Abstract

Therapists and the public are becoming increasingly aware that psychotherapy can have side effects. The prevalence varies depending on the patients, treatments, settings, assessment methods and the researched type of side effect. Objective of this study is to assess side effects of routine outpatient psychodynamic and cognitive behaviour therapy. In a cross-sectional study cognitive behaviour therapist (n = 73) and psychodynamic psychotherapists (n = 57) were asked in a semi-structured interview about unwanted events and side effects in reference to their most recent patients (N = 276) using a domain inspection method. Their reports were cross-checked by an expert assessor. Multiple random-intercept models were conducted to investigate the influence of various variables. Therapists reported in 170 patients (61.4%) a total of 468 unwanted events. There was at least one side effect in 33.2% of the cases. Most frequent side effects were “strains in family relations” and “deterioration of symptoms”. Illness severity has a significant influence on the amount of side effects reported. The data confirm that side effects of psychotherapy are frequent. The difference between side effects and unwanted events shows the importance of such a distinction. The reporting of side effects for one in three patients may indicate an under recognition of side effects or reporting of only relevant or disturbing side effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is generally acknowledged that psychotherapy can cause side effects (Haupt et al., 2018; Strauss et al., 2021). Respective prevalence rates vary between 5% to nearly up to 100% (Crawford et al., 2016; Linden et al., 2015) depending on the definition of side effects, patient and therapist characteristics, different therapy schools, setting, specific interventions and assessment methods.

The evaluation of side effects necessitates a distinction starting with the identification of “unwanted events” that coincide with the treatment (Linden, 2013; Wysowski & Swartz, 2005). Unwanted events are considered as such due to their negative impact, assessed either by the patient, therapist, or in accordance with professional criteria. These events encompass both symptoms of illness and the patient’s well-being, challenges in social interactions, or disruptions in occupational performance (Linden & Schermuly-Haupt, 2014; Linden & Westram, 2010). To determine causality, it is imperative to elucidate the context in which the unwanted event occurred and its subsequent development. Unwanted events that can be traced back to the treatment process are termed “adverse treatment reactions.” However, adverse treatment reactions can only be classified as side effects, when they are associated with appropriate treatment. It’s essential to underscore that the consequences of inappropriate treatment or instances of malpractice cannot be classified as side effects. In summary, side effects of psychotherapy pertain to unwanted events that arise from proper treatment, are often unavoidable, and, in certain cases, may be intentionally considered (Linden, 2013; Linden & Schermuly-Haupt, 2014).

This general definition of side effects must be translated into assessment methods. Most studies rely on self-reports (e.g., Ladwig et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2013). Patients may recognize negative outcomes but might struggle to link them to therapy, a crucial aspect in defining side effects. The explicit request to report negative events can sometimes lead to over-reporting, serving as a means to express dissatisfaction or criticism (Leitner et al., 2013). Therapists, are better at distinguishing adverse treatment reactions from unwanted events, but may still have a bias when assessing the negative effects of their work (e.g., Hatfield et al., 2010; Lambert, 2010). Differences in patient and therapist perspectives can be due to idiosyncrasies, with therapists generally reporting fewer side effects than patients (Ladwig et al., 2014; Schermuly-Haupt et al., 2018). Therefore, an impartial expert assessor can be an objective alternative for evaluating side effects.

The level of detail in listing side effects within assessment instruments varies. Some instruments focus on specific treatment-related issues, such as deterioration during exposure treatment (Eshuis et al., 2021; Scheeringa et al., 2011). Alternatively, there are more generalized lists that offer limited coverage and cannot encompass the entirety of potential side effects (e.g., Parker et al., 2013; Rozental et al., 2016). A systematic and still feasible way is a domain inspection method, which does not inquire about individual side effects, but explores problems across all areas that may be affected by side effects, such as symptoms, occupational participation, and others (Grüneberger et al., 2017; Schermuly- Haupt et al., 2018).

Different frequencies in side effect reports are due to patient characteristics. There is empirical evidence that occupational status (unemployed), partnership status (living alone), the diagnosis of a personality disorder, or a migrant background can increase the amount of reported side effects (e.g., Ladwig et al., 2014; Rheker et al., 2017), while patient gender or age seem to have no great impact (Grüneberger et al., 2017).

Similarly, the treatment setting can influence the occurrence of side effects, with inpatients, psychiatric patients and patients in group treatment generally reporting more side effects (Gerke et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2021; Linden et al., 2015; Rheker et al., 2017). There are contradictory results in regard to psychotherapy schools as some studies show no effects (e.g., Grüneberger et al., 2017; Lambert & Barley, 2001), while others report differences, with higher frequencies for psychodynamic treatments (Jensen et al., 2010; Leitner et al., 2013). A longer treatment duration was seen as predictor for a greater likelihood of side effects, potentially explaining some of the aforementioned results (Leitner et al., 2013). Finally, a poor therapeutic relationship can result in more negative effects (Pourová et al., 2022; Sharf et al., 2010).

Considering the intricate nature of side effects in psychotherapy, there exists a compelling need for more comprehensive research. The primary aim of this study therefore is to investigate the prevalence and spectrum of side effects as reported by outpatient psychotherapists within the framework of routine care. This was done with a domain inspection method and cross checked by an expert assessor.

Given that we collected information from multiple patient vignettes reported per therapists, our dataset exhibits a dependent data structure. To comprehensively assess the impact of various factors, including different psychotherapy schools, duration of treatment, therapeutic relationship, severity and course of illness, impairment, educational level of the patient, age, gender, and migration background, we conducted multiple random intercept models. These analytical models were applied to account for the interdependence among observations and to systematically evaluate the influence of different predictors on the amount of reported side effects. These findings are pivotal in advancing our understanding of the complex landscape of side effects in psychotherapy and, consequently, in enhancing the quality of mental health care delivery.

Method

Therapists and Patients

In Germany, almost everybody is covered by health insurance, which reimburses either psychodynamic or cognitive behaviour therapy for up to 120 treatment sessions.

Referring to official listings of the Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Berlin (Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians) that was publicly available on the internet, established non stationary psychological psychotherapists were contacted randomly by telephone and e-mail, with no special selection, except for trying to recruit an equal number of psychodynamic and cognitive behaviour therapists.

Therapists were remunerated for their participation according to official reimbursement systems.

Therapists were asked to refer anonymously to the two to three patients of working age, whom they had seen recently. A minimal treatment duration of ten sessions was required, as this was seen as being sufficient to ask for side effects (Anderson & Lambert, 2001; Harnett et al., 2010).

Instruments

Interview

Therapists were interviewed in their office by researchers, who were themselves psychotherapists. The interviewers discussed with the therapists the case vignettes following a semi-structured interview schedule, that facilitated a thorough exploration and clarification of the therapist’s intended meaning. There was no additional training needed. Twenty interviews were rated by a second interviewer. The average interrater reliability across all items of the interview was κ = 0.803 (95% CI, p < .0005).

General Information

The interview encompassed the age of the patient, gender, family status, clinical diagnoses (with the possibility of multiple diagnoses), duration of illness, number of therapy sessions, therapeutic course, and additional related factors.

Severity of Illness

Severity of illness was classified by the clinical global impression scale (Busner & Targum, 2007) as (1) “not noticeable”, (2) “normal, not at all ill”, (3) “borderline mentally ill”, (4) “mildly ill”, (5) “moderately ill”, (6) “markedly ill”, (7) “severely ill”, or (8) “among the most extremely ill patients”.

Therapeutic Relation

Cooperation and sympathy were rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much”.

Course of Illness

The course of illness was rated as “first episode”, “recurrent”, “chronic exacerbating” and “chronic persistent”.

Functioning and Participation

The level of functioning and participation limitations were assessed with the Mini-ICF APP, which is a rating for limitations of activities and participation in psychological disorders based upon the international classification of functioning, which asks for adherence to regulations, planning, flexibility, competency, decision making, proactivity, endurance, assertiveness, communication skills, group behaviour, dyadic relations, self-care and mobility, with a minimum of zero and a maximum of 65 points, with higher ratings reflecting more severe limitations (Linden et al., 2014).

Unwanted Events and Side Effects

Side effects were assessed with a checklist similar to the UE-ATR checklist (Linden, 2013), which asks for unwanted events or side effects in fifteen domains: (1) family, (2) social relationships, (3) work, (4) changes in the life situation, (5) deterioration of symptoms, (6) occurrence of new symptoms, (7) relationship between patient and therapist, (8) patient discomfort during therapy sessions, (9) dependence on the therapist, (10) non-cooperation of the patient, (11) treatment outcome, (12) prolongation of therapy, (13) misuse of the therapy by the patient or third parties for other purposes, e.g. social benefits, (14) stigmatization, (15) coping with the disorder. Therapists were first asked, whether there were unwanted events in regard to all dimensions and it was then discussed whether this was directly linked to the treatment or not. The decision, to call an unwanted event a side effect was done following the recommendation of the UE- ATR-checklist (Linden, 2013). There must be evidence for a relation between the event and factors like diagnostic procedures, the treatment focus, the theoretical concept, treatment procedures, the treatment process, sensitization processes, disinhibition processes, treatment effects, and therapeutic relationship. The decision was made by both therapists to the best of their clinical judgement. We argue that this method is a valid approach for addressing the intricacies involved in evaluating unwanted events, adverse treatment reactions and side effects.

Statistics

Due to the therapists’ average reporting of 2.11 vignettes, our dataset exhibits a nested data structure, where patients (Level 1) are nested within therapists (Level 2). In response to this hierarchical data organization, we employed various multilevel analyses.

Models were fit using full maximum likelihood using the lme4 (Bates et al., 2015) package in R 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023). Inferential tests for fixed effects were conducted using t-tests with Satterthwaite degrees of freedom (dof) approximations computed using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017).

Ethics

The study was supported by a research grant from the State Pension Insurance Berlin-Brandenburg. The project was approved by the ethical committee of the Charité University Medicine Berlin (EA4/027/18) and by the data privacy department of the State Pension Insurance Berlin-Brandenburg. The therapists gave written informed consent. There was no direct contact with patients or any interference with the treatment.

Results

Therapists and Patients

A total of 326 therapists were approached, of which 131 agreed to participate in the study. The average age of therapists was 53.98 years (range 32–74 years, SD = 10.97 years), 74% were female, they worked as psychotherapists on average for 16.81 years (range 1–45 years, SD = 10.70 years) and were specialized in cognitive behaviour therapy (55.7%) or in psychodynamic therapy (43.5%). One was trained in both.

Therapists reported about n = 276 cases, with an average of 2.11 case vignettes per therapist. The average age of patients was 41.77 years (SD = 11.31), 64.9% were female, 56% had a high school education, and 12.2% a migrant background.

Clinical diagnoses as reported by the therapists were in 59.9% affective disorders, in 28.2% anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, in 24.2% trauma- and stress-related disorders, in 15.5% personality disorders, and in 14.8% somatoform disorders. According to the judgement of therapists, patients suffered from first episodes of mental disorders in 22.6%, from recurrent disorders in 37.9%, from chronic-exacerbating disorders in 10.3%, and from chronic-persistent disorders in 29.2% of the cases.

Patients were on average in treatment for 43.9 sessions (SD = 43.8). Therapists rated 43% of their patients as very sympathetic, 48.7% as rather likeable, and 8.3% as rather not. The cooperation with the patient was seen as very good in 52.7% of the cases, as rather good in 44.4% and as rather not good in 2.9% of the cases. On average the patients scored 25.24 (SD = 9.03) points in the Mini-ICF APP, reflecting a middle level of impairment.

Therapists reported an average of unwanted events in 1.69 (SD = 2.01, range 0 to 11) domains per patient. For 170 (61.6%) of the 276 patients therapists reported at least one unwanted event. From all unwanted events, 37.2% were classified as side effects, with an average of 0.63 (SD = 1.13, range 0–6) side effects per patient. This resulted in 33.2% of cases with at least one side effect.

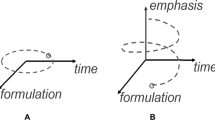

Most frequent unwanted events and side effects of all patients were “strains in family relations” (12.3% side effects, 15.5% unwanted events), “deterioration of symptoms” (11.2% side effects, 7.6% unwanted events) and “problems in coping with the disorder” (7.2% side effects, 9% unwanted events). This was followed by “prolongation of therapy” (6.1% side effects, 7.6% unwanted events), “patient discomfort during therapy sessions” (4.7% side effects, 1.1% unwanted events), “problems in the larger social network” (4% side effects, 15.2% unwanted events) and “dependence on the therapist” (3.6% side effects, 3.6% unwanted events), “emergence of new symptoms” (2.9% side effects, 3.6% unwanted events), “change in the life situation of the patient” (2.2% side effects, 10.8% unwanted events), “strains in work relations” (2.2% side effects, 9.7% unwanted events), “insufficient treatment outcome” (1.8% side effects, 10.5% unwanted events), “strains in the patient-therapist relationship” (1.4% side effects, 1.1% unwanted events), “others” (1.1% side effects, 4% unwanted events), “non-cooperation of the patient” (1.1% side effects, 3.6% unwanted events), “misuse of the therapy by the patient or third parties for other purposes” (0.7% side effects, 1.8% unwanted events), and “stigmatization because of the ongoing psychotherapy” (0.4% side effects; 1.4% unwanted events). The frequencies of reported side effects and unwanted events for psychodynamic and cognitive behaviour therapists are shown in Fig. 1.

Psychodynamic therapists reported unwanted events on average in 1.798 (SD = 2.07) of 15 domains per patient. Of these, 39.9% were declared as side effects, which averaged 0.72 (SD = 1.25) domains per patient. Cognitive behaviour therapists reported unwanted events on average in 1.6 (SD = 1.97) domains per patient, of which 34.7% were called side effects, accounting on average to 0.56 (SD = 1.03) domains with side effects per patient. At least one side effect was reported in 37.1% of the cases treated by psychodynamic therapists and in 30.1% treated by cognitive behaviour therapists.

Statistical models were constructed using the following model-building approach. At first, we conducted a null model to check if multilevel modeling is necessary. Afterwards we conducted multiple random intercept models using the different forementioned variables as Level 1 or Level 2 predictors and the sum of observed side effects as the outcome. The results can be seen in Table 1.

The results of our multilevel analysis show that illness severity, as measured by the clinical global impression scale, had a significant influence on reported side effects (β = 0.15, p = .007). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) varied between models (range 0.21 to 0.32) and showed the proportion of the total variance of the sum of reported side effects attributable to the therapist level.

Discussion

The potential for psychotherapy side effects is nearly limitless, and accordingly, the reported rates of side effects vary based on the assessment method, treatment setting, and patient or therapist characteristics. In a literature review, Herzog et al. (2019) examined different tools for measuring side effects and found little consensus. For instance, none of the instructions were identical concerning the coverage of side effects. The domain inspection method, as employed in this study, offers a comprehensive approach to detecting side effects. Within specific domains, such as “family,” clinicians can pinpoint and specify issues, such as sexual difficulties, partner conflicts, or the potential for divorce. Addressing these individual problems is crucial for effective treatment. However, when quantifying the impact of side effects, examining the entire domain can be a useful level of specification. The dual assessment of unwanted events and side effects by two therapists adds further validity to our findings.

In total there was at least one unwanted event in 61.4% of the cases and at least one side effect in 33.2% of the cases. The difference in the prevalence rates between treatment related side effects and treatment independent unwanted events shows the importance of such a distinction.

The observed rate of 33.2% falls within a similar range as the 43% rate reported by Schermuly-Haupt et al. (2018) in their study of 100 cognitive behavior therapists using a similar method. Boettcher et al. (2014) conducted an online survey with a reduced number of domains and found a lower prevalence of 14%. It’s worth noting that outpatients generally tend to report fewer side effects than inpatients (Gerke et al., 2020; Rheker et al., 2017).

Moreover, there is an increase in reported side effects when patients provide self-ratings, with rates such as 37.7% (Gerke et al., 2020), 50.9% (Rozental et al., 2019), 52.6% (Peth et al., 2018), 70.4% (Abeling et al., 2018), 71% (Pourová et al., 2022), 78.8% (Hoffmann et al., 2021), 84% (Grüneberger et al., 2017), 93.8% (Ladwig et al., 2014), or even 94% (Brakemeier et al., 2018) being reported. This discrepancy may arise because patients sometimes confound side effects with symptoms of their underlying condition.

In our study, we collected data based on what experienced therapists deemed significant enough to report, taking into account the unique characteristics of each case. Consequently, this enhances the clinical relevance of our findings. On the other hand, there may be the problem of under recognition of side effects, when relying on therapist instead of patient reports. Therapists are not exempt from the human tendency to overestimate positive events and are prone to judgement errors regarding the outcome of therapy as well as negative events (e.g., Chapman et al., 2012; Dunning et al., 2004; Lambert, 2010). Moreover, clinicians may have a tendency to attribute positive outcomes to their own efforts, while assigning negative ones to the patient (e.g., Małus et al., 2018; Westmacott & Hunsley, 2017). Therefore, our prevalence rates can be considered as the lower threshold in outpatient psychodynamic or cognitive behaviour therapy.

The absolute rate in all domains is above 1%, which would be considered as “common”, in the guideline on summary of product characteristics for pharmaceuticals by the European Commission (2009). Consequently, it is essential to provide patients with information regarding commonly occurring side effects prior to the commencement of their treatment and throughout (Jonsson et al., 2014).

Apart from the prevalence rates, our data also present how multi-facetted in regard to type and content side effects are. Most frequent were side effects in regard to “strains in family relations” (12,3%) and “deterioration of symptoms” (11.2%), followed by “problems in coping with the disease” (7.2%) and “prolongation of therapy” (6.1%). This is in line with other studies which also found interaction and family problems, dependency, worsening of symptoms, an increase of stress, or resurfacing of unpleasant memories as frequent (Rheker et al., 2017; Schermuly-Haupt et al., 2018; Strauss et al., 2021). An explanation may be that pivotal topics in psychotherapy are symptoms of illness and social interactions. Psychotherapy tries to elucidate the scope and ramification of the problems, as well as their origin and developmental context. This necessarily must reactivate problems, induce sensitization processes, cause stress, and even result in demoralization, as patients may get the impression that they are worse off than they thought before and that hope of recovery may vanish (Beevers & Miller, 2004; Lieberei & Linden, 2008). There can also be a negative impact on family members or partners as well as on work and colleagues (e.g., Lamprecht & Hessler, 1986; Löhr & Schmidtke, 2002). This can also impair the outcome of treatment and lead to a prolongation of the therapy (Hunsley, 1999; Kendall et al., 1992).

The literature on predictors or correlates of side effects is still inconsistent which may be due to the aforementioned problems with the different definitions, instruments and assessment methods (e.g. Herzog et al., 2019).

Contrary to other studies we could not find any evidence that a negative therapeutic relationship is a predictor for side effects (Abeling et al., 2018; Ladwig et al., 2014). Neither the rating of sympathy nor of cooperation demonstrated any significant impact on the reporting of side effects.

However, our study is in line with other research that show no effect of the therapy school on the amount of reported side effect (Ladwig et al., 2014; Lambert & Barley, 2001). These findings suggest that other more general factors, unrelated to the type of therapy employed, such as empathy, warmth, and emotional competencies or the lack of, may be more influential in accounting for the variations in side effect rates among therapists.

The multi-level analysis showed a significant impact of illness severity, demonstrating that therapists tend to report a higher number of side effects for patients exhibiting a more severe degree of illness. This finding aligns with prior studies that have reported elevated side effect rates among inpatients and psychiatric patients, substantiating the argument that heightened illness severity is linked to an increased amount of side effects (e.g., Gerke et al., 2020).

It is interesting that our analysis did not replicate many of the statements put forth by previous authors in other studies, as it revealed almost no significant predictors. Overall, the reasons for the lack of significant results may be divers and interpretations remain speculative, so further structured research is needed. For that it is important to come to an agreement on the definition of side effects as well as find an instrument that is recognized as the “gold standard” and is used in most of the studies to allow for a better comparability between studies.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study has several limitations as already discussed above. This is only a cross- sectional assessment. As a result, no distinction can be made between transient and persistent or between negative therapy effects of different therapy phases. An additional limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size. Even with 131 therapists and 276 patient vignettes, it may not be sufficient to reliably investigate side effects. Additionally, our design does not allow us to make any conclusions about the severity of the side effects. One condition for the selection of the cases was to choose the last patients with a minimum of 10 therapy sessions to avoid pre-selection by the therapists. The selection of the case solely dependent on the date of participation in the study, which provides protection against systematic biases. However, this criterion could not be conclusively verified and we had to rely on the therapists’ statements. Furthermore, it was not possible to control, if the treatment followed appropriate therapeutic rules and guidelines. Therefore, it cannot be conclusively determined whether unwanted events, side effects or mal- practice were reported. We only can say that the assessor, who in detail discussed the case with the therapist did not find indicators for malpractice. Similarly, we know what the therapist has been trained in, which may not be what was done in treatment. Our study is also limited to the therapist perspective and the difficulties associated with it.

Future research should combine the therapists’ and the patients’ perspective to allow for a holistic view on side effects and to further analyse the different reporting of side effects in the literature. A good example is the study by Muschalla et al. (2023). Furthermore, longitudinal studies with measurements during and after therapy are needed, with the purpose to highlight the course of negative therapy effects in different therapy phases and illustrate their relationship with therapy outcomes (i.e., remission, relapse, response, and dropout). Our method of asking for side effects per domain allows for a broad overview of problems in a patient’s life but is limited in regard to single side effects, which would need a combination with in-depth qualitative interviews. It should be standard to include negative effects and side effects alongside any research of therapy interventions (Jonsson et al., 2014). Future studies should include other variables such as patient motivation, coping strategies, or attachment behaviours as well as general psychotherapy factors. Another point of interest would be to research possible nocebo effects, that can occur when talking about side effects prior to the treatment. Finally, while our study provides valuable insights into the prevalence of side effects as perceived by therapists in routine care, it is important to recognize that RCTs offer a higher level of evidence when it comes to establishing causality, systematically assessing side effects, and controlling for confounding variables. Future research should consider incorporating RCTs alongside other research methods to provide a comprehensive understanding of side effects in psychotherapy, ultimately contributing to safer and more effective treatment practices.

In summary, the data confirm again that side effects are an important topic in psychotherapy (Dragioti et al., 2017; Jonsson et al., 2014). To respect patient rights, save patients from harm, and improve treatment outcome, therapists must be familiar with side effects, inform their patients, prevent negative developments, and take countermeasures when problems become apparent (Boswell et al., 2015; Crawford et al., 2016; Strauss & Linden, 2018). The UE-ATR Checklist (Linden, 2013) is a useful and feasible instrument in this regard.

Data Availability

The data of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abeling, B., Müller, A., Stephan, M., Pollmann, I., & de Zwaan, M. (2018). Negative Effekte Von Psychotherapie: Häufigkeit Und Korrelate in Einer Klinischen Stichprobe. PPmP- Psychotherapie· Psychosomatik· Medizinische Psychologie, 68(09/10), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-117604.

Anderson, E. M., & Lambert, M. J. (2001). A survival analysis of clinically significant change in outpatient psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(7), 875–888. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1056.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed- effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

Beevers, C. G., & Miller, I. W. (2004). Depression-related negative cognition: Mood-state and trait dependent properties. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000031804.86353.d1.

Boettcher, J., Rozental, A., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2014). Side effects in internet-based interventions for social anxiety disorder. Internet Interventions, 1(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2014.02.002.

Boswell, J. F., Kraus, D. R., Miller, S. D., & Lambert, M. J. (2015). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: Benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psycho- therapy Research, 25(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.817696.

Brakemeier, E. L., Herzog, P., Radtke, M., Schneibel, R., Breger, V., & Becker, M. (2018). … Nor- mann, C. CBASP als stationäres Behandlungskonzept der therapieresistenten chronischen Depression: Eine Pilotstudie zum Zusammenhang von Nebenwirkungen und Therapieerfolg. PPmP-Psychotherapie· Psychosomatik· Medizinische Psychologie, 68(09/10), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0629-7802.

Busner, J., & Targum, S. D. (2007). The clinical global impressions scale: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry, 4(7), 28–37. PMID: 20526405; PMCID: PMC2880930.

Chapman, C., Burlingame, G., Gleave, R., Rees, F., Beecher, M., & Porter, S. (2012). Clinical prediction in group psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 22(6), 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.702512.

R Core Team (2023). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Crawford, M. J., Thana, L., Farquharson, L., Palmer, L., Hancock, E., Bassett, P., Clarke, J., & Parry, G. D. (2016). Patient experience of negative effects of psychological treatment: Results of a national survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(3), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.162628.

Dragioti, E., Karathanos, V., Gerdle, B., & Evangelou, E. (2017). Does psychotherapy work? An umbrella review of meta- analyses of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiat- rica Scandinavica, 136(3), 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12713.

Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(3), 69–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x.

Eshuis, L. V., van Gelderen, M. J., van Zuiden, M., Nijdam, M. J., Vermetten, E., Olff, M., & Bakker, A. (2021). Efficacy of immersive PTSD treatments: A systematic review of virtual and augmented reality exposure therapy and a meta-analysis of virtual reality exposure therapy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 143, 516–527. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33248674.

European Commission (2009, September). A Guideline on summary of product characteristics (SmPC)https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/smpc_guide-line_rev2_en_0.pdf.

Gerke, L., Meyrose, A. K., Ladwig, I., Rief, W., & Nestoriuc, Y. (2020). Frequencies and predictors of negative effects in routine inpatient and outpatient psychotherapy: Two observational studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2144. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02144.

Grüneberger, A., Einsle, F., Hoyer, F., Strauss, B., Linden, M., & Härtling, S. (2017). Subjektiv Erlebte Nebenwirkungen Ambulanter Verhaltenstherapie: Zusammenhänge Mit Patientenmerkmalen, Therapeutenmerkmalen Und Der Therapiebeziehung. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 67, 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-104930.

Harnett, P., O´Donovan, A., & Lambert, M. J. (2010). The dose response relationship in psychotherapy: Implications for social policy. Clinical Psychology, 14(2), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2010.500309.

Hatfield, D., McCullough, L., Frantz, S. H., & Krieger, K. (2010). Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists’ ability to detect negative client change. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 17(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.656.

Haupt, M. L., Linden, M., & Strauss, B. (2018). Definition und Klassifikation Von Psychotherapie- Nebenwirkungen. In M. Linden, & B. Strauss (Eds.), Risiken Und Nebenwirkungen in Der Psychotherapie (pp. 1–13). Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

Herzog, P., Lauff, S., Rief, W., & Brakemeier, E. L. (2019). Assessing the unwanted: A systematic review of instruments used to assess negative effects of psychotherapy. Brain and Behavior, 9(12), e01447. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1447.

Hoffmann, D., Rask, C. U., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Jensen, J. S., & Frostholm, L. (2021). Efficacy of internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for severe health anxiety: Results from a randomized, controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 51(15), 2685–2695. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001312.

Hunsley, J., Aubry, T. D., Verstervelt, C. M., & Vito, D. (1999). Comparing therapist and client perspectives on reasons for psychotherapy termination. Psychotherapy: Theory, Re- search, Practice, Training, 36(4), 380. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087802.

Jensen, H. H., Mortensen, E. L., & Lotz, M. (2010). Effectiveness of short-term psychodynamic group therapy in a public outpatient psychotherapy unit. Nordic Journal of Psychia- try, 64(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039480903443874.

Jonsson, U., Alaie, I., Parling, T., & Arnberg, F. K. (2014). Reporting of harms in randomized controlled trials of psychological interventions for mental and behavioral disorders: A review of current practice. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 38(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.02.005.

Kendall, P. C., Kipnis, D., & Otto-Salaj, L. (1992). When clients don’t progress: Influences on and explanations for lack of therapeutic progress. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01183281.

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

Ladwig, I., Rief, W., & Nestoriuc, Y. (2014). Welche Risiken Und Nebenwirkungen hat psychotherapie? - Entwicklung eines Inventars Zur Erfassung negativer Effekte Von Psychotherapie (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie, 24, 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1159/000367928.

Lambert, M. J. (2010). Prevention of treatment failure: The use of measuring, monitoring, and feedback in clinical practice. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12141-000.

Lambert, M. J., & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory Research Practice Training, 38(4), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.357.

Lamprecht, F., & Hessler, M. (1986). Psychoanalytically oriented inpatient treatment: Its effect upon the untreated partner. Revista Chilena De Neuro-psiquiatría, 24(3), 143–147.

Leitner, A., Märtens, M., Koschier, A., Gerlich, K., Liegl, G., Hinterwallner, H., & Schnyder, U. (2013). Patients’ perceptions of risky developments during psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 43(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-012-9215-7.

Lieberei, B., & Linden, M. (2008). Adverse effects, side effects and medical malpractice in psychotherapy. Zeitschrift für Evidenz Fortbildung Und Qualität Im Gesundheitswesen, 102(9), 558–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2008.09.017.

Linden, M. (2013). How to define, find and classify side effects in psychotherapy: From Un- wanted events to adverse treatment reactions. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(4), 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1765.

Linden, M., & Schermuly-Haupt, M. L. (2014). Definition, assessment and rate of psychotherapy side effects. World Psychiatry, 13, 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20153.

Linden, M., & Westram, A. (2010). Prescribing a sedative antidepressant for patients at work or on sick leave under conditions of routine care. Pharmacopsychiatry, 43(01), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1231076.

Linden, M., Baron, S., Muschalla, B., & Molodynski, A. (2014). Mini-ICF-APP Social Functioning Scale. Hogrefe.

Linden, M., Walter, M., Fritz, K., & Muschalla, B. (2015). Unerwünschte Therapiewirkungen Bei Verhaltenstherapeutischer Gruppentherapie. Der Nervenarzt, 86(11), 1371–1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-015-4297-6.

Löhr, C., & Schmidtke, A. (2002). Führt Verhaltenstherapie zu Partnerschaftsproblemen? Eine Befragung Von erfahrenen und unerfahrenen Therapeuten. Verhaltenstherapie, 12(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1159/000064376.

Małus, A., Konarzewska, B., & Galińska-Skok, B. (2018). Patient’s failures and psychotherapist’s successes, or failure in psychotherapy in the eyes of a psychotherapist. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 3, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP%2F93739.

Muschalla, B., Müller, J., Grocholewski, A., & Linden, M. (2023). Effects of talking about side effects versus not talking about side effects on the therapeutic alliance: A controlled clinical trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(2), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13543.

Parker, G., Fletcher, K., Berk, M., & Paterson, A. (2013). Development of a measure quantifying adverse psychotherapeutic ingredients: The experiences of Therapy Questionnaire (ETQ). Psychiatry Research, 206(2–3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.026.

Peth, J., Jelinek, L., Nestoriuc, Y., & Moritz, S. (2018). Adverse effects of psychotherapy in depressed patients-first application of the positive and negative effects of psychotherapy scale (PANEPS). Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 68(9–10), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-101952.

Pourová, M., Řiháček, T., Chvála, L., Vybíral, Z., & Boehnke, J. R. (2022). Negative effects during multicomponent group-based treatment: A multisite study. Psychotherapy Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2095237.

Rheker, J., Beisel, S., Kräling, S., & Rief, W. (2017). Rate and predictors of negative effects of psychotherapy in psychiatric and psychosomatic inpatients. Psychiatry Research, 254, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.042.

Rozental, A., Kottorp, A., Boettcher, J., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2016). Negative effects of psychological treatments: An exploratory factor analysis of the negative effects Questionnaire for monitoring and reporting adverse and unwanted events. Plos One, 11(6), e0157503. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157503.

Rozental, A., Kottorp, A., Forsström, D., Månsson, K., Boettcher, J., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2019). The negative effects Questionnaire: Psychometric properties of an instrument for assessing negative effects in psychological treatments. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 47(5), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465819000018.

Scheeringa, M. S., Weems, C. F., Cohen, J. A., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Guthrie, D. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three- through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(8), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x.

Schermuly-Haupt, M. L., Linden, M., & Rush, A. J. (2018). Unwanted events and side effects in cognitive behavior therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-9904-y.

Sharf, J., Primavera, L. H., & Diener, M. J. (2010). Dropout and therapeutic alliance: a meta- analysis of adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: theory, research, practice, training, 47(4), 637. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021175.

Strauss, B., & Linden, M. (2018). Risiken Und Nebenwirkungen Von Psychotherapie. PPmP- Psychotherapie· Psychosomatik· Medizinische Psychologie, 68(09/10), 375–376. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0630-3297.

Strauss, B., Gawlytta, R., Schleu, A., & Frenzl, D. (2021). Negative effects of psychotherapy: Estimating the prevalence in a random national sample. BJPsych Open, 7(6). https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1025.

Westmacott, R., & Hunsley, J. (2017). Psychologists’ perspectives on therapy termination and the use of therapy engagement/retention strategies. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(3), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2037.

Wysowski, D. K., & Swartz, L. (2005). Adverse drug event surveillance and drug withdrawals in the United States, 1969–2002: The importance of reporting suspected reactions. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(12), 1363–1369. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.12.1363.

Funding

The study was supported by a research grant from the State Pension Insurance Berlin-Brandenburg.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The project was approved by the ethical committee of the Charité University Medicine Berlin (EA4/027/18) and by the data privacy department of the State Pension Insurance Berlin-Brandenburg.

Consent to Participate

The therapists gave written informed consent. There was no direct contact with patients or any interference with treatment.

Consent to Publish

The therapists gave written informed consent. There was no direct contact with patients or any interference with treatment.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balder, T., Linden, M. & Rose, M. Side Effects in Psychodynamic and Cognitive Behavior Therapy. J Contemp Psychother (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09615-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09615-5