Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an important gender-based, social, and public health problem that affects women worldwide, including women who are pregnant or have recently given birth. Studies have shown that violence against women often increases during pregnancy and the postpartum period. This study aims to examine lifetime and past-year prevalence of IPV among postpartum women in Malaysia, and to determine the socio-demographic as well as husband’s/partner’s behavioral factors associated with IPV exposure. This is a nationwide, cross-sectional and clinic-based study involving a total of 5727 women at 6 to 16 weeks postpartum, who attended randomly selected government health clinics between July to November 2016. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained female enumerators based on a pre-validated structured questionnaire, using mobile devices as data collection tools. Chi-squared tests and multivariable logistic regressions were used to investigate selected factors associated with IPV exposure. The lifetime and past-year prevalence of any form of IPV among postpartum women were 4.94% (95% CI [3.81,6.39]) and 2.42% (95% CI [1.74,3.35]) respectively, with the highest prevalence being emotional violence, followed by physical and sexual violence. Multivariable analysis showed that husband’s/partner’s behaviors, such as frequent alcohol use, drug use, fighting habits and controlling behaviour were significantly associated with both lifetime and past-year IPV (all p < 0.001 for past-year IPV). These findings suggest that prevention and intervention strategies for IPV should consider the prevention of substance use and reducing controlling behaviors by husband/partner, as well as raising awareness to build healthy relationships through education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as “any behavior within an intimate relationship or ex-relationship that causes physical, emotional (psychological) or sexual harm, including acts of physical aggression, psychological abuse, sexual coercion and controlling behaviors” (World Health Organization 2012). IPV is a major social and public health problem that affects women worldwide, including women who are pregnant or have recently given birth. The World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheet on violence against women reported that about one in three (35%) women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual IPV or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime (World Health Organization 2016). In low and middle-income countries of the Western Pacific Region, nearly a quarter (24.6%) of women reported experiencing violence by their intimate partners (World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and South African Medical Research Council 2013). With regard to IPV during pregnancy, the prevalence ranged between 1% in Japan to 28% in Peru, while the majority of the other low- and middle-income countries surveyed showed a range between 4% and 12% (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2005).

In Malaysia, a national survey conducted by the Women’s Aid Organization (WAO) in 1990 reported that 39% of women older than age 15 years suffered some form of violence and, furthermore, 68% of battered women were beaten while pregnant (Abdullah et al. 1995). A prevalence study done by Shuib et al. (2013) found that 8% of women in Peninsular Malaysia had experienced IPV in their lifetime, inferring that more than eight hundred thousand women in Malaysia who have likely experienced abuse. There has been an increasing trend in reported cases of violence in Malaysia such - from 3173 cases in 2010 to 4807 cases in 2014, 5014 cases in 2015, and 5796 cases in 2016 (Women’s Aid Organization, 2017). A small scale study involving 710 female adult patients who attended primary health care clinics in Selangor, a state in Malaysia, revealed that 5.6% of the patients screened positive for domestic violence using the validated Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) (Yut-Lin and Othman 2008). More information about IPV such as causes and consequences of IPV against women, as well as barriers in management of IPV at primary care level, are limited and missing in the context of Malaysia. Hence, more research on the aforementioned aspects of IPV is needed in Malaysia in order to understand the factors associated with IPV, to enable policy makers plan for integrated programs as well as to further strengthen existing programs and services at primary care level for early detection, management and prevention of IPV.

Although violence affects women of all ages, studies have shown that violence often increases during pregnancy and the postpartum period (Martin et al. 2012; Stewart et al. 2013). In this regard, several variables have been found to be risk factors, including socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., unmarried, with lower levels of education, or lower incomes), history of violent victimization and characteristics of violence perpetrators (current or former intimate partners) (Martin et al. 2012). In particular, persons who perpetuate violence against pregnant or postpartum women are found to be very likely to have problems with substance use, such as alcohol and illicit drugs (Nasir and Hyder 2003; Tzilos et al. 2010). Research has also shown that women who experienced IPV during pregnancy and the postpartum period are at higher risk for postpartum mental health problems, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and that these problems could influence women’s reactions to their babies (Kendall-Tackett 2007). Moreover, women who are victims of IPV are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors themselves, such as having multiple sex partners, and alcohol and drug abuse (CDC 2017). In view of the potential magnitude and diversity of the health problems and the fact that violence against women is preventable, appropriate measures should be taken to address the issue in a multisectoral and comprehensive way.

Despite the existence of a Violence and Injury Prevention Unit at the Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia since 2004, IPV and violence against women generally have been viewed as issues of lower priority compared to other key health issues within MOH (Colombini et al. 2012). In-depth interviews with policy makers revealed that the low priority and scarce attention given to IPV and MOH action at regional level are due to the lack of national prevalence data on violence against women (Colombini et al. 2012). Hence, it is important to obtain national data on prevalence of IPV and its associated factors in order to support development of policies and effective strategies against IPV in Malaysia. In this regard, the government health care setting is viewed as ideal for screening and implementing strategies to address IPV because of its wide coverage throughout the country. Considering the higher risk of IPV among women during pregnancy and the postpartum period, this study aims to determine the prevalence and factors associated with lifetime and past-year IPV among postpartum women attending government primary health care clinics in Malaysia. This study describes socio-demographic factors and husband’s/partner’s behaviors that are related to IPV experience in a national sample of postpartum women. This is the first nationwide study to explore the relationships of husband’s/partner’s substance use, violence and controlling behaviors with IPV among postpartum women in Malaysia. We believe this study will provide baseline evidence towards developing appropriate interventions for prevention and management of IPV in Malaysia.

Methods

Study Sample

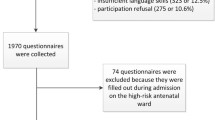

This cross-sectional study was targeted to women at 6 to 16 weeks postpartum who attended the selected government primary health care clinics between July and November, 2016. A two-stage cluster sampling design was employed in the selection of respondents. All 16 states within Malaysia were included in the sampling. Government health clinics within each state were selected from the sampling frame of all government primary care clinics (total 934 clinics) using systematic probability proportional to size sampling techniques. In total, 106 clinics were selected throughout Malaysia as the primary sampling units, and eligible postpartum women within the selected clinics were randomly selected as the secondary sampling units. Eligible respondents included postpartum women (6 to 16 weeks after childbirth) who were at least 18 years of age at time of the survey, gave informed consent to participate in this study, able to understand Bahasa Malaysia or English, and did not suffer from psychosis. Women who were very sick and could not be interviewed and those who did not give consent were excluded in this study. The sample size was calculated using a single proportion formula for the estimation of prevalence. Based on 8% as the estimated prevalence of IPV in Malaysia (Shuib et al. 2013), using an error bound of 5%, design effect of 2, and considering an anticipated non-response or drop-out rate of 20%, the final sample size needed was 6584 women. We ended up sampling a total of 6669 respondents in this study.

Survey Procedure

We used the bilingual (Bahasa Malaysia and English) WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Life Events Questionnaire (World Health Organization 2000) which has been locally validated for use in Malaysia (Saddki et al. 2013). The respondents were interviewed by trained female nurses (enumerators) face-to-face on a one-to-one basis in private without the presence of their husband/partner at the selected government health clinics. Prior to conducting the survey, the enumerators were trained to conduct interviews specifically related to physical and sexual abuse. The questionnaire was installed on mobile devices and all answers from the respondents were digitally recorded. The survey procedure was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-15-2404-26677). Informed consent was sought and obtained from all the study participants and confidentiality was assured.

Measures

Outcome Variables

The outcome variables in this study were “lifetime IPV” and “past-year IPV”. “Lifetime IPV” was defined as women’s lifetime exposure to any of the three types of IPV – physical, emotional, and sexual violence by a current or former husband/partner. “Past-year IPV” was defined as women’s exposure to physical, emotional and/or sexual violence by a current or former husband/partner in the past 12 months. “Experienced physical violence” was defined if a woman reported having ever experienced any act of violence from her current or former husband/partner, such as being slapped; had something thrown at her that could hurt; being pushed, grabbed, or had her hair pulled; being hit with a fist or something else that could hurt; being kicked, dragged or beaten up; being choked or burnt; or being threatened with or had a weapon (e.g., gun or knife) used against her. “Experienced emotional (psychological) violence” was defined if a woman’s current or former husband/partner had ever in her lifetime insulted her or made her feel bad about herself; degraded or humiliated her in front of others; threatened or made her scared (e.g., by the way he looks at her, shouts or breaks things); threatened to hurt her or somebody whom she cares about. “Experienced sexual violence” was defined if a woman reported having ever experienced any act of sexual violence from her current or former husband/partner, such as being physically forced to have sexual intercourse; had unwanted sexual intercourse because of fear of what her partner might do; or being forced to do something sexual that she found degrading or humiliating. All these questions related to violence had binary responses of “yes” or “no”. Women’s lifetime and past-year exposure to any of the three types of violence by a current or former intimate partner were used as the outcome variables in logistic regression analysis.

Independent Variables

There were 13 independent variables in this study: 9 variables on socio-demographic characteristics and 4 variables on husband’s/partner’s behavioral factors. Socio-demographic variables included: i) age of respondents, grouped as 18–24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 years; ii) age of current husband/partner, grouped as 15–24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 years; iii) ethnicity of respondents, categorized as Malay, Chinese, Indian, ‘Other Bumiputeras’ (indigenous groups, local Sabahans and Sarawakians) and ‘Others’ (mostly foreigners, immigrants, both legal and illegal, residing in Malaysia); iv) marital status of respondents, categorized as currently married/has partner and not married/no current partner; v) educational status of respondents, categorized based on the Malaysian education system as no formal/primary education (those who had no formal schooling or those who had completed six years of primary school), secondary education (those who had completed six years of primary school and five years of secondary school that made up total 11 years of formal schooling) and tertiary education (those with diploma or higher qualifications); vi) educational status of current husband/partner, categorized as primary education, secondary education and tertiary education; vii) working status of respondents, categorized as working and not working/housewife; viii) occupation of current husband/partner, categorized as professional, semi-skilled, unskilled/manual, army/police and others; and ix) household monthly income, grouped as less than RM1500, RM1501-RM3000, RM3001-RM5000, and RM5001 and more.

Husband’s/partner’s behavioral factors comprised of alcohol use, drug use, involvement in physical fights and controlling behaviors. Alcohol use by current husband/partner was categorized as never drinks alcohol, drinks occasionally (less than once a month) and frequently drinks (daily/weekly/monthly). For drug use by current husband/partner, women who reported that their current husband/partner used drugs daily, weekly, monthly or less than once a month were coded as “yes”, while those who never used drugs were coded as “no”. Husband’s/partner’s involvement in physical fights was categorized as “yes” or “no” to the following question: “Since you have known your current husband/partner, has your current husband/partner been involved in physical fights with another person?” Controlling behavior was assessed by five questions asking the women whether their current (or last) husband/partner: a) did not permit them to meet their friends; b) tried to limit their contact with family; c) insisted on knowing where they were; d) were jealous if they talked with other men and e) accused them of unfaithfulness. All these questions had a binary outcome coded as “yes” and “no”. Women who responded “yes” to one or more of the controlling behavior questions mentioned above were classified as having experienced controlling behavior from their current (or last) husband/partner.

Statistical Analysis

A total of 5727 out of 6669 randomly selected women were successfully interviewed, giving a response rate of 85.9%. The frequency distributions of socio-demographic characteristics and husband’s/partner’s behaviors of the sample were analysed using descriptive statistics. The outcomes - experience of lifetime and past-year IPV - were analysed by socio-demographic profile and husband’s/partner’s behavioral factors. Chi-squared test was used to examine bivariate associations between the independent and outcome variables. Two separate multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to explore factors associated with lifetime and past-year IPV. All variables in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis because all those independent variables have been demonstrated to be potential confounders through research literature search (Ali et al. 2014; Capaldi et al. 2012; Sabri et al. 2014) and are important to be included in the final adjusted model regardless of whether they are statistically significantly related to the outcome. All independent variables were tested for multicollinearity and interactions with each other. Results of multivariable analysis are reported as crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Adjusted ORs are provided in addition to crude ORs because we are taking into account the effects of all other dependent variables included in the analysis. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were done using complex sample module in the IBM Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), taking into consideration the complexity of the sampling design. The “plan for analysis” in the complex sample module was created based on the survey, or final weight, which is the product of design weight and non-response weight.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive results in Table 1 shows that the majority of respondents were 25–34 years old (62.7%), of Malay ethnicity (67.9%), currently married/has partner (98.7%), and with secondary educational level (60.0%). The overall prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV among postpartum women in this study were 4.94% (95% CI [3.81,6.39]) and 2.42% (95% CI [1.74,3.35]) respectively. Respondents aged 18–24 years reported a higher prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV compared to those of older age. Respondents who were currently not married/no current partner, of secondary educational level, and with a monthly household income of less than RM1500 showed a significantly higher prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV compared to their respective counterparts. Both lifetime and past-year prevalence of IPV were also shown to be significantly higher among respondents whose current husband/partner frequently drink alcohol, ever used drugs, ever involved in physical fights and have controlling behaviors.

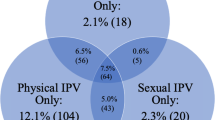

Table 2 shows the overall prevalence of any form of IPV (physical, emotional and/or sexual violence) experienced by women from their current or former partners in their lifetime and within the past 12 months, as well as lifetime and past-year prevalence of physical, emotional and sexual violence, individually. According to type of violence, emotional violence was the most prevalent type of violence, followed by physical and sexual violence.

Regression Results

Table 3 shows the results of both crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) identifying associations between each independent variable with lifetime and past-year IPV. Husband’s/partner’s behavioral factors significantly associated with a higher likelihood of lifetime IPV are frequent alcohol drinking (adjusted OR = 9.11, 95% CI [2.44, 34.04]), drug use (adjusted OR = 5.70, 95% CI [1.25, 26.07]), involvement in physical fights (adjusted OR = 23.48, 95% CI [8.65, 63.76]) and controlling behaviors (adjusted OR = 2.77, 95% CI [1.44, 5.33]). No significant association was observed with any of the socio-demographic factors in the adjusted model for lifetime IPV.

With regard to past-year IPV, Chinese women were significantly less likely to report experience of past-year IPV compared to Malay women (adjusted OR = 0.18, 95% CI [0.04,0.82]). Postpartum women who were currently not married/ no current partner were significantly more likely to have experienced IPV in the past year compared to those who were currently married/ has partner (adjusted OR = 11.27, 95% CI [2.26,56.17]). Other socio-demographic factors such as age, educational level and income level showed no significant associations with past-year IPV in the adjusted model. Similar to lifetime IPV, husband’s/partner’s behavioral factors were all significantly associated with a higher likelihood of women experiencing past-year IPV - frequent alcohol drinking (adjusted OR = 10.37, 95% CI [2.96, 36.33]), drug use (adjusted OR = 9.55, 95% CI [3.48, 26.18]), involvement in physical fights (adjusted OR = 10.81, 95% CI [3.60, 32.49]) and controlling behaviors (adjusted OR = 5.90, 95% CI [2.70, 12.86]).

Discussion

In this paper, we present baseline findings about experience of IPV among a national sample of postpartum women attending government primary health care clinics in Malaysia. Our study showed that 4.94% of Malaysian postpartum women reporting ever experiencing IPV in their lifetime and 2.42% of postpartum women reporting IPV experience in the past 12 months. The lifetime prevalence reported in this study is lower compared to a previous lifetime IPV prevalence study in Peninsular Malaysia (8%) (Shuib et al. 2013). The lifetime IPV prevalence found is also lower than that reported in other neighbouring countries such as Singapore (9.2%) (Chan 2013) and Thailand (41.1%) (World Health Organization 2010). The prevalence of IPV against women varies widely across different countries and study populations. Both studies in Malaysia as well as the study in Thailand used the same questionnaire from the World Health Organization, while the Singapore study used a different survey instrument, the International Violence Against Women Survey (IVAWS) Questionnaire. Different questionnaires used may yield different results due to differences in the scope and what is interpreted as IPV. In addition, our study only targeted postpartum women who had just given birth and were mostly still with their husband/partner at the time of the study. With the presence of newborn babies, they may want to forget about any IPV they had experienced earlier, hence the low prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV in this study. Furthermore, the low prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV found in this study may also be related to the fact that the sample was relatively young.

Similar to previous findings by Shuib et al. (2013), our study found emotional violence to be the most common type of violence, followed by physical and sexual violence. Emotional or psychological violence is observed to be more prevalent than physical and sexual violence. The low prevalence for violence in general, and sexual violence in particular, may be due to under-reporting. Cultural factors, social norms and beliefs that support IPV against women, stigma and fear of reporting may be the possible reasons for the low prevalence detected in this study (World Health Organization 2009). Furthermore, traditional male-dominated cultures perpetuate aggressive behavior in men and encourage submissive behavior in women in order to avoid confrontation, blame and stigmatization. Perceptions about women’s inferiority and inequality also prevent those affected from speaking out and gaining support (Kalra and Bhurga 2013).

Previous studies have shown that socio-demographic factors, such as age, educational level, socio-economic status, and relationship/ marital status are associated with women’s experiences of IPV (Kapiga et al. 2017; Lacey et al. 2016; Sabri et al. 2014). However, the associations have not been consistent and there have been numerous factors influencing the risk of IPV. In our study, the final adjusted multivariable analysis model for factors associated with lifetime IPV showed that none of the socio-demographic variables is statistically significant. This finding contrasts with other studies which have reported IPV related to low educational status of women (Onigbogi et al. 2015) and the husbands/partners (Al Serkal et al. 2014; Laelago et al. 2014), and low socio-economic status of the family (Abeye et al. 2011). The current study did not find any significant relationships between educational level and income level with women’s experience of lifetime and past-year IPV. It is possible that the lifetime and past-year IPV experiences captured in this study were mainly related to husband’s/partner’s behaviors, such as alcohol drinking, drug use, involvement in physical fights and controlling behaviors, regardless of the socio-economic and demographic background of the women or their husband/partner (Wandera et al. 2015).

Of note, for IPV experience within the past 12 months, it was observed in the adjusted model that postpartum women who were currently unmarried/ no partner were more likely to report past-year IPV compared to those who were currently married/ has partner. We speculate that it is possible that the victims terminated their relationship with their previous husband/partner following the incidence of past-year IPV that they had experienced. However, we did not collect information to test this theory in our study. Among different ethnic groups, Chinese women were found to be less likely to report past-year IPV compared to Malay women. A majority of our respondents were Malays and the problem of abuse among Chinese victims may be more hidden due to Chinese cultural values in maintaining a good reputation of themselves and their family (Chan 2006).

The present study reveals that women who reported that their current husband/partner consumed alcohol frequently were more likely to experience lifetime and past-year IPV compared to those women whose husband/partner never consumed alcohol. This finding is consistent with other studies (Mair et al. 2013; Testa et al. 2012). Nevertheless, it should be noted that evidence of a statistical association does not prove causality. Furthermore, alcohol consumption has been shown to not lead to a violent episode, per se, but to act as a situational factor that exacerbates conflicts between couples (Castro et al. 2017). The use of alcohol and subsequent intoxication may impair the ability to negotiate conflicts effectively, impair communication and bring about aggressive behavior which may contribute to IPV (Foran and O’Leary 2008).

Previous studies have shown a positive association between husband’s/partner’s drug use and IPV perpetration (Moore et al. 2008, 2011). In agreement with those studies, our study observed that current husband’s/partner’s drug use was significantly associated with higher odds of lifetime and past-year IPV among women. Similar to alcohol abuse, drug abuse may play a facilitative role in IPV by precipitating or exacerbating violence. It may be brought about by disruption of thinking process, manifestations of power, control, and hostile personality (Bennett and Bland 2008). Our findings suggest that drugs and alcohol abuse should be taken into account when designing interventions for addressing IPV and family problems. The underlying factors associated with drug abuse and the subsequent changes in personality or character that increase the likelihood of IPV needs to be further investigated.

Current husband’s/partner’s involvement in physical fights was found to be associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing lifetime and past-year IPV among women. This finding was supported by previous studies which have shown that male aggression or men who used violence to resolve conflicts with others are more likely to perpetrate IPV compared to men who did not resort to violence (Kiss et al. 2015; Owoaje and OlaOlorun 2012). A study has also shown that men with aggressive behavior tend to extend their violent behaviors to their partners (Balogun et al. 2012).

In addition, our study found that women who experienced current (or last) husband’s/partner’s controlling behavior have greater odds of suffering lifetime and past-year IPV. Controlling behavior is a known risk factor as reported in a study in Nigeria, where it was shown to be a precursor for IPV (Antai 2011). Another study in Pakistan by Ali et al. (2014) reported a prevalence of past year physical and sexual violence of 68.0%, and of these women, 51.6% experienced controlling behavior from their partners. This also restricts their ability to make their own decisions and to find solutions for their predicament (Ali et al. 2014). It appears that controlling behavior is not only a precursor for IPV, but also an underlying factor that may worsen the issue. A recent study by Roy Chowdhury et al. (2018) found that it is not the autonomous power of women, but a cooperative decision-making environment in a marital relationship that reduces violence. This indicates that the couples should also be made aware and educated through individually or joint family counselling programs to avoid situations that may lead to IPV.

The issue of violence against women should continue to receive attention from all relevant stakeholders who have a role in its prevention and control. Several resolutions on the intensification of efforts to eliminate all forms of violence against women have been adopted by the United Nationsoutlining steps and standards in international law for the protection of women against violence (United Nations 2013). In 2014, the 67th World Health Assembly (WHA) adopted a resolution entitled “Strengthening the role of the health system in addressing violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children” (World Health Organization 2014). As a signatory to these documents, Malaysia is committed to ensuring that steps are taken to address this issue, which requires policies and programs to be implemented based on scientific evidence. However, there is still insufficient data to support evidence-based primary prevention, as well as, for monitoring and evaluating intervention programs. In line with the public health approach to prevent violence against women, the Ministry of Health Malaysia is now focusing on training health personnel so that they are empowered to assess, counsel, refer and also advise in cases of abuse. The training includes awareness of the issue, laws on abuse, screening and early detection, proper use of local resources, as well as options for intervention. Besides that, the Ministry of Health Malaysia has established “One Stop Crisis Centers” (OSCC) since 1993, which is a place for victims to seek treatment in a patient-centered setting with a multi-disciplinary team providing specialist care. To date, almost all government hospitals in Malaysia have established this service.

Prevention and early intervention will be the most effective strategies to reduce the incidence of IPV. Our findings have important implications for development of effective prevention strategies and policy formulation. There is a need to focus on empowering women and upgrading their socio-economic status. Efforts should also be made to reach out to men so as to discourage excessive alcohol intake and interpersonal violence, promoting healthy behaviors, and improving communication and understanding in relationships. It has been suggested that family history of violence may have a role in perpetration or victimization for IPV (Capaldi et al. 2012). Future research should look into the relationship between family history of violence and the risk of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. More studies are also needed to establish if factors such as education and awareness, socio-economic well-being, promotion of family values, moral standards, and religious education can have a positive effect in reducing IPV. Nevertheless, a general approach would be to develop social skills even before marriage, such as conflict resolution, communication, stress and time management. There may be a role for early education at schools and pre-marital courses. Public awareness can be done via campaigns including the use of social media. The effectiveness of such broad preventive strategies remains questionable in view of the multi-factorial causes of IPV.

A study done by Oon et al. (2016) explored the coping mechanisms of women experiencing IPV in Malaysia and suggested that women seek help both from individuals (parents, siblings, friends) and authorities (hospital/health centre, police department, court, religious leaders) as part of their coping mechanisms in facing this problem. It is important to provide a supportive environment to support their help-seeking initiatives. The Ministry of Health currently focuses on establishing and improving services at the hospital-based One Stop Crisis Centres (OSCC). Emphasis is also placed on sensitising and training of the health clinic staff. Health clinics have been instructed to establish a multiagency team to review cases and take preventive measures. Such a multidisciplinary team, including clinical, psychiatric and counseling services, relevant NGO’s, welfare and the police department, has been established at the hospital-based OSCC but currently not at all district-level health clinics. Respondents who have been victims of IPV will want the opportunity to speak in private and in a comfortable setting. They must be confident that they will receive appropriate help in accessing the service. Front line staff at clinics must have the necessary information on the type of help that can be given and options available for the victims. These include when and where to refer clients, sources of legal advice, rights of victims, contacts of counselors, relevant NGOs in the area, shelter homes and options for treatment and legal action. A patient-centered service will increase the chances of victims reporting incidence of IPV. Such a service should ensure confidentiality, and not judge or discriminate but understand and empathise.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first nationwide study to collect information on prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV among postpartum women attending government primary health care clinics in Malaysia. The use of a locally validated instrument of the WHO multi-country study on violence against women enables international comparisons across different populations and countries. Additionally, the response rate was high (85.9%) despite the sensitive nature of the issue. However, several limitations should also be noted in this study. The cross-sectional study design prevents the establishment of cause-effect relationships between IPV exposure and explanatory variables. Because the data are cross-sectional, we cannot determine when the IPV occurred vis a vis their responses on their husband’s/partner’s behaviors. A different interview setting may also affect how questions are asked and how respondents answer. The higher prevalence found in other studies were from household surveys, while our study was conducted in a clinic-based setting. In a clinic-based setting, there may be time constraints for both the enumerators and the respondents. From the respondent’s perspective, time constraints and reluctance to divulge details to health clinic staff whom they regularly see might affect their disclosure. The setting may play an important role in terms of the accuracy of the information obtained as it may affect the focus that can be given by the respondents who initially came for their scheduled postnatal visits. Only women were interviewed and the potential for biased responses on their husband’s/partner’s behavioral characteristics cannot be discounted. Additionally, these variables were not measured based on a validated scale. Moreover, there is possibility of under-reporting of the true extent of the problem due to sensitivity of the violence issue. Finally, there may be also a strong possibility of under-reporting of drug use because of its illegal nature, and of alcohol use among Malays, who are Muslims, because of religious proscription, more so since most respondents were Malays. Hence, the actual magnitude of the problem may be higher than reported.

Conclusion

Although our study found a low prevalence of lifetime and past-year IPV among postpartum women in Malaysia, this study provides important information that IPV could be related to husband’s/partner’s behaviors which should be addressed to reduce its incidence. Alcohol and drug abuse are behaviors that can be modified. Controlling behaviors may be reduced by improving communication and understanding in a relationship. The findings of this study suggest the need to include the husbands/partners in the IPV prevention strategies. The incidence of IPV among women in Malaysia is most likely to be underreported considering the sensitivity of this issue and the fear of being stigmatized. Education and promotion of awareness regarding IPV should be intensified so that women are more willing to express their problems since violence, particularly emotional violence, may not be very obvious. This is important so that measures can be taken early to avoid escalation of violence and complications. Further longitudinal research to better understand the wide range of factors related to IPV in women, its health consequences and health-seeking behavior is also needed.

References

Abdullah, R., Raj-Hashim, R., & Schmitt, G. (1995). Battered women in Malaysia: prevalence, problems and public attitudes. A summary report of Women’s Aid Organization Malaysia’s National Research on Domestic Violence. Petaling Jaya: Women’s Aid Organization (WAO).

Abeye, S. G., Afework, M. F., & Yalew, A. W. (2011). Intimate partner violence against women in western Ethiopia: Prevalence, patterns, and associated factors. BMC Public Health, 11, 913. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-913.

Al Serkal, F., Hussein, H., El Sawaf, E., Al Faisal, W., Hasan Mahdy, N., & Wasfy, A. (2014). Intimte partner violence against women in Dubai: Prevalence, associated factors and health consequences, 2012-2013. Middle East Journal of Psychiatry and Alzheimers, 5(3), 19–27.

Ali, T. S., Abbas, A., & Ather, F. (2014). Associations of controlling behavior, physical and sexual violence with health symptoms. Women’s Health Care, 3, 202. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0420.1000202.

Antai, D. (2011). Controlling behavior, power relations within intimate relationships and intimate partner physical and sexual violence against women in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 11, 511. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-511.

Balogun, M. O., Owoaje, E. T., & Fawole, O. I. (2012). Intimate partner violence in southwestern Nigeria: Are there rural-urban differences? Women & Health, 52(7), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2012.707171.

Bennett, L., & Bland, P. (2008). Substance Abuse and intimate partner violence. Harrisburg, PA: VAWnet. http://www.vawnet.org. Accessed 3 Dec 2017.

Capaldi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231–280. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231.

Castro, R. J., Cerellino, L. P., & Rivera, R. (2017). Risk factors of violence against women in Peru. Journal of Family Violence, 32(8), 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9929-0.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2017). Violence prevention – Intimate partner violence: Consequences. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/consequences.html. Accessed 15 Dec 2017.

Chan, K. L. (2006). The Chinese concept of face and violence against women. International Social Work, 49(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872806059402.

Chan, W. C. (2013). Violence against women in Singapore: Initial data from the international violence against women survey. In J. Liu, B. Hebenton, & S. Jou (Eds.), Handbook of Asian criminology. New York: Springer.

Colombini, M., Mayhew, S. H., Ali, S. H., Shuib, R., & Watts, C. (2012). An integrated health sector response to violence against women in Malaysia: Lessons for supporting scale up. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 548. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-548.

Foran, H. M., & O’Leary, K. D. (2008). Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1222–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001.

Garcia-Moreno, C., Jansen, H. A., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Kalra, G., & Bhurga, D. (2013). Sexual violence against women: Understanding cross-cultural intersections. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(3), 244–249. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.117139.

Kapiga, S., Harvey, S., Muhammad, A. K., Stockl, H., Mshana, G., Hashim, R., Hansen, C., Lees, S., & Watts, C. (2017). Prevalence of intimate partner violence and abuse and associated factors among women enrolled into a cluster randomized trial in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 17, 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4119-9.

Kendall-Tackett, K. A. (2007). Violence against women and the perinatal period, the impact of lifetime violence and abuse on pregnancy, postpartum. and breastfeeding. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 8(3), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838007304406.

Kiss, L., Schraiber, L. B., Hossain, M., Watts, C., & Zimmerman, C. (2015). The link between community-based violence and intimate partner violence: The effect of crime and male aggression on intimate partner violence against women. Prevention Science, 16(6), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0567-6.

Lacey, K. K., West, C. M., Matusko, N., & Jackson, J. S. (2016). Prevalence and factors associated with severe physical intimate partner violence among U.S. black women: A comparison of African American and Caribbean blacks. Violence Against Women, 22(6), 651–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215610014.

Laelago, T., Belachew, T., & Tamrat, M. (2014). Prevalence and associated factors of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among recently delivered women in public health facilities of Hossana town, Hadiya zone, southern Ethiopia. Open Acess Library Journal, 1, e997–e999. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1100997.

Mair, C., Cunradi, C. B., Gruenewald, P. J., Todd, M., & Remer, L. (2013). Drinking context-specific associations between intimate partner violence and frequency and volume of alcohol consumption. Addiction, 108(12), 2102–2111. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12322.

Martin, S. L., Arcara, J., & Pollock, M. D. (2012). Violence during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Harrisburg, PA: VAWnet: The national online resource center on violence against women, National Resource Center on domestic violence.

Moore, T. M., Stuart, G. L., Meehan, J. C., Rhatigan, D., Hellmuth, J. C., & Keen, S. M. (2008). Drug abuse and aggression between intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 247–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003.

Moore, B. C., Easton, C. J., & McMahon, T. J. (2011). Drug abuse and intimate partner violence: A comparative study of opioid-dependent fathers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01091.x.

Nasir, K., & Hyder, A. A. (2003). Violence against pregnant women in developing countries: Review of evidence. European Journal of Public Health, 13(2), 105–107.

Onigbogi, M. O., Odeyemi, K. A., & Onigbogi, O. O. (2015). Prevalence and factors associated with intimate partner violence among married women in an urban community in Lagos state, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 19(1), 91–100.

Oon, S. W., Shuib, R., Ali, S. H., Endut, N., Osman, I., Abdullah, S., & Abdul Ghani, P. (2016). Exploring the coping mechanism of women experiencing intimate partner violence in Malaysia. International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.18769/ijasos.79459.

Owoaje, E. T., & OlaOlorun, F. (2012). Women at risk of physical intimate partner violence: A cross-sectional analysis of a low-income community in southwest, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 16(1), 43–53.

Roy Chowdhury, S., Bohara, A. K., & Horn, B. P. (2018). Balance of power, domestic violence, and health injuries: Evidence from demographic and health survey of Nepal. World Development, 102, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.09.009.

Sabri, B., Renner, L. M., Stockman, J. K., Mittal, M., & Decker, M. R. (2014). Risk factors for severe intimate partner violence and violence-related injuries among women in India. Women & Health, 54, 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2014.896445.

Saddki, N., Sulaiman, Z., Ali, S. H., Tengku Hassan, T. N., Abdullah, S., Ab Rahman, A., Tengku Ismail, T. A., Abdul Jalil, R., & Baharudin, Z. (2013). Validity and reliability of the Malay version of WHO Women’s health and life experiences questionnaire. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(12), 2557–2580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513479029.

Shuib, R., Endut, N., Ali, S. H., Osman, I., Abdullah, S., Oon, S. W., Abdul Ghani, P., Prabakaran, G., Hussin, N. S., & Shahrudin, S. S. H. (2013). Domestic violence and women’s well-being in Malaysia: Issues and challenges conducting a national study using the WHO multi-country questionnaire on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences, 91, 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.445.

Stewart, D. E., MacMillan, H., & Wathen, N. (2013). Intimate partner violence. A Canadian psychiatric Association’s postion paper. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(6), 1–15.

Testa, M., Kubiak, A., Quigley, B. M., Houston, R. J., Derrick, J. L., Levitt, A., Homish, G. G., & Leonard, K. E. (2012). Husband and wife alcohol use as independent or interactive predictors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(2), 268–276.

Tzilos, G. K., Grekin, E. R., Beatty, J. R., Chase, S. K., & Ondersma, S. J. (2010). Commission versus receipt of violence during pregnancy: Associations with substance abuse variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(10), 1928–1940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509354507.

United Nations (2013). Intensification of efforts to eliminate all forms of Violence Against Women Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 20 December 2012. (A/RES/67/144). https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/67/144. Accessed 3 Dec 2017.

Wandera, S. O., Kwagala, B., Ndugga, P., & Kabagenyi, A. (2015). Partner’s controlling behaviors and intimate partner sexual violence among married women in Uganda. BMC Public Heath, 15, 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1564-1.

Women’s Aid Organization (WAO). (2017). Perspectives on domestic violence: A coordinated community response to a community issue. A 2017 Report by WAO. Petaling Jaya: WAO.

World Health Organization. (2000). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and life experiences questionnaire (version 9). Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2009). Changing cultural and social norms supportive of violent behaviour. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/norms.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec 2017.

World Health Organization. (2010). Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2012). Understanding and addressing Violence Against Women: intimate partner violence. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec 2017.

World Health Organization. (2014). Violence and injury prevention: 67 th World Health Assembly adopts resolution on addressing violence. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R15-en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 6 Dec 2017.

World Health Organization. (2016). Violence Against Women: intimate partner and sexual Violence Against Women Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/. Accessed 6 Dec 2017.

World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & South African Medical Research Council. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yut-Lin, W., & Othman, S. (2008). Early detection and prevention of domestic violence using the women abuse screening tool (WAST) in primary health care clinic in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 20(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539507311899.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this paper. We acknowledge the Asia-Pacific International Research and Education (ASPIRE) Network for their contributions to the study concept. Our thanks also go to the staffs of the government health care clinics, for their assistance in data collection; and the study participants, for their willingness to participate in this survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, Y.Y., Rosman, A., Ahmad, N.A. et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence among Postpartum Women Attending Government Primary Health Care Clinics in Malaysia. J Fam Viol 34, 81–92 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0014-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0014-0