Abstract

Promotions are central to individual career success. For organisations, it is crucial to identify and develop employees capable of higher-level responsibility. Previous research has shown that personality traits as inter-individual differences predict promotions. However, effects have mostly been examined on a broad factor level. This study investigated longitudinal effects of Big Five personality traits on both factor (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and more detailed facet levels on promotions in employees of a multinational wholesale company (N = 1774, n = 343 promoted). We also explored how personality differentially impacts promotional likelihood as a matter of target job level (individual contributor vs. first- or senior-level manager roles). Overall, associations with promotions were detected for neuroticism (negative) and conscientiousness (positive). At the more nuanced facet level, all Big Five factors had at least one personality facet that was significantly related to promotions. Additionally, personality-promotion relationships were generally stronger for lower- rather than higher-level promotions. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that employee personality traits have a meaningful impact on who will be promoted and should hence be considered in organisational personnel selection, personnel development, and performance management practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Who gets promoted into expert roles or leadership positions? Promotions involve progression into hierarchically higher professional roles within the same organisation. Promotions are central to individual career success (Moutafi et al., 2007; Seibert & Kraimer, 2001), and organisations seek to identify and develop employees with the potential for higher levels of responsibility and leadership positions (Beechler & Woodward, 2009). Therefore, understanding which employee characteristics influence the likelihood of being promoted provides valuable practical insights for both employees and employers, facilitating better organisational performance management practices, personnel selection, and development (Gruman & Saks, 2011).

Inter-individual differences like personality traits predict a range of life outcomes (e.g. mortality, divorce, Roberts et al., 2007) including work-related outcomes such as promotions. Trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003) and person-organisation or person-vocation fit theories (Kristof, 1996) suggest that the fit between situational demands and individuals’ traits determines outcomes like job performance and differences in task effectiveness, interpersonal interaction, or performance motivation. Initial empirical studies suggested that employee personality explains a meaningful amount of variance in promotion outcomes. For example, in their meta-analysis, synthesising effects of personality using the Big Five model (with its five factors neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, Costa & McCrae, 1992), Ng and colleagues (2005) demonstrated that conscientiousness and extraversion positively predicted promotions, while neuroticism and agreeableness showed negative effects. For promotions into leadership positions, previous research suggested that extraversion plays a particularly important role (Ensari et al., 2011; Judge et al., 2002; Reichard et al., 2011). In two large samples (overall N = 12,765), Spark and colleagues (2022) showed that openness to experience, extraversion, and conscientiousness positively predicted promotion to leadership roles, while agreeableness and neuroticism were insignificant.

Although we have a basic understanding of employee personality-promotion relationships, this research is limited in at least three ways. Firstly, the number of studies on such associations is small. Ng and colleagues (2005) included only a few studies in their meta-analysis. Two more recent meta-analytic reviews on extraversion (Wilmot et al., 2019) and conscientiousness (Wilmot & Ones, 2019) encompassed the same or only a slightly higher number of studies. Secondly, only a few studies (Howard & Bray, 1990; Kassis et al., 2017; Moutafi et al., 2007) explored more detailed personality facets. Examining nuanced relationships offers a more a complete, albeit more complicated, insight into the role of personality traits (Judge et al., 2002). For example, the correspondence principle suggests that more specific measures of behavioural tendencies may better map on relevant actions in organisational contexts, which would positively predict a promotion (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). Thirdly, most existing evidence on personality-promotion associations comes from cross-sectional studies (Lee & Ohtake, 2012; Moutafi et al., 2007). It is hence difficult to make causal claims (Antonakis et al., 2010) due to unobserved third variables (Wilms et al., 2021) or reverse causality (e.g. promoted individuals become slightly more extraverted afterwards, Gensowski, 2018; Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007). Initial longitudinal studies showed that extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience positively predicted promotions or attainment of managerial levels several years later (Caspi et al., 1988; Howard & Bray, 1990; Judge et al., 1999; Nieß & Zacher, 2015). Still, we only have a limited understanding of the longitudinal effects of Big Five factors and facets on promotions to managerial or expert roles.

Firstly, our study contributes to the literature by investigating the effects of broader Big Five factors and more specific personality facets, offering more nuanced insights into the impact of personality traits on promotions than previous studies. It is practically and theoretically important to understand which Big Five facets predict promotions (Judge et al., 2002), defined here as moving up the company’s hierarchical structure by at least one hierarchical level (in line with Judge et al., 1995). Secondly, we look at differential associations between personality and promotions across different organisational job levels (i.e. promotions to expert roles versus leadership positions). Experts and leaders have different job profiles, and therefore different personality factors and facets should predict promotion (Mumford et al., 2007). Finally, we provide insights on the potential causal effects of personality on promotions by applying a longitudinal (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001) and counterfactual design (i.e. we tracked employees over time and assessed which personality traits predict promotions). Although we cannot fully rule out omitted variable bias (Wilms et al., 2021), the fairly stable nature of personality suggests that personality traits can be treated as exogenous (Antonakis et al., 2012; note that personality traits are not completely stable; for a review, see Bleidorn et al., 2022). In sum, our study offers insights into personality-promotion associations combining a longitudinal design, the investigation of personality facets besides broader factors, and the examination of differential personality effects on promotions by job level.

Individual Factors Related to Promotions

Research has related employee personality to career progression, for example via direct effects of personality on performance or because of selection effects (some employees being treated preferentially based on their personality characteristics, Roberts et al., 2007). Attitudes and behavioural tendencies should have meaningful effects on promotions (Ng et al., 2005), and studies showed that traits are associated with leader emergence (Judge et al., 2002) and job success in higher-level, managerial roles (Wilmot & Ones, 2021). Most studies that have investigated the effects of personality traits on promotions have operationalised personality according to the Big Five model’s factors (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Mount & Barrick, 1995). Although such research is useful, it provides a blunt understanding of how specific behavioural tendencies relate to promotions. Considerably less is known about how narrow personality facets predict promotions. Thus, we first briefly describe findings pertaining to the Big Five factors and then discuss facet-level research that can provide greater clarification of personality-promotion associations.

Big Five Model Personality and Promotions

Several studies have examined how the Big Five personality traits relate to employee promotions. A meta-analysis on personality trait effects on promotions (Ng et al., 2005) found small effects for the majority of Big Five traits (conscientiousness, r = 0.06, overall N = 4428; neuroticism, r = -0.11, N = 4575; agreeableness, r = -0.05, N = 4428) and a small to moderate effect for extraversion (r = 0.18, N = 4428), though the number of studies was quite small within this meta-analysis (only four to five samples for all personality traits). A more recent meta-analysis on conscientiousness found a comparable mean effect (ρ = 0.07), including nine samples (Wilmot & Ones, 2019). These meta-analytic effects were corroborated by more recent cross-sectional findings. Moutafi and colleagues (2007) found positive associations of current managerial level with extraversion (r = 0.17) and conscientiousness (r = 0.20) as well as a negative association with neuroticism (r = -0.19, N = 900). Further, the occupational level was associated negatively with neuroticism (r = -0.30, N = 90, Hülsheger et al., 2006). Lee and Ohtake (2012) showed a positive effect of extraversion on being in a management position in Japanese men only (r = 0.17, but not women, N = 4852; no effects in a US American sample, N = 3653). In summary, these few extant findings suggest positive but mostly small effects of extraversion and conscientiousness and a negative effect of neuroticism, plus a potential negative effect of agreeableness, on promotions. However, these studies have focused on broad personality factors, possibly obscuring more nuanced facet-level effects.

Narrow Personality Facets and Promotions

Only a few studies have looked at personality effects on a more detailed facet level, seeking out a more complete understanding how behavioural tendencies, thoughts, and feelings are associated with employee promotions. Judge and colleagues (2002) suggested that personality characteristics narrower than the broad Big Five factors may better predict work-related outcomes (see also DeYoung et al., 2007). For example, facets of extraversion and conscientiousness show differential associations with leadership-related outcomes (Bass, 1990; Mount & Barrick, 1995). One study on promotions situated in a highly structured work environment (professional football club’s youth academy, Kassis et al., 2017) showed that individuals who were low on a facet of agreeableness (i.e. principle which is about code, loyalty, morality orientation, valuing traditions, and norms) were more likely to be promoted 1 year later (N = 80). Facets of conscientiousness (ambition, achievement) and extraversion (dominance) positively and a facet of agreeableness (nurturance) negatively predicted attained managerial level in another study (N = 266, Howard & Bray, 1990). Moutafi and colleagues (2007) found that facets of neuroticism (anxiety, depression, self-consciousness, and vulnerability) are negatively and facets of extraversion (gregariousness, assertiveness, and activity) and conscientiousness (competence, order, dutifulness, achievement-striving, and self-discipline) are positively correlated with attainment of a managerial position. Further studies showed the effects of personality facets on outcomes related to promotions (such as income, job performance, and leadership effectiveness, Danner et al., 2019; Hülsheger et al., 2006; Palaiou & Furnham, 2014; Wilmot et al., 2019).

Thus, while only a few studies investigated personality facet effects on promotions, some initial findings suggest a potential merit of going beyond broad personality factors. Looking closely at facet-level effects for the factors agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and neuroticism may be especially fruitful (Moutafi et al., 2007; Palaiou & Furnham, 2014; Wilmot et al., 2019).

Differential Effects by Job Level

Although research has documented general relationships between personality and promotions, we know little about whether personality differentially relates to promotions across different hierarchical levels of organisations (i.e. experts vs. leaders). Relationships between personality and promotions may diverge based on differences in job demands, in line with fundamental work analysis principles (Morgeson et al., 2009) and trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003). If jobs at various organisational levels require different employee traits to be effective, then personality will relate to promotions differentially based on the position or managerial level an employee is promoted to. This may be because different positions and levels are characterised by diverging degrees of responsibility, influence, and leadership duties (Mumford et al., 2007), leading to specific effects of personality traits on promotion likelihood. However, only a few studies on promotions have specifically focused on differences across managerial levels (Moutafi et al., 2007) or on roles without managerial responsibility (Kassis et al., 2017). A moderating role of career stage as a distant proxy measure for job level has been shown for personality traits predicting career success (N = 457, Melamed, 1996). Here, the correlation of extraversion with the managerial level was positive and stronger for employees at a late-career stage than those at an early career stage. A study on non-managers, managers, and business leaders (managers of managers) has shown mean differences in personality traits, in that neuroticism and agreeableness were lower, and extraversion and conscientiousness were higher with increasing leadership level, on average (N = 5425, Furnham & Crump, 2015). In a meta-analysis on leadership outcomes, leader emergence defined as employees ascending to a leadership role was differentiated from leader effectiveness defined as the performance being in a leadership role, which may subsequently predict moving up into higher-level leadership roles (Judge et al., 2002). For both outcomes, positive effects of extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness (k = 17–37 effects, ρ = 0.16–0.34) were found, and negative effects of neuroticism (k = 18–30, ρ = − 0.22– − 0.24). Additionally, agreeableness was related positively to leadership effectiveness only (k = 19, ρ = 0.21). On a facet level, it has been suggested that facets of extraversion like being outgoing, energetic, joyful, and assertive should be positively influential for career success especially for jobs with frequent interpersonal interaction (Judge et al., 2002). Hence, these facets may be particularly relevant for managerial roles, relative to individual contributors. Still, there are few studies addressing these differential effects by job level, leaving a gap in understanding personality effects on promotions, especially on a more detailed facet level.

In our study, we focus on personality associations with promotion across three organisational levels: individual contributors, first-level managers, and senior-level managers (for a similar tripartite classification including two managerial levels, see Furnham & Crump, 2015). Firstly, individual contributors are those employees with no formal leadership duties (i.e. no subordinates), but with professional requirements concerning cognitive, interpersonal, and business skills. The next two job groups are marked by managerial/leadership duties. These are roles with formal authority over others including a responsibility to monitor, support, develop, and empower their employees as well as recognise their contributions (Yukl et al., 2002). In line with Speer and colleagues (2020), we divide managerial positions into two categories with diverging job demands: first-level managers and senior-level managers. Compared to first-level managers (with full supervisory responsibilities), senior-level managers are expected to show greater levels of business and strategic skills (Mumford et al., 2007). Based on this threefold classification, the individual contributor and senior-level manager roles are most dissimilar (Speer et al., 2020) and should potentially display diverging patterns in terms of personality effects on promotions. In contrast, the two managerial roles are most comparable, and hence, more similar personality associations are expected. Consequently, to examine differential effects based on diverging demands and requirements, in this study, three different kinds of promotions are distinguished by initial and target job level: first, promotions within individual contributor roles; second, promotions from individual contributor roles to first-level manager roles; third, promotions from first- to senior-level manager roles (with the latter one corresponding to Judge et al.’s (2002) notion of leadership effectiveness, given that promotions to senior-level managerial roles should at least partly depend on a manager’s effectiveness in the initial role). Thus, within this study, we were able to investigate how personality differentially relates to promotions across different levels of the organisation.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

In this study, we focus on the extent to which personality traits as stable inter-individual differences longitudinally predict job promotions within a multinational company. Such personality effects on promotions are looked at differentially by job level, not only on a factor but also on a facet level. We are hence replicating and extending earlier research results (Kassis et al., 2017; Lee & Ohtake, 2012; Moutafi et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2005) to provide further insights into predictive influences of personality on career success (Almlund et al., 2011; Gensowski, 2018; Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007) across different job levels (see Table 1 for a list of hypotheses based on empirical findings referenced in the table).

Materials and Methods

Sample

This study is based on data from a multinational wholesale company headquartered in central Europe operating in more than 20 European and Asian countries. Employees (N = 1774) self-reported on their Big Five personality traits (see below) between 2017 and 2022 (one assessment per employee). Demographic data were only available for n = 1400 participants who were still employed at the time of data collection (766 males, age range 23–66 years, M = 40.6, SD = 8.3, Table S1 shows an overview by country), but not those who left the company at some point after having taken the questionnaire (n = 376). Completion of the personality questionnaire was initiated by the employee or their manager to stimulate the employee’s personal development, or within structured talent and performance management processes with a focus on higher-level positions (such as talent and leadership programmes). For the 1774 employees, we retrieved the promotion data from the company’s HR information system (promoted, n = 343; not promoted, n = 1431; as of July 7, 2022, data available on promotions from 2018 to 2022). Promotions were defined as moving up the company’s hierarchical structure by at least one hierarchical level (Judge et al., 1995).

To avoid selection bias (Antonakis et al., 2010) and to assess predictive validity, we only included participants when they completed the Big Five questionnaire before they were promoted (excluding all employees who self-reported on their Big Five traits after having been promoted, although personality is relatively stable, it can be affected by major life events and a promotion subjectively may be seen as a major life event by some employees, Haehner et al., 2022; date of promotion was defined as the starting date in the new, hierarchically higher position). To differentiate effects by job level, all employees in the sample were grouped into one of three categories based on data from the HR information system and the talent management system employee levels: individual contributor, first-level manager, or senior-level manager. Managers are all those employees with formal leadership responsibility for at least one other employee. Categorisation into first- versus senior-level manager roles was based on hierarchical level obtained from organisational data (exemplary roles are “team lead” and “store manager” for first-level, and “department head” and “senior vice president” for senior-level managers, with senior-level managers presumably having a larger leadership span as a sum of direct and indirect reports, while first-level managers may have at least as many direct reports in some cases). Based on this classification, three kinds of promotions were distinguished: promotions within individual contributor roles (n = 68), promotions from individual contributor role to first-level manager role (n = 125), and promotions from first-level to senior-level manager role (or within manager roles to higher-level manager roles, n = 109; promotions from individual contributor role to senior-level manager role and promotions within first-level managers roles were theoretically possible but did not occur in this sample). Forty-one promoted employees for whom a classification was not possible due to missing data were excluded. Table S2 provides an overview of the promoted and non-promoted employees within each group. For both promotions within individual contributor roles and from individual contributor roles to first-level manager roles, those in individual contributor roles not promoted (i.e. not promoted to higher-level contributor role or to a managerial role) were selected as the comparison group (n = 393). For promotions from a first- to a senior-level managerial role, there were 740 individuals in first- or senior-level manager roles who were not promoted serving as the comparison group.

Measures

Big Five personality traits (factors neuroticism, extraversion, openness for experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) were measured using the commercial Reflector Big Five Personality questionnaire (Schakel et al., 2012) with 144 items (per factor 5 facets with 6 items each apart from openness to experience with only 4 facets, see Table S3 for an overview of all 24 facets) using a 5-point Likert scale with the endpoints “–” (“disagree”) and “ + + ” (“agree”). Factor values are based on a factor score matrix derived from item and facet data (Schakel et al., 2012). Because item-level data were unavailable for the main analyses, the factors’ and facets’ internal consistencies could not be determined for this sample. Still, the Big Five questionnaire used in this study has been shown to measure reliably in a separate, large representative sample (N = 1121, Big Five factors’ internal consistencies Cronbach’s ɑ = 0.86–0.93; for facets, ɑ = 0.66–0.82, Schakel et al., 2012, Table 2).

Statistical Analyses

Because of the binary dependent variable (0 = not promoted, 1 = promoted) and continuous independent variables (personality traits assessed using a 5-point Likert scale), binary logistic regression models (function glm) were built in R version 4.1.3 (R Core Team, 2019). To examine individual personality factor effects holding constant the other factors (Judge et al., 1999), multivariate logistic regression models including all five personality factors as independent variables and promoted as the binary dependent variable were run. Additionally, to investigate the potential effects of personality traits in more detail, separate multivariate models were examined with all facets per factor (four facets for openness, five for the other factors) as predictor variables. For robustness checks, the following control variables potentially influencing the associations between independent and dependent variables were included (Breaugh, 2011; Gensowski, 2018; Ng et al., 2005; Schmidt & Hunter, 2004): gender (male = 1, female = 2), age, and geographic region (to account for possible socio-cultural influences on the effects studied, employees’ countries of employment were grouped into seven European and Asian regions according to the United Nations “geographic regions” geoscheme, United Nations, 2022, Table S1) as fixed effects. A fixed-effects regression model does not assume that observations are drawn from the same population. Instead, it accounts for differences amongst samples by including a dummy-coded variable (i.e. 0 or 1). The dummy variable identifies the population the observation originates from and “removes all between-sample sources of variability from the model” (Curran & Hussong, 2009, p. 94).

To account for the nested data structure (individuals nested in regions), we relied on clustered standard errors, using the R packages sandwich (Zeileis et al., 2020) and lmtest (Zeileis & Hothorn, 2002). Clustered standard errors relax the assumption about independent residuals (Antonakis et al., 2010). Regression models were run for the entire sample to examine the overall effects of personality on promotions and also separately for the three kinds of promotions.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for factor- and facet-level personality traits and bivariate correlations with promotions are shown in Table 2. Bivariate correlations between personality factors are depicted in Table S4.

Overall Effects of Personality on Promotions

The multivariate logistic regression model revealed a positive effect of conscientiousness (hypothesis 2, β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, z = − 1.98, p = 0.048; Table 3) and a negative effect of neuroticism (hypothesis 3, β = − 0.11, SE = 0.03, z = − 4.00, p < 0.001; all other ps > 0.123) on being promoted in the full sample (i.e. all promotions combined). Those promoted at some point later described themselves as less neurotic and more conscientious, on average, than those not promoted (hypotheses 1 for extraversion and 4 for agreeableness were not supported). Adding the control variables age, gender, and region, only the effect of conscientiousness remained significant (p = 0.024, all other ps > 0.056; Table 3).

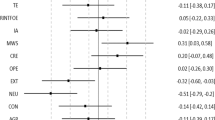

At the facet level (separate multivariate models per factor with all facets), significant positive effects on being promoted were found for imagination (factor openness, β = 0.10, SE = 0.04, z = 2.37, p = 0.018, Fig. 1), perfectionism (factor conscientiousness, β = 0.09, SE = 0.04, z = 2.04, p = 0.041), and drive (factor conscientiousness, β = 0.10, SE = 0.04, z = 2.49, p = 0.013), as well as significant negative effects of deference (factor agreeableness, β = − 0.07, SE = 0.03, z = − 2.26, p = 0.024) and trust of others (factor agreeableness, β = − 0.10, SE = 0.03, z = − 3.18, p = 0.001, for all other facets ps > 0.062; Fig. 1 and Table S5). Adding the control variables age, gender, and region, only the positive effect of drive remained significant (p = 0.028). Additionally, a positive effect of taking charge (factor extraversion, β = 0.09, SE = 0.04, z = 2.48, p = 0.013) and a negative effect of interpretation (factor neuroticism, β = − 0.09, SE = 0.03, z = − 3.30, p < 0.001, for all other facets ps > 0.128; Table S5) emerged. Thus, on a facet level in the full sample, those promoted described themselves as more imaginative, being perfectionists, and more driven, as well as seeking recognition and being more sceptical of others, on average.

Promotions into Higher-Level Individual Contributor Roles

The multivariate logistic regression model showed a negative effect of neuroticism (β = − 0.15, SE = 0.06, z = − 2.46, p = 0.014, other ps > 0.062; Table 3) on being promoted within individual contributor roles. Thus, those promoted at some point later described themselves as less neurotic, on average, than those not promoted. Controlling for age, gender, and region, the effect of neuroticism faded (p = 0.221) and a positive effect of agreeableness (β = 0.14, SE = 0.06, z = 2.35, p = 0.019, all other ps > 0.414; Table 3) was found.

At the facet level, significant positive effects on being promoted were found for sociability (factor extraversion, β = 0.20, SE = 0.09, z = 2.14, p = 0.032, Fig. 2), energy mode (factor extraversion, β = 0.18, SE = 0.09, z = 2.07, p = 0.039), taking charge (factor extraversion, β = 0.22, SE = 0.11, z = 2.13, p = 0.033), imagination (factor openness, β = 0.32, SE = 0.10, z = 3.19, p < 0.001, Fig. 2), and drive (factor conscientiousness, β = 0.24, SE = 0.09, z = 2.72, p < 0.001), as well as significant negative effects of reticence (factor neuroticism, β = − 0.22, SE = 0.09, z = − 2.37, p = 0.018), enthusiasm (factor extraversion, β = -0.21, SE = 0.08, z = − 2.62, p < 0.001), and agreement (factor agreeableness, β = − 0.15, SE = 0.07, z = − 2.06, p = 0.039; for all other facets ps > 0.10; Fig. 1 and Table S6).

Adding the control variables age, gender, and region, the positive effects of sociability (p < 0.001), taking charge (p = 0.0496), and imagination (p < 0.001) and the negative effects of reticence (p = 0.047) and enthusiasm (p < 0.001) remained significant, whereas the effects of energy mode (p = 0.262), agreement (p = 0.215), and drive (p = 0.074) faded. Additionally, a positive effect of directness was found (factor extraversion, β = 0.09, SE = 0.05, z = 2.06, p = 0.039; for all other facets ps > 0.074; Table S6). Thus, on a facet level, those promoted within individual contributor roles described themselves as more sociable, energetic, imaginative, and driven and more likely to take charge, as well as less enthusiastic, agreeable, and less likely to be reticent, on average.

Promotions from Individual Contributor to First-Level Manager Roles

The multivariate logistic regression model showed a negative effect of neuroticism (hypothesis 7, β = − 0.14, SE = 0.05, z = − 2.99, p = 0.003, other ps > 0.224; Table 3) on being promoted from an individual contributor to a first-level manager role. Those promoted later described themselves as less neurotic, on average, than those not promoted (finding no support for hypotheses 5, 6, and 8 on extraversion, openness, and agreeableness, respectively). Including the control variables age, gender, and region, the effect of neuroticism faded (p = 0.181, all other ps > 0.156; Table 3).

At the facet level, significant positive effects on being promoted were found for energy mode (factor extraversion, β = 0.20, SE = 0.06, z = 3.17, p = 0.002), imagination (factor openness, β = 0.20, SE = 0.07, z = 2.76, p = 0.006, Fig. 2), and drive (factor conscientiousness, β = 0.19, SE = 0.07, z = 2.84, p = 0.005), as well as significant negative effects of enthusiasm (factor extraversion, β = − 0.14, SE = 0.06, z = − 2.26, p = 0.024) and trust of others (factor agreeableness, β = − 0.11, SE = 0.05, z = − 2.05, p = 0.040, Fig. 2; for all other facets ps > 0.123; Fig. 1 and Table S7, no support for hypotheses 12, 13, and 14 on taking charge, directness, and reticence, respectively).

Adding the control variables age, gender, and region, only the positive effect of drive remained significant (p > 0.001), whereas the effects of enthusiasm (p = 0.806), energy mode (p = 0.072), imagination (p = 0.311), and trust of others (p = 0.508) faded. Additionally, a positive effect of change (factor openness, β = 0.08, SE = 0.03, z = 2.81, p = 0.005) and a negative effect of concentration (factor conscientiousness, β = − 0.13, SE = 0.05, z = 2.45, p = 0.014) were found (for all other facets ps > 0.162; Table S7). Hence, on a facet level, those promoted to first-level manager roles described themselves as more energetic, imaginative, and driven as well as less enthusiastic and trusting others, on average.

Promotions to Senior-Level Manager Roles

The multivariate logistic regression model revealed no significant effects on being promoted to senior-level manager roles (all ps > 0.071; Table 3). Controlling for age, gender, and region, a positive effect of conscientiousness (partial support for hypothesis 9, β = 0.15, SE = 0.07, z = 2.06, p = 0.040, all other ps > 0.302; Table 3) was found. Thus, those promoted at some point later described themselves as more conscientious (significant only when including the control variables).

At the facet level, a negative effect of interpretation (factor neuroticism, β = − 0.16, SE = 0.07, z = − 2.22, p = 0.027) was found (for all other facets ps > 0.087; Table S8). Adding the control variables age, gender, and region, the effect of interpretation remained significant (p = 0.015), and additional positive effects of drive (factor conscientiousness, β = 0.10, SE = 0.04, z = 2.46, p = 0.014) and methodicalness (factor conscientiousness, β = 0.19, SE = 0.07, z = 2.84, p = 0.005) emerged (all other ps > 0.054; Table S8), suggesting that managers who tend to use more optimistic explanations and to crave achievement and develop plans for everything were more likely to be promoted to senior-level manager roles (no support for hypothesis 11 on sociability).

Discussion

We investigated the longitudinal effects of Big Five personality traits on promotions, not only on a factor level but also on a more detailed facet level, across three different job levels (individual contributors, first-level managers, senior-level managers). Several major findings emerged.

Personality Effects by Big Five Factor

Those promoted were found to be more emotionally stable (i.e. less neurotic) and more conscientious, than those not promoted, supporting our hypotheses 2 and 3. Breaking this finding down by job level, employees promoted into higher-level individual contributor roles described themselves as more emotionally stable and more agreeable.Footnote 1 Employees promoted from individual contributors to first-level manager roles were also more emotionally stable. Employees promoted from first-level to senior-level manager roles described themselves as more conscientious.

These results were mainly in line with our hypotheses and earlier findings. The negative effects of neuroticism may be explicable by reduced job performance, suboptimal career management, and a reduced likelihood of career sponsorship (Ng et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2007). A specific mechanism of neuroticism’s negative association with promotion likelihood may be affective forecasting, which has been proposed for negative consequences of introversion in work settings (Spark et al., 2018, 2022). Similar to introverts, more neurotic individuals may be less likely to be promoted because they engage in behaviours contributing to being seen as a future leader based on their expectations that such behaviours may be unpleasant (Spark et al., 2018). Such a mechanism should be investigated specifically for neuroticism in future studies. Furthermore, more neurotic employees may be less likely to receive career sponsorship, due to their lower performance or being seen as more insecure, anxious, and hence less leader-like (Moutafi et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2005). More conscientious employees may be more hard-working, dutiful, motivated, ambitious, and self-efficacious, leading to increased performance and subsequently higher chances of being promoted (Brown et al., 2011; Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007; Moutafi et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2005). Also, it has been shown that conscientiousness positively influences work performance via heightened self-efficacy and setting performance goals (Brown et al., 2011). On the other hand, the null effects of conscientiousness with respect to promotions to first-level and senior-level manager roles and the small effect size overall are somewhat in line with a small meta-analytic effect size (Wilmot & Ones, 2019). This suggests that conscientiousness may not be universally supportive across job levels for promotions, contrary to earlier findings (Moutafi et al., 2007), and that instead, only some facets of conscientiousness may augment chances of being promoted (see below). On the other hand, the extraversion null effects are contrary to our hypothesis 1 and past research (Lee & Ohtake, 2012; Moutafi et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2005). Interestingly too, we found that agreeableness was positively related to promotions specifically for higher-level individual contributor roles. This was not hypothesised and contrasts earlier findings (Kassis et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2005). It appears that agreeableness may be useful for career progression in individual contributor roles, and especially in positions involving teamwork and close collaboration with colleagues or customers (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001), but consistent with past research, is largely irrelevant (at least on a factor level) when moving up into managerial roles (but see Blake et al., 2022 for a meta-analysis on the role of agreeableness in leader emergence).

Personality Effects on Facet Level

This study was unique in its focus specifically on nuanced personality facets. We found that promoted employees prefer coming up with new ideas (facet imagination, factor openness), have a continual need to refine or polish (perfectionism, conscientiousness), crave achievement (drive, conscientiousness), seek recognition (low deference, low agreeableness), and are more sceptical of others (low trust of others, low agreeableness) than those not promoted (Fig. 1 shows significant facet-level effects). Thus, by investigating results at the facet level, we revealed that personality facets linked to all Big Five factors were meaningfully related to promotions. However, results differed by job level.

When examining results by job level, employees promoted into higher-level individual contributor roles described themselves as more sociable, energetic, and direct; more likely to take charge; and less enthusiastic. This implies that those who prefer working with others, are active, enjoy the responsibility of leading others, and hold down positive feelings (and express their opinions directly) have better chances of being promoted to a higher-level individual contributor role. Also, regarding openness and conscientiousness, positive effects of imagination and drive were found, respectively, suggesting that those who create new plans and ideas and who crave achievement are more likely to be promoted. Concerning neuroticism and agreeableness, negative effects of reticence and agreement were found, respectively. This implies that those who enjoy being out front and welcome discussion have better chances of being promoted.

Employees promoted from individual contributor to first-level manager roles described themselves as more energetic and less enthusiastic (factor extraversion), implying that those who are active and hold down positive feelings have better chances of being promoted to first-level manager roles. Energetic behaviours may lead employees to be perceived as more leader-like, increasing chances of a later promotion (Spark et al., 2022). Regarding openness and conscientiousness, positive effects of imagination and drive were found, respectively. The relatively consistent positive effects of the facet imagination were not expected, given mostly inconsistent earlier findings regarding openness and career success (e.g. negative effect on income, positive effect on promotions, Nieß & Zacher, 2015; Seibert & Kraimer, 2001; for a discussion of the validity of openness and its facets in a work setting, see Mussel et al., 2011). Apparently, it is beneficial to be willing to create and pursue new concepts and ideas for achieving a promotion. This certainly deserves further attention in follow-up studies. Concerning agreeableness, a negative effect of trust of others was found, suggesting that those more sceptical of others are more likely to be promoted to a first-level manager role. Finally, employees promoted from first-level to senior-level manager roles described themselves as higher in drive and methodicalness (both factor conscientiousness), but lower in interpretation (neuroticism), implying that those who tend to crave more achievement, to develop plans, and to use more optimistic explanations have better chances of being promoted to a senior-level manager role. Regarding facets of conscientiousness, this underlines earlier findings and theorising that more conscientious employees are more motivated to perform and indeed show better performance (especially in occupations with low-to-medium versus high complexity), on average, and are also perceived as better-performing, increasing chances of receiving organisational sponsorship (Brown et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2005; Wilmot & Ones, 2019).

The facet-level results for promotions to higher-level individual contributor roles and first-level manager roles are mostly in line with the few available findings. For example, Moutafi and colleagues (2007) found similar associations with managerial level for neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness. Overall and for two of the three job levels, negative effects were shown for agreeableness facets (agreement, deference, and trust of others), similar to the study by Kassis and colleagues (2017, facet principle). Although these specific facets of agreeableness are somewhat diverse, this still suggests that being lower in facets of agreeableness may be supportive for promotions in different contexts (individual contributor and first-level, but not senior-level, manager roles, and highly structured work environments), for example by perceiving competition as problematic and less rewarding (Kassis et al., 2017). This implies that seeking harmony too strongly, being uncomfortable with praise, and trusting others too readily may be disadvantageous in competing for professional rewards and benefits (Kassis et al., 2017; Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). These opposing effects pave the way for future work for clarification.

While no effects for the factor extraversion emerged, for promotions to higher-level individual contributor and first-level managerial roles, positive associations were found for some facets (sociability, energy mode, taking charge, directness, similar to Wilmot et al., 2019 and as hypothesised for taking charge and directness for promotions to first-level manager roles (hypotheses 12 and 13), though contrary to hypothesis 10 of weaker extraversion factor and facet effects for promotions to higher-level individual contributor roles compared to the other job levels). These positive effects corroborate earlier suggestions that extraversion may exert positive influences through the attainment of status, social influence, and supportive mentorships (Holman & Hughes, 2021; Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007). However, at the same time, enthusiasm negatively predicted promotions. This suggests that those less expressive and better able to hold down positive feelings were more likely to be promoted. It could be argued that this facet ought to be part of agreeableness (Schakel al., 2012) in line with affiliation-themed variation (Woods & Hardy, 2012). Future work should attempt to replicate this finding and explore potential mechanisms (such as test-specific or company-specific cultural influences). Overall, setting aside enthusiasm, consistent effects of extraversion facets emerged—employees who described themselves as more sociable, energetic, taking charge, and direct were more likely to be promoted to higher-level individual contributor and first-level (but not senior-level manager) roles. This underlines the importance of going beyond broad personality factors and investigating personality effects on a detailed facet level (Hülsheger et al., 2006; Judge et al., 2002). Looking more closely at extraversion effects by job level, we found several positive effects of extraversion facets (e.g. sociability, energy mode, taking charge) for promotions to higher-level individual contributor roles and to first-level manager roles, but not for promotions to senior-level manager roles. This is somewhat contrary to the hypothesised pattern (hypothesis 10) that facets of extraversion supporting successful interpersonal interactions (e.g. being outgoing, energetic, joyful, and assertive) are especially implicated for higher-level, managerial promotions with more frequent social interactions. Thus, at least for managerial promotions in this sample, extraversion facets related to interpersonal interactions did not play a considerable role. It rather appeared that descriptively the influence of extraversion seems to fade for promotions to higher levels compared to lower levels (see effects of sociability depicted in Fig. 2). This pattern is somewhat contrasting earlier findings, such as on extraversion effects on both leadership emergence and effectiveness (Judge et al., 2002).

Some of the promotions considered in this data set have been decided in assessment settings like development centres or interviews. Positive effects on performance in these assessments have been shown for extraversion, conscientiousness, and emotional stability (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007; Spector et al., 2000), which may partly explain the patterns observed in this study. These factor- and facet-level effects and their mechanisms including moderators and mediators should be explored further for an even more complete understanding of personality effects on promotions in corporate contexts. Beyond the Big Five model (Costa & McCrae, 1992), future research may employ alternative conceptualisations of employees’ personality characteristics, such as the Great Eight model, which has been developed in the context of workplace performance (Bartram, 2005; Kurz, 2023a, b) to examine if this criterion-centric model would yield similar results concerning the prediction of promotions.

Implications for Theory and Research

These findings support theoretical reasoning that differences in job demands and responsibilities of individual contributor, first-level, and senior-level manager roles lead to diverging associations between personality and promotions. Such differential job demands, amongst other situational and contextual features, are embedded in trait activation theory (Judge & Zapata, 2015; Tett & Burnett, 2003) as moderating personality-performance relationships. Different hierarchical job levels may constitute contexts of diverging job demands, leading to diverging associations between employee personality and achieving a promotion. There may well be further contextual or organisational factors not accounted for in this study, which influence personality-promotion relationship (such as organisational policies, resources, or opportunities for development, Ng et al., 2005). Relatedly, person-organisation fit and person-vocation fit theories suggest that specific personality traits may show stronger associations with job performance in certain organisational settings or job types (Kristof, 1996; Ng et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2007). For example, Wilmot and Ones (2021) showed a moderating effect of occupational group (such as healthcare, law enforcement, or sales) on the relationship between personality and performance. Our study points towards similar patterns for associations between personality and promotion, implying that a differing fit between personality and job demands by job level may lead to diverging personality-promotion relationships. These ideas should be explored in future work to investigate in more detail which situational and contextual factors function as moderators of personality-promotion associations.

Another pattern in this study is that the higher the managerial level (individual contributors, first-level, and senior-level managers) on which promotions happen, the less influential is an employee’s personality (particularly on a facet level). Especially for senior-level manager roles, the question arises of which characteristics may instead more strongly predict promotions. Further skills and abilities beyond the Big Five personality traits, like cognitive abilities, emotional intelligence (Antonakis, 2004; Edelman & van Knippenberg, 2018; Rosete & Ciarrochi, 2005), achievement motivation (Bergner et al., 2010), and self-efficacy (Ng et al., 2008), have been linked with leadership effectiveness and managerial success and may more strongly predict promotions, which demands further empirical consideration. Beyond personality characteristics, promotions are largely influenced by further variables not investigated in this study, such as professional skills, knowledge, and work experience, which in turn determine performance (Gunawan et al., 2022; Schmidt et al., 1986). These variables of course may interact with personality, such as conscientiousness driving knowledge acquisition (Gupta, 2008).

The differential effects for promotions to first-level versus senior-level manager roles may be partly explicable by a correspondence to leadership emergence versus leadership effectiveness, respectively (Judge et al., 2002). For the former, this study’s negative effect for neuroticism converged with the meta-analysis by Judge and colleagues, alongside similar facet-level effects for extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness. For leadership effectiveness, the meta-analysis by Judge and colleagues (2002) showed effects for all five factors. In contrast, this study revealed no effects for personality factors and only for one neuroticism facet and two conscientiousness facets on promotions to senior-level manager roles. This divergence may reflect real differences in how personality is related to leadership effectiveness versus promotions to senior-level manager roles. Performance as a leader is only one amongst many components influencing who is being promoted. In turn, personality has been shown to influence performance in a leadership position (Barrick et al., 2008), but other characteristics and aspects may be more critical for being promoted further higher-up.

To make causal claims, three conditions must be fulfilled: (1) X and Y must be correlated beyond chance (of course, different mediators could potentially cancel each other out so that the main effect may be close to zero, but the correlation between X and one mediator, amongst others, would need to be beyond chance on closer examination), (2) X must precede Y, and (3) all alternative explanations for the relationship must be ruled out (Antonakis et al., 2010). We found that some personality traits and facets predicted promotions beyond chance (first condition). Our study’s longitudinal design fulfils the second condition. The third condition is usually the most difficult to establish (unless a variable is experimentally and randomly manipulated). If variables are stable over time, their relationship with other variables cannot be due to other unobserved variables. Personality traits remain relatively stable at least within the examined timeframe (up to 5 years), especially in the examined age group (Terracciano et al., 2010; but see Nieß & Zacher, 2015, reporting increases in openness to experience following a promotion). To the extent that personality is stable, our results can be interpreted causally; otherwise, they are only correlational. Further, selection bias can represent an alternative explanation for our results (Antonakis et al., 2010). If the company systematically offers personality tests based on participant personality, then our results are only representative for the pre-selected sample and potentially different in the population. But many participants have not been promoted. Therefore, we do not believe that people were systematically selected for the purpose to promote them, but they may differ from the larger population. A combination of repeated measurements of personality and representative sampling would provide more definitive insights into the causal relationship between personality characteristics and promotions, and/or whether personality traits may also be affected within organisational settings by work-related outcomes like promotions (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007; Sutin et al., 2009). To better understand personality processes predicting promotions, candidate mediating factors like job performance and network ties could be investigated in future research (Judge et al., 2002; Ng et al., 2005).

Implications for Practice

Our findings demonstrate the importance of considering personality traits in organisational personnel selection, personnel development, and performance management practices with the aim of generating higher levels of employee performance, amongst others (Gruman & Saks, 2011). We show the merits of assessing and considering personality facets besides only factors to be better able to explain and predict who will be promoted and who not (as called for earlier, e.g. Judge et al., 2002). Thus, we recommend organisations to assess candidate personality on factor and facet levels in selection, development, and placement processes, which may contribute to increasing employee performance, satisfaction, and health, for example via trait activation or moderated by leadership styles (Benoliel & Somech, 2014; Judge & Zapata, 2015; Petasis & Economides, 2020). Furthermore, to our best knowledge, our study is amongst the first to underline the value of not only considering personality promotions globally, but taking into account employees’ job levels and managerial responsibility (see Wilmot & Ones, 2021 for a similar approach investigating personality-performance associations moderated by occupational characteristics). Differences in respective job demands and responsibilities of individual contributor, first-level, and senior-level manager roles lead to diverging predictive effects of personality traits on promotion likelihoods. Understanding such differential relationships can augment the identification and subsequent development of talents who possess the potential and supportive characteristics for higher-level responsibility and leadership positions (Beechler & Woodward, 2009), for example by better aligning job demands and responsibilities with employee characteristics (Kristof, 1996). It is important to stress that the relationship between personality characteristics, job demands, and promotion likelihood is affected by further variables besides job level like job autonomy (Ng et al., 2008), job resources (Bakker et al., 2010), or the business sector in which an employee is situated (Judge et al., 2002). From an individual perspective, employees may take these findings as hints as to which personality characteristics they should preferentially expose within their organisational settings depending on their current and desired future job level, and to embrace personality assessments as a prerequisite to developing compensating skills to improve their work outcomes (as suggested by the selection, optimisation, and compensation (SOC) model, Moghimi et al., 2017), both in the pursuit of promotions as a central aspect of individual career success (Kassis et al., 2017; Moutafi et al., 2007; Seibert & Kraimer, 2001).

Limitations

Some effects were not robust to controlling for employee age, gender, and region of employment. Other effects were significant only when including these variables. This underlines their potential impact, in that these variables may influence personality-promotion associations, as has been shown in earlier studies (Breaugh, 2011; Gensowski, 2018; Ng et al., 2005; Schmidt & Hunter, 2004). Also, most effects in this study were small or medium-sized (according to benchmarks specifically for personality-related findings, Gignac & Szodoraj, 2016). This may mean that personality effects on promotions are indeed relatively small, but could also be explained partly by an absent detrimental impact of common method bias artificially inflating associations (Podsakoff et al., 2003), in contrast to earlier studies (Moutafi et al., 2007; Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). Hence, a further strength of this study was that we did not rely on self-report measures of promotions (as in e.g. Bozionelos, 2004) investigating correlations amongst self-reported variables (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986), but used objective data from the company’s HR information system increasing reliability (as recommended in Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). Our findings may actually be more accurate in terms of effect sizes compared to earlier studies’ results.

Our findings show relatively high levels of generalisability and external validity (Lucas, 2003), as they are based on data from an immediate corporate context including personality assessments within an organisational setting. On the other hand, the extent to which these findings are generalisable may still be limited (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001), for example by the focus on one company in one business sector (wholesale) operating in European and Asian countries. The personality effects found in this study may well differ in other world regions, cultural contexts, and business sectors. For example, different associations of personality traits with leadership outcomes were shown between business, government/military, and student settings (Judge et al., 2002). Diverging effects of personality traits on being in a management position have been found in a Japanese versus a US American sample (Lee & Ohtake, 2012). Thus, the questions examined in this study should be investigated in different cultural contexts and business sectors in follow-up research.

Above, we stated that we avoided selection bias (Antonakis et al., 2010) by only including participants when they completed the personality questionnaire before a promotion. However, there may still have been selection effects, for example in that more promising employees were more likely to be asked to fill in the personality questionnaire sponsored by their direct or indirect manager. This bias should have been reduced in our study as the sample includes many participants who have not been promoted. It is hence unlikely that the personality questionnaire was used primarily in the context of planned promotions.

An open question which we could not take into account in this study is the potential influence of impression management bias of individuals filling in (personality) questionnaires, which may be amplified in corporate contexts (Barrick & Mount, 1996), possibly both before a potential promotion and when settling in a new role after a promotion. Employees may have more or less concrete ideas of which characteristics may be seen as desirable regarding their current or potential future roles and hence bias their responses towards these. This should be investigated further in studies on personality-promotion associations, for example by adding impression management scales (Müller & Moshagen, 2018).

Conclusion

We uniquely investigate the effects of detailed personality facets besides broader factors on promotions in a longitudinal design, differentiating associations by job level in an immediate corporate setting. We partly replicate and extend extant findings (Judge et al., 2002; Moutafi et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2005; Wilmot et al., 2019; Wilmot & Ones, 2019). We show that personality factors and facets differentially contribute to who is being promoted to higher-level individual contributor, first-level, or senior-level manager roles. Neuroticism and its facets tend to decrease the chances of being promoted, whereas some extraversion facets augment the likelihood of a promotion. Openness to experience and conscientiousness contribute positively to and agreeableness tends to hinder promotions to higher-level individual contributor and first-level managerial roles. Thus, these findings overall demonstrate that employee personality influences who will be promoted, and hence has practical implications for both employees and employers, to improve organisational personnel selection, personnel development, and performance management practices by considering personality variables.

Data Availability

The data and analysis script associated with this research are available at https://osf.io/xf2w8/?view_only=15b0bee380a64fb7a692c15068b945aa.

Change history

30 January 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-024-09935-w

Notes

Some effects were not robust to controlling for employee age, gender, and region of employment, whereas other effects were significant only when including these variables, as discussed further below.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

Almlund, M., Duckworth, A. L., Heckman, J., & Kautz, T. (2011). Personality psychology and economics. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education (pp. 1–181). Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53444-6.00001-8

Antonakis, J. (2004). On why “emotional intelligence” will not predict leadership effectiveness beyond IQ or the “big five”: An extension and rejoinder. Organizational Analysis, 12, 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028991

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 1086–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010

Antonakis, J., Day, D. V., & Schyns, B. (2012). Leadership and individual differences: At the cusp of a renaissance. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.05.002

Bakker, A. B., Boyd, C. M., Dollard, M., Gillespie, N., Winefield, A. H., & Stough, C. (2010). The role of personality in the job demands-resources model: A study of Australian academic staff. Career Development International, 15, 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011094050

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1996). Effects of impression management and self-deception on the predictive validity of personality constructs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.3.261

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00160

Bartram, D. (2005). The great eight competencies: A criterion-centric approach to validation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1185–1203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1185

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. Free Press.

Beechler, S., & Woodward, I. C. (2009). The global “war for talent.” Journal of International Management, 15, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2009.01.002

Benoliel, P., & Somech, A. (2014). The health and performance effects of participative leadership: Exploring the moderating role of the Big Five personality dimensions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23, 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.717689

Bergner, S., Neubauer, A. C., & Kreuzthaler, A. (2010). Broad and narrow personality traits for predicting managerial success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19, 177–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320902819728

Blake, A. B., Luu, V. H., Petrenko, O. V., Gardner, W. L., Moergen, K. J., & Ezerins, M. E. (2022). Let’s agree about nice leaders: A literature review and meta-analysis of agreeableness and its relationship with leadership outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 33, 101593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101593

Bleidorn, W., Schwaba, T., Zheng, A., Hopwood, C. J., Sosa, S. S., Roberts, B. W., & Briley, D. A. (2022). Personality stability and change: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 148, 588–619. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000365

Bozionelos, N. (2004). The relationship between disposition and career success: A British study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1348/0963179041752682

Breaugh, J. A. (2011). Modeling the managerial promotion process. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26, 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111124818

Brown, S. D., Lent, R. W., Telander, K., & Tramayne, S. (2011). Social cognitive career theory, conscientiousness, and work performance: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.11.009

Caspi, A., Elder, G. H., & Bem, D. J. (1988). Moving away from the world: Life-course patterns of shy children. Developmental Psychology, 24, 824–831. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.24.6.824

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240133762_Neo_PIR_professional_manual

Curran, P. J., & Hussong, A. M. (2009). Integrative data analysis: The simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychological Methods, 14, 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015914

Danner, D., Rammstedt, B., Bluemke, M., Lechner, C., Berres, S., Knopf, T., ... & John, O. P. (2019). The German Big Five Inventory 2: Measuring five personality domains and 15 facets. Diagnostica, 65, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000218

DeYoung, C. G., Quilty, L. C., & Peterson, J. B. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.880

Edelman, P., & van Knippenberg, D. (2018). Emotional intelligence, management of subordinate’s emotions, and leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39, 592–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-04-2018-0154

Ensari, N., Riggio, R. E., Christian, J., & Carslaw, G. (2011). Who emerges as a leader? Meta-analyses of individual differences as predictors of leadership emergence. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 532–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.017

Furnham, A., & Crump, J. (2015). Personality and management level: Traits that differentiate leadership levels. Psychology, 6, 549–559. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2015.65053

Gensowski, M. (2018). Personality, IQ, and lifetime earnings. Labour Economics, 51, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.12.004

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

Gruman, J. A., & Saks, A. M. (2011). Performance management and employee engagement. Human Resource Management Review, 21, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.09.004

Gunawan, M. R., Tirtayasa, S., & Rambe, M. F. (2022). The influence of competence and work experience on position promotion through job performance at PT. Bank Sumut Head Office. Jurnal Mantik, 6, 321–329.

Gupta, B. (2008). Role of personality in knowledge sharing and knowledge acquisition behavior. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 34, 143–149.

Haehner, P., Kritzler, S., Fassbender, I., & Luhmann, M. (2022). Stability and change of perceived characteristics of major life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122, 1098–1116. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000394

Holman, D. J., & Hughes, D. J. (2021). Transactions between Big-5 personality traits and job characteristics across 20 years. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94, 762–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12332

Howard, A., & Bray, D. W. (1990). Predictions of managerial success over time: Lessons from the management progress study. In K. E. Clark & M. B. Clark (Eds.), Measures of leadership (pp. 113–130). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-97354-003

Hülsheger, U. R., Specht, E., & Spinath, F. M. (2006). Validität des BIP und des NEO-PI-R: Wie geeignet sind ein berufsbezogener und ein nicht explizit berufsbezogener Persönlichkeitstest zur Erklärung von Berufserfolg? Zeitschrift Für Arbeits-Und Organisationspsychologie, 50, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089.50.3.135

Judge, T. A., & Zapata, C. P. (2015). The person–situation debate revisited: Effect of situation strength and trait activation on the validity of the Big Five personality traits in predicting job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1149–1179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0837

Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz, R. D., Jr. (1995). An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel Psychology, 48, 485–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01767.x

Judge, T. A., Higgins, C., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick, M. R. (1999). The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2007). Personality and career success. In H. P. Gunz & M. Peiperl (Eds.), Handbook of Career Studies (pp. 59–78). Sage Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976107.n4

Kassis, M., Schmidt, S. L., Schreyer, D., & Torgler, B. (2017). Who gets promoted? Personality factors leading to promotion in highly structured work environments: Evidence from a German professional football club. Applied Economics Letters, 24, 1222–1227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2016.1267841

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x

Kurz, R. H. [chair] (2023a). The Periodic Table of Personality at Work. [Symposium] European Congress of Psychology, Brighton, UK.

Kurz, R. H. [chair] (2023b). New Horizons in Personality Assessment. [Symposium] Congress of the European Federation of Psychologists' Associations, Padova, Italy.

Lee, S., & Ohtake, F. (2012). The effect of personality traits and behavioral characteristics on schooling, earnings and career promotion. Journal of Behavioral Economics and Finance, 5, 231–238. https://doi.org/10.11167/jbef.5.231

Lucas, J. W. (2003). Theory-testing, generalization, and the problem of external validity. Sociological Theory, 21, 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9558.00187

Melamed, T. (1996). Validation of a stage model of career success. Applied Psychology, 45, 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1996.tb00848.x

Moghimi, D., Zacher, H., Scheibe, S., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2017). The selection, optimization, and compensation model in the work context: A systematic review and meta-analysis of two decades of research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 247–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2108

Morgeson, F. P., Campion, M. A., & Levashina, J. (2009). Why don’t you just show me? Performance interviews for skill-based promotions. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17, 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2009.00463.x

Mount, M. K., & Barrick, M. R. (1995). The big five personality dimensions: Implications for research and practice in human resources management. In G. R. Ferris & K. M. Rollins (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 153–200). JAI Press.

Moutafi, J., Furnham, A., & Crump, J. (2007). Is managerial level related to personality?. British Journal of Management, 18, 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00511.x

Müller, S., & Moshagen, M. (2018). Controlling for response bias in self-ratings of personality: A comparison of impression management scales and the overclaiming technique. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101, 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1451870

Mumford, T. V., Campion, M. A., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). The leadership skills strataplex: Leadership skill requirements across organizational levels. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.01.005

Mussel, P., Winter, C., Gelleri, P., & Schuler, H. (2011). Explicating the openness to experience construct and its subdimensions and facets in a work setting. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 19, 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2011.00542.x

Ng, T. W., Eby, L. T., Sorensen, K. L., & Feldman, D. C. (2005). Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 58, 367–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00515.x

Ng, K.-Y., Ang, S., & Chan, K.-Y. (2008). Personality and leader effectiveness: A moderated mediation model of leadership self-efficacy, job demands, and job autonomy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.733

Nieß, C., & Zacher, H. (2015). Openness to experience as a predictor and outcome of upward job changes into managerial and professional positions. PLoS ONE, 10, e0131115. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131115

Palaiou, K., & Furnham, A. (2014). Are bosses unique? Personality facet differences between CEOs and staff in five work sectors. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 66, 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000010

Petasis, A., & Economides, O. (2020). The big five personality traits, occupational stress, and job satisfaction. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2020.5.4.410

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organization research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12, 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.https://www.R-project.org/

Reichard, R. J., Riggio, R. E., Guerin, D. W., Oliver, P. H., Gottfried, A. W., & Gottfried, A. E. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of relationships between adolescent personality and intelligence with adult leader emergence and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.005

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

Rosete, D., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Emotional intelligence and its relationship to workplace performance outcomes of leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26, 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510607871

Schakel, L., Smid, N., & Jaganjac, A. (2012). Reflector Big Five Personality Professional Manual. PI Company BV.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. (2004). General mental ability in the world of work: Occupational attainment and job performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.162

Schmidt, F. L., Hunter, J. E., & Outerbridge, A. N. (1986). Impact of job experience and ability on job knowledge, work sample performance, and supervisory ratings of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.432

Seibert, S. E., & Kraimer, M. L. (2001). The Five-Factor model of personality and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1757

Spark, A., Stansmore, T., & O’Connor, P. (2018). The failure of introverts to emerge as leaders: The role of forecasted affect. Personality and Individual Differences, 121, 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.026

Spark, A., O’Connor, P. J., Jimmieson, N. L., & Niessen, C. (2022). Is the transition to formal leadership caused by trait extraversion? A counterfactual hazard analysis using two large panel datasets. The Leadership Quarterly, 33, 101565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101565

Spector, P. E., Schneider, J. R., Vance, C. A., & Hezlett, S. A. (2000). The relation of cognitive ability and personality traits to assessment center performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1474–1491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02531.x

Speer, A. B., Siver, S. R., & Christiansen, N. D. (2020). Applying theory to the black box: A model for empirically scoring biodata. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 28, 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12271

Sutin, A. R., Costa, P. T., Miech, R., & Eaton, W. W. (2009). Personality and career success: Concurrent and longitudinal relations. European Journal of Personality, 23, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.704

Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2010). Intra-individual change in personality stability and age. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.09.006

Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500

United Nations (2022). Standard country or area codes for statistical use (M49), https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/

Wilmot, M. P., & Ones, D. S. (2019). A century of research on conscientiousness at work. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 23004–23010. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908430116

Wilmot, M. P., & Ones, D. S. (2021). Occupational characteristics moderate personality–performance relations in major occupational groups. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 131, 103665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103655

Wilmot, M. P., Wanberg, C. R., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Ones, D. S. (2019). Extraversion advantages at work: A quantitative review and synthesis of the meta-analytic evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104, 1447–1470. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000415

Wilms, R., Mäthner, E., Winnen, L., & Lanwehr, R. (2021). Omitted variable bias: A threat to estimating causal relationships. Methods in Psychology, 5, 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2021.100075