Abstract

This research developed and evaluated a measure to examine fire-specific constructs relevant to fire misuse. In the first study, using UK community members asked to disclose deliberate firesetting, we tested a large pool of theoretically informed questionnaire items. First, we found that 1 in 10 adults reported setting a deliberate fire that they had not been apprehended for. Then, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses suggested an eight-factor measure with broader coverage of theoretically-informed risk factors, relative to previous measures, and acceptable test item validity and robust internal consistencies. In the second study, we tested the Firesetting Questionnaire with imprisoned men who held a record of firesetting and imprisoned and community comparisons. The findings illustrated psychometric robustness. Our results suggest that the Firesetting Questionnaire has the potential to be a useful clinical tool for highlighting fire-specific treatment needs and informing clinical formulation and associated risk management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Deliberate firesetting is an international public health issue of vast proportions (Tyler et al., 2019). Latest available statistics from the US National Fire Protection Association suggest that more than 250,000 deliberate firesetting incidents were responded to by fire services over the five-year term from 2014 to 2018 (Campbell, 2021). These incidents were annually responsible for around 1,350 civilian casualties, including 400 deaths, and $815 million costs in direct property damage (Campbell, 2021). Yet, despite the huge human and economic costs associated with deliberate firesetting, compared with other offending behaviors such as sexual offending and violence, empirical research examining deliberate firesetting is embryonic. To date, there are no established assessments available for assessing deliberate firesetting risk factors which makes it difficult to establish convincing evidence of ‘what works’ to reduce deliberate firesetting behavior (Fritzon et al., 2013; Palmer et al., 2007).

Low levels of research in this area appear to have resulted from a long-standing assumption that individuals who deliberately fireset are offence ‘generalists’ who do not require specialist psychological assessment or intervention. However, psychological research shows that males who have set deliberate fires are psychologically different to other matched males who have offended; exhibiting, in particular, higher endorsement of fire-specific variables (e.g., serious fire interest and identification with fire; Gannon et al., 2013; Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015). These variables, amongst others, are conceptualized in the most recent empirically-informed theoretical framework examining the development and maintenance of firesetting (i.e., the Multi-Trajectory Theory of Adult Firesetting [M-TTAF]; Gannon et al., 2012; Gannon et al., 2022) as dynamic risk factors. Within the M-TTAF, three key fire-specific dynamic risk factors are emphasized as being important in the etiology of deliberate firesetting. These are: (1) an inappropriate interest in fire or fire misuse, (2) inappropriate fire scripts (i.e., cognitive rules in which fire is the preferred mechanism for achieving particular goals such as crime concealment or communication), and (3) attitudes that support deliberate firesetting such as believing that fire is controllable. Although these factors are conceptualized within the M-TTAF (Gannon et al., 2012) as being independent, the pattern of these fire-specific features are predicted to be important for the individualized formulation of firesetting behavior. Since fire-specific interests, cognitive associations, and attitudes appear to represent key risk factors for firesetting behavior, it critical that professionals are able to accurately assess these variables to inform clinical formulation and associated risk management. To date, very few questionnaires have been constructed to examine fire-specific dynamic risk factors in adults.

Perhaps the best-known questionnaires developed to examine fire-specific dynamic risk factors are the Fire-setting Assessment Schedule and the Fire Interest Rating Scale which were developed some decades ago by Murphy and Clare (1996). The Fire-setting Assessment Schedule contains 32 items and was developed to examine the events, affect, and cognitions associated with firesetting incidents via eight constructs covering themes such as self-stimulation (“I felt that starting fires was the most exciting thing I could do”) and social attention (“I started fires to make people pay attention and listen to me”). However, this schedule was constructed for use with individuals holding intellectual disabilities and has not been widely validated with other populations. The Fire Interest Rating Scale is made up of 14 fire-specific situations (e.g., “watching a house burn down”) that participants are requested to assess on a 7-point Likert scale regarding their affective response. Initially developed with individuals experiencing intellectual disabilities, this questionnaire has been used more widely with adult firesetting populations to measure extent of inappropriate fire interest (Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2016; Swaffer et al., 2001) and has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.82; Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2016). Another measure developed, in part, to assess fire interest is the Fire Setting Scale (Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012). This measure comprises 20 items and was originally developed to assess fire interest (10 items; “I find fire intriguing”) and antisocial behavior (10 items; “I am a rule breaker”) in community members. Although the scale holds good discriminative ability between community members who self-report deliberate firesetting and those who do not (Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2015, 2016; Barrowcliffe et al., 2022; Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012), it has yet to be validated with apprehended populations. The Fire Attitude Scale (Muckley, 1997) consists of 20 items developed to examine fire supportive attitudes (e.g., “setting just a small fire can make you feel a lot better”). It was originally developed in the UK in the context of an intervention provided by Fire and Rescue but has been adopted by clinicians to inform assessment and intervention with adults who have set fires (Collins, Barnoux, & Langdon, 2021; Taylor & Thorne, 2019).

In 2015, Ó Ciardha, Barnoux and colleagues set out to improve construct measurement in firesetting assessment through combining items from the Fire Interest Rating Scale (Murphy & Clare, 1996), and the Fire Attitude Scale (Muckley, 1997) with a recently constructed Identification with Fire Questionnaire (Gannon et al., 2011) in order to assess the number of distinct constructs measured by these scales. The Identification with Fire Questionnaire is comprised of 10 items (e.g., “fire is an important part of my identity”) designed to measure personal identification with fire. After factor analyzing the items from the three measures using a sample of 234 imprisoned males (half of whom had a history of setting deliberate fires), five distinct constructs were initially reported: identification with fire (as per Gannon et al., 2011), serious fire interest (inappropriate interest in highly destructive and dangerous fires), everyday fire interest (inappropriate interest in everyday fire-related phenomena), fire safety awareness (perceived lack of fire safety knowledge), and firesetting as normal (perception of fire misuse being common). These five constructs were later pruned down to four (named the Four Factor Fire Scales; Ó Ciardha, Tyler, & Gannon, 2015) for clinical use after the everyday fire interest construct failed to discriminate between imprisoned individuals who had a history of deliberate firesetting and those who did not (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015). The final Four Factor Fire Scales assessment was normed across mixed gender forensic health and prison samples (N = 565) to provide practitioners with a reliable set of comparable data with which to compare assessment scores (Ó Ciardha, Tyler, & Gannon, 2015).

While the Five and Four Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015; Ó Ciardha, Tyler, & Gannon, 2015) have enabled researchers and clinicians to assess fire-specific factors in a more meaningful way using pre-existing scales, there are key limitations. Most notable, perhaps, is that the scales do not contain items that reflect current firesetting theory since the majority of underpinning items stem from scales developed in the 1990s (i.e., The Fire Interest Rating Scale, Murphy & Clare, 1996; The Fire Attitude Scale, Muckley 1997). The most obvious caveat relates to the absence of items that assess inappropriate fire scripts (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Gannon et al., 2012; Gannon et al., 2022). Fire scripts refer to a learnt set of cognitive rules regarding how fire is perceived and used (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Gannon et al., 2022). Within westernized cultures, when fire scripts are appropriate, fire is typically perceived to be comforting or invigorating in particular contexts (e.g., at a religious celebration, or at organized bonfires where fire is used safely; Gannon et al., 2022). An inappropriate fire script, on the other hand, may result in fire being misused preferentially in order to achieve particular goals such as crime concealment or communication (e.g., an individual may perceive fire as being the best way to destroy evidence or cope with distressing situations; Butler & Gannon, 2015; Gannon et al., 2012). Such scripts can exist either in addition to—or in the absence of—an inappropriate fire interest. A further clear caveat of the Five and Four Factor Fire Scales relates to the lack of item diversity within particular domains. For example, although there are items that assess attitudes that support deliberate firesetting, these focus on the concept of fire normalization and do not tap other attitudes proposed to be etiological such as believing that fire is controllable (see Gannon et al., 2012; Ó Ciardha & Gannon, 2012). Finally, neither the Five or Four Factor Fire Scales measure has been appropriately validated with samples of unapprehended individuals who have reported setting deliberate fires in the community.

The prevalence of unapprehended firesetting in the community has almost exclusively been examined via a series of small-scale studies in the UK (Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012; Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2015, 2016; see also Johnston 2022). Members of the community were invited to anonymously self-report whether they had ever set a deliberate fire since the age of 10 years that they had never been apprehended for. Across these studies, between 11% and 18% of community members self-reported having engaged in deliberate firesetting. Barrowcliffe and Gannon’s (2015) study was the most methodologically rigorous regarding sampling, revealing the prevalence of individuals who had set a deliberate fire to be 11.5%. Individuals across all three studies were asked to provide relevant details concerning firesetting characteristics (e.g., materials used to start the fire) and motivations. In these studies, popular measures of fire-specific dynamic risk factors were used (e.g., the Fire Interest Rating Scale, Murphy & Clare, 1996; the Fire Attitude Scale, Muckley 1997; the Identification with Fire Questionnaire Gannon et al., 2011) with varying levels of discriminatory success. However, these measures were never examined using the Five or Four Factor Fire Scales’ (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015, 2016) scoring algorithms.

The aim of the current research was to develop and evaluate a new questionnaire to examine fire-specific constructs relevant to fire misuse with both apprehended and unapprehended samples. Using latest comprehensive firesetting theory (i.e., the M-TTAF; Gannon et al., 2012), the theoretical constructs of inappropriate fire scripts and attitudes (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Ó Ciardha & Gannon,2012), and clinical practice, a large pool of questionnaire items was devised. Our predefined hypotheses are available via the Open Science Framework Repository (https://osf.io/p4v2j/). In Study 1, the large pool of items were presented to community participants alongside existing measures of fire-related constructs (i.e., the original Five Factor Fire Scales; Ó Ciardha et al., 2015Footnote 1; The Fire Interest Subscale; Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012). Using Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015) as a guide, we first attempted to replicate their findings in relation to self-reported deliberate firesetting that had not been officially recorded. Specifically, we predicted that approximately 10% of participants would self-report having set a deliberate fire. We predicted that these individuals would not differ to comparison UK community adults who do not self-report having set a deliberate fire on key demographic factors such as age, educational status, ethnicity, employment status, presence of a mental health diagnosis, learning disability, or criminal convictions. We aimed to then explore key features of the deliberate fires reported by unapprehended individuals as well as firesetting motivators and modus operandi and compare these findings to Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015). We also aimed to replicate the original Five Factor Fire Scale Structure reported by Ó Ciardha et al. (2015) in a mixed group of unapprehended community adults who self-report deliberate firesetting and community members who do not report such behavior. We expected to be able to discriminate these two groups of community individuals on four out of the five subscales (i.e., identification with fire, serious fire interest, fire safety awareness, firesetting normalization) in line with Ó Ciardha et al. (2015). Following this, we explored the emerging factor structure when combining the Five Factor Fire Scale with the Fire Interest subscale of the Fire Setting Scale (Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012), and the large pool of new questionnaire items that we had devised to see if these additional items elucidated new factors. We anticipated that any new factor structure would better discriminate community adults who self-report deliberate firesetting from other community members relative to the Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015). As an extension to this project, in Study 2, we validated the new measure developed in Study 1 with imprisoned individuals (with and without a firesetting history) as a well as community comparisons. We anticipated that any new firesetting questionnaire that emerged would discriminate individuals in prison who had set fires from their imprisoned counterparts who had not set fires and community comparisons. We also predicted that this discrimination would be superior to that exhibited by the pre-existing Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015).

Study 1

Method

Participants

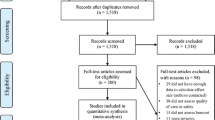

Individuals registered on the Prolific platform were invited to partake in this research entitled “Attitudes Towards Firesetting Study” if they were (a) 18 + years of age, (b) resident in the UK, and (c) had a 98%+ approval rate with a 200 + hit rate recorded on Prolific. This latter criterion was implemented to ensure that the participants we recruited had a record of extensive good conduct when engaging in online research. In total, 1,408 participants were recruited. However, six individuals answered the firesetting questions in such a manner that it was impossible to ascertain their firesetting status and so they were removed. This left 1,402 participants (M age = 40.8 years; 50.1% female; 91.2% White British). This study was ethically reviewed and approved by the University of Kent School of Psychology Ethics Committee [ID201815238945904987] and participants were reassured in the information and consent form that any disclosures of unapprehended firesetting would not be passed to the authorities.

Measures

We report internal consistency and reliability according to the following criteria (George & Mallery, 2003): ≥ 0.90 excellent, 0.89 to ≥ 0.80 good, 0.79 to ≥ 0.70 acceptable, and 0.69 to 0.60 questionable.

Demographic and Firesetting Disclosure Variables

A series of questions—stemming from the work of Gannon and Barrowcliffe (2012) and Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015)—were used to gain information on basic demographics, health/criminal background, and firesetting history of participants. Basic demographic variables collected included age, ethnicity, education level, and employment status. Health/criminal background variables collected were presence of a mental health diagnosis or learning disability, and any previous criminal convictions. Within the firesetting history section, in line with Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015), participants were asked to indicate whether they had deliberately set a fire or fires. They were provided with relevant examples of deliberate firesetting such as setting fires to annoy other people, to relieve boredom, to create excitement, for insurance purposes, due to peer pressure or to get rid of evidence. Participants were requested to exclude fires set accidentally, or set for organized events such as bonfires. In Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015) and other previous work using the firesetting history questions (e.g., Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2016; Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012) participants have been requested to exclude fires set before the age of 10 years (i.e., the age of criminal responsibility in the UK). In this study, we chose 14 years as the cut-off point for fire reporting to rule out self-reported childhood fire play. The majority of children in western cultures play with fire until they reach early adolescence (Kolko et al., 2001; Okulitch & Pinsonneault, 2002; Perrin-Wallqvist & Norlander, 2003) and these ‘play’ fires are likely to involve different etiological pathways to those associated with deliberate firesetting that persists into or occurs in adulthood. Participants who reported that they had set a deliberate fire were asked to answer additional questions (using a mostly forced choice response format) examining whether the participant had ever been arrested, convicted, or treated for their firesetting, number of fires set, presence of any co-perpetrators, age at first/last/only firesetting, factors preceding the firesetting (e.g., planning), modus operandi (e.g., use of accelerants), motivations and targets of the firesetting, community and perpetrator response to the firesetting (e.g., fire service attendance), and self-assessment of firesetting seriousness and factors that could have prevented the firesetting.

The Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015)

This scale combines items from the Fire Interest Rating Scale (Murphy & Clare, 1996)Footnote 2, Fire Attitude Scale (Muckley, 1997), and Identification with Fire Questionnaire (Gannon et al., 2011). Factor analysis (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) has indicated that five subscales can be empirically determined from this combination of measures: (a) identification with fire (“Fire is almost part of my personality”), (b) serious fire interest (“Watching a house burn down”), (c) perceived fire safety awareness (“I know a lot about how to prevent fires”), (d) everyday fire interest (“Watching a bonfire outdoors, like on bonfire night”), and (e) firesetting as normal (“Most people have set a few small fires just for fun”). Although a total score of four factors (omitting everyday fire interest) has been devised because everyday fire interest did not usefully discriminate firesetting from non-firesetting individuals (Gannon et al., 2013, Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015), we summed all five factors to produce a total score for this study. This total score reflects an individual’s overall fire interest, attitudes, and affiliation to fire with higher scores indicating problems in this area. Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al. (2015) has reported excellent (α = 0.90) measure reliability for the Five Factor Total Score with male prisoners. We found good measure reliability (α = 0.87).

The Fire Interest Subscale (Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012)

This is a 10-item scale developed to measure general fire interest. Examples of items include “I get excited thinking about fire” and “I like to watch and feel fire”. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (Not at all like me) to 7 (Very strongly like me). Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015) have reported excellent (α = 0.92) measure reliability for UK (Kent) community members. We also found excellent (α = 0.93) measure reliability.

The New Firesetting Items

Five members of the research team (TG, EA, HB, CÓC, and NT) created a shared document to develop, and agree upon, questionnaire items for testing. Several iterations of the document were developed until all five members of the research team agreed that ideas on content had been saturated. The research team used latest available firesetting theory (the M-TTAF; Gannon et al., 2012), fire scripts/cognitive theory (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Ó Ciardha & Gannon,2012), and clinical practice knowledge to devise 117 separate questionnaire items spanning 12 constructs (Fire is a good way of coping [9 items], Fire and self-harm [8 items], Fire as a powerful tool [18 items], Fire as soothing/comforting [11 items], Fire is controllable [11 items], Interest in fire paraphernalia [9 items], Fire interest/sensory stimulation [21 items], Fire-related social desirability [9 items], Fire as normal [6 items], Fire safety awareness/confidence [7 items], Fire destroys evidence [5 items], and Identification with fire [3 items]). Efforts were made to ensure that each item reflected the respondent’s own thoughts and feelings regarding fire rather than how they felt other individuals who have set fires might feel (e.g., “Watching even a small fire makes me happy”). Participants were instructed to show how much they agreed or disagreed with each statement using a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Eleven items were constructed to be reverse scored. A full list of the original questionnaire items is available on the OSF.

Impression Management

The Impression Management Scale (IM) of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR6; Paulhus 1991) is a 20-item self-report measure of intentional fake good responses (e.g., “I never swear”) that can be rated on either a 5- or 7-point scale. We selected a 5-point scale (1 = not true, 5 = very true) to keep the answer format broadly in line with the other measures used in this research. We updated the item “I never look at sexy books or magazines” to “I never look at sexy books, magazines, or websites” in keeping with modern sexual image use. Continuous rather than dichotomous scoring of the scale was used (Paulhus, 1994; Stöber, Dette, & Musch, 2002). The IM has well-established psychometric properties with offending populations (Gannon et al., 2013; Gannon et al., 2015; Lanyon & Carle, 2007; Paulhus, 1991) and we found good measure reliability (α = 0.84).

Procedure

Eligible participants completed the questionnaires online in August 2018 and were compensated financially for their time. Participants were presented first with the demographic and firesetting disclosure questions. Those who answered affirmatively to the firesetting screen were then presented with the further questions to explore key features of their firesetting incident(s). For the remainder of the online task, the questionnaire blocks were presented in a random order for each participant with item order randomized within each block. To identify participants who were not appropriately engaged with our study, we included regular attention checks (e.g., “Please select ‘No’ for this question”). For the key demographic variables and main questionnaire blocks, we included five attention checks. An additional two checks were included in the firesetting disclosure section since identifying as someone who has set a fire made the survey longer. Participants’ responses to these attention checks were calculated in line with our preregistration (where < 4/5 or < 6/7 indicated a failed attention check for non-firesetters and firesetters respectively). Only one person failed the attention check by scoring 5/7. This individual self-reported firesetting and correctly answered both attention check items in this section. They also took 952 s to complete the survey which was close to the average completion time (see below) and so in a departure from our preregistration were retained in the analysis. Average completion times for the survey were 1380.4s (SD = 701.4) for individuals who self-reported firesetting, and 1132.6s (SD = 499.3) for individuals who did not. No participant completed the study too quickly (i.e., in less than one quarter of the mean time taken by comparable firesetting or non-firesetting participants) or failed to complete any of the questionnaires and so all responses were retained in the analyses.

Analysis Plan

Data were analyzed in three key stages in line with our preregistered plan. Data for factor analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015), all other analyses were undertaken in SPSS for Windows 25.0 (IBM Corp., 2017).

Firesetting Prevalence and Features

The aim of this stage was to replicate Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015) using a 14-year minimum age for deliberate firesetting. In line with our pre-registration, we planned to recruit 1,400 community participants using the online crowdsourcing platform Prolific. This was based on a calculation of eight participants per questionnaire item (see Tabachnik & Fidell, 2007) and an estimated prevalence of 10% of individuals reporting having engaged in deliberate firesetting to ensure sufficient power (0.90) to detect an effect size of d = 0.30 with α = 0.05, when comparing unapprehended firesetting and non-firesetting participants. Here, we summed the number of participants who self-reported having set a deliberate fire not officially recorded and reported this as a percentage. We then used univariate comparisons (t test for continuous data, chi-squared for categorical data) to compare the demographic features of unapprehended individuals who self-reported firesetting with other community members who never reported setting a fire. Finally, we explored the key features of the deliberate fires (e.g., motive, modus operandi) using summary statistics.

2. Replication of The Five Factor Fire Scale Structure (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015)

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to directly examine the factor structure and item parameters proposed by Ó Ciardha et al. (2015) in a sample of community adults. We employed a loading criterion of 0.40 for items to be considered for retention, maximum likelihood model estimation, and Geomin oblique rotation to allow the factors to correlate. Comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) were computed and interpreted to evaluate strength of model fit and variations of factor solutions. Marsh et al., (2010) note that values > 0.90 and 0.95, regarding TLI and CFI respectively typically reflect acceptable and excellent fit to the data. For the RMSEA, values less than 0.05 and 0.08 reflect a close fit and a reasonable fit to the data, respectively. Marsh et al. (2004) cautioned about overgeneralizing these interpretive heuristics which can be questioned with respect to their practical significance; as such, we employ these metrics as a guide. Further, Schermelleh-Engel et al., (2003) identify that a χ2/df ratio between 2 and 3 represents good to acceptable fit, but they too caution that this procedure is heavily sample size dependent and is best considered a descriptive index. Modification indices from the Lagrange Multiplier test were used to identify other indicator-latent construct pathways not formally examined and/or that could be removed to improve model fit.

To examine how well the Five Factor Fire Scale structure discriminated between unapprehended individuals who had set fires and other community members, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses were conducted to generate Area under the Curve (AUC) statistics, representing the probability that a randomly selected individual from the firesetting group obtained a more problematic score than a randomly selected comparison individual. With AUC values of 0.50 representing chance level prediction, values of 0.56, 0.64, and 0.71 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Rice & Harris, 2005).

3. Development of A New Firesetting Questionnaire

The third stage of analysis aimed to explore the possible development of a new Firesetting Questionnaire, using a sample of community adults. Items from the Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015) and the Fire Interest Subscale (Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012), were combined with the 117 new firesetting items to investigate if these items further consolidated existing Five Factor Fire Scale factors or elucidated new factors. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on one randomly selected half of the sample to identify the strongest model fit to the obtained data and draw a relative comparison to the Five Factor Fire Scale factor item loadings obtained under our second stage of analysis and by Ó Ciardha et al. (2015). As above, we employed the maximum likelihood model estimation and Geomin oblique rotation to allow the factors to correlate. The final goal was to maximize parsimony and fit through scrutiny of the item content of the factor solution and three fit indices. CFI and RMSEA were computed and interpreted to evaluate strength of model fit and consistent with the results of EFA values loading below 0.40 were dropped (cf. preregistration). A CFA—employing the same model estimation parameters as the EFA—was then conducted on the second half of the data to test the initial EFA solution and refine questionnaire composition. The same fit criteria employed with the EFA were used to evaluate the replicability of the solution of overall CFA fit.

The remaining psychometric analyses were conducted on the aggregate sample to examine scale properties, and specifically, indexes of construct validity. Explorations of impression management (IM) were undertaken through a univariate comparison of non-firesetting and firesetting participants and a correlation between the firesetting questionnaire and IM. Residualized factor scores (i.e., controlling for IM score) were obtained for discriminatory analyses to control for IM effects. ROC curves were then plotted with associated AUC figures generated to examine factor and overall questionnaire discriminative ability. Again, Rice and Harris’ (2005) guidelines were used to interpret AUCs and p values and 95% CIs were calculated for comparison with the pre-existing Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015). To further compare the discriminative performance of the Firesetting Questionnaire relative to the original Five Factor Fire Scale, we opted to undertake a binary logistic regression analysis not specified in our original preregistration. This involved entering all Firesetting Questionnaire and Five Factor Fire Scale subscales simultaneously to examine which subscales were incrementally associated with binary self-reported firesetting.

Results

Firesetting Prevalence and Features

In line with our hypothesis, 137 participants (9.8%) reported having set a deliberate fire since the age of 14 years that they had not been arrested or convicted for. Two participants self-reported having interacted with a therapist as a result of their firesetting. Table 1 outlines the key demographic characteristics of individuals who reported having set a deliberate fire compared to those who reported never having set a deliberate fire. As hypothesized, there were no significant differences between the groups on ethnicity, educational level, or employment status. Both groups were majority White British, tended to hold post school qualifications, and were in some type of employment. Contrary to our hypotheses, those who self-reported firesetting were overwhelmingly male, and significantly younger than their non-firesetting counterparts. Individuals who had set a deliberate fire were also significantly more likely to have had a mental health or learning disability diagnosis at some point in their lives and were approximately four times more likely to have a prior criminal history.

Individuals who reported having set a deliberate fire had set, on average, 1.8 fires (range 1–5, SD = 1.3). Participants who had set multiple deliberate fires (n = 56) reported setting their first fire between the ages of 14Footnote 3 and 34 years (M = 15.9; SD = 3.8) and their most recent deliberate fire between the ages 14 and 57 years (M = 19.7; SD = 7.6). Participants who had set one deliberate fire (n = 81) reported setting this fire between the ages of 14 and 40 years (M = 16.9; SD = 4.4). The majority of individuals reported setting their fire(s) with another person or persons (76.7%; n = 105). Participants reported varied motivations for firesetting. The most commonly selected motives related to experimenting with fire (64.2%; n = 88), wanting to create excitement or loving fire (54%; n = 74), and being bored (32%; n = 44). Participants most commonly reported setting fire to outside rubbish bins (29.9%; n = 41), grass or shrubbery (25.5%; n = 35), inside rubbish bins or wastepaper baskets (16.8%; n = 23), clothing (11.7%; n = 16), or a house or building believed to be empty (7.3%; n = 10). The majority of participants reported using matches (59.8%; n = 82) or a lighter (54.7%; n = 75) to start their fires, while smaller proportions reported using aerosols (17.5%; n = 24), lighter fuel (16.1%; n = 22), and white or mineral spirits (16.1%; n = 22). Only a small proportion of participants rated their only fire or, for individuals who had set multiple fires, their most recent fire, as being serious through scoring > 4 out of 7 on a scale examining firesetting seriousness (6.6%; n = 9). Most participants stated that being more aware of the dangers of fire and having better fire safety knowledge would have prevented them from setting their fire(s) (46.7%; n = 64). However, just under a third of participants reported that nothing would have prevented them from setting their fire(s) (31.4%; n = 43).

Replication of the Five Factor Fire Scale Structure (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015)

CFA was conducted on the full community sample (N = 1402) to test a correlated five factor solution. The CFA without modification generated a relatively poor fit (CFI = 0.77; TLI = 0.75; RMSEA = 0.07; 95% CI. 0.066, 0.070), χ2 / df ratio = 17884.844/666 = 26.85. The CFI and TLI values were below the conventional 0.90 to 0.95 threshold although the RMSEA value was within the acceptable threshold. There was a large χ2 / df ratio indicating poor fit between the CFI model and the data. Table 2 presents the standardized CFA results with standardized item loading parameters (ranging between − 1.0 and + 1.0) presented. All items loaded on their respective factors with one exception (see Table 2) and were significant at p < .001. However, modification indices indicated a number of item cross loadings would be required to improve model fit.

Table 3 presents the AUC values for the Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015) factors and total scores in the discrimination of people with a self-reported history of firesetting versus those without. The Total score demonstrated large magnitude effects for accurately identifying people with a history of firesetting. Factor 5 (Firesetting as Normal) also demonstrated a large discriminatory effect. Factor 3 (Fire Safety) did not discriminate better than chance, and the remaining factors demonstrated small to moderate effects.

Development of a New Firesetting Questionnaire

EFA was used on one half of the community sample (N = 701) to identify the latent constructs underpinning firesetting for subscale development, identify potentially weaker psychometric items that did not load on a given factor, and to prune down the scale to a manageable length. This analysis suggested the retention of 90-items arranged into eight factors (see Table 4). These factors were labelled firesetting as normal (5 items), identification with fire (8 items), fire interest (21 items), fire safety (9 items), pathological fire interest (4 items), coping using fire (12 items), fire is a powerful messenger (21 items), and fascination with fire paraphernalia (10 items). Note that we removed one overlooked duplicate item from Factor 7 (i.e., “Setting a deliberate fire is a good way to tell people you need help”). The final model fit was strong (CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.87; RMSEA = 0.04; 95% CI. 0.039, 0.042), χ2 / df ratio = 7279.30/3395 = 2.14. Attempts to extend the solution beyond eight factors yielded diminished returns, specifically, factors extracted tended not to have any items loading highly and thus appeared to be pseudo factors. These factors improved model fit in theory but offered little additional information to the eight-factor solution.

CFA was conducted on the second half of the community sample (N = 701) to test a correlated eight factor solution. The CFA without modification generated an acceptable fit (CFI = 0.80; TLI = 0.80; RMSEA = 0.05; 95% CI. 0.049, 0.051), χ2 / df ratio = 10960.437/3976 = 2.76. Due to the lengthy nature of the scale, CFI and TLI values were below the conventional 0.90 to 0.95 threshold although RMSEA values were within the acceptable threshold, as well as a small χ2 / df ratio indicating close fit between the CFI model and the data. Table 4 presents the standardized CFA results with standardized item loading parameters (ranging between − 1.0 and + 1.0) presented. All loadings were significant at p < .001.

Convergent Validity and Internal Consistency of Test Item Content

Table 5 shows the inter-factor associations generated from the eight-factor solution for the EFA (top diagonal) and the CFA (lower diagonal), with Cronbach alpha values for the aggregate sample on the principal diagonal. Broadly, moderate in magnitude associations were found for the factors generated from the EFA, with the exceptions of Factors 4 (Fire Safety) and 5 (Pathological Fire Interest), which had small in magnitude associations with most factors. A similar pattern of associations were found among the factors generated from CFA, however, these tended to be moderate to large in magnitude and these were slightly higher than observed in the EFA. The Firesetting Questionnaire Total had excellent internal consistency (α = 0.96, MIC = 0.24), demonstrating a high level of interrelatedness of test item content in measuring the psychological dimensions of the firesetting construct. The internal consistency properties also extended to each of the eight factors, with moderate to high alpha values observed. Finally, the item total correlations ranged from a low of 0.20 to well over 0.50 (see Supplemental Table S1) indicating that each item is measuring the same overall construct as the scale as a whole.

Discrimination Ability

Although our univariate comparison did not illustrate any notable difference between the study groups regarding IM (see Table 1), there was a significant positive relationship between IM and the Firesetting Questionnaire Total, r = .23, n = 1402, p < .001. Because of this, residualized factor scores were obtained to control for IM in analyses examining discriminative abilityFootnote 5. Table 3 presents the AUC values for the Firesetting Questionnaire factor and total scores in the discrimination of individuals with a self-reported history of firesetting versus those without. Like the Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015), the Firesetting Questionnaire Total score demonstrated large magnitude effects for accurately identifying people with a history of firesetting. Factors 1 (Firesetting as Normal), and 6 (Coping using Fire) had large effects, while the remaining factors had small to moderate effects; all AUCs were significant. This discrimination performance was enhanced relative to that demonstrated by the Five Factor Fire Scale (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015; see Table 3). To further compare the discrimination performance of the Firesetting Questionnaire relative to the original Five Factor Fire Scale, Firesetting Questionnaire and Five Factor Fire Scale factors were entered simultaneously into the regression to examine which factors uniquely and incrementally predicted a self-reported history of firesetting whilst controlling for all other factors (see Table 6). Table 6 is arranged so that analogous Firesetting Questionnaire and Five Factor Fire Scale factors are paired for the first fire factors, while factor domains unique to the Firesetting Questionnaire (factors 6–8) are presented at the bottom of the table. Only the Firesetting Questionnaire factors significantly and uniquely predicted firesetting status. The relevant factors were factor 1 (firesetting as normal), factor 4 (fire safety), and factor 6 (coping using fire) which also had the strongest bivariate associations in the ROC analysis. Factor 2 (identification with fire) was inversely associated with firesetting status when all other factors were controlled.

Study 2

Method

Participants

A total of 141 participants were recruited from prison establishments and the community (49 imprisoned males holding a record of firesetting, 62 imprisoned males without a record of firesetting, 30 community male comparisons). To be eligible for the study, participants had to be male adults (i.e., ≥ 18 years) and to comprehend and speak English sufficiently to understand questionnaires. The imprisoned samples were recruited from one English prison establishment. Within the prison setting, participants experiencing active mania, psychosis, suicidal ideation, or at risk of hostage taking were excluded and no incentives were provided to partake in the study. Males holding a record of firesetting were selected from institutional file records indicating either a conviction for firesetting (i.e., arson) or prison firesetting activity (e.g., prison documented cell fires). Non-firesetting imprisoned males were selected to match imprisoned males with a documented firesetting history on age and wing as closely as possible. Each non-firesetting participant’s prison records were checked to ensure that they held no convictions or adjudications associated with deliberate firesetting. Although formal refusal rates were not possible to obtain from participating prisons, using our individual records we estimate that the participation rate was over 80%. Community participants were recruited from the same English county as the imprisoned participants using posters and flyers around a university campus and nearby City. These individuals were paid £10 for their participation and completed the measures under the same conditions as their imprisoned counterparts (i.e., items were read out loud to them in a private room). Analyses indicated demographic differences across the groups on almost every variable (see Table 7). Many of these differences were associated with the community sample who—relative to the prison samples—were highly educated, more likely to be in full time employment, and less likely to hold a clinical diagnosis.

Measures and Procedure

All participants were tested individually in a private room and measures were read aloud to participants to aid comprehension. Demographic information was collected first using a questionnaire developed by the authors. This recorded information about age, employment, ethnicity, formal education, relationship status, mental health diagnoses, and offense history. In addition, it recorded self-reported childhood and adult deliberate firesetting not captured by the offense history and examined whether the participant had ever used fire to intentionally harm another individual. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-second edition (WASI-II; Wechsler 2011) was also administered to gain an estimation of full-scale IQ (FSIQ) using the two-subtest form. Participants were then administered the new firesetting questionnaire produced from the EFA and CFA in Study 1. Following data collection, we noticed that the Factor 7 item “I imagine that setting a fire would be a good way of ending your own life” was mistakenly replaced with an item ruled out in the Study 1 factor analysis. Thus, the number of bona fide items administered to Study 2 participants was 89. Item order was not randomized.

Analysis Plan

We adhered to the analysis strategy outlined in our Study 2 preregistered plan using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) and SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., 2017) whilst also undertaking two additional analyses (correlations and MANCOVAs) to assess construct and discrimination ability respectively. First, we computed a correlation matrix of factor scores from the firesetting questionnaire as well as internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) to measure the interrelatedness of item content within each domain and the questionnaire as a whole. Here, correlation magnitudes were interpreted using Cohen’s (1988) conventions of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 to represent small, medium, and large effects respectively. MANCOVA was used to compare the three criterion groups whilst controlling for selected continuous variables that differentiated the participant groups in Table 7 and which could, theoretically, be linked to firesetting behavior (i.e., age, FSIQ, and firesetting history). To do this we conducted a MANCOVA with the firesetting questionnaire factors and total score as the dependent variables and age and FSIQ as covariates. At the second step, we repeated this analysis using lifetime firesetting history as a third covariate to control for variation in firesetting history density. We then conducted simple contrasts; comparing each of the comparison groups to the individuals who had set fires and used Cohen’s d conventions of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 to aid our interpretations of small, medium, and large effects respectively.

Our remaining analyses—as an extension to our pre-registered analysis plan—were conducted on the aggregate sample given that some individuals in the “comparison” groups disclosed a history of firesetting in childhood, adulthood, or both. ROC curves were plotted to examine how well the overall questionnaire and each of its subscales differentiated according to the binary firesetting criteria of: any childhood firesetting, any adult firesetting, convicted for firesetting, and firesetting with intent to harm. AUC statistics were computed and interpreted per the Rice and Harris (2005) guidelines as previously noted. Finally, regression analyses were conducted to examine which firesetting questionnaire factors incrementally predicted firesetting whilst controlling for the other questionnaire factors as well as age and FSIQ. Firesetting history—both child and adult—was an over-dispersed count variable, ranging from one or a few fires to thousands. As such, negative binomial regression was conducted to examine the unique associations of firesetting questionnaire factor scores for childhood and adult counts of firesetting with the age and IQ controls. Negative binomial regression generates regression coefficients (B and eB). These represent the amount of change predicted in the count variable (in log units), per one unit change in the predictor, controlling for other predictors. A further logistic regression was conducted examining the same model predictors for binary firesetting status (i.e., convicted firesetting versus membership in the combined comparison groups). The regression coefficients (B and eB) in logistic regression are interpreted as the percent increase in the odds of a binary outcome (e.g., firesetting group membership) per one-unit change in a given predictor, controlling for all other predictors.

Results

Table 8 displays the correlations between the firesetting questionnaire’s subscales as well as internal consistency figures. The majority of associations are significant and of a moderate to large effect size. Yet, these factor correlations were not so large as to create a problem with multicollinearity. The only exception was fire safety which held some non-significant associations. Cronbach’s alphas generally ranged from questionable (0.65; firesetting as normal) to excellent (0.95; fire interest and fire is a powerful messenger) with total alpha being very high (0.97). Pathological fire interest generated a very low alpha of 0.55 which may have been attributable to this factor having only four itemsFootnote 6.

Discriminative Ability

Table 9 presents the results of the MANCOVA with group simple contrasts whilst controlling for the covariates of age and FSIQ or age, FSIQ, and firesetting history. When controlling for age and FSIQ, those holding a record of firesetting scored higher than both the prison and community comparisons on identification with fire, coping using fire, and fire is a powerful messenger with effect sizes that were broadly moderate in magnitude (about 0.50 standard deviations). Individuals holding a record of firesetting also scored higher than the prison comparisons on fire interest and the firesetting questionnaire total when both age and FSIQ were controlled for. When an additional third covariate was controlled for—firesetting history— those holding a record of firesetting scored higher than prison comparisons with moderate effects (d = 0.40-0.51) on pathological fire interest, coping using fire, fire is a powerful messenger, and the firesetting questionnaire total. Although differences remained from community comparisons upward of a third of a standard deviation on the three domains previously found significant, these were no longer significant after adding firesetting history as a covariate.

Table 10 illustrates the bivariate associations between the firesetting questionnaire factor and total scores with various firesetting criteria through ROC and correlational analyses. The firesetting questionnaire total score was significantly associated with all of the firesetting criteria with moderate to large effects. In terms of the individual factors, coping using fire and fire is a powerful messenger each had significant moderate to large associations with each firesetting criterion variable (0.36 to 0.76). Particularly strong associations were apparent with the criterion variable of having intent to harm someone with firesetting (0.74 and 0.76 respectively). In contrast, the individual factor of fire safety was not associated with any of the firesetting criterion variables better than chance. The remaining factors were somewhere in between—identification with fire and fire interest had moderate associations with variables indicative of early onset and long duration of firesetting. Identification with fire also predicted adult firesetting and fire interest predicted having set a fire with the deliberate intent to harm someone. The individual factor of firesetting as normal had significant moderate associations with both childhood and adult firesetting (0.69 and 0.63 respectively) whilst fascination with fire paraphernalia had significant associations only with childhood firesetting (0.66).

Discussion

In this research, across two studies, we developed and validated a Firesetting Questionnaire to measure fire-related dynamic risk factors. In the first study, we presented community participants with pre-existing measures (i.e., the Fire Setting Scale; Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012 and the Five Factor Fire Scales; Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) alongside a set of new items designed to reflect latest available firesetting theory. Compared with the original Five Factor Fire Scales, the factor analyses of the Firesetting Questionnaire produced a stronger model fit suggesting that it represents a more adequate assessment of fire-specific constructs. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses showed that the Firesetting Questionnaire measures eight key constructs (i.e., firesetting as normal, identification with fire, fire interest, fire safety, pathological fire interest, coping using fire, fire is a powerful messenger, and fascination with fire paraphernalia) with acceptable convergent test item validity and acceptable to excellent internal consistencies (αs = 0.71 to 0.95; George & Mallery 2003). In terms of discriminative ability, the new Firesetting Questionnaire illustrated stronger performance than the Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) since only the Firesetting Questionnaire subscales of firesetting is normal, fire safety, and coping using fire uniquely predicted firesetting status when controlling for impression management. These findings broadly concur with our preregistered predictions. They suggest that both the Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) and the Firesetting Questionnaire have replicable factor structures. However, the findings regarding discriminative ability suggest that the Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) lack the item diversity required to adequately represent contemporary firesetting theory (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Gannon et al., 2022; Ó Ciardha & Gannon, 2012).

In the second study, we further explored the psychometric properties of the Firesetting Questionnaire using criterion groups drawn from a prison and the community. Generally, the new questionnaire exhibited good convergent validity and, with the exception of the firesetting as normal and pathological fire interest subscales, internal consistency was high (αs = 0.85 − 0.97). Men in prison who had a record of firesetting scored higher on various subscales relative to the criterion groups when controlling for age and FSIQ. When stricter measures were put in place, (i.e., controlling for firesetting history in addition), only the imprisoned men’s scores differed. In particular, imprisoned men who had a firesetting record scored higher on the pathological fire interest, coping using fire, and fire is a powerful messenger subscales in addition to the Firesetting Questionnaire total score. Since individuals in both the imprisoned and community groups disclosed some history of firesetting, ROC curves were plotted to assess the Firesetting Questionnaire’s association with firesetting criteria. The total score was moderately to strongly associated with the presence of childhood or adult firesetting, holding a firesetting conviction, and intending to harm someone when firesetting. In terms of individual subscales, coping using fire and fire as a powerful messenger showed the best associations with firesetting criteria and the fire safety subscale showed the poorest. Overall, the findings from Study 2 provide evidence to support the psychometric robustness of the Firesetting Questionnaire with an imprisoned sample. In fact, the subscales of coping using fire and fire is a powerful messenger—reflecting content not included in previous questionnaires—performed particularly well as discriminatory measures.

When examining the overall pattern of results across Studies 1 and 2, the internal validity of the overall Firesetting Questionnaire was consistently excellent (Study 1 α = 0.96, Study 2 α = 0.97) illustrating a high level of interrelatedness of overall test item content across both community and imprisoned samples of participants. The total score illustrated strong discrimination ability across both studies and was a robust predictor of firesetting in childhood and adulthood, any firesetting conviction, and intent to harm others with firesetting (Study 2). Taken together, these results suggest that the Firesetting Questionnaire as an overall measure can be used with both community and imprisoned samples and that this measure is likely to be useful for predicting firesetting behavior across the lifespan as well as firesetting characterized by intent to harm.

Across studies, there were four occasions when we deviated from our preregistration plan. On two occasions, we made minor alterations to our preregistration procedure since we felt these alterations made sense in the context of our findings (i.e., choosing to retain one outlier that did not impact the pattern of results and dropping EFA values loading < 0.40 for Study 1). On the other two occasions, we incorporated additional analyses to further explore construct and discriminative ability (Study 1 Binary regression, Study 2 Correlation and MANCOVA).

Firesetting Questionnaire Content

The factor structure of the Firesetting Questionnaire elucidated in Study 1 mirrored that of the existing Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) to some degree. Three of the Firesetting Questionnaire subscales (firesetting as normal, identification with fire, pathological fire interest) shared notable portions (4, 7, 4) of original item content from the Five Factor Fire Scales of firesetting as normal, identification with fire, and serious fire interest respectively (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015). Two of the Firesetting Questionnaire subscales (fire interest and fire safety) reflected the general concepts of the original subscales featured in the Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015) using generally new question content. The incremental validity analyses conducted in Study 1 indicated that the Firesetting Questionnaire versions of the firesetting as normal, identification with fire, and fire safety subscales held discriminative ability that was not demonstrated by the equivalent factors of the Five Factor Fire Scales (Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015).

Perhaps the most interesting outcomes, theoretically, related to the three new subscales (coping using fire, fire is a powerful messenger, and fascination with fire paraphernalia) elucidated by the Firesetting Questionnaire factor structure. The coping using fire subscale was comprised of 12 items reflecting an interest in fire misuse to cope with stress and improve affect. These items fit broadly with the theoretical construct of a fire coping script (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Gannon et al., 2012) in which fire is cognitively relied upon to cope with life events, problems, and associated negative affect (e.g., ‘I set fires to unwind’, ‘If I had a problem, setting a small fire would make me feel a lot better’). The fire is a powerful messenger subscale also fits broadly with the theoretical construct of an inappropriate fire script since it encapsulates cognitions around fire misuse being a powerful method of indicating distress, gaining attention, or sending a powerful message of revenge (e.g., ‘Fire is a great way to show your distress to others’, ‘Fire will get me attention’, ‘Setting a deliberate fire is a great way to get revenge’). This subscale appears to tap into two key scripts: the aggression-fire fusion script proposed by Gannon et al. (2012) and the fire is a powerful messenger script (Butler & Gannon, 2015). To our knowledge, both the coping using fire and fire is a powerful messenger subscales represent the first self-report measures developed to tap into the theoretical construct of inappropriate firesetting scripts proposed by Gannon and colleagues (Butler & Gannon, 2015; Gannon et al., 2012; Gannon et al., 2022).

The third new subscale to emerge examines fascination with fire paraphernalia (e.g., ‘I often find myself staring at a fire engine if I see one’). The emergence of this subscale suggests that fascination with fire and fire-related paraphernalia represent two distinct constructs that may require separate assessment both academically and clinically. Notably, previous measures have tended to combine these concepts (Murphy & Clare, 1996; Ó Ciardha, Barnoux et al., 2015).

When examining the performance of the Firesetting Questionnaire subscales across Studies 1 and 2, the data from our unapprehended sample suggest that viewing firesetting to be a relatively usual occurrence, perceived fire safety awareness, and a preference to use fire to cope emerged as key predictors of firesetting behavior. This suggests that individuals who have not been detected for their community firesetting behavior reside in neighborhoods in which fire misuse is prevalent, believe themselves to be knowledgeable about fire, and use fire to alleviate negative affect. Previous research examining unapprehended samples who have set deliberate fires has indicated that they are characterized by having family members who have set fires (Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2015, 2016) as well as antisocial attitudes and associates (Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2016). This suggests that social learning variables (Jackson et al. 1987) and attitudes supporting antisocial behavior (Gannon et al., 2012) may be important etiological factors in the sequelae of unapprehended firesetting. Given the unapprehended individuals who self-reported firesetting reported themselves to be proficient in fire safety, it may be that they have developed some level of proficiency at evading detection. Future research efforts might seek to examine expertise in this group (see Butler & Gannon, 2015, 2021) and in particular any methods used to evade detection.

By comparison, the data reported in Study 2 showed that holding an identification with fire, believing fire to be a powerful messenger, and coping using fire emerged as key associates of holding a firesetting conviction. This suggests that individuals who have been detected for their firesetting behavior view fire as a central aspect of their life and personal identity, use fire as a powerful method of indicating distress, gaining attention, or enacting revenge, and view fire as a way of alleviating negative affect. While using fire to cope appears to be a sentiment shared with individuals who remain unapprehended for their firesetting (Study 1), using fire as a means of grabbing attention is not. This latter feature may have led to the arrest of these individuals. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare fire-related factors across apprehended and unapprehended samples of individuals who have set fires. Further research is required to elucidate the fire-related similarities and differences across these groups.

Firesetting Prevalence and Features

In Study 1, a key aim was to replicate Barrowcliffe and Gannon’s (2015) work on unapprehended firesetting. As predicted, using a 14-year minimum age cut-off, we found that approximately 10% of UK resident community adults self-reported having set a deliberate fire that had not been officially recorded. This is roughly in line with previous work conducted in the UK (i.e., Gannon & Barrowcliffe, 2012) and lower than the 18% reported by Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2016). The current study holds the largest sample of UK community participants (i.e., 1,402) used to examine the prevalence of unapprehended firesetting to date using a conservative age cut off designed to exclude fire play. We found few demographic differences between the firesetting and non-firesetting groups which was generally in keeping with Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015). However, contrary to their study, we found that individuals who self-reported having set a deliberate fire were generally male, young, had received a mental health diagnosis, and were more likely to have a prior criminal history. Since just under half of our firesetting participants stated that having better fire safety knowledge would have prevented their fires, fire prevention efforts might be most successful if they are fire safety oriented and targeted towards youth mental health and justice services. Our examination of the features of the self-reported firesetting illustrated that the ages when these fires were set were broadly in line with the ages reported by Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015) and the majority of our sample (76.7%) set fires with other individuals. Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015, 2016) also reported that the majority of their self-reported fires were set in the company of others. Again, this supports the idea that antisocial associates represent a key factor in the firesetting self-reported by UK community participants. The firesetting group in our study, similarly to Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015), reported varied motivations for their fire misuse. The most commonly cited motives of experimenting with fire, wanting to create excitement or loving fire, and boredom all reflect the most popular motivators reported by Barrowcliffe and Gannon (2015, 2016). This replication suggests that these motives are reliable drivers underpinning unapprehended community firesetting. Items most commonly set fire to by our firesetting participants were rubbish bins, and grass or shrubbery (cf. Barrowcliffe & Gannon, 2015, 2016) and very few of our firesetting participants perceived their fires as having been serious. These targets and the appraisals of participants regarding seriousness suggest that their fires were generally lower level and so may not have attracted the attention of authorities in order to secure an arrest or caution. Nevertheless, ten participants disclosed that they had set fire to what they believed to be an unoccupied building suggesting that the questions we asked regarding unapprehended firesetting captured serious offending behavior.

Limitations

A key limitation associated with questionnaire development studies is that the initial factor structure described typically requires further replication. In our research, we did not attempt to replicate the Firesetting Questionnaire’s factor structure in Study 2 due to the size of our specialist imprisoned sample. However, in Study 1, we divided our large sample in two which enabled us the opportunity to replicate our initial exploratory factor solution and refine questionnaire composition via confirmatory factor analysis. Consequently, we can be reasonably confident that the factor structure of the Firesetting Questionnaire is replicable. Nevertheless, we invite researchers to replicate the factor structure described in this paper using a larger sample of both unapprehended and apprehended individuals who have set fires.

Finally, the questionnaire items initially presented to participants in Study 1 were extensive and encompassed items designed to tap into broad fire supportive attitudes (e.g. fire is controllable; Gannon et al., 2012; Ó Ciardha & Gannon,2012), fire-specific social desirability (e.g., ‘Lighting a fire or a couple of candles can make a room look nicer’), and further inappropriate firesetting scripts (e.g., fire destroys evidence). Interestingly, none of these concepts were clearly elucidated when items were factor analyzed. It is possible, that our choice of sample (i.e., generally noncriminal community individuals) when developing the questionnaire may have generated concepts more applicable to unapprehended rather than apprehended individuals who have set fires. However, if this is the case, the results of Study 2 suggest that the questionnaire holds convincing associations with fire convictions. Furthermore, many individuals convicted of a firesetting offence tend to self-report other unapprehended incidents of firesetting (see Gannon et al., 2015). Finally, some of the individuals in the study initially chosen as comparison groups due to their non-firesetting status self-reported some history of firesetting behavior. Taken together, these findings suggest that the questionnaire developed in Study 1 is likely to produce valid and reliable measurement across firesetting groups. Nevertheless, there remains an argument to examine measurement of concepts such as fire attitudes and scripts in greater depth for apprehended populations.

Clinical Implications

Following further validation, the Firesetting Questionnaire shows promise as a clinical tool for therapists working with both apprehended and non-apprehended individuals who have set deliberate fires. Since 10% of the population identify themselves as having set a deliberate fire, firesetting history might reasonably be assessed at general intake for both prisons and psychiatric hospitals. The Firesetting Questionnaire could then be used to examine the possible drivers of such behavior and to put in place firesetting management plans or treatment. Similarly, for those individuals in which firesetting is clearly a behavioral issue, the Firesetting Questionnaire might be used to examine the key treatment needs that require targeting in any planned intervention and to inform appropriate risk assessment.

Conclusion

This research developed and evaluated a new measure named the Firesetting Questionnaire to examine fire-specific constructs relevant to fire misuse using both apprehended and unapprehended samples. Our analyses suggest that this new measure holds better coverage of theoretically informed fire-specific dynamic risk factors relative to the most commonly used contemporary measure (Ó Ciardha et al., 2015). It also showed superior discriminative ability in relation to firesetting behavior and was associated with varying firesetting criteria including any lifetime firesetting and firesetting convictions. The results suggest that the Firesetting Questionnaire has the potential to be a useful clinical tool for highlighting fire-specific treatment needs to inform clinical formulation and associated risk management. It might also be used to assess change following treatment which would help professionals to establish convincing evidence of ‘what works’ to reduce deliberate firesetting behavior.

Notes

Referred to as Ó Ciardha et al. (2014) in the preregistration due to online publication first.

We modernized one item that asked participants to think about watching an ordinary coal or wood fire by including gas fire in addition.

This minimum age of 14 is a result of the fact that this was the lowest age participants could report for firesetting.

The Five Factor Fire Safety Scale has 6 items. The item ‘If you’ve got problems, a small fire can help sort them out’ did not replicate in this CFA.

Analyses conducted without residualized factor scores did not meaningfully differ from those reported here.

We are confident that the low alpha for pathological fire interest is due to the low number of items because if you increase the number of items from 4 to 20, with a mean inter-item correlation of 0.247, item covariance of 0.213, and mean item variance of 0.900, this boosts the alpha to 0.86 using Cronbach’s formula (an increase from 4 items to 10 items brings the alpha to 0.76). One item has a low correlation with the other items in this small sample, which further attenuates the alpha, but this is to be expected when cross validating to a new (especially smaller sample).

References

Barrowcliffe, E. R., & Gannon, T. A. (2015). The characteristics of un-apprehended firesetters living in the UK community. Psychology Crime and Law, 21(9), 836–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2015.1054385.

Barrowcliffe, E. R., & Gannon, T. A. (2016). Comparing the psychological characteristics of un-apprehended firesetters and non-firesetters living in the UK. Psychology Crime and Law, 22(4), 382–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2015.1111365.

Barrowcliffe, E. R., Tyler, N., & Gannon, T. A. (2022). Firesetting among 18–23 year old un-apprehended adults: a UK community study. Journal of Criminological Research Policy and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-06-2021-0026.

Butler, H., & Gannon, T. A. (2015). The scripts and expertise of firesetters: a preliminary conceptualization. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 20, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.12.011.

Butler, H., & Gannon, T. A. (2021). Do deliberate firesetters hold fire-related scripts and expertise? A quantitative investigation using fire service personnel as comparisons. Psychology Crime & Law, 27(4), 383–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1808978.

Campbell, R. (2021, September). Intentional structure fires.National Fire Protection Association. https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-tools/US-Fire-Problem/Intentional-fires

Collins, J., Barnoux, M., & Langdon, P. E. (2021). Adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism who deliberately set fires: a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 56, 101545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101545.

Fritzon, K., Doley, R., & Clark, F. (2013). What works in reducing arson-related offending. In L. A. Craig, L. Dixon, & T. A. Gannonred What works in offender rehabiliation: an evidence-based approach to assessment and treatment (pp. 255–270). Wiley-Blackwell.

Gannon, T. A., Alleyne, E., Butler, H., Danby, H., Kapoor, A., Lovell, T., & Ó Ciardha, C. (2015). Specialist group therapy for psychological factors associated with firesetting: evidence of a treatment effect from a non-randomized trial with male prisoners. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 73, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.007.

Gannon, T. A., & Barrowcliffe, E. (2012). Firesetting in the general population: the development and validation of the fire setting and fire proclivity scales. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 17(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532510X523203.

Gannon, T. A., Ó Ciardha, C., & Barnoux, M. (2011). The identification with fire questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript. Canterbury, UK: CORE-FP, School of Psychology, University of Kent.

Gannon, T. A., Ó Ciardha, C., Barnoux, M. F. L., Tyler, N, Mozova, K., & Alleyne, E. K. A. (2013). Male imprisoned firesetters have different characteristics than other imprisoned offenders and require specialist treatment. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 76(4), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2013.76.4.349.

Gannon, T. A., Ó Ciardha, C., Doley, R. M., & Alleyne, E. (2012). The multi-trajectory theory of adult firesetting (M-TTAF). Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.001.

Gannon, T. A., Tyler, N., Ó Ciardha, C., & Alleyne, E. (2022). Adult deliberate firesetting: theory, Assessment and Treatment. Wiley-Blackwell.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step by step: a simple guide and reference 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. IBM Corp.

Jackson, H. F., Glass, C., & Hope, S. (1987). A functional analysis of recidivistic arson. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1987.tb01345.x.

Johnston, K. L. (2022). Factors associated with un-apprehended deliberate fire setting in an Aotearoa New Zealand community sample. [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]

Kolko, D. J., Day, B. T., Bridge, J. A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2001). Two-year prediction of children’s firesetting in clinically referred and nonreferred samples. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(3), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00730.

Lanyon, R. I., & Carle, A. C. (2007). Internal and external validity of scores on the Balanced Inventory of Desirable responding and the Paulhus Deception Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67(5), 859–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164406299104.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indices and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11, 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2.

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Muthén, B., Asparouhov, T., Morin, A. J. S., Trautwein, U., & Nagengest, B. (2010). A new look at the big five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modelling. Psychological Assessment, 22, 471–491. https://doi.org/en10.1037/a0019227

Muckley, A. (1997). Firesetting: addressing offending behaviour. A resource and training manual. Redcar and Cleveland Psychological Service.

Murphy, G. H., & Clare, I. C. (1996). Analysis of motivation in people with mild learning disabilities (mental handicap) who set fires. Psychology Crime and Law, 2(3), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169608409774.

Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (2015). Mplus Version 7.4. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Ó Ciardha, C., Barnoux, M. F. L., Alleyne, E. K. A., Tyler, N., Mozova, K., & Gannon, T. A. (2015). Multiple factors in the assessment of firesetters’ fire interest and attitudes. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.111/lcrp.12065.

Ó Ciardha, C., & Gannon, T. A. (2012). The implicit theories of firesetters: a preliminary conceptualization. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.12.001.

Ó Ciardha, C., Tyler, N., & Gannon, T. A. (2015). A practical guide to assessing adult firesetters’ fire-specific treatment needs using the four factor fire scales. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 78(4), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2015.1061310.

Okulitch, J. S., & Pinsonneault, I. (2002). The interdisciplinary approach to juvenile firesetting: a dialogue. In D. Kolko (Ed.), Handbook on firesetting in children and youth (pp. 57–74). Academic Press.

Palmer, E. J., Caulfield, L. S., & Hollin, C. R. (2007). Interventions with arsonists and young fire setters: a survey of the national picture in England and Wales. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 12(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532505x85927.

Paulhus, D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). Academic Press.

Paulhus, D. L. (1994). Balanced inventory of Desirable responding: reference manual for BIDR Version 6. Unpublished manuscript. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia.

Perrin-Wallqvist, R., & Norlander, T. (2003). Firesetting and playing with fire during childhood and adolescence: interview studies of 18‐year‐old male draftees and 18 – 19‐year‐old female pupils. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 8(2), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532503322362933.

Rice, M. E., & Harris, G. T. (2005). Comparing effect sizes in follow-up studies: ROC Area, Cohen’s d, and r. Law and Human Behavior, 29(5), 615–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-005-6832-7.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Test of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research - Online, 8(2), 23–74. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.509.4258&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Stöber, J., Dette, D. E., & Musch, J. (2002). Comparing continuous and dichotomous scoring of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable responding. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78(2), 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7802_10.