Abstract

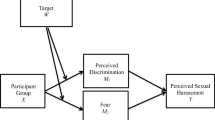

The approach–avoidance perspective provides a theoretical framework through which the dynamic nature of sexual harassment can be understood meaningfully in a workplace context. Rather than being purely threat or incentive, potentially harassing situations may contain elements of both, leading to approach and avoidance attitudes. Across two studies, we explore how three factors (relative attractiveness, gender, and relationship status) affect approach–avoidance attitudes in the target (study 1) and initiator (study 2), and how these attitudes affect (a) labeling the interaction as sexual harassment and (b) forecasts of filing a complaint. Results indicate that the three factors affect approach and avoidance attitudes for both targets and initiators, and that these attitudes mediate both the effect of labeling the interaction as sexual harassment and forecasts of filing a complaint. Implications for managers, human resources personnel, and other third parties who manage sexual harassment disputes are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The data provided an opportunity to disentangle the effects of other attractiveness from self-attractiveness within relative attractiveness. To examine this, we ran two moderated moderation tests for single participants looking at other-attractiveness (X) moderated by self-attractiveness (W) and gender (Z) on approach attitudes (Y) in one test and avoidance attitudes (Y) in another test. Similarly, we ran two moderated moderation tests for married participants looking at other-attractiveness (X) moderated by self-attractiveness (W) and gender (Z) on approach attitudes (Y) in one test and avoidance attitudes (Y) in another test. Each of the four tests yielded non-significant main effects for other-attractiveness, but two of the tests yielded significant 2-way interactions involving other-attractiveness and self-attractiveness, and one test yielded a significant three-way interaction (involving other-attractiveness, self-attractiveness, and gender). The full results of the four moderated moderation tests as well as a response surface analyses are available in the supplemental materials. Findings supported the use of relative attractiveness as the appropriate metric to test our hypotheses.

In an alternative analysis, we used the bootstrapping method for estimating direct and indirect effects for a simple (unmoderated) parallel serial mediation with a multicategorical antecedent (PROCESS: Hayes, 2018a), controlling for gender and marital status. Relative attractiveness was entered as the predictor variable using the indicator coding approach with “the initiator higher in attractiveness” condition as the reference group (Hayes & Preacher, 2014) using Model 80 with 10,000 bootstrap samples. We found that relative attractiveness significantly affected approach attitudes when the initiator was higher than the participant in attractiveness compared with when he/she was matched in attractiveness (i.e., X1) (b = − 0.20, p = .019, 95% CI = − 0.36 to − 0.03) and compared with when the initiator was lower than the participant in attractiveness (i.e., X2) (b = − 0.29, p = .001, 95% CI = − 0.46 to − 0.12). At the same time, relative attractiveness significantly affected avoidance attitudes for X1 (b = 0.39, p = .001, 95% CI = 0.16 to 0.62), but not for X2 (b = 0.14, p = .222, 95% CI = − 0.08 to 0.36). Approach attitudes were negatively related to labeling the behavior as sexual harassment (b = − 0.36, p < .001, 95% CI = − 0.53 to − 0.19) and avoidance attitudes positively related to labeling the behavior as sexual harassment (b = .44, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.32 to 0.57). Finally, labeling the behavior as sexual harassment was positively related to forecasts of filing a formal complaint (b = .41, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.31 to 0.51). Thus, we found a significant indirect effect of relative attractiveness on forecasts of filing a complaint through approach attitudes then labeling the interaction as sexual harassment for X1 (effect = .03, 95% CI [0.00, 0.07]) and X2 (effect = .04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.09]). Simultaneously, we found a significant indirect effect through avoidance attitudes then labeling the interaction as sexual harassment for X2 (effect = 0.07, 95% CI [0.03, 0.13]), but not for X1 (effect = 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.07]).

We also used the bootstrapping method for estimating direct and indirect effects for moderated serial mediation with a multicategorical antecedent (PROCESS: Hayes, 2018a) and ran separate models for single and married participants. Relative attractiveness was entered as the predictor variable using the indicator coding approach with “the initiator higher in attractiveness” condition as the reference group (Hayes & Preacher, 2014) with gender as the moderator using Model 86 with 10,000 bootstrap samples. Results are provided in the supplemental materials.

In an alternative analysis, we used the bootstrapping method for estimating direct and indirect effects for a simple (unmoderated) parallel serial mediation with a multicategorical antecedent (PROCESS: Hayes, 2018a), controlling for gender, and marital status. We used Model 80 with 10,000 bootstrap samples. We found that relative attractiveness did not significantly affect approach attitudes when the target was higher than the participant in attractiveness compared with when he/she was matched in attractiveness (i.e., X1), or compared with when the target was lower than the participant in attractiveness (i.e., X2) (all p > .05). At the same time, relative attractiveness did not significantly affect avoidance attitudes for X1, nor for X2 (all p > .05). However, approach attitudes were positively related to labeling the behavior as sexual harassment (b = 0.14, p = .001, 95% CI = 0.06 to 0.21), as were avoidance attitudes (b = 0.73, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.63 to 0.82). Finally, labeling the behavior as sexual harassment was positively related to forecasts of filing a formal complaint (b = 0.14, p = .035, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.28). Thus, we found a significant indirect effect of relative attractiveness on forecasts of filing a complaint through approach attitudes then labeling the interaction as sexual harassment for X1 (effect = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.00]), and for X2 (effect = 0.00, 95% CI [0.00, 0.01]). Simultaneously, we did not find a significant indirect effect through avoidance attitudes then labeling the interaction as sexual harassment for X1 (effect = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.03]), nor for X2 (effect = − 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.05, 0.01]), offering support for Hypothesis 4c but not for Hypothesis 4d.

We also used the bootstrapping method for estimating direct and indirect effects for moderated serial mediation with a multicategorical antecedent (PROCESS: Hayes, 2018a) and ran separate models for single and married participants. Relative attractiveness was entered as the predictor variable using the indicator coding approach with “the target higher in attractiveness” condition as the reference group (Hayes & Preacher, 2014) with gender as the moderator using Model 86 with 10,000 bootstrap samples. Results are provided in the supplemental materials.

References

Abbey, A. (1982). Sex differences in attributions for friendly behavior: Do males misperceive females’ friendliness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 830–838.

Agthe, M., Sporrle, M., & Maner, J. K. (2010). Don’t hate me because I’m beautiful: Anti-attractiveness bias in organizational evaluation and decision making. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 1151–1154.

Anderson, C., John, O. P., Keltner, D., & Kring, A. (2001). Social status in naturalistic face-to-face groups: Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in men and women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 116–132.

Bargh, J. A., Raymond, P., Pryor, J. B., & Strack, F. (1995). Attractiveness of the underling: An automatic power ➞ sex association and its consequences for sexual harassment and aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 768–781.

Berdahl, J. L. (2007). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. Academy of Management Review, 32, 641–658.

Bergman, M. E., Langhout, R. D., Palmieri, P. A., Cortina, L. M., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). The (un)reasonableness of reporting: Antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 230–242.

Berscheid, E., Dion, K., Walster, E., & Walster, G. W. (1971). Physical attractiveness and dating choice: A test of the matching hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 173–189.

Browne, K. R. (2006). Sex, power, and dominance: The evolutionary psychology of sexual harassment. Managerial and Decision Economics, 27, 145–158.

Buss, D. M. (2016). The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating. New York: Basic books.

Cartar, L., Hicks, M., & Slane, S. (1996). Women’s reactions to hypothetical male sexual touch as a function of initiator attractiveness and level of coercion. Sex Roles, 35, 737–750.

Carver, C. S. (1996). Emergent integration in contemporary personality psychology. Journal of Research in Personality, 30, 319–334.

Castello, W. A., Wuensch, K. L., & Moore, C. H. (1990). Effects of physical attractiveness of the plaintiff and defendant in sexual harassment judgments. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 5, 547–562.

Clair, R. (1994). Hegemony and harassment: A discursive practice. In Bingham’s (Ed.), Conceptualizing Sexual Harassment as Discursive Practice (pp. 59–70). Westport: Praeger.

Clark, R. D., & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2, 39–55.

Corr, P. J., & Jackson, C. J. (2001). Dimensions of perceived sexual harassment: Effects of gender, and status/liking of source. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 525–539.

Cortina, L. M., & Wasti, S. A. (2005). Profiles in coping: Responses to sexual harassment across persons, organizations, and culture. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 182–192.

DePue, R. A. (1995). Neurobiological factors in personality and depression. European Journal of Personality, 9, 413–439.

Dougherty, T. W., Turban, D. B., Olson, D. E., Dwyer, P. D., & Lapreze, M. W. (1996). Factors affecting perceptions of workplace sexual harassment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 489–501.

Edwards, J. R. (2002). Alternatives to differences scores: Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In F. Drasgow & N. W. Schmitt (Eds.), Advances in measurement and data analysis (pp. 350–400). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Elliot, A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 111–116.

Elliot, A. J., & Sheldon, K. M. (1997). Avoidance achievement motivation: A personal goals analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 171–185.

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 804–818.

Ferris, D. L., Yan, M., Lim, V. K., Chen, Y., & Fatimah, S. (2016). An approach–avoidance framework of workplace aggression. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 1777–1800.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Fitzgerald, L. F., & Ormerod, A. J. (1991). Perceptions of sexual harassment: The influence of gender and academic context. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 281–294.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 578–589.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Magley, V. J., Drasgow, F., & Waldo, C. R. (1999). Measuring sexual harassment in the military: The Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ-DoD). Military Psychology, 11, 243–263.

Gable, S. L., & Strachman, A. (2008). Approaching social rewards and avoiding social punishments: Appetitive and aversive social motivation. In J. Y. Shah & W. L. Gardner (Eds.), Handbook of motivation science (pp. 561–575). New York: Guilford Press.

Galinsky, A. D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Magee, J. C. (2003). From power to action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 453–466.

Golden, J. H., Johnson, C. A., & Lopez, R. A. (2002). Sexual harassment in the workplace: Exploring the effects of attractiveness on perception of harassment. Sex Roles, 45, 767–783.

Gray, J. A. (1990). Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition and Emotion, 4, 269–288.

Gutek, B. A. (1995). How subjective is sexual harassment? An examination of rater effects. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 447–467.

Hayes, A. F. (2018a). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2018b). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85, 4–40.

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67, 451–470.

Hendrix, W. H. (2000). Perceptions of sexual harassment by student-employee classification, marital status, and female racial classification. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 15, 529–544.

Hershcovis, M. S., & Barling, J. (2010). Comparing victim attributions and outcomes for work-place aggression and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 874–888.

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280–1300.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Ilies, R., Hauserman, N., Schwochau, S., & Stibal, J. (2003). Reported incidence rates of work-related sexual harassment in the United States: Using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Personnel Psychology, 56, 607–631.

Jones, T. S., & Remland, M. S. (1992). Sources of variability in perceptions of and responses to sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 27, 121–141.

Karremans, J. C., & Verwijmeren, T. (2008). Mimicking attractive opposite-sex others: The role of romantic relationship status. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 939–950.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110, 265–284.

Kenrick, D. T., Neuberg, S. L., Zierk, K. L., & Krones, J. M. (1994). Evolution and social cognition: Contrast effects as a function of sex, dominance, and physical attractiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 210–217.

Knapp, D. E., Hogue, M., & Pierce, C. A. (2019). A gateway theory-based model of the escalation of severity of sexually harassing behavior in organizations. Journal of Managerial Issues, 31, 198–215.

Koranyi, N., & Rothermund, K. (2012). When the grass on the other side of the fence doesn’t matter: Reciprocal romantic interest neutralizes attentional bias towards attractive alternatives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 186–191.

Koss, M. P., Goodman, L. A., Browne, A., Fitzgerald, L. F., Keita, G. P., & Russo, N. F. (1994). No safe haven: Male violence against women at home, at work, and in the community. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individual's fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

Kunstman, J. W., & Maner, J. K. (2011). Sexual overperception: Power, mating motives, and biases in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 282–294.

Lee, J., Heilmann, S. G., & Near, J. P. (2004). Blowing the whistle on sexual harassment: Test of a model of predictors and outcomes. Human Relations, 57, 297–322.

Lee, L., Loewenstein, G., Ariely, D., Hong, J., & Young, J. (2008). If I’m not hot, are you hot or not? Physical-attractiveness evaluations and dating preferences as a function of one’s own attractiveness. Psychological Science, 19, 669–677.

Madera, J. M., Podratz, K. E., King, E. B., & Hebl, M. R. (2007). Schematic responses to sexual harassment complainants: The influence of gender and physical attractiveness. Sex Roles, 56, 223–230.

Maner, J. K., Gailliot, M. T., Rouby, D. A., & Miller, S. L. (2007). Can’t take my eyes off you: Attentional adhesion to mates and rivals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 389–401.

Maner, J. K., Gailliot, M. T., & Miller, S. L. (2009). The implicit cognition of relationship maintenance: Inattention to attractive alternatives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 174–179.

Markman, K. D., & McMullen, M. N. (2003). A reflection and evaluation model of comparative thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 244–267.

McCabe, M. P., & Hardman, L. (2005). Attitudes and perceptions of workers to sexual harassment. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145, 719–740.

Miller, N. E. (1959). Liberalization of basic S-R concepts: Extensions to conflict behavior, motivation, and social learning. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of science, Vol. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Miller, S. L., & Maner, J. K. (2010). Evolution and relationship maintenance: Fertility cues lead committed men to devalue relationship alternatives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 1081–1084.

Miller, S. L., Prokosch, M. L., & Maner, J. K. (2012). Relationship maintenance and biases on the line bisection task: Attractive alternatives, asymmetrical cortical activity, and approach-avoidance motivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 566–569.

Montoya, R. M. (2008). I’m hot, so I say you’re not: The influence of objective physical attractiveness on mate selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1315–1329.

O’Connor, M., Gutek, B. A., Stockdale, M., Geer, T. M., & Melancon, R. (2004). Explaining sexual harassment judgments: Looking beyond gender of the rater. Law and Human Behavior, 28, 69–95.

O’Leary-Kelly, A. M., Paetzold, R. L., & Griffin, R. W. (2000). Sexual harassment as aggressive behavior: An actor-based perspective. Academy of Management Review, 25, 372–388.

Olapegba, P. O. (2004). Perceived sexual harassment as a consequence of psychosocial factors. IFE Psychologia: An International Journal, 12, 40–48.

Petit, W. E., & Ford, T. E. (2015). Effect of relationship status on perceptions of physical attractiveness for alternative partners. Personal Relationships, 22, 348–355.

Pina, A., & Gannon, T. A. (2012). An overview of the literature on antecedents, perceptions, and behavioral consequences of sexual harassment. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 18, 209–232.

Popovich, P. M., Gehlauf, D. N., Jolton, J. A., Everton, W. J., Godinho, R. M., Mastrangelo, P. M., & Somers, J. M. (1996). Physical attractiveness and sexual harassment: Does every picture tell a story or every story draw a picture? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26, 520–542.

Pryor, J. B., & Stoller, L. M. (1994). Sexual cognition processes in men high in the likelihood to sexually harass. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(2), 163–169.

Rotundo, M., Nguyen, D., & Sackett, P. R. (2001). A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 914–922.

Settles, I. H., Buchanan, N. T., Yap, S. C. Y., & Harrell, Z. A. T. (2014). Sex differences in outcomes and harasser characteristics associated with frightening sexual harassment appraisals. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19, 133–142.

Shaw Taylor, L., Fiore, A. T., Mendelsohn, G. A., & Cheshire, C. (2011). “Out of my league”: A real-world test of the matching hypothesis. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 942–954.

Sheets, V. L., & Braver, S. L. (1999). Organizational status and perceived sexual harassment: Detecting the mediators of a null effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 1159–1171.

Simpson, J. A., & Gangestad, S. W. (1991). Individual differences in sociosexuality: Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 870–883.

Simpson, J. A., Lerma, M., & Gangestad, S. W. (1990). Perception of physical attractiveness: Mechanisms involved in the maintenance of romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1192–1201.

Sprecher, S., & Hatfield, E. (2009). Matching hypothesis. In H. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Studd, M. V., & Gattiker, U. E. (1991). The evolutionary psychology of sexual harassment in organizations. Ethology and Sociobiology, 12, 249–290.

Swann, W. B. (2007). Self-verification theory. In E. Roy, F. Baumeister, & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Social Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 849–853). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (1980, November). Final amendment to guidelines on discrimination because of sex under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended. 29 CFR Part 1604. Federal Register, 45, 74675–74677.

van Straaten, I., Engels, R. C. M. E., Finkenauer, C., & Holland, R. W. (2009). Meeting your match: How attractiveness similarity affects approach behavior in mixed-sex dyads. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 685–697.

Wasti, S. A., & Cortina, L. M. (2002). Coping in context: Sociocultural determinants of responses to sexual harassment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 394–405.

Wiener, R. L., & Hurt, L. E. (2000). How do people evaluate social sexual conduct at work? A psychological model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 75–85.

Williams, C. L., Giuffre, P. A., & Dellinger, K. (1999). Sexuality in the workplace: Organizational control, sexual harassment, and the pursuit of pleasure. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 73–93.

Willness, C. R., Steel, P., & Lee, K. (2007). A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60, 127–162.

Wuensch, K. L., & Moore, C. H. (2004). Effects of physical attractiveness on evaluations of a male employee’s allegation of sexual harassment by his female employer. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144, 207–217.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 90 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Study 1

Imagine that, as a college student at a major university, you are hoping to pursue an MBA when you graduate. You recently “lucked” into an incredible job opportunity when you were hired by a prominent downtown firm to work part-time as a market researcher. You are really excited because of the valuable experience you will be getting, experience that puts you well ahead of the other pre-MBA students. As a bonus, you find that you really enjoy the work you are doing and you enjoy most of the people that you work with.

One day, after about 2 months of working there, you are working in the conference room instead of your usual cubicle for some privacy. Mike (Michelle), a 28-year-old Director at the firm, pictured below (high, moderate, low attractiveness), enters to ask you a question about the project you have been working on. He (she) shuts the door and sits next to you. As you begin to answer his (her) question, he (she) reaches over and starts rubbing your thigh. He (She) tells you that he (she) would really like to get to know you better. When you refuse, he (she) repeats his (her) offer. You do not know what to think. You never expected this kind of behavior at work—especially at a big firm. This is not the first time he has (she has) made a pass at you, even though you have let him (her) know that you are not interested.

Study 2

Imagine that, as a Director in the marketing department at a prominent downtown firm, you are hoping to be promoted next year. You recently “lucked” into an incredible opportunity to launch a major new product. You are really excited because of the valuable experience you will be getting, experience that puts you well ahead of your other colleagues who are being considered for the same promotion. As a bonus, you find that you really enjoy the work you are doing on this new project, and you enjoy most of the people that you work with.

One day, after about 2 months of working there, Mike (Michelle), pictured below (high, moderate, low attractiveness), a junior Marketing Assistant, is working in the conference room instead of his (her) usual cubicle for some privacy. You enter to ask him (her) a question about the project he has (she has) been working on. You shut the door and sit next to him (her). As he (she) begins to answer your question, you reach over and touch his (her) thigh. You tell him (her) that you would really like to get to know him (her) better. When he (she) refuses, you repeat your offer. This is not the first time you have made a pass at him (her), even though he has (she has) let you know that he is (she is) not interested.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sillito Walker, S.D., Bonner, B.L. An Approach–Avoidance Lens on Sexual Harassment: The Effects of Relative Attractiveness, Gender, Relationship Status, and Role. J Bus Psychol 37, 127–150 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09729-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09729-w