Abstract

The present article deals with potassium magnesium borate glass activated with copper that was prepared by a melting quenching technique to study the feasibility of this glass as a radiation dosimeter. The prepared glasses were characterized through X-ray diffraction and FTIR spectroscopy and some of the glasses optical and physical parameters have been interpreted. The thermoluminescence properties of the prepared samples were studied, and the results revealed that the potassium magnesium borate doped with 0.07 wt% with copper has the highest thermoluminescent response. The glow curve of potassium magnesium borate doped with 0.07 wt% of copper has seven overlapping peaks with maximum temperatures of 383.09, 400.71, 413.26, 426.59, 445.98, 476.57 and 534.04 K, and the TL-response is linear from 0.11 to 165 Gy. From the present study, the potassium magnesium borate doped with 0.07 mol% from copper may be applicable for measuring the radiation dose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nuclear and radiation technology has become one of the most used technologies in many fields, especially in medicine and radiation therapy, where precise dose measurement is needed. Currently, there are several types of radiation detectors available and the thermoluminescent dosimeter is the most important of them [1].

There is a wide range of TL materials in use, and the glassy system is among them. It is particularly appealing for radiation processing applications [2,3,4,5]. In recent years, the study of radiation-induced defect centers in glasses has been beneficial in evaluating the quality of glasses for radiation dosimetry applications.

One of the essential glass-forming materials is boron oxide. Because of its high transparency, low cost, low melting point, high sensitivity, great thermal stability as compared to other TL materials, as it can be present with two groups, tetragonal BO4 and trigonal BO3 in the glass sample, the network improves the ability to modify its coordination state from boroxol rings to triangles and tetrahedral BO4 coordination's appearing short-range structure of triangles BO3 and tetrahedral BO4 groups [6,7,8,9].

Several attempts to enhance the dosimetric characteristics of borate glass have been performed [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Several alkali/alkaline metals have been used as modifiers to borate dosimeters over the years [16,17,18].

Copper is one of the transition metal oxides (TMO) that can exhibit in different oxidation states Cu2+, Cu+, and Cu0, which can coexist. The other states of copper ions in the glass matrix led to the intense greenish and bluish color of the glass samples.

Copper is one of the best activators used to enhance the luminescence properties of borate dosimeters as copper can form luminescence centers, which are essential for increasing phosphor strength [18] also, copper has non-hygroscopic nature which increases the chemical stability of borate dosimeters [19].

Upon irradiation, numerous typical defects of borate could appear including boron E-center, non-bridging oxygen NBO’s hole centers,which may be clarified as hole center HC, hole trapped on a single NBO, and HC2 hole trapped on two NBO hole center. [20]

The main aim of the present study is to investigate the physical properties of potassium magnesium borate glass doped with copper, such as density, polaron radius, molar volume, average molecular weight, ion concentration, and TL properties, to use it as a high-dose radiation dosimeter.

2 Methodology

2.1 Glass preparation

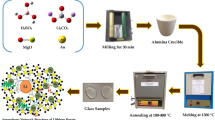

The glass composition (70 − x) B2O3–10 K2O–20MgO–xCuO, x = (0.02, 0.07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 1.2 mol%), was prepared by the melt-quench technique. B2O3 was obtained from H3BO3, K2O was obtained from potassium carbonates. MgO and CuO were added as magnesium and copper from each metal oxide (99.99% purity, Alfa). The melt-quench process was used to prepare the mixtures in a porcelain crucible at 1150–1200 °C for 2 h.

2.2 Detailed measuring techniques and calculations for some physical parameter

The Shimadzu X-ray diffractometer was used to assess the condition of the produced glasses within a 2θ angle range of 5° to 60° at 40 kV and 30 mA. Cu Kα radiation and a scan rate of 6° per minute were used to collect data, as well as an X-ray tube. A Bruker's VERTEX 70 FTIR spectrometer was utilized to investigate the spectra of the produced samples at room temperature in the range 4000–400 cm−1, and the absorption spectra of the glasses were recorded. The density (D), molar volume (Vm), oxygen packing density (OPD), the ionic concentrations of the glass samples (N), Internuclear distance (ri) and polaron of each glass sample were calculated [21, 22].

The density was calculated according to the formula: ρ = wa/wa − wb × ρo, where wa is the weight of the glass sample measured in air, wb is the weight when the glass is immersed in liquid, and ρo is the density of azylene. The molar volume (Vm) was calculated according to the formula Vm = M/ρ, where M is the total molecular weight of the multi-component sample. The optical UV–visible absorbance spectra were measured within the UV–visible range (200–1100 nm) using a recording double-beam spectrophotometer (Type JASCO Corp, v-570, Rel-100 Japan) by finely polished glass system.

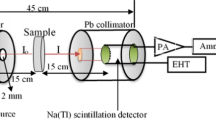

The Lexsyg Smart TL/OSL luminescent available at the Nuclear Radiation Measurements lab in Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University was used to measure the glow curve and other TLD—data for the study samples. Lex Studio 2.0 operating software, which runs on a personal computer linked to the reader, controls the reader. The reader is also linked to the nitrogen supply for cooling reasons.

The study samples were irradiated with beta- particles using a beta source of 90S/90Y, at a dose rate of 110 mGy/s built into the TLD- reader. The result glow curves after being measured were deconvoluted using El-Kinawy TL—software [23].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Glass characterization

3.1.1 X-ray diffraction (XRD)

As shown in Fig. 1, XRD was carried out on the selected prepared glass sample. It has revealed that peaks of diffraction did not appear. In contrast, only broad bands appeared at around 2θ = 25° for select samples (0, 1.2 mol% CuO), approving the non-crystalline nature of the produced glass.

3.1.2 FTIR spectroscopy

The FTIR analysis of the analyzed samples was optimized to obtain information on the structural units. In this study, it was observed that the vibrational modes of the borate network are mainly active in three infrared spectral regions from 1200 to 1500 cm−1 (B–O stretching of trigonal BO3 units), from 800 to 1200 cm−1 (B–O stretching of tetrahedral BO4 units), and from 600 to 800 cm−1 (bending vibrations of various borate segments) [7, 24, 25]. As shown in Fig. 2. The undoped glass reveals several absorption bands extending from the beginning of the measurements at 400 up to 2000 cm−1. The main prominent and characteristic absorption bands usually observed in these three spectral regions are observed at 450, 530, 610, 830, 1070, 1110, 1240, 1380, and 1460 cm−1. The spectral bands in the region of 420–470 cm−1 are assigned to specific vibrations of Na–O bonds [26]. The band around 530 cm−1 in the region of 500–550 cm−1 is assigned to the borate deformation modes [27]. The band located at 700 cm−1 is due to B–O–B bending in trigonal BO3 units [28]. The absorption in the region 650–700 cm−1 is attributed to the bending vibrations of B–O–B in BO3 [26]. The spectral band in the region of 780–1100 cm−1 is due to the B–O symmetric stretching of tetrahedral BO4 units and vibrations of diborates bridging to pentaborate groups [29]. The spectral band in the region of 1200–1300 cm−1 is due to the B–O bond stretching vibrations and B–O bridging between B3O6 and BO3 triangles [30]. The band at 1100 cm−1 may be due to the stretching vibration of B–O bonds in BO4 units from tri, tetra, and pentaborate groups [28]. The spectral band in the region 1200–1300 is attributed to anti-symmetrical stretching vibrations with three NBOs of B–O–B groups [31]. Figure 2 also reveals the FT-IR of samples containing progressive addition of CuO. The careful inspection of all the spectral curves before and after doping marked a slight change in the intensity of bands. Some bands of BO4 groups shifted to a higher wavenumber, while the BO3 groups were shifted to a lower wavenumber which is in agreement with other research [7, 32, 33]. At the same time, the absorption band becomes broader and accompanied by a shift to a longer wavelength. This may be due to the introduction of CuO transforming some of the BO3 triangles to BO4 tetrahedra or vice versa. So, authors used deconvolution method to estimate the fraction of N4 of BO4 units in the borate network using the Peak Fit program (version 4.12). As shown in Fig. 3a and b and Table 1, for 0 and 1.2 mol% CuO glass sample, they stem from asymmetric stretching vibrational modes of orthoborate, pyroborate, and triangle BO3 group, respectively. The deconvoluted data of this band also helped to calculate the relative areas of the absorption peaks related to BO4 and BO3 groups (N4 and N3, respectively) and the fraction of the four coordinated boron atoms (N4) from the infrared spectra. Besides, the relative area of the deconvoluted bands indicates the variation in N4 in the structure [28, 34]. The tetrahedrally coordinated boron atoms fraction N4, as well as N3, can be calculated using the following formulas:

where N3 and N4 represent the area of peaks corresponding to BO3 and BO4 groups. Figure 4 shows the relation between copper oxide concentration and N4 content, indicating that N4 in a glass is reduced as the copper oxide level rises. On the contrary, N3 increases with increasing the copper oxide content. It can be shown that increasing the copper oxide level significantly influences increasing NBOs. The negative charge on NBOs makes it easier for electrons to be excited at longer wavelengths [7, 35, 36]. The above arguments suggest that the N4 ratio is the most prominent factor in increasing density and decreasing molar volume.

3.2 Density and other parameters

The addition of copper oxide to the glass network may cause some changes in the structure. These changes include rearrangement of the atoms, coordination numbers of the constituents, and variations in the geometrical configuration of the glass that are directly affected by the density. The investigated glass density was changed with the increment in the content of CuO at the expense of the B2O3 content, as shown in Fig. 5. The increase in density might be due to the substitution of lower atomic mass (B2O3 = 69.62) with higher atomic mass (CuO = 79.547). It is possible that most of the Cu ions enter the glass samples network as a modifier, which consolidates their structure and raises their density [7, 28].

In the current work, the molar volume and the density display opposite behavior, which is the normal trend [28, 37].

The following relationship can expect the ion concentration of Cu as given in Table 2:

According to the current study, Cu ion concentration values increase with increasing the Cu content. This increase is associated with reductions in the molar volume.

The relationship (4) will be used to calculate the interionic distance (ri) between two Cu ions

It was observed that as the concentration of CuO increased, the values of ri reduced, and this reduction was associated with a decrease in the molar volume.

3.2.1 Optical absorption spectroscopy

Figure 6 shows the UV–Visible optical absorption spectra of the investigated polished glassy samples at room temperature against the 300–1100 nm wavelength. The obtained results of undoped copper are neutral, while the samples doped with copper oxide have a bluish-green color with cumulative copper oxide, then the color changes to dark green. The green color is an indication that the copper has a Cu2+ divalent oxidation state. The glass samples have a broad visible band around 780 nm [38], which may be recognized as a d–d transition due to Cu2+(d9) ions in the octahedral field, owing to the 2B1g → 2B2g octahedral transition of Cu2 + ions [28]. The peak position is shifted toward higher wavelengths due to the ligand field around the Cu2+ ion. An electronic hole in the degenerated orbital disturbs the Cu2+ ions, causing the tetragonal distortion. The Eg optical bandgap values with the concentration of Cu2+ are listed in Table 2.

3.2.2 Some physical parameters

Optical bandgap energy (Eopt), for indirect transitions, is sensitive to bonding between atoms. Energy gap calculations match those of Davis and Mott [39]. (αhν)1/2 = B(hν − Eg), where hν is the incident photon energy, B is the band tailing parameter constant, and Eg is the optical bandgap energy. The optical band gap value can be detected in Fig. 7, and the values are listed in Table 2. It was noticed that the optical bandgap energy values were reduced by increasing the concentration of Cu2+ at the expense of B2O3. This reduction allowed a decrease in the width of the localized states (γ) values and the average binding energy (cohesive energy). These are the main factors in increasing the number of free electrons less tightly linked to the nuclear charge. Free electrons can move from the valence band to the conduction band, decreasing the Eg optical bandgap energy. The refractive index (n) was valued from the values of Eopt using the following relation proposed by glass scientists [40, 41]:\(\frac{{n}^{2}-1}{{n}^{2}+2}=1-\sqrt{\frac{{E}_{\text{g}}}{20}}\). The refractive index values increased with cumulative Cu2+ concentration; this caused a rise in the amount of BO3 and NBO, while BO4 decreased. This observation can be attributed to the conversation of BO4 into BO3 and NBO. The optical electronegativity (χ) has been valued by, \(\chi =0.2688{E}_{\mathrm{g}}\), where \({E}_{\mathrm{g}}\) is the bandgap. Thus, the electronegativity (χ) values were reduced with cumulative Cu2+ concentration. The optical basicity was \(\wedge =-0.5\upchi +1.7\), so the electronegativity (χ) values were reduced through cumulative Cu2+ concentration. The electron polarizability has been valued by \(\propto^\circ =-0.9\upchi +3.5.\) The change in the value of the electronic polarizability by cumulative Cu2+ concentration in the glasses may tend to break down borate bonds to create non-bridging oxygen atoms [42].

The molar refraction Rm is styled by the following Lorentz–Lorenz equation [43]:

Rm is the molar refraction, Eg is the energy bandgap, and Vm is the molar volume.

The findings showed that adding CuO reduced the optical basicity, optical bandgap, and electronegativity while increasing the refractive index. The metallization criterion has been estimated as \(M=1-{{R}_{\mathrm{m}}}/{{V}{\text{m}}}\). Table 2 revealed that the metallization value decreased by adding Cu2+[21, 36].

3.2.3 Thermoluminescent properties

The TL-intensity and glow curve of potassium magnesium borate doped with 0, 0.02, 0.07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.7, 1, and 1.2 mol% concentrations of copper after being exposed to β-dose 55 Gy have been investigated, and the results are displayed in Fig. 8a and b.

This result showed that the doping of potassium magnesium borate with copper significantly increased the TL-intensity compared to undoped potassium magnesium borate. The resulted increase in the TL-intensity is dependent on the mol % of copper.

On the other side, the potassium magnesium borate doped with different mol% of copper has the same glow curve structure with one broad peak in the same position at ≈ 383.7 K, but the area under the glow curve has changed with the change in the mol% of copper.

The presence of one broad peak in the glow curve of potassium magnesium borate doped with copper means that this peak may be composed of more than one glow peak overlapping with each other. Each peak is specific to one trap in the crystal lattice. The positions of these traps in the crystal lattice of prepared glass are very close to each other. So, when the prepared glass was heated during reading, these peaks overlapped and appeared as one peak.

The highest TL-intensity was found in potassium magnesium borate doped with 0.07 mol% of copper. As a result, this specific concentration will be mainly discussed in the following section.

3.2.4 Kinetic parameters

Calculating the kinetic parameters of the electron traps inside the material is necessary to understand its behavior in recording the electrical charges and its ability to maintain this charge. However, to do this, the number of peaks that make up the curve should first be determined; if the glow curve has overlapping peaks, they must be separated first.

3.2.4.1 T m–T stop method

The Tm–Tstop technique [44] was used to determine the predicted number of the glow peaks in the glow curve of potassium magnesium borate doped with 0.07 mol% of copper. For this purpose, we performed the following:

-

The samples were irradiated at a dose of 132 Gy of beta particles.

-

The glow curve was recorded immediately after irradiation from room temperature to a temperature called Tstop (stopping temperature) at a linear heating rate of 5 K/s.

-

The samples were cooled to room temperature and reheated to record the whole glow curve up to 723 K with the same linear heating rate.

-

The temperature corresponding to the first maximum intensity in obtained glow curve (Tm) was determined.

-

The process of heating to a Tstop and cooling to room temperature, and then reheating to record the whole glow curve was repeated for different values of Tstop ranging from 328 to 648 K, with an increment of 5 K.

-

The corresponding Tstop and Tm were determined at each heating cycle, and a graph between various values of Tm against Tstop was obtained. The results are shown in Fig. 9.

From Fig. 9, the relation between Tm and Tstop appeared like a staircase structure where the relation began straight line; then a plateau occurred (flat region), after that, the relation retrained as a straight line, then the plateau region appeared again. The number and location of the plateau regions represent the number and locations of the glow peaks that make up the glow curve. So, the glow curve of potassium magnesium borate doped with copper 0.07 mol% has seven expected peaks at 383.09, 400.71, 413.26, 426.59, 445.98, 476.57, and 534.04 K.

Based on the expected number of glow peaks, the Glow Curve Deconvolution (GCD) was performed using El-Kinawy TL software [23], which determined the activation energy, frequency factor, and kinetic order for each peak after deconvolution. The quality of GCD fit between theoretical and experimental results has been tested with the Figure of Merit (FOM) [45, 46], as seen in Table 3 and Fig. 10. As shown in Table 3, the FOM value states the goodness of fit, where the values FOM less than 2.5% refer to a good fit [46].

3.2.5 Linearity and dose response

To establish the possibility of any material being used as a measure of radiation dose, it is needed to know the sort of connection between the radiation portion and the reaction of this material to radiation portion. It is favored that this relationship be linear.

The glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% was exposed to various doses of β-particles from 0.11 to 165 Gy. After that, the TL-response of the irradiated glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% samples was recorded, and the obtained glow curves corresponding to each dose were deconvoluted by El-Kinawy TL-software [23].

The shape and position of the peaks for the glow curve of the glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% did not change with the variation in the radiation dose as seen in Fig. 11, except the area under the glow curve and the corresponding TL-intensity increased with increasing the β-particle doses. This may be due to defects caused by β-particles plus the different types of defects already in the glass before irradiation, which causes an increase in the luminescence intensity [47].

Furthermore, increasing β-dose also induces additional luminescence centers. this may be due to the formation of some defects such as, non-bridging boron oxygen hole centers (NBOHC) / boron electron centers (BEC), and boron oxygen hole centers (BOHC).

The total area under the glow curve of the glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% was plotted as a function of β-doses. The obtained relation was fitted as a linear fit with the expression (Y = 5.13 + 0.92x), and the regression square fitting value equalled 0.998. These findings revealed that the glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% has a linear response from 0.11 up to 165 Gy from β-particle as seen in Fig. 12. The area under each peak after deconvolution of the glow curve was also calculated as a function of beta dose. The results showed that the seven peaks had a linear relationship with the β doses in the range of 0.88 up to 165 Gy and the results are presented in Fig. 13.

3.2.6 Reproducibility

It is necessary to verify the studied sample repeatability to be used as dosimeters to determine their accuracy. The ability to keep the TL response following the repeated use of the same dosimeter at the same applied dosage is referred to as "reproducibility". If the coefficient difference between readings after five to ten cycles is less than 5%, the dosimeter is regarded as having a high repeatability. [48, 49]. Thus, the TL-response of a sample from the glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% was studied after six cycles of irradiation at 0.22 Gy from β-particles and the results showed that the coefficient difference is 2.21% as shown in Fig. 14. This result showed that the glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% has a good reproducibility.

3.2.7 Sensitivity

One of the essential features that distinguish a dosimeter is its sensitivity. The sensitivity of the dosimeter could be assessed using Eq. (5) [49].

Hence, the sensitivity of the prepared glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% was calculated using Eq. (6) for dose range from 0.11 up to 165 Gy, and the results are shown in Fig. 15. It could be observed from this result that the sensitivity was decreased as the applied dose increased, where the average sensitivity overall studied dose range was 3309.49 ± 20%.

In addition, the relative sensitivity of the dosimeter could be assessed by comparing the intensity of the studied samples after being exposed to a certain dose with that obtained from a reference dosimeter (LiF, TLD-100) after being exposed to the same dose [49, 50]. Thus, samples from the glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% and TLD-100 were irradiated at 11 Gy, then the TL-intensity was recorded. The results revealed that TLD-100 has a relative sensitivity of 128.5 times as compared to that of a prepared glass system doped with 0.07 mol% copper (Fig. 15).

3.2.8 Fading

It is critical to understand the degree of electrical charge stabilization within the traps in the dosimeter over time [44]. So, a glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% sample was irradiated at 11 Gy from β-particle and stored in the dark at room temperature for an interval time. The results revealed that the residual TL-intensity was 10% after 72 h from the first reading and it remained constant over the remaining studied period of 696 h, as seen in Fig. 16.

The glow peaks at 383.09, 400.71, and 413.26 K disappeared after 72 h from irradiation which explains the quick fading in the first 72 h, hence these peaks are considered lower temperature peaks, however the glow peaks at 426.59, 445.98, 476.57 and 534.04 K remain constant overall the study period. Thus, it is recommended that when using the prepared glass pre-annealing should be performed before reading to temperature 415 K.

4 Conclusions

Based on the results, it can be concluded that:

-

The potassium magnesium borate doped with copper was prepared by a melting quenching technique to study the thermoluminescent behavior after β-particle exposure. According to the results, FTIR and N4 values established the occurrence of BO3 and BO4 groups in the glass network and the addition of CuO until the maximum concentration is reached (1.2 mol%) has no significant effect on the primary distinctive borate groups in the study, but slight changes in the intensities or places of some of the IR bands are identified.

-

The density of the glass system showed an increment in the content of CuO increases and molar volume decreases.

-

IR spectra reflect characteristic absorption bands due to specific borate network

-

The glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% has the highest TL-response, and its glow curve has seven overlapped peaks at 383.09, 400.71, 413.26, 426.59, 445.98, 476.57 and 534.04 K. The TL-response is linear from 0.11 up to 165 Gy. The coefficient difference for KMB: Cu 0.07 mol% is 3.37% after six irradiation and reading cycles.

-

The glass system doped with copper 0.07 mol% fades quickly in the first three days, then they remain stable. The calculated activation energies for seven peaks are 0.80, 0.90, 1, 1.01, 1.15, 1.20 and 1.30.

-

The potassium magnesium borate doped with 0.07 mol% copper found in the present work might be used to measure radiation dosage.

Data availability

My manuscript and associated personal data will be shared with Research Square for the delivery of the author dashboard.

References

M. Środa, S. Świontek, W. Gieszczyk, P. Bilski, The effect of CeO2 on the thermal stability, structure and thermoluminescence and optically stimulated luminescence properties of barium borate glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 517, 61–69 (2019)

N. Abdou, M. Farag, W. Abd-Allah, Thermoluminescent properties of nano-magnesium phosphate ceramic for radiation dosimetry. Eur Phys J Plus 135(3), 317 (2020)

A. El-Kheshen, C. Woda, M. Discher, N. El-Faramawy, Investigation of phosphate glass doped lanthanum as beta dosimeter. J. Lumin. 200, 254–259 (2018)

H.F. El-Nashar, M. El-Kinawy, N. El-Faramawy, Investigations of the kinetic energy parameters of irradiated (La)-doped phosphate glass. Luminescence 35(1), 107–113 (2020)

H.A. Alazab, N. Abdou, H. Saudi, W. Abd-Allah, Thermoluminescence properties of bioglass for radiation dosimetry. SILICON (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-021-01364-1

R. Kaur, V. Bhatia, D. Kumar, S. Rao, S.P. Singh, A. Kumar, Physical, structural, optical and thermoluminescence behavior of Dy2O3 doped sodium magnesium borosilicate glasses. Results Phys 12, 827–839 (2019)

W. Abd-Allah, E. Nabhan, Effect of CoO and gamma irradiation on the infrared absorption spectra of lithium borate glasses. SILICON 10(1), 49–57 (2018)

S. Hashim, Y. Alajerami, A. Ramli, S. Ghoshal, M. Saleh, A.A. Kadir, M. Saripan, K. Alzimami, D. Bradley, M. Mhareb, Thermoluminescence dosimetry properties and kinetic parameters of lithium potassium borate glass co-doped with titanium and magnesium oxides. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 91, 126–130 (2014)

B. Mohammed, M. Jaafar, H. Wagiran, Thermoluminescence dosimetry properties and kinetic parameters of zinc borate silica glass doped with Cu2O and co-doped with SnO2. J. Lumin. 204, 375–381 (2018)

N. El-Faramawy, S. El-Kameesy, A. Abd El-Hafez, M. Hussein, G. Metwally, Study of thermal treatment and kinetic parameters of prepared Li2B4O7: Cu Thermoluminescence dosimeter. Egypt. J. Sol 23, 103–111 (2000)

W. Ayta, V. Silva, N. Dantas, Thermoluminescent properties of a Li2O–B2O3–Al2O3 glass system doped with CaF2 and Mn. J. Lumin. 130(6), 1032–1035 (2010)

R. Nattudurai, A.K. Raman, C.B. Palan, S.K. Omanwar, Thermoluminescence characteristics of biological tissue equivalent single crystal: europium doped lithium tetraborate for dosimetry applications. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 29(17), 14427–14434 (2018)

N. El-Faramawy, A. El-Naggar, C. Woda, M. El-Kinawy, Dosimetric properties of lithium borate glass doped with dysprosium. Luminescence 36(1), 210–214 (2021)

N. El-Faramawy, A. El-Naggar, C. Woda, M. El-Kinawy, Investigation of TL dosimetric parameters of lithium borate glass doped with dysprosium. Opt. Mater. 113, 110672 (2021)

A. Saidu, H. Wagiran, M. Saeed, Y. Alajerami, A. Kadir, Effect of co-doping of sodium on the thermoluminescence dosimetry properties of copper-doped zinc lithium borate glass system. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 118, 375–381 (2016)

S. Rojas, K. Yukimitu, A. De Camargo, L. Nunes, A. Hernandes, Undoped and calcium doped borate glass system for thermoluminescent dosimeter. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 352(32–35), 3608–3612 (2006)

N.A. Salleh, A.R. Tamuri, M.A. Saeed, Effect of strontium concentration on thermoluminescence glow curve of copper doped lithium magnesium borate glass. Malaysian J. Fund. Appl. Sci. 13(3), 275–278 (2017)

Y. Alajerami, S. Hashim, S. Ghoshal, D. Bradley, M. Mhareb, M. Saleh, Copper doped borate dosimeters revisited. J. Lumin. 155, 141–148 (2014)

H. Aboud, H. Wagiran, R. Hussin, H. Ali, Y. Alajerami, M. Saeed, Thermoluminescence properties of the Cu-doped lithium potassium borate glass. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 90, 35–39 (2014)

I.A. Shkrob, B.M. Tadjikov, A.D. Trifunac, Magnetic resonance studies on radiation-induced point defects in mixed oxide glasses. I. Spin centers in B2O3 and alkali borate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 262(1–3), 6–34 (2000)

H. Saudi, W. Abd-Allah, K.S. Shaaban, Investigation of gamma and neutron shielding parameters for borosilicate glasses doped europium oxide for the immobilization of radioactive waste. J. Mater. Sci.. 31(9), 6963–6976 (2020)

K.S. Shaaban, W. Abd-Allah, Y. Saddeek, Gamma rays interactions with CdO-doped lead silicate glasses. Opt. Quant. Electron. 52(1), 1–17 (2020)

M. El-Kinawy, H.F. El-Nashar, N. El-Faramawy, New designed software to deconvolute the thermoluminescence glow-curves. SN Applied Sciences 1(8), 1–7 (2019)

S. Marzouk, N. Elalaily, F. Ezz-Eldin, W. Abd-Allah, Optical absorption of gamma-irradiated lithium-borate glasses doped with different transition metal oxides. Physica B 382(1–2), 340–351 (2006)

A. Mansour, W. Abd-Allah, N. El-Alaily, F. Ezz-Eldin, Study of paramagnetic species in γ-irradiated lithium borate glasses doped with Cu2+ ions. J. Nucl. Technol. Appl. Sci. 1(4), 497–509 (2013)

R.L. Frost, R. Scholz, A. López, Y. Xi, L.M. Graça, Infrared and Raman spectroscopic characterization of the borate mineral hydroboracite CaMg [B3O4 (OH)3]2⋅3H2O—implications for the molecular structure. J. Mol. Struct. 1059, 20–26 (2014)

R.C. Lucacel, I. Ardelean, Comparative structural investigation of B2O3–MO–CuO glasses (MO → TeO2 or As2O–3) by FTIR and Raman spectroscopies. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 8(3), 1124 (2006)

A. Samir, M.A. Hassan, A. Abokhadra, L. Soliman, M. Elokr, Characterization of borate glasses doped with copper oxide for optical application. Opt. Quant. Electron. 51(4), 1–13 (2019)

C. Gautam, A.K. Yadav, A.K. Singh, A review on infrared spectroscopy of borate glasses with effects of different additives. Int. Schol. Res. Notices 2012, 428497 (2012)

M.R. Joya, J. Barba, A. Raba, Vibrational Raman modes and particle size analysis of cupric oxide with calcination temperature. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. (IJPAP) 57(4), 268–271 (2019)

V. Chekhovskii, Interpretation of the IR spectra of alkali borate glasses. Sov. J. Glass Phys. Chem. 11, 1 (1985)

H. ElBatal, A. Abdelghany, I. Ali, Optical and FTIR studies of CuO-doped lead borate glasses and effect of gamma irradiation. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 358(4), 820–825 (2012)

F. ElBatal, S. Marzouk, N. Nada, S. Desouky, Gamma-ray interaction with copper-doped bismuth–borate glasses. Physica B 391(1), 88–97 (2007)

Y.B. Saddeek, E.R. Shaaban, H.M. Moustafa, Spectroscopic properties, electronic polarizability, and optical basicity of Bi2O3–Li2O–B2O3 glasses. Physica B 403(13–16), 2399–2407 (2008)

U. Chanshetti, V. Sudarsan, M. Jogad, T. Chondhekar, Effect of CuO addition on the optical and electrical properties of sodium zinc borophosphate glasses. Physica B 406(14), 2904–2907 (2011)

W. Abd-Allah, H. Saudi, K.S. Shaaban, H. Farroh, Investigation of structural and radiation shielding properties of 40B2O3–30PbO–(30–x) BaO-x ZnO glass system. Appl. Phys. A (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-019-2574-0

I. Kashif, A. Soliman, H. Farouk, M. El-Shorpagy, A. Sanad, Effect of copper addition on density and magnetic susceptibility of lithium borate glasses. Physica B 403(21–22), 3903–3906 (2008)

H. ElBatal, A. Abdelghany, F. ElBatal, K.M. ElBadry, F. Moustaffa, UV–visible and infrared absorption spectra of gamma irradiated CuO-doped lithium phosphate, lead phosphate and zinc phosphate glasses: a comparative study. Physica B 406(19), 3694–3703 (2011)

N. Mott, E. Davis, Electronic processes in non-crystalline materials, 2nd edn. (Clarendon, Oxford, 1979)

K. Aly, N. Afify, A. Abousehlly, A. AbdElnaeim, Optical band gap and refractive index dispersion parameters of In–Se–Te amorphous films. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 357(10), 2029–2034 (2011)

M. Azlan, M. Halimah, S. Shafinas, W. Daud, Polarizability and optical basicity of Er3+ ions doped tellurite based glasses. Chalcogenide Lett 11(7), 319 (2014)

M. Thombare, R. Joat, D. THombre, V. Mahavidyalaya, Glasses study physical properties of sodiumborophosphate. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 8482 (2016).

G. Baym, G. Brown, The Lorentz-Lorenz correction. Nucl. Phys. A 247(3), 395–410 (1975)

S.W. McKeever, Thermoluminescence of Solids (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1988)

J. Peng, Z. Dong, F. Han, tgcd: An R package for analyzing thermoluminescence glow curves. SoftwareX 5, 112–120 (2016)

Z.G.P. Uçar, Thermoluminescence characteristics and kinetic analysis of beta irradiated Ca4LaO (BO3)3 phosphor. Cumhuriyet Science Journal 42(3), 702–714 (2021)

A. El-Bayoumi, H.A. Alazab, F. Ezz-ElDin, The impact of γ-irradiation on Cd-B2O3 glass doped WO3: New evidences by TL and ESR spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 551, 120459 (2021)

C. Furetta, Handbook of Thermoluminescence (World Scientific, Singapore, 2003)

S. Farouk, A. Gad, H. Al-Azab, H. El-Nashar, N. El-Faramawy, Thermoluminescence response and its kinetic analysis of a natural milky quartz associated with tin-tungsten-fluorite mineralization. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 181, 109333 (2021)

S.W. McKeever, M. Moscovitch, P.D. Townsend, Thermoluminescence dosimetry materials: properties and uses. J. Radiol. Protect. (1995). https://doi.org/10.1088/0952-4746/16/4/018

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). There are currently no Funding Sources on the list.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All of the authors have taken full responsibility for the content of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Informed consent

The authors consent to participate.

Consent for publication

The author's consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdou, N.Y., El-Faramawy, N. & Abd-Allah, W.M. Dosimetric properties of potassium magnesium borate glass doped with copper. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 33, 12927–12940 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-022-08235-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-022-08235-4