, review panels should include public health specialists to provide a link to local suicide prevention initiatives and assist in the understanding of the complex nature of suicide and suicidality and any agency responses (or lack thereof).

Yet, other expertise may also be needed, including from other specialist services. In the findings, one example illustrated how led by and for specialist services helped a review panel situate a victim’s experience in a cultural context (Siddiqui & Patel, 2010). Conversely – and reflecting findings elsewhere (Snowball & Rowlands, 2019) – services with male expertise were absent. Together, these examples speak to the potential value of a broad review panel membership (Websdale, 2020). Such breadth should include specialist services – including led by and for services – who can bring knowledge and expertise relating to a victim’s specific experiences and needs (Jones et al., 2022; Montique, 2019), for example around the impact of migration. There is therefore a need to consolidate best practices in the constitution of review panels.

Testimonial Networks

The involvement of testimonial networks, particularly family members, is an essential but potentially challenging aspect of review. The findings are further evidence of this tension. Some families may welcome a S-DARDRs, and their potential contribution to and benefit from DHRs/S-DARDRs can be considered broadly in terms of relational and systems repair (Rowlands & Cook, 2022). Yet, there may simultaneously be concerns. For example, the experience of stigma by those bereaved by suicide is associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour and depression (Pitman et al., 2017). This underlines the necessity of access to expert and specialist advocacy support for families, with this both supporting participants specifically during a review but also enquiring about, helping identify, and then addressing any wider support needs.

Second, language needs to be considered. Indeed, our decision to use the terminology of S-DARDRs is because describing someone’s death by suicide as a DHR is inaccurate and inappropriate: it may feel particularly so in our experience for families. Here, the Home Office Leaflet for Family MembersFootnote 9, which refers only to domestic homicide, is insensitive. Like us, some CSPs have begun to refer to S-DARDRs. However, some may feel that ‘domestic abuse’ is problematic, perhaps because of challenges in terms of family feelings, or because of issues regarding the (alleged) perpetrator. To navigate this, one area known to SD refers to ‘Multi-Agency Reviews’. While this vagary manages potential challenges, it also ceases to situate these deaths as domestic abuse related. Our view is that S-DARDR is the least bad option because it recognises that these deaths are not homicides without obscuring domestic abuse. However, further consideration is required as to the most appropriate and accessibly terminology, not least because while S-DARDR may be accurate it is an awkward term for everyday use.

Third, the broader literature has identified sensitivities in the care of children after a domestic homicide (Alisic et al., 2017), including around if and how they should be involved in DHRs (Haines-Delmont et al., 2022). Such sensitivities are present in S-DARDRs; Indeed, they may be magnified, given the issues identified here around how the safeguarding of children, particularly in a S-DARDR, could impact on family relationships and/or reveal information that might affect caring arrangements. The findings also point to the intersections between S-DARDRs and other statutory processes, highlighting the need for clear communication and working arrangements between them.

Publication and Analysis

As noted, S-DARDRs (and DHRs) are case-specific, and an anonymised report is usually published. The findings have highlighted some of the challenges around the publication of S-DARDRs, both in terms of family impact, but also concerning the use of (alleged) perpetrator information. Publication may also present a risk to professionals, who must be named in the report (Home Office, 2016, p. 11). Together, these issues may mean that, having conducted a S-DARDR, CSPs err on the side of caution at its conclusion and choose not to publish (H. Candee, personal communication, November 8, 2021).

While understandable, non-publication limits the dissemination of S-DARDR learning, minimising impact. Meanwhile, given the growing number of S-DARDRs, there is an opportunity to share learning in aggregate. To date, the absence of a national repository to hold DHRs/S-DARDRs has been identified as a significant concern (Montique, 2019; Sharp-Jeffs & Kelly, 2016), despite being long recommended as a tool to aid learning (Jones et al., 2022). However, as part of the DA plan, a repository is being developed (HM Government, 2022), although its final shape and functionality remain unclear. A repository could address some of the specific difficulties with publication: If there was a concern about local publication, it could publish a suitably de-identified S-DARDR report in full.Footnote 10 Ideally, a repository would also enable the regular review of S-DARDRs, including the routine aggregation and analysis of findings (Rowlands & Bracewell, 2022). An example of the potential value of such analysis has been demonstrated by a report released by the Home Office about 124 DHRs submitted for quality assurance in the 12 months from October 2019, including 14 S-DARDRs (Potter, 2022). The potential of aggregation is evident then, as this would enable the dissemination of learning more broadly, driving improvements in practice and policy responses, as well as being a means to share best practice in S-DARDRs’ conduct.

Recommendations for Developing Practice and Policy

While the scale of domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide, and the tragedy each of these deaths represent, means S-DARDR has an important role to play, we have argued that their conduct is challenging. Considering the findings and discussion, we make the following practice and policy recommendations:

Practice Recommendations

-

1.

Drawing on both criminal justice and public health data, develop local mechanisms to identify and refer domestic abuse-related deaths by suicide for a commissioning decision.

-

2.

Ensure the skills and knowledge of the independent chair and review panel are tailored to each case (including involving domestic abuse, led by and for, and other specialist services).

-

3.

Ensure that the family have equal status. This must include identifying and addressing the specific issues and support needs that may arise in decision-making around, participation in, and support following S-DARDRs.

-

4.

Develop a publication and dissemination strategy to ensure that learning from S-DARDRs can be safely shared regardless of decisions around publication.

Policy Recommendations

-

1.

Agree on a more appropriate terminology, for example and as suggested here, S-DARDRs.

-

2.

Develop a normative definition to guide decision-making concerning the scope and threshold of deaths by suicide that should be subject to S-DARDR.

-

3.

Review the resourcing for S-DARDRs to ensure consistency of commissioning.

-

4.

Develop a training/competencies framework for independent chairs and review panellists.

-

5.

Map the intersections between S-DARDRs and other statutory processes to understand challenges and opportunities, in particular for coronial inquests and child safeguarding.

-

6.

Revise the statutory guidance and associated documents to address the commissioning, practice, and publication issues that arise in S-DARDRs.

-

7.

Ensure the national repository supports the dissemination of learning from S-DARDRs, both individually and in aggregate.

Limitations and Future Research

The paper makes an important contribution because it is the first to specifically address S-DARDRs. However, the findings are based on a convenience sample of a subset of participants from a larger study and so further research is needed to generate and explore richer data about participant experiences. Further research into the findings of S-DARDRs specifically, including differences in experiences (e.g., in terms of age, sex/gender, sexual orientation, etc.), as well as findings (e.g., around service responses), would also improve our understanding of these deaths and the opportunities for practice, policy and system change.

Additionally, some issues have not been explored here, notably the death by suicide of perpetrators. Currently, a S-DARDR can only be triggered by, and will focus on, a victim’s death. Thus, as has been observed elsewhere, while deaths by suicide of (alleged) perpetrators are potentially significant they are underexamined (Websdale, 2020). Such an examination might include deaths already identified in DHR/S-DARDRs. For example, the (alleged) perpetrator died by suicide in 11 of 124 DHR/S-DARDRs submitted for quality assurance in the year from October 2019 (all but one of whom was a man) (Potter, 2022). Yet, more broadly, deaths by suicide of (non-homicidal) perpetrators are a significant issue (Kafka et al., 2022). If and how these deaths might be reviewed should be further explored.

Finally, it would also be valuable to compare the policy and practice issues for S-DARDRs to those in other DVFR systems. This would enable consideration of whether the findings and recommendations made here have relevance to other jurisdictions. Such consideration would also enable the exploration of data collaboration across DFVR systems.

Conclusion

The paper has considered S-DARDRs. In seeking to unpack S-DARDRs, although there is clearly a rationale and benefit in undertaking them, we have identified some of the challenges in their doing. We have argued these challenges arise because S-DARDRs are under-conceptualised and de-moored from the criminal justice system. Importantly, while sharing similarities with DHRs following intimate, familial, and household member domestic homicides, S-DARDRs are also distinct. The U.K. government has proposed to address S-DARDRs as part of a package of DHR reform, and this is welcome. Moving forward, a shared understanding of key concepts and expectations around delivery is vital if S-DARDRs are to be conducted well and, critically, in a way that is accessible and understood by all stakeholders including family. This is important too more broadly, particularly so S-DARDRs can be used as a robust source of learning and a driver for systems change.

Notes

These data are for England and Wales, but also Northern Ireland and Scotland. These data include men and women and some of these patients, proportionally more men, had a history of violence as a perpetrator.

DHRs have also recently been introduced in Northern Ireland but are not yet undertaken in Scotland.

Provides expert and specialist and expert advocacy for families. See: https://aafda.org.uk/.

Convened by the Home Office with responsibility for quality assuring DHR/S-DARDRs prior to publication.

Refers generically to a role where the post holder has responsibility for coordinating local responses to domestic abuse and sometimes other forms of violence against women and girls.

In addition to AAFDA, the other organisation which provides support is the Victim Support Homicide Service (VSHS). See: https://www.victimsupport.org.uk/more-us/why-choose-us/specialist-services/homicide-service/.

The national repository for reviews into the serious injury or death of children already does this. See: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/case-reviews.

References

Appleby, L., Kapur, N., Shaw, J., Turnbull, P., Hunt, I. M., Ibrahim, S., & Burns, J. (2022). Annual report: UK patient and general population data, 2009–2019, and real time surveillance data. The National Confidentiality Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health. https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/reports/annual-report-2022/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Aitken, R., & Munro, V. E. (2018). Domestic abuse and suicide: Exploring the links with Refuge’s client base and work force. Refuge. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/103609/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Alisic, E., Groot, A., Snetselaar, H., Stroeken, T., & van de Putte, E. (2017). Children bereaved by fatal intimate partner violence: a population-based study into demographics, family characteristics and homicide exposure. PLoS One, 12(10), e0183466. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183466

Bates, L., Hoeger, K., Nguyen Phan, T. T., Perry, P., & Whitaker, A. (2022a). Domestic homicide project—Spotlight briefing 5—Suspected victim suicide following domestic abuse. Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme. https://www.vkpp.org.uk/publications/publications-and-reports/. Accessed 7 Fb 2023.

Bates, L., Hoeger, K., Nguyen Phan, T. T., Perry, P., & Whitaker, A. (2022b). Domestic homicides and suspected victim suicides 2021–2022: Year 2 Report. Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme. https://www.vkpp.org.uk/publications/publications-and-reports/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: a practical guide to understanding and doing (1st ed.). SAGE Publications.

Bugeja, L., Dawson, M., McIntyre, S. J., & Poon, J. (2017). Domestic/family violence death reviews: an international comparison. In M. Dawson (Ed.), Domestic homicides and death reviews: an international perspective (pp. 3–26). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chantler, K., Robbins, R., Baker, V., & Stanley, N. (2020). Learning from domestic homicide reviews in England and Wales. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(2), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12881

Cullen, P., Dawson, M., Price, J., & Rowlands, J. (2021). Intersectionality and invisible victims: Reflections on data challenges and vicarious trauma in femicide, family and intimate partner homicide research. Journal of Family Violence, 36(5), 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00243-4

Dangar, S., Munro, V. & Young Andrade, L. (forthcoming). Learning legacies: An analysis of domestic homicide reviews in cases of domestic abuse suicide. Home Office.

Davies, P. (2020). Partnerships and activism: Community Safety, multi-agency partnerships and safeguarding victims. In J. Tapley, & P. Davies (Eds.), Victimology (pp. 277–299). Palgrave Macmillan.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Bacchus, L. J., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Petzold, M., & Watts, C. H. (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439

Fairbairn, J., Sutton, D., Dawson, M., & Jaffe, P. (2019). Putting definitions to work: reflections from the canadian domestic homicide prevention initiative with vulnerable populations. In Sociological studies of children and youth (Vol. 25, pp. 67–82). https://doi.org/10.1108/S1537-466120190000025005

Haines-Delmont, A., Bracewell, K., & Chantler, K. (2022). Negotiating organisational blame to foster learning: professionals’ perspectives about domestic homicide reviews. Health & Social Care in the Community, Hsc.13725. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13725

HM Government (2012). Preventing suicide in England: a cross-government outcomes strategy to save lives. Department of Health. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-strategy-for-england. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

HM Government (2022). Tackling domestic abuse plan. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tackling-domestic-abuse-plan. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Home Office (2006). Guidance for domestic homicide reviews under the domestic violence, crime and victims act 2004. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090804170644/http://www.crimereduction.homeoffice.gov.uk/domesticviolence/domesticviolence62.htm. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Home Office (2011). Multi-agency statutory guidance for the conduct of domestic homicide reviews. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/97881/DHR-guidance.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Home Office (2013). Multi-agency statutory guidance for the conduct of domestic homicide reviews https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150402141623/https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/revised-statutory-guidance-for-the-conduct-of-domestic-homicide-reviews. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Home Office (2016). Multi-agency statutory guidance for the conduct of domestic homicide reviews. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/575273/DHR-Statutory-Guidance-161206.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Jones, C., Bracewell, K., Clegg, A., Stanley, N., & Chantler, K. (2022). Domestic homicide review committees’ recommendations and impacts: A systematic review. Homicide Studies, 108876792210817. https://doi.org/10.1177/10887679221081788

Kafka, J. M., Moracco, K., Beth, E., Taheri, C., Young, B. R., Graham, L. M., Macy, R. J., & Proescholdbell, S. (2022). Intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration as precursors to suicide. SSM - Population Health, 18, 101079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101079

Keynejad, R. C., Paphitis, S., Davidge, S., Jacob, S., & Howard, L. M. (2022). Domestic abuse is important risk factor for suicide. BMJ, o2890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o2890

McManus, S., Walby, S., Barbosa, E. C., Appleby, L., Brugha, T., Bebbington, P. E., & Knipe, D. (2022). Intimate partner violence, suicidality, and self-harm: a probability sample survey of the general population in England. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(7), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00151-1

Monckton-Smith, J., Siddiqui, H., Haile, S., & Sandham, A. (2022). Building a temporal sequence for developing prevention strategies, risk assessment, and perpetrator interventions in domestic abuse related suicide, honour killing, and intimate partner homicide. University of Gloucestershire. https://doi.org/10.46289/RT5194YT. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Montique, B. (2019). London Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) case analysis and review of local authorities DHR process. Standing Together Against Domestic Abuse. https://www.standingtogether.org.uk/dhr. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Munro, V., & Aitken, R. (2018). Adding insult to injury? The Criminal Law’s response to domestic abuse-related suicide in England and Wales. Criminal Law Review, 9, 732–741.

Munro, V. E., & Aitken, R. (2020). From hoping to help: identifying and responding to suicidality amongst victims of domestic abuse. International Review of Victimology, 26(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758018824160

Office for National Statistics (2021). Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: Year ending March 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2021. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Payton, J., Robinson, A., & Brookman, F. (2017). United Kingdom. In M. Dawson (Ed.), Domestic homicides and death reviews: an international perspective (pp. 91–123). Palgrave Macmillan.

Pitman, A., Rantell, K., Marston, L., King, M., & Osborn, D. (2017). Perceived stigma of sudden bereavement as a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and suicide attempt: analysis of british cross-sectional survey data on 3387 young bereaved adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030286

Potter, R. (2022). Domestic homicide reviews: Key findings from analysis of domestic homicide reviews. Home office. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/key-findings-from-analysis-of-domestic-homicide-reviews. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Rowlands, J. (2020). Reviewing domestic homicide—International practice and perspectives. The Churchill Fellowship. https://www.churchillfellowship.org/ideas-experts/ideas-library/reviewing-intimate-partner-homicide-international-practice-and-perspectives. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Rowlands, J., & Bracewell, K. (2022). Inside the black box: domestic homicide reviews as a source of data. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 6(3), 518–543. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868021X16439025360589

Rowlands, J., & Cook, E. A. (2022). Navigating family involvement in domestic violence fatality review: Conceptualising prospects for systems and relational repair. Journal of Family Violence, 37(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00309-x

Safer Gloucestershire (2022). Gloucestershire Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) Protocol: Appendices. http://www.glostakeastand.com/professionals/guidance/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Sharp-Jeffs, N., & Kelly, L. (2016). Domestic homicide review (DHR) case analysis. Standing Together Against Domestic Abuse and London Metropolitan University. https://www.standingtogether.org.uk/dhr. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Siddiqui, H., & Patel, M. (2010). Safe and sane: a model of intervention on domestic violence and Mental Health, suicide and self-harm Amongst Black and Minority ethnic women. Southall Black Sisters. https://store.southallblacksisters.org.uk/safe-and-sane-report/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Snowball, G., & Rowlands, J. (2019, June 11). Domestic homicide reviews (DHRs) and men: Emerging learning [Conference presentation], Respect 2019 Taking Male Victims of Domestic Abuse Seriously Conference, London, UK.

Trevillion, K., Hughes, B., Feder, G., Borschmann, R., Oram, S., & Howard, L. M. (2014). Disclosure of domestic violence in mental health settings: a qualitative meta-synthesis. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 430–444. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.924095

Walby, S. (2004). The cost of domestic violence. Women and equality unit. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/21681/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

Walklate, S., Fitz-Gibbon, K., McCulloch, J., & Maher, J. (2020). Towards a global femicide index: counting the costs. Routledge.

Websdale, N. (2020). Domestic violence Fatality Review: the state of the art. In R. Geffner, J. W. White, L. K. Hamberger, A. Rosenbaum, V. Vaughan-Eden, & V. I. Vieth (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal violence and abuse across the Lifespan. Springer International Publishing.

Woodhouse, T. (2021, April 13). Highlighting the relationship between domestic abuse and suicide Progress and next steps [Online presentation], AAFDA Seminar: Reviewing Domestic Abuse Related Suicides and Unexplained Deaths, Swindon, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. However, James Rowlands and Sarah Dangar are both practitioners and work in the Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) field. Their professional affiliations are described in the manuscript. With thanks to the study participants for their contribution, to Tanya Palmer for her comments on an early draft, and to the anonymous reviewers for their feedback. This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number: ES/P00072X/1).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowlands, J., Dangar, S. The Challenges and Opportunities of Reviewing Domestic Abuse-Related Deaths by Suicide in England and Wales. J Fam Viol 39, 723–737 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00492-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00492-z