Abstract

Social pension programs are a popular policy instrument to improve the well-being of the elderly and their households. However, evidence regarding the intra-household spillover effect of social pensions on children’s education remains limited. Using data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), this study empirically examined the associations between the cash transfers from the New Rural Pension Scheme (NRPS) for the eligible older adults and children’s educational outcomes in rural China. The results showed that the NRPS had significant intra-household spillover effects on children’s school enrollment and literacy skills. The findings were robust to a suite of robustness checks. Further, the associations of the NRPS with children’s educational outcomes were stronger for children who were boys, at a younger age, left behind by parents, and lived in economically disadvantaged families. We explored the potential mechanisms and found that the increase of childcare from grandparents and parents, accompanied by the improvement of physical and mental health, as well as learning behaviors of children, were the main possible channels behind the relationships between the NRPS and children’s schooling outcomes. Our findings shed new light on the effects of social pensions in rural China and provide insights on the policy improvement for the human capital development of disadvantaged children in developing countries like China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data used in this study are available from the authors upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Change history

09 November 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09874-9

Notes

According to the World Bank Open Data (WBOD), the percentage of the population aged 65 and above in China has increased dramatically over the past three decades, from 5.63% in 1990 to 11.97% in 2020. It is estimated that by 2050, over 25.6% of China’s population will be over age 65 (Chen et al., 2018).

As documented in Zhou et al. (2015), more than half of the primary school-aged children in rural China were not ready for the next stage of education. A recent study demonstrated a high level of developmental delay rate on cognitive skills among rural children in Henan and Anhui province of China, with 35.1% for children living with parents and 38.5% for left-behind children (Zhao et al., 2019).

Conversely speaking, the caregivers of children in poor families often have lower levels of physical and mental health, which could adversely affect their ability and preference to better nurture children. As such, children from disadvantaged families are more likely to be abused or neglected, resulting in decreased language skills and learning attention, psychological egoism, and hostility in the classroom (Akee et al., 2018). Such an effect on child personality traits and behavior plays a negative role in their schooling outcomes (Deng & Tong, 2020).

Note that the pre-condition of social pension receipt of rural older adults is that their adult children had already participated in the NRPS program. As a result, the rural elderly may not fully participate in the NRPS program even if the county was covered by the pension scheme. In addition, there are also several other possible reasons that some rural older people were not the enrollees of the program. First, China had once experimented on and off a rural pension scheme from the 1980s to 1990s and placed most of the financial responsibility on individuals. Some older adults who had participated in the old pensions scheme may not trust that the policy could offer a non-contributory pension, especially at the early stage of the NRPS program implementation. Second, some local governments need time to arrange corresponding organizations and staff to implement and publicize the NRPS program, including setting up individual accounts, making sure the authenticity of the information provided by applicants, and preparing policy advocacy documents. Third, it also takes some time for rural residents to know the newly implemented program. Potential enrollees may also need time to judge the effects of the NRPS program, either through official publicity or their peers that were already enrolled in the pension scheme.

Specifically, the baseline survey in 2010 did not include the measures about the NRPS and the 2012 wave of the survey did not have information on children’s cognitive assessments. Meanwhile, the 2016 and 2018 waves of the CFPS data did not separate the NRPS cash transfers from other pension insurances.

Among them, the literacy test had 8 groups of items with approximately the same difficulty level for children aged 10 – 15 years, each group had 34 characters, arranged in order from easy to difficult. The system randomly chose a group of words and the interviewers asked the respondents at different starting points according to their educational level. The maximum number of characters correctly reported by the respondents is scored as their literacy test scores (0 – 34). The math test questions were divided into 4 groups at almost the same difficulty level and each group had 24 questions. With the same procedures as the literacy test performed, child math test scores were measured, ranging from 0 – 24. More details about the cognitive assessments can be retrieved from the user’s manual of the CFPS (available at http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20180928161838082277.pdf).

As such, when we used the standardized scores as dependent variables, the slopes of linear regression models could be explained as the variation of the standard deviation of test scores with the variation of independent variables.

As stated in the official documents, the first-round pilot counties across regions were evenly distributed by the government, whereas counties in the middle and western regions implemented the NRPS policy earlier in later expansions (Huang & Zhang, 2021). To better meet the exclusion restriction assumption of the first IV used in this study, in practice, we collected the first-round pilot counties (about 320) released by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of China and matched them with the CFPS data.

The PSM analysis for the present study has three steps. First, we used a logistic regression model to estimate the propensity score of having an NRPS pensioner in the household. Second, the propensity score was used to match the children with and without an NRPS pensioner in a household within the common support region by different matching techniques, and the balance tests were conducted to ensure that the characteristics of the two groups were similar. Third, the mean differences of children’s school enrollment and academic achievement between the matched groups with balanced characteristics were estimated as the treatment effects of the NRPS pensions on children’s educational outcomes.

Since the 2012 wave of the CFPS survey has no similar cognitive assessments for children, school enrollment and school performance reported by parents were dependent variables in this robustness check.

We divided our sample into subsamples according to child gender (boy and girl), child age (3 – 5 for preschool children, 6 – 11 for primary school children, and 12 – 15 for junior-senior high school), parental migration status or left-behind status of children (whether father or mother had migrated to cities for more than 6 months), and family income (lower 50% and upper 50% of the sample according to annual family income per capita). It should be noted that literacy and math tests were for children aged 10 – 15 and parent-report academic performance was for children aged 6 – 15. Hence, the heterogeneity analysis by age groups for educational outcomes other than school enrollment was not applicable for the group of 3 – 5 years of age.

We conducted seemingly unrelated estimations for subsamples and statistically test the between-group differences in coefficients of the NRPS variable.

We took the logarithm of the educational expenditures to make the coefficients easier to interpret.

Specifically, we investigated the relationship between the NRPS and childcare provided by grandparents in Panel A. The measures of childcare from grandparents were whether they were the main caregivers of children in daytime and night. Similarly, childcare provided by parents and others (such as self-care) as main caregivers in daytime and night were used as dependent variables in Panel B and Panel C, respectively.

Among them, HAZ was comparable across different genders and ages and was widely used as a child health indicator (Goode et al., 2014). In particular, HAZ was calculated using: \({Z}_{i}={(y}_{ij}-\overline{{y }_{\dot{j}}})/{\sigma }_{j}\), where \({y}_{i}\) is the height (cm) of child \(i\) in group \(j\). Group \(j\) is defined by gender and age, with age measured in months by the date of the interview. \(\overline{{y }_{\dot{j}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{j}\) are the mean and standard deviation of the height (cm) of the reference group \(j\) of children of same gender and age according to World Health Organization (WHO) child growth standards. Child sickness was measured by the frequency of medical visits in the past year. Depression status was measured by the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (Kessler et al., 2002), which contains 6 questions about the following feelings during the past month: sad, nervous, restless or fidgety, hopeless, everything is an effort, worthless. The responses of each question range from 0 (none of the time) to four (all of the time) and the total score for the six items on the scale ranges from 0 to 24. The higher the K6 score, the higher levels of depression of the respondents. Health insurance (yes = 1) was used as a proxy variable of child health care.

The community characteristics included whether the community had a store (yes = 1), kindergarten (yes = 1), primary school (yes = 1), junior high school (yes = 1), hospital (yes = 1) and whether the community was an ethnic minority area (yes = 1).

References

Akee, R., Copeland, W., Costello, E. J., & Simeonova, E. (2018). How does household income affect child personality traits and behaviors? American Economic Review, 108(3), 775–827. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20160133

Caucutt, E. M., & Lochner, L. (2020). Early and late human capital investments, borrowing constraints, and the family. Journal of Political Economy, 128(3), 1065–1147. https://doi.org/10.1086/704759

Chen, X., Wang, T., & Busch, S. H. (2019). Does money relieve depression? Evidence from social pension expansions in China. Social Science & Medicine, 220, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.004

Cheng, L., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2018). The health implications of social pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2016.12.002

Currie, J. (2009). Healthy, wealthy, and wise: Socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 87–122. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.1.87

Dahl, G. B., & Lochner, L. (2012). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the earned income tax credit. American Economic Review, 102(5), 1927–1956. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2085200

Deng, L., & Tong, T. (2020). Parenting style and the development of noncognitive ability in children. China Economic Review, 62, 101477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101477

Duflo, E. (2003). Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. The World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhg013

Duncan, G. J., Morris, P. A., & Rodrigues, C. (2011). Does money really matter? Estimating impacts of family income on young children’s achievement with data from random-assignment experiments. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1263–1279. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023875

Eggleston, K., Sun, A., & Zhan, Z. (2018). The impact of rural pensions in China on labor migration. The World Bank Economic Review, 32(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhw032

Eide, E. R., Showalter, M. H., & Goldhaber, D. D. (2010). The relation between children’s health and academic achievement. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(2), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.08.019

Galiani, S., Gertler, P., & Bando, R. (2016). Non-contributory pensions. Labour Economics, 38, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2015.11.003

Goode, A., Mavromaras, K., & Zhu, R. (2014). Family income and child health in China. China Economic Review, 29, 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2014.04.007

Hair, N. L., Hanson, J. L., Wolfe, B. L., & Pollak, S. D. (2015). Association of child poverty, brain development, and academic achievement. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(9), 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1475

He, Z., Fang, X., Rose, N., Zheng, X., & Rozelle, S. (2021). Rural minimum living standard guarantee (rural Dibao) program boosts children’s education outcomes in rural China. China Agricultural Economic Review, 13(1), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-05-2020-0085

Heckman, J. J., & Mosso, S. (2014). The economics of human development and social mobility. Annual Review of Economics, 6(1), 689–733. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-040753

Hill, C. J., Bloom, H. S., Black, A. R., & Lipsey, M. W. (2008). Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Development Perspectives, 2(3), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00061.x

Huang, W., & Zhang, C. (2021). The power of social pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 13(2), 179–205. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170789

Jones, D., Molitor, D., & Reif, J. (2019). What do workplace wellness programs do? Evidence from the Illinois workplace wellness study. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(4), 1747–1791. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz023

Kabeer, N., & Waddington, H. (2015). Economic impacts of conditional cash transfer programmes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 7(3), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2015.1068833

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kilburn, K., Handa, S., Angeles, G., Mvula, P., & Tsoka, M. (2017). Short-term impacts of an unconditional cash transfer program on child schooling: Experimental evidence from Malawi. Economics of Education Review, 59, 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.06.002

Lalive, R., & Parrotta, P. (2017). How does pension eligibility affect labor supply in couples? Labour Economics, 46, 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.10.002

Li, L., Huang, L., Shi, Y., Luo, R., Yang, M., & Rozelle, S. (2018). Anemia and student’s educational performance in rural Central China: Prevalence, correlates and impacts. China Economic Review, 51(620), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.07.006

Li, Z., & Qiu, Z. (2018). How does family background affect children’s educational achievement? Evidence from Contemporary China. Journal of Chinese Sociology, 5(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-018-0083-8

Maluccio, J. A., Murphy, A., & Regalia, F. (2010). Does supply matter? Initial schooling conditions and the effectiveness of conditional cash transfers for grade progression in Nicaragua. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 2(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439340903584085

Mosterta, C. M., & Castello, J. V. (2020). Long run educational and spillover effects of unconditional cash transfers: Evidence from South Africa. Economics & Human Biology, 36, 100817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.100817

Ning, M., Gong, J., Zheng, X., & Zhuang, J. (2016). Does the new rural pension scheme decrease elderly labor supply? Evidence from CHARLS. China Economic Review, 41, 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.04.006

Qi, D., & Wu, Y. (2015). A multidimensional child poverty index in China. Children and Youth Services Review, 57, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.08.011

Shu, L. (2018). The effect of the New Rural Social Pension Insurance program on the retirement and labor supply decision in China. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 12, 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2018.03.007

Zhao, Q., Wang, X., & Rozelle, S. (2019). Better cognition, better school performance? Evidence from primary schools in China. China Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2019.04.005

Zhao, Q., Yu, X., Wang, X., & Glauben, T. (2014). The impact of parental migration on children’s school performance in rural China. China Economic Review, 31, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2014.07.013

Zheng, X., Fang, X., & Brown, D. S. (2020a). Social pensions and child health in rural China. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(3), 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1577387

Zheng, X., Shangguan, S., & Fang, X. (2020b). A literature review of research on the effect of the new rural pension scheme. Issues in Agricultural Economy, 5, 79–91. (in Chinese).

Zhong, H. (2011). The impact of population aging on income inequality in developing countries: Evidence from rural China. China Economic Review, 22(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2010.09.003

Zhou, C., Sylvia, S., Zhang, L., Luo, R., Yi, H., Liu, C., Shi, Y., Loyalka, P., Chu, J., Medina, A., & Rozelle, S. (2015). China’s left-behind children: Impact of parental migration on health, nutrition, and educational outcomes. Health Affairs, 34(11), 1964–1971. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0150

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 72003173), Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant number: 20YJC790187), National Statistical Science. Research Project (Grant number: 2021LY095), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant number: LY21G030008), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang (Grant number: XR202206).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the article; SS: interpretation of data, drafting of the article; ZS: critical revisions; HY: critical revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Due to few correction in text and Table 7 has been corrected.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

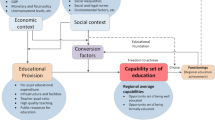

See Fig. 1 and Tables 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, X., Shangguan, S., Shen, Z. et al. Social Pensions and Children’s Educational Outcomes: The Case of New Rural Pension Scheme in China. J Fam Econ Iss 44, 502–521 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09850-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09850-3