Abstract

A better understanding of the reasons for bequests can be pivotal for fiscal policy and wealth inequality management, as the different motives underlying bequest behavior have varied implications. This study examines bloodline-based indirect reciprocity in bequest attitudes over three generations. In doing so, it extends the family tradition model to a bloodline-based family tradition model. This extended model suggests that the source of the inheritance impacts the amount of the bequest left to one’s children or spouse. To test the hypothesis, this study empirically analyzes survey data from the 2009 wave of the Preference Parameters Study for Japan. The results suggest that with some socioeconomic characteristics controlled for, those who have received an inheritance from their parents are more likely to intend to bequest as much as possible to their children, while Japanese females (males) who have received an inheritance from their spouse’s parents are more likely to intend to bequest as much as possible to both their children and their spouse (their spouse only). Hence, the source of the inheritance does matter in bequest attitudes, suggesting bloodline-based indirect reciprocity in bequest attitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A better understanding of the reasons for bequests can be pivotal for fiscal policy and wealth inequality management, as the different bequest motives underlying bequest behavior have divergent implications. For example, family tradition in bequeathing behavior may moderate inheritance/estate tax effectiveness (Stark & Nicinska, 2015). Wealthy households are more likely to save a large number of assets and bequeath them to the next generation, and thus, wealth inequality could grow due to voluntary bequests (De Nardi, 2004).

The reasons individuals leave bequests have been examined extensively in the literature, and the motives, which involve two generations, have been categorized mostly into self-interest and altruism. However, extant empirical results have been mixed. Some studies support the self-interest bequest motive, including accidental and strategic bequest (Bernheim et al., 1985; Cox, 1987; Hurd, 1997), while others support the altruistic one (Page, 2003; Tomes, 1981).

Another similar research stream has focused on intended bequest behavior involving three generations, which provides a new perspective of “family tradition” (Arrondel & Grange, 2014; Cox & Stark, 2005; DeBoer & Hoang, 2017; Niimi & Horioka, 2018; Stark & Nicinska, 2015). These studies demonstrate that intended bequest behavior is positively associated with the retrospective inheritance experience, providing evidence of indirect reciprocity in financial transfer behavior within the family (Arrondel & Masson, 2001; Bethencourt & Kunze, 2019).

These studies of family tradition examine the retrospective inheritance experience as a whole, irrespective of the source of the inheritance. However, mental accounting theory suggests that the source matters, as the principle of fungibility is violated across mental accounts (Thaler, 1985, 1990, 1999). Further, laboratory experiments of one-shot dictator games confirm the salience of the source (Cherry, 2001; Cherry et al., 2002).

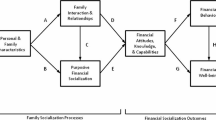

This study fills the gap in the literature by considering the source of the inheritance. In particular, it examines the existence of bloodline-based indirect reciprocity in the bequest attitude involving three generations. Family is identified by consanguineal kinship (see Figure 1). The first family includes the respondent’s parents, the respondent, and the child(ren) (hereafter “respondent’s bloodline family”); the second family, the respondent’s spouse’s parents, the respondent’s spouse, and the child(ren) (hereafter “spouse’s bloodline family”).

According to the self-interest model, the experience of inheritance will not increase the respondent’s positive bequest attitudes toward the children or spouse when income and wealth are controlled, and neither will the source of the inheritance, since the utility from other family members will not enter the exclusively self-interested individual’s utility function. Nonetheless, according to the altruistic model, the experience of inheritance may augment positive bequest attitudes toward children and/or spouses when the expected utility gains from other family members exceed the expected disutility of the individual due to bequests since the utility from children and/or spouses directly enters the individual’s utility function. However, the inheritance source is irrelevant to the bequest attitudes in the altruistic model since “altruism is a form of unconditional kindness” (Fehr & Gächter, 2000b, p.160), altruistic behavior is not a reaction to others’ behavior. Hence, bequest attitudes toward children and spouses are unaffected by the source of the inheritance.Footnote 1

This study provides a theoretical model, called the bloodline-based family tradition (BBFT) model, considering bloodline-based indirect reciprocity by extending the “family tradition” model of Stark and Nicinska (2015). In the BBFT model, where mental accounting applies, the respondent may deposit the inheritance from their parents and spouses’ parents into different psychological accounts, such as “their own” account when they receive an inheritance from their parents and another account when receiving an inheritance from parents-in-law. Accordingly, their bequest attitudes toward children and spouses will differ. Theoretically, the BBFT model suggests that the source of the inheritance matters in bequeathing.

Empirically, this study uses survey data from the 2009 wave of the Preference Parameters Study of Osaka University in Japan for the empirical analysis. Bequest attitudes are measured using the respondent’s agreement with statements on leaving children/spouses as much inheritance as possible. The empirical results suggest that those who have received an inheritance from their parents tend to have a higher bequest attitude toward children; meanwhile, Japanese females who have received an inheritance from their spouse’s parents tend to have a higher bequest attitude toward both their children and their spouse and Japanese males tend to have a higher bequest attitude toward their spouse.

The Meiji Civil Code has a long-lasting effect on the Japanese family system, marriage, and parent–child relationships (Kagayama, 2004). In an old Japanese family “Ie” (household in English), the wife enters the husband’s house after marriage, and even now, the phrase “Otto no ie ni totsugu (marry into my husband’s family)” is used. Civil Code Article 750 stipulates that “a husband and wife shall adopt the surname of the husband or wife following that which is decided at the time of marriage” (Japanese Law Translation, n.d.-a); however, about 96% of wives choose the husband’s surname as the family name after marriage (Ministry of Health, 2016). In addition, the meaning of the Japanese traditional wedding dress “Shiromuku” is marrying while clothed in pure white to be dyed in the color of the husband’s family. These indicate that in Japanese culture, females are encouraged to devote themselves to their husbands’ families after marriage. In Japanese social norms, sons (especially the eldest son) usually inherit a large amount. In addition, eldest sons are obligated to live with and provide informal family caregiving for their parents (Horioka et al., 2018). Considering Japanese culture, Japanese males and females vary in creating psychological mental accounts to deposit the benefits after receiving an inheritance from the first generation.

This study contributes to the theoretical and empirical literature by showing that the source of the inheritance matters in bequest attitudes toward children and spouses, which cannot be observed in either the altruistic or the joy of giving models. Although Japan has a unique cultural background, this study can be a starting point to prompt more research on the source of the inheritance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The following sections review the literature, develop the theoretical models, and provide the data and sample selection criteria. The subsequent sections provide the empirical framework and results, and then interpret the results in terms of the BBFT model. The final section concludes with a discussion of this study.

Literature Review

Intergenerational Transfers Involving Two Generations

Theoretical and empirical studies involving two generations reveal two principal motives of bequest behavior: self-interest and altruism. Under the self-interest motive hypothesis, some studies suggest that individuals have no bequest motives but leave accidental bequests because of lifetime uncertainty (Abel, 1985; Davies, 1981; Hurd, 1997; Laitner, 2002; Yaari, 1965). However, other studies suggest that these bequests are intentional (Gale & Scholz, 1994; Page, 2003). Some studies also suggest that individuals use bequests to influence children’s behavior such as gaining their attention and/or paying for services provided by their children; this is called the “strategic bequest motive” (Bernheim et al., 1985). The empirical results are mixed, as some evidence supports the strategic bequest motive (Angelini, 2007; Bernheim et al., 1985; Cox, 1987; Cox & Rank, 1992; Horioka et al., 2018; Kotlikoff & Morris, 1989; Yamada, 2006), while other evidence does not (Arrondel & Masson, 2001; Perozek, 1998; Sloan et al., 1997; Tomes, 1981).

Under the altruistic motive hypothesis, some studies suggest that impure altruistic individual utility is driven by the size of the bequest, called the “joy of giving” (Abel & Warshawsky, 1988; Laitner, 2002), also called the egoistic model (Laitner & Ohlsson, 2001), or warm-glow giving (Andreoni, 1990). Others have suggested that post-mortem intergenerational transfers are motivated by altruism, in which a benevolent parent cares about family members’ utility (Barro, 1974; Becker, 1974). Some of the empirical literature supports altruistic reasons (MacDonald & Koh, 2003; Tomes, 1981), but other studies find little evidence to support such an idea (Wilhelm, 1996). Thus, as current studies provide mixed empirical results, there appears to be no consensus among scholars on why parents leave bequests to their children.

Intergenerational Transfers Involving Three Generations

Some studies have investigated the family tradition in bequest behavior involving three generations, concerning the relationship between inheritance receipt from previous generations and the intention to leave bequests to children. DeBoer and Hoang (2017) and Niimi and Horioka (2018) found a positive correlation between intention to bequeath (dummy variable) and the experience of receiving an inheritance (dummy variable) in the United States and Japan. Cox and Stark (2005) and Stark and Nicinska (2015) showed that the chance and subjective probability of leaving a bequest is positively associated with the experience of receiving an inheritance from U.S. and European data. Arrondel and Grange (2014) examined the amount of inheritance received and expected value of the bequest from data on 19th century western France and showed significant positive correlations in terms of quantity.

Kao et al. (1997) regressed the probability of expecting to leave an inheritance in terms of “yes,” “possibly,” and “no” on the amount of inheritance received; they reported significantly positive results when using five multiple imputed data sets individually, but insignificant results when combining those five data sets. They explained that the estimated coefficients of the amount of inheritance received vary across the five data sets, which may account for the insignificance of the combined results.

Thus, such family traditions have been verified in many studies, thereby providing us with another explanation of bequests aside from self-interest and/or altruistic reasons, as follows.

Fairness and Indirect Reciprocity

Fairness consideration has been documented substantially in the literature (Fehr & Gächter, 2000b; Fehr & Schmidt, 1999; Kahneman et al., 1986; Rees, 1993). In addition, evidence from experiments such as the ultimate game, public goods game, and trust game suggest that an individual’s behavior may be affected by fairness considerations (Fahr & Irlenbusch, 2000; Falk et al., 2003; Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003; Fehr & Gächter, 2000a). According to fairness considerations, positive or negative reciprocal behavior is motivated by how agreeable or mean someone is to another (Falk et al., 2003; Fehr & Gächter, 2000b).

Direct reciprocity is an interaction between two individuals, while indirect reciprocity involves more than two individuals (Nowak & Sigmund, 2005). Indirect reciprocity has been categorized into downstream and upstream reciprocity. Downstream reciprocity can be observed in many experiments where a third party rewards (punishes) a player who has been benign (hostile) to another (Engelmann & Fischbacher, 2009; Seinen & Schram, 2006). According to Nowak and Sigmund (2005), upstream reciprocity is based on a previous experience wherein an individual receives help from a person, who then passes the benevolence to someone else.

Theoretical Model

Stark and Nicinska (2015) proposed a “family tradition” bequest model where an individual’s utility depends positively on personal consumption, child consumption, and continuing the family tradition to bequeath. This model predicts that individuals with a family tradition plan to bequest more than those without a family tradition.

The family tradition of bequeathing can be labeled as upstream reciprocity, where parents leave a bequest to individuals and incentivize them to leave a bequest to their children and/or spouse. This study extends the family tradition model to a BBFT model. The study’s theoretical model concerning “family tradition,” connected with bloodline-based indirect reciprocity, is identified by consanguineal kinship within the family.

If the fungibility of money is not violated, the inheritance will not have different bequest intentions toward spouses and children. In other words, if an individual cherishes the family tradition of bequeathing, they will have similar bequest attitudes toward their spouse and children irrespective of the source of the inheritance, because the inheritances received from the first generation are stored in one psychological account.

If fungibility is violated, the inheritances from the individuals’ parents and their spouses’ parents may trigger different routes of reciprocity, because the inheritances are stored in separate psychological accounts. For example, those who have received an inheritance from their parents may regard it entirely as “their own,” having its exclusive possession from their parents, with no obligation to share with others. Consequently, if the BBFT of bequeathing applies, the respondent may consider leaving more to their children, but not to their spouse, who is not in the respondent’s bloodline family. Those who have received an inheritance from the parent-in-law may reckon being enabled to benefit from the inheritance because of marriage to that person. The benefits are not entitled into “their own” account but deposited in a different psychological account, for example, a new family account linked by affinal kinship. Owing to the benevolence of the parent-in-law or spouse’s generous sharing, for the fairness consideration, it is unfair to leave nothing to the spouse and/or children when an individual holds onto the BBFT of bequeathing. This study provides a unique contribution to the literature by analyzing the correlation between the source of the inheritance and intended bequest.

Here, the general utility functionFootnote 2 for each individual is given as

where \({Z}_{c}={b}_{c}-\theta \times {h}_{p}-{\gamma }_{c}\times {h}_{sp}\) and \({Z}_{s}={b}_{s}-{\gamma }_{s}\times {h}_{sp}\).

The individual’s utility \(U\) depends positively on personal consumption \({y}_{i}+{h}_{p}+{h}_{sp}-{b}_{c}-{b}_{s}\), the consumption of the child \({y}_{c}+{b}_{c}\), the consumption of the spouse \({y}_{s}+{b}_{s}\), and the family tradition of bequeathing \({Z}_{c}\) and\({Z}_{s},\)Footnote 3 where \(\text{y}\) represents income; \(h\) represents the inheritance received; the subscripts \(p\text{ and }sp\) denote the source of the inheritance from the individual’s parents and spouse’s parents, respectively; \(b\) represents the bequest; and the subscripts \(c\text{ and }s\) denote the child and spouse, respectively. The parameters \({\alpha }_{c},{\alpha }_{s}\ge 0\), and \(\left(1-{\alpha }_{c}-{\alpha }_{s}\right) >0\) measure altruism.

\({\beta }_{c},{\beta }_{s}\ge 0\) measures the family tradition of bequeathing. When \({h}_{p}+{h}_{sp}>0\), an individual receives an inheritance from the first generation. The individual derives utility from doing their part of leaving an inheritance if they value the family tradition of bequeathing regardless of the actual effect on the increase of the child’s and spouse’s consumption. In this case, higher \({\beta }_{c}\) and \({\beta }_{s}\) represent an individual who cherishes carrying on the family tradition of bequeathing more. When \({h}_{p}+{h}_{sp}=0\), an individual does not receive any inheritance from the first generation. In this case, higher \({\beta }_{c}\) and \({\beta }_{s}\) represent an individual who cherishes bequeathing more.

When mental accounting is applied, there is a BBFT. \(0\le \theta ,{\gamma }_{c},{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), and \({\gamma }_{c}+{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), where \(\theta \text{ and }{\gamma }_{c}\) measure the weights assigned to the child in their and their spouse’s bloodline families, and \({\gamma }_{s}\) is the weight assigned to the spouse in the spouse’s bloodline family. Higher \(\theta \text{ and }{\gamma }_{c}\) mean that the individual cares more about the child in the respondent’s bloodline and the spouse’s bloodline family, which leads to a larger \({b}_{c}\) to make the family tradition of bequeathing to the child (\({Z}_{c}\)) positive. A higher \({\gamma }_{s}\) means that the individual cares more about the spouse in the spouse’s bloodline family, which leads to a larger \({b}_{s}\) to make the family tradition of bequeathing to the spouse (\({Z}_{s}\)) positive. The larger the \(b\) value to the child and/or spouse, the higher the bequest attitudes.

For simplicity, the general model is separated into three cases: the pure altruistic model, pure joy of giving model, and pure BBFT model.

Pure Altruistic Model

In the case of pure altruism \(\left({\beta }_{c}={\beta }_{s}=0\right)\), \({\alpha }_{c},{\alpha }_{s},\text{ and} \left(1-{\alpha }_{c}-{\alpha }_{s}\right) >0\), an individual considers choosing the amount of the bequest for the child and the spouse to maximize the utility function, given as

Then, utility \(U\left({b}_{c},{b}_{s}\right)\) will reach its maximum (see the proof in Appendix A) when

If the inheritance from the respondent’s parents increases by \(\Delta \), the optimal bequests to the child and spouse are \({b}_{c,{h}_{p}+\Delta }^{*} \,\text{and} \,{b}_{s,{h}_{p}+\Delta }^{*}\), respectively; then, the bequest to the child and spouse increases, respectively by

If the inheritance from the spouse’s parents increases by \(\Delta \), the optimal bequests to the child and spouse are \({b}_{c,{h}_{sp}+\Delta }^{*} \,\text{and}\, {b}_{s,{h}_{sp}+\Delta }^{*}\), respectively; then, the bequest to the child and spouse increases, respectively by

The differences in the bequests with respect to the difference in the sources of inheritance are

Hence, in the case of pure altruism, the source of the inheritance does not affect an individual’s bequests.

Pure Joy of Giving Model

In the case of the pure joy of giving \(\left({\alpha }_{c}={\alpha }_{s}=0\right)\), \(\theta , {\gamma }_{c},{\gamma }_{s}=0,\) and \({\beta }_{c},{\beta }_{s}>0.\) Bequeathing is motivated by “warm-glow giving” (Andreoni, 1990). An individual considers choosing the number of bequests to the child and spouse to maximize the utility function, given as

Then, the utility \(U\left({b}_{c},{b}_{s}\right)\) will reach its maximum (see the proof in Appendix B) when

If the inheritance from the respondent’s parents increases by \(\Delta \), the bequest for the child and spouse increases respectively by

If the inheritance from the spouse’s parents increases by \(\Delta \), the bequest to the child and spouse increases, respectively by

The differences in the bequest to the difference in the sources of inheritance are as follows:

Hence, in the case of the pure joy of giving, the source of the inheritance does not affect the individual’s bequests.

Pure BBFT Model

In the case of the pure BBFT \(\left({\alpha }_{c}={\alpha }_{s}=0\right)\), \({\beta }_{c},{\beta }_{s}>0\), \(0<{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), \(\left|\theta \right|+\left|{\gamma }_{c}\right|\ne 0\),\(0\le \theta ,{\gamma }_{c}\le 1\), and \({\gamma }_{c}+{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\). An individual considers choosing the amount of the bequest to the child and spouse to maximize the utility function, given as

Then, the utility \(U\left({b}_{c},{b}_{s}\right)\) will reach its maximum (see the proof in Appendix C) when

If the inheritance from the respondent’s parents increases by \(\Delta \), the bequest to the child and spouse increases respectively by

If the inheritance from the spouse’s parents increases by \(\Delta \), the bequest to the child and spouse increases, respectively by

The differences in the increase in bequests to the difference in the source of the inheritance are

Proposition 1a. In the pure BBFT model, where \({\beta }_{c},{\beta }_{s}>0\), \(0<{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), \(\left|\theta \right|+\left|{\gamma }_{c}\right|\ne 0\),\(0\le \theta ,{\gamma }_{c}\le 1\), and \({\gamma }_{c}+{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), and the inheritance from the individual’s parents and from their spouse’s parents increases by the same amount \(\Delta \), ceteris paribus, the difference in the increase in the bequest to the child to the source of the inheritance (Eq. 27) is larger than zero when \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}}\); equals zero when \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)=\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}}\), and is less than zero when \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)>\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}}\).

Proposition 1b. In the pure BBFT model, where \({\beta }_{c},{\beta }_{s}>0\), \(0<{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), \(\left|\theta \right|+\left|{\gamma }_{c}\right|\ne 0\),\(0\le \theta ,{\gamma }_{c}\le 1\), and \({\gamma }_{c}+{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), and the inheritance from the individual’s and their spouse’s parents increases by the same amount \(\Delta \), ceteris paribus, the differences in the increase in the bequest to the spouse to the source of the inheritance (Eq. 28) is larger than zero when \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)>\frac{(1+{\beta }_{c}){\gamma }_{s}}{{\beta }_{s}}\); equals zero when \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)=\frac{(1+{\beta }_{c}){\gamma }_{s}}{{\beta }_{s}}\), and is less than zero when \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{(1+{\beta }_{c}){\gamma }_{s}}{{\beta }_{s}}\).

Only when \({\gamma }_{c}= \theta \text{ and }{\gamma }_{s}=0\) do both Eqs. (27) and (28) equal to zero, and the source of the inheritance does not affect the individual’s bequests to either the child or the spouse. However, in this case, this becomes a mixed model, a BBFT to the child and joy of giving to the spouse, rather than the pure BBFT model that assumes that \({\gamma }_{s}\) is larger than zero. For simplicity, this mixed-type model is not considered. Hence, in the case of the pure BBFT model, the increase in the bequest to the child or spouse varies according to the source of the inheritance.

Data and Sample Selection

The analysis in this study is based on the data from the Preference Parameters Study of Osaka University. The panel survey, which employs two-stage stratified random sampling, has been conducted in Japan since 2003. In the first stage, all cities are placed into ten regions: Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, Koshinetsu, Hokuriku, Tokai, Kinki, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu. In the second stage, in each region, the cities are categorized into four types according to size, ordinance designation, population (100,000 or more and less than 100,000), and towns and villages. Overall, there are 40 strata in total. In each stratum, men and women aged 20–69 years are drawn from the population.

The data used in this study are from the 2009 wave, which includes two predominant variables concerning respondents’ bequest attitudes toward children and spouses: “I want to leave my children as much of my inheritance as possible” (hereafter “bequest attitudes toward children”) and “I want to leave my spouse as much of my inheritance as possible” (hereafter “bequest attitudes toward the spouse”).Footnote 4 The 2009 wave was conducted from February to March 2009, with fresh samples selected and added.

There are 6,181 observations during this wave. Excluding those who do not answer the bequest attitude questions, there are 6,060 observations. Since this study focuses on respondents’ bequest attitudes toward children and spouses, the sample is restricted to those who are married (those who report that “I have a spouse [husband or wife, including common-law marriage]” in the survey) and have at least one child; hence, we are left with 4,466 observations. Excluding those who do not answer the questions on the source of the inheritance, 4,067 observations remain. Further, excluding missing values for gender, household income, the number of children in the family, religious faith, age, educational attainment, and employment status, we have 3,428 observations. Thus, the sample size decreases significantly. This might cause selection bias, and the results may not be representative.Footnote 5

Empirical Framework

Methodology

Bequest attitudes are captured as an ordered response. Hence, this study uses an ordered response model. The latent bequest attitudes are estimated as follows:

where \(BA\) represents bequest attitudes toward children and bequest attitudes toward the spouse. Let \({\varvec{X}}\) denote the vector of the socioeconomic characteristics, \({\varvec{\beta}}\) denote a \(K\times 1\) vector of the parameters, and \(\varepsilon \) denote the error term.

Let \({\omega }_{j}\) be the threshold, where \(j=\text{1,\,2},\text{3,\,4}\). Define the values of \(BA\) as follows:

The generalized ordered logit model (Williams, 2006) is written as

When all the coefficients \({\beta }_{j}\) are identical across \(j\) (\({\beta }_{j}=\beta \)), the model is the ordered logit model, which satisfies the parallel regression assumption (Wooldridge, 2010), and when only some of the coefficients are identical across \(j\), the model is the partial proportional odds (PPO) model (Williams, 2006, 2016) as follows:

where \({\beta }_{k}\) is identical for \({X}_{k,i} (k=\text{1,2},\dots t-1)\), and \({\beta }_{k,j}\) for \({X}_{k,i} (k=t,\dots K)\) can differ across \(j\).

Dependent Variables

The survey questions on bequest attitudes are “I want to leave my children as much of my inheritance as possible” (bequest attitudes toward children) and “I want to leave my spouse as much of my inheritance as possible” (bequest attitudes toward the spouse), measured on a five-point Likert scale and coded as 1, “Does not hold at all for me” and 5, “Particularly true for me.”Footnote 6

Table 1 shows that for those who answered both questions, about 42.39% and 41.48% of the respondents chose “3” for bequest attitudes toward children and bequest attitudes toward the spouse, respectively. Among Japanese women, 27.86% chose “4” or “5” for bequest attitudes toward children, while 31.22% of Japanese men followed suit. Only 15.97% of Japanese women chose “4” or “5” for bequest attitudes toward the spouse, while 43.07% of Japanese men chose those rankings. Japanese women tended to choose a lower triangular proportion, while Japanese men an upper, indicating that Japanese women were more likely to leave as much inheritance as possible to their children rather than their spouses, while Japanese men were more likely to leave as much as possible to their spouses than children.

Independent Variables

The predominant independent variable used in this study is “Have you received an inheritance (or transfer of wealth before death) from your parents or your spouse’s parents in the past?” The variable equals 1 if the respondent has received transfers from their parents (spouse’s parents) and 0 if they have not. This question captures the source of the inheritance.Footnote 7 If the respondent has received an inheritance from their parents (INH from parents), the bequest attitudes toward children would be expected to be positive. If the respondent has received an inheritance from the spouse’s parents (INH from parents-in-law), the bequest attitudes toward the spouse (and children) would be expected to be positive.

The survey also contains a question about whether the respondent expects to receive any wealth transfers, that is, “Do you expect that you will receive an inheritance (or transfer of wealth before death) from your parents or your spouse’s parents in the future?” This variable is controlled for in the regression separately as a dummy for expecting to receive an inheritance from parents (Expect INH from parents) and from the spouse’s parents (Expect INH from parents-in-law). Given that the mean of respondents’ ages in this study is 51.6 (Table 2), some respondents do not receive an actual inheritance until later in life. The expectation of receiving wealth transfers does not increase the respondents’ wealth at the time of answering the survey. Considering the attribution of fairness intention (Falk et al., 2003), intentions matter even if the final payoff is the same. The signs of expected inheritance dummies are predicted to be positive for those who expect to receive money transfers, as they would deem this as a generous intention from parents and/or parents-in-law. As a result, they intend to leave an inheritance after they die.

The other independent variables include socioeconomic characteristics such as a female dummy, household income, the number of children in the family, religious faith, life expectancy and its square, educational attainment, and employment status. The sign of the female dummy is expected to be negative in terms of bequest attitudes, as the previous literature finds the female dummy negatively correlated with the expectation of bequeathing (Niimi & Horioka, 2018).

The question “Approximately how much was the annual earned income before taxes and with bonuses included for your entire household for 2008?” is used to estimate annual household income and the answers are reported in 12 categories. This study uses the mid-point of each income category and assigns a value of half of the upper bound for the lowest category (JPY 500,000) and 1.5 times the lower bound for the highest (JPY 30,000,000). Household income is taken as a natural logarithm in the analysis. This sign is expected to be positively correlated with bequest attitudes.

The sign of the number of children in the family is expected to be negative. The more children the respondent has, the more support is needed and the lower is the ability to save for intentional bequests, given budget constraints.

Religious faith is captured by the statement that “I am deeply religious,” which is measured on a five-point Likert scale and coded as 1, “Doesn’t hold at all for me” and 5, “Particularly true for me.”Footnote 8 Ito et al. (2017) hypothesized that the existence of a temple may strengthen blood ties in Japan, as a Buddhist funeral is common in Japanese culture. In addition, graves of family members are often located in temples and the existence of temples intensifies blood ties with ancestors. They empirically found that the presence of a temple nearby is positively correlated with altruism and reciprocity. The sign is expected to be positive as religious faith reinforces family ties and the value of the family tradition.

This study uses life expectancy rather than respondents’ age because women outlive men in general. Data for 2005 to 2009 (OECD, n.d.) show that the five-year average effective ages of retirement for men and women are 69.5 and 66.7 years, respectively. Life expectancy (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, n.d.) at 70 years of age for men and 67 years for women was 15.10 and 22.21 years in 2009, respectively. Thus, the length of retirement for women is much longer than that for men. Since women have to prepare for a longer retirement than men, it is plausible to use life expectancy at each age in the analysis. The signs of life expectancy and its square are difficult to anticipate. Those who have longer life expectancy may have optimistic bequest plans and can achieve their goal of leaving as much as possible by saving more and/or working harder. Those who have shorter life expectancy may also have a higher bequest attitude since they have tried to do their best to leave adequate bequests.

Educational attainment is categorized into three groups: those who did not finish high school (no high school), those who graduated from high school but not from college (high school), and those who graduated from college or above. Educational attainment usually serves as a proxy for permanent income. In this case, well-educated respondents may intend to leave more inheritances since they are more likely to have a higher permanent income. In addition, well-educated respondents may care more about their children and spouse’s utility. Therefore, the sign is positive if the respondent has higher educational attainment. However, if well-educated respondents are more likely to invest in children’s human capital, the trade-off between human capital transfer and bequeathing later may lead the sign of bequest attitudes toward children to be negative. The combined effects from permanent income, consideration for other family members, and investment in human capital make it uncertain to predict the sign.

Employment status is categorized into three groups: full-time employees, part-time employees (including part-time employees, student part-time employees, temporary workers, contract workers, and others), and do not work (including those whose occupation is housewife/househusband, students, retired, unemployed, and others). Full-time employees are more capable of leaving an adequate inheritance than part-time employees and those who are not working. The workless are reliant on their spouses. Their willingness to leave as much inheritance as possible toward their spouse can raise reciprocity.

Table 2 presents the summary statistics of the dependent and independent variables (and respondents’ age for reference) in the regression. The means of bequest attitudes toward children and the spouse are 3.00 and 2.94, respectively and the difference is significant at the 1% level. Of the respondents, 24% and 16% reported inheritance from their parents and spouses’ parents, respectively.Footnote 9 The corresponding expectations of inheritance were 34% and 26%, respectively. Table 3 presents the means of each variable across the different levels of bequest attitudes. The means of Expect INH from parents increase with an increase in bequest attitudes toward both children and the spouse. The means of the female dummy decrease with an increase in bequest attitudes toward the spouse. The means of the number of children decrease with an increase in bequest attitudes toward children. The means of life expectancy increase with an increase in bequest attitudes toward children. The means of high school graduates increase with an increase in bequest attitudes toward children but decrease with an increase in bequest attitudes toward the spouse. The means of full-time employment increase with an increase in bequest attitudes toward both children and the spouse. The means of part-time workers decrease with an increase in bequest attitudes toward both children and the spouse.

Empirical Results

PPO Model

This study uses the PPO model because the Brant test shows that some of the variables violate the parallel regression assumption in the ordered logistic regression.Footnote 10

To examine how the predicted probabilities of bequest attitudes change as the independent variable changes, Table 4 presents the marginal effects at the means reported by the PPO model for different levels of bequest attitudes. The bequest attitudes toward children panel shows that the probability of higher bequest attitudes is greater when INH from parents, INH from parents-in-law, and Expect INH from parents equal one, among those who have higher household income, longer life expectancy, and high school educational attainment. The probability of lower bequest attitudes is higher when the respondents are female and have more children. The bequest attitudes toward the spouse panel shows the probability of higher bequest attitudes when INH from parents-in-law and Expect INH from parents equal one, among those who have higher household income, longer life expectancy, and those who do not work. There is a greater probability of lower bequest attitudes when the respondents are female and have a larger number of children.

In sum, those who inherit from their parents are more likely to leave as much bequest as possible to their children. Those who inherit from their spouses’ parents are more likely to leave as much bequest as possible to both their children and their spouses.

Gender Comparison

Considering the Japanese culture, as discussed in the introduction section, there is value in applying the same empirical framework as in the previous subsections, and the gender differences associated with the source of the inheritance are considered by analyzing the subsamples. Table 2 presents the summary statistics for Japanese women and men separately. The p-values with asterisks represent the mean differences between females and males for each variable. The bequest attitudes toward children and spouses were much higher among male respondents than females. More males received or expected to receive an inheritance from their parents than females, while more females received or expected to receive an inheritance from their spouse’s parents. This implies that a son’s family is more likely to receive a wealth transfer than a daughter’s family, which is consistent with the results of Niimi and Horioka (2018). Unlike Japanese males, Japanese females take their husband’s surname and are considered to be under the protection of the husband’s family; consciously, they are perceived as belonging to their husband’s family. Hence, females are more likely to (expect to) receive an inheritance from parents-in-law than males.

There were no significant gender differences in household income, the number of children, or religious faith. Male respondents in the sample are older than their female counterparts and their corresponding life expectancy is much lower than that of females. Regarding educational attainment, more males graduated from college or above than females. Concerning employment status, more males are full-time employees, while more females are part-time and not working.

Table 5 shows the marginal effects (the full specifications are presented in Appendix D). The results suggest that females who have received INH from parents are more likely to have higher bequest attitudes rather than lower bequest attitudes toward children and that those who have received INH from parents-in-law are more likely to have higher bequest attitudes rather than lower bequest attitudes toward both children and the spouse. The results suggest that males who have received INH from parents are more likely to have higher bequest attitudes than lower bequest attitudes toward children and that those who have received INH from parents-in-law are more likely to have somewhat higher bequest attitudes toward the spouse.

Empirical Results and Pure BBFT Model

Bequest Attitude Differs Across the Sources of Inheritance

For simplicity, significant marginal effects indicate that an individual will leave more bequest than insignificant marginal effects.Footnote 11 The effect of the source of the inheritance assesses the relationships between INH from parents and parents-in-law and bequest attitudes toward children as well as between INH from parents and parents-in-law and bequest attitudes toward the spouse.

The significant marginal effects of INH from parents and parents-in-law related to bequest attitudes toward children in the female subsample imply that Eq. (27) is equal to zero. In the pure BBFT model, \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)=\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}},\) in this case.

The significant marginal effects of INH from parents but insignificant marginal effects of INH from parents-in-law related to bequest attitudes toward children in the male subsample imply that Eq. (27) is higher than zero. In the pure BBFT model, \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}},\) in this case.

The insignificant marginal effects of INH from parents but significant marginal effects of INH from parents-in-law related to bequest attitudes toward the spouse in both the female and the male subsamples imply that Eq. (28) is less than zero. In the pure BBFT model, \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{(1+{\beta }_{c}){\gamma }_{s}}{{\beta }_{s}},\) in this case.

For the female subsample, \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)=\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}}\) and \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{(1+{\beta }_{c}){\gamma }_{s}}{{\beta }_{s}}\). For the male subsample, \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{{\beta }_{c}{\gamma }_{s}}{1+{\beta }_{s}}\) and \(\left({\gamma }_{c}-\theta \right)<\frac{(1+{\beta }_{c}){\gamma }_{s}}{{\beta }_{s}}\). These inequalities can hold simultaneously.The pure BBFT model is thus sufficient to explain the empirical results.

Gender Analysis

The main differences in the gender comparison are the positive significant marginal effects of INH from parents-in-law on bequest attitudes toward both children and spouses in the female subsample compared with the insignificant ones of bequest attitudes toward children and some significant marginal effects related to bequest attitudes toward spouses in the male subsample. Assuming the significant coefficients represent more bequest, under the pure BBFT model, this difference implies that \(\left\{{\left.{b}_{c,{h}_{sp}+\Delta }^{*}-{b}_{c}^{*}\right|}_{female}\right\}>\left\{{\left.{b}_{c,{h}_{sp}+\Delta }^{*}-{b}_{c}^{*}\right|}_{male}\right\}\) and \(\left\{{\left.{b}_{s,{h}_{sp}+\Delta }^{*}-{b}_{s}^{*}\right|}_{female}\right\}>\left\{{\left.{b}_{s,{h}_{sp}+\Delta }^{*}-{b}_{s}^{*}\right|}_{male}\right\}\).

Situation 1: Suppose \({\beta }_{cf}={\beta }_{cm}={\beta }_{c}\) and \({\beta }_{sf}={\beta }_{sm}={\beta }_{s}\)

Then, it is equivalent to \(\frac{{\beta }_{c}}{\left(1+{\beta }_{s}\right)}\left({\gamma }_{sf}-{\gamma }_{sm}\right)<\left({\gamma }_{cf}-{\gamma }_{cm}\right)<\frac{\left(1+{\beta }_{c}\right)}{{\beta }_{s}}\left({\gamma }_{sf}-{\gamma }_{sm}\right)\). Since, \(0<\frac{{\beta }_{c}}{\left(1+{\beta }_{s}\right)}<\frac{\left(1+{\beta }_{c}\right)}{{\beta }_{s}}\), the necessary condition \({\gamma }_{sf}>{\gamma }_{sm}\text{ and }{\gamma }_{cf}>{\gamma }_{cm}\) implies that females care more about the weights assigned to the child and spouse in the spouse’s bloodline family than males.

Situation 2: Suppose \({\gamma }_{cf}={\gamma }_{cm}={\gamma }_{c}\) and \({\gamma }_{sf}={\gamma }_{sm}={\gamma }_{s}\)

Since \(1-{\gamma }_{c}-{\gamma }_{s}>0,\) then, it is equivalent to \(\frac{{\beta }_{cf}}{{\beta }_{cm}}>\frac{1+{\beta }_{sf}}{1+{\beta }_{sm}}\) and \(\frac{{\beta }_{sf}}{{\beta }_{sm}}>\frac{1+{\beta }_{cf}}{1+{\beta }_{cm}}\). In this case, the necessary condition \({\beta }_{cf}>{\beta }_{cm}\) and \({\beta }_{sf}>{\beta }_{sm}\) (see the proof in Appendix E) implies that females care more about the family tradition to the child and spouse than males.

Hence, to explain the gender differences, under the pure BBFT model, suppose \({\beta }_{cf}={\beta }_{cm}={\beta }_{c}\) and \({\beta }_{sf}={\beta }_{sm}={\beta }_{s}\), when \({\gamma }_{sf}>{\gamma }_{sm}\) and \({\gamma }_{cf}>{\gamma }_{cm}\); or suppose \({\gamma }_{cf}={\gamma }_{cm}={\gamma }_{c}\) and \({\gamma }_{sf}={\gamma }_{sm}={\gamma }_{s}\), when \({\beta }_{cf}>{\beta }_{cm}\) and \({\beta }_{sf}>{\beta }_{sm}\), the pure BBFT model is sufficient to explain the empirical results. This suggests that females are more likely to assign higher weights to the child and spouse in the spouse’s bloodline family or a higher family tradition to the child and spouse than males.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study examines bloodline-based indirect reciprocity in bequest attitudes involving three generations. The theoretical model, called the BBFT model, extends the “family tradition” model proposed by Stark and Nicinska (2015) and includes bloodline-based indirect reciprocity driven by the fairness consideration and mental accounting theory. Theoretically, the pure BBFT model suggests that the source of the inheritance has a different impact on bequeathing.

The empirical analysis uses survey data from the 2009 Preference Parameters Study of Osaka University in Japan. The results of the PPO regression suggest that with some socioeconomic characteristics controlled for, Japanese females who have an inheritance from either their parents or their spouse’s parents intend to leave as much bequest as possible to their children; while once they have an inheritance from their spouse’s parents, they intend to leave as much bequest as possible to their spouse. For Japanese males who have an inheritance from their parents, they intend to leave as much bequest as possible to their children, while once they have an inheritance from their spouse’s parents, the bequest attitudes toward children are unaffected, but the intention to their spouse increases. Hence, the source of the inheritance does matter in bequest attitudes, suggesting that there is bloodline-based indirect reciprocity in bequest attitudes.

For Japanese females, those who have received an inheritance from their parents put the money in “their own” account and pass it onto their children, while those have who received an inheritance from their spouse’s parents put the money in the new nuclear family account and intend to leave as much as possible to both their children and their spouses. For Japanese males, those who have received an inheritance from their parents deposit the money in “their own” account and pass it onto children, like Japanese females, but deposit the money from their spouse’s parents in another psychological account for affinal kinship and reciprocate their wives. The empirical results are consistent with the theoretical prediction from the BBFT model that the increase in bequest attitudes toward children and spouses varies according to the source of the inheritance.

The results in Table 4 suggest that females are less likely to have higher bequest intentions to both children and the spouse than males, while the results in Table 5 show that females have positive bequest attitudes associated with the inheritance received. One explanation for the results is that females are incapable of leaving as much inheritance as possible since most of them are dependent,Footnote 12 but cherish the family tradition of bequeathing.

The gender differences in bequest attitudes show that females pay more attention to the weights assigned or follow stronger family traditions to the child and spouse than males. These results suggest that females are more likely to apply fairer consideration than males, consistent with the results of Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001). Since Stark and Nicinska (2015) argued that the family tradition may moderate the effectiveness of the inheritance tax and the empirical results from Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001) indicated that females are less price elastic than males, the empirical results from this study suggest that the taxation on inheritance is less functional for females than for males.

In addition, the empirical results from the gender differences in bequest attitudes suggest that, for Japanese females, intergenerational wealth inequality will expand if they have received a transfer from the previous generations regardless of the source of the inheritance. However, intergenerational wealth inequality may not expand if Japanese males have received a transfer from their parents-in-law.

Bequeathing between spouses is less likely to be affected by the inheritance tax because of the reduction of inheritance tax for the spouse. Japanese males who have received an inheritance from their parents-in-law are more likely to intend to leave more bequest to their wives. Considering the length of retirement for women is much longer than that for men and that women usually outlive men, this intragenerational transfer alleviates women’s anxiety about old age expenditure.

The results of this study must be considered cautiously. First, bequest attitudes were captured by asking if the respondents agreed with the statement that they would leave as much of their bequest as possible to their children and spouse. Even when the empirical results are not significant, this does not mean that the individuals will leave nothing to their children and spouses.

Second, although the empirical results do not violate the simplest pure BBFT model, the intention to bequeath may be more complex. For example, for the full sample and female subsample, both INH from parents and INH from parents-in-law have positive significant effects on bequest attitudes toward children, which can be explained simply by either the altruistic model or the joy of giving model. Therefore, further investigation into a general model that combines altruism (or the joy of giving) and the BBFT is required.

Third, data limitations preclude this study from further analysis of the amount of inheritance received and bequest intended. In addition, the predominant independent variables concerning inheritance received (or wealth transfers before death) do not separate it from inter vivos transfers. Therefore, further research is required.

Notes

For simplicity, this study does not consider the tough love (Bhatt & Ogaki, 2012) reason for the unwillingness to bequeath as much as possible to children and/or spouses (e.g., leaving too much may sabotage self-development). Moreover, the empirical results suggest that the proportion of tough love is relatively limited (Horioka, 2014).

The utility function is in the log form because 1) it assumes the utility gains from the consumption and net bequeathing amount are marginally decreasing, 2) the model in this form has a unique maximum, and 3) the model proposed by Stark and Nicinska (2015) is in the log form.

When mental accounting does not apply, there is no BBFT. \({Z}_{c}={b}_{c}-{\lambda }_{c}\times h\) and \({Z}_{s}={b}_{s}-{\lambda }_{s}\times h\), where \(h={h}_{p}+{h}_{sp}$$.$$0\le {\lambda }_{c},{\lambda }_{s}\le 1\) and \({\lambda }_{c}+{\lambda }_{s}\le 1\), where \({\lambda }_{c}\) and \({\lambda }_{s}\) measure the weights assigned to the child and spouse in the family . A higher \({\lambda }_{c}\) and \({\lambda }_{s}\) require a larger \({b}_{c}\) and \({b}_{s}\) to make the family tradition of bequeathing positive irrespective of the inheritance source.

A total of 2.23% of Japanese females and 5.80% of Japanese males chose “Particularly true for me” for both questions. In this case, the amount of bequest is not fixed, and the respondent decreases their consumption to increase the bequeath to both children and spouses. Some respondents may trade off between bc and bs given the amount of the bequest is fixed. Suppose respondents’ lifetime consumption is constant or changes slightly after receiving an inheritance from previous generations, which may also fit the model. I thank the referee for pointing this out. Article 890 of the civil law states that “the spouse of a decedent shall always be an heir” (Japanese Law Translation, n.d.-b). Those who claim to leave as much inheritance as possible to spouses tend to decrease consumption and increase the bequeath.

The main concern is if there is a significant difference in bequest attitudes between the 1038 (4466–3428) observations of those who are married and have at least one child in the family but lost in the analysis due to other dependent variables with missing values and the 3428 actual observations used in the analysis. T-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests indicate that the means and distributions are not significant at the 1% level. However, for those who answer the bequest attitude questions but are not married and/or have no children (6060–4466 = 1594 observations), the means of bequest attitudes are lower than those of the samples used in the analysis, and the T-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests indicate that the means and distributions are significant at the 10% level.

The original coding in the questionnaire is 1, “Particularly true for me” and 5, “Does not hold at all for me.”.

Owing to data limitations, it is hard to say if the money transfer is from inheritance or inter vivos wealth transfer. For simplicity, this variable is regarded as the source of the inheritance here.

The original coding in the questionnaire is 1, “Particularly true for me” and 5, “Does not hold true at all for me.”.

A situation where a person inherits from their spouse’s parents directly is uncommon. However, if the respondent is listed in the deceased’s will as a beneficiary or they are an adopted son-in-law/daughter-in-law, the respondent has legal rights to claim inheritance from the spouse’s parents. The inheritance from parents-in-law may be shared as a gift (e.g., a down payment for a house) or transmuted into community property for both spouses. An individual who lives with and/or takes care of the parents-in-law is more likely to own the house with their spouse when the parents-in-law pass away. In those cases, they can report that they have received or expect to receive an inheritance from their parents-in-law. However, the benefits are not entirely entitled into “their own” account considering that the benefits are from their marriage to a certain person/family. For the fairness consideration, it is unfair to leave nothing to the spouse and/or children when an individual holds onto the BBFT of bequeathing.

This study uses the Stata program from Williams (2006), and autofit uses the 5% significance level by default.

The insignificant signs of INH from parents and INH from parents-in-law on bequest attitudes do not imply that an individual intends to leave nothing. An increase in an inheritance may lead to a tiny increase in bequests but is too small to be significant for bequest attitudes.

Approximately 40% of Japanese females are unemployed housewives in this study.

References

Abel, A. B. (1985). Precautionary saving and accidental bequests. American Economic Review, 75(4), 777–791.

Abel, A. B., & Warshawsky, M. (1988). Specification of the joy of giving: Insights from altruism. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(1), 145–149. https://doi.org/10.2307/1928162

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301556419

Angelini, V. (2007). The strategic bequest motive: Evidence from SHARE. In Marco Fanno Working Paper (No. 62; Marco Fanno Working Paper, Issue No.62). https://economia.unipd.it/sites/economia.unipd.it/files/20070062.pdf

Arrondel, L., & Grange, C. (2014). Bequests and family traditions: The case of nineteenth century France. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 439–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9216-7

Arrondel, L., & Masson, A. (2001). Family transfers involving three generations. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 103(3), 415–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9442.00253

Barro, R. J. (1974). Are government bonds net wealth? Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1095–1117. https://doi.org/10.1086/260266

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1063–1093. https://doi.org/10.1086/260265

Bernheim, B. D., Shleifer, A., & Summers, L. H. (1985). The strategic bequest motive. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1045–1076. https://doi.org/10.1086/298126

Bethencourt, C., & Kunze, L. (2019). Like father, like son: Inheriting and bequeathing. German Economic Review, 20(2), 194–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12143

Bhatt, V., & Ogaki, M. (2012). Tough love and intergenerational altruism. International Economic Review, 791–814. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23251497

Cherry, T. L. (2001). Mental accounting and other-regarding behavior: Evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(5), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(01)00058-7

Cherry, T. L., Frykblom, P., & Shogren, J. F. (2002). Hardnose the dictator. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1218–1221. https://doi.org/10.1257/00028280260344740

Cox, D. (1987). Motives for private income transfers. Journal of Political Economy, 95(3), 508–546. https://doi.org/10.1086/261470

Cox, D., & Rank, M. R. (1992). Inter-vivos transfers and intergenerational exchange. Review of Economics and Statistics. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109662

Cox, D., & Stark, O. (2005). Bequests, inheritances and family traditions. CRR WP, 9,. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1148982

Davies, J. B. (1981). Uncertain lifetime, consumption, and dissaving in retirement. Journal of Political Economy, 89(3), 561–577. https://doi.org/10.1086/260986

De Nardi, M. (2004). Wealth inequality and intergenerational links. Review of Economic Studies, 71(3), 743–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2004.00302.x

DeBoer, D. R., & Hoang, E. C. (2017). Inheritances and bequest planning: Evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-016-9509-0

Engelmann, D., & Fischbacher, U. (2009). Indirect reciprocity and strategic reputation building in an experimental helping game. Games and Economic Behavior, 67(2), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2008.12.006

Fahr, R., & Irlenbusch, B. (2000). Fairness as a constraint on trust in reciprocity: Earned property rights in a reciprocal exchange experiment. Economics Letters, 66(3), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(99)00236-0

Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). On the nature of fair behavior. Economic Inquiry, 41(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/ei/41.1.20

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425(6960), 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02043

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000a). Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. American Economic Review, 90(4), 980–994. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.4.980

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000b). Fairness and retaliation: The economics of reciprocity. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.14.3.159

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556151

Gale, W. G., & Scholz, J. K. (1994). Intergenerational transfers and the accumulation of wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(4), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.4.145

Horioka, C. Y. (2014). Are Americans and Indians more altruistic than the Japanese and Chinese? Evidence from a new international survey of bequest plans. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 411–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9252-y

Horioka, C. Y., Gahramanov, E., Hayat, A., & Tang, X. (2018). Why do children take care of their elderly parents? Are the Japanese any different? International Economic Review, 59(1), 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/iere.12264

Hurd, M. D. (1997). The economics of individual aging. In M. R. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics (Vol. 1, pp. 891–966). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-003X(97)80008-6

Ito, T., Kubota, K., & Ohtake, F. (2017). Jiin jizō jinja no shakai keizai-teki kiketsu: Sōsharu kyapitaru o tsūjita shotoku kōfuku-do kenkō e no eikyō [Long Term Effects of Buddhist Temples, Jizo Bodhisattvas and Shrines on a School Route: The Effects on Income, Happiness and Hea. ISER Discussion Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2945907

Japanese Law Translation. (n.d.-a). Civil Code, Article 750. Retrieved April 11, 2019, from http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?vm=&re=&id=2252&lvm=01

Japanese Law Translation. (n.d.-b). Civil Code, Article 890. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?vm=&re=&id=2252&lvm=01

Kagayama, S. (2004). Nihon no kazoku to minpō [Japanese household and civil code]. http://lawschool.jp/kagayama/material/civi_law/family/lecture2004/01_2family_civcode.html

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. American Economic Review, 728–741. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1806070

Kao, Y. E., Hong, G.-S., & Widdows, R. (1997). Bequest expectations: Evidence from the 1989 survey of consumer finances. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 18(4), 357–377. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024943421055

Kotlikoff, L. J., & Morris, J. N. (1989). How much care do the aged receive from their children? A bimodal picture of contact and assistance. In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Economics of Aging (pp. 151–176). University of Chicago Press.

Laitner, J. (2002). Wealth inequality and altruistic bequests. American Economic Review, 92(2), 270–273. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802320189384

Laitner, J., & Ohlsson, H. (2001). Bequest motives: A comparison of Sweden and the United States. Journal of Public Economics, 79(1), 205–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(00)00101-8

MacDonald, M., & Koh, S.-K. (2003). Consistent motives for inter-family transfers: Simple altruism. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 24(1), 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022435104422

Ministry of Health, L. and W. (2016). Marriage Statistics. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/vs06.html

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (n.d.). Life Tables. Retrieved September 13, 2018, from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/vs02.html

Niimi, Y., & Horioka, C. Y. (2018). The impact of intergenerational transfers on wealth inequality in Japan and the United States. World Economy, 41(8), 2042–2066. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12544

Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (2005). Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature, 437(7063), 1291. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04131

OECD. (n.d.). Ageing and Employment Policies - Statistics on average effective age of retirement. Retrieved September 19, 2018, from http://www.oecd.org/els/emp/average-effective-age-of-retirement.htm

Page, B. R. (2003). Bequest taxes, inter vivos gifts, and the bequest motive. Journal of Public Economics, 87(5–6), 1219–1229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00177-3

Perozek, M. G. (1998). A reexamination of the strategic bequest motive. Journal of Political Economy, 106(2), 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1086/250015

Rees, A. (1993). The role of fairness in wage determination. Journal of Labor Economics, 11(1, Part 1), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1086/298325

Seinen, I., & Schram, A. (2006). Social status and group norms: Indirect reciprocity in a repeated helping experiment. European Economic Review, 50(3), 581–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.10.005

Sloan, F. A., Picone, G., & Hoerger, T. J. (1997). The supply of children’s time to disabled elderly parents. Economic Inquiry, 35(2), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1997.tb01911.x

Stark, O., & Nicinska, A. (2015). How inheriting affects bequest plans. Economica, 82, 1126–1152. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12164

Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.4.3.199

Thaler, R. H. (1990). Anomalies: Saving, fungibility, and mental accounts. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(1), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.4.1.193

Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(3), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(199909)12:3%3c183::AID-BDM318%3e3.0.CO;2-F

Tomes, N. (1981). The family, inheritance, and the intergenerational transmission of inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 928–958. https://doi.org/10.1086/261014

Wilhelm, M. O. (1996). Bequest behavior and the effect of heirs’ earnings: Testing the altruistic model of bequests. American Economic Review, 874–892. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118309

Williams, R. (2006). Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. Stata Journal, 6(1), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0600600104

Williams, R. (2016). Understanding and interpreting generalized ordered logit models. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 40(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.2015.1112384

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press.

Yaari, M. E. (1965). Uncertain lifetime, life insurance, and the theory of the consumer. Review of Economic Studies, 32(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022435104422

Yamada, K. (2006). Intra-family transfers in Japan: Intergenerational co-residence, distance, and contact. Applied Economics, 38(16), 1839–1861. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600825746

Funding

This work was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up) Grant Number 20K22098, a grant from Keio Economic Society, and a grant from the Doctorate Student Grant-in-Aid Program at Keio University. I am grateful to Masao Ogaki, Colin McKenzie, and Charles Yuji Horioka. This research utilizes the micro-data from the Preference Parameters Study of Osaka University’s 21st Century COE Program “Behavioral Macrodynamics Based on Surveys and Experiments” and its Global COE project “Human Behavior and Socioeconomic Dynamics.” I acknowledge the program/project’s contributors: Yoshiro Tsutsui, Fumio Ohtake, and Shinsuke Ikeda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix A

In the case of pure altruism, an individual chooses the amount of the bequest to the child and spouse to maximize the utility function, given as

Then,

\(\frac{{\partial^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c}^{2} }}\frac{{\partial^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s}^{2} }} - \left( {\frac{{\partial^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} \partial b_{s} }}} \right)^{2} = \frac{{\alpha_{c} \alpha_{s} }}{{\left( {b_{c} + y_{c} } \right)^{2} \left( {b_{s} + y_{s} } \right)^{2} }} + \frac{{\alpha_{c} \left( {1 - \alpha_{c} - \alpha_{s} } \right)}}{{\left( {b_{c} + y_{c} } \right)^{2} \left( { - b_{c} - b_{s} + h_{p} + h_{sp} + y_{i} } \right)^{2} }} + \frac{{\alpha_{s} \left( {1 - \alpha_{c} - \alpha_{s} } \right)}}{{\left( {b_{s} + y_{s} } \right)^{2} \left( { - b_{c} - b_{s} + h_{p} + h_{sp} + y_{i} } \right)^{2} }} > 0\) Because \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}U}{\partial {{b}_{c}}^{2}}<0\) and \( \frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s} ^{2} }} < 0,\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} ^{2} }}\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s} ^{2} }} - \left( {\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} \partial b_{s} }}} \right)^{2} > 0 \) for all \({b}_{c}\) and \({b}_{s}\); then, the utility \(U\left({b}_{c},{b}_{s}\right)\) will reach its maximum when

Appendix B

In the case of the pure joy of giving, an individual chooses the amount of the bequest to the child and spouse to maximize the utility function, given as

Then,

Because \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}U}{\partial {{b}_{c}}^{2}}<0\) and \( \frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s} ^{2} }} < 0,\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} ^{2} }}\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s} ^{2} }} - \left( {\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} \partial b_{s} }}} \right)^{2} > 0 \) for all \({b}_{c}\) and \({b}_{s}\); then, the utility \(U\left({b}_{c},{b}_{s}\right)\) will reach its maximum when

Appendix C

In the case of pure BBFT, an individual chooses the amount of the bequest to the child and spouse to maximize the utility function, given as

Then,

Because \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}U}{\partial {{b}_{c}}^{2}}<0\) and \( \frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s} ^{2} }} < 0,\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} ^{2} }}\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{s} ^{2} }} - \left( {\frac{{\partial ^{2} U}}{{\partial b_{c} \partial b_{s} }}} \right)^{2} > 0 \) for all \({b}_{c}\) and \({b}_{s}\); then, the utility \(U\left({b}_{c},{b}_{s}\right)\) will reach its maximum when

There are other propositions in the pure BBFT model, where \({\beta }_{c},{\beta }_{s}>0\), \(0<{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\), \(\left|\theta \right|+\left|{\gamma }_{c}\right|\ne 0\),\(0\le \theta ,{\gamma }_{c}\le 1\), and \({\gamma }_{c}+{\gamma }_{s}\le 1\):

Proposition 3. In a family tradition stronger toward the child, ceteris paribus, the bequest to the child increases, while the bequest to the spouse decreases. In a family tradition stronger toward the spouse, ceteris paribus, the bequest to the child decreases, while the bequest to the spouse increases:

Proposition 4. When there is greater weight on the child in the respondent’s bloodline family, ceteris paribus, the bequest to the child increases, while the bequest to the spouse decreases:

Proposition 5. When there is greater weight on the child in the spouse’s bloodline family, ceteris paribus, the bequest to the child increases, while that to the spouse decreases. When there is greater weight on the spouse in the spouse’s bloodline family, ceteris paribus, the bequest to the child decreases, while that to the spouse increases:

Appendix D Full Results for Table 5

See Table 6.

Appendix E

Suppose \(x=\frac{{\beta }_{cf}}{{\beta }_{cm}}\) and \(y=\frac{{\beta }_{sf}}{{\beta }_{sm}}\); then, \(x{\beta }_{cm}={\beta }_{cf}\) and \(y{\beta }_{sm}={\beta }_{sf}\),

When \(y-1<0\),

Because \(0<\frac{{\beta }_{sm}}{1+{\beta }_{sm}}<\frac{1+{\beta }_{cm}}{{\beta }_{cm}}\), then, \((x-1)/(y-1)\) does not exist. In this case, \(y-1<0\) is rejected.

When \(y-1>0\),

Because \(0<\frac{{\beta }_{sm}}{1+{\beta }_{sm}}<\frac{1+{\beta }_{cm}}{{\beta }_{cm}}\) and \(y-1>0\); then, \(x-1>0\). In this case, \(x>1\iff {\beta }_{cf}>{\beta }_{cm}\) and \(y>1\iff {\beta }_{sf}>{\beta }_{sm}\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M. Does the Source of Inheritance Matter in Bequest Attitudes? Evidence from Japan. J Fam Econ Iss 43, 867–887 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09803-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09803-2