Abstract

Case formulation is at the heart of personalised care in psychotherapy. Scientific research into case formulations can provide new insights in the heterogeneity of psychopathology which are relevant for advances in personalised psychopathology research and practice. This mixed-methods study examined the content of 483 fully personalised network-based case formulations in psychotherapy in terms of uniqueness (i.e., frequencies of concepts) and commonality (i.e., the presence of common themes over the different case formulations). In a real-world clinical care setting, patients co-created network-based case formulations with their therapist as part of their routine diagnostic process. These case formulations feature concepts that are relevant to individual patients and their current situation. We assessed how often concepts were used by different patients to quantify uniqueness. We applied a bottom-up thematic analysis to identify patient-relevant themes from the concepts. The case formulations of 483 patients diagnosed with mood and/or anxiety disorders contained a total of 4908 interpretable concepts of which 4272 (87%) were completely unique. Through thematic analysis, we identified seven overarching themes in the concepts: autonomy, connectedness, emotions, self-care, identity, self-efficacy, and bodily sensations. Case formulations were highly unique, thereby illustrating the importance of personalised diagnostics. The unique concepts could be grouped under seven overarching themes which seem to encompass basic human needs. Current advancements in personalised diagnostics and assessment should have a broader scope than symptoms alone, and could use the themes identified here as part of a topic list in the generation of (network-based) case formulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In response to the need for more personalised medicine and care, the heterogeneity of psychopathology has received renewed attention. For instance, studies found that individuals with the same diagnosis are likely to show very different symptom profiles (Fried & Nesse, 2015), illustrating the enormous heterogeneity within diagnostic categories. At the same time, however, these diagnostic categories often fail to capture all relevant symptoms of an individual, leaving many patients classified for multiple diagnoses at the same time (i.e., comorbidity; Borsboom et al., 2011; Kessler et al., 2005). Finally, psychopathology is dynamic rather than static, making patients ‘moving targets’ that can qualify for different diagnoses at different points in their life (Caspi et al., 2020). A personalised approach to psychopathology is needed to move beyond diagnostic categories and focus on specific individuals in specific contexts at specific points in their lives.

In research, the personalised approach to psychopathology is rapidly growing thanks to (mostly) methodological advancements such as the network approach and the use of time series analysis. In the network approach (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013), statistically estimated symptom networks (e.g. Bastiaansen et al., 2020), perceived causal problem networks (e.g., Klintwall et al., 2021) and formal network models (e.g. Burger et al., 2020) are used to study patient-specific symptom constellations. With time series analysis, repeated self-reports (e.g. daily questionnaire data) can be used to study the dynamics and interrelations of different processes in psychopathology and clinical change. While these novel approaches to personalised psychopathology research have already led to many interesting results, they could be better connected to psychotherapeutic practice. Specifically, personalised psychopathology research using networks and time series may benefit from engaging with the research and practice of idiographic case formulation (Kramer, 2020).

Case formulation is the key vehicle for personalising care in psychotherapy (Gazzillo et al., 2021; Krause & Behn, 2022; Kramer, 2020). In general, case formulation is understood as a combination of a description of the current situation of the patient, a hypothesis (or multiple hypotheses) about possible instantiating, maintaining, or alleviating processes, and possibly a plan of how to address these (Eells, 2015; Sim et al., 2005). Especially ‘bottom-up’ case formulation, focusing on idiographic characteristics of the patient, is argued to be the ‘royal road’ for personalised psychotherapy practice (Krause & Behn, 2022). Case formulation may also function as a bridge between psychotherapy practice and research, for instance by pointing out person-relevant processes to asses and monitor throughout a psychotherapeutic process (Kramer, 2020). However, research on case formulation is ‘still in its infancy’ (Kramer et al., 2022).

Until now, the recent methodological advancements in personalised psychopathology research have developed largely independent of case formulation research (for exceptions see Burger et al., 2020; Schiepek et al., 2016a, b) and an interesting discrepancy between the two research fields warrants further investigation. While almost all network and time series studies use the same variables for all patients, case formulation research points to person-specific variables as essential for personalisation (e.g., Kramer, 2020). In this paper, we aim to make a start in integrating these two bodies of literature by studying network-based case formulations including person-specific variables. By assessing the uniqueness of case formulations of different patients, we gain insight in the relative importance of personalised variables in personalised psychopathology research. Further, by qualitatively analyzing the concepts in the case formulations, we identify general important themes in case formulations which give additional insight in the processes that play a role in psychotherapy.

The case formulations studied here were constructed through idiographic system modelling (ISM; for an example of an ISM case formulation see Fig. 1). ISM is a bottom-up case formulation method developed by Schiepek and colleagues (Schiepek, 1986, 2003; Schiepek et al., 2016b). ISM is an integrative approach and not bounded to specific theories of psychotherapy or psychopathology. Instead, ISM has a meta-theoretical foundation in complex systems theory which assumes that all human processes are interdependent, cyclical and dynamic (Schiepek et al., 2016a, b; Olthof et al., 2023a). ISM shows some similarities to other case formulation methods that focus on connections between processes, such as plan analysis (Kramer et al., 2022), process-based therapy (Moskow et al., 2023) and functional analysis (Burger et al., 2020). However, following complex systems thinking, ISM has no hierarchical or sequential format but is explicitly cyclical with all components directly or indirectly influencing all other components.

Example of an idiographic system model in which concepts (e.g. “Anger”) are connected. Associations are either positive (+) or negative (−). For example, an increase in anger is associated with an increase in feelings of shame (+), whilst an increase in anger is associated with a decrease in ability to meditate (−)

The ISM method consists of the following steps that are revisited iteratively. First, the therapist conducts a semi-structured interview resulting in a topic list of concepts which are relevant for the patient’s current situation and for the desired outcome of the therapy process. This topic list is reviewed and adapted by patient and therapist. Second, the patient and therapist agree on a focus-concept from which to start the development of the network. The therapist then uses the following questions to connect the collected concepts: Which other concepts inhibit or foster the focus-concept? Which other concepts are inhibited or fostered by the focus-concept? The overall goal is to stepwise co-create a network, which visualizes the concepts most relevant to the patient in their circular co-dependency. For example, the focus concept may be ‘anxiety’. Then, other concepts that foster or inhibit ‘anxiety’ are added, with arrows indicating their influence. For example, ‘remembering trauma’ may increase anxiety (positive arrow), and ‘being with my family’ may decrease anxiety (negative arrow); see Fig. 1 for an example ISM). In addition to these in-coming arrows, the influence of anxiety on other concepts is added in the form of out-going arrows. In this example, the patient may feel less ‘confident’ or ‘more isolated’ when ‘anxiety’ increases.

For each concept that is added to the network, this very same process of searching for related concepts is repeated. The iterative process of adding, revisiting, and removing concepts and connections makes that the ISM gradually grows from a linear input-output scheme into a network of interconnections that entails direct and mediated feedback loops. Once there are no isolated concepts (“dead ends”) and patient and therapist feel that the network yields a satisfactory and “complete” case formulation, the process ends. Notably, ISMs can feature any idiographic concept which is a key difference to symptom networks (Kroeze et al., 2017) or perceived causal problem networks (Klintwall et al., 2021). The only restrictions are that concepts should be phrased in changeable terms (e.g. “feelings towards partner” is changeable but “partner” is not) and concepts that are related to desired states (e.g. “feeling happy”) and concepts that are related to undesired states such as symptoms are both explicitly included in the process.

The aim of the current study was to gain insight in the content of network-based case formulations. Many studies on case formulation in general, and network-based case formulation specifically (e.g., Schiepek et al., 2016a, b; Kroeze et al., 2017), focus on single cases, thereby providing deep insight in specific cases. While such studies are highly valuable, they are not suited for studying interindividual differences. As such, the extent to which network-based case formulations actually are personalised is yet unclear.

In the present study, we applied a mixed-methods approach to examine the concepts in ISM case formulations of 483 patients who received inpatient psychotherapy for mood and/or anxiety disorders. For the quantitative part, we examined the frequencies of the concepts in the ISMs to identify possible common concepts as well as on the uniqueness of the case formulations. For the qualitative part, we used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to examine the presence of general themes across the concepts of the case formulations.

Method

Participants

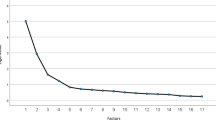

We analysed 586 ISMs generated by patients visiting a German private inpatient clinic for psychosomatic care between 2012 and 2019. ISMs from 103 patients were excluded due to technical errors (n = 49), e.g. absence of a (clear) photograph of the ISM, and inaccurately created models (n = 54), e.g. a lack of connections or concepts in the network. The final dataset consisted of 483 ISMs containing on average 15.30 concepts (SD = 4.73, range 5–36).

ISMs were analysed for 483 patients (58.8% female, age range 16–76, M = 46.43 years, SD = 12.71) who visited the clinic between 2012 and 2019. Patients received a primary diagnosis for recurrent major depressive (n = 199, 41%), single depressive (n = 183, 38%), phobic or other anxiety (n = 43, 9%) or other mood disorders (n = 57, 12%), based on the ICD-10. Of one patient, we could not retrieve the diagnosis. The clinic admits patients who have symptoms that are in Germany considered to be too severe for ambulant psychotherapy, but who are not in such a severe condition that they are admitted to a psychiatry ward. Patients are not admitted to the clinic in case of acute suicidality, drug dependencies or eating disorders. All patients in this sample had a Germany private health insurance with the extension “Gebührenordnung für Ärzte” or paid the treatment themselves. This type of insurance covers more health treatments than the general state insurance and is available without extra costs for certain government-employed professions such as teachers. It is also possible to purchase this insurance, in which case it is more expensive than the state insurance.

The clinic offers a standard treatment routine including group and individual sessions that incorporate therapeutic elements from different theoretical orientations, especially from systemic therapy and Ericksonian hypnosis (Schmidt, 2020), with ISM as an additional optional tool for case formulation. Data were collected as part of routine care which adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave consent to use their data for scientific purposes.

Therapists

There were 35 therapists involved conducting the ISM’s, of which 13 were trained as psychotherapists (in CBT, psychodynamic or systemic therapy), 7 body-therapists, 6 music-therapists, 3 physiotherapists and 1 person trained as art-therapist. In total, it took this pool of therapists 945 h to conduct the ISM’s (average per therapist: M = 27 h; Mdn = 9 h; SD = 43.41 h).

Materials and Procedure

All patients took part in a 1–3 h idiographic modelling session within the first two weeks following admission to the clinic. Modelling sessions were guided by therapists with varying therapy backgrounds. All therapists were trained in the method by an experienced in-house ISM training group. This group continuously supervised each other and trained newly arriving colleagues throughout the 8-year data collection period. ISMs examined in this study were created following the general process described in the introduction. For each patient, the handmade model was digitalized and the concepts were extracted. The concepts were translated to English, after which a native German speaker verified the translation. These concepts form the raw data of this study.

Data Analysis

For the quantitative part, the frequencies of the ISM concepts were calculated (i.e., how many individuals included a certain concept in their ISM). For the qualitative part, a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was applied to analyse the ISM concepts. Thematic analysis provides a “systematic approach for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns – themes – across a dataset” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 79). There are multiple forms of thematic analysis. We employed a bottom-up version of thematic analysis, meaning that we had no preconceived notions regarding the content of the themes, but rather identified the themes based on what was encountered in the data. Our epistemological position in the analysis is therefore constructionist. The thematic analysis approach involves six—recursive—phases of: familiarisation; coding; generating initial themes; reviewing and developing themes; refining, defining and naming themes; and writing up (Braun & Clarke, 2021). We implemented this approach as follows. The first author read and re-read all concepts to become familiar with the data. Through iterative and inductive coding, the data were categorized into non-overlapping themes and subthemes. For example, the variable “anxiety” was grouped under the subtheme negative emotions, and the variable “happiness” was grouped underneath the subtheme positive emotions. In turn, both subthemes would form different aspects of the main theme “emotions”. The wording, content, and structure of themes were iteratively discussed by all members of the research team to ensure that (sub)themes were internally consistent, i.e. concepts under the same theme were similar, and each theme captured a distinctive aspect of the data, i.e. concepts under different themes were dissimilar. The final thematic map was agreed upon by the research team. The MAXQDA software (VERBI Software, 2021) was used to organize the concepts into (sub)-themes.

Results

Data Inclusion

In total, the models contained 5468 concepts. The thematic map was based on 4908 (90%) of these concepts. The remainder of the concepts (560; 10% of total) were not included in further analysis because they could not be meaningfully interpreted.

Individual Differences in Concepts

Out of the 4908 included concepts, 4272 (87%) were completely patient-specific, meaning that they were mentioned by only one single patient, 481 (10%) concepts were mentioned more than once but less than five times, and 155 (3%) concepts were mentioned five times or more. The most common concept was “anxiety”, which was mentioned by 17.8% of all patients. Figure 2 contains a subset of the frequency distribution with only the 20 most often mentioned concepts.

Number of ISMs (frequency) in which each concept was mentioned at least once, displaying the top 20 most often mentioned concepts ordered by rank, with the percentage of all ISMs at the top of each bar. Note that certainty and safety are both related to the meaning of sicherheit in German and are therefore both retained in the English translation

Thematic Analysis

Seven main themes were constructed from the data (Fig. 3). Each theme is discussed below. Short examples, presented between quotation marks, are provided to illustrate its meaning. Subthemes are written in italics. A detailed, interactive figure of the thematic map including all underlying subthemes and concepts can be found at the open science framework [https://osf.io/afc7b/; DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AFC7B].

Autonomy

The theme autonomy is characterized by four subthemes. First, patients wanted freedom to act as they desired, being independent from others, and actively enjoying the freedom they achieved. Second, patients sought more sovereignty over their lives. They wanted “to be the captain on the ship” of their own life and to be able to stand up for themselves, e.g. “defend myself”, as well as restoring volition, e.g. “make autonomous decisions”. Third, patients included concepts related to control, either having a need for control, e.g. “want to control”, or letting go of control, e.g. “give up control”. Finally, patients sought to differentiate themselves from others, for example by defending their limits, e.g. “say stop”, or demarcating themselves, e.g. “can differentiate oneself well”.

Connectedness

The theme connectedness reflects the degree to which patients perceived themselves as part of a group. Three subthemes were identified. First, the experience of belongingness subtheme contained both a positive (feel like I belong) and a negative (do not feel like I belong) formulation. For the positive side, patients mentioned concepts related to giving or receiving support, e.g. “take care of others”, as well as feeling accepted by, in contact with and close to others. Patients sometimes did not feel like they belonged to the group, e.g. “being the outsider”, because they felt lonely or were actively rejected by others, e.g. “feel refused”. Second, the need to belong, reflecting the desire to be part of a group, was mentioned by patients. Patients had a strong desire for loving relationships in which they experienced affection and attachment, e.g. “seeking to be loved”. They wanted to be recognized, e.g. “feel seen”, and appreciated, e.g. “experience appreciation”, and mentioned pleasing others as a potential strategy to gain such appreciation, e.g. “please everyone”. Third, the subtheme relationships reflects both with whom the patient has relationships, e.g. family and friends, as well as the quality of those relationships, e.g. “secure relationship”. As another aspect of relationships, patients mentioned the skills employed to regulate their relationships such as “listen carefully” and “communication”.

Emotions

The theme emotions consists of two subthemes. Due to the similarity between emotions and feelings in everyday meaning, we grouped them together under emotions. Patients mentioned several experienced emotions, which were categorized as being positive or negative, and being high or low in arousal. Examples of high arousal positive emotions were joy, excitement, and happiness, whereas examples of low arousal positive emotions were satisfaction, ease, and lightness. High arousal negative emotions were characterized by anger, anxiety, fear, and pain, whereas the low arousal negative emotions focused on grief, guilt, emptiness, and sadness. Besides experienced emotions, patients mentioned their emotion regulation abilities. First, patients mentioned their ability to perceive their emotions, they wanted to gain “access to my own feelings”. However, it was also mentioned that this access was not always there, given that some patients experienced a lack of perception of their emotions. Second, whilst some patients stated that they suppressed their emotions, many sought acceptance, e.g. “allow feelings”. They wanted to “give space to emotions” and trust, e.g. “trust in my feelings”, and endure them, e.g. “enduring uncomfortable feelings”. Third, patients desired to share their emotions with others. This took the form of communicating them to others, e.g. “communicating emotions”, as well as expressing them directly by showing the experienced emotions, e.g. “show my fear to the outside”. Some patients in contrast stated that they covered their emotions and kept them inside, e.g. “not allowed to express pain”. Finally, various other emotion regulation strategies were mentioned by the patients such as down-regulating, withdrawing, ruminating, or reacting more cautiously to their emotions.

Self-Care

The theme self-care can be divided into five subthemes. First, patients had to deal with their needs in a constructive way. To do so, patients wanted to enhance the perception of their own needs, e.g. “see my needs”, as well as communicate them to others, e.g. “express my needs”, and finally take better care of these needs, e.g. “respond to my needs”. Second, patients mentioned bodily self-care, e.g. “to take care of my body”. By living a healthier lifestyle, e.g. “get healthy and fit” and exercising more often, e.g. “do more sports”, they wanted to enhance physical health. Furthermore, they wanted to trust, e.g. “trust in my body”, and accept their body more, e.g. “acceptance of your own body”, and listen to it, e.g. “pay attention to body feedback”. Third, patients included mental self-care. Growing a loving, e.g. “be loving with me”, accepting, e.g. “I am good the way I am”, and kind, e.g. “be nice to myself”, attitude towards their own self was relevant for many patients. Also, patients sought ways to better understand themselves, e.g. “understand me better”, feel in contact with themselves, e.g. “keep in touch with me” and feel protected and safe, e.g. “feel safe in me again”. The fourth subtheme of self-care was finding serenity. This means that patients sometimes wanted to “take time for myself”, seeking an accepting, e.g. “it may be as it is”, balanced, e.g. “find balance”, and peaceful, e.g. “in peace with me”, state of mind, allowing them to be “in the here and now”. Finally, patients mentioned self-negligence in that they undervalued, e.g. “nobody likes me”, neglected, e.g. “don’t pay attention to me”, or harmed themselves, e.g. “self-destruction”.

Identity

The theme identity contains five subthemes. Many patients mentioned their character traits such as perfectionism, courage, curiosity and openness. Additionally, patients included their perspective on life in their models, which consists of the direction of their focus, e.g. “focus on suffering”, the broadening of perspective, e.g. “step out of my usual frame of reference”, but also their general worldview, e.g. “realist” and experienced trust, e.g. “trust in life”. Besides this, patients also named the desire to know who they are by e.g. “find[ing] out who I am and what I like”, and developing themselves further by e.g. “find[ing] the right place to grow” or by “develop[ing] goals”. Finally, the identity of the patients contained the private and professional life of patients. The private life entailed hobbies such as “making music” and “painting”. The professional life consists of patients’ desire to make job related changes, e.g. “courage to change professionally” and to be satisfied with their job, e.g. “joy in work”.

Self-Efficacy

The theme self-efficacy reflects the believe patients have in their ability to reach desired goals and contains four subthemes. First, a fundamental part of experiencing self-efficacy formed the believe patients had in themselves. They wanted to regain their self-confidence, e.g. “I can do this”, and trust in themselves, e.g. “trust my skills”, feeling that “[I] can shape my life”. Second, patients mentioned the strength they have to move towards their desired goals, e.g. “I am strong”, whilst simultaneously being aware of the limits of their energy, e.g. “recharge battery”. Third, patients mentioned motivation and perseverance, such as having a performance orientation, e.g. “want to be the best”, as well as feeling pressured to fulfil expectations, e.g. “pressure to work”. Also, they mentioned their desire to come into action, e.g. “get going”, and persevere once they did so, e.g. “keep going”. Finally, patients mentioned their competence and both the absence, e.g. “helplessness”, and presence, e.g. “ability to convey” of it.

Bodily Sensations

The final theme is bodily sensations and contains descriptions of bodily states such as freezing, e.g. “be frozen”, and tension, e.g. “body tension”. Patients also mentioned bodily sensations located in specific parts of their body, such as headaches, tinnitus and heart symptoms. Finally, patients also mentioned concepts that influenced their physiological regulation, such as eating, e.g. “binge eating”, sleeping, e.g. “sleep disorder”, and substance use, e.g. “alcohol”.

Themes in Relation to ISMs

Last, we explored to which extent the codes that were grouped under the main themes were featured in the different ISMs. We found that codes grouped under autonomy were present in 65% of the ISMs, for the other themes this was: connectedness [81%], emotions [94%], self-care [97%], identity [86%], self-efficacy [81%] and bodily sensations [34%].

Discussion

This mixed-methods study examined concepts in ISM-based case formulations in a large sample of 483 patients that received inpatient psychotherapy. The quantitative analysis of the frequencies of the concepts showed a striking individuality in the case formulations. The case formulations were highly unique with the vast majority of concepts (87%) mentioned only by one single patient. The most common concept was “anxiety”, which was still only included in the ISMs of less than 20% of all patients. These results clearly demonstrate the importance of idiographic bottom-up case formulations, as they contain an immense richness which is not present in standardized diagnostics (e.g. DSM-5), top-down formulations, or case formulations derived from symptom networks (Robinaugh et al., 2020), or perceived causal problem networks (Frewen et al., 2012). Our quantitative finding demonstrates that the analysed ISMs reflect highly idiographic case formulations that capture the individuality of psychopathology.

In the thematic analysis, we identified seven themes that were important in the ISM case formulations: autonomy, connectedness, emotions, self-care, identity, self-efficacy, and bodily sensations. For every theme, the corresponding concepts were distributed over the majority of ISMs (except for bodily sensations). The themes correspond to important topics in transdiagnostic case formulations. For instance, the themes autonomy, connectedness and identity are in line with the proposal by Critchfield et al. (2022) that interpersonal relationship patterns are a crucial feature of case formulation. The other themes, emotions, self-care, self-efficacy and bodily sensations, are in line with Krause and Behn (2022) who emphasize the importance of emotion regulation and behavioural and cognitive factors besides interpersonal relationships.

We also note that the themes we found can be related to various basic psychological theories on basic human needs, such as the need for self-determination and autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 2000), the need to belong and maintain supportive relationships (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), as well as the need to regulate emotions (Gross, 1998). This also holds true for the need of self-compassion (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), the need to know what is important in life and your identity (Grotevant, 1987), the need to feel self-efficacious (Bandura, 1978) and the need for attachment (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). The presence of basic human needs in the case formulations may point to problems in need fulfilment and resources as general aspect of the case formulations (Eells, 2015).

Another theoretical model that is connectable to the themes is Klaus Grawe’s four dimensional model of human functioning (Grawe, 2007). Grawe names the need for attachment as a first fundamental human need, which maps closely to the theme of connectedness. Need for control can be related to the themes autonomy and identity, while the need for self-enhancement can be found in the themes and underlying concepts of self-efficacy and self-care. Grawe’s model also includes a meta-factor of coherence and congruence. Besides the content of the thematic map, the process of co-creating an ISM could in theory be related to this fifth basic need, by allowing a client to better understand herself and improve the capacity to reflect upon oneself (for empirical support see: Olthof et al., 2023b).

Mixed-Methods Interpretation

The different assumptions behind quantitative and qualitative analysis makes the integration of the current results, although extremely valuable, a delicate manner which necessitates further reflection and explanation. The quantitative result is based on counting and reveals an objective fact (the frequencies) about the concepts of the analysed ISM-based case formulations. The high individuality in the case formulations is thus observed, although the processes underlying the creation of the case formulations are highly complex and not analysed in this work. Certainly, the individuality we found is not only a characteristic of the patient sample but also of the ISM method and how therapists used it. The fact that the concept “anxiety” is only present in 17.8% of all formulations does thus not mean that anxiety is not relevant to other patients, but rather that many of them likely choose a more individualized expression of anxiety. Thus, although the quantitative analysis provides direct evidence for the individuality of the phrasing of the case formulations, it bears limited information about the content of the case formulations, precisely because the concepts used are so unique.

In the thematic analysis, the network nodes are treated as qualitative data that carry meaning in them that goes beyond the unique concepts, e.g. ‘anxiety’ and ‘anger’ are different concepts, yet are related in meaning as they are both emotions. As a structured and rigorous method, thematic analysis allowed to construct meaningful, higher-level themes from the very large set of idiographic concepts. It is this difference between observation in the frequency analysis and construction in the thematic analysis that must be appreciated in interpreting the results. What our results do show is that it is possible to construct higher-level meaning from the highly individualized observed concepts, leading to a richer understanding of the data and hence of the lived experience of patients and therapists. The identification of the themes, however, does not mean that the individualized concepts can be understood as specific manifestations of the themes. While the themes are constructed from the concepts, we cannot reduce the concepts to the themes as we do not make a causal claim about the relation between themes and concepts (like one does in the relation between observed and latent variables in factor analysis). Precisely this lack of reductionist or causal claim makes our mixed-methods results complementary: they provide related, but different, insights about the same data.

Strengths & Limitations

A strength of the current study is that it involves rich and ecological valid data. We analysed 483 case formulations that were created as part of routine care and not for research purposes. With this large sample, we could comprehensively study inter-individual differences in case formulations. In the form of ISMs, the case formulations could be studied as a structured and clearly interpretable data source. The ISMs allowed for both a quantitative analysis on the frequency of concepts, as well as a qualitative analysis on the meaning of these concepts. The complementary nature of this mixed-methods approach is another key strength of the present work.

Besides these strengths, the study also has its limitations. First, the present research dives into a certain type of case formulation (ISM) as has been constructed in a specific sample of patients by specific therapists at a specific clinic. While the ISM method has many advantages for studying the content of case formulations, such as its strong idiographic and participatory nature, it also has disadvantages as the non-hierarchical network does not allow for the depth that other case formulation methods like plan analysis (Grawe, 1980; Kramer et al., 2022) or plan formulation (Curtis et al., 1994) may have. The patient sample may be specific in terms of diagnoses and nationality, but also in terms of employment because they all had a specific private health insurance (which is standard in Germany for certain government-employed professions such as teachers) or paid themselves for the treatment. The ISMs may thus even have been more diverse if a broader sample of patients was included. Also, while ISM is aimed at purely idiographic modelling of the patient, it cannot be expected that the same patient would come to the same ISM with two different therapists (de Kwaadsteniet et al., 2010). The nesting of ISMs within therapists may thus have played a role in the current results, which cannot be taken into account in the present analysis. The specific therapeutic approach of the clinic has likely also been influential on the content of the case formulations, which could be studied by comparison with other clinics. Overall, our quantitative results cannot simply be generalized to other contexts. However, from these results, one can reasonably hypothesize that for idiographic case formulations, individual differences can be expected to be strikingly large. This assertion can be further examined in future research.

Generalization is not the aim of qualitative analysis, so the lack of generalizability is technically not a limitation, but we do wish to briefly discuss the issue. In bottom-up thematic analysis, as employed here, it is possible to arrive at multiple thematic structures that can be equally valid (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Besides the characteristics of the specific data as discussed above, the characteristics of the research team also influence the results, because construction of meaning is a subjective endeavour. This researcher subjectivity is not a limitation but a resource, as it is only through this subjectivity that we are able to construct meaning from the data at all (Clarke & Braun, 2018). The diversity of the research team in this study, in terms of nationality, gender, and, especially, professional occupation (therapists and researchers) may be seen as a strength in that regard. One should also note that subjectivity does not mean that ‘anything goes’. Thematic analysis has well-defined quality criteria (e.g. see Table 2 in Braun & Clarke, 2006)Footnote 1, which we rigorously applied in the current study. We do not claim generalizability of our qualitative results in the sense that the same themes will or should be identified in different studies on case formulations. However, given the universality of basic human needs such as taking care of oneself and feeling connected, we consider it highly plausible that the themes we identified have general relevance to a wide variety of patients and therapists in various contexts.

A second limitation is that we only had secondary access to the data, i.e. data were foremost collected for therapeutic and not scientific purposes. Due to ethical restrictions, we could not in retrospect ask the patients for an explanation or context of their case formulations. For the qualitative analysis, this means that our data were relatively ‘shallow’ in the sense that we could not include contextual information about the ISM creation process. Related, we could not meaningfully interpret some highly idiosyncratic concepts which were therefore not included in the final thematic map. Future research could study the ISMs with more contextual information by for instance also using audio or video recordings of the ISM creation and/or in-depth interviews with patients and therapists.

Implications

Our findings have several implications for psychopathology research and practice. First, our findings show that case formulations are highly individualized if the case formulation method allows. Creating such rich personalised case formulations demands a certain investment of time and resources in the beginning of therapy, but following Eells (2015), we argue that this is, at least in some cases, worthwhile. Personalised case formulations allow the therapist to fully adjust treatment to the patient and their situation leading to improved treatment planning, personalisation, and efficiency (Eells, 2022). Moreover, personalised case formulation, for instance with the ISM method (Schiepek et al., 2016a, b), helps patient and therapist to shape the beginning of their relationship and may increase feelings of connectedness (cf. Kramer et al., 2022). Also, getting to know the patient in depth early in treatment increases feelings of empathy in the therapist, which is beneficial for therapy outcomes (Eells, 2015). Overall, we recommend the use of personalised case formulations and point to ISM as one potentially useful method to guide such a formulation.

Second, the seven themes that we identified exemplify the wide and general scope of concepts in the case formulations, which are much broader than only symptoms, emotions and cognitions. More abstract, experiential, and existential themes are important as well such as identity, autonomy, and self-efficacy. Our findings thereby support recent calls to further move beyond a purely symptom-focused approach in clinical research and public health, and also incorporate the experiential dimension of psychopathology (de Haan, 2020; van Os et al., 2019). As a practical implication, our themes extent on previously proposed topics that can guide network-based case formulations (von Klipstein et al., 2020). Therapists may thus consider the themes we identified as part of a topic list for the creation of case formulations and potentially reduce own or clients’ blind spots.

Third, our findings point to possible roads to improvement in the field of personalised psychopathology research by integrating novel methodologies such as networks or time series with case formulation. Specifically, in order to fully capture person-relevant variables and processes, network- and time series studies should use idiographic concepts that extend beyond symptoms alone, but capture a wide variety of important themes in human life. With regard to networks, this would imply an extension beyond the generally used symptom- or problem-based approaches (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Frewen et al., 2012; Robinaugh et al., 2020; cf. Von Klipstein et al., 2020). With regard to time series, this would imply a move from standardized questionnaires with the same questions for every patient, to the use of personalised questionnaires (e.g., Lloyd et al., 2019; Weisz et al., 2011). In line with Kramer (2020), we would argue that these personalised questionnaires based on case formulation could then be used to study individual mechanisms of change in psychotherapy. Notably, the ISMs studied here were used to construct such personalised questionnaires to use for daily monitoring during psychotherapy (following the approach of Schiepek et al., 2016a, b) and we are indeed studying the resulting time series as well (Olthof et al., 2023b).

Conclusion

The present study shows striking individual differences in case formulations, in which almost 90% of the concepts were completely person-specific. Through thematic analysis we studied the content of all unique concepts and identified seven themes that describe the content: autonomy, connectedness, emotions, self-care, identity, self-efficacy, and bodily sensations. Combined, these results support a personalised approach to psychopathology that extends beyond symptoms and problems but also includes basic human needs.

Data Availability

The raw data are not made publicly available in order to protect the privacy of patients. The complete thematic map is available at the open science framework [https://osf.io/afc7b/; DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AFC7B].

Notes

An up-to-date resource on quality of thematic analysis can be found at https://www.thematicanalysis.net/quality-in-ta/.

References

Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1(4), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226.

Bastiaansen, J. A., Kunkels, Y. K., Blaauw, F. J., Boker, S. M., Ceulemans, E., Chen, M., & Bringmann, L. F. (2020). Time to get personal? The impact of researchers choices on the selection of treatment targets using the experience sampling methodology. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 137, 110211.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608.

Borsboom, D., Cramer, A. O. J., Schmittmann, V. D., Epskamp, S., & Waldorp, L. J. (2011). The small world of psychopathology. Plos One, 6(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027407.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

Burger, J., van der Veen, D. C., Robinaugh, D. J., Quax, R., Riese, H., Schoevers, R. A., & Epskamp, S. (2020). Bridging the gap between complexity science and clinical practice by formalizing idiographic theories: A computational model of functional analysis. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 1–18.

Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Ambler, A., Danese, A., Elliott, M. L., Hariri, A., Harrington, H. L., Hogan, S., Poulton, R., Ramrakha, S., Rasmussen, L. J. H., Reuben, A., Richmond-Rakerd, L., Sugden, K., Wertz, J., Williams, B. S., & Moffitt, T. E. (2020). Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Disorders and comorbidities across 4 decades among participants in the Dunedin Birth Cohort Study. JAMA Network Open, 3(4), e203221. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3221.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2018). Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 18(2), 107–110.

Critchfield, K. L., Gazzillo, F., & Kramer, U. (2022). Case formulation of interpersonal patterns and its impact on the therapeutic process: Introduction to the issue. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 379–385.

Curtis, J., Silberschatz, G., Sampson, H., & Weiss, J. (1994). The plan formulation method. Psychotherapy Research, 4, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503309412331334032.

de Haan, S. (2020). An enactive approach to psychiatry. Philosophy Psychiatry and Psychology, 27(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2020.0001.

de Kwaadsteniet, L., Hagmayer, Y., Krol, N. P., & Witteman, C. L. (2010). Causal client models in selecting effective interventions: A cognitive mapping study. Psychological Assessment, 22(3), 581.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

Eells, T. D. (2015). Psychotherapy case formulation. American Psychological Association.

Eells, T. D. (Ed.). (2022). Handbook of psychotherapy case formulation. Guilford Publications.

Frewen, P. A., Allen, S. L., Lanius, R. A., & Neufeld, R. W. J. (2012). Perceived causal relations: Novel Methodology for assessing client attributions about Causal associations between variables including symptoms and functional impairment. Assessment, 19(4), 480–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111418297.

Fried, E. I., & Nesse, R. M. (2015). Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR∗D study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172(February), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.010.

Gazzillo, F., Dimaggio, G., & Curtis, J. T. (2021). Case formulation and treatment planning: How to take care of relationship and symptoms together. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 31(2), 115.

Grawe, K. (1980). Die diagnostisch-therapeutische Funktion Der Gruppeninteraktion in Verhaltenstherapeutischen Gruppen [The diagnostic‐therapeutic function of group interaction in behavioral treatment groups]. In K. Grawe (Ed.), Verhaltenstherapie in Gruppen (pp. 88–223). Urban & Schwarzenberg.

Grawe, K. (2007). Neuropsychotherapy: How the neurosciences inform effective psychotherapy. Psychology Press.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

Grotevant, H. D. (1987). Toward a process model of identity formation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 2(3), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/074355488723003.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and Comorbidity of. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617.

Klintwall, L., Bellander, M., & Cervin, M. (2021). Perceived Causal Problem Networks: Reliability, Central Problems, and Clinical Utility for Depression. Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211039281.

Kramer, U. (2020). Individualizing psychotherapy research designs. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(3), 440.

Kramer, U., Fisher, S., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2022). How Plan Analysis can inform the construction of a therapeutic relationship. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 422–435.

Krause, M., & Behn, A. (2022). Case formulation as a bridge between theory, clinical practice, and research: A commentary. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 454–461.

Kroeze, R., van der Veen, D. C., Servaas, M. N., Bastiaansen, J. A., Voshaar, O., Borsboom, R. C., Ruhe, D., Schoevers, H. G., R. A., & Riese, H. (2017). Personalized feedback on Symptom dynamics of psychopathology: A proof-of-Principle Study. Journal for person-oriented Research, 3(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.17505/jpor.2017.01.

Lloyd, C. E. M., Duncan, C., & Cooper, M. (2019). Goal measures for psychotherapy: A systematic review of self-report, idiographic instruments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 26(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12281.

Moskow, D. M., Ong, C. W., Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2023). Process-based therapy: A personalized approach to treatment. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 14(1), 20438087231152848.

Olthof, M., Hasselman, F., Oude Maatman, F., Bosman, A. M. T., & Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A. (2023a). Complexity theory of psychopathology. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 132(3), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000740.

Olthof, M., Hasselman, F., Aas, B., Lamoth, D., Scholz, S., Daniels-Wredenhagen, N., Goldbeck, F., Weinans, E., Strunk, G., Schiepek, G., Bosman, A., & Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A. (2023b). The best of both worlds? General principles of psychopathology in personalized assessment. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 132(7), 808. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/jqp7g.

Robinaugh, D., Hoekstra, R., Toner, E., & Borsboom, D. (2020). The network approach to psychopathology: A review of the literature 2008–2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719003404.

Schiepek, G. (1986). Systemische Diagnostik in Der Klinischen Psychologie. Psychologie Verlags Union.

Schiepek, G. (2003). A dynamic systems approach to clinical case formulation. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.3.175.

Schiepek, G., Eckert, H., Aas, B., Wallot, S., & Wallot, A. (2016a). Integrative psychotherapy: A feedback-driven dynamic systems Approach. Hogrefe.

Schiepek, G., Stöger-Schmidinger, B., Aichhorn, W., Schöller, H., & Aas, B. (2016b). Systemic case formulation, individualized process monitoring, and state dynamics in a case of dissociative identity disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01545.

Schmidt, G. (2020). Einführung in die hypnosystemische therapie und Beratung. Carl-Auer Verlag.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

Sim, K., Gwee, K. P., & Bateman, A. (2005). Case Formulation in Psychotherapy: August, 3–6.

van Os, J., Guloksuz, S., Vijn, T. W., Hafkenscheid, A., & Delespaul, P. (2019). The evidence-based group-level symptom-reduction model as the organizing principle for mental health care: Time for change? World Psychiatry, 18(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20609.

VERBI Software. (2021). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. VERBI Software. Available from maxqda.com.

von Klipstein, L., Riese, H., van der Veen, D. C., Servaas, M. N., & Schoevers, R. A. (2020). Using person-specific networks in psychotherapy: Challenges, limitations, and how we could use them anyway. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01818-0.

Weisz, J. R., Chorpita, B. F., Frye, A., Ng, M. Y., Lau, N., Bearman, S. K., Ugueto, A. M., Langer, D. A., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2011). Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023307.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support provided by the Behavioural Science Institute. We thank Daniela Lamoth, Carlotta Albert and Ilse Roeleveld for assistance in data collection, Patricia Gill-Schultz for advice on the study design, Guenter Schiepek for training and helping to implement ISM at the sysTelios clinic, Mechthild Reinhard and Gunther Schmidt for founding sysTelios, and the entire sysTelios Health Center team for support during the collection of the data. We thank Jesper Meessen for the data visualisation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Behavioural Science Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: RB, MO, FG, KH, FP-B, SD, RO, BA, AL-A. Validation: all authors. Formal analysis: all authors. Data curation: FG, BA, ND-W. Writing – Original draft: RvdB, MO, AL-A. Writing – reviewing & editing: all authors. Resources: FG, KH, FP-B, ND-W, BA. Visualization: RvdB, MO. Supervision: ND-W, BA, RO, AL-A. Project administration: RvdB, MO, ND-W, BA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Data were collected as part of routine care which adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave consent to use their data for scientific purposes.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Bergh, R., Olthof, M., Goldbeck, F. et al. The Content of Personalised Network-Based Case Formulations. J Contemp Psychother (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09613-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09613-7